Abstract

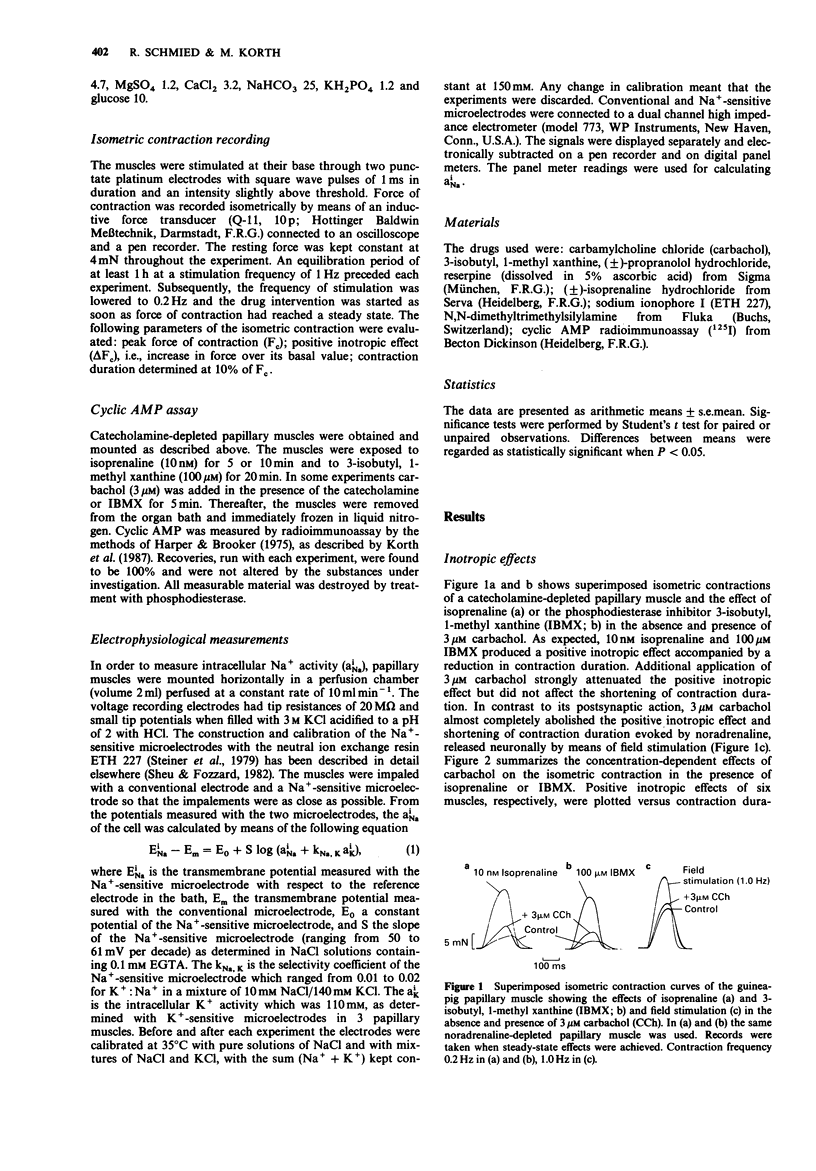

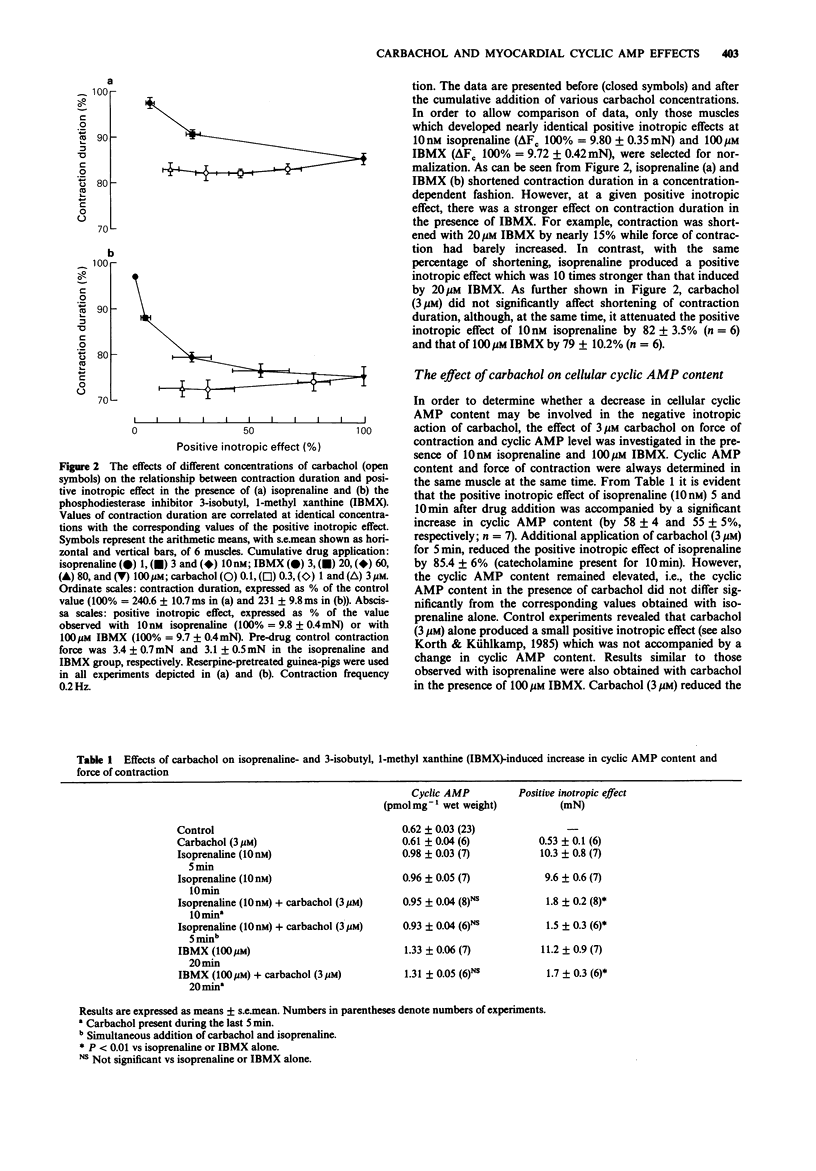

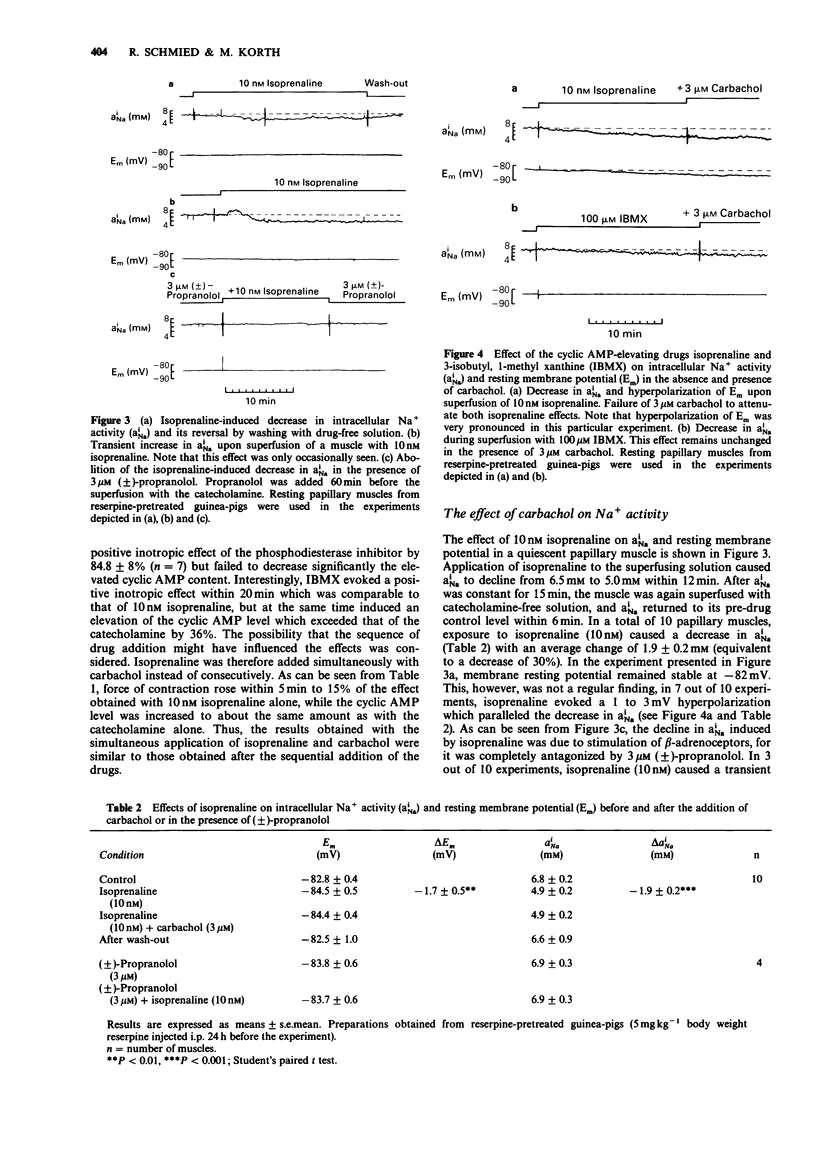

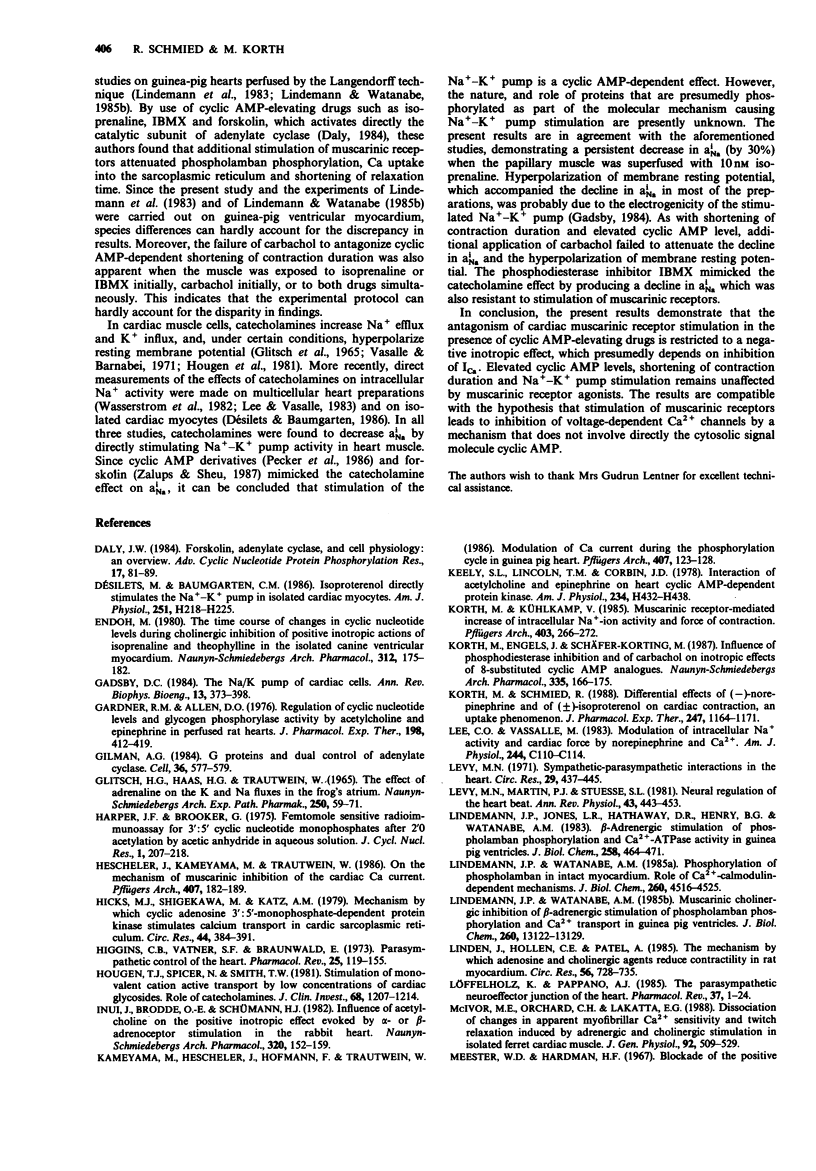

1. The effect of carbachol on force of contraction, contraction duration, intracellular Na+ activity and cyclic AMP content was studied in papillary muscles of the guinea-pig exposed to isoprenaline or the phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl, 1-methyl xanthine (IBMX). The preparations were obtained from reserpine-pretreated animals and were electrically driven at a frequency of 0.2 Hz. 2. Isoprenaline (10 nM) and IBMX (100 microM) produced comparable positive inotropic effects of 9.8 and 9.7 mN, respectively. Carbachol (3 microM) attenuated the inotropic effects by 82% (isoprenaline) and by 79% (IBMX). The shortening of contraction duration which accompanied the positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline (by 14.9%) and of IBMX (by 22.4%) was not significantly affected by 3 microM carbachol. 3. The positive inotropic effect of 10 nM isoprenaline and of 100 microM IBMX was accompanied by an increase in cellular cyclic AMP content of 58 and 114%, respectively. Carbachol (3 microM) failed to reduce significantly the elevated cyclic AMP content of muscles exposed to either isoprenaline or IBMX. 4. In the quiescent papillary muscle, isoprenaline (10 nM) and IBMX (100 microM) reduced the intracellular Na+ activity by 28 and 17%, respectively. This decline was not influenced by the additional application of 3 microM carbachol. 5. The results demonstrate that muscarinic antagonism in guinea-pig ventricular myocardium exposed to cyclic AMP-elevating drugs is restricted to force of contraction. The underlying mechanism does not apparently involve the cytosolic signal molecule cyclic AMP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Daly J. W. Forskolin, adenylate cyclase, and cell physiology: an overview. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1984;17:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Désilets M., Baumgarten C. M. Isoproterenol directly stimulates the Na+-K+ pump in isolated cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1986 Jul;251(1 Pt 2):H218–H225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.1.H218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M. The time course of changes in cyclic nucleotide levels during cholinergic inhibition of positive inotropic actions of isoprenaline and theophylline in the isolated canine ventricular myocardium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1980 Jun;312(2):175–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00569727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLITSCH H. G., HAAS H. G., TRAUTWEIN W. THE EFFECT OF ADRENALINE ON THE K AND NA FLUXES IN THE FROG'S ATRIUM. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol. 1965 Feb 2;250:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00246883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D. C. The Na/K pump of cardiac cells. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1984;13:373–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.13.060184.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R. M., Allen D. O. Regulation of cyclic nucleotide levels and glycogen phosphorylase activity by acetylcholine and epinephrine in perfused rat hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976 Aug;198(2):412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman A. G. G proteins and dual control of adenylate cyclase. Cell. 1984 Mar;36(3):577–579. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. F., Brooker G. Femtomole sensitive radioimmunoassay for cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP after 2'0 acetylation by acetic anhydride in aqueous solution. J Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1975;1(4):207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hescheler J., Kameyama M., Trautwein W. On the mechanism of muscarinic inhibition of the cardiac Ca current. Pflugers Arch. 1986 Aug;407(2):182–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00580674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks M. J., Shigekawa M., Katz A. M. Mechanism by which cyclic adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase stimulates calcium transport in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Circ Res. 1979 Mar;44(3):384–391. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C. B., Vatner S. F., Braunwald E. Parasympathetic control of the heart. Pharmacol Rev. 1973 Mar;25(1):119–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougen T. J., Spicer N., Smith T. W. Stimulation of monovalent cation active transport by low concentrations of cardiac glycosides. Role of catecholamines. J Clin Invest. 1981 Nov;68(5):1207–1214. doi: 10.1172/JCI110366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui J., Brodde O. E., Schümann H. J. Influence of acetylcholine on the positive inotropic effect evoked by alpha- or beta-adrenoceptor stimulation in the rabbit heart. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1982 Aug;320(2):152–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00506315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M., Hescheler J., Hofmann F., Trautwein W. Modulation of Ca current during the phosphorylation cycle in the guinea pig heart. Pflugers Arch. 1986 Aug;407(2):123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00580662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely S. L., Jr, Lincoln T. M., Corbin J. D. Interaction of acetylcholine and epinephrine on heart cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1978 Apr;234(4):H432–H438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.4.H432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth M., Engels J., Schäfer-Korting M. Influence of phosphodiesterase inhibition and of carbachol on inotropic effects of 8-substituted cyclic AMP analogues. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987 Feb;335(2):166–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00177719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth M., Kühlkamp V. Muscarinic receptor-mediated increase of intracellular Na+-ion activity and force of contraction. Pflugers Arch. 1985 Mar;403(3):266–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00583598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth M., Schmied R. Differential effects of (-)-norepinephrine and of (+/-)-isoproterenol on cardiac contraction, an uptake phenomenon. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Dec;247(3):1164–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. N., Martin P. J., Stuesse S. L. Neural regulation of the heart beat. Annu Rev Physiol. 1981;43:443–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.43.030181.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. N. Sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions in the heart. Circ Res. 1971 Nov;29(5):437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.29.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann J. P., Watanabe A. M. Muscarinic cholinergic inhibition of beta-adrenergic stimulation of phospholamban phosphorylation and Ca2+ transport in guinea pig ventricles. J Biol Chem. 1985 Oct 25;260(24):13122–13129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann J. P., Watanabe A. M. Phosphorylation of phospholamban in intact myocardium. Role of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1985 Apr 10;260(7):4516–4525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J., Hollen C. E., Patel A. The mechanism by which adenosine and cholinergic agents reduce contractility in rat myocardium. Correlation with cyclic adenosine monophosphate and receptor densities. Circ Res. 1985 May;56(5):728–735. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löffelholz K., Pappano A. J. The parasympathetic neuroeffector junction of the heart. Pharmacol Rev. 1985 Mar;37(1):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIvor M. E., Orchard C. H., Lakatta E. G. Dissociation of changes in apparent myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity and twitch relaxation induced by adrenergic and cholinergic stimulation in isolated ferret cardiac muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1988 Oct;92(4):509–529. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meester W. D., Hardman H. F. Blockade of the positive inotropic actions of epinephrine and theophylline by acetylcholine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1967 Nov;158(2):241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecker M. S., Im W. B., Sonn J. K., Lee C. O. Effect of norepinephrine and cyclic AMP on intracellular sodium ion activity and contractile force in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1986 Oct;59(4):390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter M. Die Wertbestimmung inotrop wirkender Arzneimittel am isolierten Papillarmuskel. Arzneimittelforschung. 1967 Oct;17(10):1249–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodbell M. The role of hormone receptors and GTP-regulatory proteins in membrane transduction. Nature. 1980 Mar 6;284(5751):17–22. doi: 10.1038/284017a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu S. S., Fozzard H. A. Transmembrane Na+ and Ca2+ electrochemical gradients in cardiac muscle and their relationship to force development. J Gen Physiol. 1982 Sep;80(3):325–351. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M., Kirchberger M. A., Katz A. M. Phosphorylation of a 22,000-dalton component of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1975 Apr 10;250(7):2640–2647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalle M., Barnabei O. Norepinephrine and potassium fluxes in cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1971;322(4):287–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00587747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstrom J. A., Schwartz D. J., Fozzard H. A. Catecholamine effects on intracellular sodium activity and tension in dog heart. Am J Physiol. 1982 Nov;243(5):H670–H675. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.5.H670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A. M., Besch H. R., Jr Interaction between cyclic adenosine monophosphate and cyclic gunaosine monophosphate in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1975 Sep;37(3):309–317. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups R. K., Sheu S. S. Effects of forskolin on intracellular sodium activity in resting and stimulated cardiac Purkinje fibers from sheep. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987 Sep;19(9):887–896. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80617-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]