Abstract

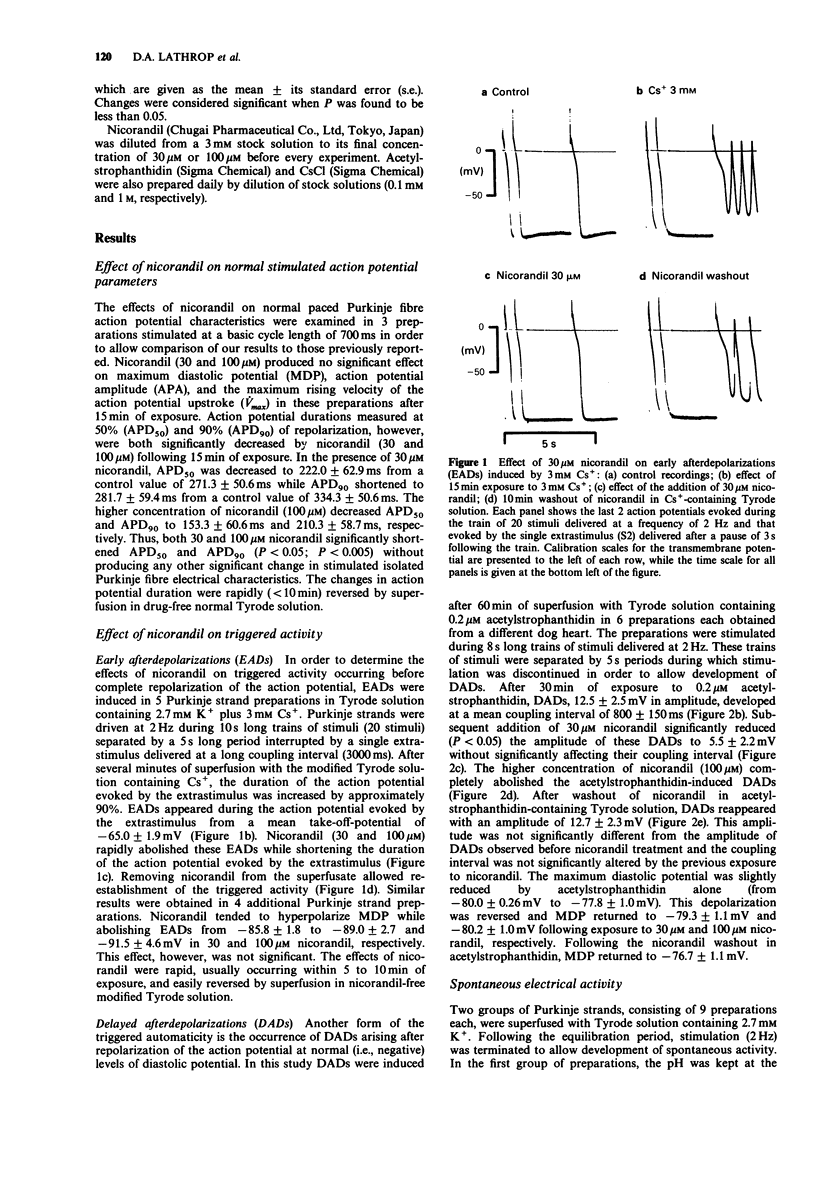

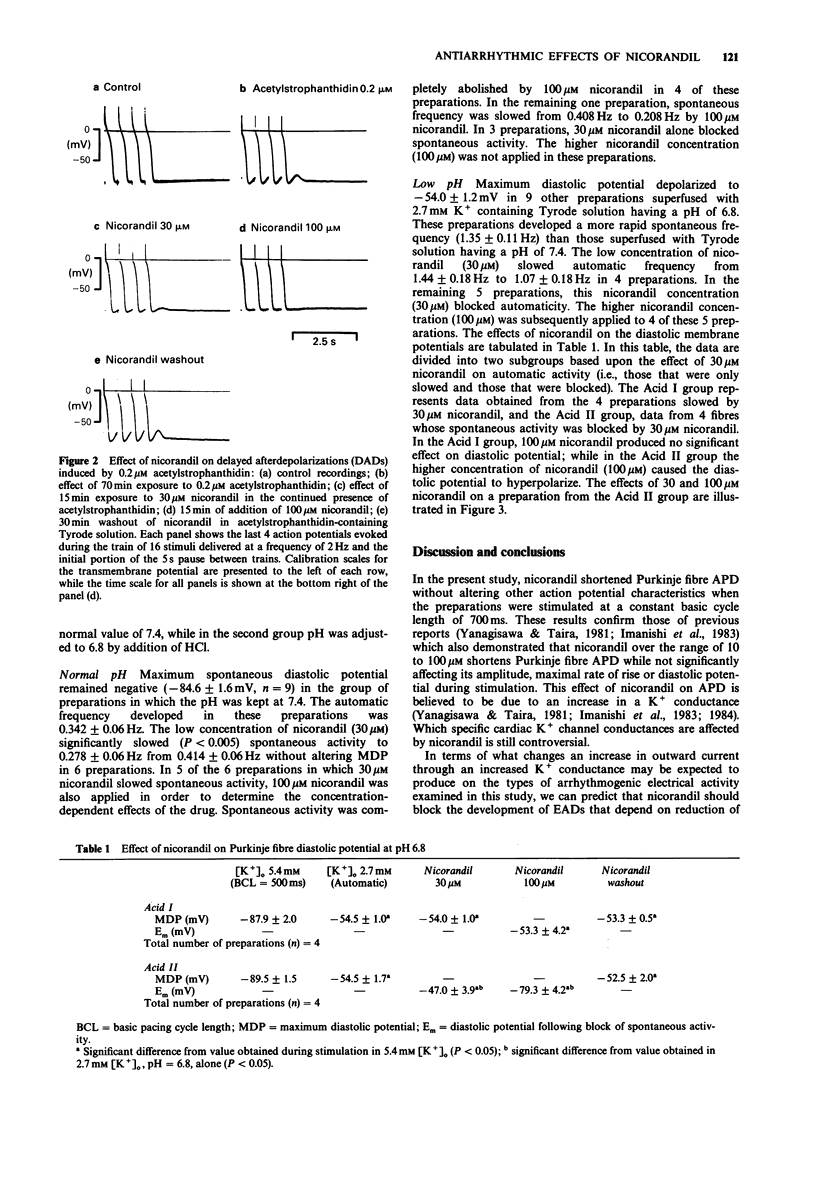

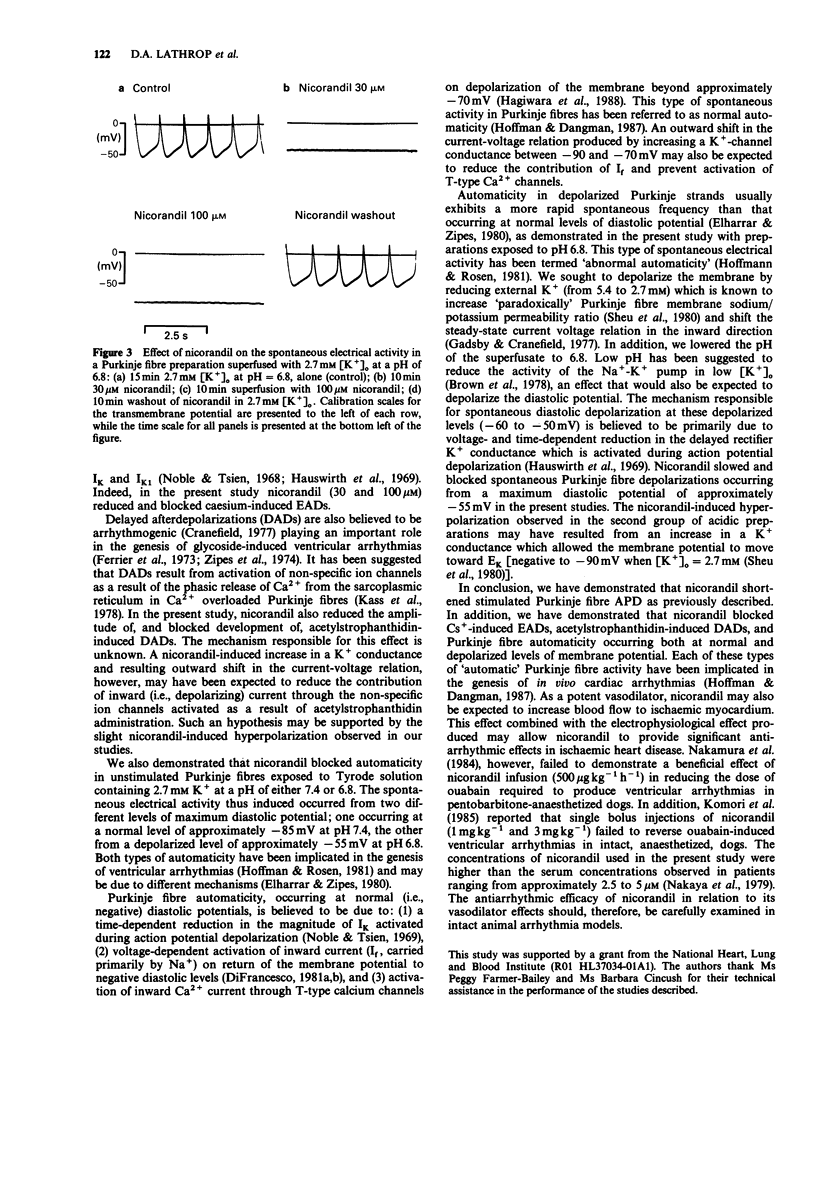

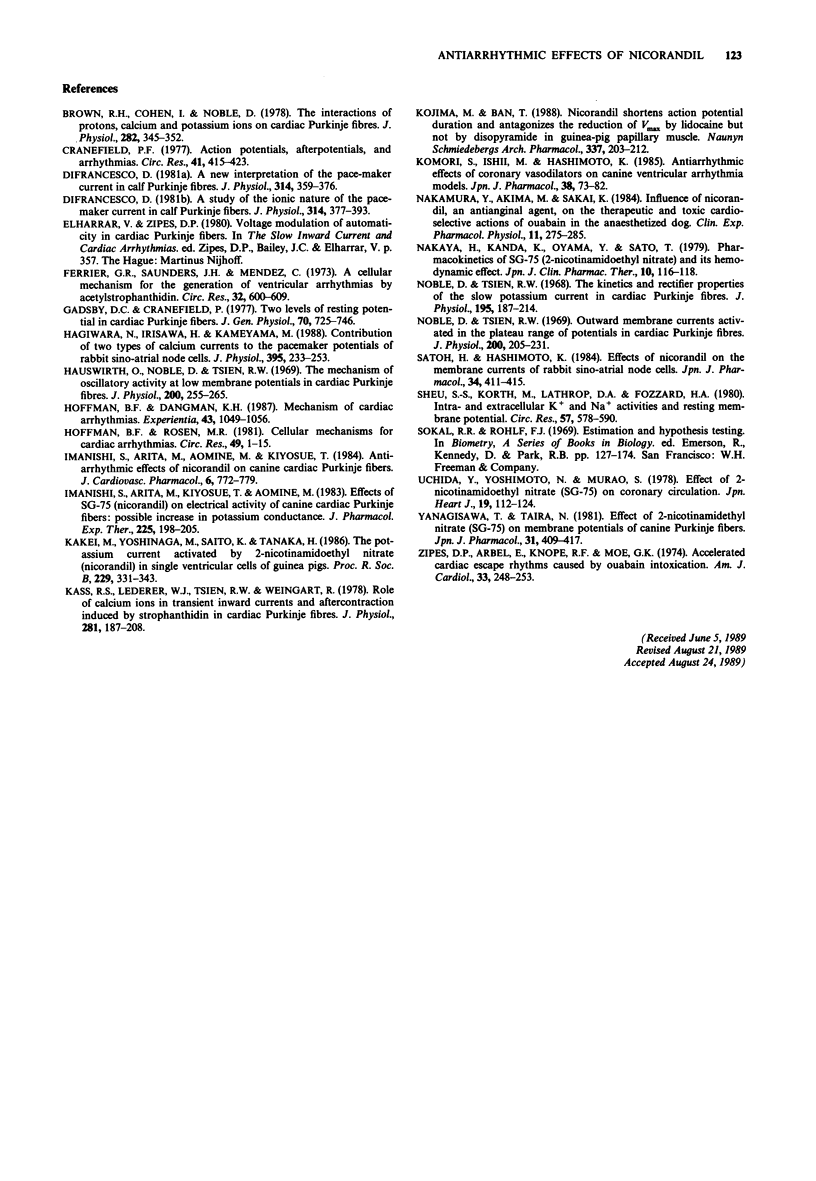

1. The effects of nicorandil (30 microM and 100 microM) on two models of triggered activity [early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs)] and on spontaneous automaticity occurring from both normal and depolarized levels of membrane potential were examined in isolated cardiac Purkinje fibres of the dog. Standard intracellular microelectrode techniques were used. 2. Nicorandil (30 microM) abolished EADs provoked by superfusion with Tyrode solution containing 2.7 mM K+ and 3 mM Cs. 3. DADs were induced by 0.2 microM acetylstrophanthidin in Tyrode solution containing 5.4 mM K+. Nicorandil (30 microM) significantly reduced the amplitude of these DADs from 12.5 +/- 2.5 mV to 5.5 +/- 0.2 mV (P less than 0.02, n = 6), while DADs were fully abolished by 100 microM nicorandil. 4. In unstimulated Purkinje strands, superfused with 2.7 mM K+ containing Tyrode solution having a pH of either 7.4 or 6.8, spontaneous depolarizations developed with a mean maximum diastolic potential (MDP) of -84.6 +/- 1.6 mV (n = 9) or -54.0 +/- 1.2 mV (n = 9), respectively. Nicorandil significantly reduced the frequency of this automatic activity and caused its cessation, at either level of MDP. Nicorandil, however, produced significant hyperpolarization only when automaticity occurred from the depolarized level of potential. 5. These results suggest that nicorandil may exert significant antiarrhythmic actions in vivo by abolishing both spontaneous and triggered electrical activity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brown R. H., Jr, Cohen I., Noble D. The interactions of protons, calcium and potassium ions on cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1978 Sep;282:345–352. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranefield P. F. Action potentials, afterpotentials, and arrhythmias. Circ Res. 1977 Oct;41(4):415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. A new interpretation of the pace-maker current in calf Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1981 May;314:359–376. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. A study of the ionic nature of the pace-maker current in calf Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1981 May;314:377–393. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier G. R., Saunders J. H., Mendez C. A cellular mechanism for the generation of ventricular arrhythmias by acetylstrophanthidin. Circ Res. 1973 May;32(5):600–609. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.5.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D. C., Cranefield P. F. Two levels of resting potential in cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1977 Dec;70(6):725–746. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.6.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N., Irisawa H., Kameyama M. Contribution of two types of calcium currents to the pacemaker potentials of rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1988 Jan;395:233–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauswirth O., Noble D., Tsien R. W. The mechanism of oscillatory activity at low membrane potentials in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1969 Jan;200(1):255–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B. F., Dangman K. H. Mechanisms for cardiac arrhythmias. Experientia. 1987 Oct 15;43(10):1049–1056. doi: 10.1007/BF01956038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B. F., Rosen M. R. Cellular mechanisms for cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res. 1981 Jul;49(1):1–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi S., Arita M., Aomine M., Kiyosue T. Antiarrhythmic effects of nicorandil on canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1984 Sep-Oct;6(5):772–779. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198409000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi S., Arita M., Kiyosue T., Aomine M. Effects of SG-75 (nicorandil) on electrical activity of canine cardiac Purkinje fibers: possible increase in potassium conductance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983 Apr;225(1):198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakei M., Yoshinaga M., Saito K., Tanaka H. The potassium current activated by 2-nicotinamidoethyl nitrate (nicorandil) in single ventricular cells of guinea pigs. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986 Dec 22;229(1256):331–343. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1986.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass R. S., Lederer W. J., Tsien R. W., Weingart R. Role of calcium ions in transient inward currents and aftercontractions induced by strophanthidin in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1978 Aug;281:187–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M., Ban T. Nicorandil shortens action potential duration and antagonises the reduction of Vmax by lidocaine but not by disopyramide in guinea-pig papillary muscles. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988 Feb;337(2):203–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00169249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori S., Ishii M., Hashimoto K. Antiarrhythmic effects of coronary vasodilators on canine ventricular arrhythmia models. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1985 May;38(1):73–82. doi: 10.1254/jjp.38.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Akima M., Sakai K. Influence of nicorandil, an antianginal agent, on the therapeutic and toxic cardiovascular actions of ouabain in the anaesthetized dog. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1984 May-Jun;11(3):275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1984.tb00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D., Tsien R. W. Outward membrane currents activated in the plateau range of potentials in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1969 Jan;200(1):205–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D., Tsien R. W. The kinetics and rectifier properties of the slow potassium current in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1968 Mar;195(1):185–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H., Hashimoto K. Effects of nicorandil on the membrane currents of rabbit sino-atrial node cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1984 Apr;34(4):411–415. doi: 10.1254/jjp.34.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu S. S., Lederer W. J. Lidocaine's negative inotropic and antiarrhythmic actions. Dependence on shortening of action potential duration and reduction of intracellular sodium activity. Circ Res. 1985 Oct;57(4):578–590. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y., Yoshimoto N., Murao S. Effect of 2-nicotinamidethyl nitrate (SG 75) on coronary circulation. Jpn Heart J. 1978 Jan;19(1):112–124. doi: 10.1536/ihj.19.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa T., Taira N. Effect of 2-nicotinamidethyl nitrate (SG-75) on membrane potentials of canine Purkinje fibers. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1981 Jun;31(3):409–417. doi: 10.1254/jjp.31.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P., Arbel E., Knope R. F., Moe G. K. Accelerated cardiac escape rhythms caused by ouabain intoxication. Am J Cardiol. 1974 Feb;33(2):248–253. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]