Although harmful side effects have not been reported in humans associated with the clinical application of continuous wave (CW) ultrasound (typical of therapeutic applications) or pulsed ultrasound (typical of diagnostic applications), bioeffects have been reported in non-human mammalian species with both waveforms. Bioeffects have been reported in organ systems that have tissues associated with well-defined gas bodies, such as lung and intestine, and in tissues not associated with well-defined gas bodies, such as nervous tissue, liver, kidney, and reproductive tissues. Lesions in tissues with well-defined gas bodies include hemorrhage in lung and intestine; lesions in tissues without well-defined gas bodies include cell and tissue destruction and necrosis with tissue-specific hemorrhage in nervous tissue, liver, kidney, and reproductive tissues.

Studies suggest that there are unique differences in the responses of tissues to CW and pulsed ultrasound among animal species and within a species based on age or stage of development. Data from reference materials covering the anatomy and histology of animal tissues indicate that important structural differences exist among species and within a species based on age or stage of development. These structural differences and how they influence the responses of tissues and organs to ultrasound appear to be focused on the serosal surfaces (protective coverings) of these organs. Such surfaces include, but are not limited to, the visceral pleura of the lung and the visceral peritoneum of all abdominal organs. The thickness and composition (e.g., structural fiber type, collagen, or elastic fibers) of these surfaces and their contiguous internal structural units, such as septa and trabecula, also appear to be important in determining the susceptibility of a tissue or organ to ultrasound-induced damage.

Although data exist that support the hypothesis that there are species differences in susceptibility to CW ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage, data from studies using pulsed ultrasound are less abundant but suggest that species differences in susceptibility to pulsed ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage may also possibly exist. Species differences in susceptibility to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage appear inversely related to the thickness of the visceral pleura of the lung. Although pulsed ultrasound can induce hemorrhage in the intestine of mice, there are no data from intestinal studies currently available suggesting there are species differences in susceptibility to pulsed ultrasound. There exists, for the intestine, information similar to that reported in the lung, which documents innate tissue and organ differences among mammalian species that could influence susceptibility to pulsed ultrasound.

The analysis, interpretation, and speculation regarding bioeffects and tissue properties documented in this section and the conclusions presented likely will mature and evolve as new information becomes available through additional in vivo bioeffects research.

This section is a compilation of information pertinent to developing an initial understanding of selected biological properties of tissues that may be associated with susceptibility to injury caused by ultrasound used during therapy, usually CW or diagnostic examination (pulsed). Susceptibility is defined as “a characteristic rendering an individual liable to acquire a disease if exposed to a causative agent.” In this section, a “characteristic” is one or more innate structural properties of tissues or organs, “disease” is hemorrhage or other tissue damage, and the “causative agent” is CW or pulsed ultrasound.

In preparing this section, it became clear it would be difficult to develop an inclusive section documenting all possible structural or functional attributes present within tissues that could contribute to a potentially harmful bioeffect. At our present level of understanding, any consideration of molecular differences between cells or subcellular organelles and how these differences might relate to biological properties of tissues and, therefore, susceptibility to injury caused by ultrasound, was premature. In addition, discussion and analysis of properties related to some tissues and organ systems, such as the lung and intestine, were significantly easier to accomplish, based on the availability of biomedical data, than those associated with nervous tissue, liver, kidney, and reproductive tissues. As a result, this section and the discussion of tissue properties and how they may interact with ultrasound through one or more mechanisms was based on the published literature covering ultrasound bioeffects and histologic anatomy. This section was developed using the terminology and definitions documented in Section 2, the characterization of ultrasound-induced lesions detailed in Section 4, and the themes expressed in the remaining sections.

The conclusions developed for this section represent an analysis and extrapolation of currently available experimental data and established anatomic and morphologic tissue properties.

3.1 Tissues with Well-Defined Gas Bodies

3.1.1 Lung

Morphologic studies describing the macroscopic and microscopic lesions induced in lung tissue by continuous wave (CW) ultrasound exposure at a frequency of 30 kHz and by pulsed ultrasound exposure at megahertz frequencies have been reported in neonatal, juvenile, and adult mice (Child et al, 1990; Penney et al, 1993; Raeman et al, 1993; Frizzell et al, 1994; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995; Raeman et al, 1996; O’Brien and Zachary, 1997; Dalecki et al, 1997a), rabbits (Zachary and O’Brien, 1995), neonatal pigs (Baggs et al, 1996), young pigs (Dalecki et al, 1997c), and infant to adult monkeys (Tarantal and Canfield, 1994). Studies using juvenile to adult pigs demonstrated that pulmonary hemorrhage could not be induced in these animals by exposure to pulsed ultrasound (O’Brien and Zachary, 1997). The exact age associated with any grouping listed above, such as neonatal, juvenile, or adult, is reported in Section 4.

In affected species, lesions induced by CW and pulsed ultrasound were similar and characterized by alveolar hemorrhage and congestion in alveolar capillaries. Lesions in mice (Penney et al, 1993; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995) and rabbits (Zachary and O’Brien, 1995) and, generally, in monkeys (Tarantal and Canfield, 1994) were contiguous with the visceral pleural surface of the lung (see Fig. 3-1 and discussion later in this section) and thus appeared to arise at this site and spread into contiguous lung parenchyma (Zachary and O’Brien, 1995). Studies using CW and pulsed ultrasound have demonstrated that the severity of the lesion is not necessarily closely related to the duration of exposure; a severe lesion can occur following an exposure time of < 5 s (Vladimirtseva and Manzhos, 1986; Raeman et al, 1996; Personal observation, J.F. Zachary). Histologic evaluations of affected lung tissue from mice, rabbits, and pigs following exposure to CW or pulsed ultrasound indicate that pulmonary hemorrhage does not arise from damage to arterioles or venules (macrovasculature), respiratory bronchioles, or distal airways (air conduction system) (Penney et al, 1993; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995). Therefore, these structures likely play no role in determining differences in susceptibility to ultrasound-induced bioeffects among species or within a species based on age. Evaluation of data from both light and electron microscopic studies suggests that lung lesions induced by both CW and pulsed ultrasound originate at capillaries (microvasculature) located within visceral pleura and contiguous alveolar septa (Penney et al, 1993; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995).

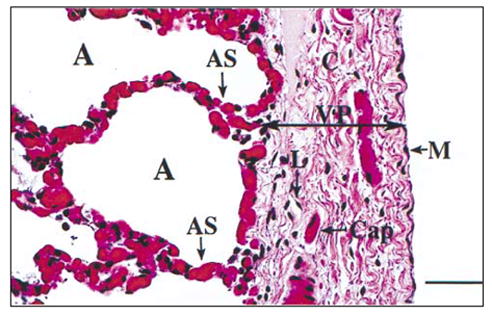

Figure 3-1.

Visceral pleura (arrows, VP), adult pig lung. The surface of the pleura is covered by a uniform layer of mesothelium (M), which is similar among all species. The pleura consists of pink collagen fibers (C) and contains capillaries (Cap) and lymphatic vessels (L). The visceral pleura is contiguous with alveoli (A) and alveolar septa (AS), which contain abundant capillaries and some collagen fibers. H&E stain, bar = 40 μm.

Extensive studies have shown that unique relationships exist between lung properties and the animal’s body weight as demonstrated in Figure 3-2 (West, 1990; Mercer and Crapo, 1992; Pinkerton, Gehr, and Crapo, 1992; Jones and Longworth, 1992). Such studies document allometric relationships, which are defined in Gould Medical Dictionary, (Jones et al, 1972) as “the quantitative relation between the size of a part and the whole, or of another part, in a series of related organisms that differ in size.” Lung properties include, as examples, such measurable units as alveolar diameter and alveolar surface area. Such allometric relationships provide important comparisons related to lung properties among species, such as alveolar diameter, lung volume, and lung compliance or resistance properties (Mercer and Crapo, 1992; Watson, 1992; Pinkerton, Gehr, and Crapo, 1992). The relative values for these lung properties (physiologic variables) for different species are compared with those of the adult mouse in Table 3-1. From a functional viewpoint, lung properties, such as total lung volume, alveolar surface area, mean alveolar diameter, capillary surface area, capillary volume, lung compliance, and pleural blood supply, are directly or indirectly related to the thickness and composition of the visceral pleura and alveolar septa. These properties may play important roles in determining the susceptibility of the lung to ultrasound-induced damage.

Figure 3-2.

Contrived example of relative allometric relationships among species. The species relationships shown in this figure provide an example of how species relate to each other in comparisons of body weight and lung properties. Such relationships suggest there are unique species differences in these lung properties that may be determined by innate anatomical and histological differences among species. Lung properties include units of measurement, such as alveolar diameter, alveolar surface area, and alveolar volume. Allometric relationships are defined as the “quantitative relation between the size of a part and the whole, or of another part, in a series of related organisms that differ in size.”

Table 3-1.

Lung Properties for Various Adult Mammalian Species Compared with the Adult Mouse

| Lung Property | Adult Mouse | Adult Rat | Adult Rabbit | Adult Cat | Adult Monkey | Adult Dog | Adult Pig | Adult Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lung volumea,g,h | 1 | ≈11 | ≈100 | ≈230 | ≈230 | ≈1,700 | ≈5,000 | ≈6,500 |

| Alveolar surface areaa,h | 1 | ≈6 | ≈65 | ≈80 | ≈130 | ≈1,800 | ≈1,500 | ≈1,500 |

| Mean alveolar diametera,b,c | 1 | ≈1 | ≈2 | ≈2.5 | ≈2.5 | ≈2 | ≈2.3 | ≈5 |

| Capillary surface areah | 1 | ≈7.2 | ≈85 | ≈76 | ≈218 | ≈1,500 | NA | ≈2,300 |

| Capillary volumeh | 1 | ≈6.6 | ≈95 | ≈67 | ≈213 | ≈1,700 | NA | ≈2,800 |

| Lung compliancea,d,e,f | 1 | ≈11 | ≈175 | ≈325 | ≈750 | ≈3,100 | ≈750 | ≈4,000 |

Weibel (1971);

Tenney and Remmers (1963);

Crosfill and Widdicombe (1961);

Hildebrandt and Young (1966);

Ganong (1967);

Watson (1992);

Sahebjami (1992);

Pinkerton et al (1992).

NA, data not available.

In addition to these lung properties that can be used to group animal species (Table 3-1), the critical structural features that can be used to separate species into distinct groups (Table 3-2) are (1) pleural thickness (thin versus thick), (2) pleural blood supply (pulmonary artery versus bronchial artery), (3) quantity of septal or interlobular connective tissue (scant versus abundant), and (4) relative thickness of the chest wall (thin or thick [relative amounts of skin, muscle, fat, connective tissue]). While all common mammalian species have parietal and visceral pleural surfaces, the thickness, vascularity, and organization of the mesothelium, submesothelial connective tissue, and vascular system forming, in particular, the visceral pleura vary among mammalian species (Tyler and Julian, 1992). The extent and distribution of secondary septation within the lung as well as the quantity and distribution of connective tissue and elastic fibers also varies among these species (Tyler and Julian, 1992). Details on these differences and groupings, based on visceral pleura thickness, are listed in Table 3-2. On the basis of these comparisons for mature animals (Tyler and Julian, 1992), mice, rats, rabbits, cats, dogs, and monkeys can be classified in the thin group (≈10–25 μm); whereas sheep, pigs, humans, cattle, horses, and other large mammals can be categorized in the thick group (≈100–150 μm or greater).

Table 3-2.

Comparative Lung Morphology

| Lung Property | Mouse/Rat/Rabbit | Cat/Dog | Monkey | Pig | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral pleura thicknessa | Thin | Thin | Thin | Thick | Thick |

| Visceral pleura blood supplya | Pulmonary artery | Pulmonary artery | Pulmonary artery | Bronchial artery | Bronchial artery |

| Interlobular and segmental connective tissuea | Little, if any | Little, if any | Little | Extensive, interlobular, surrounds many lobules completely | Extensive, interlobular, surrounds many lobules completely |

| Visceral pleura lymphaticsa | Very few | Few | Few | Extensive | Extensive |

| Nonrespiratory bronchiole (nonalveolarized)a | Several generations | Fewer generations | Fewer generations | Several generations | Several generations |

| Respiratory bronchiole (alveolarized)a,b | Absent or single short generation | Several generations | Several generations | Absent or single short generation | Several generations |

| Terminal respiratory bronchiolea | Ends in alveolar ducts or very short respiratory bronchioles | Ends in respiratory bronchioles | Ends in respiratory bronchioles | Ends in alveolar ducts or very short bronchioles | Ends in respiratory bronchioles |

| Acinus transition zonea,b | Abrupt | Not abrupt | Not abrupt | NA | Not abrupt |

Tyler and Julian (1992);

Pinkerton et al (1992).

NA indicates the information could not be found.

Acinus transition zone = the area of transition between the tracheobronchial tree and the gas-exchange area.

In addition, the supply of arterial blood to the visceral pleura and its systemic pressure vary among species (Table 3-2) and this variation is related to the thinness or thickness of the visceral pleura (Kay, 1992). Species in the thin visceral pleura group have a pleural blood supply derived from the pulmonary artery—a lower pressure/higher volume arterial supply; species in the thick visceral pleura group have a pleural blood supply derived from the bronchial artery—a higher pressure/lower volume arterial supply. The significance of the differences in blood supply to the visceral pleura based on thickness and its relationship to ultrasound-induced bio-effects is unknown at this time. These observations concerning tissue properties also are perhaps of great importance when considering the potential for gas body activity and the resultant tissue damage it may cause, as well as noncavitation-related causes of tissue damage (Flynn, 1964; Nyborg, 1965; Flynn, 1982; Frizzell et al, 1983; Atchley et al, 1988; Lee and Frizzell, 1988; Holland and Apfel, 1989; Roy et al, 1990; Child et al, 1990; Carstensen et al, 1990a; Hartman et al, 1990; Apfel and Holland, 1991; Madanshetty et al, 1991; Holland et al, 1992; AIUM, 1993; Holland et al, 1996).

Although the numbers of alveoli within a lung lobule are relatively constant among species, there is a distinct difference in the structure and arrangement of the bronchioles supplying the gas-exchange area, including the type of terminal bronchioles and the extent of smooth muscle tissue incorporated along the length of the alveolar ducts (Mercer and Crapo, 1992). For humans and nonhuman primates, smooth muscle fibers extend along the terminal generations of the alveolar ducts, whereas in the mouse, these fibers do not extend past the bronchiole-alveolar duct junction.

These findings may suggest that there is a greater potential for hemorrhage and tissue destruction in the mouse lung, particularly where the terminal airways are shorter, thinner, and, perhaps, less distensible than in humans (Tarantal and Canfield, 1994). Morphologic studies have shown that capillaries within the alveolar septa of most mammals are arranged as a single layer separated from the air spaces by a thin cellular barrier (alveolar epithelium and capillary endothelium unit [possibly nanometers in thickness]) (Mercer and Crapo, 1992). Due to this epithelial-endothelial cell configuration, it is plausible that these regions are more susceptible to conditions under which bubble oscillation and tissue injury may occur, with a greater degree of damage possible when lung tissues have less ability to expand (less compliance or elasticity in response to injury). There appear to be no differences, among species or within a species based on age, in endothelial cell morphology or in capillary bed perfusion patterns within visceral pleura and adjoining alveolar septa, which could, at this time, account for differences in susceptibility to ultrasound (Mercer and Crapo, 1992; Voelkel, 1992).

Another important factor specific to the lung may be the monolayer of lung surfactant within the alveolus (Tarantal and Canfield, 1994). As the alveolar lining fluid, lung surfactant is responsible for reducing the surface tension of the aqueous alveolar hypophase, thereby promoting lung expansion and preventing lung collapse (Hawgood and Shiffer, 1991; Singh and Katyal, 1992). At this time, there appear to be no applicable biological differences in the chemical constituents of lung surfactant that could account for differences in susceptibility to ultrasound (Singh and Katyal, 1992; Simon, 1992a; Simon, 1992b). The existence of bubbles within the surfactant layer that could be involved in cavitation phenomena is unknown.

In addition, reports have shown a direct correlation between a reduction in the cavitation threshold and reduced surface tension (Holland and Apfel, 1989). It is possible that, during exposure to ultrasound, small microbubbles are created within corners of the surfactant-rich alveolus (location of Type II alveolar epithelial cells). These microbubbles, if they exist, may oscillate, with localized disruption of the epithelial-endothelial barrier and subsequent leakage of red blood cells. In species in which the alveoli are small (e.g., adult mouse alveolar diameter ≈40 μm) and less distensible, damage may be greater, which could explain why the outcome of exposure to ultrasound in the mouse is more severe than in the monkey (e.g., alveolar diameter ≈120 μm) (Mercer and Crapo, 1992). This hypothesis stems from the fact that alveolar size (diameter) appears to be directly correlated with pleural and alveolar septal thickness and structural fiber composition and deposition in these layers. Species with smaller alveoli have less structural fibers (collagen and elastic fibers) within alveolar septa; therefore, septa may be less distensible and less able to withstand the application of sudden displacement phenomena.

Studies to date, based on the evaluation of innate anatomic and histologic differences and experimental data, suggest that the site of lesion initiation and propagation is in the microvasculature of the visceral pleura and contiguous alveolar septa (Penney et al, 1993; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995). The lung is covered by a well-defined membrane, the visceral pleura, which is illustrated in Figure 3-1. The visceral pleura serves an important role in pulmonary homeostasis related to the mechanical aspects of respiration and as a structural barrier to disease (Tyler and Julian, 1992; Plopper and Pinkerton, 1992). The thickness of the visceral pleura varies dramatically among mammalian species (Tyler and Julian, 1992). As already discussed, such differences allow for the categorization of mammals into two distinct species groups: those with a thin visceral pleura (≈10–25 μm thick) and those with a thick visceral pleura (≈100–150 μm thick or greater). In general, the thickness of the visceral pleura increases as the size (weight) of the animal increases in comparison with other mammalian species and, within limits, is predetermined by the size of the animal, as the animal develops and ages. The structure of the visceral pleura and its relationship to lung parenchyma and the microvasculature of the visceral pleura and alveolar septal capillaries are illustrated in Figure 3-1.

Because the mesothelial layer appears to be quite similar among all mammalian species, species differences in susceptibility to ultrasound-induced damage do not appear to be attributable to events initiated in the mesothelial layer. It appears more likely that differences in lung susceptibility to ultrasound-induced injury are attributable to structural (anatomic) differences in the thickness of the visceral pleura (Fig. 3-3), as determined by the amount and composition of the connective tissue and, possibly, the elastic fibers forming the supporting layer of the mesothelium (Pohlhammer and O’Brien, 1981; Tyler and Julian, 1992; Watson, 1992; Crouch and Parks, 1992). Mice, rats, rabbits, cats, dogs, and monkeys, which are members of the thin group, have scant but varying quantities of collagen fibers within the visceral pleura. Sheep, pigs, humans, cattle, horses, and other large animals, which are members of the thick group, have abundant but varying quantities of collagen fibers within the visceral pleura (Tyler and Julian, 1992).

Figure 3-3.

Visceral pleura (arrows), lung. Differences in visceral pleural thickness among common mammalian species. In all species, the surface is covered by a similar layer of mesothelium. Note that the mouse (M) and rabbit (R) are in the thin group, and the rabbit visceral pleura is slightly thicker than that of the mouse. The pig (P), human (H), and cow (C) are in the thick group. There appears to be little difference in the capillaries and lymphatic vessels within all pleura. The visceral pleura is contiguous with alveolar septa, which contain abundant capillaries and some collagen fibers. H&E stain, bar = 25 μm.

Extrapolation of results from studies that have examined species thresholds for both CW and pulsed ultrasound suggests that susceptibility to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage can be inversely correlated with the thickness of the visceral pleura (Child et al, 1990; Penney et al, 1993; Raeman et al, 1993; O’Brien and Zachary, 1994a; O’Brien and Zachary, 1994b; Tarantal and Canfield, 1994; Frizzell et al, 1994; Zachary and O’Brien, 1995; Raeman et al, 1996; Baggs et al, 1996; Dalecki et al, 1997a, 1997b; O’Brien and Zachary, 1997). Thus, species in the thick group appear more resistant to ultrasound-induced lung damage, whereas those in the thin group appear more susceptible to such damage. The thickness of the visceral pleura appears directly linked to the quantity and organization of collagen deposited during growth and maturation of this layer (Pohlhammer and O’Brien, 1981; Plopper and Pinkerton, 1992; Tyler and Julian, 1992; Watson, 1992; Crouch and Parks, 1992; Sahebjami, 1992). The capillaries and lymphatic vessels within this layer appear to be the same, structurally, for all of these species (Kay, 1992; Mercer and Crapo, 1992; Pinkerton, Gehr, and Crapo, 1992; Voelkel, 1992). Endothelial cells are the principal targets for ultrasound-induced injury in lung. From a structural (anatomical or histological) basis, there are no apparent gross, subgross, or microscopic differences in endothelial cells between and among species that presently could explain species differences in susceptibility to ultrasound-induced injury. Although there are likely cellular, subcellular, and molecular differences in endothelial cells between and among species, these differences are unlikely to play important roles in species differences in susceptibility to ultrasound-induced injury.

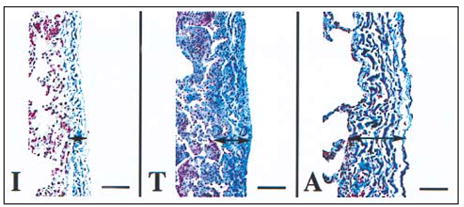

The results of the application of a special stain for collagen fibers (Masson’s trichrome), to lung tissue sections allows the investigator to identify the quantity and distribution of collagen fibers in the visceral pleura and alveolar septa (Fig. 3-4). This histochemical stain labels collagen fibers (connective tissue) blue. Collagen fibers are abundant in those species within the thick group, such as pigs, humans, and cattle. Collagen fibers are minimal in species within the thin group, such as mice and rabbits. The amount and distribution of collagen fibers within alveolar septa, in both the thin and thick groups, appear to be directly proportional to the amount and distribution of collagen fibers within the visceral pleura. It is plausible that this collagen may provide stability to the alveolar septa, may play a role in the lung’s elasticity, and may be related to tissue injury associated with ultrasound (Watson, 1992).

Figure 3-4.

Visceral pleura (arrows), lung. Differences in visceral pleural collagen deposition (blue fibers) among common mammalian species. Note that the mouse (M) and rabbit (R) of the thin group lack appreciable quantities of collagen fibers in the visceral pleura and alveolar septa. The pig (P), human (H), and cow (C) of the thick group have abundant collagen fibers in the visceral pleura and alveolar septa. The visceral pleura is contiguous with alveolar septa, which contain proportional quantities of collagen fibers. Masson's trichrome stain, bar = 25 μm.

The visceral pleura also contains an additional group of structural fibers—elastic fibers—which may influence species-specific differences in the susceptibility of the lung to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage. Elastic fibers are able to stretch and recoil and thus likely play an important role in respiration and in the elasticity of mammalian lung (Watson, 1992). The quantity of elastic fibers in the visceral pleura appears to parallel the amount of collagen fibers and the overall thickness of the visceral pleura in mammalian species. Thus, species with more elastic fibers (the thick group) appear to be more resistant to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage, while species with fewer elastic fibers (the thin group) appear to be more susceptible to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage. More detail on exposure conditions and lesions in reference to the thin and thick issue is provided in Section 4.

The arrangement and distribution of elastic fibers, as well as differences among species, are illustrated in Figure 3-5. These fibers likely play an important role in the elasticity of the lung and its ability to respond to injury and forces that may alter normal distention of individual alveoli.

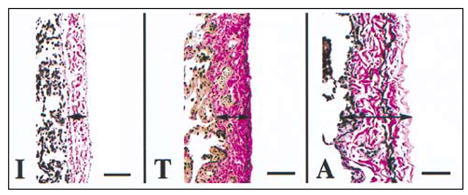

Figure 3-5.

Visceral pleura (arrows), lung. Differences in visceral pleural elastic fiber deposition (black fibers) among common mammalian species. Note that the mouse (M) and rabbit (R) of the thin group lack appreciable quantities of elastic fibers in the visceral pleura. The pig (P), human (H), and cow (C) of the thick group have abundant elastic fibers in the visceral pleura. The visceral pleura is contiguous with alveolar septa, which contain proportional quantities of elastic fibers. Note the arrangement of elastic fibers in a layer or lamina extending through the visceral pleura parallel to the surface of the lung. Collagen fibers stain red with this stain. Verhoff Van Gieson stain, bar = 25 μm.

For a single mammalian species of the five discussed here, the thickness of the visceral pleura varies depending upon age (Sahebjami, 1992). In general, the visceral pleura of younger animals is thinner than those of more mature animals. Such differences allow for the categorization of individuals based on age and their potential susceptibility to ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage. Lung hemorrhage has been induced in neonatal (Baggs et al, 1996) and young (Dalecki et al, 1997c) pigs with diagnostic ultrasound. Lung hemorrhage has been induced in adult pigs with 30 kHz CW ultrasound but not with 3 or 6 MHz pulsed ultrasound (Zachary and O’Brien, 1995; O’Brien and Zachary, 1996; O’Brien and Zachary, 1997). More detail on exposure conditions and lesions in reference to the thin and thick issue is provided in Section 4. Differences in responses to diagnostic ultrasound within the same species, based on age, may again be linked to specific tissue properties (Sahebjami, 1992). The thickness of the visceral pleura of pigs as a function of age is illustrated in Figure 3-6. Neonatal or young pigs (less than 2 wk of age [≈1 d, ≈3 d, and ≈12 d old]) have a thinner visceral pleura than that of the juvenile (≈3 mo old) or adult (≈3 yr old) pigs. The developmental process apparently results in a maturation of the visceral pleura accompanied by increased thickness, as well as increased quantities and organization of collagen fibers in older animals (Dunnill, 1962; Hislop et al, 1984; Sahebjami, 1992).

Figure 3-6.

Visceral pleura (arrows), pig lung. Differences in visceral pleural thickness based on age in pigs. The visceral pleura of young animals (1 day [1d], 3 days [3d], and 12 days [12d]) is thinner than that of older animals (3 months [3m] and 3 years [3y]). H&E stain, bar = 25 μm.

Similar differences based on age appear to exist in the visceral pleura of humans. Figure 3-7 illustrates that infants have a thinner visceral pleura than older humans and that the thickness of the visceral pleura increases with age. Thickness differences related to age could account for the differential sensitivity of newborn, young, and adult pig lung to diagnostic ultrasound-induced hemorrhage. The increase in thickness of the visceral pleura related to development appears associated with increased deposition (quantity) and organization (maturation) of structural proteins (fibers) within this layer. In addition, there appears to be a unique organization of elastic fibers into a distinct and continuous lamina in the outer layer of the visceral pleura with development. Elastic fibers may play a critical role in lung responses to ultrasound with regard to innate elasticity of lung in response to tissue distortion. The results of the application of a special stain for collagen (Masson’s trichrome stain) shows that human infants (Fig. 3-8) and young pigs (Fig. 3-9) have less collagen in the visceral pleura compared with older individuals, with the quantity of these specific fiber types increasing with development. In addition, the results of the application of special stains for elastic fibers (Verhoeff Van Gieson stain) illustrates that human infants (Fig. 3-10) and young pigs (Fig. 3-11) have fewer elastic fibers within their visceral pleura when compared with older individuals; with the quantity and organization of this specific fiber type increasing with age.

Figure 3-7.

Visceral pleura (arrows), human lung. Differences in visceral pleural thickness based on age in humans. The visceral pleura of younger humans (infant [I]) is thinner than that of older humans (teenager [T] and adult [A]). H&E stain, bar = 67 μm.

Figure 3-8.

Visceral pleura (arrows), human lung. Differences in the quantity of collagen fibers (blue staining fibers) in humans based on age. Note that the infant (I) visceral pleura has less collagen fibers than the teenager (T) and adult (A) and that the amount of collagen fibers and the organization of this layer increase with age. The collagen fibers are present within alveolar septa and also increase in quantity with age. Masson’s Trichrome stain, bar = 67 μm.

Figure 3-9.

Visceral pleura (arrows), pig lung. Differences in the quantity of collagen fibers (blue fibers) in pigs based on age. Note that the 1 (1d), 3 (3d), and 12 (12d) day old pigs have a visceral pleura that contains less collagen fibers than the 3 month (3m) and 3 year (3y) old pigs and that the quantity and organization of collagen fibers increases with age. The collagen fibers are present within alveolar septa and also increase in quantity with age. Masson's trichrome stain, bar = 25 μm.

Figure 3-10.

Visceral pleura (arrows), human lung. Differences in the quantity of elastic fibers (black staining fibers) in humans based on age. Note that the infant (I) has less elastic fibers than the teenager (T) and adult (A) and that the number of elastic fibers increases with age. The elastic fibers in the infant are not well organized when compared with the well-organized layer of elastic fibers in the outer zone of the visceral pleura in the teenager and the adult. Collagen fibers stain red with this stain. Verhoff Van Gieson stain, bar = 67 μm.

Figure 3-11.

Visceral pleura (arrows), pig lung. Differences in the quantity of elastic fibers (black fibers) in pigs based on age. Note that the 1 (1d), 3 (3d), and 12 (12d) day old pigs have less elastic fibers than the 3 month (3m) and 3 year (3y) old pigs. The elastic fibers increase in quantity with age. The elastic fibers in the 1, 3, and 12 day old pigs are not well organized when compared with the well-organized layer of elastic fibers in the outer zone of the visceral pleura in the 3 month and 3 year old pigs. Verhoff Van Gieson stain, bar = 25 μm.

There have been very few measurements reported of the ultrasonic propagation properties of the region between the skin of the thoracic wall (ventral, lateral, or dorsal) and the pleural surfaces, e.g., the chest wall (intercostal tissue) (Child et al, 1990; Raeman et al, 1993; Tarantal and Canfield, 1994; Harrison et al, 1995; Baggs et al, 1996; O’Brien and Zachary, 1997; Dalecki et al, 1997c). Table 3-3 summarizes the available data dealing with ultrasound and the chest wall. These limited data suggest that the thickness of the chest wall plays a minor role in susceptibility to bioeffects induced by ultrasound among species or within species based on age.

Table 3-3.

Summary of Ultrasonic Properties of Chest Walls

| Species | Age | Thickness (mm) | Frequency (MHz) | Measured Loss (dB) | Estimated Loss or Attenuation Coefficient | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | 7 wk | NA | 1.1 | 1.5–5.2 | NA | Child et al, 1990 |

| 3.4 | 2.5–6.9 | NA | ||||

| Mouse | NA | NA | 1.1 | NA | 1.9 dB/cm-MHz | Raeman et al, 1993 |

| Monkey | 1 d–16 yr | 4–5 | NA | NA | Tarantal and Canfield, 1994 | |

| Younger | 3–12 | 4–5 | NA | NA | Tarantal and Canfield, 1994 | |

| Older | 8 | 4–5 | NA | NA | Tarantal and Canfield, 1994 | |

| Minipig | 5–6 mo | 21 | NA | NA | NA | Harrison et al, 1995 |

| Crossbred pig | 1–2 d | 7–8 | 2.3 | 2–18 | 1.1–1.3 dB/cm-MHz | Baggs et al, 1996 |

| Young pig | 10 d | 7–8 | 2.3 | 2–18 | 1.1–1.3 dB/cm-MHz | Dalecki et al, 1997c |

| Mouse | 6–7 wk | 2 | 3 & 6 | NA | 1 dB/cm-MHz | O’Brien and Zachary, 1997 |

| Rabbits | 5.5 mo | 9.6–16 | 3 & 6 | NA | 1 dB/cm-MHz | O’Brien and Zachary, 1997 |

| Crossbred pig | 10–12 wk | 19–24 | 3 & 6 | NA | 1 dB/cm-MHz | O’Brien and Zachary, 1997 |

NA, data not available

3.1.2 Intestine

The major segments of the intestinal tract that can be exposed to diagnostic ultrasound during examination include the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, cecum, and colon. These segments have similar morphologic features and include an outer serosal covering (peritoneum), longitudinal and circular smooth muscle layers, a submucosal layer, a muscularis mucosae, and a lamina propria and its covering—the mucosal epithelium (Fig. 3-12). Although all segments have mucosal glands (crypts or pits), the stomach, colon, and cecum lack villi—the finger-like projections covered by epithelial cells that protrude into the lumen. In all segments, the luminal content is separated from the intestinal tissue by a uniform layer of mucosal epithelial cells, which are supported by a highly vascular capillary bed within the lamina propria. Mucus, as well as ingesta and gas bodies, is present within intestinal segments; however, the content of mucus and ingesta may vary from segment to segment due to peristalsis. Gas bodies, therefore, can be spatially associated with the luminal surfaces of intestinal epithelial cells.

Figure 3-12.

Intestine (colon), pig. The surface of the intestine is covered by a uniform layer of mesothelium (M), which is similar among all species discussed herein. The next layer from the mesothelium (M) to the lumen are longitudinal (L) and circular (C) smooth muscle, submucosa, muscularis mucosae, and the mucosa (Mu). The mucosa consists of a uniform layer of epithelium that separates the intestine from luminal content (Lu) and a highly vascular lamina propria with abundant capillary beds. H&E stain, bar = 80 μm.

Hemorrhage has been induced in the intestine by pulsed ultrasound and piezoelectric lithotripsy in mice (Dalecki et al, 1995b; Dalecki et al, 1995c; Dalecki et al, 1996; Miller and Geis, 1998d). These lesions appear to be associated with the mucosal surface and not the serosal surface of the intestine. Hemorrhage occurs in the mucosal-submucosal layer, and blood is evident within the lumen. At present, there are no data indicating any significant differences among species or within a species based on age in the susceptibility to ultrasound-induced intestinal hemorrhage. In addition, data are not available documenting specific innate anatomic differences, such as peritoneal thickness or smooth muscle layer thickness in the intestine, that could account for any potential differences in susceptibility to ultrasound. The normal morphologic features of intestine (colon) are shown in Figure 3-12.

There are, however, structural differences among species in intestine that potentially could influence the induction of bioeffects (Fig. 3-13 and Fig. 3-14). These innate differences could include the thickness of the serosal covering (peritoneum) of the intestine, including the amount of structural fibers (collagen, elastin), as well as quantity of longitudinal and circular smooth muscle in subjacent layers. In addition, each of these layers must be thought of as an independent unit with individual (layer-specific) responses to ultrasound based on tissue composition and vascular supply. Initial morphologic evaluation of the intestine suggests that smaller species, such as mouse and rat, have thinner serosal coverings and fewer structural fibers in this layer and less prominent longitudinal and circular smooth muscle layers compared with the larger animal species, such as pigs and humans.

Figure 3-13.

Small intestine (L = lumen of the intestine). The mesothelium, muscle layers, submucosa, and the muscularis mucosae are thinner in the mouse (M) than in the pig (P). H&E stain, bar = 80 μm.

Figure 3-14.

Colon (L = lumen of the colon). The mesothelium, muscle layers, submucosa, and the muscularis mucosae are thinner in the mouse (M) then in the pig (P). H&E stain, bar = 80 μm.

It also is plausible that differences in the thickness, composition, and structural maturation of these various layers will increase based on age and stage of development. These differences, if they exist and how and if they are related to susceptibility to ultrasound, remain to be investigated.

3.2 Tissues Without Well-Defined Gas Bodies

Transcutaneous, transesophageal, transvaginal, and transrectal approaches to ultrasound diagnosis present potential sources of exposure to tissues without well-defined gas bodies such as nervous tissue, liver, kidney, and reproductive tissues. Lesions in tissues without well-defined gas bodies include cell and tissue destruction and necrosis with accompanying hemorrhage in nervous tissue, liver, kidney, and reproductive tissues. Although lesions have been reported in these tissues, there are no scientific data demonstrating differences among species or within species based on age in response to ultrasound in these tissues at this time. Data reflecting differences in tissue properties have not been compiled for these tissues. These properties generally include the thickness and composition of protective membranes, which include capsular coverings (peritoneum, tunica albuginea) and associated connective tissue in such organs as the liver, kidney, and testis, and the calvarium, vertebral column, dura mater, and associated connective tissue in such organs as the brain and spinal cord. Preliminary evaluation of these tissues and their properties suggest there are important differences among species or within species based on age in the thickness, as well as composition, of these protective layers. These anatomical and morphological differences in tissue properties appear to correspond to differences in tissue properties that exist between species in the lung.

Footnotes

Figures in this section serve solely to demonstrate the concepts presented throughout this section. The concepts are based on published and experience-based but empirical observations of the relative (qualitative) differences among species and within the same species and are not based on quantitative data. Quantitative data, collected from measurements made on large numbers of animals providing actual measurements of specific tissue or organ structures or properties, do not appear to exist in the scientific literature.