Abstract

There is convincing evidence about the benefits of exercise training in community dwelling frailer older people, but little evidence that this intervention can be delivered in general practice. In this prospective cohort study in 14 general practices in north London we assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of a tailored exercise referral programme for frail elderly patients delivered within a variety of inner city primary care settings. One hundred and twenty-six women and 32 men aged 75 years and older, deemed borderline frail by their GPs, took part in a two-phase progressive exercise programme (Stage 1 — primary care setting; Stage II — leisure/community centre setting) using the Timed Up And Go (TUG) test as the primary outcome measure. Baseline TUG measures confirmed that the participants were borderline frail and that GP selection was accurate. Of those referred by their GP or practice nurse 89% took up the exercise programme; 73% completed Stage I and 63% made the transition to the community Stage II programme. TUG improved in Stage I with a mean difference of 3.5 seconds (P<0.001). An individually tailored progressive exercise programme following GP referral, delivered in weekly group sessions by specialist exercise instructors within general practices, was effective in achieving participation in exercise sessions and in improving TUG values in a significant number of frailer older citizens.

Keywords: exercise, general practice, older people

INTRODUCTION

Exercise training is recognised as a powerful therapeutic intervention for inactive older people, particularly individually tailored physical activity programmes that incorporate specific balance and strength training exercises.1,2 Although referral for supervised exercise by GPs has been explored in general patient populations,3 the means of engaging frailer older people with more complex pathologies in the necessary strength training requires further investigation.2 In this brief report we describe a targeted, tailored exercise training programme for frail older people delivered in group sessions within general practices.

METHOD

The exercise sessions were funded by a Health Action Zone, and took place in 14 practices. Because the evaluation measured clinical practice against standards and included no activities impinging on older people over and above a recognised and proven clinical intervention, it fulfilled the British Geriatric Society criteria for audit.4 GPs had access to exercise prescription schemes, delivered in community-based classes in local leisure centres, and the only innovation in this project was in the place of treatment. They gained consent to exercise therapy from their patients directly, as in any kind of ‘normal care’ process.

Patients were referred for exercise by the GPs and practice nurses according to specified health and physical activity criteria,5 which required referrers to make clinical judgements about the frailty of their older patients. After a pilot phase to test the feasibility, acceptability and sustainability of the intervention, functional gains were monitored at baseline using the Timed Up and Go test (TUG),6 and at follow-up for those who transferred to community classes. The TUG test measures the time in seconds taken to get up from a chair without arms, walk 3 metres, turn round, return to the chair and sit down, and is a predictor of falls risk.

The exercise sessions occurred once weekly for 8 weeks, consisted of chair-based strengthening exercises, and were followed by a transition to further chair-based exercise classes in local community settings. The classes were designed to include supervised exercise, social opportunities and education, and have been shown to work well with vulnerable older patients in both secondary and primary care.7 The exercise programme was tailored to each patient's expressed needs, goals, and wishes, and their progress as judged by the class instructor. Participants were encouraged to perform the exercises three times per week (once in the group and two further sessions at home following written instructions). Patients were supported by telephone contact during both the practice-based sessions and in the transition phase.

How this fits in

Exercise training is beneficial for inactive older people, and can be delivered in primary care. However, its therapeutic effects in frail older people have not been explored. This study shows that targetted exercise for frail older people can be delivered in general practice with evidence of effectiveness.

RESULTS

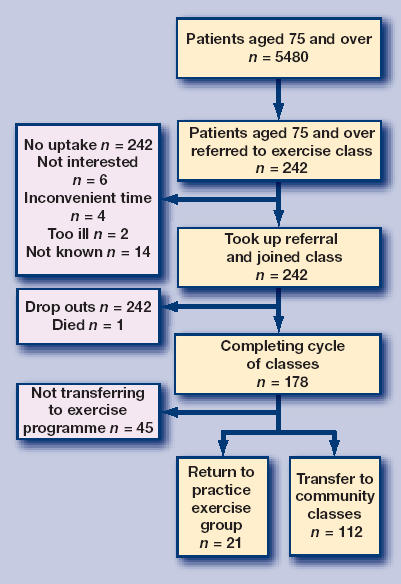

The total number of people aged 75 years and over in participant practices was 5480. We obtained a referral for 242 patients (4.4% of the total) over an 18-month period, and 216 took up the referral (87%). One hundred and thirty-five women and 43 men (74% of those referred) completed the cycle of exercise classes. Of these, 21 men and 78 women were aged 75–79 years, 9 men and 37 women were aged 80–84 years and 12 men and 21 women were aged 85 years or more. At the end of the practicebased exercise classes 112 older people (46% of the referred group) transferred to community classes, and 21 (9%) who were either not ready or not willing to transfer returned to practice-based classes; 45 (19%) declined further involvement in further exercise programmes. The progress of these individuals through the exercise programme is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Progress of the individuals through the exercise programme.

TUG scores were obtained at baseline and follow-up for 13 men and 37 women aged 75–79 years, four men and 15 women aged 80–84 years and three men and four women aged 85 years and over, from the group who transferred to community classes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of initial timed get up and go scores for community dwelling older citizens and those graduating from practice-based to community-based classes.

| Age in years | Range of normative scores in seconds | Mean scores in seconds at beginning of intervention (range) | Mean scores in seconds at end of intervention (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75–79 male | 4.6–7.2 | 14.8 (6–40) | 11.5 (5–34) |

| 75–79 female | 5.2–7.4 | 14.3 (7–33) | 11.4 (6–31) |

| 80–84 male | 5.2–7.6 | 9 (7–11) | 8.5 (7–9) |

| 80–84 female | 5.7–8.7 | 14.4 (9–31) | 10.4 (8–15) |

| 85–89 male | 5.3–8.9 | 10.2 (9–11) | 8.6 (8.4–8.7) |

| 85–89 female | 6.2–9.6 | 20 (14–40) | 16.25 (9–35) |

The TUG scores of those who made the transition to community classes at the end of the practice-based programme showed a statistically significant change over baseline. The mean TUG score before exercise was 14.8 seconds (range = 6–40) and at the end of the programme was 11.3 (range = 5–35), a mean difference of 3.5 seconds (paired two sample t-test, t = 8.2, degrees of freedom = 75, P<0.001). In 23 of the 76 participants for whom we had TUG values, the value was reduced from above to below the cut-off for falls risk (30.3%, 95% CI = 19.9 to 40.7).

DISCUSSION

This pilot study suggests that exercise promotion programmes for frail older people organised within general practice can recruit frail older people and enable many to enrol in community-based exercise classes.

GPs can identify frail older individuals accurately. Not only were the ranges of TUG scores in both sexes and all ages outside the normative ranges, but all women and men aged 75 to 79 years had mean TUG scores at or above the conventional threshold for high risk of falling, of 14 seconds. Women in all age bands were also above the threshold of 12 seconds proposed as normal for community-dwelling older women.8

Concordance with exercise classes and regimes is high within this sub-group, with nearly half of those referred (52% of joiners and 63% of completers) making the transition to communitybased classes. Although apparent benefits (in terms of improved function) were measurable, the TUG scores of frail older people in this programme were not restored to within the normative ranges after completion of the practice-based exercise classes, except in a small group of the oldest men. However, in nearly one third of participants the TUG values fell below the cut-off for falls risk, suggesting that a clinically important gain had been achieved.

Further investigation of the impact of this practice-based group exercise approach on changes in functional ability, falls, quality of life and service utilisation in a population of frail older people appears to be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

We thank Felix Zinc and the Advanced Exercise Instructors of Camden Active Health Team, all the practices who participated in this innovative service, and all the participants for their feedback.

Funding body

Camden & Islington Health Action Zone

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health. National Service Framework for older people: modern standards and service models. London: HMSO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson MC, Devlin N, Gardner MM, Campbell AJ. Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls 1: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:679–701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riddock C. Exercise referral systems. A review. London: The Stationary Office; 2000. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Evaluation Committee. Submission of Clinical Effectiveness Abstracts Criteria for publication in Age & Ageing. www.bgs.org.uk/Clinical%20Effectiveness/BGS%20Meetings/publication_criteria.htm (accessed 23 Aug 2006)

- 5.Department of Health. Exercise referral systems: a National Quality Assurance Framework. London: HMSO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Posiadlo DA, Richardson S. The Timed Up and Go: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elder persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinan S. Physical activity for vulnerable older patients. In: Harries M, Young A, editors. Exercise prescription for patients. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2000. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischoff H, Staehelin H, Monsch A, et al. Identifying a cut-off point for normal mobility: a comparison of the timed ‘up and go’ test in community dwelling and institutionalised elderly women. Age Ageing. 2003;32:315–320. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]