Abstract

Aim: To offer a critique of current methods of defining amblyopia treatment outcome and to examine alternative approaches.

Method: Literature appraisal and descriptive case presentations.

Results: Currently, the outcome of amblyopia treatment is expressed as the number of acuity chart lines gained or, alternatively, achievement of an arbitrarily adopted level of visual acuity. As binocular vision is optimised with equal visual input from each eye the authors propose that the optimum outcome of amblyopia therapy is to achieve a visual acuity in the amblyopic eye equal to that of its fellow. In addition, improvement should be graded as the proportion of change in visual acuity with respect to the absolute potential for improvement (that is, that pertaining in the fellow eye at end of treatment).

Conclusions: There are two methods of appropriately describing the outcome of amblyopia treatment: firstly, by the difference in final visual acuity of amblyopic and fellow eye (residual amblyopia); secondly, the proportion of the deficit corrected.

Keywords: treatment outcome, unilateral amblyopia, children

One of the major challenges facing clinical practice and research in amblyopia is obtaining valid, accurate, and reliable measures by which the outcome of treatment can be quantified. Increasingly, Snellen based visual acuity measurements are being supplanted by charts scaled according to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR),1–3 which allow acuity to be recorded with improved accuracy and sensitivity to detect change.4–6 However, advances in chart design have not impacted on the way in which treatment outcome, either at the level of the individual or group of patients, is quantitatively assessed. In this article we examine several approaches to defining treatment outcome in unilateral amblyopia.

DEFINING OUTCOME

There are two principal and complementary approaches to defining amblyopia treatment outcome: recording the final visual acuity achieved and quantifying the amblyopic deficit corrected.

Final acuity level achieved

Most treatment studies have defined success as the achievement of a specific acuity by the end of the treatment period, usually 6/9 or 6/12.7–13 A few have adopted the arguably more strict criterion of 6/6 (“normal” visual acuity) as their definition of success.14–17 This latter approach assumes normal visual acuity to be a single value that is identical for all populations, whereas in reality, of course, it is represented by a range of values above and below 6/6.5–6,18

From a functional viewpoint, the condition best suited to promote normal visual development and the attainment of full binocular vision is that occurring when the visual input from each eye is equal.19 On this basis we propose that the optimum outcome for children undergoing amblyopia therapy should be a visual acuity in the amblyopic eye equal to that of the fellow, non-amblyopic eye. The discrepancy from this—that is, the difference between the amblyopic eye and fellow eye at the end of the treatment indicates the extent of residual amblyopia. This approach takes into account any visual development that has occurred during the treatment period. Although it must be acknowledged that vision in the fellow eye of individuals with unilateral amblyopia may also be abnormal20–22 it none the less provides a good indication of the best achievable acuity at this stage in development for a given individual. A negative discrepancy will indicate occlusion amblyopia of the fellow eye.

Quantifying the deficit corrected

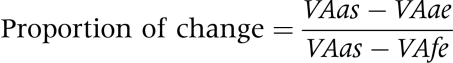

Not every child with amblyopia undergoing treatment responds fully. This has resulted in another often employed outcome measure: the number of acuity chart lines gained (typically three8,23) during treatment. This approach has the drawback that it does not give any indication of how close the outcome acuity is to “normal.” Furthermore it does not indicate the proportion of the amblyopic defect that has been corrected. To overcome these limitations, we propose an alternative approach to defining outcome which quantifies the proportion of the amblyopic deficit corrected by treatment. That is:

|

where VAas is visual acuity of amblyopic eye at the start; VAae is visual acuity of the amblyopic eye at the end of treatment; and, VAfe is visual acuity of fellow eye at the end of treatment.

This formula (for ease and standardisation, visual acuity scores should be in logMAR values) also takes into account any visual development that might naturally occur in the fellow eye during the treatment period. A score of 1.0 represents the optimum outcome, where the amblyopic deficit has been fully corrected, and the visual acuity of the previously amblyopic eye equals that of its fellow.

To illustrate these different approaches, consider two children with amblyopia (cases 1 and 2). Both responded to treatment by an improvement of 0.3 log units (three chart lines), which in many studies would be considered an identical gain. However, case 1 improved from 6/60 to 6/30 (1.0 to 0.7 logMAR), while case 2 improved from 6/12 to 6/6 (0.3 to 0.0 logMAR). Both cases had fellow eyes with acuities of 6/6 (0.0 logMAR) at the end of treatment. For case 1 a three line improvement has corrected 30% (0.3) of the deficit, a clinically subnormal outcome, whereas case 2, a three line improvement has corrected 100% (1.0) of the deficit and the acuity of the two eyes is now equal. The drawback of the proportional improvement approach is that subjects developing occlusion amblyopia will have a misleadingly elevated proportional improvement.

DISCUSSION

The aforementioned methods of defining treatment outcome are compared and contrasted in Table 1. To highlight the practical application of the outcome definitions, seven illustrative clinical examples are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Methods of defining treatment outcome. (Proposed optimum expressions of outcome appear in lower shaded portion of the table)

| Definition of treatment outcome | Disadvantage | Advantage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Examples of theoretical cases with amblyopia during treatment

| Case | Amblyopic eye (start) | Amblyopic eye (end) | Fellow eye (start) | Fellow eye (end) | ⩾6/9 | ⩾3 lines | Residual amblyopia | Proportional improvement |

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.7 | 0.05 | 0.0 | No | Yes | 0.70 | (1.0−0.7)/(1.0−0.0) = 0.30 |

| 2 | 0.30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Yes | Yes | 0.0 | (0.3−0.0)/(0.3−0.0) = 1.00 |

| 3 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.20 | −0.18 | No | No | 0.79 | (0.72−0.62)/(0.72 to −0.18) = 0.11 |

| 4 | 0.20 | 0.0 | 0.06 | −0.04 | Yes | No | 0.04 | (0.2−0.00)/(0.2 to −0.04) = 0.83 |

| 5 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 0.30 | −0.3 | Yes | Yes | 0.45 | (0.90−0.15)/(0.90 to −0.3) = 0.63 |

| 6 | 1.0 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.25 | No | Yes | 0.1 | (1.00−0.35)/(1.00−0.25) = 0.87 |

| 7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Yes | Yes | −0.1 | (0.9−0.1)/(0.9−0.2) = 1.14 |

Outcomes for each case are presented according to each of the four methods of defining successful outcomes (achievement to 6/9 or better, improvement by three or more lines, residual amblyopia, and proportional improvement calculations).

Proportional improvement can be equivalently expressed in percentage.

A proportional outcome >1.0 signifies visual acuity of the once amblyopic eye improving to levels higher than that of the fellow eye while a negative proportional outcome signifies deterioration of the amblyopic eye during treatment.

CONCLUSION

We have reviewed several different approaches to quantifying treatment outcome in unilateral amblyopia, and describe their relative advantages and disadvantages based on case simulations. We conclude that the optimum approach requires an expression of (i) the difference in final visual acuity between the amblyopic and fellow eye (residual amblyopia) and (ii) the proportion of the amblyopic deficit corrected by treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey IL, Lovie JE. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1976;53:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovie-Kitchin JE. Validity and reliability of visual acuity. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1988;8:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGraw PV, Winn B. Glasgow acuity cards: a new test for the measurement of letter acuity in children. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1993;13:400–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGraw PV. Studies of human macular function: developmental anomalies. PhD Thesis. Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University, 1995.

- 5.McGraw PV, Winn B, Gray LS, et al. Improving the reliability of visual acuity measures in young children. Ophthal Physiol Opt 2000;3:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kheterpal S, Jones HS, Moseley MJ, et al. Reliability of visual acuity in children with reduced vision. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1996;16:447–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson C, Cleary M, Winn B. Is there a significant relationship between inter-ocular acuity difference and the degree of anisometropic ametropia? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:S940. [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Paediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomised trial of atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiscox FD, Strong JR, Minshull C, et al. Occlusion for amblyopia: a comprehensive survey of outcome. Eye 1992;6:300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latvala M, Paloheimo M, Karma A. Screening of amblyopic children and long-term follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1996;74:488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn JT, Cassady JC. Current trends in amblyopia therapy. Ophthalmology 1978;85:428–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutschke PJ, Scott WE, Keech RV. Anisometropic amblyopia. Ophthalmology 1991;98:258–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson J. Simple anisometropia and amblyopia. Br Orthopt J 1961;18:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lithander J, Sjöstrand J. Anisometropic and strabismic amblyopia in the age group 2 years and above: a prospective study of the results of treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 1991;75:111–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epelbaum M, Milleret C, Buissenes P, et al. The sensitive period for strabismic amblyopia in humans. Ophthalmology 1993;100:325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulton AB, Mayer DL. Esotropic children with amblyopia: effects of patching on acuity. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1988;226:309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mintz-Hitner HA, Fernandez KM. Successful amblyopia therapy initiated after age 7 years: compliance cures. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:1535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart CE. Comparison of Snellen and log-based acuity scores for school-aged children. Br Orthopt J 2000;57:32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Noorden GK. Binocular vision and ocular motility. 4th ed. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1990.

- 20.Wali N, Leguire LE, Rogers GL, et al. CSF interocular interactions in childhood amblyopia. Optom Vis Sci 1991;68:81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo GC, Irving E. The amblyopic eye of a unilateral amblyope: a unique entity. Clin Exp Optom 1991;74:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giaschi DE, Regan D, Kraft SP, et al. Defective processing of motion-defined form in the fellow eye of patients with unilateral amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992;33:2483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan JH, Thompson JR, Gottlob I. Differences in management of amblyopia between European countries. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:S398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]