Abstract

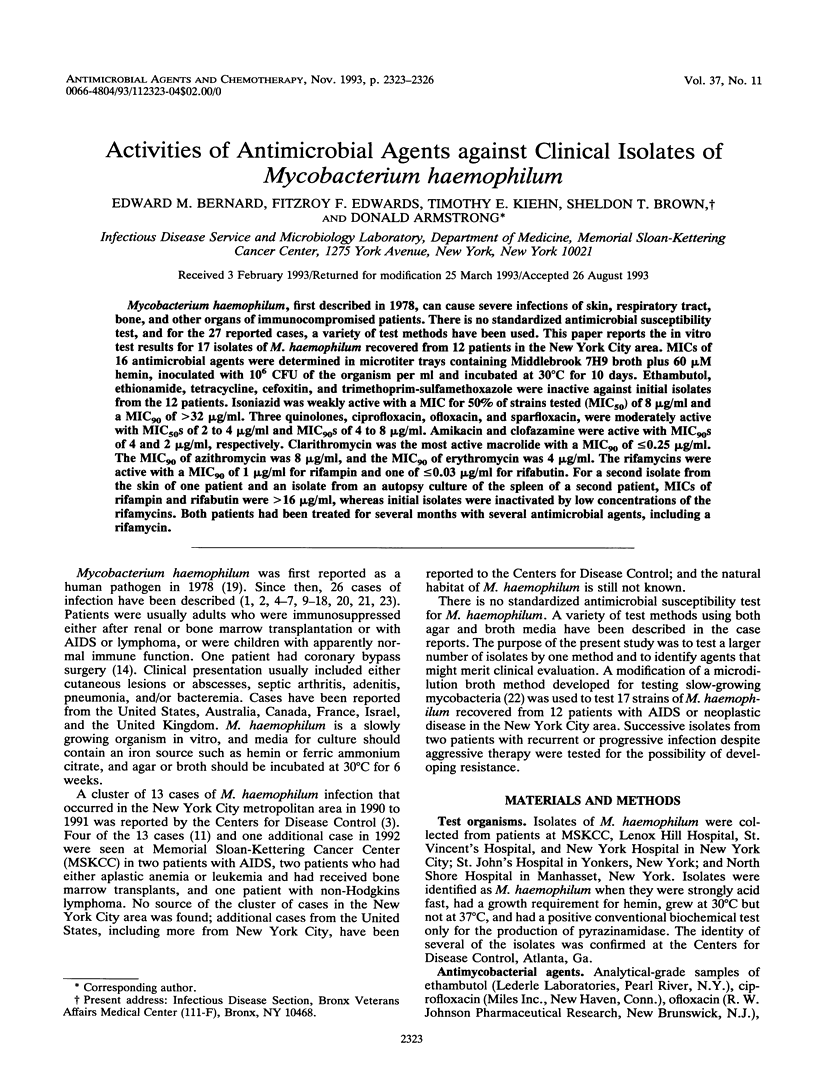

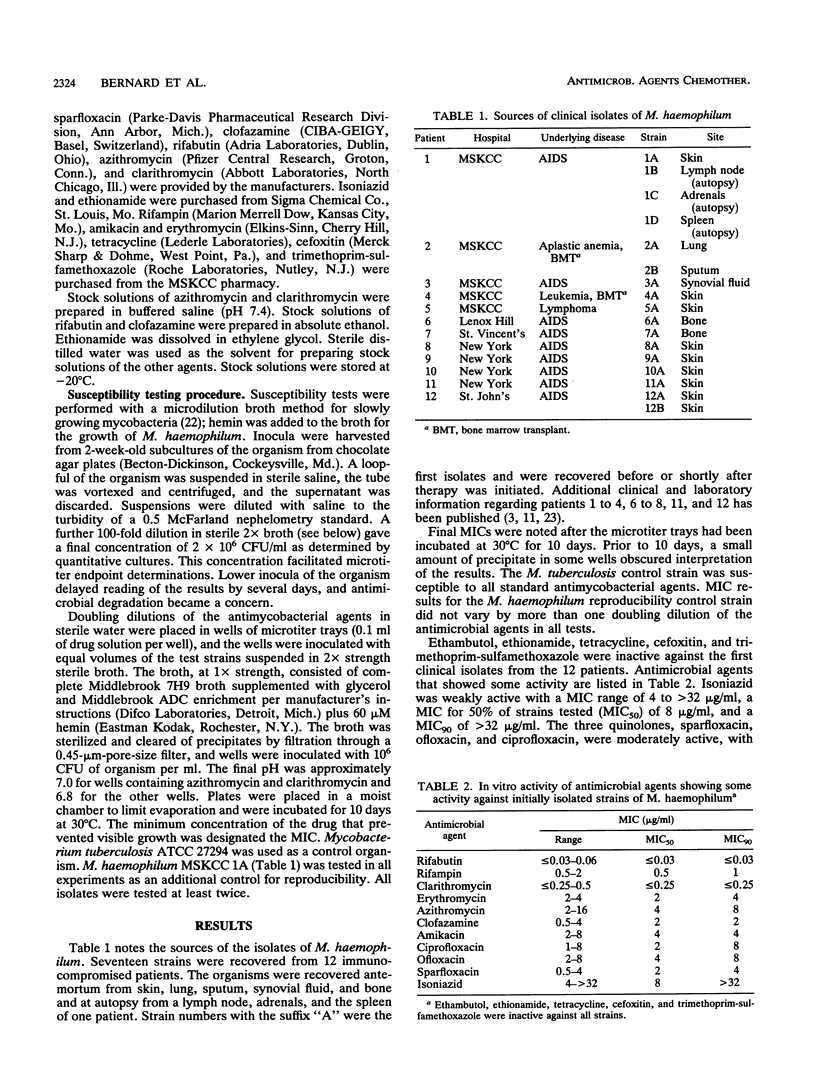

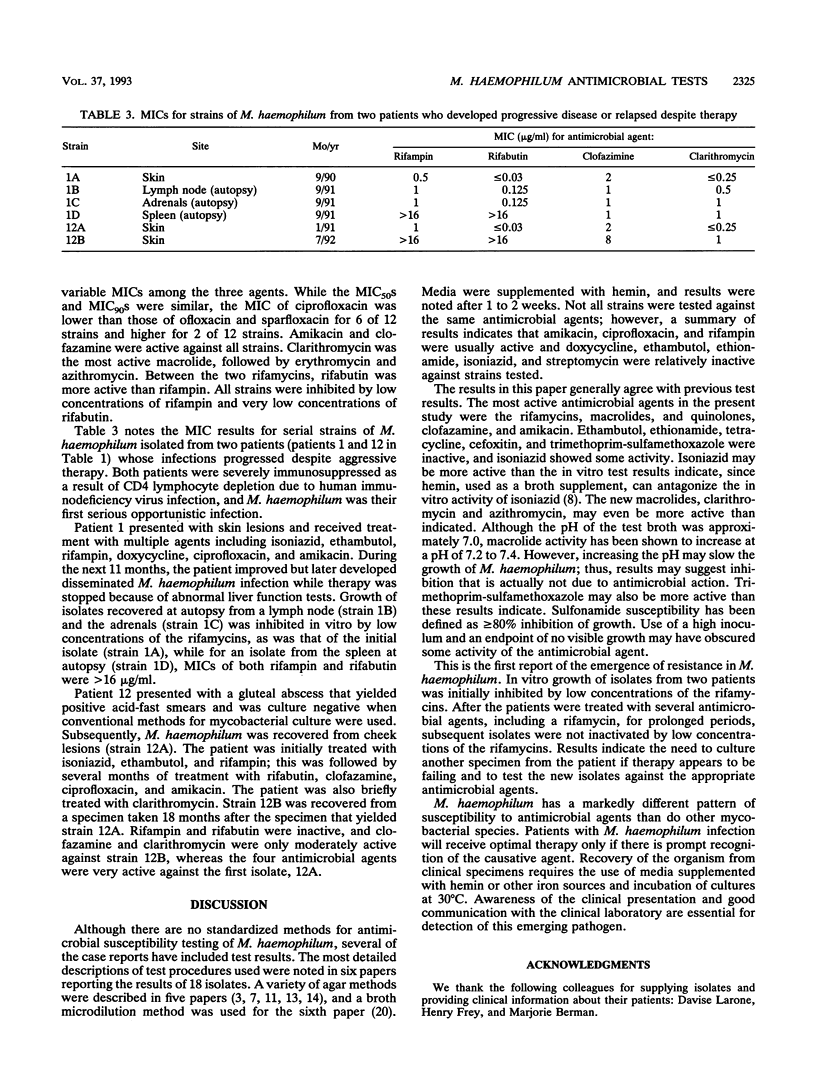

Mycobacterium haemophilum, first described in 1978, can cause severe infections of skin, respiratory tract, bone, and other organs of immunocompromised patients. There is no standardized antimicrobial susceptibility test, and for the 27 reported cases, a variety of test methods have been used. This paper reports the in vitro test results for 17 isolates of M. haemophilum recovered from 12 patients in the New York City area. MICs of 16 antimicrobial agents were determined in microtiter trays containing Middlebrook 7H9 broth plus 60 microM hemin, inoculated with 10(6) CFU of the organism per ml and incubated at 30 degrees C for 10 days. Ethambutol, ethionamide, tetracycline, cefoxitin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were inactive against initial isolates from the 12 patients. Isoniazid was weakly active with a MIC for 50% of strains tested (MIC50) of 8 micrograms/ml and a MIC90 of > 32 micrograms/ml. Three quinolones, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and sparfloxacin, were moderately active with MIC50s of 2 to 4 micrograms/ml and MIC90s of 4 to 8 micrograms/ml. Amikacin and clofazamine were active with MIC90s of 4 and 2 micrograms/ml, respectively. Clarithromycin was the most active macrolide with a MIC90 of < or = 0.25 microgram/ml. The MIC90 of azithromycin was 8 micrograms/ml, and the MIC90 of erythromycin was 4 micrograms/ml. The rifamycins were active with a MIC90 of 1 microgram/ml for rifampin and one of < or = 0.03 micrograms/ml for rifabutin. For a second isolate from the skin of one patient and a isolate from an autopsy culture of the spleen of a second patient, MICs of rifampin and rifabutin were > 16 microgram/ml, whereas initial isolates were inactivated by low concentrations of the rifamycins. Both patients had been treated for several months with several antimicrobial agents, including a rifamycin.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Becherer P., Hopfer R. L. Infection with Mycobacterium haemophilum. Clin Infect Dis. 1992 Mar;14(3):793–793. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branger B., Gouby A., Oulès R., Balducchi J. P., Mourad G., Fourcade J., Mion C., Duntz F., Ramuz M. Mycobacterium haemophilum and mycobacterium xenopi associated infection in a renal transplant patient. Clin Nephrol. 1985 Jan;23(1):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B. R., Brumbach J., Sanders W. J., Wolinsky E. Skin lesions caused by Mycobacterium haemophilum. Ann Intern Med. 1982 Nov;97(5):723–724. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. J., Blacklock Z. M., Kane D. W. Mycobacterium haemophilum causing lymphadenitis in an otherwise healthy child. Med J Aust. 1981 Sep 19;2(6):289–290. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb128321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. J., Jennis F. Mycobacteria with a growth requirement for ferric ammonium citrate, identified as Mycobacterium haemophilum. J Clin Microbiol. 1980 Feb;11(2):190–192. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.2.190-192.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever L. L., Martin J. W., Seaworth B., Jorgensen J. H. Varied presentations and responses to treatment of infections caused by Mycobacterium haemophilum in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992 Jun;14(6):1195–1200. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.6.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER M. W. The antagonism of the tuberculostatic action of isoniazid by Hemin. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954 Mar;69(3):469–470. doi: 10.1164/art.1954.69.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouby A., Branger B., Oules R., Ramuz M. Two cases of Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in a renal-dialysis unit. J Med Microbiol. 1988 Apr;25(4):299–300. doi: 10.1099/00222615-25-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton J., Nye P., Miller R. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in a patient with AIDS. J Infect. 1991 Nov;23(3):303–306. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(91)93080-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn T. E., White M., Pursell K. J., Boone N., Tsivitis M., Brown A. E., Polsky B., Armstrong D. A cluster of four cases of Mycobacterium haemophilum infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993 Feb;12(2):114–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01967586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson M., Bieluch V. M., Byeff P. D. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in immunocompromised patients: case report and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(5):906–910. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.5.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Males B. M., West T. E., Bartholomew W. R. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1987 Jan;25(1):186–190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.186-190.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride M. E., Rudolph A. H., Tschen J. A., Cernoch P., Davis J., Brown B. A., Wallace R. J., Jr Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for cutaneous Mycobacterium haemophilum infections. Arch Dermatol. 1991 Feb;127(2):276–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezo A., Jennis F., McCarthy S. W., Dawson D. J. Unusual mycobacteria in 5 cases of opportunistic infections. Pathology. 1979 Jul;11(3):377–384. doi: 10.3109/00313027909059014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulsdale M. T., Harper J. M., Thatcher G. N., Dunn B. L. Infection by Mycobacterium haemophilum, a metabolically fastidious acid-fast bacillus. Tubercle. 1983 Mar;64(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(83)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P. L., Walker R. E., Lane H. C., Witebsky F. G., Kovacs J. A., Parrillo J. E., Masur H. Disseminated Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in two patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1988 Mar;84(3 Pt 2):640–642. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. G., Dwyer B. W. New characteristics of Mycobacterium haemophilum. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Oct;18(4):976–977. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.4.976-977.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibert L., Lebel F., Martineau B. Two cases of Mycobacterium haemophilum infection in Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Mar;28(3):621–623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.621-623.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walder B. K., Jeremy D., Charlesworth J. A., Macdonald G. J., Pussell B. A., Robertson M. R. The skin and immunosuppression. Australas J Dermatol. 1976 Dec;17(3):94–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1976.tb00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. J., Jr, Nash D. R., Steele L. C., Steingrube V. Susceptibility testing of slowly growing mycobacteria by a microdilution MIC method with 7H9 broth. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Dec;24(6):976–981. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.976-981.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarrish R. L., Shay W., LaBombardi V. J., Meyerson M., Miller D. K., Larone D. Osteomyelitis caused by Mycobacterium haemophilum: successful therapy in two patients with AIDS. AIDS. 1992 Jun;6(6):557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]