Abstract

siRNAs targeted to gene promoters can direct epigenetic modifications that result in transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. It is not clear whether the antisense strand of the siRNAs bind directly to DNA or to a sense-stranded RNA transcript corresponding to the known promoter region. We present evidence that an RNA polymerase II expressed mRNA containing an extended 5′ untranslated region that overlaps the gene promoter is required for RNA-directed epigenetic modifications and transcriptional silencing of the RNA-targeted promoter. These promoter-associated RNAs were detected by their hybridization to the antisense strand of the complementary promoter-directed siRNA. Antisense phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides were used to degrade the promoter-associated RNA transcripts, the loss of which abrogated the effect of siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing, as well as the complexing of the siRNA with the silent state histone methyl mark and the promoter-associated RNA. These data demonstrate that low-copy promoter-associated RNAs transcribed through RNAPII promoters are recognized by the antisense strand of the siRNA and function as a recognition motif to direct epigenetic silencing complexes to the corresponding targeted promoters to mediate transcriptional silencing in human cells.

Keywords: CCR5, epigenetic, histone methylation, siRNa, transcription

The histone code was proposed to explain the role of epigenetic modifications of histones in gene regulation (1). Control of the histone code through specific targeted epigenetic marks could prove invaluable for long-term modulation of gene expression in treating diseases involving deregulated genes. However, the underlying mechanism responsible for governing the histone code is not yet well understood. Recently, it has become clear in human cells that siRNAs can modulate gene transcription in both a suppressive and activating manner through epigenetic modifications (2–4) suggestive of a role for RNA in directing the histone code. In human cells, RNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) (2) can be initiated through promoter-targeted siRNAs and requires Argonautes 1 and 2 (5, 6). The resulting siRNA-targeted promoter exhibits a silent state histone methyl mark containing both histone H3 lysine-9 di-methylation (H3K9me2) and histone H3 lysine-27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) (7, 8). Furthermore, RNA polymerase II appears to be required for siRNA-mediated TGS in both Schizosaccharomyces pombe (9, 10) and human cells (6, 7). However, exactly how the siRNAs recognize and modulate TGS through histone methylation specifically at the targeted promoter has remained unclear. In S. pombe, transcription through the targeted genomic region is required for TGS (11), suggesting that there might also be a role for transcription through promoter regions in human cells.

Results and Discussion

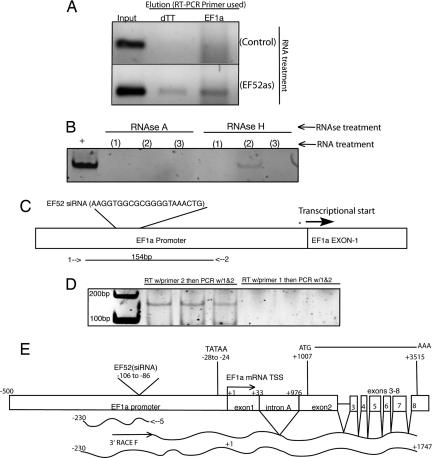

To determine whether TGS of the elongation factor 1 alpha promoter (EF1a) in human cells (2) involves an RNA transcribed through the promoter, we performed a pull-down assay using various species of 5′ biotin-linked RNAs that target the EF1a promoter [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]. Interestingly, we observed that only the 5′ biotin-linked antisense strand of the EF1a promoter-targeted siRNA consistently eluted with a low-copy RNA transcript corresponding to the EF1a promoter [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. This EF1a promoter-associated RNA was detected by reverse transcription (RT), using either a polydTT or an EF1a promoter-specific primer (Fig. 1A). The detection of the promoter-associated RNA in elutes from pull-downs was inhibited by RNase A and resistant to RNase H treatment (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the antisense RNA-mediated pull-down was specifically an RNA/RNA interaction and not an RNA/DNA interaction and that this RNA contained a poly(A) tail. To reconfirm the pull-down assay, we performed directional RT-PCR on total RNA extracted from cell cultures (Fig. 1C). Supporting observations with the pull-down assay, only the antisense primer (relative to the direction of mRNA transcription) was capable of amplifying the EF1a promoter-associated RNA (Fig. 1D), which when sequenced exhibited direct sequence homology to the known EF1a promoter (GenBank accession no. DQ503424).

Fig. 1.

Detection and characterization of a EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant. (A) 5′ biotin-linked antisense RNAs targeted to the EF1a promoter elute with a promoter-associated RNA. Cultures were treated with either EF52 siRNA containing a 5′ biotin-linked sense annealed to the antisense (Control) or 5′ biotin-linked antisense RNA alone (EF52) (100 nM Lipofectamine 2000). Samples from the preelution step (Input) are shown along with the post-biotin/avidin elution (Elution). The elutes were collected 24 h after transfection, DNase treated, subject to RT with either a random hexamer primer (dTT) (BioRad; iScript), or EF1a-specific primer (EF1a) that spans the EF1a promoter/exon 1 junction (SI Table 2, no. 804) and PCR amplified with EF1a-specific primers (SI Table 2, 803/804). (B) The 5′ biotin tagged antisense RNA eluted EF1a promoter-associated RNA is sensitive to RNase A and resistant to RNase H treatment. Sample lanes represent elutes from cultures treated with (1) EF52 sense RNA + 5′ biotin linker, (2) EF52 antisense RNA + 5′ biotin linker, and (3) EF52 sense RNA plus 5′ biotin linker annealed to the EF52 antisense plus 5′ biotin linker. The resultant elutes underwent RT (BioRad; iScript) followed by PCR (SI Table 2, EF1a-specific primers 803/804) after the various RNase treatments. (C) Characterization of the EF1a promoter-associated RNA as determined by bidirectional RT-PCR. RT was performed on DNase treated 293T cell RNA with various primers either sense (1) or antisense (2) (SI Table 2, 803 or 805, respectively) followed by PCR with both primers. (D) RT with primer 2 followed by PCR with primers 1 and 2 generates a ≈156-bp band corresponding to the EF1a promoter whereas RT with primer 1 followed by PCR with primers 1 and 2 does not. The results from three independent cultures are shown. (E) 5′ and 3′ RACE analysis of the EF1a promoter-associated RNA was performed on 293T cell RNA with EF1a primers specific for the promoter-associated RNA. The 5′ RACE analysis was performed with primer 5 (SI Table 2, EFpRNARev), whereas the 3′ RACE analysis was performed with the 3′RACE F primer (SI Table 2). The resulting RACE products were cloned, sequenced, and shown to be spliced and processed accordingly and to contain a 5′ UTR which overlaps ≈230 bp of the EF1a promoter.

The observation that there is transcriptional activity across the EF1a promoter suggested that a species of RNA is generated specifically to promoter regions. To characterize the 5′ end and transcription start site (TSS) of this EF1a promoter-associated RNA, 5′ RACE was performed. The 5′ RACE procedure identified the promoter-associated RNA TSS to be ≈230 bp upstream of the previously described TSS for EF1a (Fig. 1E; GenBank accession no. DQ642693) in a region that does not appear to be required for promoter activity (12).

Although the 5′ RACE indicated substantial overlap with the defined EF1a promoter (12), the 3′ end remained unknown. To determine whether the promoter-associated RNA was linked to the mRNA coding region 3′ RACE was performed by using primers defined from the previously performed 5′ RACE (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, the 3′ RACE product produced a transcript that contained both the newly defined upstream 5′ UTR of the EF1a promoter-associated RNA and the intron-spliced and -processed EF1a mRNA (Fig. 1E; GenBank accession no. EF362804). The 5′ and 3′ RACE sequence data thus suggested that this promoter-associated RNA was in essence a variant mRNA that contained an extended 5′ UTR (≈230 bp upstream of the transcription start site) and was functional, because it was spliced and processed in a manner similar to RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) transcribed EF1a transcripts (Fig. 1E).

The requirement for a biotin-linked pull-down assay to detect this RNA variant suggested that the expression level of the promoter-associated RNA variant is relatively low compared with mRNA expression levels. To determine the prevalence of the endogenous EF1a promoter-associated RNA, we performed quantitative RT-PCR for EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant and mRNA in five different cell types. On average, there was ≈571 EF1a mRNA copies/promoter-associated RNA variant copy (Table 1). Taken together, these observations suggest that an EF1a promoter-associated low-copy sense-stranded RNA, with an extended 5′ UTR, is present and interacts with the antisense strand of the EF1a promoter-targeted siRNA, supporting findings depicting a functional role for the antisense strand of siRNAs and RNAPII in TGS of human cells (7).

Table 1.

Expression patterns of mRNA and promoter-associated RNAs (pRNAs)

| Cell Type | EF1a mRNA | EF1a pRNA | EF1amRNA/pRNA | p16 mRNA | p16 pRNA | p16 mRNA/pRNA | NF-kB (p105) mRNA | NF-kB (p105) pRNA | NF-kB (p105) mRNA/pRNA | Cyclin D1 mRNA | Cyclin D1 pRNA | Cyclin D1 mRNA/pRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 293T | 258.816 | 0.440 | 588.133 | 0.106 | 0.051 | 2.070 | 8.088 | 0.080 | 100.426 | 12.691 | 0.002 | 5595.300 |

| 293-R5-GFP | 812.252 | 2.960 | 274.374 | 0.541 | 0.235 | 2.297 | 7.546 | 0.110 | 68.593 | 5.154 | 0.008 | 630.345 |

| 1G5 | 267.943 | 0.644 | 415.873 | Undetectable | Undetectable | Undetectable | 4.978 | 0.007 | 699.412 | 0.010 | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| THP-1 | 2000 | 2.577 | 776.046 | Undetectable | Undetectable | Undetectable | 11.048 | 0.198 | 55.715 | 1.642 | Undetectable | Undetectable |

| BJ (primary cells) | 241.484 | 0.471 | 512 | Undetectable | Undetectable | Undetectable | 3.906 | 0.016 | 230.720 | 85.377 | 0.006 | 12854.625 |

| HuVEC (primary cells) | 353.553 | 0.4105 | 861 | 0.035 | 0.038 | 0.9 | 3.400 | 0.025 | 132.513 | 19.915 | 0.053 | 374.805 |

The mRNA and pRNA expression for EF1-alpha, p16, NF-kB (p105 subunit), and Cyclin D1 was determined by real-time quantitative PCR and standardized to GAPDH from RNA isolated from various human cell lines and primary cells.

The extent of transcription through RNAPII promoters is currently unknown. To determine how ubiquitous these promoter-associated RNA variants are, we surveyed various cell types, using quantitative RT-PCR. We screened the EF1a, p16, NF-κB, and Cyclin D1 promoters to contrast mRNA and promoter-associated RNA variant expression levels standardized to GAPDH mRNA levels in 293T, 293-R5-GFP, 1G5, and THP-1 cell lines and primary cell types BJ and HuVEC. In the cell types examined, each assayed gene exhibited similar mRNA to promoter-associated RNA variant ratios (Table 1), further supporting the 5′ and 3′ RACE data that suggests promoter-associated RNA variant expression is linked with mRNA expression across various genes in numerous cell types.

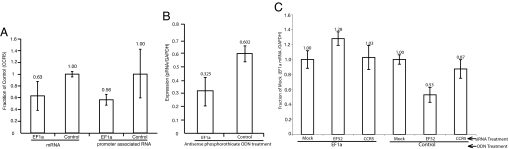

Next, we investigated whether the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant was susceptible to siRNA-mediated targeting and suppression. Transient transfections of synthetic EF1a-targeted siRNAs demonstrated a reduction in both the EF1a promoter-associated RNA and mRNA levels at 24 h after siRNA transfection (Fig. 2A), which was similar to, but not as robust as, previous observations of EF1a TGS observed at 48 h after siRNA transfection (2, 6, 7). These data indicate that the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant, similar to EF1a transcribed mRNAs, is also reduced in expression when targeted by siRNAs.

Fig. 2.

Promoter-associated RNA variant and mRNA expression in siRNA treated cultures. (A) The EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant is reduced (P = 0.352) along with EF1a mRNA expression (P = 0.038) when the promoter is targeted by the EF52 siRNA (EF1a) relative to the CCR5-specific siRNA (Control). Measurements of mRNA or promoter-associated RNA levels from three independent transfections standardized to GAPDH expression with the standard error of the means (SEM) are shown with P values reported for a single-sided F test (mRNA) and double-sided t test (promoter-associated RNA). (B) Treatment with an EF1a-specific (EF1a) antisense phosphorothioate ODN suppresses EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant expression whereas the CCR5-specific ODN (Control) does not. 293T cells were transfected with either an ODN targeted to the EF1a promoter (EF1a) or to the CCR5 promoter (CCR5) (100 nM Lipofectamine 2000). Twenty-four hours later, the cultures were collected, cell RNA was isolated, Dnase was treated, and EF1a promoter-associated RNAs were assessed by qRT-PCR relative to GAPDH expression. Triplicate treated cultures were assessed and the standard error of the means is shown. (C) Treatment of cells with the EF1a promoter-targeted ODN (EF1a) suppresses siRNA (EF52)-mediated transcriptional silencing of the EF1a gene, whereas the control CCR5 ODN (Control) does not. EF1a mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR at 18 h after siRNA transfection in untreated (Mock) and cells treated with either EF52 (EF52) or control (CCR5) siRNAs, which was 42 h after ODN transfection and standardized to GAPDH expression. Results are from triplicate transfections, and the standard deviations are shown.

To ascertain the requirement of the promoter-associated RNA variants for the induction of siRNA-mediated TGS, we performed a blocking experiment in which antisense phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) (13) were designed to recognize the cognate promoter-associated RNA variant sequence for either the EF1a or CCR5 promoters. The CCR5 promoter was recently shown to be susceptible to siRNA-directed TGS (6) in a manner similar to observations with EF1a (2). Phosphorothioate ODNs operate by Watson–Crick hydrogen bonding to inhibit RNA expression by activation of the RNase H pathway, which cleaves the targeted RNA at the heteroduplex site (14). When promoter-associated RNA variant expression was directly assessed in phosphorothioate ODN treated cultures, there was a specific and significant reduction in promoter-associated RNA expression of both the EF1a (Fig. 2B) and CCR5 promoter-associated RNAs (SI Fig. 7A) after ODN treatment. The suppression of the EF1a promoter-associated RNA by ODN treatment did not significantly reduce the downstream EF1a mRNA expression (SI Fig. 8). These data suggest that the phosphorothioate ODNs are functional in suppressing promoter-associated RNA expression for either EF1a or CCR5.

To determine the ability of EF1a promoter-directed siRNAs to modulate TGS in the absence of the low-copy EF1a promoter-associated RNA, cultures were first treated with the EF1a-specific ODN followed by a transfection with the EF1a-targeted siRNAs (either antisense RNA or siRNA). Interestingly, there was a concurrent loss of RNA-mediated TGS, whereas the control, ODNs-targeted to the CCR5 promoter, had no effect on RNA-directed transcriptional silencing of the EF1a promoter (Fig. 2C and SI Fig. 7B). The EF1a-specific ODN treatment was also effective at suppressing the detection of the EF1a promoter-associated RNAs in the 5′ biotin pull-down assay, whereas the control ODN had no effect (SI Fig. 9). A similar observation of ODN-mediated blocking of TGS was observed when the CCR5-specific ODN was used to block RNA targeting of the CCR5 promoter (SI Fig. 7B). Overall, these data indicate that EF1a and CCR5 promoter-associated RNA variants play a functional role in the induction of RNA-mediated TGS in human cells.

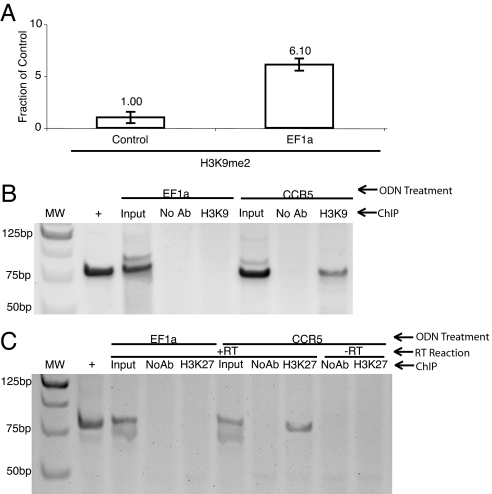

TGS in human cells has been shown to operate through epigenetic modifying complexes and specifically correlate with a corresponding silent state histone code at the siRNA-targeted promoter (5–7). To determine the requirement of the promoter-associated RNA variant in directed epigenetic modifications that can result in gene regulation, dual pull-down experiments were performed. Suppression of the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant expression by ODN treatment resulted in a loss of siRNA-directed H3K9me2 at the siRNA-targeted EF1a promoter (Fig. 3A) and an inability to elute the EF1a-targeted promoter with H3K9me2 and the EF1a-specific 5′ biotin-linked RNA (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that siRNA-targeted chromatin remodeling complexes require the promoter-associated RNA to modulate epigenetic modifications, but do not directly link the promoter-associated RNA with the respective silent state chromatin mark for the targeted gene. To determine whether the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant is directly linked to the respective silent state chromatin mark a dual pull-down assay was performed, followed by DNase treatment of the elutes, which were then assayed specifically for the promoter-associated RNA variant. Interestingly, when the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant was suppressed by ODN treatment there was no detectable EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant in the dual pull-down whereas the control was capable of eluting the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant along with the H3K27me3 silent state epigenetic mark (Fig. 3C). These data directly link the 5′ biotin-linked antisense strand of the EF1a-targeted RNA, the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark, and the EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant and support the notion that the promoter-associated RNA variant described here is required for RNA-directed silent state histone methyl marks and transcriptional silencing in human cells.

Fig. 3.

The EF1a promoter-associated RNA is required for RNA-directed epigenetic modifications at the EF1a promoter. (A) The EF1a promoter-targeted ODN (Control) suppresses EF52 siRNA-directed H3K9me2 at the siRNA-targeted EF1a promoter, whereas treatment with the CCR5 promoter-specific ODN followed by treatment with EF52 siRNA (EF1a) does not. Results from two independent experiments with the respective ranges are shown. (B) Treatment of cultures with the EF1a promoter-targeted ODNs (EF1a) suppresses the dual pull-down (ChIP) of H3K9me2 followed by 5′ biotin-linked antisense RNA, whereas the treatment with a CCR5 promoter-specific ODN (CCR5) does not. Undiluted inputs (Input), no antibody controls (No Ab), a positive PCR control using an EF1a containing plasmid (+), and molecular weight standards are also (MW) shown. Results from a single experiment are shown and demonstrate that the H3K9me2, 5′ biotin-linked antisense EF1a-specific RNA, and EF1a promoter (DNA) coimmunoprecipitate. (C) The EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant coimmunoprecipitates with the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark and the 5′ biotin-linked antisense EF1a-specific RNA. Dual pull-down assays were performed on 293T cultures treated with either the EF1a-specific (EF1a) or CCR5-specific (CCR5) ODNs (100 nM) transfected 4 h later with the 5′ biotin-linked EF1a-specific antisense RNA (EF52as, 100 nM). Twenty-four hours later, cultures were collected and an H3K27me3 immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed followed by a biotin/avidin pull-down on the H3K27me3 elutes. The resultant elutes were then subject DNase treatment, and a reaction was carried out with or without reverse transcriptase (+RT or −RT, respectively). The samples were then subject to nested PCR specific for the promoter-associated EF1a RNA variant. The result from one of two such experiments is shown.

We describe here that the EF1a, CCR5, p16, NF-κB, and Cyclin D1 RNAPII promoters in various human cell lines and primary cells contain corresponding RNA transcripts, overlapping their respective promoter regions and in particular the promoter-directed siRNA target sites for EF1a and CCR5. These promoter-associated RNA variants are recognized by the antisense strand of promoter-targeted siRNAs and are reduced after siRNA treatment concomitantly with mRNA expression levels. These data suggest that promoter-associated RNA variants transcribed through RNAPII promoters are recognized by the antisense strand of the siRNA, and possibly other forms of antisense RNA, to mediate epigenetic modifications at the RNA-targeted loci in human cells. Indeed, species of RNA similar to promoter-associated RNA variants have been observed to span intergenic regions and appear to be coupled to chromatin remodeling complexes in controlled expression of repetitive RNA genes in human cells (15, 16), although in the human dihydrofolate reductase gene, a noncoding upstream initiated RNA has been shown to act as a promoter interfering transcript (17) and in S. pombe a similar RNA has been shown to be involved in argonaute-mediated slicing and transcriptional silencing (11). Interestingly, higher order chromatin structures appear to contain an uncharacterized RNA component that may function as a scaffolding in chromatin remodeling (18). These data, along with observations that antisense transcription appears to be ubiquitous in human cells (19), are suggestive of an endogenous mechanism by which antisense RNAs can function by interactions with the promoter-associated RNA variants to direct specific epigenetic modifications in human genetic diseases (20, 21), gene regulation (22, 23), and possibly be used in establishing or maintaining HIV-1 latency (24). Indeed, the antisense strand of the siRNA is required to initiate TGS in human cells (7), suggesting a biological function for the sense-stranded promoter-associated RNA variants described here. Interestingly, the antisense strand of siRNAs appear to be more stable and preferentially compartmentalized within the cell (25), possibly implicating a role for antisense RNAs in regulating pseudogenes (26) or retroelements in human cells (27) putatively through interactions with promoter-associated RNA variants spanning these genomic regions.

A model has begun to emerge that is based on initial work in S. pombe and expounded on here that explains the functional and mechanistic role of the promoter-associated RNA variants in RNA-mediated transcriptional gene regulation in human cells. The promoter-associated RNA model of transcriptional silencing might function by RNAPII reading through the promoter, transcribing a relatively low-copy promoter-associated RNA variant, which can become bound by targeted antisense RNAs (Fig. 4). The promoter-associated RNA variant and antisense RNA complex might then associate with the local chromatin architecture through a yet-to-be defined chromatin remodeling complex possibly containing DNMT3A. DNMT3A has been shown to bind siRNAs (28) and coimmunoprecipitate with the antisense strand of EF1a promoter-specific siRNAs and H3K27me3 at the targeted EF1a promoter (7). This bound complex could then permit the docking of a chromatin remodeling complex that can initiate the writing of a silent state histone code at the targeted promoter and possibly spreading distal of the siRNA-targeted site in a 5′-3′ manner along with transcription (6, 7). Such a scenario would accommodate previous observations in which siRNAs have been shown to interact with various components of chromatin remodeling complexes (5–7). Of significant interest is the role DNMT3A might play in siRNA-mediated TGS and/or antisense RNA-directed chromatin modifications. DNMT3A has not only been shown to interact with siRNAs (7, 28) but also to coimmunoprecipitate with the H3K27 methyltransferase EZH2 (29), HDAC-1, and Suv39H1 (30). Moreover, EZH2 and Ago-1 have both recently been observed at siRNA-targeted promoters and suppression of Ago-1 inhibits siRNA-mediated TGS (5, 6), suggesting a link between RNAi and chromatin remodeling components.

Fig. 4.

Model for RNA-directed TGS in human cells. (A) The promoter-associated RNA model of RNA-mediated TGS proposes that a variant species of mRNA, a promoter-associated mRNA, essentially containing an extended 5′ UTR, is recognized by the antisense strand of siRNAs or possibly endogenous antisense RNAs during RNAPII-mediated transcription of the RNA-targeted promoter. (B) The antisense strand of the siRNA might then guide a putative transcriptional silencing complex (possibly composed of DNMT3A, Ago-1, HDAC-1, and/or EZH2) to the targeted promoter where histone modifications result and the initial gene-silencing event. (C) The initial silencing event or prolonged suppression of the siRNA-targeted promoter may result in heterchromatization of the local siRNA-targeted genomic region and is not, based on these data, thought to be the result of slicing of the low-copy promoter-associated RNA but rather due to a recruitment of chromatin remodeling factors or complexes to the targeted promoter that result in the gene silencing event.

The observations presented here, that promoter-associated RNA variants are present at siRNA-targeted promoters, combined with the requirement of RNAPII in siRNA-mediated TGS (6, 7, 10) and the coimmunoprecipitation of DNMT3A and H3K27me3 with siRNAs and the siRNA-targeted promoter (7, 28), provide a link between RNA, chromatin, and gene expression. Overall, these data support a role for siRNAs, and specifically antisense-stranded RNAs, in writing the histone code (1) and the regulation of gene expression. These findings may lead to new therapeutic approaches in directed epigenetic control of gene expression in human cells.

Materials and Methods

ODN Blocking Experiments.

To demonstrate the role of promoter-associated RNA variants in siRNA-mediated TGS antisense phophorothioate ODNs EF52as ODN 5′CAG TTT ACC CCG CGC CAC CTT-3′ and R61as ODN 5′-CAC AAG ATG CCC TCT GGG CTT-3′ were constructed (13) (generated by IDT, Coralville, IA). Next, 293T or 293-R5-GFP cells [5.5 × 105 per well or 4.0 × 106 per 10-cm plate (RT PCR and pull-down assays, respectively)] were plated and, 24 h later, were transfected with the respective ODNs [100 nM (13), Lipofectamine 2000]. Twenty-four to 42 h later, the ODN transfected cultures were transfected with either the respective biotin-linked antisense RNA or siRNAs [30 nM (for qRT-PCR analysis) or 100 nM (for the pull-down blocking assay) Lipofectamine 2000]. Eighteen to 24 h after the siRNA transfection the ODN/siRNA transfected cultures were collected and cell RNA isolated and used in qRT-PCR for EF1a mRNA, EF1a promoter-associated RNA variant, GFP mRNA, or CCR5 promoter-associated RNA variant detection (described in SI Methods). For the ODN blocking of the pull-down assay the cultures were collected, and detection of promoter-associated RNA variants were determined from the promoter-associated RNA pull-down elutes (described in SI Methods).

Dual Pull-Down Assay.

Human fibroblasts 293T or 293-R5-GFP at 4 × 106 per 10-cm plate were transfected in multiple replicates with either 5′ biotin-linked EF52 or 5′ biotin-linked R61 antisense RNAs (IDT) [Lipofectamine 2000; 1:3 Vol:Vol antisense RNA (100 nM) to Lipofectamine]. In the case of the blocked dual pull-down assays, the cultures (4.0 × 106 per 10 cm plate) were first transfected with the respective antisense ODNs (100 nM Lipofectamine 2000) followed 4 h later by a transfection with the 5 biotin-linked antisense RNAs (EF52as or R61as, 100 nM Lipofectamine 2000). Next, the cultures were collected 18–24 h after the final transfection, and a modified ChIP assay was performed. The ChIP assay consisted of first cross-linking the cultures with formaldehyde [1%, 10 min at room temperature (R/T)] and then the addition of glycine at a final concentration (0.125 M, 10 min at R/T). Next, the cells were washed twice in 1× PBS plus 1/1,000 PMSF (stock PMSF at 0.5M) plus 40U Rnase Inhibitor (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA; catalog no. M0307S), resuspended in 600 μl of ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/140 mM NaCl/10% Triton X-100/0.1% NaDeoxycholate/1/1,000 PMSF/40 units RNase inhibitor) and incubated (10 min on ice). The samples were next centrifuged (5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C), resuspended in 600 μl ChIP lysis buffer, incubated (10 min on ice), and then sonicated [Branson 50-cell machine (Branson Ultrasonics Corporation, Danbury, CT), one interval of 20 second constant at an output setting of “3”]. The sonicated samples were then centrifuged (14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) and the supernatants removed and precleared with 30 μl protein A/Salmon Sperm (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY; catalog no. 16-157) (15 min at 4°C, rotating platform). The precleared supernatants were then centrifuged (14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C), and supernatants were removed with the equivalent aliquots (from the precleared supernatants) used. The samples, consisting of the no antibody control and the anti-trimethyl-H3K27 pull-down (H3K27me3), were incubated either without an antibody (no antibody control), or for the H3K9me2 or H3K27me3 samples with the anti-dimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys-9) or trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys-27) (Upstate Biotechnology; catalog nos. 07-441 and 07-449, respectively) for 3 h at 4°C on a rotating platform. The samples were then treated with 20 μl of protein A/salmon sperm (Upstate Biotechnology) (15 min at R/T, rotating platform) then pulled-down (10,000 rpm for 1 min at 4°C) and washed. The washes consisted of two washes with 1 ml of ChIP lysis buffer, two washes with 1 ml ChIP lysis buffer high salt (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/500 mM NaCl/1% Triton X-100/0.1% NaDeoxycholate/1/1,000 PMSF), followed by two washes with 1 ml ChIP wash buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0/250 mM LiCl/0.5% Nonidet P-40/0.5% NaDeoxycholate/1 mM EDTA). For each wash, the samples were incubated (3 min at R/T, rotating platform) followed by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 3 min at R/T). After the final wash the complexes were eluted by two treatments of 100 μl elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0/1% SDS/10 mM EDTA) (10 min, 65°C) followed by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 3 min at R/T). The eluted complexes (200 μl) was then mixed with 200 μl of modified lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40/300 mM NaCl/20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0/2 mM MgCl2). During this same time, 100 μl of avidin labeled magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Lake Success, NY) were washed with 300 μl of modified lysis buffer. The prewashed beads were then exposed to the extracted elute/ modified lysis buffer solution (15 min at R/T under constant motion). After the 15-min incubation, the beads were captured by using a magnetic bead separator (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and washed 3 times with 2× wash buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/0.5M NaCl). After the third wash, the bound beads were eluted by using elution buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.0/1 mM EDTA/2.0M NaCl), incubated at 65°C for 10 min, and separated by using the magnetic bead separator. The final ≈100-μl elute and no antibody control was then assessed for the DNA corresponding to the EF1a promoter by PCR with EF1a promoter-specific primers (SI Table 2, 803 and 804) or Dnase treated (Ambion, Austin, TX; Turbo DNA-free) followed by RT reaction (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; iScript) and a PCR with 803/804 or EF1pRNAFor and EFpRNARev (SI Table 2). To detect the low-copy promoter-associated RNA variant in the dual pull-down assays, a nested PCR was required. The first PCR was carried out with primers 803/804 (SI Table 2), and 5 μl of this reaction used in the second PCR with primers EFpRNAFor and EFpRNARev (SI Table 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John J. Rossi for vibrant discussions that resulted in insights into the mechanism of siRNA-mediated TGS and Paula J. Olecki for artistic assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL83473 (to K.V.M.) and the Stein Endowment Fund at The Scripps Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

- RT

reverse transcription

- R/T

room temperature

- TGS

transcriptional gene silencing.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. DQ503424, DQ642693, and EF362804).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701635104/DC1.

References

- 1.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris KV, Chan SW, Jacobsen SE, Looney DJ. Science. 2004;305:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1101372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE, Corey DR. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:166–173. doi: 10.1038/nchembio860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li LC, Okino ST, Zhao H, Pookot D, Place RF, Urakami S, Enokida H, Dahiya R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17337–17342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janowski BA, Huffman KE, Schwartz JC, Ram R, Nordsell R, Shames DS, Minna JD, Corey DR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nsmb1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, Villeneuve LM, Morris KV, Rossi JJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nsmb1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg MS, Villeneuve LM, Ehsani A, Amarzguioui M, Aagaard L, Chen Z, Riggs AD, Rossi JJ, Morris KV. RNA. 2005;12:256–262. doi: 10.1261/rna.2235106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris KV. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:3057–3066. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buhler M, Verdel A, Moazed D. Cell. 2006;125:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H, Goto DB, Martienssen RA, Urano T, Furukawa K, Murakami Y. Science. 2005;309:467–469. doi: 10.1126/science.1114955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irvine DV, Zaratiegui M, Tolia NH, Goto DB, Chitwood DH, Vaughn MW, Joshua-Tor L, Martienssen RA. Science. 2006;313:1134–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1128813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakabayasi-Ito N, Nagata S. The J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29831–29837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo BH, Bochkareva E, Bochkarev A, Mou TC, Gray DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2008–2016. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal S, Kandimalla ER. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2001;1:197–209. doi: 10.2174/1568009013334160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer C, Schmitz KM, Li J, Grummt I, Santoro R. Mol Cell. 2006;22:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT, Stadler PF, Hertel J, Hackermueller J, Hofacker IL, et al. Science. 2007;316:1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martianov I, Ramadass A, Serra Barros A, Chow N, Akoulitchev A. Nature. 2007;445:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature05519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maison C, Bailly D, Peters AH, Quivy JP, Roche D, Taddei A, Lachner M, Jenuwein T, Almouzni G. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):329–334. doi: 10.1038/ng843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katayama S, Tomaru Y, Kasukawa T, Waki K, Nakanishi M, Nakamura M, Nishida H, Yap CC, Suzuki M, Kawai J, et al. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tufarelli C, Stanley JA, Garrick D, Sharpe JA, Ayyub H, Wood WG, Higgs DR. Nat Genet. 2003;34:157–165. doi: 10.1038/ng1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho DH, Thienes CP, Mahoney SE, Analau E, Filippova GN, Tapscott SJ. Mol Cell. 2005;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buhler M, Mohn F, Stalder L, Muhlemann O. Mol Cell. 2005;18:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang M, Ou H, Shen YH, Wang J, Wang J, Coselli J, Wang XL. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16967–16972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503853102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang QY, Zhou C, Johnson KE, Colgrove RC, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16055–16059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berezhna SY, Supekova L, Supek F, Schultz PG, Deniz AA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;(20):7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600148103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svensson O, Arvestad L, Lagergren J. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang N, Kazazian HH., Jr Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;9:763–771. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffery L, Nakielny S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49479–49487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vire E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, Morey L, Van Eynde A, Bernard D, Vanderwinden JM, et al. Nature. 2005;439(7078):871–874. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuks F, Burgers WA, Godin N, Kasai M, Kouzarides T. EMBO J. 2001;20:2536–2544. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.