Abstract

Alloreactive B cells can contribute to graft rejection. Anti-CD154 treatment together with donor-specific transfusion (DST) results in the long-term survival of MHC-mismatched mouse heart grafts and inhibition of alloantibody production. To characterize the mechanism of B cell tolerance induced by the anti-CD154 and DST, we used 3-83Igi mice, on BALB/c (H-2Kd) background, that express a B cell receptor that reacts with MHC class I antigens H-2Kb. Transplanting C57BL/6 (H-2Kb) hearts into 3-83Igi mice, followed by tolerance induction, resulted in the peripheral deletion of mature but not immature 3-83 B cells. The sustained deletion of mature alloreactive B cells required the presence of the allograft and can be explained by the absence of T cell help.

Keywords: alloantibody, CD154, T cell help, tolerance, transplant

T cells are essential for allograft rejection, but alloantibodies, whose main targets are MHC molecules, can also contribute to acute and chronic graft rejection (1). Clinical studies show a correlation between the presence of anti-HLA antibodies, complement C4d deposition, and graft failure (2, 3). Removal of alloantibodies by i.v. Ig or plasmapheresis or by the depletion of B cells can improve the longevity of transplants (4). In animal models, the major evidence comes from studies using the μMT mice. These mice have a targeted mutation at the transmembrane domain of B cell receptor μ-chain and have defects in B cells and antibody secretion (5), as well as a reduction in T cell and dendritic cell numbers (6). In a mouse cardiac transplant model in which B10.A (H-2a) hearts are transplanted into H-2b μMT mouse, acute rejection is prevented. Passive transfer of complement-activating alloantibodies restores acute rejection, suggesting that antibodies can facilitate the development of acute allograft rejection (7).

Anti-CD154 (CD40 ligand) treatment has been shown to be an effective way of preventing transplant rejection in animal models (8–11). It has been proposed that such treatment impairs the maturation of host antigen-presenting cells, generates tolerogenic dendritic cells, promotes T cell anergy (12) and deletion (13), and induces regulatory T cells (14, 15). Graft survival can be further enhanced by donor-specific transfusion (DST) (16), and in the presence of anti-CD154, the infused DST is presented by host antigen-presenting cells in a tolerogenic manner, resulting in T cell anergy and regulation (17). Blocking CD154–CD40 interaction also prevents the T-dependent humoral responses (18). As a result, alloantibody production is inhibited (19), which can also be important for the long-term survival of allografts. However, the detailed mechanism of how alloreactive B cells are regulated by such costimulation-targeted therapies is not clear.

To characterize the fate of alloreactive B cells after tolerance induction by anti-CD154-based therapy, we took advantage of a B cell receptor transgenic mouse, 3-83Igi (20). This mouse inherits the transgenes that encode the heavy and light chain of a B cell receptor that recognizes the mouse class I MHC molecule H-2Kb. B cells expressing the transgene can develop normally on the BALB/c background but are efficiently regulated by receptor editing on the C57BL/6 background (21). When the Kb antigen is only expressed by the liver hepatocytes, the 3-83 B cells are deleted in the periphery (22). We used 3-83Igi mice on the BALB/c background as recipients of transplanted C57BL/6 hearts. We then induced tolerance with anti-CD154 and DST. The alloreactive 3-83 B cells are easily detected by an anti-idiotype (Id) antibody (23), allowing us to visualize changes in these B cells after tolerance induction. The results of our study showed that alloreactive B cells were specifically deleted in the periphery at the mature stage.

Results

Tolerance Induction by Anti-CD154/DST Resulted in Peripheral Deletion of Alloreactive B Cells.

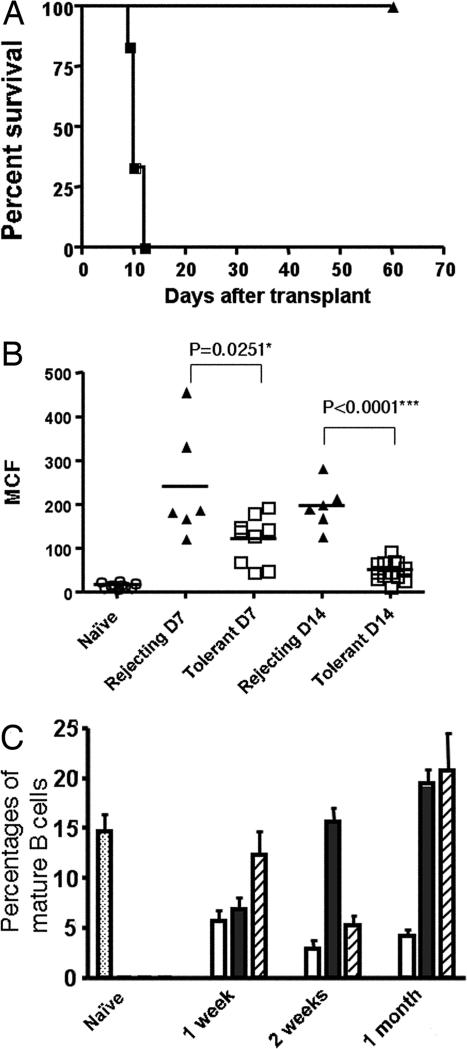

We transplanted C57BL/6 hearts into 3-83Igi mice on a BALB/c background and induced tolerance by treating the mice with anti-CD154/DST. All transplanted grafts survived for >60 days (n = 14). In comparison, mice that received transplant without tolerance induction rejected the grafts within 12 days (n = 6) (Fig. 1A). For those mice that were not killed by day 60, five of six of the grafts survived >90 days. Alloreactive IgM was detected on days 7 and 14 in rejecting mice and was significantly inhibited in tolerant mice (Fig. 1B). IgG from 3-83 B cells were detected in naive 3-83Igi, and there were no significant changes of IgG in the rejecting or tolerant mice compared with naive controls (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Induction of tolerance in 3-83Igi mice and loss of mature B cells in the tolerant mice. (A) Long-term graft survival after treatment of 3-83Igi recipients of C57BL/6 heart grafts with anti-CD154/DST (filled triangles) compared with untreated group (filled squares). (B) Alloreactive IgM antibody titers in naive (open circles), rejecting (filled triangles), or tolerant (open squares) mice (days 7 and 14) measured. Data are shown as mean channel fluorescence (MCF) (n ≥ 6 per group). ∗, Statistically significant; ∗∗∗, very significant. (C) Blood samples were collected at time indicated from naive (dotted bar), tolerant (open bar), and rejecting (filled bar) mice, as well as mice treated with anti-CD154/DST but without transplant (striped bar). Percentages of mature (IgDhighIgMlow) B cells from the lymphoid gate of three to six individual mice are shown.

We observed a substantial loss of mature (IgMlow/IgDhigh) B cells in the peripheral blood in tolerant mice as early as 1 week after transplant; this loss was maintained for the entire 90-day observation period (Fig. 1C and data not shown). In comparison, rejecting mice or mice treated with anti-CD154/DST without heart transplant showed a transient drop of mature B cell numbers ≈1 or 2 weeks, respectively, but recovered by 1 month after the initial treatment (Fig. 1C).

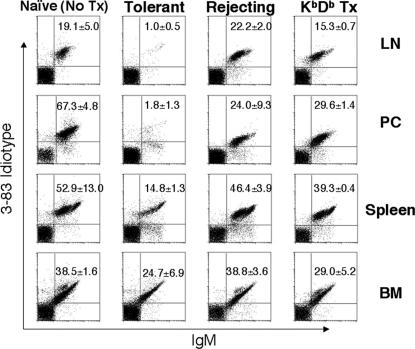

Cells were isolated from the lymph nodes, peritoneal cavity, spleen, and bone marrow 2 months after transplant. Compared with naive mice that did not receive a heart transplant and rejecting mice that received the transplant without tolerance induction, tolerant mice showed an almost complete loss of Id-positive B cells in the lymph nodes and peritoneal cavity (Fig. 2). There was also a significant loss of Id-positive B cells (P < 0.001) in the spleen, but only a relatively modest loss (P = 0.0223) in the bone marrow. The partial B cell loss in the peritoneal cavity of rejecting mice was probably because of the surgical procedure of transplanting the allogeneic heart into the abdominal cavity. To test whether the B cell depletion is antigen-specific and not due solely to anti-CD154 treatment, KbDb knockout mice, which do not express the Kb antigen recognized by 3-83 B cells, were used as heart donors. After transplant and tolerance induction, there was no significant loss of B cells in the lymph node, spleen, or bone marrow (all values of P > 0.05) (Fig. 2, fourth column). The B cell numbers in the peritoneal cavity were also comparable with those in rejecting mice (P = 0.3648). These observations indicate that anti-CD154/DST treatment in the presence of an allograft not expressing specific Kb antigen does not cause 3-83 B cell deletion. Thus only antigen-specific alloreactive B cells were deleted after tolerance induction to heart grafts expressing the Kb antigen.

Fig. 2.

Antigen-specific deletion of 3-83 B cells after tolerance induction. Cells were collected from lymph nodes (LN), peritoneal cavity (PC), spleen, and bone marrow (BM) of naive, tolerant, rejecting (receiving C57BL/6 heart), or tolerant mice receiving hearts from KbDb knockout mice. 3-83 B cells were detected by using anti-IgM and an anti-Id antibody. Data are shown as the average of Id+ B cell percentages from the lymphoid gate (n = 3 per group) ± SD.

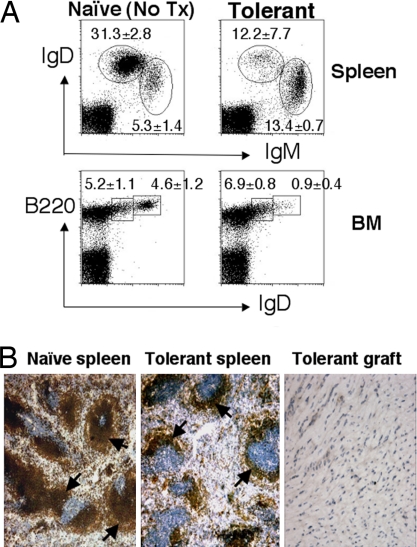

The loss of 3-83 B cells in tolerant mice occurred only in the mature B cell population. We observed a significant reduction in the percentages of mature B cells (IgDhighIgMlow) in the spleen, and of mature recirculating B cells (IgDhighB220high) in the bone marrow (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the percentages of immature B cells (IgDlow) in both spleen and bone marrow were not reduced. Immunohistochemistry confirmed a reduction in the size of B cell follicles in the spleens of tolerant mice compared with those of naive 3-83Igi mice (Fig. 3B). Few B cells were detected in the heart graft, consistent with the notion that the loss of B cells in the lymphoid organs was not because of B cell infiltration into the transplanted graft.

Fig. 3.

Peripheral deletion of mature 3-83 B cells in tolerant mice. (A) Spleen and bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated from tolerant (1 or 2 months after transplant) or control naive 3-83Igi mice and stained with anti-IgM, anti-IgD, and anti-B220 antibodies. Data are shown as the average percentages of mature (IgDhighIgMlow) and immature (IgDlowIgMhigh) B cells from the lymphoid gate in the spleen, as well as mature recirculating (IgDhighB220high) and immature (IgDlowB220low) B cells from the lymphoid gate in the bone marrow ± SD (n = 3–4 per group). (B) Spleen sections of naive (Left) or tolerant (Center) (1 month after transplant) mice were stained with anti-IgM to reveal the size of B cell follicles (dark brown, marked by arrows). (Right) Heart grafts removed from tolerant mice 1 month after transplant and stained with anti-IgM did not show signs of B cell infiltration.

Death of Mature B Cells in the Spleen.

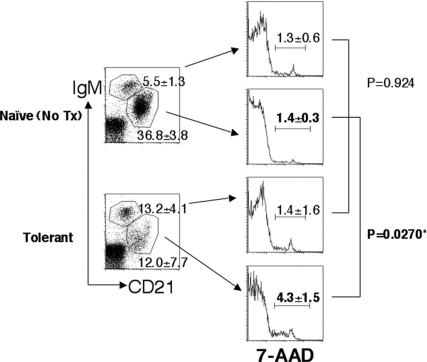

To test the hypothesis that mature B cells underwent deletion in the spleen, we measured the percentages of 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD)-positive dead cells in the mature and immature 3-83 B cell subsets. As shown in Fig. 4, the percentages of dead cells in the immature/transitional (CD21lowIgMhigh) compartment were similar in tolerant and naive mice (1.4 vs. 1.3%; P = 0.9244). Also, the percentages of dead cells in the immature/transitional and mature (CD21highIgMlow) B cell compartment were comparable in the naive mice (1.3 vs. 1.4%; P = 0.8609). In contrast, we observed a significantly increased percentage of 7-AAD-positive dead cells in the remaining mature B cell compartment in the spleen of tolerant mice compared with the same population in naive mice (4.3 vs. 1.4%; P = 0.0270) or to the immature/transitional compartment in tolerant mice (4.3 vs. 1.4%; P = 0.0031).

Fig. 4.

Mature B cell death in tolerant mice. Spleen cells were isolated from tolerant (1 month after transplant) or control naive mice and stained with anti-IgM and anti-CD21 antibodies together with 7-AAD to detect dead cells. 7-AAD staining from mature (CD21highIgMlow) or immature/transitional (CD21lowIgMhigh) B cells from each group are shown in histograms. Data are shown as an average of 7-AAD-positive cell percentages from each gated population ± SD (n = 3). ∗, Statistically significant.

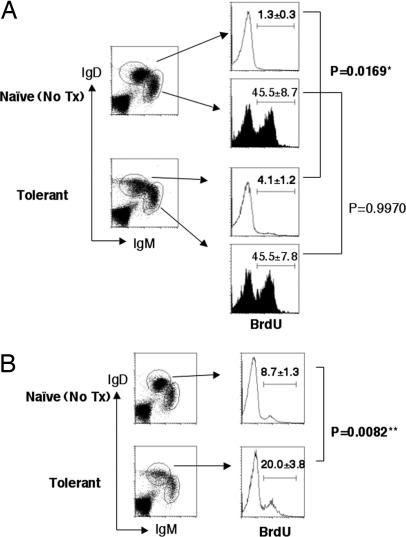

To further demonstrate that the loss of mature B cells was not because of the blocking of development from immature/transitional to mature B cells, we performed a BrdU labeling experiment. A short-term (3-day) labeling showed the same BrdU+ percentages (45.5%) in IgDlowIgMhigh immature B cells in both naive and tolerant mice (Fig. 5A). Only small percentages of IgDhighIgMlow mature B cells in naive and tolerant mice (1.3 and 4.1%, respectively) were labeled in this short-term treatment. A longer term (10-day) labeling clearly showed a significant increase in the percentage of BrdU+ mature B cells in tolerant mice (20.0%) compared with the same population in naive mice (8.7%) (P = 0.0082) (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that the turnover rate of mature B cells is higher in tolerant mice than in naive ones, whereas the turnover rates of the immature B cells are the same. From this, we conclude that the loss of mature B cells in the tolerant 3-83Igi mice is not because of developmental block but because of cell death at mature stage.

Fig. 5.

Mature B cells in tolerant mice have higher turnover rate than those in naive mice. Spleen cells were isolated from naive or tolerant 3-83Igi after 3 days (A) or 10 days (B) of BrdU labeling. Cells were stained with anti-IgM, anti-IgD, and anti-BrdU. Data are shown as average of BrdU+ percentages from each gated population ± SD (n = 3 /group). ∗, Statistically significant; ∗∗, very significant.

CD4 Depletion Also Resulted in Alloreactive B Cell Deletion After Transplant.

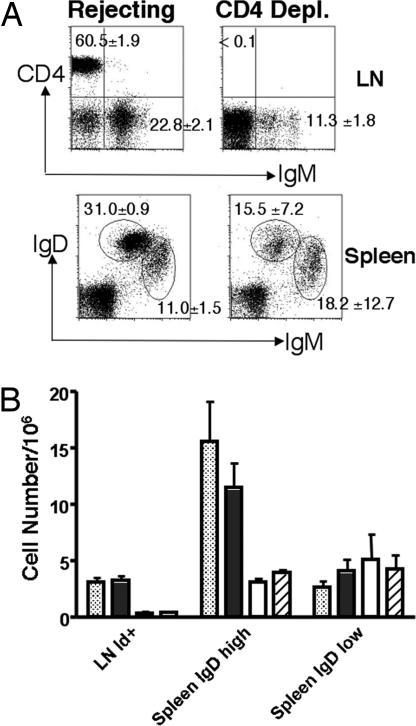

The interaction between CD40 on B cell and CD154 on T helper cells is crucial for B cells activation and differentiation, and this interaction is blocked by anti-CD154 (18). We hypothesize that the absence of this costimulation signal from T helper cells, in the presence of alloantigen, may be the cause of B cell death. We reasoned that, if this were the case, depletion of T helper cells should achieve the same effect on alloreactive B cells as anti-CD154. We treated 3-83 mice that received C57BL/6 hearts repeatedly with anti-CD4 antibody to deplete CD4+ T cells. One month later, cells were isolated from the lymph node and spleen of mice treated with anti-CD4. Controls were mice that received heart transplant but no anti-CD4 treatment. Complete depletion of CD4+ cells was confirmed by staining cells from lymph node using a different anti-CD4 antibody (Fig. 6A Upper). CD4 depletion resulted in significant reductions in the percentage of IgM+ B cells in the lymph node (P = 0.0018) and IgMlowIgDhigh mature B cells in the spleen (P = 0.0210). Again, there was no significant change in the percentage of IgMhighIgDlow immature B cells in the spleen (P = 0.3807) (Fig. 6A). Total cell numbers showed a same pattern of 3-83 B cells deletion in the anti-CD4-depleted and anti-CD154/DST-treated groups. We observed significant reduction in idiotype-positive B cells in the lymph node and IgDhigh mature cells in the spleen. In contrast, there was no reduction in the IgDlow immature population (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that the absence of T cell help may be the basis for the peripheral deletion of alloreactive B cells.

Fig. 6.

CD4 depletion led to 3-83 B cell deletion after allograft transplant. (A) 3-83Igi mice that received C57BL/6 hearts were treated with anti-CD4 antibody to deplete CD4+ cells. One month later, cells were isolated from the lymph nodes (LN) and spleen and stained with anti-CD4, anti-IgM, and anti-IgD antibodies. Data were shown as the average of CD4+ and IgM+ cell percentages from lymphoid gate in the lymph nodes (Upper) and mature (IgDhighIgMlow) or immature (IgDlowIgMhigh) B cell percentages from the lymphoid gate in the spleen (Lower) ± SD (n = 3 per group). (B) The average of total B cell numbers from naive (dotted bars), rejecting (filled bars), and tolerant (empty bars; treated with anti-CD154/DST) mice, and mice treated with anti-CD4 depletion (striped bars) (all 1 month after transplant) are shown ± SD (n ≥ 3 per group).

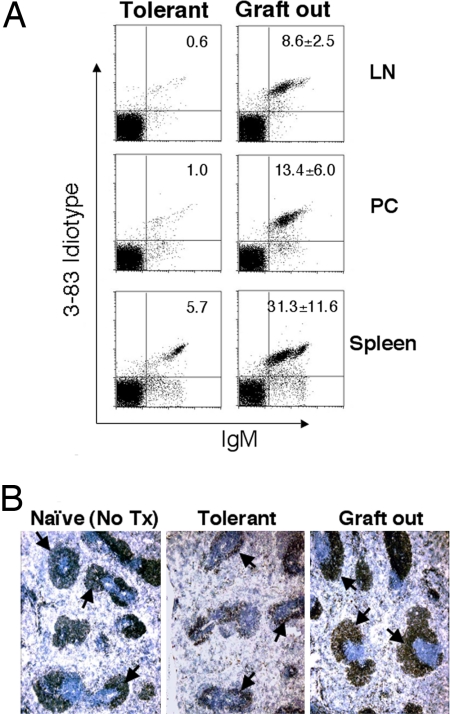

Removal of Allograft Led to Partial Recovery of 3-83 B Cells in Tolerant Mice.

Because 3-83 B cells are continually generated from the bone marrow, they must be continually deleted in the periphery. It has been recently reported that antigen binding is required for maintaining the inactive stage of anergic B cells (24). We therefore tested whether a continual deletion process also requires the presence of allograft. Six weeks after transplantation, heart grafts were surgically removed from the abdominal cavity of tolerant mice. Four weeks later, cells from lymph nodes, peritoneal cavity, and spleen were analyzed. A significant recovery of 3-83 B cells was observed, compared with a control tolerant mouse whose transplanted heart was not removed (Fig. 7A). The observation that B cell numbers did not fully recover to the level of naive or rejecting mice suggests that some alloantigen might still be present, even after graft removal, to induce B cell deletion. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the partial restoration in the size of B cell follicles in the spleen after graft removal (Fig. 7B). This observation suggests that antigen from the graft is required for maintaining the deletion of alloreactive B cells.

Fig. 7.

Removal of allograft led to partial recovery of 3-83 B cells in tolerant mice. (A) Heart grafts were surgically removed from the abdominal cavity of tolerant mice 6 weeks after transplant. Four weeks later, cells from lymph nodes (LN), peritoneal cavity (PC), and spleen were isolated and stained with anti-IgM and anti-Id antibodies. There were three mice in this experimental group, and data are shown as the average of Id+ B cell percentages from the lymphoid gate ± SD (Right). Staining from a control tolerant mouse that received transplant on the same day as the experimental group, but without graft removal, is shown on Left. (B) Spleen sections of naive or tolerant mice, and tolerant mice whose transplanted grafts were removed 4 weeks before killing, were stained with anti-Id antibody to reveal 3-83 B cells in follicles (dark brown; marked by arrows).

Discussion

Various strategies have been developed to induce B cell tolerance after transplant. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism has been shown to be able to achieve B cell tolerance through central deletion in the bone marrow (25). Infants receiving ABO-incompatible grafts developed donor-specific B cell tolerance through deletion (26), but it was not clear where or when the deletion occurred. In our current study, the use of 3-83Igi mice allowed us to demonstrate that the induction of transplant tolerance with anti-CD154/DST leads to the antigen-specific peripheral deletion of alloreactive B cells. This loss of 3-83 B cells was measured by anti-Id using 54.1 antibody as well as by Kb tetramer staining (data not shown). We also observed an increase of the percentage of Id-negative B cells in the spleen of tolerant mice. This is due mainly to the decrease of Id-positive B cells, because the total numbers of Id-negative spleen B cells remained the same between tolerant and naive 3-83Igi mice. At this time, we cannot rule out the possibility that receptor editing might also be involved after tolerance induction. Another concern is the use of 3-83Igi mice that have high frequency of alloreactive B cells.

It has been reported that self-reactive B cells can be deleted in the periphery. The targeted expression of Kb antigen in the liver resulted in normal development of B cells in the bone marrow, but they were deleted in the periphery (22). The fact that both immature and mature self-reactive B cells were eliminated suggests that deletion occurred at the immature stage, soon after B cells migrated out of the bone marrow and contacted self-antigen. In another report, the expression of Kk antigen (also recognized by 3-83 B cells) by the fetus resulted in the profound deletion of the immature 3-83 transgenic B cells and a partial loss of the mature 3-83 B cells (27). When the Kb antigen is expressed only in mouse trophoblast, it caused the deletion of bone marrow B cell subpopulation, including immature and transitional B cells, but not in the spleen (28). In contrast, in our transplant tolerant model, the deletion of alloreactive B cells induced by anti-CD154 therapy occurred only in the mature B cell subsets, and there was no loss of immature B cells.

It has previously been shown that mature self-reactive 3-83 B cells can be rapidly eliminated when they encounter self-antigen that is constitutively expressed throughout all tissues and when self-reactive T cell help is absent (29). The notion that T cell help can modulate B cell survival is supported by reports that anergic self-reactive B cells, which usually have a short life span, can be rescued if T cell help is provided (30). Here, we have extended these findings and demonstrated that alloreactive 3-83 B cells can be deleted on encountering peripheral antigen when treated with anti-CD154. This, together with the CD4 depletion experiment, suggests that the death of alloreactive B cells when contacting alloantigen is caused by the missing of T cell help.

It is puzzling that, in our experiments, we did not observe deletion of immature B cells, which are known to be highly susceptible to antigen-induced cell death (31, 32). One possibility could be that immature B cells did not contact the alloantigen. Only mature B cells circulate and therefore have a better chance of contacting the alloantigen in the blood or in the graft. It is also possible that only a low dose of alloantigen is present in the blood system and that these antigens are picked up by antigen-presenting cells and delivered to the B cell follicles, where mature B cells locate but immature B cells are not able to enter (33). Consistent with the notion that the level of antigen-mediated signaling determines the basis of B cell tolerance is the observation of the depletion of mature, but not immature, B cells when self-antigen is expressed at a low level (34). When the self-antigen was present at a high level, virtually all self-reactive B cells are eliminated, primarily or exclusively through receptor editing (35). In contrast, when tissue-specific self-antigen is sequestered by endothelium and basement membrane, no active B cell tolerance occurs (36).

Our results reveal that a short course of anti-CD154 treatment (days 0, 7, and 14) can result in long-term (>90 days) deletion. The half-life of anti-CD154 is reported to be ≈10 days (37). It is unlikely that, 46–76 days after the last anti-CD154 treatment, there are still sufficient antibodies to block the CD154–CD40 interaction between T and B cells. So how is the B cell tolerance maintained long after the anti-CD154 treatment? We know that persistence of the allograft is necessary to maintain B cell depletion. Additionally, the tolerant mice may have developed long-lasting regulatory mechanisms. Indeed, it has been reported that anti-CD154/DST treatment can invoke regulatory T cells, which are critical for the long-term survival of the allograft (14, 15). It is possible that such induced regulatory T cells suppress alloreactive helper T cell function. This possibility is supported by reports that CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells can suppress helper T cells (38, 39), resulting in inhibition of T-dependent B cell function. It has also been reported that regulatory T cells can directly suppress B cells independently of the suppression of helper T cells (40). Another possibility is that the tolerogenic dendritic cells, generated as a result of anti-CD154 treatment, can deliver a death signal directly to B cells. Further studies are ongoing to characterize the detailed mechanism of maintaining long-term peripheral B cell tolerance induced by costimulation blockade.

In summary, the sustained deletion of mature alloreactive B cells on persistent encounter with alloantigen in the periphery in the absence of T cell help illustrates the unique susceptibility of this subset of B cells, over the immature subset, in the transplantation tolerance setting. The reduction of the alloreactive B cell repertoire may facilitate the development of a more stringent state of immunoregulatory tolerance, similar to what has been suggested for alloreactive T cells (41). Finally, these observations emphasize the complexity of B cell tolerance mechanisms in the periphery, whereby a B cell-extrinsic mechanism of tolerance, namely the inhibition of T cell help, can manifest in a B cell-intrinsic mechanism of tolerance involving the depletion of mature alloreactive B cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The 3-83Igi mice on BALB/c background have been previously described (21) and were a generous gift from Dr. Roberta Pelanda (Department of Immunology, National Jewish Medical and Research Center and University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO). BALB/c mice were purchased from National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD), and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). KbDb knockout mice (on C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Dr. Chyung-Ru Wang (Department of Pathology, University of Chicago). All mice were maintained in pathogen-free conditions in the animal facilities of University of Chicago following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Surgical Procedures.

Cardiac allografts were transplanted into the abdominal cavity by end-to-side anastomosing of the aorta and pulmonary artery of the graft to the recipient's aorta and vena cava, respectively. Graft removal was performed 6 weeks after the initial transplant.

Tolerance Induction.

Mice received ≈20 million total donor spleen cells on the day of transplant. In addition, they were treated with three doses of 1 mg of anti-CD154 (MR1) (i.v. on day 0; i.p. on days 7 and 14).

Analysis of Donor-Reactive Alloantibody Titers.

Donor-reactive antibodies were determined by flow cytometry. Sera (1:10 diluted) were incubated with C57BL/6 lymph node cells for 1 h. Cells were washed and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgM-phycoerythrin, anti-IgG-FITC (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL), and anti-CD19-peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5 (1D3) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). The mean channel fluorescence of the CD19− population from the lymphoid gate was determined by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry.

Cells were prepared from lymph node, peritoneal cavity, spleen, and bone marrow at times indicated, and passed through 48-μm nylon mesh (Small Parts, Miami, FL). Antibodies used for staining were as follows: anti-Id 54.1 (23), which recognizes 3-83 B cells expressing the transgene (conjugated to FITC by the core facility at University of Chicago); goat anti-mouse IgM-phycoerythrin, anti-IgM-allophycocyanin (1B4B1) (Southern Biotechnology); and anti-B220-phycoerythrin (RA3-6B2), anti-IgD-FITC (11-26c.2a), and anti-CD21-FITC (7G6) (BD Pharmingen). Dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) except when 7-AAD (BD Pharmingen) was used to analyze the percentage of dead cells in the spleen. Stained cells were analyzed by using FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA).

Immunohistochemistry.

Spleens and heart grafts were removed, embedded with OCT (Tissue-Tek; Miles, Elkhart, IN), and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue sections (6 μm) were stained with rat anti-IgM (R4-22) (BD Pharmingen) or 54.1 (anti-Id). The sections were then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (BD Pharmingen), followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). Immunostainings were developed with the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

BrdU Labeling.

Naive or tolerant 3-83Igi mice (60 days after transplant) were treated with BrdU (1 mg per mouse each day, i.p.) for 3 days (short-term labeling) or 10 days (long-term labeling). Spleen cells were isolated and analyzed for BrdU labeling by using the BrdU flow kit (BD Pharmingen).

CD4 in Vivo Depletion.

A total of 0.2 mg of anti-CD4 (GK1.5) was given to recipient mice (i.v.) on days −1 and 0 of transplant. The mice were then given the same dose of antibody weekly for a month, whereupon they were killed for analysis.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by t test using the Prism program (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roberta Pelanda for providing the 3-83Igi mice, Dr. Chyung-Ru Wang for providing the KbDb knockout mice, Ms. Ting-ting Zhou for her help in purifying the anti-CD154 antibody, and Drs. Yang-xin Fu and Ian Boussy for critical discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 2R56AI043631-07A2 (to A.S.C.).

Abbreviations

- DST

donor-specific transfusion

- Id

idiotype

- 7-AAD

7-aminoactinomycin D.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Colvin RB, Smith RN. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:807–817. doi: 10.1038/nri1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespo M, Pascual M, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Mauiyyedi S, Collins AB, Fitzpatrick D, Farrell ML, Williams WW, Delmonico FL, Cosimi AB, et al. Transplantation. 2001;71:652–658. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauiyyedi S, Pelle PD, Saidman S, Collins AB, Pascual M, Tolkoff-Rubin NE, Williams WW, Cosimi AA, Schneeberger EE, Colvin RB. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:574–582. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V123574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snanoudj R, Beaudreuil S, Arzouk N, de Preneuf H, Durrbach A, Charpentier B. Transplantation. 2005;79:S33–S36. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153298.48353.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngo VN, Cornall RJ, Cyster JG. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1649–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasowska BA, Qian Z, Cangello DL, Behrens E, Van Tran K, Layton J, Sanfilippo F, Baldwin WM., III Transplantation. 2001;71:727–736. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markees TG, Phillips NE, Noelle RJ, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Transplantation. 1997;64:329–335. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707270-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wekerle T, Kurtz J, Ito H, Ronquillo JV, Dong V, Zhao G, Shaffer J, Sayegh MH, Sykes M. Nat Med. 2000;6:464–469. doi: 10.1038/74731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camirand G, Caron NJ, Turgeon NA, Rossini AA, Tremblay JP. Transplantation. 2002;73:453–461. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tung TH, Mackinnon SE, Mohanakumar T. Transplantation. 2003;75:644–650. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000053756.90975.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Gool SW, Vermeiren J, Rafiq K, Lorr K, de Boer M, Ceuppens JL. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2367–2375. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2367::AID-IMMU2367>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwakoshi NN, Mordes JP, Markees TG, Phillips NE, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. J Immunol. 2000;164:512–521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor PA, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1311–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, Hidalgo A, Garin A, Tacke F, Angeli V, Li Y, Boros P, Ding Y, et al. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:652–662. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker DC, Greiner DL, Phillips NE, Appel MC, Steele AW, Durie FH, Noelle RJ, Mordes JP, Rossini AA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9560–9564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quezada SA, Fuller B, Jarvinen LZ, Gonzalez M, Blazar BR, Rudensky AY, Strom TB, Noelle RJ. Blood. 2003;102:1920–1926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noelle RJ. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76:S203–S207. doi: 10.1016/s0090-1229(95)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin D, Ma L, Varghese A, Shen J, Chong AS. J Immunol. 2002;168:5352–5358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelanda R, Schwers S, Sonoda E, Torres RM, Nemazee D, Rajewsky K. Immunity. 1997;7:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halverson R, Torres RM, Pelanda R. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:645–650. doi: 10.1038/ni1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell DM, Dembic Z, Morahan G, Miller JF, Burki K, Nemazee D. Nature. 1991;354:308–311. doi: 10.1038/354308a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemazee DA, Burki K. Nature. 1989;337:562–566. doi: 10.1038/337562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauld SB, Benschop RJ, Merrell KT, Cambier JC. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/ni1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohdan H, Yang YG, Shimizu A, Swenson KG, Sykes M. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:281–290. doi: 10.1172/JCI6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan X, Ang A, Pollock-Barziv SM, Dipchand AI, Ruiz P, Wilson G, Platt JL, West LJ. Nat Med. 2004;10:1227–1233. doi: 10.1038/nm1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ait-Azzouzene D, Gendron MC, Houdayer M, Langkopf A, Burki K, Nemazee D, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C. J Immunol. 1998;161:2677–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ait-Azzouzene D, Caucheteux S, Tchang F, Wantyghem J, Moutier R, Langkopf A, Gendron MC, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:337–344. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam KP, Rajewsky K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13171–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulcher DA, Lyons AB, Korn SL, Cook MC, Koleda C, Parish C, Fazekas de St Groth B, Basten A. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2313–2328. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carsetti R, Kohler G, Lamers MC. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2129–2140. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monroe JG. J Immunol. 1996;156:2657–2660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loder F, Mutschler B, Ray RJ, Paige CJ, Sideras P, Torres R, Lamers MC, Carsetti R. J Exp Med. 1999;190:75–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ait-Azzouzene D, Verkoczy L, Duong B, Skog P, Gavin AL, Nemazee D. J Immunol. 2006;176:939–948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ait-Azzouzene D, Verkoczy L, Peters J, Gavin A, Skog P, Vela JL, Nemazee D. J Exp Med. 2005;201:817–828. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akkaraju S, Canaan K, Goodnow CC. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2005–2012. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson T, Markees TG, Wicker LS, Serreze DV, Peterson LB, Mordes JP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Diabetes. 2003;52:321–326. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim HW, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1640–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI22325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fields ML, Hondowicz BD, Metzgar MH, Nish SA, Wharton GN, Picca CC, Caton AJ, Erikson J. J Immunol. 2005;175:4255–4264. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim HW, Hillsamer P, Banham AH, Kim CH. J Immunol. 2005;175:4180–4183. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells AD, Li XC, Li Y, Walsh MC, Zheng XX, Wu Z, Nunez G, Tang A, Sayegh M, Hancock WW, et al. Nat Med. 1999;5:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]