Summary

In addition to affecting respiration and vascular tone, deviations from normal CO2 alter pH, consciousness, and seizure propensity. Outside the brainstem, however, the mechanisms by which CO2 levels modify neuronal function are unknown. In the hippocampal slice preparation, increasing CO2, and thus decreasing pH, increased the extracellular concentration of the endogenous neuromodulator adenosine and inhibited excitatory synaptic transmission. These effects involve adenosine A1 and ATP receptors and depend on decreased extracellular pH. In contrast, decreasing CO2 levels reduced extracellular adenosine concentration and increased neuronal excitability via adenosine A1 receptors, ATP receptors, and ecto-ATPase. Based on these studies, we propose that CO2-induced changes in neuronal function arise from a pH-dependent modulation of adenosine and ATP levels. These findings demonstrate a mechanism for the bidirectional effects of CO2 on neuronal excitability in the forebrain.

Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels constantly regulate respiration rate and blood flow, and in turn these physiological processes control CO2 levels (Feldman et al., 2003; Richerson, 2004). Both clinical and experimental evidence indicates that changes in CO2 have additional major effects on neuronal excitability and seizure propensity in susceptible individuals (Balestrino and Somjen, 1988; Brian, 1998; Guaranha et al., 2005; Mulkey et al., 2004). Recent studies have shown that adenosine triphosphate (ATP) acts as a chemosensory molecule in the medulla to mediate CO2-induced changes in respiration (Gourine et al., 2005). Other studies suggest that serotonergic neurons of the medulla transduce alterations in CO2 into changes in vascular tone (Bradley et al., 2002; Severson et al., 2003). In cortical structures, CO2 affects neuronal excitability, an empirical but unexplained finding long exploited by physicians. Thus, mechanisms underlying CO2-induced changes in cortical function are also of great interest because CO2 has a profound influence on seizure propensity and vigilance state. However, the physiological mechanism of CO2-induced changes has yet to be described.

Decreasing CO2 (hypocapnia) increases neuronal excitability in the hippocampus and is used diagnostically to induce seizures (Achenbach-Ng et al., 1994; Bao et al., 2000; Guaranha et al., 2005; Miley and Forster, 1977; Wirrell et al., 1996) and therapeutically to prolong seizures during electroconvulsive therapy (Datto et al., 2002). Conversely, increasing CO2 levels (hypercapnia) decreases hippocampal neuronal excitability (Balestrino and Somjen, 1988), causes sedation, and has a long history as an anesthetic (Capps, 1968). Although the neurological effects of changing CO2 partial pressure (PCO2 ) remained mechanistically enigmatic, CO2 levels influence tissue pH, which has also been linked to neuronal excitability (Aram and Lodge, 1987; Balestrino and Somjen, 1988; Chesler, 2003; Lee et al., 1996). Based on previous studies (Fujiwara et al., 1992; Irwin et al., 1994; Masino and Dunwiddie, 1999), we suspected that tissue acidification could cause an increase in extracellular adenosine, a neuromodulator with a predominantly inhibitory influence in the hippocampus. Adenosine is a metabolite of ATP, and both of these purines influence synaptic transmission. Therefore, we hypothesized that CO2-induced changes in pH may alter neuronal excitability by altering extracellular adenosine and ATP concentrations.

Adenosine acts at four G protein-coupled receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, A3) (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001) and acts principally at the adenosine A1 receptor in the hippocampus (Johansson et al., 2001; van Calker et al., 1979) to provide tonic inhibition of glutamate release and hyperpolarize neurons. The inhibitory actions of adenosine are considered important in terminating seizures (Boison et al., 2002; Malva et al., 2003), maintaining postictal depression (Etherington and Frenguelli, 2004), and restoring metabolic equilibrium following seizure activity (Dunwiddie, 1999). Adenosine reaches the extracellular space directly via the nucleoside transporter (Gu et al., 1995) and indirectly when ecto-nucleotidases convert extracellular ATP into adenosine (Cunha et al., 1998; Dunwiddie et al., 1997; Zimmermann, 2000).

Extracellular ATP affects neurotransmission either directly, via ionotropic (P2X) and metabotropic (P2Y) receptors (Mendoza-Fernandez et al., 2000; Pankratov et al., 1999; Rodrigues et al., 2005), or indirectly via its subsequent extracellular metabolism to adenosine (Cunha et al., 1998; Dunwiddie et al., 1997). ATP receptors have been shown to increase excitatory inputs onto inhibitory interneurons (Khakh et al., 2003), mediate a portion of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in hippocampal areas CA1 (Pankratov et al., 1998) and CA3 (Mori et al., 2001), and affect long-term potentiation (Almeida et al., 2003; Pankratov et al., 2002). The specific role and distribution of P2 receptors is still being elucidated (Burnstock, 2004; Khakh, 2001; Pankratov et al., 1998), but it is known that ATP receptors can significantly modulate transmitter release in the hippocampus (Pankratov et al., 1998; Rodrigues et al., 2005; Sperlagh et al., 2002).

To determine whether the purines adenosine and ATP are responsible for the profound effects of CO2 on neuronal function in the hippocampus, we used a combination of electrophysiology, an enzymatic adenosine biosensor (Dale, 1998; Dale et al., 2000), and two-photon pH imaging, to investigate the relationship between changes in brain CO2 levels and altered neuronal excitability. We show that CO2 influences cortical excitability via an interaction between extracellular pH, ATP-metabolizing enzymes and receptors for ATP and adenosine. These changes are responsible for the profound neuronal effects of CO2 and suggest mechanisms to explain the global neurological effects of altered CO2, such as seizures and sedation.

Results

CO2 Alters Synaptic Transmission

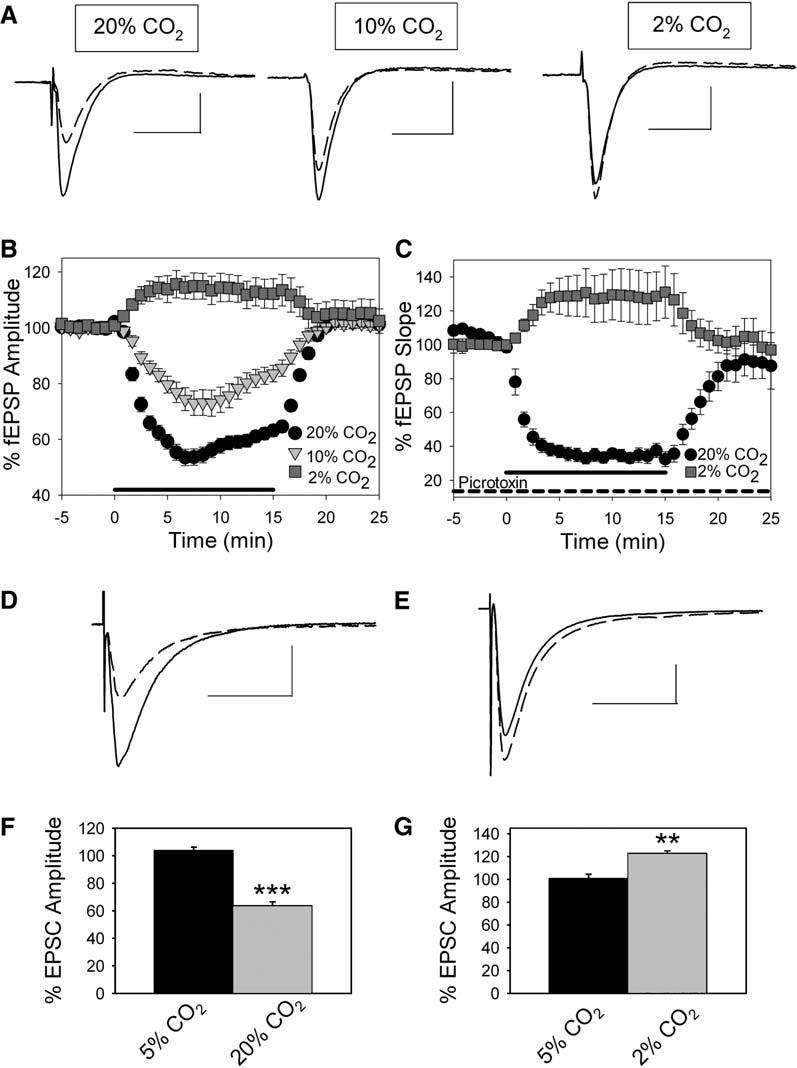

To explore the relationship between CO2, adenosine, and neuronal excitability, we first manipulated the levels of CO2 and oxygen in our artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) while monitoring CA1 field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs). Under control conditions, aCSF contained 5% CO2 and 26 mM sodium bicarbonate and had a pH of 7.4 ± 0.1 (n = 25). Exposing slices to 15 min of hypercapnia (CO2 = 20%; aCSF pH = 6.7 ± 0.1) inhibited fEPSP amplitude by 45.8% ± 3.7% (Figure 1A, left, and Figure 1B; n = 33). This effect was reversible upon return to control aCSF (Figure 1B). To address the concentration dependence of this effect, we tested aCSF containing 10% CO2 (aCSF pH = 7.1 ± 0.1) on fEPSP amplitude. This more modest level of hypercapnia decreased fEPSP amplitude by 27.3% ± 4.5% (Figure 1A, center, and Figure 1B; n = 11), significantly less than when exposed to 20% CO2 buffer (p < 0.01, analysis of variance [ANOVA], Fisher protected least squared difference [PLSD] test). To test if the effects of CO2 were bidirectional, we exposed slices to hypocapnia (CO2 = 2%; aCSF pH = 7.7 ± 0.1). Upon exposure to 2% CO2, fEPSP amplitude increased by 18.8% ± 3.1% (Figure 1A, right, and Figure 1B; n = 14).

Figure 1.

Changes in CO2 Levels Alter Synaptic Transmission and Adenosine Levels in Area CA1

(A) Field EPSPs averaged from a single experiment. Control (solid) and 20% CO2, 10% CO2, and 2% CO2 exposure (dashed). Scale bars, 25 ms, 0.5 mV. (B) Time course of fEPSP inhibition when aCSF CO2 level was changed from 5% (control) to hypercapnia (20% CO2, circles, n = 23; 10% CO2, triangles, n = 11) or hypocapnia (2% CO2, squares, n = 11) for 15 min (mean ± SEM). Thick line on x axis represents CO2 manipulation. (C) Time course of fEPSP inhibition during GABAA receptor blockade with 100 μM picrotoxin when aCSF CO2 level was changed from 5% (control) to hypercapnia (20% CO2, circles, n = 8) or hypocapnia (2% CO2, squares, n = 7) for 15 min (mean ± SEM). Thick line on x axis represents the timing of CO2 manipulation. (D) Excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) from a CA1 pyramidal cell under control conditions (5% CO2; solid line; average of five EPSCs) and during exposure to 20% CO2 (dashed line; average of five EPSCs). Scale bars, 25 ms, 200 pA. (E) Excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) from a CA1 pyramidal cell under control conditions (5% CO2; solid line; average of five EPSCs) and during exposure to 2% CO2 (dashed line; average of five EPSCs). Scale bars, 25 ms, 200 pA. (F) Average EPSC during 5% CO2 (black bar; n = 5) and during exposure to 20% CO2 (gray bar; n = 5; ***p < 0.001, Student's t test). (G) Average EPSC amplitude during 5% CO2 (black bar; n = 5) and during exposure to 2% CO2 (gray bar; n = 5; **p < 0.01, Student's t test). Error bars indicate standard error.

The Effects of CO2 on Synaptic Transmission Are Not Mediated by Changes in GABAergic Transmission

To isolate the role of CO2 in altering excitatory neurotransmission we repeated these experiments in the presence of 100 μM picrotoxin, an antagonist of inhibitory GABAA receptors. During GABAA receptor blockade, exposure to hypercapnia (20% CO2) caused a 67.1% ± 3.1% inhibition of fEPSP slope, significantly more than that induced when GABAA receptors are active (Figure 1C; Figure S1A in the Supplemental Data available with this article online; n = 8; p < 0.0001, Student's t test). When we exposed slices to hypocapnia (2% CO2) during GABAA receptor blockade, fEPSP slope increased by 33.1% ± 11.6% (Figure 1A; Figure S1B; n = 7; p > 0.05, Student's test) similar to the effects of hypocapnia under control conditions. Because the inhibitory effects of hypercapnia and the excitatory effects of hypocapnia persist when GABAA receptors are blocked, the effects of hypercapnia and hypocapnia are not due to changes in GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition.

Whole-Cell Recordings Confirm Changes in Excitability Caused by CO2

We next examined the effects of altered CO2 levels on CA1 pyramidal cell postsynaptic currents using whole-cell recording. When recording from CA1 pyramidal cells, we found that hypercapnia (20% CO2) decreased excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) evoked at −60 mV by 36.4% ± 2.9% (Figures 1D and 1F; n = 5; p < 0.001 compared to control EPSC amplitude, Student's t test). When CO2 levels were decreased to 2% (hypocapnia), EPSC amplitude evoked at −60 mV increased by 22.6% ± 2.4% (Figures 1E and 1G; n = 5; p < 0.01 compared to control EPSC amplitude, Student's t test). Interestingly, inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) evoked at 0 mV decreased during exposure to hypercapnia by 28.1% ± 2.6%, further ruling out increased GABAergic transmission as the mechanism of hypercapnia-induced inhibition (Figures S2A and S2B; n = 5; p < 0.001 compared to control IPSC amplitude, Student's t test).

Extracellular Adenosine Levels Change during Hypercapnia and Hypocapnia

We recorded extracellular adenosine levels from CA1 using an enzymatic adenosine sensor (Dale, 1998; Dale et al., 2000). When we exposed slices to hypercapnia (CO2 = 20%), extracellular adenosine levels rose by 0.72 ± 0.13 μM(Figure 2A; n = 23). To address the concentration dependence of this effect, we also examined the effects of raising aCSF CO2 levels to 10%. Under these conditions, extracellular adenosine levels rose by 0.29 ± 0.07 μM(Figure 2A; n = 10). We tested if the effects of CO2 were bidirectional by exposing slices to 2% CO2 (hypocapnia). When we switched slices from control aCSF to hypocapnic aCSF, extracellular adenosine levels decreased by 0.41 ± 0.15 μM(Figure 2A; n = 8).

Figure 2.

Changes in CO2 Levels Alter Extracellular Adenosine Concentration

(A) Average change in extracellular adenosine levels caused by hypercapnia (20% CO2, n = 23, ***p < 0.005 compared to baseline sensor measurement, Student's paired t test; and 10% CO2, n = 10, *p < 0.05 compared to baseline sensor measurement, Student's paired t test) and hypocapnia (2% CO2, n = 8, *p < 0.05 compared to baseline sensor measurement, Student's paired t test, all groups are significantly different, p < 0.01, ANOVA). (B) Average change in extracellular adenosine levels during GABAA receptor blockade caused by hypercapnia (20% CO2, n = 5, ***p < 0.005 compared to baseline sensor measurement, Student's paired t test) and hypocapnia (2% CO2,n = 7, ***p < 0.005 compared to baseline sensor measurement, Student's paired t test). Error bars indicate standard error.

If the CO2-induced changes in adenosine concentrations that we measured with the adenosine sensor were responsible for the CO2-induced changes in synaptic transmission, this would indicate that submicro-molar adenosine concentrations profoundly depress synaptic activity. Although this is consistent with the potency of adenosine at adenosine receptors (Dunwiddie and Diao, 1994), adenosine uptake may influence the adenosine sensor signal and result in an underestimation of the concentration of synaptic adenosine evoked by changes in PCO2. To test whether adenosine uptake altered our sensor signals, we blocked the nucleoside transporter with dipyridamole (10 μM) and measured the change in extracellular adenosine caused by 20% CO2. Blockade of the transporter caused a steady decrease in fEPSP amplitude that reached 35.4% ± 3.1% inhibition (n = 8) and increased extracellular adenosine levels by 1.49 ± 0.41 μM (n = 6) after 30 min of exposure to dipyridamole. When the transporter was blocked, 20% CO2 increased extracellular adenosine significantly more than under control conditions (Figure S2A; Δ[adenosine] = 1.20 ± 0.13 μM; p < 0.05, Student's t test; n = 4) and depressed the fEPSP by 54.9% ± 5.7% (Figure S2B). Furthermore, when a similar concentration of exogenous adenosine (1.5 μM) was applied during inhibition of the nucleoside transporter, fEPSPs were inhibited by 54.8% ± 5.4% (Figure S2C; n = 4). These results are consistent with previous studies (Dunwiddie and Diao, 1994; Gadalla et al., 2004; Pearson et al., 2001) and underscore the efficient removal of adenosine by nucleoside transport.

GABAA Receptor Blockade Does Not Alter CO2-Induced Changes in Adenosine

During GABAA receptor blockade with picrotoxin, changes in extracellular adenosine levels were consistent with those seen without GABAA receptors blocked. When GABAA receptors were blocked, hypercapnia (20% CO2) increased extracellular adenosine levels (Figure 2B; Δ [adenosine] = 0.32±0.02; n = 5), and hypocapnia decreased extracellular adenosine levels (Figure 2B; Δ [adenosine] = −0.45±0.13; n = 7). Hypercapnia- and hypocapnia-induced changes in adenosine were not significantly altered by GABAA receptor blockade (p>0.05, Student's t test for both CO2 manipulations).

Effects of Hypercapnia Are Not Due to Hypoxia

Hypoxia and ischemia are known to cause adenosine release and inhibit synaptic transmission. In our hypercapnia experiments, CO2 levels are increased by removing a portion of oxygen from the gas mixture. This results in reduced oxygen conditions relative to control (control oxygen content = 95%; hypercapnic oxygen content = 80%). To address whether this lowered oxygen content was responsible for any of the effects of hypercapnia, we exposed slices to a buffer with a lowered oxygen level and a control CO2 level (low-oxygen control buffer = 80% O2, 15% N2, and 5% CO2). These control experiments revealed that the effects of elevated CO2 were not attributable to hypoxia, since the low-oxygen control buffer had no effect on synaptic transmission (Figures 3A and 3B; n = 7; p < 0.001 compared to effects of 20% CO2, Student's t test). Similarly, increases in extracellular adenosine were not due to hypoxia, as the low-oxygen control buffer did not increase adenosine levels (Figure 3C; Δ [adenosine] = −0.15 ± 0.7 μM; n = 5; p > 0.05 compared to baseline sensor reading, p < 0.001 compared to effects of 20% CO2, Student's t test).

Figure 3.

Decreased O2 Levels Do Not Account for Changes Seen during Hypercapnia (A) Inhibition of fEPSP amplitude by hypercapnic buffer was not due to decreased oxygen (n = 7; ***p < 0.001, Student's t test). (B) Average fEPSPs from control (solid line; average of five fEPSPs) and decreased oxygen buffer (dashed line; average of five fEPSPs). Scale bars, 25 ms, 0.5 mV. (C) Adenosine release caused by hypercapnic buffer was not caused by decreased oxygen (n = 5; ***p < 0.001, Student's t test). Error bars indicate standard error.

pH Dependence of CO2's Effects on Excitability and Adenosine Release

To address the pH dependence of fEPSP inhibition and adenosine release caused by changes in CO2, we performed two-photon imaging of CA1 pyramidal cells (Figure 4A, inset) from hippocampal slices loaded with BCECF-AM, a pH-sensitive dye that exhibits a decrease in fluorescence upon a decrease in pHi. In control aCSF, CA1 pyramidal cells had a pHi of 7.4 ± 0.1 (n = 5). When we exposed slices to 10% CO2, pHi dropped to 7.0 ± 0.3 (n = 6), and pHi dropped further to 6.7 ± 0.4 when CO2 was increased to 20% (n = 6). Hypocapnia (2% CO2) caused a positive pH shift to 7.7 ± 0.1 (Figures 4A and 4B; n = 8).

Figure 4.

Changes in Adenosine and Excitability Correlate with Changes in Buffer pH and Are pH Dependent

(A) fEPSPs are plotted versus calculated pHi (R2 = 0.758). Inset: CA1 pyramidal cell loaded with BCECF-AM dye (black circle = 20% CO2, n = 6 for pHi measurement, n = 23 for fEPSP measurement; red circle = 10% CO2, n = 6 for pHi measurement, n = 13 for fEPSP measurement; yellow triangle = 20 mM propionic acid, n = 4 for pHi measurement, n = 5 for fEPSP measurement; green triangle = isohydric hypercapnia, n = 7 for pHi measurement, n = 7 for fEPSP measurement; blue square = 2% CO2, n = 8 for pHi measurement, n = 8 for fEPSP measurement). (B) Changes in extracellular adenosine are plotted versus calculated pHi (R2 = 0.848) (black circle = 20% CO2, n = 23 for adenosine measurement; red circle = 10% CO2, n = 13 for adenosine measurement; yellow triangle = 20 mM propionic acid, n = 5 for adenosine measurement; green triangle = isohydric hypercapnia, n = 7 for adenosine measurement; blue square = 2% CO2, n = 8 for adenosine measurement). (C) fEPSPs are plotted versus buffer pH (R2 = 0.992). (D) Changes in extra-cellular adenosine are plotted versus buffer pH (R2 = 0.996). (E) Inhibition due to 10% CO2 requires changes in buffer pH. Isohydric hypercapnia significantly attenuates the inhibition caused by 10% CO2 (n = 7; **p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Intracellular acidification alone (propionic acid exposure) causes significantly less inhibition than 10% CO2 (n = 5; ***p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). (F) Increased extracellular adenosine caused by 10% CO2 requires changes in pHe. Isohydric hypercapnia completely blocks the adenosine release caused by 10% CO2 (n = 7; **p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Intracellular acidification via propionic acid exposure was not sufficient to cause adenosine release (n = 5; ***p < 0.001 compared to 10% CO2, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Error bars indicate standard error.

To determine whether the changes in pH induced by hyper- and hypocapnic solutions were necessary for the effects on synaptic transmission, we subjected the slices to isohydric hypercapnia using an aCSF solution with additional buffering capacity (52 mM sodium bicarbonate) that has a pH similar to control despite increased CO2 (10% CO2; pH = 7.4 ± 0.1; n = 5). Isohydric hypercapnia induced only an 8.8% ± 2.9% decrease in BCECF fluorescence, significantly less than that induced during 10% hypercapnia (28.4% ± 5.3%; p < 0.01, Fisher PLSD), and pHi remained unchanged at 7.4 ± 0.1 (Figures 4A and 4B; n = 7) when we exposed slices to isohydric hypercapnia. This demonstrated that isohydric hypercapnia significantly attenuated CO2-induced pHi changes caused by 10% CO2. Accordingly, under these conditions fEPSP inhibition was significantly reduced compared to 10% CO2 (Figure 4E; n = 7; p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD), and adenosine release was significantly attenuated (Figure 4F; n = 7; p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). This indicates that hypercapnia-induced adenosine release and inhibition of fEPSPs are pH dependent.

To establish whether intracellular or extracellular pH changes were important in modulating adenosine release, we used 20 mM propionic acid, a weak organic acid, to decrease pHi while keeping aCSF buffer pH constant (Karuri et al., 1993). Propionic acid decreased BCECF fluorescence by 19.87% ± 2.88% (n = 5) and lowered pHi to 7.1 ± 0.1 (Figures 4A and 4B; n = 4), similar to the intracellular acidification that occurs with 10% CO2, even though the pH of the perfusate was similar to control values (7.4 ± 0.1; n = 5). Under these conditions, we observed less fEPSP inhibition and less adenosine release compared to 10% CO2, which produced similar changes in pHi (Figure 4E, n = 5, p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD and Figure 4F, n = 5, p < 0.01, n = 7, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD, respectively).

Furthermore, we examined the relationship between pHi and buffer pH (taken to be similar to pHe) and changes in fEPSPs and extracellular adenosine levels. Buffer pH showed a stronger correlation to both the inhibition of fEPSPs (pHi: R2 = 0.783; buffer pH: R2 = 0.992; Figures 4A and 4C) and changes in extracellular adenosine levels (pHi: R2 = 0.848; buffer pH: R2 = 0.996; Figures 4C and 4D). These data show that decreasing pHi alone is not sufficient, and changes in pHe are more likely to be the major determinant in the effects of CO2 on excitatory synaptic transmission and extracellular adenosine. We also confirmed these results by altering pH via changes in bicarbonate levels (Figure S3) and saw changes in excitability and adenosine levels consistent with those caused by altering pH via CO2.

Adenosine A1 and ATP Receptors Contribute to the Inhibitory Effects of Hypercapnia

To test the relationship between CO2- and pH-induced changes in adenosine concentration and fEPSP changes, we blocked adenosine A1 receptors with 1,3-Dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX; 100 nM) prior to increasing the CO2 content of the buffer. Application of DPCPX increased fEPSP amplitude by 26.7% ± 4.2% (n = 23; data not shown) consistent with previous studies (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001). Blockade of adenosine A1 receptors significantly decreased the inhibition caused by both 20% CO2 (27.3% ± 2.2% inhibition; Figure 5A; n = 8; p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD) and 10% CO2 (7.1 ± 1.7 inhibition; n = 5; p < 0.05, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD; data not shown) 10–15 min after CO2 exposure. This indicates that adenosine acts at the A1 receptor during hypercapnia to inhibit synaptic transmission.

Figure 5.

Adenosine A1 and ATP Receptors Mediate the Effects of Altered CO2 Levels

(A) Average inhibition of fEPSPs during 20% CO2 exposure (n = 33), 20% CO2 after DPCPX pretreatment (n = 8), 20% CO2 after P-PADS pretreatment (n = 3), and 20% CO2 after combined DPCPX and PPADS pretreatment (n = 8). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001, all compared to 20% hypercapnia, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD. (B) Average excitation of fEPSPs during 2% CO2 exposure (n = 14), 2% CO2 after DPCPX pretreatment (n = 6), 2% CO2 after PPADS pretreatment (n = 8), and 2% CO2 after combined DPCPX and P-PADS pretreatment (n = 13). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001, all compared to 2% hypocapnia, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD. Error bars indicate standard error.

Since DPCPX was unable to prevent fully the depression of the fEPSP caused by hypercapnia (20% CO2), we tested whether the major metabolic source of adenosine, ATP, might play a role. To test the role of ATP in mediating the effects of hypercapnia, we blocked ATP receptors (both P2X and P2Y subtypes) with 4-[[4-Formyl-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-3-[(phosphonooxy)methyl]-2-pyridinyl]azo]-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid (P-PADS; 20 μM). Blockade of ATP receptors alone had no effect on fEPSPs (2.7% ± 1.6% increase in fEPSP amplitude; n = 19; data not shown). When ATP receptors were blocked with P-PADS, however, hypercapnia inhibited fEPSPs by 16% ± 2.5% 10–15 min after CO2 exposure, significantly less than under control conditions (Figure 5A; n = 3; p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). When adenosine A1 and ATP receptors were both blocked, 20% CO2 caused no inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission after 10–15 min (4.0% ± 5.7% excitation; Figure 5A; n = 8; p < 0.0001).

Adenosine A1 and ATP Receptors Contribute to the Excitatory Effects of Hypocapnia

Based on our findings for hypercapnia, we suspected that similar mechanisms might underlie the mechanisms of hypocapnic changes in excitability. Blockade of adenosine A1 receptors with DPCPX (n = 5) occluded the excitation caused by 2% CO2 (7.9% ± 2.4% excitation; Figure 5B; n = 6; p < 0.05, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Similarly, antagonism of ATP receptors with P-PADS also prevented the excitation caused by hypocapnia (5.1% ± 2.1% excitation; Figure 5B; n = 8; p < 0.001). When ATP receptors and adenosine A1 receptors antagonists were coapplied, 2% CO2 had negligible effects on fEPSPs (4.1% ± 1.6% excitation; Figure 5B; n = 8; p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Results were similar for all conditions tested when another ATP receptor antagonist, suramin (50 μM) was used (data not shown).

Hypocapnia Increases Excitability and Decreases Adenosine Levels via Ecto-ATPase

Because the effects of hypercapnia and hypocapnia were mediated by both adenosine and ATP receptors, we examined the role of ecto-ATPase, an extracellular enzyme that breaks ATP down into ADP. Ecto-ATPase is known to be pH sensitive (Nagy et al., 1986; Ziganshin et al., 1994), and inhibiting ecto-ATPase with 6-N,N-Diethyl-β-γ-dibromomethylene-D-adenosine-5-triphosphate (ARL-67156; 100 μM) decreased extracellular adenosine levels by 0.44 ± 0.14 μM (Figure 6B; n = 11), suggesting that at least a portion of tonic extracellular adenosine comes from extracellular degradation of ATP. ARL-67156 is an ATP analog, however, and therefore has effects at other purinergic receptors (Drakulich et al., 2004). Inhibition of ecto-ATPase with ARL-67156 had a small effect on hippocampal excitability under control conditions (4.1% ± 1.6% increase in fEPSP amplitude; n = 23; data not shown) presumably due to these other, nonspecific effects of ARL-67156.

Figure 6.

The Effects of Hypocapnia Are Mediated by Ecto-ATPase, Adenosine A1 Receptors, and ATP Receptors

(A) Average increase in fEPSP amplitude during 2% CO2 exposure (n = 14), 2% CO2 after ARL-67156 pretreatment (n = 10), and 2% CO2 after combined ARL-67156 and P-PADS pretreatment (n = 5, **p < 0.01 compared to 2% hypocapnia, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). (B) When ARL-67156 was applied to the slice adenosine levels decreased and the decrease in extracellular adenosine level caused by exposure to 2% CO2 was significantly attenuated (*n = 8; p < 0.05, Student's t test). Error bars indicate standard error.

When ecto-ATPase was inhibited with ARL-67156 (100 μM) during hypocapnia, the increase in fEPSPs was significantly smaller than that during hypocapnia alone (Figure 6A; n = 10; p < 0.01, ANOVA). Because inhibition of ecto-ATPase did not completely occlude the effects of hypocapnia, we hypothesized that some effects might be due to pH-dependent changes in the activity of the ATP receptor (Virginio et al., 1997) or increased ATP release. We therefore blocked ATP receptors along with inhibiting ecto-ATPase. This completely attenuated the excitatory effects of 2% CO2 (Figure 6A; n = 5; p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). When ecto-ATPase was inhibited with ARL-67156, 2% CO2 no longer caused a decrease in extracellular adenosine concentration (0.01 ± 0.07 μM decrease in adenosine; Figure 6B; n = 8; p < 0.05, Student's t test). Based on these results, 2% CO2 appears to inhibit ecto-ATPase, resulting in increased ATP acting at the ATP receptor and decreased adenosine acting at the A1 receptor (see schematic, Figure 7). Decreased adenosine would enhance fEPSPs, and if ecto-ATPase is inhibited, increased ATP could further increase fEPSPs via P2 receptors. Results were similar for all conditions tested using another ATP receptor antagonist (suramin, 50 μM; data not shown).

Figure 7.

Model of Putative Mechanism for Hypocapnia-Induced Changes in Extracellular Adenosine and Neuronal Excitability

CO2 (2%) appears to cause inhibition of ecto-ATPases, which can be mimicked by inhibition with ARL-67156, resulting in increased ATP receptor activation and decreased adenosine A1 receptor activation. NT, neurotransmitter. Crosses denote site of action of antagonists DPCPX and P-PADS and the ecto-ATPase inhibitor ARL-67156.

Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Hypercapnia

We attempted to block hypercapnia-induced adenosine release and inhibition of fEPSPs by using pharmacological inhibition of adenosine-metabolizing enzymes and the nucleoside transporters. Inhibition of ecto-ATPase, ecto-5′nucleotidase, and adenosine kinase did not alter the effects of hypercapnia on either fEPSPs or adenosine release. Inhibition of the nucleoside transporter (10 μM dipyridamole) also did not attenuate the effects of hypercapnia (Figure S2). When ecto-ATPases were inhibited (100 μM ARL-67156; data not shown), 20% CO2 caused a 55.0% ± 3.8% inhibition of fEPSP amplitude (n = 6) and an increase in extracellular adenosine levels of 0.94 ± 0.24 μM (n = 6). When ecto-5′nucleotidase was inhibited (2 mM guanosine monophosphate [GMP]; data not shown), 20% CO2 caused a 42.9% ± 1.5% decrease in fEPSP amplitude (n = 6; adenosine sensor measurements were not possible during these experiments due to large sensor deviations caused by application of 2 mM GMP). When adenosine kinase was inhibited (5 μM iodotubercidin; data not shown), 20% CO2 caused a 51.2% ± 8.7% (n = 10) decrease in fEPSP amplitude, and extracellular adenosine levels rose by 1.02 ± 0.23 μM (n = 4). None of these drugs significantly altered the inhibition of the fEPSP or the changes in extracellular adenosine levels caused by 20% CO2 (p > 0.05, Student's t test). Inhibition of the nucleoside transporter (10 μM dipyridamole; n = 9) also did not attenuate the effects of hypercapnia; fEPSP amplitude was inhibited by 68.2% ± 7.2%, and extracellular adenosine levels rose by 1.20 ± 0.13 μM (Figure S2A). Blocking the nucleoside transporter did prolong the effects of hypercapnia during the return to normal CO2 levels, suggesting that adenosine reuptake via the nucleoside transporter is important in terminating the effects of hypercapnia.

Changes in CO2 Levels Affect Epileptiform Activity via Adenosine

Although hyperventilation classically induces absence seizures (Adams and Leuders, 1981), a form of thalamocortical epilepsy (Huguenard, 1999), temporal lobe seizures are also induced by hypocapnia (Miley and Forster, 1977) and originate in the hippocampus (Alarcon et al., 1997). To test whether changes in extracellular adenosine levels underlie the changes in seizure threshold associated with changes in PCO2, we examined the effects of CO2 and adenosine on a model of interictal activity in the hippocampus. Hippocampal area CA3 is characterized by an abundance of excitatory recurrent collateral synapses, creating a network of interconnected neurons (MacVicar and Dudek, 1982). After stimulation of area CA3 with a tetanic stimulation (100 Hz for 1 s), CA3 pyramidal neurons began discharging periodic synchronous bursts of action potentials (Bains et al., 1999). These bursts (see Figure 8A1) occur every 5–20 s and have a duration of approximately 100 ms, closely resembling hippocampal sharp waves and interictal activity recorded in vivo in epileptic tissue (Buzsaki, 1986). We used these bursts as an in vitro model of interictal activity. The frequency of these bursts is modulated by synaptic strength (Bains et al., 1999) and the probability of release (Staley et al., 1998) at the recurrent collateral synapses that link CA3 pyramidal cells. Because adenosine A1 receptor activation strongly decreases glutamate release probability (Scanziani et al., 1992), we hypothesized that CO2-mediated changes in adenosine should influence this form of epileptiform activity.

Figure 8.

Hypercapnia and Hypocapnia Modulate Hippocampal Epileptiform Activity in Area CA3 via Adenosine A1 and ATP Receptors

Extracellular recordings of synchronized bursting in area CA3. (A) Hypercapnia (20% CO2) reversibly attenuates bursting. Inset, left: (A1) Example of a single burst recorded during control conditions (5% CO2) (scale bars, 1 mV, 50 ms for all). (A2) Example of extracellular recording during hypercapnia, no bursts present. (Note: exact location of samples indicated on trace below.) Inset, right: Burst frequency during control and hypercapnic conditions. (B) Blocking adenosine A1 receptors with DPCPX increases tonic firing, and hypercapnia (20% CO2) did not attenuate bursting during adenosine A1 receptor blockade. Inset, left: (B1) Example of a single burst recorded during control conditions (5% CO2) with application of DPCPX. (B2) Example of a single burst recorded during hypercapnia with application of DPCPX, bursts still present. Inset, right: Burst frequency during control/DPCPX and hypercapnic/DPCPX conditions. (C) Hypocapnia (2% CO2) increases bursting frequency. Inset, left: (C1) Example of a single burst recorded during control conditions (5% CO2). (C2) Example of extracellular recording during hypocapnia. Inset, right: Burst frequency during control and hypocapnic conditions. (D) Blocking adenosine A1 receptors and ATP receptors attenuates hypocapnia-induced increases in bursting frequency. Inset, left: (D1) Example of a single burst recorded during control conditions (5% CO2). (D2) Example of extracellular recording during hypocapnia. Inset, right: Burst frequency does not change during hypocapnia when adenosine A1 receptors and ATP receptors are blocked. (E) Average percent change in burst frequency. Hypercapnia (20% CO2; n = 6) attenuates bursting, but burst frequency is not altered by hypercapnia when adenosine A1 receptors are blocked with DPCPX (n = 4; **p < 0.01, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). Hypocapnia (2% CO2) increases average burst frequency from control levels (n = 7). This increase in burst frequency is prevented when DPCPX and suramin are applied prior to exposure to 2% CO2 (n = 10; ***p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fisher PLSD). (F) Attenuation of bursting by hypercapnic buffer was not due to decreased oxygen (n = 5; ***p < 0.001, Student's t test). Error bars indicate standard error.

When slices were exposed to hypercapnia (CO2 = 20%; pH = 6.6), bursting ceased within 3–5 min (n = 6; p < 0.005, Student's paired t test; Figures 8A and 8E) as has been observed with exogenous adenosine application (Dunwiddie, 1999). This effect on burst frequency was reversible upon returning to normal CO2 levels (Figure 8A) but was not due to hypoxia, as exposure to low-oxygen buffer had no effect on bursting frequency (Figure 8F; %Δ frequency = 3.3 ± 4.9; n = 5; p < 0.001 compared to effects of 20% CO2, Student's t test).

Since adenosine levels increased by 0.66 ± 0.08 μM in area CA3 upon exposure to 20% CO2 (n = 6; data not shown), we addressed the role of adenosine in this attenuation of bursting by repeating these experiments in the presence of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX (Figures 8B and 8E). After a stable baseline frequency was established (0.06 ± 0.01 Hz), adenosine A1 receptor blockade increased burst frequency to 0.23 ± 0.02 Hz, consistent with previous studies (Thummler and Dunwiddie, 2000). When the adenosine A1 receptor was blocked with DPCPX, increasing CO2 levels from 5% to 20% did not attenuate bursting (DPCPX + hypercapnia = 0.21 ± 0.05 Hz; n = 4; Figures 8B and 8E), demonstrating that hypercapnia attenuates bursting via increased extracellular adenosine and A1 receptor activation. This change was not due to a persistent DPCPX-induced increase in baseline burst frequency (Thummler and Dunwiddie, 2000), as hypercapnia also attenuated bursting when burst frequency was increased by adding 2–4 mM potassium chloride (high potassium = 0.35 ± 0.02 Hz; high potassium + hypercapnia = 0.04 ± 0.03 Hz; n = 5; p < 0.005, Student's paired t test; data not shown). When the bursting network was exposed to hypocapnia (2% CO2), extracellular adenosine levels decreased by 0.42 ± 0.12 μM (n = 6; data not shown), and there was a corresponding increase in burst frequency (control = 0.06 ± 0.01 Hz; hypocapnia = 0.11 ± 0.02 Hz; n = 7; p < 0.001, Student's paired t test; Figures 8C and 8E). This increase in burst frequency could be occluded by combined blockade of adenosine A1 receptors and ATP receptors (n = 10; Figures 8D and 8E).

Thus, the effects of CO2 on cortical seizure activity can be attributed largely to the influence of pH-dependent changes in extracellular purines and likely explain the initiation of human epileptic seizures by hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia.

Discussion

By manipulating CO2 levels in the hippocampal slice while measuring excitatory synaptic transmission in area CA1, network bursting in area CA3, and extracellular adenosine levels, we have shown that the effects of CO2 are mediated by the combined action of adenosine A1 receptors, ATP receptors, and ecto-ATPase. Hypercapnia (increased PCO2) increases extracellular adenosine concentration, inhibits excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission, and attenuates epileptiform activity via activation of adenosine A1 receptors. These effects of hypercapnia depend on extracellular pH because blocking CO2-induced pH changes or changing pHi alone attenuates both the release of adenosine and the inhibition of excitatory potentials, currents, and seizures. In contrast, hypocapnia decreases extracellular adenosine levels and increases glutamatergic transmission and epileptiform activity. These consequences of hypocapnia are due to the combined effects of a reduced influence of adenosine A1 receptors, decreased ecto-ATPase activity, and increased ATP receptor activity.

These findings provide a physiological link between CO2 and neuronal excitability and provide a mechanism for hyperventilation-induced reduction in seizure threshold. Under normal circumstances, extracellular ATP is degraded rapidly into adenosine by enzymes that control adenine nucleotide metabolism. Pharmacological inhibition of one of these enzymes, ecto-ATPase, causes a decrease in extracellular adenosine levels, confirming that extracellular degradation of ATP is a source of extracellular adenosine (Cunha et al., 1998; Dunwiddie et al., 1997). When endogenous ATP is degraded in the hippocampus, the resulting adenosine acts primarily at the adenosine A1 receptor to inhibit neurotransmission (Cunha et al., 1998; Dunwiddie et al., 1997).

The current findings support the following mechanism for an increase in neuronal excitability when CO2 decreases. First, hypocapnia causes extracellular alkalization, which appears to inhibit ecto-ATPase (Nagy et al., 1986; Ziganshin et al., 1994). Decreased ecto-ATPase activity results in an accumulation of extracellular ATP and a decrease in extracellular adenosine. Activity at excitatory ATP receptors is therefore enhanced, while simultaneously the influence of inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors is reduced. The net result is increased excitability, consistent with the lower seizure threshold precipitated by hypocapnia (Guaranha et al., 2005).

In contrast, during hypercapnia adenosine levels rise and adenosine A1 receptors are activated, resulting in decreased neuronal excitability. In addition, the balance between ATP and adenosine appears to mediate the effects of hypercapnia. While the consequent inhibition is blocked partially by either adenosine A1 or ATP receptor antagonists, the inhibition is blocked completely by their coapplication. Our studies indicate that changes in ecto-ATPase are not involved in this hypercapnia-induced inhibition, and support the evolving concept that adenosine and ATP act in concert as neuromodulators (Pascual et al., 2005; Yoshioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003).

This study extends the findings of Gourine et al. (2005) by providing detailed electrophysiological analysis of changes in excitatory neuronal activity during changes in CO2 level beyond the brainstem, and furthering the role of the purines ATP and adenosine as a widespread chemosensory transduction mechanism for responding to changes in CO2 level and tissue pH. The current study also suggests that changes in ATP levels that occur in the medulla during increases in CO2 level (Gourine et al., 2005) may be due to pH-dependent changes in the metabolism of ATP by ecto-ATPase, although different mechanisms may exist in different brain regions. While CO2 can affect physiological processes via serotonergic systems, the present results, combined with those of Gourine et al. (2005) suggest that the purines ATP and adenosine also play a significant role. Notably, the decreased extracellular adenosine levels and altered adenosine A1 and ATP receptor activation caused by hypocapnia provide a plausible mechanism for hyperventilation-induced epileptic seizures in vulnerable humans. Furthermore, an enhanced understanding of an ongoing regulation of these ubiquitous and influential neuromodulatory purines holds promise for both basic research questions and important clinical applications, including epilepsy, chronic pain, and sleep and respiratory disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Slice Preparation

For fEPSP recordings, transverse hippocampal slices were obtained from 4- to 8-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats by using standard procedures (Dunwiddie and Lynch, 1978), as approved by the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Animal Care and Use Committee. After decapitation into ice-cold aCSF (see composition below), 400 μm slices were made on a Sorvall TC-2 tissue chopper and were incubated at 32.5°C. The aCSF used for dissection, incubation, and submerged, perfused recordings contained the following: 126.0 mM NaCl, 3.0 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 11 mM D-glucose, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, and 25.9 mM NaHCO3 (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) bubbled continuously with a 95% O2/5% CO2 mixture, unless otherwise noted. Slices were incubated undisturbed for 60 min before electrophysiological recording.

For whole-cell recordings, horizontal hippocampal slices (250 μm thick) were cut using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) in a cutting solution of the following composition: 75 mM sucrose, 87 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM glucose, 25 mM NaCO3, continuously bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 at 4°C. Slices were stored in a submersion chamber in 50% cutting solution, 50% aCSF at 32°C for at least 1 hr before recording.

Electrophysiological Recording

For extracellular recordings, slices were placed on a nylon net in the recording chamber and superfused continuously (2 ml/min) with aCSF bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Control aCSF contains 5% CO2 and 26 mM NaHCO3 with an equilibrium pH of 7.4. Extracellular field EPSPs were recorded from the CA1 region of the stratum radiatum by using glass micropipettes (10–15 MΩ) filled with 3 M NaCl. A twisted bipolar insulated tungsten stimulating electrode (0.002 inch wire diameter) was placed to stimulate the Schaffer collaterals in stratum radiatum every 10 s. Stimulation intensity was adjusted such that the fEPSP was between 0.5 and 1.5 mV. Data were recorded via an AC amplifier (World Precision Instruments), filtered between 1 Hz and 3 kHz, and digitized at a rate of 3 kHz. All solutions were continuously perfused to avoid degassing in the perfusion lines. All time courses of fEPSPs are moving averages of five data points. Field fEPSPs were quantified by measuring the change in amplitude over time for all experiments except when GABAA receptors were blocked, in which case, fEPSPs were quantified by measuring the change in initial slope of the fEPSP over time. All measurements were taken 10–15 min after exposure to CO2 manipulation in order to quantify steady-state changes.

For whole-cell recordings, a slice was transferred to a submerged recording chamber and continuously perfused with aCSF at 32°C with a bath flow of 3 ml/min. The slice was allowed to equilibrate in the recording chamber for at least 15 min before recording began. Recording electrodes were fabricated from borosilicate capillary glass (1.5 mm o.d., 0.86 mm i.d.; Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA) using a horizontal puller (model P-97 micro-pipette puller; Sutter Instrument Co, Novato, CA) yielding resistances of 4–6 MΩ when filled with a cesium-based internal solution containing the following: 140 mM Cs-MeSO3, 8 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgATP, 0.3 mM Na3GTP, and 5 mM QX-314, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH, 290 mOsm. Pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region were recorded from using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. Pyramidal neurons were visualized with infrared differential interference contrast microscopy (IR DIC) using a Nikon E600FN microscope. Access resistance was typically between 10 and 40 MΩ. Access resistance, input resistance, whole-cell capacitance, and membrane time constant were all monitored using the “membrane test” function in PClamp 9 acquisition software. Data were only used from neurons in which the access resistance changed less than 20% during the course of the experiment. Synaptic currents were elicited using a NiCr bipolar electrode to stimulate the Schaffer collateral input to the CA1 pyramidal neurons. Stimulus intensity was adjusted to achieve stable baseline PSCs. Data were acquired using PClamp 9. Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. EPSC and IPSC amplitude was measured versus time to quantify all changes in whole-cell currents.

Burst Induction

Bursting in CA3 was induced by tetanic stimulation of the CA3 pyramidal cell layer. The recording electrode was placed in the cell layer of area CA3, and the simulating electrode was place in close proximity, allowing for orthodromic stimulation of CA3 pyramidal cells. The tetanic stimulus consisted of a 100 Hz, 1 s train of stimuli that were of sufficient amplitude to elicit a population spike when delivered at a lower frequency. If a single tetanus did not induce bursting, it was repeated after a 10 min interval. When bursting was induced by tetanic stimulation, extracellular solutions were modified to 1.3 mM Ca2+, 0.9 mM Mg2+, and 3.3 mM K+ (Stasheff et al., 1985). Time course of bursting frequency are moving averages of five data points.

pH Imaging

Slices were placed into a 1.5 ml dark glass tube and loaded with BCECF-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon). Slices were incubated in 5–20 μM dye in aCSF plus 0.0133% anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 6.0 × 10−5% pluronic acid, and 5 mM probenecid. Slices were incubated in dye solution at physiological temperature for at least 30 min. Slices were then placed in a recording chamber and perfused normally. Slices were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. A Coherent Mira Ti:Sapphire IR laser was used for two-photon excitation at the pH-sensitive wavelength (795 nM), and fluorescence was detected at 535 nM. In vitro calibrations of BCECF-AM were done using a technique involving dye saturation. A series of solutions mimicking the intracellular milieu were titrated to different pHs (11 mM glucose, 25 mM HEPES, 120 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM NaCl). BCECF-free acid (10 μM) was added to these solutions, and the relative fluorescence was measured. A calibration curve was created comparing percent maximum fluorescence of the dye versus pH. pHi was calculated by then exposing BCECF-loaded cells to different pH manipulations and then applying 40 mM NH4Cl. This causes intracellular alkalization and increases the dye fluorescence to its maximum value. Percent maximum fluorescence before application of NH4Cl was calculated and plotted against the calibration curve (Figure S4). Baseline fluorescence was taken for at least 1.5 min prior to manipulations, and all data were subtracted from a baseline bleaching curve extrapolated from the 1.5 min baseline. The average in F/F0 was computed by dividing the average of five steady-state peak fluorescence measurements 2–4 min after changing the CO2 level by the average of five fluorescence measurements directly preceding the CO2 change. For all fluorescence experiments, autofluorescence was analyzed by monitoring an unloaded slice during all experimental manipulations. No significant changes in autofluorescence were seen for any manipulation tested. Extracellular pH was taken to be equivalent to aCSF buffer pH (Lee et al., 1996).

Adenosine Sensor

An enzymatic sensor was used to measure adenosine release in rat hippocampal slices (Dale et al., 2000). The sensor (Sycopel International Ltd, Tyne & Wear, UK) is comprised of two identical parallel semipermeable barrels. Each barrel contains a 50 μm platinum wire polarized to +650 mV using a potentiostat (Sycopel International Ltd.). One barrel is filled with adenosine deaminase, nucleoside phosphorylase, and xanthine oxidase. This enzyme combination results in the breakdown of adenosine to inosine to hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide is oxidized on the platinum wire to yield a current proportional to the concentration of adenosine. In the second barrel, the enzyme combination lacks adenosine deaminase and is thus referred to as the reference barrel. The two barrels are calibrated before each experiment with 2 μM adenosine and 2 μM inosine. Sensor differential recordings were created by recording each barrel's current separately (8× amplification using differential amplifiers built in-house, sampled at 200 Hz, no filtering) and then subtracting one recording from the other based on calibrations using software created in-house. A differential recording between the two barrels yields a current (nA/V) that is linearly related to the concentration of adenosine. The sensor was characterized for its pH sensitivity by performing concentration-response curves for adenosine at different pH levels. All aCSF buffers were characterized, and data were analyzed as a percent of the control peak of the adenosine response. CO2 (20%) caused a significant decease in adenosine sensitivity (22% ± 9%; Figure S5), and thus all adenosine sensor measurements were corrected by this factor. No other buffers caused a significant change in adenosine sensitivity.

Drugs and Chemicals

Adenosine, inosine, DPCPX, P-PADS, ARL-67156, suramin, xanthine oxidase, nucleotide phosphorylase, adenosine deaminase, GMP, iodotubercidin, DMSO, dipyridamole, picrotoxin, propionic acid, and probenecid were all obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri) and dissolved in water unless noted below. Anhydrous DMSO was obtained from Pierce Co. (Rockford, Illinois). Pluronic acid was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon). All salts were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri). DPCPX, picrotoxin, and dipyridamole were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted 1:10 to make a final DMSO concentration of 10% (100×, 0.1% final concentration DMSO). Probenecid was dissolved in 2 ml 1 N NaOH, then titrated back to pH 7.4 by addition of 800 ml 1 N HCl and then diluted to a total of 20 ml in water. Iodotubercidin was dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with water to a final concentration of 33.3% DMSO (100×, 0.33% final concentration DMSO).

Analysis

Statistical significance for all experiments was determined using Student's unpaired and paired t tests, ANOVA, and Fisher PLSD tests as appropriate. All time courses are moving averages of five data points.

Supplementary materials

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (NINDS) and by the Epilepsy Foundation through the generous support of the American Epilepsy Society. The work in the B.G.F. laboratory was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Anonymous Trust, Tenovus Scotland, and the Epilepsy Research Foundation. We are grateful to Professor Nicholas Dale for valuable comments and to Mr. John Bell (Sycopel International) for the manufacture of the adenosine sensors. We would like to thank the Light Microscopy Core Facility at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data

The Supplemental Data include five supplemental figures and can be found with this article online at http://www.neuron.org/cgi/content/full/48/6/■ ■ ■/DC1/.

References

- Achenbach-Ng J, Siao TC, Mavroudakis N, Chiappa KH, Kiers L. Effects of routine hyperventilation on PCO2 and PO2 in normal subjects: implication for EEG interpretations. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1994;11:220–225. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D, Leuders H. Hyperventilation and 6-hour EEG recording in evaluation of absence seizures. Neurology. 1981;31:1175–1177. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon G, Garcia Seoane JJ, Binnie CD, Martin Miguel MC, Juler J, Polkey CE, Elwes RD, Ortiz Blasco JM. Origin and propagation of interictal discharges in the acute electrocorticogram. Implications for pathophysiology and surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 1997;120:2259–2282. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.12.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida T, Rodrigues RJ, de Mendonca A, Ribeiro JA, Cunha RA. Purinergic P2 receptors trigger adenosine release leading to adenosine A2A receptor activation and facilitation of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 2003;122:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aram JA, Lodge D. Epileptiform activity induced by alkalosis in rat neocortical slices: block by antagonists of N-methyl-D-aspartate. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;83:345–350. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains J, Longacher M, Staley K. Reciprocal interactions between CA3 network activity and strength of recurrent collateral synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:720–726. doi: 10.1038/11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrino M, Somjen GG. Concentration of carbon dioxide, interstitial pH and synaptic transmission in hippocampal formation of the rat. J. Physiol. 1988;396:247–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Jiang J, Zhu C, Lu Y, Cai R, Ma C. Effect of hyperventilation on brain tissue oxygen pressure, carbon dioxide pressure, pH value and intracranial pressure during intracranial hypertension in pigs. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2000;3:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Huber A, Padrun V, Deglon N, Aebischer P, Mohler H. Seizure suppression by adenosine-releasing cells is independent of seizure frequency. Epilepsia. 2002;43:788–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.33001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Pieribone VA, Wang W, Severson CA, Jacobs RA, Richerson GB. Chemosensitive serotonergic neurons are closely associated with large medullary arteries. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:401–402. doi: 10.1038/nn848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brian JE., Jr. Carbon dioxide and the cerebral circulation. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1365–1386. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199805000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Introduction: P2 receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004;4:793–803. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Hippocampal sharp waves: their origin and significance. Brain Res. 1986;398:242–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps RT. Carbon dioxide. Clin. Anesth. 1968;3:122–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler M. Regulation and modulation of pH in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:1183–1221. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA, Sebastiao AM, Ribeiro JA. Inhibition by ATP of hippocampal synaptic transmission requires localized extra-cellular catabolism by ecto-nucleotidases into adenosine and channeling to adenosine A1 receptors. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1987–1995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01987.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. Delayed production of adenosine underlies temporal modulation of swimming in frog embryo. J. Physiol. 1998;511:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.265bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Pearson T, Frenguelli BG. Direct measurement of adenosine release during hypoxia in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampal slice. J. Physiol. 2000;526:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto C, Rai AK, Ilivicky HJ, Caroff SN. Augmentation of seizure induction in electroconvulsive therapy: a clinical reappraisal. J. ECT. 2002;18:118–125. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakulich DA, Spellmon C, Hexum TD. Effect of the ecto-ATPase inhibitor, ARL 67156, on the bovine chromaffin cell response to ATP. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;485:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV. Adenosine and suppression of seizures. Adv. Neurol. 1999;79:1001–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Diao LH. Extracellular adenosine concentrations in hippocampal brain slices and the tonic inhibitory modulation of evoked excitatory responses. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:537–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Lynch GS. Long-term potentiation and depression of synaptic responses in the rat hippocampus: localization and frequency dependency. J. Physiol. 1978;276:353–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Diao L, Proctor WR. Adenine nucleotides undergo rapid, quantitative conversion to adenosine in the extracellular space in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7673–7682. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07673.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherington LA, Frenguelli BG. Endogenous adenosine modulates epileptiform activity in rat hippocampus in a receptor subtype-dependent manner. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:2539–2550. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:239–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N, Abe T, Endoh H, Warashina A, Shimoji K. Changes in intracellular pH of mouse hippocampal slices responding to hypoxia and/or glucose depletion. Brain Res. 1992;572:335–339. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90496-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla AE, Pearson T, Currie AJ, Dale N, Hawley SA, Sheehan M, Hirst W, Michel AD, Randall A, Hardie DG, Frenguelli BG. AICA riboside both activates AMP-activated protein kinase and competes with adenosine for the nucleoside transporter in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1272–1282. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Llaudet E, Dale N, Spyer KM. ATP is a mediator of chemosensory transduction in the central nervous system. Nature. 2005;436:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature03690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JG, Foga IO, Parkinson FE, Geiger JD. Involvement of bidirectional adenosine transporters in the release of L-[3H]adenosine from rat brain synaptosomal preparations. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:2105–2110. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaranha MS, Garzon E, Buchpiguel CA, Tazima S, Yacubian EM, Sakamoto AC. Hyperventilation revisited: physiological effects and efficacy on focal seizure activation in the era of video-EEG monitoring. Epilepsia. 2005;46:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.11104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR. Neuronal circuitry of thalamocortical epilepsy and mechanisms of antiabsence drug action. Adv. Neurol. 1999;79:991–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RP, Lin SZ, Long RT, Paul SM. N-methyl-D-aspartate induces a rapid, reversible, and calcium-dependent intra-cellular acidosis in cultured fetal rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:1352–1357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01352.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA, Poelchen W, Gimenez-Llort L, Escorihuela RM, Fernandez-Teruel A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ, et al. Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adeno-sine A1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9407–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161292398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuri AR, Dobrowsky E, Tannock IF. Selective cellular acidification and toxicity of weak organic acids in an acidic microenvironment. Br. J. Cancer. 1993;68:1080–1087. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors and ATP signalling at synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:165–174. doi: 10.1038/35058521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Gittermann D, Cockayne DA, Jones A. ATP modulation of excitatory synapses onto interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7426–7437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07426.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Taira T, Pihlaja P, Ransom BR, Kaila K. Effects of CO2 on excitatory transmission apparently caused by changes in intracellular pH in the rat hippocampal slice. Brain Res. 1996;706:210–216. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar BA, Dudek FE. Local circuit interactions in rat hippocampus: interactions between pyramidal cells. Brain Res. 1982;242:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malva JO, Silva AP, Cunha RA. Presynaptic modulation controlling neuronal excitability and epileptogenesis: role of kainate, adenosine and neuropeptide Y receptors. Neurochem. Res. 2003;28:1501–1515. doi: 10.1023/a:1025618324593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masino SA, Dunwiddie TV. Temperature-dependent modulation of excitatory transmission in hippocampal slices is mediated by extracellular adenosine. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1932–1939. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01932.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Fernandez V, Andrew RD, Barajas-Lopez C. ATP inhibits glutamate synaptic release by acting at P2Y receptors in pyramidal neurons of hippocampal slices. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miley CE, Forster FM. Activation of partial complex seizures by hyperventilation. Arch. Neurol. 1977;34:371–373. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1977.00500180065014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Heuss C, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. Fast synaptic transmission mediated by P2X receptors in CA3 pyramidal cells of rat hippocampal slice cultures. J. Physiol. 2001;535:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/nn1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy AK, Shuster TA, Delgado-Escueta AV. EctoATPase of mammalian synaptosomes: identification and enzymic characterization. J. Neurochem. 1986;47:976–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov Y, Castro E, Miras-Portugal MT, Krishtal O. A purinergic component of the excitatory postsynaptic current mediated by P2X receptors in the CA1 neurons of the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:3898–3902. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov Y, Lalo U, Castro E, Miras-Portugal MT, Krishtal O. ATP receptor-mediated component of the excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Prog. Brain Res. 1999;120:237–249. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov YV, Lalo UV, Krishtal OA. Role for P2X receptors in long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:8363–8369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08363.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Nuritova F, Caldwell D, Dale N, Frenguelli BG. A depletable pool of adenosine in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:2298–2307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02298.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrn1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues RJ, Almeida T, Richardson PJ, Oliveira CR, Cunha RA. Dual presynaptic control by ATP of glutamate release via facilitatory P2X1, P2X2/3, and P2X3 and inhibitory P2Y1, P2Y2, and/or P2Y4 receptors in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6286–6295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0628-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of miniature excitatory synaptic currents by baclofen and adenosine in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson CA, Wang W, Pieribone VA, Dohle CI, Richerson GB. Midbrain serotonergic neurons are central pH chemoreceptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:1139–1140. doi: 10.1038/nn1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperlagh B, Kofalvi A, Deuchars J, Atkinson L, Milligan CJ, Buckley NJ, Vizi ES. Involvement of P2X7 receptors in the regulation of neurotransmitter release in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:1196–1211. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Longacher M, Bains JS, Yee A. Pre-synaptic modulation of CA3 network activity. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:201–209. doi: 10.1038/651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasheff SF, Bragdon AC, Wilson WA. Induction of epileptiform activity in hippocampal slices by trains of electrical stimuli. Brain Res. 1985;344:296–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummler S, Dunwiddie T. Adenosine receptor antagonists induce persistent bursting in the rat hippocampal CA3 region via an NMDA receptor-dependent mechanism. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1787–1795. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Calker D, Muller M, Hamprecht B. Adenosine regulates via two different types of receptors, the accumulation of cyclic AMP in cultured brain cells. J. Neurochem. 1979;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginio C, Church D, North RA, Surprenant A. Effects of divalent cations, protons and calmidazolium at the rat P2X7 receptor. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirrell EC, Camfield PR, Gordon KE, Camfield CS, Dooley JM, Hanna BD. Will a critical level of hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia always induce an absence seizure? Epilepsia. 1996;37:459–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Hosoda R, Kuroda Y, Nakata H. Hetero-oligomerization of adenosine A1 receptors with P2Y1 receptors in rat brains. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JM, Wang HK, Ye CQ, Ge W, Chen Y, Jiang ZL, Wu CP, Poo MM, Duan S. ATP released by astrocytes mediates glutamatergic activity-dependent heterosynaptic suppression. Neuron. 2003;40:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziganshin AU, Hoyle CH, Burnstock G. Ectoenzymes and metabolism of extracellular ATP. Drug Dev. Res. 1994;32:134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn-Schmeideberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.