Abstract

BACKGROUND

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour requirements may affect residents' understanding and practice of professionalism.

OBJECTIVE

We explored residents' perceptions about the current teaching and practice of professionalism in residency and the impact of duty hour requirements.

DESIGN

Anonymous cross-sectional survey.

PARTICIPANTS

Internal medicine, neurology, and family practice residents at 3 teaching hospitals (n = 312).

MEASUREMENTS

Using Likert scales and open-ended questions, the questionnaire explored the following: residents' attitudes about the principles of professionalism, the current and their preferred methods for teaching professionalism, barriers or promoters of professionalism, and how implementation of duty hours has affected professionalism.

RESULTS

One hundred and sixty-nine residents (54%) responded. Residents rated most principles of professionalism as highly important to daily practice (91.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 90.0 to 92.7) and training (84.7%, 95% CI 83.0 to 86.4), but fewer rated them as highly easy to incorporate into daily practice (62.1%, 95% CI 59.9 to 64.3), particularly conflicts of interest (35.3%, 95% CI 28.0 to 42.7) and self-awareness (32.0%, 95% CI 24.9 to 39.1). Role-modeling was the teaching method most residents preferred. Barriers to practicing professionalism included time constraints, workload, and difficulties interacting with challenging patients. Promoters included role-modeling by faculty and colleagues and a culture of professionalism. Regarding duty hour limits, residents perceived less time to communicate with patients, continuity of care, and accountability toward their colleagues, but felt that limits improved professionalism by promoting resident well-being and teamwork.

CONCLUSIONS

Residents perceive challenges to incorporating professionalism into their daily practice. The duty hour implementation offers new challenges and opportunities for negotiating the principles of professionalism.

Keywords: medical education, residency, professionalism, work hours

Since the publication of the 2002 American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Charter on Professionalism, several medical societies have endorsed the renewed call for enhancing professionalism's place in the practice and teaching of medicine.1,2 In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Outcome Project included professionalism as 1 of its 6 core competencies.3 The ACGME duty hour requirements, which limit residents' work hours to improve patient safety and resident well-being, may offer new challenges to residents' understanding and practice of professionalism.4 In this climate of organizational change to improve duty hour compliance, some have raised concerns about how these changes will affect the promotion of altruism and competence in residency education.5,6

Understanding residents' perspectives about the principles of professionalism, especially in the context of duty hour requirements, may help educators to teach residents about professionalism with learner-centered methods that incorporate their daily challenges as teachable moments. Prior surveys have assessed resident perspectives on professionalism,7,8 but no study has specifically examined the impact of ACGME duty hour implementation on residents' perceptions of the importance and practice of professionalism.

We designed a survey to explore the perspectives of residents about the importance of professionalism, current training in this domain, barriers and promoters of putting professionalism into practice, and the impact of the ACGME duty hour requirements on attitudes about professionalism in residency.

METHODS

Sample Population

We surveyed residents in internal medicine (IM), neurology, and family practice (FP) currently employed at 3 institutions: Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHB), and the University of Virginia Health System (UVA). The total number of sampled programs was 6; at Johns Hopkins, there is no FP program, and the 2 hospitals share 1 combined neurology program. The survey was conducted as a needs assessment for developing a professionalism curriculum for the 6 residency programs in these disciplines at these institutions. The programs were also selected for sampling because they train residents in adult clinical care in acute inpatient and ambulatory settings. We included residents from all postgraduate years (PGYs) enrolled in the programs in spring 2005. The eligible sample population comprised 312 total residents: JHH IM (n = 108), JHH neurology (n = 24), JHB IM (n = 46), UVA IM (n = 94), UVA neurology (n = 15), and UVA FP (n = 25).

Instrument Design and Survey Method

We identified 13 primary principles of professionalism based on the ABIM Charter and ACGME Outcomes Project, review of prior studies about resident experiences with professional and unprofessional behavior, and discussions with the faculty and program administration for the residency programs.1,3 We designed a survey to explore residents' attitudes about the principles of professionalism, current methods for teaching professionalism, their preferred methods for learning about professionalism, barriers or promoters of professionalism, and how implementation of duty hours has affected professionalism. To enhance face and content validity, the authors developed the instrument in an iterative process over 3 months, through discussions with the program directors and key faculty about salient issues in professionalism training. The survey was piloted among a group of general IM fellows and faculty. Portions of the survey used Likert scales, while questions about barriers and promoters used open-ended questions to encourage responses free from investigator influence. Demographic data collected included program, PGY of training, and gender.

From February to June 2005, we distributed and collected surveys at teaching conferences; participation and responses were anonymous. A raffle for 2 $250 gift certificates served as an incentive, and raffle entries were collected separately from respondents' surveys. Institutional Review Boards at Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia approved this study.

Data Analysis

We analyzed quantitative data using STATA Intercooled version 8.0 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, 2002). We used χ2 tests to compare categorical variables and frequency distributions to describe Likert scale ratings and perceptions of teaching methods.

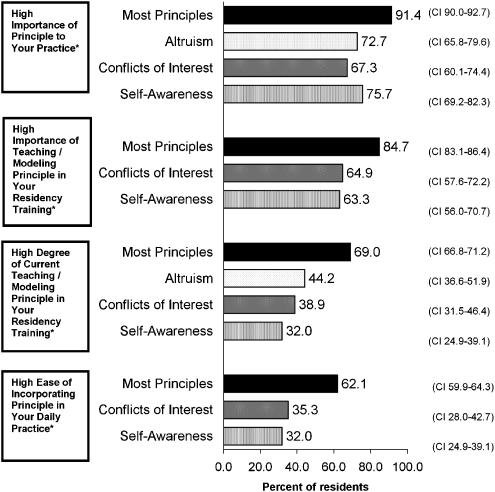

To analyze responses for questions about the principles of professionalism, we compared 95% confidence intervals (CI) for proportions of responses ≥6 on a scale of 1 to 7. Principles with ratings that did not differ significantly were combined into 1 variable “Most Principles” to simplify presentation (Fig. 1). The average proportions of respondents who rated these principles ≥6 are presented with their 95% CIs. For principles displayed separately, the proportion of responses ≥6 are significantly different from the proportion of responses for the “Most Principles” category, as demonstrated by nonoverlapping 95% CIs (P < 0.05). Respondents' median Likert ratings for each of the principles were also analyzed using nonparametric tests, including the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test and the Mann-Whitney U test, which yielded similar results.

FIGURE 1.

Percent of residents who rated highly* the importance of practicing and teaching, the current degree of teaching, and the ease of incorporating 13 principles of professionalism.†‡ *High, ≥6 on a 7-point scale, where 1 = not at all and 7 = extremely. †Thirteen principles: altruism, respect, sensitivity, accountability, confidentiality, communication and shared decision making, integrity, compassion and empathy, duty, competence, managing conflicts of interest, self-awareness, and commitment to excellence and ongoing professional development. These were defined for respondents (Appendix). ‡For principles with responses demonstrating no significant differences by 95% confidence intervals (CI), responses were combined into 1 variable “most principles” to simplify presentation. Responses displayed as separate principles are significantly different (P < 0.05) from the category “most principles,” as demonstrated by nonoverlapping 95% CI

For open-ended responses, we analyzed responses using the “editing organizing style” of qualitative analysis, by which themes emerge from the data itself rather than modifying the data to fit a preexisting template.9 Two researchers (N.R. and E.H.) independently developed a list of themes from the answers, negotiating discrepancies in theme selection and application. The final themes were applied to the data and tabulated for frequency counts. For each question, we selected, for this paper, 2 or 3 themes that emerged most frequently from the responses. We selected 1 or 2 quotes that best illustrated those themes, with all authors corroborating the choice of quotes for the paper.

RESULTS

Response Rate and Characteristics of Respondents

One hundred and sixty-nine residents (54%) responded to the survey. Response rate by institution was as follows: 45% (n = 59) from JHH, 74% (n = 34) from JHBMC, and 58% (n = 76) from UVA. Response rates by program were as follows: 56% (n = 138) for IM, 38% (n = 15) for neurology, and 48% (n = 12) for FP. Response rates by PGY were as follows: 74% (n = 74) PGY-1, 45% (n = 44) PGY-2, 42% (n = 41) PGY-3, 19% (n = 2) PGY-4 or PGY-5. Males comprised 53% (n = 90) of respondents and females 43% (n = 72). Seven respondents (4%) provided incomplete demographic data. Compared with nonresponders, responders included a significantly higher proportion of JHBMC, IM, and PGY-1 residents and a significantly lower proportion of JHH, neurology, and upper level residents (P < 0.05).

Importance, Practice, and Teaching of Professionalism in Residency

For each of 13 principles, we asked residents to rate responses to 4 questions on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely): (1) How important is this principle to your practice?; (2) How important is it to teach/model this principle in your residency training?; (3) To what degree is this principle already being taught/modeled in your residency?; and (4) How easy is it to incorporate/exercise this principle in your daily practice? Accompanied by brief definitions, the 13 principles included altruism, respect, sensitivity, accountability, confidentiality, communication and shared decision making, integrity, compassion and empathy, duty, competence, managing conflicts of interest, self-awareness, and commitment to excellence and ongoing professional development (Appendix).

Respondents' perceptions regarding the principles of professionalism in residency are presented in Figure 1, with ratings ≥6 representing “high” on the Likert scale. The majority of residents felt that the principles of professionalism are highly important to their practice (91.4%, CI 90.0 to 92.7) and that it is highly important for these principles to be taught or modeled in residency (84.7%, CI 83.0 to 86.4). A significantly smaller majority of residents felt that these principles are being taught or role-modeled to a high degree in their residency programs (69.0%, CI 66.8 to 71.2), and even fewer found it highly easy to incorporate these principles into their daily practice (62.1%, CI 59.9 to 64.3). Residents rated the principles of conflicts of interest and self-awareness significantly lower than the other principles for all questions (P < 0.05). Residents rated altruism lower in importance to their practice and in current degree of teaching/modeling than most other principles (P < 0.05). Respondents rarely exercised the option to suggest and rank additional principles.

Most residents (61%, n = 96) felt that appropriate time was devoted to teaching about professionalism, but 35% (n = 55) residents felt that there was not enough time and 4% (n = 6) felt there was too much time. Most residents felt that professionalism was taught formally—through lectures, conferences, or discussions—twice a year or more frequently (70.7%, n = 116). Most residents felt that professionalism was taught informally—through role-modeling or de-briefing of experiences—daily or weekly (78.9%, n = 131). Most residents felt that professionalism should be taught formally every 3 months or more frequently (75.3%, n = 125) and taught informally daily (70.2%, n = 118).

Residents' perceptions of teaching methods are displayed in Table 1. Residents rated role-modeling by attendings (69%, n = 114) and by colleagues (58%, n = 97) as methods used a large amount (4 on 4-point scale) in their training. The methods they rated as used a small amount or not at all (≤2 on 4-point scale) were standardized patients (84%, n = 140), role-plays (85%, n = 142), and videotaped patient-physician interactions (85%, n = 141). The teaching methods that residents preferred (≥4 on 5-point scale) were role-modeling by attendings (85%, n = 145) and colleagues (80%, n = 130) and evaluation/feedback (75%, n = 122). The methods that residents opposed (≤2 on 5-point scale) were standardized patients (73%, n = 117), role-plays (72%, n = 117), and videotaped patient-physician interactions (63%, n = 101).

Table 1.

Methods for Teaching Professionalism During Residency Training as Perceived by Residents at 3 Institutions*,†

| N | Percentage of Respondents§ | |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching methods rated as used a large amount‡ | ||

| Role-modeling by attendings | 114 | 69 |

| Role-modeling by colleagues | 97 | 58 |

| Teaching methods rated as used a small amount or not at all‡ | ||

| Role-play | 142 | 85 |

| Videotaped patient-physician interactions | 141 | 85 |

| Standardized patients | 140 | 84 |

| Teaching methods rated as preferred∥ | ||

| Role-modeling by attendings | 145 | 85 |

| Role-modeling by colleagues | 130 | 80 |

| Evaluation and feedback | 122 | 75 |

| Teaching methods rated as opposed§ | ||

| Role-play | 117 | 72 |

| Videotaped patient-physician interactions | 101 | 63 |

| Standardized patients | 117 | 73 |

Teaching methods assessed were: role-modeling by faculty attendings, reflection/discussion of experiences, integration into existing education (e.g., noon conference), role modeling by colleagues, resident support group, evaluation and feedback, mentor program, videotaped patient-physician interactions, standardized patients, role-play, case-based scenarios, reading packet, web-based course, lectures, group problem-solving exercises, and other (specify).

For these results, only the methods with the largest percentages are displayed.

On a Likert ratings scale 0 to 4, “a large amount” = 4 and “a small amount or not used” < = 2

Small numbers of the 169 respondents did not answer individual questions (range of nonresponses 1 to 10), and reported percentages are based on total respondents for each question.

On a Likert ratings scale 1 to 5, “preferred” ≥4 and “opposed” ≤2

Barriers and Promoters of Professionalism in Residency

We asked residents to list the top 3 barriers to practicing professionalism (as defined by the 13 principles) and top 3 factors that promote professionalism in their daily lives at their institutions (Table 2). In their narrative responses to our open-ended questions, the most commonly cited barrier to practicing professionalism was time constraints, followed by workload. In describing time constraints, 1 resident wrote:

Table 2.

Barriers to and Promoters of Professionalism as Perceived by Residents at 3 Institutions

| N | Percentage of Respondents* | |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | ||

| Time constraints | 87 | 51.5 |

| High workload | 37 | 21.9 |

| Working with challenging or difficult patients | 27 | 16.0 |

| Lack of education, including discussions, role-modeling, or feedback | 21 | 12.4 |

| Culture of medicine in general, at the institution, or in the residency | 15 | 8.9 |

| Fatigue | 13 | 7.7 |

| System constraints and lack of resources | 12 | 7.1 |

| Duty hours implementation | 11 | 6.5 |

| Interpersonal conflict with other residents, consultants, or staff | 10 | 5.9 |

| Lack of continuity of care | 6 | 3.6 |

| Conflicts of interest | 6 | 3.6 |

| Personal needs competing with professional responsibilities | 5 | 3.0 |

| No barriers | 3 | 1.8 |

| No response | 29 | 17.2 |

| Promoters | ||

| Role-modeling in general or by faculty | 95 | 56.2 |

| Role-modeling and support by colleagues | 46 | 27.2 |

| Culture of professionalism within residency or institution | 32 | 18.9 |

| Integrity to personal values or a personal sense of duty | 17 | 10.1 |

| Formal education through lectures or integrated into conferences | 13 | 7.7 |

| Discussions with faculty and colleagues | 13 | 8.8 |

| Interactions and experiences with patients | 10 | 5.9 |

| Respect from others | 6 | 3.6 |

| More time | 5 | 3.0 |

| Competence | 5 | 3.0 |

| Staff | 4 | 2.4 |

| Feedback on personal behavior | 3 | 1.8 |

| Autonomy | 2 | 1.2 |

| No response | 31 | 18.3 |

Because multiple or no responses were possible in each category, the percentages do not add to 100%.

It takes time to demonstrate empathy/compassion to patients.

Another resident declared:

Being overworked and tired makes it hard to act graciously or …to take the time required to do things right.

The third most commonly cited barrier was working with patients described as challenging or difficult. As 1 resident stated:

It is a difficult population that often lacks education and is often noncompliant (this makes sensitivity and empathy difficult at times).

The 2 primary factors promoting professionalism were role-modeling by faculty and colleagues, with 1 resident noting “actions speak louder than words.” One resident wrote:

Role models—both faculty, fellows, as well as colleagues—provide the best form of promoting professionalism.

Another resident lauded the interactions among his colleagues:

Professional behavior between colleagues and mutual respect is a self-fulfilling prophecy. People who are treated well, trusted, and respected will live up to the excellence expected from them. This is almost universally the case at our institution.

The third most commonly cited factor for promoting professionalism was the culture of the institution itself. As 1 resident wrote:

The institution as a whole seems to value patient opinions in making decisions.

Similar responses about barriers and promoters were mentioned in all programs and institutions.

Duty Hour Requirements' Impact in Reducing or Promoting Professionalism

We asked residents to describe the impact of the duty hour requirements on the practice of professionalism. Using a 5-point Likert scale, 45% of residents (n = 67) felt professionalism had been reduced, 32% (n = 47) felt there was no change, and 19% (n = 28) felt professionalism had improved. There were no differences in responses by gender (χ2 = 1.30, P = 0.5) or by PGY (χ2 = 8.94, P = 0.348).

In narrative responses to open-ended questions, residents elaborated on the ways in which the duty hour requirements reduced or promoted professionalism (Table 3). Of note, PGY-1 residents comprised 61% and 44% of the nonrespondents for these open-ended questions, respectively, with some specifically refraining to answer due to lack of prior residency experience. Residents cited both ways in which the requirements had reduced and promoted professionalism, often regardless of their chosen numerical rating about the overall impact of the requirements.

Table 3.

How Duty Hour Limits have Reduced or Promoted Professionalism as Perceived by Residents at 3 Institutions

| N | Percentage of Respondents* | |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing professionalism | ||

| Less time to talk with patients or families | 32 | 18.9 |

| Time pressure in general (excluding less time to talk with patients/families) | 28 | 16.6 |

| Continuity reduced | 24 | 14.2 |

| Duty/accountability reduced | 22 | 13.0 |

| Education reduced | 6 | 3.6 |

| Altruism reduced | 6 | 3.6 |

| Empathy/shared decision making reduced | 5 | 3.0 |

| Competence reduced | 4 | 2.4 |

| Emphasis shifted away | 4 | 2.4 |

| No reduction | 20 | 11.8 |

| No response | 51 | 30.2 |

| Promoting professionalism† | ||

| Less fatigue | 30 | 17.8 |

| Teamwork | 12 | 7.1 |

| Communication with other providers | 8 | 4.7 |

| Time increased/stress reduced | 8 | 4.7 |

| Personal well-being | 8 | 4.7 |

| Competence | 7 | 4.1 |

| Professional growth/perspective/self- awareness | 5 | 3.0 |

| Overall promotion | 2 | 1.2 |

| Education improved | 2 | 1.2 |

| No promotion | 39 | 23.1 |

| No response | 52 | 30.8 |

Because multiple or no responses were possible in each category, the percentages do not add to 100%.

Many residents stated that they felt they had less time to talk with patients and families under the duty hour requirements. One resident wrote:

[It] restricts [the] amount of time available for communicating to patients, families, and staff. For example, I would like to spend as much time as I felt needed informing patients/families with diagnoses, tests, etc, especially new diagnoses … but sometimes feel like I need to cut short the discussion as I “need to get out” or “finish my work”—though I feel this is part of my work.

Another resident related this time constraint to difficulties in shared decision making:

It is harder to have as much time to speak with and really get to know patients, which impacts the ability to have shared decisions and understand patient perspectives.

In addition, many residents felt that the increased number of hand-offs from physician to physician had decreased the continuity of care for their patients. These transitions of care led many residents to feel that their colleagues were demonstrating less accountability to their patients and to one another. One resident described this as a:

Lost sense of accountability to patients and to each other (“I've got to go.”) Less sense of duty (“I'll just sign out my remaining work”).

Another resident argued that the current system of care—based on individual physician's “ownership” of particular patients—might not be structured appropriately for the new duty hour requirements:

I think the basic problem is that we've gone to an hourly system that would best suit a team-based approach, but we've held on to the ideals of autonomy and patient ownership (which I value highly). It makes it quite hard to get anything done in a short period of time, and I think compassion, empathy, and multiculturalism are probably the first things to go.

However, numerous residents felt that the duty hour requirements also promoted professionalism. In particular, a substantial number of residents linked decreased fatigue to a higher capacity for empathy, compassion, and sensitivity toward their patients and their colleagues. One resident wrote:

I think that residents feeling toxic leads to poor professionalism … grumpy, lack of sympathy, not wanting to take time for shared decisions with patients. Also makes it hard for learner excellence. Thus better rest → more professional behavior.

Another resident agreed:

We are better rested when our basic needs are met (rest, food, hygiene), and we are more empathic of our patients' needs.

Some residents acknowledged the tension between the potential reduction of professionalism due to duty hour requirements and the improvements to their own well-being. One resident wrote:

You are not able to see all patients through to the end and the patient is confused about primary care provider. But it has helped my life be at least livable.

Finally, some residents felt that the increased transitions of care actually led to improved teamwork and communication in patient care. One resident wrote:

[There is] increased communication between residents—increased handing over, therefore increased conversations and trust.

DISCUSSION

In our survey, residents endorsed the importance of the training and practice of the principles of professionalism as defined by the ABIM and ACGME.1,3 Residents' perceptions of current and preferred teaching methods reflect the importance of faculty and colleague role-modeling, the culture of professionalism within their institutions, and the importance of evaluation and feedback. All of these are part of the informal and hidden curriculum, which, our findings suggest, should be a focus for curricular interventions in this area.10,11

Although residents felt that most principles of professionalism were important, significantly fewer residents felt that these principles were easy to incorporate into their daily practice. Residents were less likely to feel that they could easily incorporate certain principles—conflicts of interest and self-awareness—into their daily practice than others. Some of the reasons for this gap between importance and ease of practice were reflected in their qualitative responses, which revealed challenges to putting professionalism principles into practice, particularly within the duty hour requirements. Residents cited time constraints as a primary barrier to incorporating professionalism into their daily lives. Residents also described how this time pressure actually intensified in the transition to duty hour implementation, leaving them feeling that they had even less time for communication and shared decision making with their patients and patients' families. Time constraints may be a particularly important barrier to teaching residents the skills for reflection, self-awareness, cultural sensitivity, and communication that are required to interact successfully with patients perceived as challenging or difficult.

The qualitative analysis revealed residents' struggles to reconcile how the duty hour requirements both reduced and promoted their ability to incorporate professionalism into their work. Residents appreciated that duty hour requirements reduced their fatigue and improved their own well-being, but they struggled with the tension this created in remaining altruistic toward patients and accountable to patients and colleagues. Some residents felt that these goals are congruent and that professional interactions with patients and colleagues are improved when their own well-being is maximized, a sentiment echoed in the medical literature.12 Others lamented the shift from “patient ownership” to a system of shiftwork and transitions of care in which residents feel less responsible for patients or less accountable to one another. Some acknowledged the shift to team responsibility, which could result in a broadened concept of individual, group, and institutional responsibility to patients and colleagues, particularly with respect to transitions in care.

Our results are consistent with previous studies about residents' attitudes toward professionalism. A Michigan study analyzing interns' essays about professional behavior revealed as the most salient issues for residents the conflict between altruism and self-interest and the management of difficult interpersonal interactions.7 In 1 Canadian survey, senior residents reported that they learned the most about professionalism by observing positive role models and interacting with patients.8 Our study adds further insights about the specific dilemmas in incorporating professionalism under the duty hour requirements.

Professionalism curricula may increase salience for learners by highlighting conflicts in professionalism that occur in daily practice and by guiding learners as they negotiate solutions to these conflicts.13 The data from our study suggest that professionalism curricula for residents could target such challenges as: managing time constraints, particularly under the duty hour requirements; understanding and negotiating with “challenging patients”; and balancing the need for personal well-being with the welfare of patients and accountability toward colleagues.

Our study has several strengths. The multi-institutional and multispecialty sample population improves the generalizability of our findings to other specialties and academic institutions. We designed our survey questions to maximize face and content validity, using literature searches, interviews with program directors, and pilot testing among medical educators to incorporate important topics within professionalism. In addition, our use of open-ended questions provided an opportunity to solicit the opinions of our respondents in their own words and allowed respondents to raise issues we may not have considered in designing our closed-ended survey questions. Our qualitative analysis validated and supplemented the findings of our quantitative analysis, highlighting the importance of role-modeling and providing deeper insights into the impact of the duty hour implementation.

Our study has several limitations as well. First, the response rate to the survey was only 54%, although this is comparable to response rates in mailed physician surveys.14 Postgraduate year 1 residents were more likely to respond than higher-level residents. This may account for the number of unanswered open-ended questions regarding duty hours, given PGY-1 residents' lack of prior experience for comparison. This may limit the validity of our sample as representative of all PGYs. Second, although this survey was targeted at multiple disciplines, our eligible sample included larger numbers of IM residents. Third, we lack information about the general validity and reliability of our questions. We did have experts in the field as well as recent residency graduates review the survey for content validity. In addition, our respondents confirmed the components of professionalism included in the survey, particularly in their open-ended responses. Fourth, we did not collect data regarding the actual compliance with duty hour requirements within each institution, and our data must be interpreted within the context of a transition toward multiple systems of duty hour compliance. Finally, our survey was designed to capture residents' perspectives about the formal and informal curricula and does not include the perspectives of others in the work environment—such as faculty, staff, or patients. Given our methodology, we lack objective data to confirm the actual curricula offered by the training programs, and residents' preferred learning styles do not necessarily include those methods that will be most effective.

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable data on residents' perceptions of the principles of professionalism and their importance, perceptions of how professionalism is taught, preferences regarding learning methods, and perceptions of what promotes and inhibits professionalism, including the impact of duty hour requirements. This information should be helpful to educators as they plan interventions to promote professionalism, building on the strengths of the informal curriculum within their programs and targeting such challenges as time constraints, communication with challenging patients, and continuity in the context of duty hour implementation. Future research is needed to confirm our findings, incorporate the perspectives of patients, staff and faculty, and investigate the effectiveness of interventions for promoting professionalism.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Eric Bass, Ken Kolodner, ScD, and the Johns Hopkins Bayview Faculty Development Program for assistance in this project. Funding for this project was provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Grant #5 D55HP00049-06-00, and the Innovative Curriculum Grant for Graduate Medical Education, Department of Graduate Medical Education, University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at www.blackwell-synergy.com

REFERENCES

- 1.ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine, ACP-ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blank L, Kimball H, et al. ABIM Foundation, ACP Foundation. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter 15 months later. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:839–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACGME. Chicago, IL: ACGME; 1999. [July 14, 2005]. ACGME Outcome Project. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp#5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACGME. Chicago, IL: ACGME; 2003. [July 14, 2005]. Resident duty hours and the working environment. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_Lang703.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larriviere D. Duty hours vs professional ethics: ACGME rules create conflicts. Neurology. 2004;63:E4–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.1.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Gadol AA, Piepgras DG, Krishnamurthy S, Fessler RD. Resident duty hours reform: results of a national survey of the program directors and residents in neurosurgery training programs. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:398. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000147999.64356.57. 403; discussion 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggly S, Brennan S, Wiese-Rometsch W. “Once when I was on call…,” theory versus reality in training for professionalism. Acad Med. 2005;80:371–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownell AK, Cote L. Senior residents' views on the meaning of professionalism and how they learn about it. Acad Med. 2001;76:734–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200107000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research: a multimethod typology and qualitative roadmap. In: Miller WL, Crabtree BF, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1999. pp. 21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees' ethical choices. Acad Med. 1996;71:624–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199606000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mareiniss DP. Decreasing GME training stress to foster residents' professionalism. Acad Med. 2004;79:825–31. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, et al. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(suppl. 10):S6–S11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:61–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.