Abstract

BACKGROUND

Historical undertreatment of pain among inpatients has resulted in a national requirement for pain practice standards.

OBJECTIVE

We hypothesized that adoption/promulgation of practice standards in January 2003 at 1 suburban teaching hospital progressively increased compliance with those standards and decreased pain.

DESIGN

We retrospectively reviewed medical records each month during 2003, when pain standards were adopted with repeated, institution-wide, and nursing-unit-based interventions. Also, we reviewed discharges during 1 month in adjacent years.

PATIENTS

We identified adult patients from 20 medical and surgical All-Payer Refined Disease Related Groupings (APRDRGs) in which opiate charges were most common in 2003. Among these, we considered patients actually receiving opiates and randomly chose equal numbers of matching subjects in each month of 2003. Matching was for APRDRG and complexity group. We also matched January 2003 discharges with those from January 2001, 2002, and 2004.

MEASUREMENTS

For each patient, we captured 3 variables measuring standards compliance: percentage pain observations reported numerically, number of observations, and median time to reassessment after opiates. We also captured 3 pain variables: median pain score, rate of improvement in pain score, and total opiates dispensed.

RESULTS

There were 360 qualifying discharges in 2003, and 75 in the other years. Numeric observations increased 15%, number of assessments 36%, and reassessment time decreased 60%. All changes were significant but occurred before standards implementation. Among pain measures, only rate of pain improvement changed, worsening slightly but significantly (−0.02 to −0.005 U/h), also before standards.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementation of pain practice standards affected neither practice nor pain.

Keywords: pain, hospital standards, nursing care, symptom management

Failure of physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals to measure and respond to their patients' pain has been convincingly documented over 3 decades.1–3 During the same period, paradoxically, discoveries in the pharmacology and physiology of pain have advanced more rapidly than at any time in the past.4–7 Recently, perhaps in part as a consequence of the growing palliative care movement, several leading health care organizations have espoused aggressive management of pain and offered protocols.8–11 This new emphasis on pain control has also found regulatory expression. In 2000, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health care Organizations (JCAHO) mandated adoption of policies for pain education, screening, follow-up, and uniform measurement, as well as for assuring implementation.12 These requirements apply now to every hospital and JCAHO-regulated outpatient facility in the country; however, there is little published evidence that adoption of pain management standards has led to their implementation or that their implementation has had an effect on the burden of pain.13–15

We applied retrospective measures of opiate use, pain intensity, and rate of improvement before and after introduction of pain management standards at our suburban teaching hospital. We also applied compliance measures of the extent to which these standards were implemented, choosing to measure implementation of those pain standards that were readily quantifiable and addressed individual patient care. This report therefore concerns the relationship at 1 institution between pain standards implementation and pain relief throughout the major adult inpatient services. Our hypothesis was that adoption and implementation of pain practice standards consistent with those prescribed by JCAHO resulted (over the succeeding 12 months) in all of the following: progressively improved compliance (measures of implementation), increasingly more rapid decline in pain scores after start of treatment, increased use of opiates, and a decline in average pain scores.

METHODS

Adoption of Pain Standards

Monmouth Medical Center is a suburban teaching hospital in central New Jersey with 550 licensed beds. In January 2003, the medical center inaugurated a program to implement pain management practice standards compliant with JCAHO requirements. Nurse educators and nursing members of the Quality Improvement team conducted teaching sessions on individual nursing stations, for each shift and repetitively throughout the year. Educational sessions focused on the following topics: (1) standards for uniform pain measurement, (2) required intervals for pain reassessment after intervention, (3) education of patients and families about the importance and possibility of pain relief and goal setting, and (4) dosage ranges and the pharmacology of opiates. In addition, a palliative care nurse practitioner conducted clinical case discussions with nursing staff on a monthly basis and oriented all newly hired clinical educators, clinical directors, and pharmacists.

Nurses and all new personnel were provided with a computer-based self-learning module addressing pain management. A pain management grand-round for both nurses and physicians was held in September 2003. At intervals during that year, the director of the Division of Palliative Care and Pain, a palliative care-trained physician, oriented house staff first as a group and then with lectures targeted separately to the medical, surgical, pediatric, and obstetric/gynecologic house officers. Virtually all patients in the medical center on these services are cared for by house staff. From the perspective of the attending physician, a 5-month series in lieu of medical grand rounds was completed in 2000, and a physician-led palliative care service was available from that time.

To facilitate standardization of pain documentation, new forms were introduced based on an 11-point numeric pain scale (0 to 10), consistent with the new policy. Management standards called for pain assessments at the time of admission and with every vital signs' evaluation. In addition, nurses were required to reassess pain 60 minutes after oral and 30 minutes after parenteral pain medication, and to inform the house officer or attending physician if there was no relief. The nursing education office distributed to all nursing units materials for posting that defined pain types, explained the use of a pain scale, provided a guide to cultural issues and specific techniques in pain assessment, and specified equianalgesic doses of pain medications. Compliance with the new policy was monitored by monthly pain documentation audits throughout the year with feedback to individual nurses.

Identification of Study Patients

This study was approved by the institutional review board, which granted a waiver from the Health Information Portability and Privacy Act requirement for individual consent before record review. Using a patient-level financial database (Trendstar, HBOC, Atlanta, GA), we identified the 10 surgical and 10 medical All-Payer Refined Disease Related Groupings (3M Health Information Systems, Salt Lake City, UT) at our institution in 2003 in which opiates were most commonly prescribed. All-Payer Refined Disease Related Groupings (APRDRGs) is a commonly used, proprietary risk stratification paradigm derived from Disease Related Groupings (DRGs) but applicable to non-Medicare patients and not used in billing. A computerized grouper assigns patients both to a (modified) DRG and to 1 of 4 levels of mortality risk and 4 levels of case complexity. This system, adopted by many individual states and by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, uses hospital administrative data limited to basic demographics, outcome of hospitalization, procedures performed, and comorbidities.16

We identified by month all patients above the age of 18 who were discharged in 1 of the 20 APRDRGs defined above. We then reduced this number to those patients who themselves had charges for opiates during their hospitalization. Among these patients, we noted the complexity value (1 to 4) associated with each case in the APRDRG complexity scoring system, and we captured gender, age, principal diagnosis and procedure, clinical service, and outcome of the hospitalization.

Matching Between Months of 2003

Complexity values were first dichotomized into simple (category 1 or 2) and complex (category 3 or 4). This was carried out for ease and to ensure larger study samples from which to select patients. We then counted the instances in each month of 2003 of every combination of APRDRG and its dichotomized complexity category. For combinations of APRDRG/complexity represented by 4 or more cases in each of the 12 months, we randomly chose 4 cases in each month. For combinations of APRDRG/complexity represented by 1 or more, but fewer than 4, cases in each month, we randomly chose 1 case in each month. Each month of 2003 contained, therefore, an equal number of patients and of APRDRG diagnostic and complexity categories. Both common and less common APRDRG/complexity categories were included in the sample, but as 4 patients were randomly selected from common categories, these were more heavily represented. Matching was accomplished by sorting patients and their diagnostic categories by month of discharge on a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, 1999). The vertical lookup, and random number functions were used to identify representation in all months and randomly choose patients.

Matching Between January 2003 and January 2001, 2002, and 2004

In addition, we wished to compare patient management and pain control across a 3-year period to determine whether any change had occurred independent of the implementation program in 2003. We therefore matched patients discharged in January 2001, 2002, and 2004 for comparison with those discharged in January 2003.

Because APRDRG grouping was not available at our institution in 2001, we matched patients between years in a slightly different manner than we matched patients between months of 2003. For each patient already selected in January 2003, we matched in January of the other 3 years patients with the same DRG, gender, principal diagnosis (or principal procedure in surgical DRGs), and outcome of hospitalization (categories were “home,” “expired,” and transfer to “acute,” “subacute,” or “chronic” care). We matched for outcome because we suspected that a patient's severe disability or imminent death might have a significant influence on opiate prescription and dispensing. When more than 1 patient could be matched in this manner, we selected the patient closest in age to the reference patient from January 2003. Matching between years was accomplished by listing 2003 cases horizontally on the Excel spreadsheet and using the vertical lookup and if-then functionality of the spreadsheet to identify matches between their characteristics and those of vertically listed discharges in the relevant years. If all 30 patients from January 2003 could not be matched in another year, we nevertheless included all January 2003 patients in comparisons across years.

Medical Record Review

After selection of potential cases, we excluded from further study patients found to have received only a single dose of opiates in the emergency department. We included adult patients on the wards, in the intensive care units, and those who were receiving comfort care only. We reviewed the medical record, noting time, dose, and route of all opiates dispensed (including those via patient-controlled intravenous or epidural pumps) during the first 72 hours after an initial dose of opiate (medical cases) or during the first 72 hours after surgery (surgical, orthopedic, and obstetric cases).

In aggregating data, we expressed all opiate doses as equivalents of 1 mg morphine sulfate given intravenously, using a conversion table published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service's Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, now the Agency for Health care Quality and Research.17 In addition, we reviewed nurses' and physicians' progress notes to determine the time and results of all pain assessments made during the same 72 hours in which we recorded dispensing of pain medication. Pain assessments that were recorded as numbers were captured in this form. Those expressed in words were translated into numbers according to an equivalency scale published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.18 We did not attempt to establish the technique used in eliciting patient responses.

From these data, we calculated 3 compliance measures for each patient during the first 72 hours of pain management: percentage of pain observations reported numerically rather than descriptively, total number of pain assessments, and average time to pain reassessment after opiate dispensing. We also calculated 3 pain control measures: average pain score, total dose of morphine equivalents dispensed, and the average hourly rate of change in pain. The average rate of change was calculated as the least squares linear regression of all points determined by a pain score and the time it was entered during the first 72 hours of pain management. Medical records were reviewed by 2 authors (S.N. and C.V.), who also rereviewed each other's analysis of every 10th chart until, after 100 charts, it became clear that agreement was nearly complete.

ANALYSIS

We generated frequency distributions of demographic information and diagnostic category to characterize study patients. Graphic display and summary statistics were also produced for the 3 implementation measures and the 3 pain control measures. None of these 6 measures appeared to be normally distributed; we therefore used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to calculate significance of differences in all outcome measures between patients discharged before and after the intervention, that is, in January 2001 or 2002, compared with January 2003 or 2004. We also applied least squares simple linear regression analysis to describe the degree of linearity between each outcome and time during successive months in 2003. We calculated 2-sided P values and, for regressions, R2 values.

RESULTS

From 14,313 patients discharged in 2003, we identified 2,412 patients with charges for opiates in the 10 surgical and the 10 medical APRDRGs that were most often associated with charges for opiates. Among these, we selected 408 (17%) for medical record review using the criteria described above. Of selected patients, 52 had only a single dose of opiates in the emergency department, leaving 360 (15%) for study. Thirty of the 360 patients were discharged in January and 30 in every other month of 2003. The 30 patients discharged in January 2003 could be matched with 26 patients in 2001, 25 in 2002, and 24 in 2004 using the criteria described above. The characteristics of study patients are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Patients

| 2003 Patients (360) | 2001 Patients (26) | 2002 Patients (25) | 2004 Patients (24) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Male | 124 | 34 | 5 | 19 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 24 |

| DRG | ||||||||

| 89 | 24 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 5 |

| 124 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 125 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 127 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 143 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 148 | 24 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 182 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 183 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 204 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 209 | 72 | 20 | 5 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 24 |

| 288 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 370 | 20 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 371 | 40 | 11 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 19 |

| 373 | 48 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 19 |

| 395 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 498 | 48 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 14 |

| Severity | ||||||||

| Low | 300 | 83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| High | 60 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Age | ||||||||

| 20–40 | 150 | 42 | 11 | 42 | 10 | 48 | 11 | 52 |

| 41–60 | 99 | 28 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 24 |

| 61–80 | 87 | 24 | 8 | 31 | 6 | 29 | 6 | 29 |

| 81 or > | 25 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Admission month | ||||||||

| Jan | 30 | 8 | 20 | 77 | 18 | 76 | 20 | 83 |

| Feb | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apr | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jun | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jul | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aug | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sep | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oct | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov | 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec | 30 | 8 | 6 | 23 | 7 | 24 | 4 | 17 |

| Clinical service | ||||||||

| ObGyn | 104 | 29 | 9 | 35 | 9 | 33 | 8 | 33 |

| Medicine | 91 | 25 | 7 | 27 | 7 | 33 | 9 | 38 |

| Ortho | 116 | 32 | 9 | 35 | 8 | 29 | 6 | 25 |

| Surgery | 47 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Psych | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peds | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain observations | ||||||||

| Numeric | 4,430 | 90 | 160 | 68 | 166 | 76 | 283 | 93 |

| Verbal | 476 | 10 | 75 | 32 | 46 | 24 | 21 | 7 |

DRG, Disease Related Groupings; NA, not applicable.

Fourteen different APRDRGs and 18 combinations of APRDRG and complexity were represented among the 360 Study patients discharged in 2003.

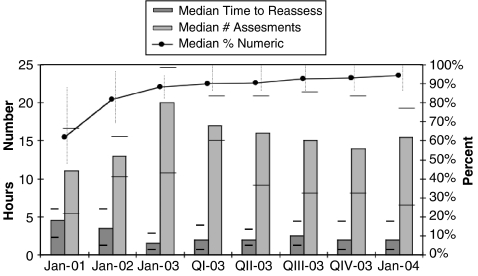

Figure 1 displays compliance measures for all patients by month and year of discharge. The median percentage numeric observations increased from 77% among patients discharged during January, 2001 and 2002 to 92% in January of the following 2 years (P < 0.001). The median total number of assessments also improved significantly, from 12.5 to 17.0 (P = 0.05), as did the median time to reassessment after opiate dosing (from 4.2 to 1.7 hours, P = 0.04). The figure also demonstrates that almost all change occurred not during or following the 2003 program to implement pain practice standards, but in the preceding year.

FIGURE 1.

Median compliance measures in January of 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and by quarter in 2003. Interquartile ranges are shown.

Least squares regression for compliance measures during 2003 showed little or no change with month. There was very weak but statistically significant linearity between median percentage numeric observations and month (slope = 0.51, P = 0.05, R2 = 0.012). The median total observations did not change significantly during 2003 (slope = −0.27, P = 0.07, R2 = 0.01). Nor did the median time to reassessment of pain (slope = 0.02, P = 0.77, R2 = 0.01).

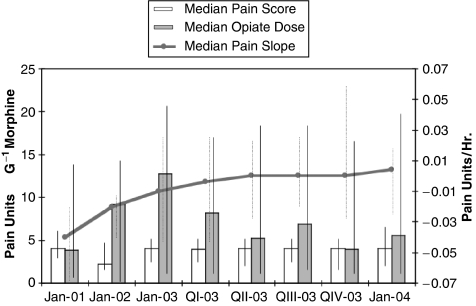

Pain reduction data are shown in Figure 2. There was no change in the average median pain score, or the median opiate dose among inpatients discharged during successive months of 2003, nor were there significant differences in these measures between patients discharged in January, 2001 and 2002 compared with those discharged in January, 2003 and 2004. Conversely, there was a small but significant decrease in the median monthly rate of improvement in pain (from −0.02 pain units per hour to −0.005 pain units per hour) from January, 2001 and 2002 to January, 2003 and 2004 (P = 0.02). The median rate of improvement in pain did not change significantly with time during 2003 (slope = −0.01, P = 0.29, R2 = 0.004).

FIGURE 2.

Median pain control measures in January of 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and by quarter in 2003. Interquartile ranges are shown.

DISCUSSION

We found that a 0 to 10 numeric pain score was largely adopted a year before the institution's educational program, presumably because of changes in professional nursing practice that had become widely known. A heightened local and national awareness of pain and its importance as “fifth vital sign” may also have contributed to the observed increase in average number of pain assessments and decrease in time to reassessment that occurred before, and entirely independent of, the institution's official adoption of pain practice standards. We considered it possible that changes not in awareness but in workload and case intensity during 2002 to 2003 may have led to the observed improvement in compliance measures. There were, however, no changes in nursing staffing on the floors of our institution. Moreover, the mean number of nursing–patient hours per registered nurse remained between 2 and 3 during the years of the study and the hospital's case mix index was stable at just over 1.0 during that period, suggesting that there was no net change in workload pressure.

Disappointingly, despite apparently rising professional awareness of the importance of pain management and despite adoption of standards with an aggressive implementation program, there were no favorable changes in pain by any of our 3 pain measures over the 3 years studied. The average change in pain (reduction in pain units each hour) actually became worse after adoption of pain standards, although the difference was negligible: a median decrease of 0.02 pain units per hour was observed during January, 2001 and 2002, with a slower median decrease −0.005 pain units per hour during January, 2003 and 2004. Possible explanations for the lack of a favorable pain response include unsuitability of our pain measures, intrinsic unreliability or inaccuracy of the 0 to 10 pain scale, and ineffectiveness of pain standards as they are currently understood by JCAHO and others.

This study must be interpreted with caution because of a number of important limitations. We report data from a single institution and from patients in only 14 APRDRGs. Although we matched a number of patient factors in selecting subjects for each study month, we could not match for all possible determinants of pain, raising the possibility of seasonal or other unnoticed bias. Nor could we readily evaluate in retrospect the rigor with which JCAHO-compliant standards were implemented in 2003 through in-service education and individual follow-up; more or less effective implementation might have given different results. Our conversion of verbal to numeric pain assessments was guided by an established paradigm, but if verbal description regularly under or overvalued numeric description, then pain may have actually increased or decreased with time (as verbal description became rarer), even though the score remained the same. We did not study implementation of all JCAHO guidelines, but limited ourselves to those we could measure numerically in individual patients. And finally, we could not as accurately determine median pain score or average rate of improvement in pain among patients with fewer data points owing to fewer pain assessments.

Despite these limitations, we think that our results are provocative. We found that formal introduction of JCAHO-compliant pain practice standards had virtually no effect on a practice that appeared to be independently evolving, perhaps as the result of a growing local and national palliative care influence. More disturbingly, we found that neither introduction of practice standards nor changes in practice that anticipated those standards had any favorable effect on patients' self-reported pain. Our study suggests that adopting regulations and implementing them, with the usual apparatus of in-service education, may not by itself improve control of pain. Specific strategies targeted to pain outcomes should be studied. Our results also suggest that regulatory requirements should be tested for clinical effectiveness by those with the authority to enforce them nationwide.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Martha Radford for critically reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marks RM, Sachar EJ. Undertreatement of medical inpatients with narcotic analgesics. Ann Intern Med. 1973;78:173–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-78-2-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu X, Belgrade MJ. Pain in hospitalized patients with medical illnesses. J Pain Symp Managet. 1993;8:17–21. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90115-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe J. Narcotics in the treatment of pain. Med Clin North Am. 1968;52:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasternak GW. Molecular biology of opioid analgesia. Pain Symp Manage. 2005;29(Suppl 5):S2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins LR, Mayer DJ. Organization of endogenous opiate and nonopiate pain control systems. Science. 1982;216:1185–92. doi: 10.1126/science.6281891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999;(Suppl 6):S121–6. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413:203–10. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice guidelines in oncology (Version 2. 2005) [October 17, 2005]; Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/pain.pdf.

- 9.Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer. JAMA. 1995;274: 1874–80 doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530230060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1573–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon DB, Dahl JL, Miaskowski C, et al. American pain society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1574–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Improving the quality of pain management through measurement and action. [February 12, 2006]; Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/news+room/health+care+issues/pain_mono_jc.pdf.

- 13.Frasco PE, Sprung J, Trentman TL. The impact of the joint commission for accreditation of healthcare organizations pain initiative on perioperative opiate consumption and recovery room length of stay. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:162–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000139354.26208.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vila H, Smith RA, Augustyniak MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of pain management before and after implementation of hospital-wide pain management standards: is patient safety compromised by treatment based solely on numerical pain ratings? Anesth Analg. 2005;101:474–80. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000155970.45321.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor S, Voytovich AE, Kozol RA. Has the pendulum swung too far in postoperative pain control? Am J Surg. 2003;186:472–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies SM, Geppert J, McClellan M, McDonald KM, Romano PS, Shojania KG. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. Refinement of the HCUP Quality Indicators. Technical Review No. 4. AHRQ Publication No. 01-0035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AHCPR clinical practice guideline: management of cancer pain. [February 12, 2006]; Table 11. Available at: http://www.painresearch.utah.edu/cancerpain/guidelineF.html.

- 18.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice guidelines in oncology (Version 2. 2005) [October 17, 2005];:11. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/pain.pdf.

- 19.SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC: SAS 9.00 (TS MO); 2000. [Google Scholar]