Abstract

Context

Little is known about the epidemiology of Intermittent Explosive Disorder.

Objective

To present nationally representative data on the prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV Intermittent Explosive Disorder.

Design

The WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used to assess DSM-IV anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders, and impulse-control disorders.

Setting

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), a face-to-face household survey carried out in 2001–03.

Participants

A nationally representative sample of 9282 people ages 18+

Main outcome variable

Diagnoses of DSM-IV Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED)

Results

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence estimates of DSM-IV IED are 7.3% and 3.9%., with a mean 43 lifetime attacks resulting in $1359 property damage. IED-related injuries occurred 180 times per 100 lifetime cases. Mean age of onset was 14. Socio-demographic correlates were uniformly weak. IED was significantly comorbid with most DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance disorders. Although the majority of people with IED (60.3%) obtained professional treatment for emotional or substance problems at some time in their life, only 28.8% ever received treatment for their anger, while only 11.7% of 12-month cases received treatment for their anger in the 12 months before interview.

Conclusions

IED is a much more common condition than previously recognized. The early age of onset, significant associations with comorbid mental disorders that have later ages of onset, and low proportion of cases in treatment all make IED a promising target for early detection, outreach, and treatment.

Keywords: Epidemiology, National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), as operationalized in DSM-IV, is characterized by recurrent episodes of serious assaultive acts that are out of proportion to psychosocial stressors and that are not better accounted for either by another mental disorder or by the physiological effects of a substance with psychotropic properties. Despite the fact that IED, or some version of this diagnosis, has always been included in the DSM, changes in criteria in the various editions over the years have resulted in relatively little being known about the incidence or prevalence of IED either in clinical samples or in the general population. In DSM-III, for example, IED could not be diagnosed in patients with generalized aggression or impulsivity. Given that most individuals with serious aggressive outbursts also have generalized aggression or impulsivity, this restriction resulted in a significant underestimation of the IED syndrome in DSM-III.1 While this problem was remedied in the DSM-IV, other uncertainties remain, such as the nature and threshold frequency of aggressive acts needed to meet criteria for a diagnosis of IED.

Only two published studies exist on the prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV IED.2, 3 One examined 1300 patients in a university faculty private practice and found a 3.1% prevalence of current IED.3 The other examined a non-probability sub-sample of 253 respondents in the Baltimore ECA Follow-Up study and found lifetime and one-month prevalence estimates of 4.0% and 1.6%.2 That study also found the small number of respondents who met criteria for IED to have an early age of onset (usually in childhood or adolescence), a persistent course, significant psychosocial impairment, and little treatment for problems associated with IED.

In the context of a growing recognition that violence is an important component of mental disorder and that IED is the DSM disorder most directly linked to impulsive violence, the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)4 included an assessment of DSM-IV IED. The current report presents initial NCS-R results concerning the prevalence and correlates of this disorder in the general population of the US.

METHODS

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative, face-to-face household survey (n = 9282) conducted between February 2001 and April 2003 using a multi-stage clustered area probability sampling design.5, 6 The response rate was 70.9%. Recruitment began with a letter and study fact brochure followed by an in-person interviewer visit in which study aims and procedures were explained and verbal informed consent was obtained. Respondents received $50 for participation. Consent was verbal rather than written in order to be consistent with the recruitment procedures in the baseline NCS7 for purposes of trending. The NCS-R recruitment and consent procedures were approved by human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

All respondents were administered a Part I diagnostic interview as described below, while a subset of 5692 respondents also received a Part II interview that assessed additional disorders and correlates. Part II respondents included all who met lifetime criteria for any Part I disorder plus a probability sample of other Part I respondents. The Part I sample was weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households and for differences in intensity of recruitment effort among hard-to-recruit cases. The Part II sample was additionally weighted for the higher selection probabilities of Part I respondents with a lifetime disorder. A final weight adjusted the sample to match the 2000 census population on the cross-classification of a number of geographic and socio-demographic variables. All analyses reported in this paper employ these weights. More complete information on the NCS-R sampling design and weighting is reported elsewhere.6

Diagnostic assessment

NCS-R diagnoses are based on Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),8 a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview that generates diagnoses according to both ICD-109 and DSM-IV10 criteria. DSM-IV criteria are used in the current report. The diagnoses include the three broad classes of disorder assessed in previous CIDI surveys (anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance disorders) plus a group of disorders that share a common feature of difficulties with impulse-control (intermittent explosive disorder and three retrospectively reported childhood-adolescent disorders – oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Diagnostic hierarchy rules and organic exclusion rules were used in making diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere,11 blind clinical re-interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)12 with a probability sub-sample of NCS-R respondents found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses based on the CIDI and the SCID for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders. CIDI diagnoses of impulse-control disorders were not validated because the SCID contains no assessment of these disorders.

DSM-IV Criterion A for IED requires “several discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses that result in serious assaultive acts or destruction of property.” This criterion was operationalized in the CIDI by requiring the respondent to report at least one of three types of anger attacks: (i) “when all of a sudden you lost control and broke or smashed something worth more than a few dollars;” (ii) “when all of a sudden you lost control and hit or tried to hurt someone;” and (iii) “when all of a sudden you lost control and threatened to hit or hurt someone.” Three or more lifetime attacks were required to operationalize the DSM-IV requirement of “several” attacks. We also created a narrow definition of lifetime IED that requires three attacks in the same year. Although this temporal clustering is not included in DSM-IV, there is precedent for its use in clinical studies of IED.2 Building on this distinction, 12-month prevalence was defined using three successively more stringent requirements. The broad definition required three lifetime attacks and at least one attack in the past 12 months. The intermediate definition required three lifetime attacks in the same year and at least one attack in the past 12 months. The narrow definition required three attacks in the past 12 months.

DSM-IV criterion B for IED requires that the aggressiveness is “grossly out of proportion to any precipitating psychosocial stressor”. This criterion was operationalized in the CIDI by requiring the respondent to report either that they “got a lot more angry than most people would have been in the same situation” or that the attacked occurred “without good reason” or that the attack occurred “in situations where most people would not have had an anger attack.”

DSM-IV criterion C for IED requires that the “aggressive episodes are not better accounted for by another mental disorder and are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition.” This criterion was only partially operationalized in the CIDI. Two sets of question asked if anger attacks usually occur either when respondents have been drinking or using drugs or when they are in an episode of being sad or depressed. Positive responses were followed with probes about whether the attacks ever occurred at times other than when the respondent is under the influence of alcohol or drugs or depressed. If not, the case was considered due to substance use disorder and/or depression. A third set of questions asked about organic causes as follows: “Anger attacks can sometimes be caused by physical illnesses such as epilepsy or a head injury or by the use of medications. Were your anger attacks ever caused by physical illness or medications?” Positive responses were followed with probes that inquired about the nature of the illness and/or medication and whether the respondent ever had attacks other than during the course of the illness or under the influence of the medication. If not, the case was considered due to an organic cause.

Although the CIDI did not include parallel questions that excluded respondents whose anger attacks occurred in the course of bipolar disorder (BPD), we imposed a post hoc rule to make this exclusion based on evidence that IED has a particularly strong relationship with BPD.13-15 This rule excluded cases from a diagnosis of IED if they met lifetime criteria for mania or hypomania, reported that the ages of onset and recency of their IED fell within the ages of onset and recency of their mania or hypomania, and reported that the number of years they experienced manic or hypomanic episodes was greater than or equal to the number of years they had anger attacks. This rule artificially rules out the possibility of comorbidity between IED and BPD. However, we judged this bias to be the lesser of two evils in comparison to the possibility of over-estimating the prevalence of IED by failing to exclude anger attacks due to BPD.

Other measures

Four other sets of measures are used in the current report: measures of onset and course of IED; measures of socio-demographic variables, measures of impairment associated with IED, and measures of treatment. The measures of onset and course are based on retrospective reports about age of onset, number of lifetime attacks, number of years with at least one attack, and questions about attacks in the 12 months before the interview.

The socio-demographic variables include age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44), sex, race-ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), education (0–11, 12, 13–15, 16+), marital status (married-cohabitating, previously married, never married), employment status (working, student, homemaker, retired, other), and urbanicity (central city, suburb, adjacent-rural area).

The assessment of impairment includes questions about lifetime impairment as well as impairment in the past 12 months. The lifetime questions ask about the financial value of all the things the respondent ever broke or damaged during an anger attack and the number of times either the respondent or someone else had to seek medical attention because of an injury caused by one of the respondent’s anger attacks. The 12-month questions ask the respondent to rate the extent to which his IED interfered with his life and activities in the worst month of the past year using the Sheehan Disability Scales.16 The latter are 0–10 visual analogue scales that ask how much a focal disorder interfered with home management, work, social life, and personal relationships using the response options none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10).

Part II respondents were asked whether they ever received treatment for “problems with your emotions or nerves or your use of alcohol or drugs" and, if so, treatment by each of a number of different professionals in a variety of treatment settings.17 For each positive response, follow-up questions were asked about most recent treatment. Responses were used to distinguish treatment in five sectors: psychiatrist, non-psychiatrist mental health specialist (e.g., psychologist), general medical (e.g., primary care doctor), human services (e.g., religious or spiritual advisor), and complementary-alternative medicine (CAM; e.g., massage therapist, self-help group). In addition, respondents who met criteria for IED were asked if they ever obtained professional treatment for their anger problems and, if so, whether they were in treatment in the past 12 months.

Analysis methods

Prevalence estimates were calculated using cross-tabulations. Cumulative lifetime age of onset curves were calculated using the actuarial method.18 Associations of IED with socio-demographic variables and comorbid DSM-IV disorders were examined using logistic regression analysis. Temporal priorities of IED in comparison to comorbid conditions were investigated by comparing individual level retrospective age of onset reports across disorders. Impairment and treatment were examined using analysis of variance. Significance tests were carried out using the Taylor series linearization method19 implemented in the SUDAAN software package20 to adjust for the weighting and clustering of the NCS-R data. Multivariate significance was evaluated using Wald χ2 tests based on Taylor series design-based coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated at the .05 level with two-sided tests.

RESULTS

Prevalence and onset

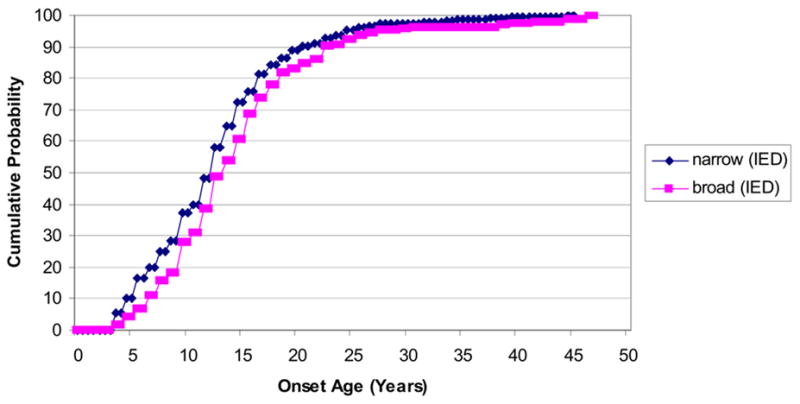

Lifetime prevalence estimates of broadly and narrowly defined IED (with standard errors in parentheses) are 7.3% (0.4) and 5.4% (0.3), respectively. Twelve-month prevalence estimates are 3.9% (0.3) using the broad definition, 3.5% (0.3) using the intermediate definition, and 2.7% (0.3) using the narrow definition. Mean age of onset (AOO) of first anger attack is in early adolescence for both narrowly defined lifetime cases (13.5) and for cases that meet only the broad lifetime definition (broad-only; 14.8; χ21 = 2.5, p = .12). The full AOO distributions are quite similar for narrow and broad-only lifetime cases. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Age of onset distributions of narrow and broad-only lifetime DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (n = 9282)

The majority of people with lifetime narrow (67.8%) and broad-only (71.2%) IED have a history of interpersonal violence during their anger attacks, while most others (20.9% narrow, 14.9% broad-only) have a history of threatening interpersonal violence during their attacks. Only a small minority of respondents (11.4% narrow, 13.9% broad-only) reported attacks that never included either interpersonal violence or threats of interpersonal violence.

Lifetime persistence and severity

Narrowly defined lifetime IED is significantly more persistent than broad-only IED. This can be seen indirectly by calculating the ratios of any 12-month anger attack to the lifetime prevalence estimates reported in the last section. These are 64.3% (2.7) for narrow and 24.3% (3.3) for broad-only lifetime IED (z = 9.0, p<.001). Higher persistence of narrow than broad-only cases can be seen more directly by comparing mean number of lifetime attacks (56.2 vs. 7.0; z = 7.8, p < .001), mean number of years with at least one attack (11.8 vs. 6.2; z = 8.5, p < .001), and highest number of attacks in a single year (27.8 vs. 1.6; z = 6.4, p < .001). (Table 1) Persistence is greatest among respondents whose attacks feature both interpersonal violence and property damage (e.g., an average of 59.7 lifetime attacks versus 24.4–30.2 in other sub-groups; F4, 620 = 6.8, p < .001). (More detailed results available on request.)

Table 1. Course and severity of lifetime DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder.

| Narrow1 | Broad-only1 | Broad1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | z | (p-value) | |

| I. Course | ||||||||

| Number of lifetime attacks | 56.2* | (6.3) | 7.0 | (0.5) | 43.6 | (4.4) | 7.8 | (<.001) |

| Number of years with attacks | 11.8* | (0.6) | 6.2 | (0.5) | 10.3 | (0.5) | 8.5 | (<.001) |

| Highest number of annual attacks | 27.8* | (4.1) | 1.6 | (0.1) | 21.1 | (2.8) | 6.4 | (<.001) |

| II. Severity | ||||||||

| Property damage ($)2 | 1602.7 | (134.9) | 447.2 | (135.3) | 1359.9 | (110.3) | 6.3 | (<.001) |

| Medical attention (per 100 cases)3 | 233.0 | (50.5) | 37.2 | (12.2) | 180.6 | (36.7) | 3.8 | (<.001) |

| (n) | (463) | (162) | (625) | |||||

Significant difference in means between the narrow and broad-only sub-samples at the .05 level, two-sided test

Narrow = three or more annual attacks in at least one year of life; Broad-only = three or more lifetime attacks without ever having as many as three attacks in a single year; Broad = Narrow or Broad-only.

Estimated cost of all the things ever damaged or broken in an anger attack.

Number of times during an anger attack someone was hurt bad enough to need medical attention per 100 cases of IED.

Narrow cases are also more severe, on average, than broad-only cases, as indicated both by a higher mean monetary value of objects damaged during anger attacks ($1602.7 vs. $447.2, z = 5.8, p < .001) and by in a higher mean number of times someone needed medical attention because of an anger attack (233.0 vs. 37.2 times per 100 cases; z = 3.8, p < .001). Severity, like persistence, is highest among respondents whose attacks feature both violence and property damage (e.g., an average of $1780 property damage versus $462-3 in other sub-groups that included property damage; F2, 622 = 37.6., p < .001; and an average of 180 instances of someone requiring medical attention per 100 cases versus 34–229 in other sub-groups that included violence; F2, 622 = 14.2, p = .001). (More detailed results available on request.) It is important to note, though, that these differences can be explained by frequency of attacks. Indeed, the mean value of lifetime property damage per attack is actually lower for narrow IED ($22) than for broad-only IED ($64). The same is true for injuries requiring medical attention (4.1 per 100 attacks for narrow IED and 5.3 for broad-only IED).

Twelve-month duration and role impairment

The average number of anger attacks in the past year is much higher for 12-month narrow (11.8) than intermediate-only (1.3) or broad-only (1.3) cases (F2,347 = 26.7, p <.001). (Table 2) Similar variation exists in number of weeks with an attack (F2,347 = 23.9, p <.001). Severe 12-month role impairment, as assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS), in comparison, varies much less across the three 12-month IED sub-samples. In fact, the proportion of 12-month cases reporting severe role impairment during the worst month of the year does not differ meaningfully across these sub-samples for three of the four SDS domains (F2, 347 = 1.7–3.2, p = .20–.44). The exception is the domain of interpersonal relationships, where severe impairment is considerably more common for narrow (27.5%) and intermediate-only (18.5%) than broad-only (13.1%) cases (F2, 347 = 7.7, p = .022).

Table 2. Duration and impairment of twelve-month DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder.

| Narrow1 | Intermediate-only1 | Broad-only1 | Broad1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | F2,347 | (p-value) | |

| I. Twelve-month persistence | ||||||||||

| Number of 12-month attacks | 11.8* | (1.4) | 1.3 | (0.1) | 1.3 | (0.1) | 8.5 | (0.9) | 26.7 | (<.001) |

| Number of weeks with attacks | 19.6* | (2.8) | 1.5 | (0.1) | 1.3 | (0.1) | 13.9 | (1.9) | 23.9 | (<.001) |

| II. Severe role impairment (Sheehan Disability Scales) | ||||||||||

| Home | 14.8 | (2.6) | 10.9 | (3.7) | 4.9 | (3.3) | 12.9 | (1.9) | 3.2 | (.20) |

| Work | 11.7 | (2.6) | 12.2 | (3.9) | 5.6 | (3.2) | 11.1 | (2.2) | 1.7 | (.44) |

| Interpersonal | 27.5* | (3.8) | 18.5 | (4.7) | 13.1 | (5.0) | 24.1 | (3.1) | 7.7 | (.022) |

| Social | 22.2 | (3.5) | 17.2 | (4.4) | 14.9 | (5.1) | 20.4 | (2.8) | 1.9 | (.38) |

| Summary | 40.4* | (3.6) | 25.8 | (4.7) | 19.6 | (6.5) | 35.1 | (2.9) | 11.4 | (.003) |

| (n) | (230) | (71) | (49) | (350) | ||||||

Significant difference in prevalence across the narrow, intermediate-only, and broad-only sub-samples at the .05 level, two-sided test

Narrow = three or more 12-month attacks; Intermediate-only = lifetime narrow and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad-only = lifetime broad and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad = Narrow or Intermediate-only or Broad-only.

Socio-demographic correlates

Statistically significant socio-demographic correlates of broadly defined lifetime IED include male, young, “other” race-ethnicity (i.e., not Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, or Hispanic), low education, married, not retired, not a homemaker, and low family income. The odds-ratios (ORs) for these socio-demographic correlates are mostly modest in magnitude (1.5–2.0), with the exception of age (1.6–43), where the contrast category of respondents ages 60+ has a very low reported prevalence (2.1%). (Table 2) Among respondents who meet broad lifetime criteria for IED, none of these socio-demographic variables distinguishes narrow from broad-only cases. No significant socio-demographic correlates were found for 12-month persistence among lifetime cases. (Results available on request.) Nor were meaningful socio-demographic correlates found that distinguished narrow 12-month IED from intermediate-only or broad-only cases. (Results available on request.)

Comorbidity

The vast majority (81.8%) of respondents with lifetime broad IED meet criteria for at least one of the other lifetime DSM-IV disorders assessed in the NCS-R. (Table 4) Indeed, broad lifetime IED is significantly and positively related to each of these other disorders after controlling for age, sex, and race-ethnicity, with ORs in the range 2.4–3.6. The ORs involving narrow IED are consistently higher than those involving broad-only IED, but the ratios of these two ORs are elevated only modestly for mood disorders (1.2–1.3) and most anxiety disorders (1.0–1.7). The ratios are more substantially elevated, in comparison, with generalized anxiety disorder (2.1), all the impulse-control disorders (1.9–2.6), and alcohol abuse (2.6).

Table 4. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder with other DSM-IV disorders.

| Broad1 | Narrow1: Broad-only1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I. Mood disornders | ||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 37.3 | (2.3) | 2.8* | (2.2–3.6) | 37.9 | (2.7) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.1) |

| Dysthymia | 9.7 | (1.5) | 3.2* | (2.3–4.5) | 10.0 | (1.8) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.7) |

| Any mood disorder | 37.4 | (2.2) | 2.8* | (2.2–3.5) | 38.1 | (2.6) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.2) |

| II. Anxiety disorders | ||||||||

| Agoraphobia | 6.5 | (1.1) | 3.4* | (2.3–5.1) | 6.8 | (1.3) | 1.3 | (0.6–3.1) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 18.7 | (1.8) | 3.6* | (2.8–4.7) | 20.7 | (2.3) | 2.1* | (1.3–3.2) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 4.4 | (1.5) | 2.5* | (1.1–5.7) | 4.5 | (1.9) | 1.1 | (0.2–6.9) |

| Panic disorder | 11.9 | (1.6) | 3.3* | (2.2–4.8) | 12.7 | (1.8) | 1.5 | (0.8–2.6) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 15.2 | (1.5) | 3.0* | (2.3–4.1) | 16.6 | (2.0) | 1.7 | (0.9–3.2) |

| Social phobia | 28.3 | (1.5) | 3.1* | (2.5–3.7) | 29.3 | (1.9) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) |

| Specific phobia | 24.0 | (1.9) | 2.4* | (2.0–3.0) | 25.9 | (2.4) | 1.6 | (1.0–2.7) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 10.5 | (1.1) | 2.9* | (2.2–4.0) | 10.5 | (1.4) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.8) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 58.1 | (1.9) | 3.8* | (3.1–4.6) | 60.2 | (2.4) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.3) |

| III. Impulse-control disorders | ||||||||

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 24.6 | (2.2) | 3.4* | (2.5–4.6) | 27.4 | (2.8) | 1.9* | (1.1–3.5) |

| Conduct disorder | 24.2 | (2.6) | 3.5* | (2.7–4.6) | 27.2 | (3.1) | 2.0* | (1.1–3.5) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 19.6 | (2.0) | 3.3* | (2.5–4.4) | 22.5 | (2.6) | 2.6* | (1.3–4.9) |

| Any impulse-control disorder | 44.9 | (2.2) | 4.1* | (3.3–5.0) | 49.5 | (2.8) | 2.1* | (1.2–3.7) |

| IV. Substance use disorders | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 32.9 | (3.0) | 3.1* | (2.3–4.1) | 37.5 | (3.8) | 2.6* | (1.7–4.2) |

| Alcohol dependence with abuse | 17.0 | (2.0) | 3.6* | (2.5–5.0) | 18.6 | (2.5) | 1.6 | (1.0–2.7) |

| Drug abuse | 21.8 | (2.3) | 2.7* | (2.0–3.6) | 23.6 | (3.1) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.7) |

| Drug dependence with abuse | 10.5 | (1.4) | 3.4* | (2.3–5.0) | 11.4 | (1.8) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.2) |

| Any substance disorder | 35.1 | (2.9) | 2.9* | (2.2–3.9) | 39.6 | (3.7) | 2.4* | (1.5–3.8) |

| V. Any disorder | ||||||||

| At least one disorder | 81.8 | (2.0) | 5.6* | (4.1–7.5) | 84.3 | (2.3) | 1.8* | (1.1–3.0) |

| Exactly one disorder | 16.1 | (1.4) | 0.8 | (0.7–1.0) | 14.1 | (1.4) | 0.6 | (0.3–0.9) |

| Exactly two disorders | 17.4 | (1.6) | 1.9* | (1.4–2.4) | 17.2 | (2.0) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) |

| Three or more disorders | 48.3 | (2.5) | 4.7* | (3.6–6.0) | 53.0 | (3.1) | 2.3* | (1.4–3.6) |

| (n) | (5692) | (625) | ||||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test, controlling for age, sex, and race-ethnicity

Narrow = three or more annual attacks in at least one year of life; Broad-only = three or more lifetime attacks without ever having as many as three attacks in a single year; Broad = Narrow or Broad-only.

We also examined comorbidity of 12-month IED with other 12-month DSM-IV disorders among respondents with a lifetime history of both disorders in the pair. Sparse data made it necessary to focus on broad disorder classes (i.e., any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder). As with lifetime comorbidity, ORs involving broad IED were meaningfully elevated (mood 2.7, anxiety 2.2, substance 2.2), while the ORs involving intermediate-only and narrow IED were generally similar in magnitude to those of broad IED. (Results available on request.)

Treatment

Although a majority (60.3%) of respondents with broad lifetime IED received treatment for emotional problems at some time in their life, only a minority (28.8%) were ever treated specifically for IED. (Table 5) Probabilities of receiving treatment overall as well as within particular services sectors did not differ significantly depending on broad versus narrow diagnostic criteria. One-third (33.6%) of respondents with broad 12-month IED received treatment for emotional problems in the year before interview, but only one-third of that number (11.7% of all 12-month cases) received treatment specifically for IED. As with lifetime treatment, probabilities of overall and sector-specific 12-month treatment did not differ significantly across cases that met broad, intermediate, or narrow diagnostic criteria.

Table 5. Lifetime and 12-month treatment of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder.

| Narrow1 | Broad-only1 | Broad1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Lifetime | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | F1,623 | (p-value) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 30.4 | (2.5) | 22.3 | (3.9) | 28.3 | (2.4) | 3.7 | (.06) | ||

| Other mental health specialist | 28.5 | (2.1) | 26.2 | (3.4) | 27.9 | (1.7) | 0.3 | (.59) | ||

| General medical | 27.4 | (2.2) | 25.9 | (3.9) | 27.0 | (1.8) | 0.1 | (.75) | ||

| Human services | 17.4 | (2.2) | 13.9 | (3.3) | 16.5 | (2.0) | 0.8 | (.39) | ||

| CAM | 18.1 | (1.9) | 15.2 | (2.8) | 17.4 | (1.7) | 0.8 | (.38) | ||

| Any treatment | 61.6 | (2.4) | 56.5 | (4.5) | 60.3 | (2.3) | 1.2 | (.27) | ||

| Any treatment for IED | 32.4* | (1.8) | 18.3 | (3.3) | 28.8 | (1.8) | 12.4 | (.001) | ||

| (n) | (463) | (162) | (625) | |||||||

| Narrow2 | Intermediate-only2 | Broad-only2 | Broad2 | |||||||

| II. Twelve-month | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | F2,347 | (p-value) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Psychiatrist | 9.5 | (2.0) | 10.9 | (4.1) | 6.7 | (3.1) | 9.5 | (1.7) | 0.4 | (.68) |

| Other mental health specialist | 12.5 | (2.0) | 7.4 | (3.2) | 12.4 | (4.7) | 11.4 | (1.7) | 0.7 | (.51) |

| General medical | 15.8 | (3.2) | 10.2 | (3.1) | 22.4 | (6.1) | 15.5 | (2.3) | 1.6 | (.21) |

| Human services | 6.7 | (2.3) | 8.3 | (3.7) | 12.4 | (5.4) | 7.7 | (1.9) | 0.6 | (.55) |

| CAM | 3.6 | (1.2) | 3.7 | (2.2) | 5.2 | (3.4) | 3.8 | (1.1) | 0.2 | (.85) |

| Any treatment | 33.2 | (3.7) | 31.2 | (6.1) | 40.4 | (7.2) | 33.6 | (2.7) | 0.5 | (.61) |

| Any treatment for IED | 13.2 | (2.1) | 7.7 | (3.1) | 10.0 | (4.4) | 11.7 | (1.8) | 1.3 | (.29) |

| (n) | (230) | (71) | (49) | (350) | ||||||

Significant difference in prevalence across the narrow, intermediate-only, and broad-only sub-samples at the .05 level, two-sided test

Narrow = three or more 12-month attacks; Intermediate-only = lifetime narrow and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad-only = lifetime broad and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad = Narrow or Broad-only.

Narrow = three or more 12-month attacks; Intermediate-only = lifetime narrow and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad-only = lifetime broad and one or two 12-month attacks; Broad = Narrow or Intermediate-only or Broad-only.

COMMENT

There are two noteworthy limitations of the data analyzed here. First, the diagnoses were based on fully structured lay interviews for which no information is available either on test-retest reliability or validity. Second, estimates of onset and course were based on retrospective rather than prospective reports. A limitation of the data analysis is that many separate significance tests were computed, introducing the possibility of some false positive associations. Caution is consequently needed in interpreting results prior to independent replication.

Within the context of these limitations, DSM-IV IED was estimated to be a fairly common disorder, with lifetime prevalence of 5.4–7.3% and 12-month prevalence of 2.7–3.9% (equivalent to approximately 11.5–16.0 million lifetime cases and 5.9–8.5 million 12-month cases in the US). These prevalence estimates are somewhat higher than those found in the two previously published studies of DSM-IV IED.2, 3 The Baltimore ECA study findings suggest that prevalence would have been roughly 25% higher if we had also included cases that met research criteria for IED.1 The latter extend the definition of IED to include recurrent aggressive outbursts that do not rise to the level examined in this study (e.g., verbal aggression against others in the absence of either threats or physical aggression against people or objects). As the latter behaviors are significantly impairing and have been shown to respond to psychopharmacologic treatment,21 a rationale exists for including them in the definition of IED in DSM-V.

Although we found a number of socio-demographic correlates of IED, these associations are modest in substantive terms. As an indication of this fact, the Pearson’s contingency coefficient, a generalization of the phi coefficient for polychotomous predictors,22 is only in the range .04–.05 for the significant socio-demographic correlates of lifetime broad IED. This means that IED is very widely distributed in the population rather than concentrated in any one segment of society.

We also found that IED usually begins in childhood or adolescence, that it is quite persistent over the life course (averages of 6.2–11.8 years with attacks), that it is associated with substantial role impairment, and that it has high comorbidity with other DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Although these NCS-R results cannot legitimately be compared with the results obtained in previous studies of patient samples, it is worth noting that similar patterns have consistently been found in clinical studies using mostly older diagnostic criteria.1, 23-27

As described in the section on measures, explicit questions to exclude anger attacks due to substance use disorders and major depression were included in the CIDI and a post hoc exclusion was made for bipolar disorder. As McElroy et al.13 found that some patients with comorbid IED and bipolar disorder have anger attacks when they are not in manic or hypomanic episodes, our blanket exclusion of cases with comorbid bipolar disorder underestimated the prevalence of IED. We did not make comparable exclusions of comorbid impulse-control disorders stipulated in DSM-IV as exclusions for IED (oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) based on the fact that DSM-IV says that an additional diagnosis of IED is warranted in the presence of “discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses.” An observation indirectly supporting this decision is that IED was reported to be much more persistent than comorbid impulse-control disorders.

DSM-IV also excludes anger attacks due to antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder). The NCS-R did not include a core assessment of Axis II disorders, making it impossible to consider these exclusions. However, the Baltimore ECA study, which focused on personality disorders, found unexpectedly low proportions of respondents with IED who also met criteria for antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder,2 suggesting that the failure to exclude these cases in the NCS-R might not have had a major effect on results. DSM-IV also excludes anger attacks due to non-affective psychosis (NAP), but the estimated prevalence of NAP was so low in the NCS-R that this exclusion made no meaningful difference to the results reported here.28

In evaluating the NCS-R finding that IED is significantly comorbidity with a wide range of other DSM-IV disorders it is important to recognize that the CIDI is a fully structured instrument that cannot make the subtle distinctions made in clinical interviews. This means that comorbidity is probably over-estimated in the NCS-R. Importantly, the ORs of IED with other CIDI/DSM-IV disorders are not markedly higher than those among the other disorders themselves. Nonetheless, the documentation of comorbidity between CIDI and a wide range of other disorders is consistent with the finding that undiagnosed IED is common in clinical samples.29 Although such associations are more intuitive with other impulse-control disorders and substance use disorders that with anxiety or mood disorders, evidence exists in clinical studies of an association between violent behavior and such anxiety disorders as PTSD30 and OCD,31 while anecdotal reports link panic attacks to violent behavior.32 Clinical evidence of an association between violent behavior and depression is even stronger.33

The finding that the ORs of IED with impulse-control (3.3–3.5) and substance use (2.7–3.6) disorders were not higher than those with mood (2.8–3.2) and anxiety (2.4–3.6) disorders raises the possibility that IED may be as much related to affective instability and dysregulation as to problems with impulse control. This possibility is consistent with the observation that affective instability is a risk factor for impulsive self-injury and suicidal behavior.34 It also needs to be noted, though, that impulsivity itself is associated with neuroticism35 and is known to be a risk factor for depression,36 suggesting that the joint effects of impulsivity and affective instability on IED are likely to be complex.

The early age of onset of IED is an important finding with regard to comorbidity because it means that IED is temporally primary to many of the other DSM-IV disorders with which it is comorbid.37 Within-person analyses (detailed results available on request) found that this was especially true for major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and substance use disorders, where the vast majority of respondent reported that their IED began at an earlier age than these other disorders. This raises the possibility that IED might be either a risk factor or a risk marker for temporally secondary comorbid disorders.38 Consistent with this possibility, a recent family study showed that the offspring of depressed adults with anger attacks have higher delinquency and aggressive behavior than the children of depressed adults without anger attacks.39 This suggests that intermittent explosive behavior might emerge quite early in subjects at risk of the subsequent onset of mood disorders. However, we are aware of no systematic research on the possibility that IED is a risk marker for temporally secondary disorders. It is interesting to note in this regard that the one published study that examined the family aggregation of IED found high inter-generational continuity of the disorder independent of comorbid conditions,37 which means that common genetic factors are unlikely to account for the comorbidity of IED with other DSM disorders.

This last observation suggests that the association of IED with the later first onset of secondary comorbid disorders is unlikely to be due to common underlying genetic risk factors or to phenotypic factors that are under strong genetic control, such as an impulsive personality style. If IED is a causal risk factor, in comparison, it might promote secondary disorders by leading to divorce, financial difficulties, and stressful life experiences that promote secondary disorders. If this last scenario is correct, then the fact that so few people obtain treatment for IED becomes even more important than otherwise because it means that an opportunity is being missed to intervene in the disorder at a point in time when it might still be possible to prevent the onset of secondary disorders.

It is noteworthy that a detailed analysis of delays in seeking treatment for IED found that the minority of people with IED who obtain professional help for their anger attacks typically wait a decade or more after onset before first treatment contact.40 Given the differences in the typical age of onset of IED compared to temporally secondary comorbid disorders,41 this means that initial treatment usually occurs only after the onset of most temporally secondary disorders and that the focus of the treatment is probably on the comorbid disorders. This interpretation is consistent with the finding that the majority of people with IED were found to receive treatment for emotional problems at some time in their life, but not for their anger. It is not clear from this result whether the low treatment of anger is due to greater reluctance to seek professional help for anger than other emotional problems or due to failure to conceptualize anger as a mental health problem. Given that so many people with IED obtain treatment for other emotional problems, a question can also be raised why treating clinicians do not include anger as a focus of their treatment or if the anger problems of their patients with IED are not recognized. We have no data in the NCS-R to adjudicate among these possibilities.

Another issue of importance for diagnosis and treatment of IED relates to the distinction between broad and narrow definitions. The stipulation in DSM-IV that the presence of only three serious lifetime episodes of aggression may be sufficient to make the diagnosis of an aggression disorder is one of the few instances in which DSM-IV does not have a temporal clustering requirement (e.g., three episodes in one year). It is noteworthy in this regard that even though the most severe form of IED in our study (narrow) is much more persistent than its less severe form (broad-only), the two did not differ significantly in most measures of functional impairment. As such, these data raise questions as to when to treat individuals with IED. Prospective treatment data will be needed to resolve this uncertainty. A related question for future research is whether successful early detection, outreach, and treatment of IED would help prevent the onset of secondary comorbid disorders. Given the age of onset distribution of IED, early detection would most reasonably take place in schools and might well be an important addition to ongoing school-based violence prevention programs.42, 43

Table 3. Socio-demographic correlates of lifetime DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder.

| Broad1 | Narrow1 : Broad-only1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 9.3 | (0.7) | 1.7* | (1.3–2.1) | 74.1 | (3.5) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) |

| Female | 5.6 | (0.4) | 1.0 | -- | 74.7 | (2.1) | 1.0 | -- |

| χ21 (p-value) | 22.7 (<.001) | 0.1 (.72) | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 12.1 | (1.1) | 4.3* | (2.1–9.0) | 79.1 | (2.6) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.5) |

| 30–44 | 9.0 | (0.9) | 2.9* | (1.3–6.3) | 72.5 | (3.5) | 1.0 | (0.4–3.0) |

| 45–59 | 5.3 | (0.5) | 1.6* | (0.8–3.5) | 69.7 | (4.2) | 1.0 | (0.3–2.8) |

| 60+ | 2.1 | (0.4) | 1.0 | -- | 69.8 | (7.3) | 1.0 | -- |

| χ23 (p-value) | 44.8 (<.001) | 3.4 (.33) | ||||||

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.8 | (1.0) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.2) | 74.4 | (4.5) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 6.8 | (0.5) | 1.0 | -- | 73.8 | (2.7) | 1.0 | -- |

| Hispanic | 9.3 | (1.2) | 0.9 | (0.7–1.3) | 76.5 | (4.9) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.7) |

| Other | 13.5 | (2.6) | 1.9 | (1.2–3.0) | 74.8 | (6.3) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.9) |

| χ23 (p-value) | 14.0 (.003) | 0.2 (.98) | ||||||

| Education (years) | ||||||||

| 0–11 | 9.4 | (1.0) | 2.0* | (1.4–3.0) | 82.8 | (3.6) | 2.1 | (1.0–4.6) |

| 12 | 6.9 | (0.7) | 1.4* | (1.0–1.8) | 73.9 | (4.2) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.8) |

| 13–15 | 8.5 | (0.9) | 1.6* | (1.2–2.2) | 73.5 | (4.2) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.5) |

| 16+ | 5.0 | (0.5) | 1.0 | -- | 73.5 | (5.5) | 1.0 | -- |

| χ23 (p-value) | 17.2 (.001) | 4.2 (.24) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Never married | 9.6 | (1.1) | 0.7* | (0.5–0.9) | 76.4 | (3.4) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.5) |

| Previously married | 5.0 | (0.5) | 0.8* | (0.7–1.0) | 76.5 | (4.8) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.3) |

| Married-cohabitating | 7.2 | (0.4) | 1.0 | -- | 72.6 | (3.1) | 1.0 | -- |

| χ22 (p-value) | 9.1 (.011) | 0.5 (.79) | ||||||

| Occupational status | ||||||||

| Employed | 8.2 | (0.5) | 1.0 | -- | 73.0 | (2.3) | 1.0 | -- |

| Student | 9.2 | (4.1) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.2) | 76.0 | (7.7) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.9) |

| Homemaker | 4.5 | (1.1) | 0.6* | (0.4–1.0) | 89.0 | (6.4) | 2.9 | (0.7–12.8) |

| Retired | 1.5 | (0.4) | 0.4* | (0.2–0.8) | 57.1 | (12.4) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.1) |

| Other | 11.0 | (1.5) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 81.5 | (4.3) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.7) |

| χ24 (p-value) | 15.9 (.003) | 3.2 (.52) | ||||||

| Family income | ||||||||

| Low | 8.7 | (0.9) | 1.5* | (1.1–2.0) | 80.0 | (3.5) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.4) |

| Low-average | 7.4 | (0.8) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 74.9 | (2.9) | 1.1 | (0.5–2.3) |

| High-average | 7.7 | (0.5) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.8) | 73.6 | (3.9) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.3) |

| High | 5.5 | (0.7) | 1.0 | -- | 67.0 | (5.8) | 1.0 | -- |

| χ23 (p-value) | 8.0 (.045) | 1.7 (.64) | ||||||

| Urbanicity | ||||||||

| Major metropolitan city | 6.2 | (0.7) | 1.0 | -- | 79.6 | (4.3) | 1.0 | -- |

| Other city | 8.3 | (1.1) | 1.4 | (1.0–2.1) | 68.6 | (6.4) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.2) |

| Major metropolitan suburb | 7.3 | (0.9) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.8) | 73.5 | (3.4) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.6) |

| Other suburb | 8.4 | (0.8) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.1) | 71.4 | (4.5) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.4) |

| Non-MSA | 6.8 | (0.6) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.7) | 77.2 | (4.2) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.9) |

| χ24 (p-value) | 6.0 (.20) | 3.8 (.44) | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||||

| χ2 | 456.4 (<.001) | 55.8 (<.001) | ||||||

| (n) | (5692) | (625) | ||||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Narrow = three or more annual attacks in at least one year of life; Broad-only = three or more lifetime attacks without ever having as many as three attacks in a single year; Broad = Narrow or Broad-only.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by NIMH (U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (New York State Psychiatric Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry; Technical University of Dresden). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. Send correspondence to ncs@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

References

- 1.Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Berman ME, Lish JD. Intermittent explosive disorder-revised: development, reliability, and validity of research criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:368–376. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coccaro EF, Schmidt CA, Samuels JF, Nestadt G. Lifetime and 1-month prevalence rates of intermittent explosive disorder in a community sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:820–824. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Anger and aggression in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:665–672. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington DC; APA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, Howes MJ, Jin R, Vega WA, Walters EE, Wang P, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, Beckman DA, Taylor P, Jr, Keck PE., Jr DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder: a report of 27 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:203–210. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0411. quiz 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElroy SL. Recognition and treatment of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 (Suppl 15):12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlis RH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS. The prevalence and clinical correlates of anger attacks during depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;79:291–295. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the U.S.: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halli SS, Rao KV, Halli SS. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis, Version 8.01 [computer program] Research Triangle Park, N.C: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ. Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality-disordered subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1081–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agresti A. Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monopolis S, Lion JR. Problems in the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1200–1202. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.9.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felthous AR, Bryant SG, Wingerter CB, Barratt E. The diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder in violent men. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lejoyeux M, Feuche N, Loi S, Solomon J, Ades J. Study of impulse-control disorders among alcohol-dependent patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:302–305. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Principal and additional DSM-IV disorders for which outpatients seek treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1299–1304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.10.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IR, Gagnon E, Guyer M, Howes MJ, Kendler KS, Shi L, Walters E, Wu EQ. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Biol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coccaro EF, Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Prevalence and features of intermittent explosive disorder in a clinical setting. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1003. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glenn DM, Beckham JC, Feldman ME, Kirby AC, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD. Violence and hostility among families of Vietnam veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence Vict. 2002;17:473–489. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.4.473.33685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayerovitch JI, du Fort GG, Kakuma R, Bland RC, Newman SC, Pinard G. Treatment seeking for obsessive-compulsive disorder: role of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:162–168. doi: 10.1053/comp.2003.50005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korn ML, Kotler M, Molcho A, Botsis AJ, Grosz D, Chen C, Plutchik R, Brown SL, van Praag HM. Suicide and violence associated with panic attacks. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:607–612. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90247-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knox M, King C, Hanna GL, Logan D, Ghaziuddin N. Aggressive behavior in clinically depressed adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:611–618. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Zanarini MC, Morey LC. Borderline personality disorder criteria associated with prospectively observed suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1296–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corruble E, Hatem N, Damy C, Falissard B, Guelfi JD, Reynaud M, Hardy P. Defense styles, impulsivity and suicide attempts in major depression. Psychopathology. 2003;36:279–284. doi: 10.1159/000075185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fava M, Kendler KS. Major depressive disorder. Neuron. 2000;28:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder: taming temper tantrums in the volatile impulsive adult. Current Psychiatry-Online. 2003:2. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alpert JE, Petersen T, Roffi PA, Papakostas GI, Freed R, Smith MM, Spector AR, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M. Behavioral and emotional disturbances in the offspring of depressed parents with anger attacks. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:102–106. doi: 10.1159/000068682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer G, Roberto AJ, Boster FJ, Roberto HL. Assessing the Get Real about Violence curriculum: process and outcome evaluation results and implications. Health Commun. 2004;16:451–474. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1604_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]