Abstract

We describe the case of a 43-year-old woman with transient ischemic neurologic deficits and recurrent systemic and pulmonary emboli in whom infectious work-up and extensive thrombophilic evaluation were unremarkable. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) established the diagnosis of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE). This is a rare condition often associated with hypercoagulable states or advanced malignancy such as adenocarcinomas, characterized by cardiac vegetations along valvular coaptation lines without destruction of leaflets. In our patient, we diagnosed an ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma, a malignant disorder that has been rarely reported in association with NBTE. This case illustrates that NBTE can present as an atypical manifestation of malignancy and must be distinguished from infective endocarditis, which implies a different therapeutic strategy. When confronted with findings of NBTE without a clear etiology, an occult neoplasm must be excluded. Anticoagulant therapy is the mainstay of treatment. However, cardiac vegetations may require surgical intervention in rare instances.

Keywords: nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, valvular vegetations, ovarian adenocarcinoma, malignancy

Thromboembolism associated with malignancy was first described by Trousseau in 1865, as “migratory thrombophlebitis as a presenting sign of visceral malignancy,” a condition that is still referred to as Trousseau's syndrome.1 Although it is usually attributed to venous or less frequently arterial thromboemboli that occur in a cancer-related hypercoagulable state, it may also be a sequela of embolization of occult tumor itself.2,3 The hypercoagulability of malignancy is the second most common cause of acquired thrombophilia with antiphospholipid syndrome as the leading cause.4 Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) is another mechanism of arterial thromboembolism encountered in patients with neoplastic disease. It is characterized by sterile vegetations composed of platelets and fibrin that adhere to valvular structures, most commonly found along coaptation lines, and susceptible to embolization.2,5 Adenocarcinomas of the lung and ovary comprise nearly 50% of the cases, followed by hematologic malignancies that account for 25%.5–8 Therefore, when evaluating patients with NBTE without a clear etiology, an occult neoplasm must be excluded.

Here we report the case of a patient with NBTE secondary to clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary with clinical manifestations of venous thrombosis and pulmonary and arterial emboli. Clear cell ovarian adenocarcinoma is recognized as a distinct histologic entity that differs from other types of adenocarcinoma.9 Originally described as “hypernephroma of the ovary,” these tumors are more akin to renal cell carcinomas and not commonly associated with NBTE.9

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old previously healthy woman presented with new-onset, sharp, intermittent, and diffuse abdominal pain that had begun 1 day earlier. The pain did not radiate and was only exacerbated by movement. She also complained of associated nausea and several bouts of emesis and loose stools. On presentation, she was febrile, tachycardic, with a regular rate and rhythm, and a grade 2/6 holosystolic murmur heard best at the apex with radiation to the axilla. Her lungs were clear on auscultation, and her abdomen was distended and tender with hypoactive bowel sounds. A pelvic examination demonstrated a “frozen pelvis” consistent with endometriosis. Laboratory tests were unremarkable with the exception of an elevated white blood count of 21, 700% and 14% bands. Abdominal computer tomography (CT) scan revealed a large, multi-lobulated, cystic mass in the right pelvis (Fig. 1). She was admitted to the hospital with differential diagnoses of pelvic abscess, endometriosis, or ovarian cancer. She underwent a CT-guided percutaneous pelvic mass biopsy, which revealed necrotic tissue and benign fibrotic debris. Meanwhile, elevated plasma levels of CA-125 at 1,315 U/mL (normal: 0 to 30) and carcinoembryonic antigen at 4.1 mg/mL (normal: 0 to 2.5) were detected. As a result, a colonoscopy was performed that was unremarkable. The following day, she developed transient neurologic deficits consisting of a right-sided facial droop and visual disturbances. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was nondiagnostic and demonstrated 2 small foci of increased signal without ring enhancement in the subcortical white matter of the right frontal lobe. Carotid arterial Dopplers and an electroencephalogram were normal. A diagnostic laparoscopy performed to further evaluate the mass showed a ruptured ovarian endometriotic cyst with a “chocolate fluid” appearance, and an intact, large endometrioma in the right pelvic cul-de-sac, with normal omentum and peritoneal surfaces. She was diagnosed with endometriosis. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) performed to evaluate the neurologic symptoms demonstrated a 0.7 × 0.9 cm nodular, mobile echodensity on the atrial surface of the anterior mitral valve leaflet associated with severe mitral regurgitation without evidence of leaflet destruction; a 0.5 by 0.6 cm nodular echodensity attached to the Eustachian valve in the right atrium; and 0.8 by 1.0 cm and 0.7 by 0.9 cm nodular mobile echodensities attached to the chordal structures in the right ventricle (Fig. 2 and Video 1). The patient was suspected to have infective endocarditis and empiric therapy was initiated with intravenous antibiotics. Despite persistent high-grade fevers and leukocytosis, serial blood cultures remained sterile. Subsequently, she suffered pulmonary, coronary, splenic, and renal embolic events. In addition, she also developed an acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. Extensive thrombophilic evaluation including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), antiphospholipid antibodies (cardiolipin IgG and IgM), Factor-V Leiden mutation, homocysteine, Protein-S, Protein-C, and Antithrombin-III levels, was unremarkable. Ultimately, a diagnosis of NBTE was entertained. Because of persistent pelvic and abdominal pain, the patient underwent an abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingoopherectomy, once her clinical status stabilized. Pathologic specimens revealed stage IIC clear cell adenocarcinoma of the ovary as well as severe pelvic endometriosis. To date, she has not experienced recurrent thromboembolic events on antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, and chemotherapy. Follow-up echocardiograms have shown a gradual regression in the size and the extent of intracardiac masses and vegetations as well as the severity of mitral regurgitation (Fig. 3).

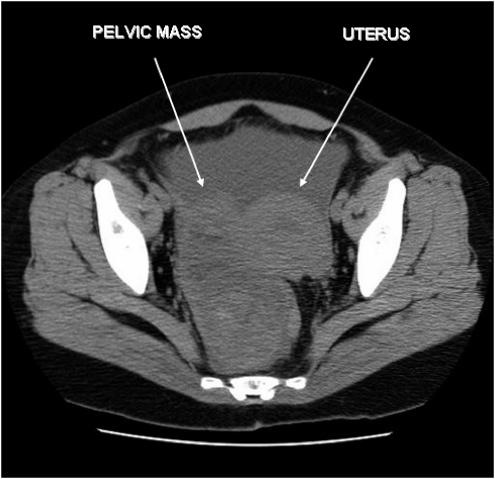

FIGURE 1.

Computer tomographic scan of the pelvis demonstrating a large, space-occupying, multilobulated, cystic appearing mass in the right pelvis displacing the uterus and rectum, measuring 12.5 × 6.5 × 5.5 cm in dimension.

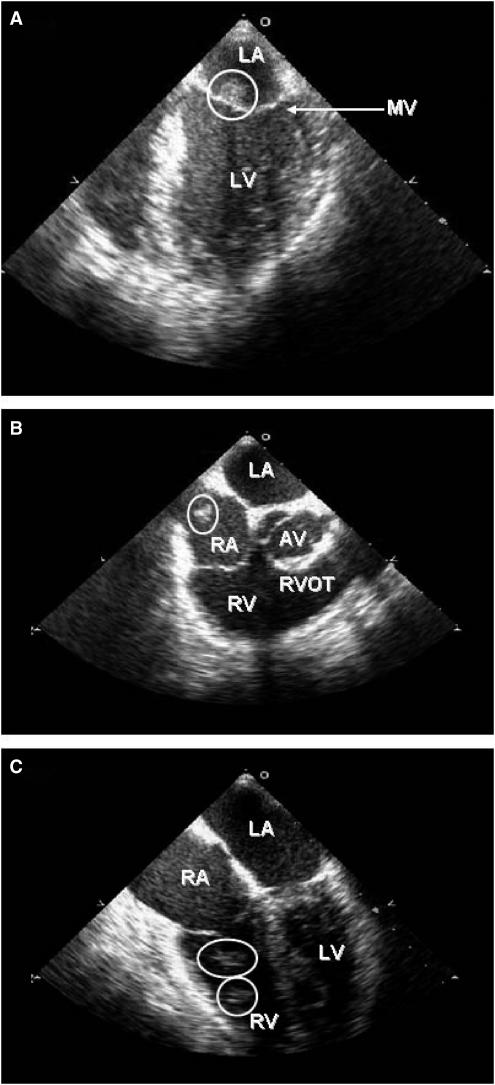

FIGURE 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram illustrating the intracardiac vegetations and masses identified by circles; (A) shows a large, nodular echodensity on the atrial aspect of the anterior mitral valve leaflet; (B) shows a smaller echodensity attached to Eustachian valve in the right atrium; and (C) shows 2 nodular echodensities attached to chordal structures inside the right ventricle. AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MV, mitral valve; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; and RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract. Video 1. Transesophageal echocardiogram showing a large, mobile, nodular echodensity on the atrial surface of the anterior mitral valve leaflet with absence of thrombus in the left atrial appendage.

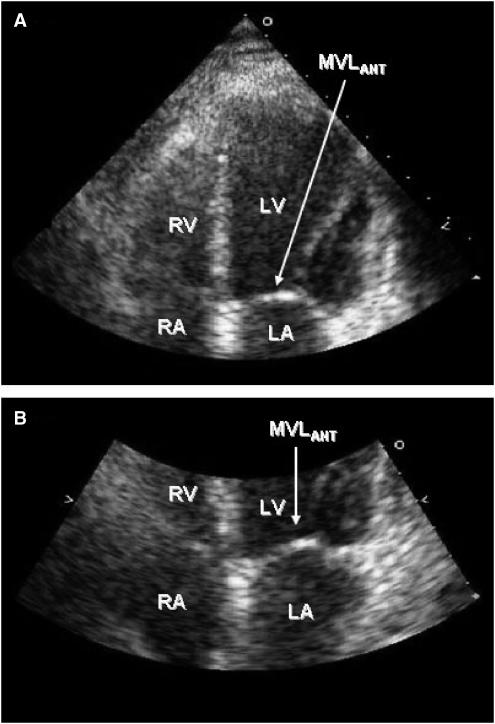

FIGURE 3.

Follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram; (A) no longer shows the nodular echodensity attached to the anterior mitral valve leaflet (MVLANT) (arrow) and (B) shows a close-up of the mitral valve and its anterior leaflet (arrow).

NONBACTERIAL THROMBOTIC ENDOCARDITIS

Endocarditis has been traditionally classified as infective or thrombotic. However, distinction between the 2 can sometimes become a diagnostic dilemma. Formerly known as marantic endocarditis, NBTE is a rare condition that normally occurs in the setting of advanced malignancy and hypercoagulable states.5 Originally described by Ziegler in 1888, the term NBTE was first introduced by Gross and Friedberg in 1936.10 However, it was not until 1954 when Angrist and Marquiss first called attention to the frequent association of systemic emboli with this condition.10 A diagnosis of NBTE is most commonly made at autopsy with an incidence of approximately 0.9% in the adult population.11 The sterile vegetations consist of degenerating platelets interwoven with strands of fibrin deposited on cardiac valves, and are often very friable.12 The pathogenesis of NBTE is not fully understood. However, it has been hypothesized that an interaction between monocytes or macrophages and malignant cells may result in release of tumor necrosis factor and interleukins triggering endothelial damage and sloughing there by leading to a thrombogenic surface.2 This interaction may also activate platelets and clotting factors which could further result in thrombosis.2

Although NBTE has been reported in every age group, it most commonly affects those between the fourth and eighth decades of life.12 Many of these patients share common risk factors for infective endocarditis, and the diagnosis can be often confused with that of culture-negative infective endocarditis. Indeed, NBTE may be associated with malignancy, connective tissue disorders, valvular pathology, and acute or chronic inflammatory processes (Table).13 The vegetations are frequently located on left-sided heart valves, with 64% involving the mitral, 24% involving the aortic, and in 9% involving both.11 Cases of NBTE involving right-sided heart valves, although rare, have been described.12,14 Vegetations on the atrioventricular valves are commonly present on the atrial surface, while those involving the semilunar valves are usually found on the ventricular surface of the valve.12 The reported incidence of clinical embolic events in NBTE varies between 14% and 91%.10,15 Autopsy series demonstrate systemic emboli in nearly half of the patients, most commonly affecting the cerebral vascular bed.10,11,15–17 Other common sites of emboli include the coronary, splenic, renal, and mesenteric circulation.11,15,16 The initial clinical manifestation of NBTE is seldom from cardiac valvular dysfunction, but in as many as 30% of cases it is due to arterial or venous emboli with neurologic symptoms being most common.5,15

There is a strong association between NBTE and neoplastic disease. An echocardiographic study of 200 living patients with various cancers found evidence of NBTE in approximately 19%, which was 10 times more prevalent than in the control group.18 In a study of 171 cases of NBTE encountered at autopsy over a period of 22 years, malignancy was detected in 59% of cases.11 Malignancies most frequently associated with NBTE were adenocarcinomas of the lung, ovary, biliary system, pancreas, and stomach. The neoplasms were frequently mucin-secreting adenocarcinomas. Thus, in evaluating patients with NBTE without a clear etiology, an underlying malignancy must always be excluded.

DIAGNOSIS

During the preechocardiography era, a diagnosis of NBTE was difficult and commonly made postmortem. Even now, this diagnosis is usually not suspected until the occurrence of embolic events and vascular complications, as in our patient. Moreover, as in this case, the diagnosis can be often confused with that of culture-negative infective endocarditis. Transesophageal echocardiography has proven to be an invaluable tool in the diagnosis of NBTE. Valvular vegetations along coaptation lines without destruction of valvular tissue are suggestive of NBTE.15 Presence of both left-and right-sided vegetations, as seen in this patient, is more consistent with NBTE as opposed to infective endocarditis, which normally affects heart valves in a unilateral fashion. Spontaneous venous thromboembolism is also more likely in the setting of NBTE. Additional clinical clues include negative blood cultures, absence of clinical signs of infection, and a normal thrombophilic screen. Recent studies have also emphasized the role of modern neuroimaging techniques and have demonstrated that those with NBTE more frequently develop multiple, widely distributed, small and large strokes in several cerebral territories on diffusion-weighted MRI, whereas single or focal lesions and territorial infarctions are more characteristic of infective endocarditis.5,19

TREATMENT

Anticoagulation remains the mainstay of therapy for NBTE, with recent literature supporting the use of intravenous unfractionated heparin.5,10,12,20 Caution is necessary as anticoagulation can be detrimental in patients with extensive cerebral infarction. The case for anticoagulant therapy is further strengthened by the notion that Trousseau's syndrome and NBTE have a common substrate of disseminated intravascular coagulation.10,12 The use of an oral vitamin K antagonist does not appear to be as efficacious.10 The utility of outpatient therapy with low molecular weight heparins, although not yet established, has been advocated and may greatly improve patient quality of life.10

The indications and appropriate timing of surgical therapy in NBTE have not been formally evaluated. However, surgery may be considered in those with potentially curable cancers. Presence of severe valvular dysfunction, recurrence of embolic events despite adequate anticoagulation, and uncertainty regarding diagnosis and etiology are considered indications for surgery.15 Surgical preservation of the affected valve may be possible in selected patients with NBTE in contrast to those with infective endocarditis, in whom surgical intervention more often mandates removal of the native valve and replacement with a prosthesis.15

SUMMARY

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis is often not readily diagnosed and should be considered in patients with valvular vegetations, significant valvular dysfunction, multiple embolic events, or venous thrombosis. It commonly occurs in the setting of malignancy-associated hypercoagulable state. Once a diagnosis of NBTE has been made and primary thrombophilia is excluded, the patient should undergo exhaustive evaluation for malignancy particularly adenocarcinomas. A distinction of NBTE from infective endocarditis is of paramount importance in terms of the therapeutic strategy. Valvular vegetations along coaptation lines without leaflet destruction, presence of both left- and right-sided vegetations, simultaneous occurrence of venous thromboembolism, negative blood cultures, and absence of clinical signs of infection are all suggestive of NBTE. Transesophageal echocardiography is the preferred diagnostic tool in establishing the diagnosis. While the therapy includes anticoagulation and control of the underlying malignancy, the optimal mode of anticoagulation remains yet to be established.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khorana AA. Malignancy, thrombosis and Trousseau the case for an eponym. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:2463–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2003.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bick RL. Cancer-associated thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:109–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasi SH, Juan CJ, Dai MS, Kao WY. Trousseau's syndrome related to adenocarcinoma of the colon and cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:493–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas RH. Hypercoagulability syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2433–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowski A, Ghodsizad A, Cohnen M, Gams E. Recurrent embolism in the course of marantic endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:2145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedikian A, Valdivieso M, Luna M, Bodey GP. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patientscomparison of characteristics of patients with and without concomitant disseminated intravascular coagulation. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1978;4:149–57. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Nogawa S, Umezawa A, Hata J, Fukuuchi Y. Expression of interleukin-6 in cerebral neurons and ovarian cancer tissue in Trousseau syndrome. Clin Neuropathol. 2002;21:232–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukai M, Hamada M, Hiwada K, Kokubu T, Nakajo A, Go S. Cerebral and myocardial infarction induced by nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in a patient with ovarian cancer report of a case. Jpn J Med. 1988;27:321–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.27.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy AW, Biscotti CV, Hart WR, Webster KD. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;32:342–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem DN, Stein PD, Al-Ahmad A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in valvular heart disease—native and prosthetic the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:457–482. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.457S. S S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner I. Nebakterialni tromboticka endokarditida—studie 171 pripadu [Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis—a study of 171 case reports] Cesk Patol. 1993;29:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez JA, Ross RS, Fishbein MC, Siegel RJ. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis a review. Am Heart J. 1987;113:773–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eiken PW, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, McBane RD, Zehr KJ. Surgical pathology of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in 30 patients, 1985–2000. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1204–12. doi: 10.4065/76.12.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagura H, Yamanouchi H. Cerebral infarctions in elderly patients with anemia. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1992;29:918–21. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.29.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabinstein AA, Giovanelli C, Romano JG, Koch S, Forteza AM, Ricci M. Surgical treatment of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis presenting with stroke. J Neurol. 2005;252:352–5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojeda VJ, Frost F, Mastaglia FL. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis associated with malignant disease a clinicopathological study of 16 cases. Med J Aust. 1985;142:629–31. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb113555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graus F, Rogers LR, Posner JB. Cerebrovascular complications in patients with cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:16–35. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edoute Y, Haim N, Rinkevich D, Brenner B, Reisner SA. Cardiac valvular vegetations in cancer patients a prospective echocardiographic study of 200 patients. Am J Med. 1997;102:252–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA, Buonanno FS. Acute ischemic stroke patterns in infective and nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis a diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2002;33:1267–73. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000015029.91577.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrera de Pablo P, Esteban-Esteban E, Gimenez-Soler JV, Pareja-Martinez A, Moscoso del Prado J. Endocarditis trombotica no bacteriana como manifestacion inicial de neoplasia pulmonar [Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis as initial event of lung cancer] An Med Interna. 2004;21:495–7. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992004001000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.