Abstract

The plasma membranes of epithelial cells plasma membranes contain distinct apical and basolateral domains that are critical for their polarized functions. However, both domains are continuously internalized, with proteins and lipids from each intermixing in supranuclear recycling endosomes (REs). To maintain polarity, REs must faithfully recycle membrane proteins back to the correct plasma membrane domains. We examined sorting within REs and found that apical and basolateral proteins were laterally segregated into subdomains of individual REs. Subdomains were absent in unpolarized cells and developed along with polarization. Subdomains were formed by an active sorting process within REs, which precedes the formation of AP-1B–dependent basolateral transport vesicles. Both the formation of subdomains and the fidelity of basolateral trafficking were dependent on PI3 kinase activity. This suggests that subdomain and transport vesicle formation occur as separate sorting steps and that both processes may contribute to sorting fidelity.

INTRODUCTION

Plasma membranes are not static structures. Rather, they are dynamic organelles that continually internalize membrane and proteins in a process termed endocytosis. Indeed, the entire surface of a typical cell may pass through the endocytic system every 2 h (Besterman and Low, 1983). The endosomal system is designed to segregate cargo destined for lysosomal degradation from that destined for recycling to the plasma membrane. Several types of endosomes ensure that the sorting of cargo is performed correctly. Endocytic cargo first enters the early endosome (EE), where many receptor-bound ligands dissociate from their receptors, and are sorted via late endosomes (LE) toward lysosomes (Brown et al., 2000b). Nonrecycled receptors, such as the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, also follow this LE to the lysosome pathway (Kornfeld and Mellman, 1989). In contrast, other proteins, and particularly receptors, including the transferrin (Tfn) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors (LDLR), return to the plasma membrane from the endosomes and participate in multiple rounds of endocytosis. This can occur via one of two routes: direct return to the surface from EEs (occurs for 65% of recycled receptors) or return to the cell surface via recycling endosomes (REs; occurs for 35% of recycled receptors; Ghosh and Maxfield, 1995; Knight et al., 1995; Sheff et al., 1999). Tfn is a particularly useful ligand experimentally, because it remains bound to its receptor (TfnR) through the endocytic recycling process and is released only after returning to the cell surface (Hopkins and Trowbridge, 1983; Odorizzi and Trowbridge, 1997). Labeled Tfn is therefore commonly used as a tracer to follow the recycling pathway.

Polarized epithelia present a further sorting challenge because they have separate apical and basolateral plasma membrane domains with different protein and lipid compositions (Drubin and Nelson, 1996; Nelson, 2003). After their synthesis, nascent proteins are delivered to the correct surface based on basolateral sorting determinants in their cytoplasmic tails or apical sorting determinants in their luminal domains (Matter and Mellman, 1994; Mellman, 1996). Sorting signals are highly conserved among different cell types and species. For example, most proteins that are on the basolateral surface in canine kidney tubule cells localize to the dendrite membrane (the basolateral equivalent of neuronal cells) when expressed in rat neuronal cells (Winckler and Mellman, 1999).

The maintenance of cell polarity also requires the endocytic system to perform the crucial function of delivering receptors to the appropriate plasma membrane domain rather than randomly to the surface. This sorting occurs at multiple levels. In epithelial cells, separate EE compartments lie below the apical and basolateral surfaces (Bomsel et al., 1990), such that apically endocytosed cargo does not have access to the basolateral EE and vice versa (Sheff et al., 2002). The recycling endosome (RE), located superior to the nucleus, receives traffic from both the apical and basolateral EEs (Sheff et al., 2002). It returns plasma membrane receptors to the correct surface by sorting apical from basolateral cargo, before their inclusion into separate transport vesicles. In Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, the RE is the major site of polarized sorting along the endocytic system (Gruenberg et al., 1989; Brown et al., 2000a; Wang et al., 2000; Sheff et al., 2002).

Recent evidence has suggested that the RE may play an additional important role as a warehouse for both membrane and surface proteins. Although only a minority of each internalized membrane protein population passes through this organelle during each cycle, the rate of passage (or flux) through the RE is slower than through the EE, resulting in an accumulation of both membrane and proteins in the RE (Hopkins et al., 1994; Guo et al., 1996; Mellman, 2000). For example, up to 70% of TfnR is found in the RE at steady state. New membrane is recruited from the RE for delivery to the forward edge of the cell during cell movement (Hopkins et al., 1994). Similarly, receptors such as the AMPA receptor accumulate within the RE of neurons and are recruited from it during long-term potentiation (Park et al., 2004). It has recently also been suggested that a substantial fraction of some nascent proteins may be delivered from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to REs for initial sorting before delivery to the plasma membrane (Futter et al., 1995; Ang et al., 2004). In any case, the fact that an individual receptor may pass through the endocytic system 50–100 times makes the RE the major site of polarized sorting in the cell. Given that even a small disturbance in protein targeting can lead to a loss of cell polarity sufficient to cause lethal disease (Koivisto et al., 2001), it will be important to learn more about how sorting is accomplished in this organelle.

Basolateral sorting in the Golgi and endosomes is controlled by sorting determinants in the cytoplasmic tails of cargo proteins (Breitfeld et al., 1989; Matter et al., 1993; Futter et al., 1998). Some basolateral sorting determinants are dependent on the clathrin adaptor subunit μ1-B. These include the tyrosine-based YXXΦ found in the LDLR, and the Gly-Asp-Asn-Ser determinant present in the TfnR (Odorizzi and Trowbridge, 1997; Folsch, 2005). Non-μ1-B–dependent dileucine determinants exist as well, such as that found in the Fc receptor (Matter et al., 1992; Mellman et al., 1993). Thus, there are multiple pathways to the basolateral surface (Ohno et al., 1996; Folsch et al., 1999). Kinetic analysis of endocytosis has shown that basolateral sorting in the RE is over 93% efficient (Sheff et al., 1999). Such efficiency is unusual in single-step biological systems, suggesting that RE sorting may be a multistep process, but the details of how it is accomplished are controversial. One possible mechanism could be the segregation of different cargoes into distinct subdomains of the RE membrane, which would allow the selective inclusion of apical and basolateral cargo into specific types of transport vesicles from presorted subdomains. This idea is not without precedent, as both EEs and LEs are known to contain distinct subdomains defined by the presence of different Rab proteins (Sonnichsen et al., 2000). Moreover, it has been proposed that these subdomains serve as part of the EE sorting process (Sonnichsen et al., 2000; De Renzis et al., 2002; Fouraux et al., 2004). Alternatively, apical sorting may require passage through both the RE and an apical recycling compartment, the latter possibly also serving as a regulatory step (Leung et al., 2000).

Because of the primacy of the RE for polarized sorting, we have studied the sorting of apical and basolateral proteins in REs, using high-resolution imaging and three-dimensional (3D)-reconstruction. Because it has been argued that nonpolarized cells possess cognate sorting pathways, we also compared RE sorting in polarized cells to that of the cognate perinuclear recycling endosomes of nonpolarized cells (Yoshimori et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2000a). Our observations reveal an entirely new level of sorting that occurs within the RE, before budding of transport vesicles, not observed in previous studies (Mukherjee and Maxfield, 2000; Wang et al., 2000). In polarized cells, REs presort apical and basolateral proteins into separate membrane subdomains within an individual endosome, but this does not occur in nonpolarized cells. Our studies further suggest that these subdomains rely on lipid cues for their organization. We therefore propose that sorting relies on both 1) lateral segregation into subdomains within the RE and 2) separate selective budding of cargo into transport vesicles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All labeled Tfns were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Anti-Fc ectodomain antibody was derived from clone 2.4G2 produced in the Mellman Laboratory (Yale University) and directly labeled with Alexa-488– or Alexa-546–labeling kits from Molecular Probes. Anti-NgCAM was clone 8D9 (from NIH hybridoma bank) produced in the Mellman and Sheff laboratories and detected with an anti-mouse secondary (from Molecular Probes). Wortmannin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). AlF4− was produced from reagent grade NaF and AlCl4 to create a 50 μM Al, 30 mM F solution. Transwell filter inserts were obtained from Corning (Corning, NY). All other chemicals were reagent grade.

Plasmids and Constructs

Fc ectodomain fused to LDLR cytoplasmic domain [FcLR(5-22)] in pCB6 was derived in the Mellman laboratory, subcloned into the pShuttle vector and then recombined into the pAdEasy viral backbone in bacteria according to manufacturer's directions. Full-length NgCAM was cloned into pShuttle and recombined into pAdEasy in the same manner. LDLR was provided in the pCB6 expression vector, a kind gift from the Mellman laboratory. MDCK cells stably transfected with human transferrin receptor (MDCKT) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human Tfn receptor (CHOT) cells were derived previously in the Mellman laboratory, and both express human Tfn receptor from a cytomegalovirus promoter in the pCB6 vector. Selection was performed using G-418 at 0.5 mg/ml, and expression was induced before use by 10 mM butyrate treatment for 18–22 h followed by 2–4-h recovery in normal media.

Cell Culture

MDCKT cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) +8% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA) supplemented with G-418 and glutamine. CHOT cells were grown in α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), G-418 (0.5 mg/ml), and glutamine. MDCKT cells were split 1:1.2 onto Transwell filters in the same media. For adenoviral infections, virus was added at an MOI of ∼5 on day 1 after seeding in serum-free medium on the apical side only. After 2 h, an equal volume of regular medium was added, and cells were allowed to grow. On day 3, (or on the day before imaging for the time courses) cells were induced overnight with 10 mM butyrate in fresh medium. Cells were typically allowed to recover for 4 h in fresh medium. For cells labeled on day 1 after plating, infection and induction were performed as for a complete 4-d polarization, after which the cells were trypsinized and plated without further induction. They were labeled on the next day, after starvation in 37°C DMEM for 30 min and subsequent chilling on ice. A minimal volume of medium was used for apical labeling (was with minimal volumes of media to cover the Transwell), with 2.4G2 antibody added at 1:200 for prelabeling. Transwells were placed on minimal sized droplets of medium containing Tfn (5 mg/ml) of a different color that of the 2.4G2, diluted 1:75 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with Ca2+ and Mg2+. Similar conditions were used for CHOT cells grown on coverslips. Neurons were cultured as described previously (Wisco et al., 2003) and after 9 d of in vitro culture were infected with Adeno FcLR(5-22) or Adeno-NgCAM for 24 h. Neurons were Tfn starved, in N2.1 medium lacking Tfn, for 1 h and then allowed to take up cy-3 Tfn (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C. Prelabeled 2.4G2 or 8D9 and Tfn were then further bound at 12°C for 30 min. To ensure saturation of the recycling pathway, cells were washed and then chased in the presence of cy3-Tfn for 60–110 min and then chased in the absence of Tfn for 25 min to specifically label REs before fixation. For transcytosis assays in neurons, hippocampal cells were preloaded with FITC-Tfn at 37°C and then labeled for 30 min at 16°C with a mix of labeled Tfn and anti-NgCAM ectodomain antibody. Unbound anti- NgCAM antibody was washed away and bound antibody chased for 60 min at 37°C. Twenty-five minutes before fixation, Tfn was washed away in order to chase it to the REs. Uninduced MDCK cells were infected with adenovirus constructs expressing FcLR(5-22) and human TfnR and were not treated with butyrate. MDCKT cells labeled with wheat germ agglutinin and anti-LDLR were transfected with the LDLR in pCB6 using fugene-6 on day 1 and labeled on day 4 without butyrate induction.

Light Microscopy

Cells were labeled apically with anti-FcLR(5-22), and basolaterally with Tfn. FcLR(5-22) is an apical chimeric receptor that includes the Fc receptor ectodomain and the endocytic determinant of the LDLR tail. The construct is directed entirely apically (Matter et al., 1993). Endocytosis of FcLR(5-22) was followed using an Alexa-568–labeled antibody directed against the extracellular domain. This antibody (2.4G2) does not dissociate at endosomal pH and remains bound to the receptor for multiple rounds of internalization (Ukkonen et al., 1986). Incubation at low pH at 4°C before fixation was used in all cases (except as noted) to remove surface-bound antibodies. Live cells were imaged immediately after the low-pH wash (no fixation) with the microscope at 20°C. High-specificity labeling with Tfn was achieved using MDCKT cells. Recombinant adenovirus (Adeno-FcLR) was used to achieve high levels of FcLR(5-22) expression. Even using a highly efficient overexpression system, TfnR is still found to be basolaterally enriched, whereas FcLR(5-22) is apically enriched, as demonstrated previously (Sheff et al., 2002). Alexa-488 wheat germ agglutinin was also used to label apical proteins with selective addition to the apical plasma membrane. Fixed cells were permeabilized with saponin and immunolabeled for the LDLR as an alternative basolateral protein. Fixed cells were imaged using a Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) LSM 510 Confocal Microscope fitted with an inverted Zeiss 100M base and a 63× oil immersion lens. For 3D imaging, a minimum of 30 optical sections were taken through the height of the cell. Digital microscopy files were transferred to an Apple (Cupertino, CA) G5 Macintosh computer, for analysis using Velocity software (Improvision, Lexington MA). This software was used for both image visualization and quantification.

RESULTS

REs in MDCKT Cells Segregate Apical and Basolateral Cargoes

It has been established that apical and basolateral recycling pathways intersect in the RE (Knight et al., 1995; Hoekstra et al., 2004). However, whether apical and basolateral proteins mix homogenously in the RE is controversial (Bonifacino and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2003). Therefore, we imaged apical and basolateral cargoes applied to MDCKT and chased into the RE. Prior experiments had demonstrated that it takes 2.5 min for a pulse if Tfn to reach the EE (colocalization with Rab5) and 25 min to accumulate selectively in the RE (as determined by segregation from fluorescently labeled EEs and kinetic analysis; see Figure 1). The REs were therefore selectively labeled by a 25-min chase. Although Rab11a is a reliable RE marker in nonpolarized cells, it labels only subsets of REs in polarized cells (Ullrich et al., 1996; Prekeris et al., 2000) and thus could not be used as a RE marker in our study. REs were instead selectively labeled using pulses of two differently colored Tfns, one of which labels EEs and the other REs. Specifically, Alexa 488-Tfn was applied to the basolateral side of MDCKT cells on ice, with a 25-min chase at 37°C. For the last 2.5 min of chase, we applied Alexa-568-Tfn from the basolateral side. There was virtually no overlap between red (EE) and green (RE) labeled endosomes (Figure 1A). We therefore functionally defined REs as those endosomes that label with basolaterally bound Tfn after a 25-min chase.

Figure 1.

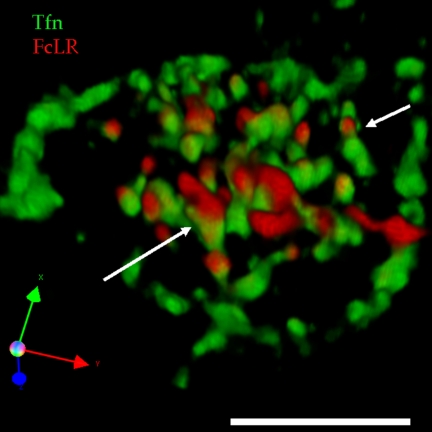

Recycling Endosomes of polarized cells have subdomains. (A) Early endosomes (EE) and RE in MDCKT cells labeled with timed pulses/chases of basolaterally applied Tfn. Tfn (green) was internalized for 22.5 min to label REs, the cells were chilled, Alexa 546-Tfn (red) was bound to the basolateral surface, cells were rewarmed to 37°C for an additional 2.5 min to label EEs. (B) MDCKT cells infected with adeno FcLR(5-22) and induced with butyrate, then labeled with apical anti-FcLR(5-22) (red), and basolateral Tfn (green), and fixed with PFA. Cargoes segregate into RE subdomains. Serial confocal sections were reconstructed into this 3D projection. Inset is enlarged RE. (C) MDCK cells infected with adeno TfnR and adeno FcLR(5-22), labeled as in B but not induced with butyrate. (D) MDCKT cells infected induced and labeled as in B but imaged live (without fixation). Triple arrows indicate rotation of axes. Bars are 10 μm.

To study polarized traffic through the RE, we used TfnR as the basolateral cargo and FcLR(5-22) as the apical cargo (see Materials and Methods). Prior kinetic analysis and morphological observation had demonstrated that, although anti-FcLR(5-22) labels the entire apical pathway, most of the label is in REs after 25 min (Sheff et al., 2002). Similarly, virtually all Tfn, not yet recycled out of the cell, is in the RE at 25 min (Sheff et al., 1999, 2002). Imaging with confocal microscopy was used to generate an image stack of 35 × 0.3-μm-thick optical slices. Previously generated 2D images of supranuclear endosomes in these and similar cells had shown clear areas of overlap between apical and basolateral ligands, as well as areas that are depleted of Tfn, which have been interpreted to be either apical REs distinct from the common RE or as apical EEs (Leung et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). We likewise observed regions greatly enriched for basolateral proteins (green), other regions greatly enriched for apical proteins (red), and areas of overlap (yellow; Figure 1B). Because MDCKT cells do not have a single central microtubule-organizing center, the number and distribution of REs is variable from cell to cell. Nevertheless, they are all supranuclear and are labeled with Tfn under the conditions used in our study.

The apical marker used in our studies is an anti-FcLR antibody that does not dissociate from the receptor and so is continuously recycled via the plasma membrane. However, because passage through the apical EEs is faster than that through the REs, most internalized ligand is in the RE after 25 min of chase (Sheff et al., 2002). Some endosomes labeled with FcLR(5-22) but not Tfn were observed near the periphery. These were classified as EEs rather then REs because they colabeled with internalized dextran, a fluid phase marker not sorted to REs in control experiments (unpublished data).

To assess whether the distinct domains we observed were continuous or discrete in 3D space, the image stack was processed into a 3D image using Volocity software (San Francisco, CA). Examination of labeled endosomes rotated in 3D space (see Figure 1B and Supplementary Movie 1) revealed REs to be composed of three identifiable subdomains, apical (red), basolateral (green), and mixed (yellow), that appeared to be continuous. The RE shown in the inset was typical of those found in nearly every cell examined. These images suggested that apical and basolateral cargo are laterally segregated from each other in the RE membrane.

The morphology that we observed was in cells treated with sodium butyrate, to promote TfnR expression, and fixed with PFA. Either of these manipulations may affect the morphology of the RE. Furthermore, butyrate treatment raised the transepithelial resistance (TER, measuring formation of a tight polarized monolayer) on day 4 from 115 ± 4.5 to 372 ± 74.6 Ohms·cm2. After 24-h recovery, the butyrate-treated cells still had a higher TER of 155 ± 5.0 Ohms·cm2 compared with controls with a TER of 84 ± 8.8 Ohms·cm2. We therefore prepared MDCK cells infected with both adeno-FcLR(5-22) and adeno-human TfnR, which did not require induction (Figure 1C). Cells were labeled as before. The same pattern was observed, suggesting that it is not an artifact of butyrate induction. To examine the possibility of fixation artifacts, induced MDCKT cells, labeled as before were imaged live at 20°C (Figure 1D). Only single image stacks from each transwell were acquired immediately after labeling to eliminate formation of domains while on the microscope. The same pattern was observed as in fixed cells, suggesting that subdomain formation was not an artifact of fixation. Taken together these results suggest that the observed RE subdomains reflect a physiological state rather than an artifact of processing.

It was possible that this segregation was unique to the pair of cargo proteins we had selected. To control for this possibility, MDCK cells expressing the human LDLR (a recycling basolateral protein) were apically labeled with wheat germ agglutinin (a lectin binding a large number of apical proteins), which was internalized for 25 min. No butyrate induction was used with LDLR expression. The apical surface was washed with N-acetyl glucosamine to remove excess wheat germ agglutinin, and the cells were permeabilized and stained for LDLR, which appeared in both endosomes and on the basolateral surface. Although signal levels were very high and a large number of proteins were thus labeled, separate apical and basolateral subdomains could be observed in these cells (Supplementary Movie 2). Together these results suggest that we are observing true apical and basolateral subdomains in REs.

REs in Nonpolarized Cells Do Not Segregate Apical and Basolateral Cargoes

Nonpolarized cells are thought to possess sorting pathway cognates to the apical and basolateral pathways that are characteristic of polarized cells (Yoshimori et al., 1996). Therefore, we examined whether cargo segregation occurs in nonpolarized cells. We infected CHOT cells with Adeno-FcLR(5-22). Coverslip-grown cells were labeled (on ice) with both ligands in the same medium and chased into the cells for 25 min as above. Cells were examined by confocal microscopy and reconstructed in 3D (Figure 2A). The result was dramatically different from that for MDCKT cells: all Tfn label overlapped completely with anti-FcLR(5-22). Colocalization was also observed in HeLa cells (Figure 2A, inset), in spite of the fact that the RE appeared more fragmented and smaller than in CHOT cells. This result demonstrated that the colocalization in CHOT cells is a phenomenon common to at least some nonpolarized cell lines. It was also not an artifact of either butyrate induction of the TfnR in CHOT (but not HeLa) cells or of a loss of resolution due to the clumping of multiple organelles at the center of the CHOT (but not HeLa) cells. Peripheral structures containing anti-FcLR(5-22) but not Tfn correspond to EEs, as the anti-FcLR(5-22) antibody stays bound to its receptor and reinternalizes. Thus, although the REs of polarized epithelial cells were capable of segregating apical and basolateral cargo, the REs of nonpolarized cells were not.

Figure 2.

RE subdomains are a feature of polarized cells. (A) In nonpolarized CHOT and HeLa (inset) cell lines, apical and basolateral cargoes labeled as with Tfn (green) and anti-FcLR(5-22) (red) do not segregate into RE subdomains. Red areas represent EEs, which remain labeled by the antibody to FcLR(5-22). Arrow indicates area of overlap. (B) In a rat hippocampal neuron, apical and basolateral cargoes (labeled as in A) segregate into RE subdomains. Pulse period was 108 min at 37°C, chase was 25 min. Inset, enlarged RE. Triple arrows indicate rotation of axes. Bars are 10 μm.

REs in Neuronal Cells Segregate Apical and Basolateral Cargoes

To rule out that the RE subdomains we had observed are unique to MDCKT cells, we also examined sorting in primary cultures of polarized rat hippocampal neurons. To this end, adeno-FcLR(5-22) was applied to the culture medium. The endogenous TfnR in these cells was sufficient to allow for visualization by adding labeled Tfn. Specifically, neurons were preloaded with FITC-Tfn at 37°C for 30 min, after which both FITC-Tfn and anti-FcLR antibody were bound for 30 min at 16°C. Unbound anti-FcLR antibody was then washed off, and bound anti-FcLR antibody was chased in the continued presence of FITC-Tfn at 37°C for 108 min, allowing for saturation of the endosomal system. Twenty-five minutes before fixation, FITC-Tfn was washed out in order to chase Tfn out of EEs and into the REs. The time course for the recycling of Tfn is similar for neurons and other cell types, with most Tfn being recycled out of the cell within 60 min (our unpublished data and Prekeris et al., 1999). This relatively complicated protocol was necessitated by the sensitivity of hippocampal neurons to the low temperatures usually used for binding studies and by the low abundance of TfnR in these cells compared with that in MDCKT cells.

Separate labeling of somatodendritic and axonal domains was not possible in this culture system, but fortuitously this means that the segregation of ligands depended entirely on the cellular sorting apparatus. REs in the soma of the neurons exhibited distinct subdomains enriched for either Tfn or FcLR, as had been observed in MDCKT cells (Figure 2B, inset). Importantly, these cells did not require induction with butyrate (used in MDCKT cells), thus ruling out butyrate treatment as a cause of subdomain formation. Taken together, these results suggest that the segregation of apical and basolateral proteins in REs is a specific function of polarized cells.

Subdomains Are Created by Sorting within the RE

The observed subdomains were static images and thus could have been due to either the docking of carriers entering the RE or sorting from a mixed population during exit from the RE. To resolve this issue, we took advantage of the 7% of the Tfn receptor that is present on the apical surface of MDCKT cells (Sheff et al., 2002), whose apical endocytosis can be visualized at sufficient Tfn concentration. We applied differently colored Tfns to the apical and basolateral surfaces of MDCKT cells, and anti-FcLR(5-22) in a third color to the apical surface. All were bound first at 4°C and then internalized at 37°C in the continuous presence of label for 25 min before being chased in the absence of label for another 25 min. This extra labeling at 37°C ensured brighter labeling of the endosomes with Tfn, whereas the 25-min chase enhanced specific labeling of the REs. The surface was acid washed to remove recycled anti-FcLR(5-22). FcLR(5-22) was segregated from the basolaterally applied Tfn as previously observed (Figure 3A). A few basolateral EEs (identifiable because they contain only basolateral Tfn) were also visualized by this protocol due to the high level of labeling of all endosomes (arrow in all panels). Importantly, apically and basolaterally applied Tfns colocalized almost perfectly (Figure 3B) in REs (arrowhead) but not in EEs (arrow). In contrast, apically applied Tfn segregated from apically applied anti-FcLR(5-22) (Figure 3C). The triple label (Figure 3D) demonstrated that apically and basolaterally applied Tfns colocalized, whereas both segregated from the apical FcLR(5-22). Thus, common destination rather than common entry point led to colocalization in the RE. These results strongly suggest that the observed subdomains were the consequence of cargo sorting after arrival at the RE rather than representing regions of entry into the RE.

Figure 3.

Cargo in RE subdomains segregates by destination rather than by membrane of origin. MDCKT cells expressing FcLR(5-22) were labeled apically with anti FcLR(5-22) (red) and Tfn (blue), and basolaterally with Tfn (green). Label was chased for 25 min at 37°C. High levels of all labels make EEs visible in this protocol. (A) Apical FcLR(5-22) versus basolaterally bound Tfn (green). (B) Apically bound (red) versus basolaterally bound (green) Tfns. (C) Apically bound FcLR(5-22) (red) versus apically bound Tfn (green). (D) Combined projection of all three dyes. Triple colocalization is white. Arrowhead indicates a colocalization of Tfns with segregation of FcLR(5-22). Triple arrows indicate rotation of axes. Bars, 10 μm.

The Transcytosing Receptor NgCAM Colocalizes with Apical Cargo in the RE.

It was possible that in the foregoing experiments, transferrin applied apically had reequilibrated with basolateral receptors within the REs. To further test if subdomains are dependent on the route of entry into the RE or of exit from the RE, we compared the distribution of two basolaterally applied ligands with different destinations. The distribution of basolaterally applied Tfn was compared with that of basolaterally applied anti-NgCAM antibodies. NgCAM, an axonal cell adhesion molecule, is an apical receptor when expressed in MDCKT cells. Surprisingly, it reaches the apical surface in MDCKT cells and also the axonal surface in hippocampal neurons, by transcytosis via the basolateral domain (Wisco et al., 2003; Anderson et al., 2005). The basolateral sorting determinant in the cytoplasmic tail is inactivated at the basolateral surface revealing a previously cryptic apical sorting determinant. NgCAM is endocytosed slowly from the basolateral surface, at one-tenth the rate of TfnR. This is consistent with constitutive internalization that does not involve recruitment to clathrin-coated pits. The apical sorting determinant traffics NgCAM to the apical domain, via the RE (Figure 4A). Basolaterally labeling NgCAM with antibodies and TfnR with Tfn allowed us to visualize these two cargoes as they enter the cell from the same (basolateral) surface, then separate in the RE, and ultimately reach opposite plasma membrane domains. Rat hippocampal neurons were infected with adeno-Ng-CAM. The live neurons were labeled with both the anti-NgCAM antibody and Tfn applied to the whole cell. We found that these labels were segregated in the REs, within the cell body (Figure 4B). In MDCKT cells, apical and basolateral plasma membrane domains can be accessed separately. Thus, we tested colocalization effects further by applying both anti-Ng-CAM and Tfn to the basolateral surface and anti-FcLR(5-22) to the apical surface. All were chased into the cell in the absence of label for 25 min. Residual external antibody was removed with an acid wash (Figure 4, C and D). Three representative cells are shown. In all cases the NgCAM labeling colocalized with that for the apical cargo anti-FcLR(5-22) and segregated from that for the basolateral cargo Tfn. This can be seen more clearly in Figure 4D, which shows pairwise comparisons of the three labels. Quantitative assessments used a 3D mask to identify objects in each channel. For each channel pair, overlapping fluorescence was calculated as a percentage of the total fluorescence for the channel being measured. Analysis of these and other (not shown) images (n = 3 images, 4 cells per image) demonstrated that 60% ± 10% of the Tfn was present in Tfn only subdomains, whereas 40% of Tfn overlapped with anti-FcLR(5-22). Anti-NgCAM overlapped anti-FcLR(5-22) almost completely. Together, these results suggest that apical cargo is segregated from basolateral cargo, even when both cargoes originate on the basolateral surface.

Figure 4.

Transcytotic NgCAM colocalizes with FcLR(5-22), but not with Tfn, in REs. (A) NgCAM trafficking through the MDCKT cell. Nascent NgCAM is delivered from the Golgi to the basolateral surface where it is phosphorylated (purple circle), which inactivates the basolateral sorting determinant. Basolateral NgCAM is then endocytosed and delivered, as an apically destined protein, to the REs. From there, it is delivered to the apical surface where it remains. Once bound to NgCAM at the basolateral surface, antibody 8D9 remains with the protein during basolateral to apical transcytosis. (B) In hippocampal neuron REs, axonally targeted NgCAM (red) segregates from somatodendritic Tfn (green). Inset shows subdomains, with NgCAM and TFN segregated into different subdomains of the same REs (arrows). (C) In MDCK cell REs, basolaterally labeled NgCAM (blue) colocalizes with apically labeled FcLR(5-22) (red) but not with basolaterally labeled Tfn (green). Three cells are shown. NgCAM and FcLR largely colocalize (purple), but segregate from basolaterally bound Tfn (green) at arrows. Yellow box indicates area enlarged in D. (D) REs from left cell in C, shown in label pairs. Each pair has been rendered in red/green for better contrast. Arrow indicates a single RE that illustrates the segregation of apically destined NgCAM and FcLR(5-22) from basolaterally destined Tfn. Triple arrows indicate rotation of axes. Bars, 10 μm.

Domain Segregation Does Not Result from Differences in the Sorting Kinetics for Apical and Basolateral Cargoes.

Our previous studies had established that exit from the REs is faster for basolateral (k = 0.07 s−1) than for apical (k = 0.019 s−1) cargo (Sheff et al., 2002). Thus, it seemed possible that the appearance of apical only subdomains could be a consequence of basolateral cargo being removed from some areas faster than apical cargo. If this were the case, we would expect to observe apical subdomains and “apical + basolateral” subdomains, particularly under our experimental conditions in which ligand is bound on ice and chased into the cell at 37°C for 25 min. However, the REs we visualized (Figure 1) contained both apical and basolateral subdomains. In fact, the infringement of basolateral cargo into the apical subdomains appeared greater than the reverse, suggesting that subdomain formation did not result from unequal rates of depletion of basolateral cargo from apical portions of the RE. Nevertheless, we further tested this possibility by testing the effects of AlF4−, a drug that selectively blocks basolateral exit from the REs (Sheff et al., 1999). Specifically, MDCKT cells were labeled with basolateral Tfn on ice and chased for 25 min at 37°C in the presence of AlF4−. In this experiment, Tfn was trapped in the RE and anti-FcLR(5-22) became equilibrated throughout the pathway, which would be expected to mask any separation based on kinetics of passage. We found that the treatment produced enlarged tubulated basolateral domains and virtually unchanged apical domains (Figure 5) and that this held true even after longer chase periods of up to 40 min (unpublished data). These findings indicate that lateral segregation into subdomains must be the result of a sorting process rather than of differential passage rates for apical and basolateral cargoes.

Figure 5.

Slowing basolateral traffic through the REs does not abolish subdomain formation. MDCKT cells were labeled on ice with apical anti-FcLR(5-22) (red) and basolateral Tfn (green). The cells were treated on ice for 30 min with AlF4−, and both labels were chased into the cells at 37°C in the presence of AlF4−. A 3D reconstruction of a typical cell is shown. Arrows indicate continued presence of apical and basolateral subdomains within the same RE. Bar, 10 μm. Triple arrow is axis of rotation.

RE Subdomains Form as Cells Polarize.

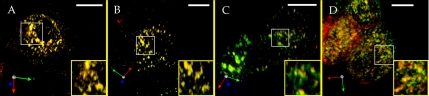

The RE subdomains found in the polarized, but not the nonpolarized, cell types tested here may either be features of polarized cells or develop as a consequence of the polarization process. To differentiate between these possibilities, we examined MDCKT cells at different stages of polarization after normal passaging. TER measurements of MDCKT cells grown on Transwells under these conditions (without butyrate induction) showed an abrupt increase from 49 to 104 ± 6.3 between days 3 and 4 after plating. MDCKT cells were plated onto Transwells at 83% of confluent density. Cells were treated with butyrate 20 h before labeling and removed from butyrate 4 h before labeling. Cells used for day 1 were treated with butyrate before passaging. The induced cells were trypsinized and grown for 24 h. They were labeled with basolateral Tfn and apical anti-FcLR(5-22) 1, 2, 3, and 4 d after plating. The monolayer is not complete before day 4 presenting a problem when labeling each side selectively. Fortunately, labeling in neurons had demonstrated that application of Tfn and FcLR(5-22) from all surfaces still resulted in labeling of subdomains. In this case, subdomains were not visible on days 1 and 2 (Figure 6, A and B), although the REs were readily labeled. The same result was obtained on day 1 if cells were first plated and then treated with butyrate on the same day as plating (unpublished results). On day 3, RE subdomain formation was variable (Figure 6C), with a subset of REs exhibiting their emergence (Figure 6C, inset). By day 4, subdomains were visible in REs of all cells examined (Figure 6D). This suggested that RE subdomains form along with polarization and that they are disrupted when cells are trypsinized and passaged.

Figure 6.

Formation of polarized RE subdomains. MDCKT cells expressing FcLR(5-22) are labeled basolaterally with Tfn (green) and apically with anti-FcLR(5-22). 3D reconstructions of typical cells are shown (A) 1 d, (B) 2 d, (C) 3 d, and (D) 4 d after plating. Insets are magnified views of boxed regions in each frame. Yellow is overlap of the two markers. Bars, 10 μm.

Clathrin Adaptor μ1-B Is Not Responsible for Subdomain Formation

In the RE, basolateral cargo is enriched in transport vesicles that interact with the clathrin adapter AP-1B (Gan et al., 2002; Ang et al., 2004). The cytoplasmic tail of TfnR and tyrosine-dependent basolateral sorting motifs of other proteins are known to interact with the μ-1B clathrin adapter subunit for the delivery of biosynthetic products from the Golgi and endosomes to the basolateral domain. To test if this interaction is also responsible for the formation of RE subdomains, we infected LLC-PK1 (porcine kidney) cells (lacking μ1-B) with both Adeno-TfnR and Adeno-FcLR(5-22) and again visualized their localization. Two variants of the cell line were used. The first (LLC-PK1::μ1-A) stably expresses μ1-A (functional in Golgi to endosome/lysosome traffic) but lacks μ1B and thus cannot correctly deliver basolateral cargo. The second cell line (LLC-PK1::μ1-B) stably expresses μ1-B and supports delivery of basolateral proteins, including TfnR, to the basolateral domain (Folsch et al., 1999). Both cell types were grown on Transwell filter inserts, and labeled apically with red anti-FcLR(5-22) and basolaterally with green Tfn at 4°C. Control experiments demonstrated negligible leakage of the label across the membrane during labeling (unpublished data). Surprisingly, after a 25-min chase at 37°C the REs in both LLC-PK1::μ1-A and LLC-PK1::μ1-B cells displayed distinct apical and basolateral subdomains (Figure 7, A and B). The subdomains appeared somewhat better organized in the LLC-PK1::μ1-B cells (Figure 7B) than in the control cells. These results suggest that recruitment of basolateral proteins by clathrin adaptor μ subunits is not responsible for subdomain formation, although it leaves open the attractive possibility that apical and basolateral transport vesicles may be selectively formed at each subdomain, as suggested by the appearance of separate AP-1A and AP-1B domains (Folsch et al., 2003).

Figure 7.

AP-1B is not required for subdomain formation. LLC-PK1 cells lacking the AP-1B adaptor component μ1-B, were stably transfected with μ1-A (A) or μ1-B (B). Cells were labeled apically with anti-FcLR(5-22) (red) and basolaterally with Tfn (green). Arrows indicate representative subdomains. Inset is enlarged RE. Pictures are 3D reconstructions of 30 confocal sections. Triple arrows indicate rotation of axes. Bars, 10 μm.

What Does Direct Formation of RE Subdomains?

Rab11a has been suggested to localize to a transferrin-depleted apical compartment in polarized cells (Brown et al., 2000b). Given that our data suggest that RE subdomains are also a special feature of polarized cells, we used our experimental system to examine if Rab11a colocalizes with the apical RE subdomains. We were surprised to find that, whereas the bulk of Rab11a localized to the apical side of the cell, most of the Rab11a did not colocalize with REs at all (Figure 8A) but rather appeared to be in the apical cytoplasm. We examined Rab11a distribution further by using cells depleted of cytoplasm (using saponin treatment to extract cytoplasm before fixation) and then digitally subtracting any remaining Rab11a that did not colocalize with either apical or basolateral markers. Initial studies indicated that, while Rab11a did partially colocalize with apical RE subdomains, it colocalized more extensively with the areas of overlap between the apical and basolateral subdomains. This finding suggests a role in transport from the EEs rather than in organizing RE subdomains (Figure 8B). The results of further studies examining colocalization of Rab25 with the RE subdomains mirrored those for Rab11a (unpublished data). Virally introduced Rab8 also failed to show significant overlap with either RE subdomain (unpublished data).

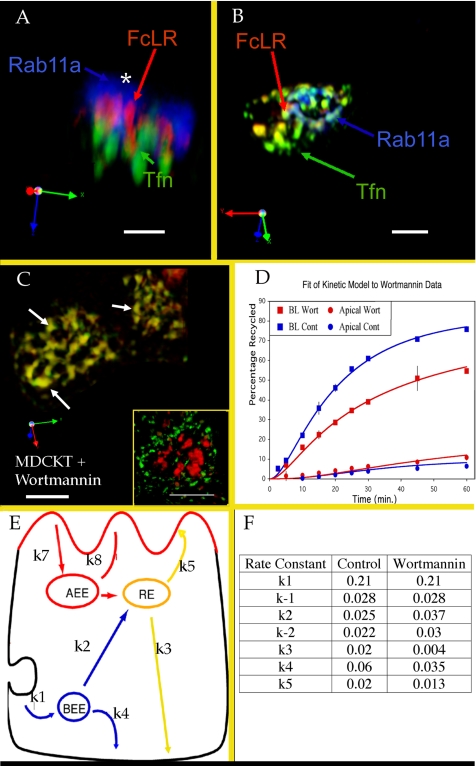

Figure 8.

Subdomain formation is not Rab11a dependent but is wortmannin sensitive. (A) 3D reconstruction of a single typical MDCKT cell apically labeled with anti-FcLR(5-22) (red), basolaterally with Tfn (green) by immunofluorescence for Rab11a (blue). Asterisk indicates largely cytosolic pool of Rab11a. (B) 3D reconstruction of a typical triple-labeled cell as in A, but treated with saponin on ice before fixation, and with the cytosolic component of Rab11a (which does not overlap with either a basolateral or apical cargo marker) removed from the digital reconstruction. (C) wortmannin-treated REs in two MDCKT cells labeled with Tfn (green) and anti-FcLR(5-22) (red). White arrows indicate example REs. Inset shows 3D reconstruction of wortmannin treated MDCKT cell labeled with Tfn for 2.5 min (green) or 25 min (red). (D) Kinetic analysis of wortmannin effect on Tfn recycling. Control basolateral recycling (upper blue squares, line), control transcytosis (lower blue circles, line), basolateral recycling in the presence of wortmannin (upper red squares, line) and transcytosis in the presence of wortmannin (lower red circles, line). Data points represent an average of six experiments. Error bars, 1 SD. Lines are curves fit from the mathematical model to the data. (E) Cartoon of the mathematical model. Rate constants are shown. Note that k−1 represents Tfn returned to the surface without ever passing through an acidified endosome, whereas k4 represents Tfn that has passed through EEs and is released upon reaching the cell surface. (F) Values derived for each rate constant. Internalization rates (k1, k−1) were determined directly as surface clearance of acid-strippable counts from the basolateral surface (separate unpublished data, n = 3). Note changes in EE and RE to plasma membrane rates.

Recent reports have shown that the apical plasma membrane is enriched in phosphatidylinositol [4,5] bisphosphate, whereas the basolateral plasma membrane is enriched in phosphatidylinositol [3,4,5] trisphosphate (PIP3) (Gassama-Diagne et al., 2006; Martin-Belmonte et al., 2007). We thus postulated that the subdomains may be organized around PIP3 in lipid domains and that this helps to segregate apical and basolateral cargoes in REs (Tuma et al., 2001). In fully polarized MDCK cells, PI(3)-kinase is found in both apical and basolateral EEs, where PI3P is associated with EEA-1– and Rab5-mediated fusion of endocytic vesicles (Simonsen et al., 1998; Gillooly et al., 2000, 2003; Stenmark and Gillooly, 2001). However, apical and basolateral EEs utilize this mechanism differently as depletion of PI3P results in dissociation of EEA1 from basolateral but not apical EEs (Tuma et al., 2001). As the role of PI-3 kinases in REs is unknown, we treated MDCKT cell expressing FcLR(5-22) with the PI3 Kinase inhibitor wortmannin at 50 nM during the uptake period. This dose inactivates the p85/p110 PI3 Kinase and has been shown to interfere with endosomal traffic but not to depolarize cells (Li et al., 1995; Tuma et al., 1999; van Dam et al., 2002). Cells were labeled with apical and basolateral ligands as in the other experiments, and endosomes were defined as REs based on timing of labeling and perinuclear positioning. Although wortmannin treatment did alter the morphology of the REs, it did not change the timing of Tfn passage through EEs and REs (Figure 8C, inset), allowing us to identify the RE using a timed pulse of Tfn. However, wortmannin treatment did abolish subdomains in the RE (Figure 8C). There was no detectable difference resulting from the timing of wortmannin application (pretreatment for 30 min vs. application only during the 25-min chase period; not shown). To further study this effect of wortmannin treatment, we performed a kinetic analysis of Tfn trafficking in the presence of this drug, after a single Tfn pulse through the entire endocytic system (for details on the kinetic analysis see Sheff et al., 1999). Consistent with the loss of sorting-dependent subdomains under these conditions, the recycling rate of Tfn was reduced in the wortmannin-treated cells (Figure 8D). Mathematical modeling of the recycling system using these data allowed us to measure flux as first-order rate constants along sorting pathways (Figure 8, D and E, inset). These results suggested a fivefold decrease in the flow of Tfn from the RE to the basolateral surface and a twofold decrease in the flow of Tfn from the EE to the basolateral surface. These findings are consistent with Tfn passage through both EEs and REs as separate organelles in our system but with a greater effect at REs. This suggests a role for lipid signaling in sorting down the basolateral pathway from REs. They are also consistent with the reported slowing of both rapid and slow phases of Tfn recycling in endosomes reported elsewhere (Spiro et al., 1996). As our assay does not visualize LE traffic, we were unable to determine if there were changes along the EE to LE pathway. Because many proteins, such as AKT and EEA-1, interact with products of the PI-3 Kinase, the possibility that some of these proteins and lipids remain associated with the basolateral cargo in the RE, and may help form a basolateral subdomain, is an attractive one.

DISCUSSION

Polarized cells divide their plasma membranes into apical and basolateral domains. Within those domains, subdomains are formed by different processes including clathrin coated pits, caveoli, and lipid rafts, all of which sequester different groups of proteins. Sonnichson et al. (2000) were the first to demonstrate that EEs also contain subdomains and that these are characterized by the presence of Rab5, Rab4, and Rab11a. Effector proteins bridge these domains and allow passage of cargo from one domain to another (De Renzis et al., 2002). Functionally, Rab5 domains provide fusion sites for inbound traffic. Despite tantalizing hints, specific functions for the Rab4 and Rab11a domains have never been established. Similar subdomains have been observed in LEs, and these are governed by Rab7 and Rab9 (Barbero et al., 2002). We wondered if similar subdomains also exist in REs.

Our use of basolateral human transferrin receptor and apical FcLR(5-22) as markers of apical endocytosis and recycling was inspired by previous work based on 2D images, in which these two markers colocalized but were often associated with endosomes containing one or the other construct (Sheff et al., 1999). We therefore used confocal microscopy to generate a 3D stack of images spanning the cell height. By rotating the 3D image, it was possible to observe that the endosomal regions containing both markers were physically attached to the regions containing only one or the other marker (Figure 1). This observation suggested that REs do indeed have subdomains and that these are functionally defined by the presence of apical or basolateral proteins. Application of both ligands to the entire cell surface of a primary cell line, as was done with isolated primary rat hippocampal neurons transfected with FcLR(5-22), still resulted in segregation within REs, suggesting that subdomain segregation is a function common to the REs of polarized cells.

Because these are morphological studies, we also took care to examine live cells to rule out a fixation artifact, and observed the same pattern of subdomains. Sodium butyrate induction is particularly useful for expressing TfnR in our MDCK cells. However, this treatment has been observed to alter the morphology of MDCK cells (Fiorino and Zvibel, 1996). In these experiments, sodium butyrate treatment does not appear to affect the formation of RE subdomains based on three lines of evidence: 1) FcLR(5-22)/Tfn subdomains were still observed in MDCK cells without butyrate treatment. Similarly, wheat germ agglutinin/LDLR subdomains were observed without butyrate treatment. 2) Subdomains were observed in MDCKT cells treated with butyrate only on day 3 and day 4. Butyrate treatment did not result in subdomain formation on day 1 or day 2. 3) Subdomains were not visualized in nonpolarized cells even after butyrate treatment. Together these studies suggest that subdomains are a genuine feature of the polarized RE and not an artifact of either fixation or butyrate treatment.

The fact that RE-based segregation of ligands failed to occur in nonpolarized CHOT and HeLa cell lines implies that the REs of nonpolarized cells do not have cognate apical and basolateral pathways that end in a single plasma membrane domain as had previously been suggested (Yoshimori et al., 1996; Harder et al., 1998). Supporting this notion further is the fact that Rab11a, which is a reliable RE marker in nonpolarized cells, labels only a subset of REs in polarized cells (our unpublished data and Goldenring et al., 1996; Ullrich et al., 1996). These results suggest that the perinuclear RE of nonpolarized cells is not an exact cognate of the RE in polarized cells, although both receive membrane from EEs and both participate in endocytic recycling.

The clathrin adaptor subunit μ1-B is present in the REs of polarized but not nonpolarized cells and is required for the polarized delivery of basolateral proteins with tyrosine-based sorting determinants (Folsch et al., 1999, 2003). However, here we note that subdomains arise even in the REs of LLC-PK1 porcine kidney cells, in spite of the fact that they lack μ1-B and are incapable of basolateral delivery of the TfnR. Furthermore, these same cells are capable of polarized delivery when μ1-B is restored (Folsch et al., 1999). Together with the results described above, this finding suggests that distinctions between polarized and nonpolarized REs include differences in sorting functions, Rab protein recruitment and adapter protein recruitment. Importantly, these results suggest that two separate layers of sorting are involved at the RE. The first is the segregation of apical and basolateral proteins, and the second entails interactions with the clathrin adapter subunits and the incorporation of proteins into transport vesicles. It may also explain the exquisite selectivity of REs to basolateral membrane traffic. If RE sorting into subdomains is even 70% effective and inclusion into transport vesicles through μ1-B is also only 70% selective, then the overall level of mis-sorting would be only 9%, which is close to the 7% mis-sorting observed in quantitative assays of basolaterally applied Tfn. This concept of dual-level sorting is further supported by the finding that AP-1 transport vesicles containing μ1-A and μ1-B are nonoverlapping and serve distinct functions (Folsch et al., 2001, 2003). Polarized transport vesicles formed by specific adapter proteins may thus form specifically from presorted subdomains of the RE.

Taking these observations a step further, we found that polarized subdomains form in the RE as cell polarity develops over a 4-d period. This finding suggests that polarity within the subdomain is intricately linked to the development of polarity at the plasma membrane. Importantly, the fact that the RE did not retain polarized subdomains after cell passaging indicates that the RE does not retain a “memory” of polarized sorting for the cell. Instead, polarization within this organelle must be reassembled as it is for the cell.

Our results are based on the interpretations of images of fixed cells, which made it difficult to determine whether the observed RE subdomains were the result of traffic from apical or basolateral domains clustering and entering at a specific sites, or the result of traffic being sorted for polarized exit from the RE. We approached this question in two ways. First, differently labeled Tfns were applied to the apical and basolateral sides of the same MDCKT cells along with the anti-FcLR(5-22) apical recycling marker. If subdomains were the result of fusion into the RE, then the apical Tfn should have colocalized with the apical FcLR(5-22). If they were the result of protein sorting within the RE, then apically applied Tfn should have colocalized with basolaterally applied Tfn. Our finding that apically applied Tfn colocalized with basolateral Tfn and segregated from apically applied FcLR(5-22) supports the hypothesis that RE subdomains form as a result of an active sorting process within the RE. As a second approach, we applied both anti-NgCAM and Tfn basolaterally and anti-FcLR(5-22) apically. As described elsewhere, basolateral NgCAM is a basolateral to apical transcytotic protein (Anderson et al., 2005). Nevertheless, we found that the basolaterally applied anti-NgCAM colocalized with the apically applied anti-FcLR(5-22) and segregated from the basolaterally applied Tfn (Figure 4). Taken together these results demonstrate that apical and basolateral RE subdomains form as a result of sorting according to the destination of the cargo molecule.

If REs sort apical and basolateral proteins into separate subdomains, how is this accomplished at the molecular level? Our LLC-PK1 studies effectively ruled out an association of basolateral proteins with clathrin μ-1B adaptors as the basis for RE subdomain segregation, and this was supported by the fact that μ-1B expression in CHOT cells did not produce subdomains in these nonpolarized cells (unpublished data).

The alternative hypothesis that ligand segregation at the REs could merely be kinetic, with basolateral traffic passing through exit zones faster and leaving behind apically enriched subdomains was ruled out by the experiments in which cells treated with AlF4− (which effectively blocks basolateral exit from the REs) maintained subdomains (Figure 5). If subdomain formation were a kinetic phenomenon, this treatment should instead have abolished subdomain formation. Similarly, in the experiments shown in Figure 3, the cells were labeled both on ice and at 37°C, with anti-FcLR(5-22), apical, and basolateral Tfns. They were then chased for 25 min. This is sufficient time to label the entire recycling system. Because the apically labeling antibody is not released after recycling, the apical pathway was saturated throughout the experiment under these conditions. If subdomain formation were due to faster depletion of the apical cargo from REs, then subdomains would have been eliminated under these conditions. As in the AlF4− experiments, however, subdomains were maintained. Taken together, these triple-labeling experiments demonstrate that cargo segregation in the REs is not the result of a kinetic effect on ligand clearance.

Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11a have been implicated in the formation or at least have been shown to localize to distinct EE subdomains. We tested for colocalization of Rab11a and Rab8 with apical and basolateral subdomains, respectively. Unlike the situation in nonpolarized cells, in MDCKT cells, Rab11a (both GFP-Rab11a and endogenous) only partially colocalized with the REs, as has been reported by others (Goldenring et al., 1996; Leung et al., 2000; Hoekstra et al., 2004). Although we observed Rab11a to be confined to the apical pole of the cell, our study is unique in that the majority of Rab11a was not associated with cargo-containing REs. Instead, endosomally associated Rab11a appeared to localize to the region of overlap between apical and basolateral zones. The reason for this discrepancy with previous publications may relate to differences in image analysis or cargo loading techniques, and it remains unclear which is a more accurate reflection of physiological conditions. In any case, the result does suggest that Rab11a is not responsible for apical subdomain formation. In retrospect, this is not so surprising as Rab11a is also found in nonpolarized cells, which do not possess subdomains. If Rab11a were the basis for apical subdomain formation, one would expect such subdomains to be present in all cells that contain it. Studies with Rab8 failed to demonstrate specific colocalization of Rab8 with the basolateral subdomain.

Because Rab5 recruits PI3 kinase in EEs, sorting could be based to some extent on lipid composition. Proteins recruited to PI3P domains could potentially remain with the associated vesicle, or PI3P could be converted to PI3,5P2 or PI3,4,5P3, to then recruit domain-forming proteins. Wortmannin treatment virtually abolished apical and basolateral subdomains in REs (Figure 8). Tfn recycling from the RE to the basolateral plasma membrane was also strongly inhibited. These results are similar to those obtained by Spiro et al. (1996), who observed inhibition of both the rapid and slow phases of Tfn recycling. PIP3 is enriched in the basolateral plasma membrane and there serves as a targeting signal for basolateral traffic. Perhaps PI-3 Kinase products in the RE (including PIP3) likewise mark basolateral subdomains. Although a tempting hypothesis, elucidating these details will have to await further work.

The RE has been proposed as a storage site for plasma membrane lipids and proteins. It is the source of AMPA receptors for long-term potentiation and of membrane for dendritic spines. However, sorting from the RE in these systems has been assumed to be dependent on specific inclusion into transport vesicles, with the RE itself playing a passive role. Here we propose that the RE is an active sorting organelle, segregating apical and basolateral membrane proteins using cues derived from the lipids in which those membranes are embedded. As such, the RE would greatly enhance the sorting accuracy of the recycling system and play a much more active role than previously appreciated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ira Mellman and Graham Warren for discussions and advice when results seemed far away. This work was supported in part by grants to D.S. from the American Heart Association (0335078N) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institution (53000250). Support to E.A. in the laboratory of Ira Mellman was provided by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and the American Cancer Society (Research Scholar Grant PF-01-092-01-CSM). This work was supported in part by Grant RO1NS 045969 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to B.W. We thank the Seldon Company for use of their database software and to Improvision for providing Velocity software. Finally, many thanks to B. Foellmer, Sine Qua Non.

Abbreviations used:

- Tfn

transferrin

- TfnR

transferrin receptor

- FcLR

Fc ectodomain fused to low-density-lipoprotein receptor cytoplasmic domain

- EE

early endosome

- RE

recycling endosome

- MDCKT

MDCK cells stably transfected with human transferrin receptor

- CHOT

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human Tfn receptor.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0873) on May 9, 2007.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

REFERENCES

- Anderson E., Maday S., Sfakianos J., Hull M., Winckler B., Sheff D., Folsch H., Mellman I. Transcytosis of NgCAM in epithelial cells reflects differential signal recognition on the endocytic and secretory pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:595–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang A. L., Taguchi T., Francis S., Folsch H., Murrells L. J., Pypaert M., Warren G., Mellman I. Recycling endosomes can serve as intermediates during transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane of MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:531–543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbero P., Bittova L., Pfeffer S. R. Visualization of Rab9-mediated vesicle transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:511–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besterman J. M., Low R. B. Endocytosis: a review of mechanisms and plasma membrane dynamics. Biochem. J. 1983;210:1–13. doi: 10.1042/bj2100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomsel M., Parton R., Kuznetsov S. A., Schroer T. A., Gruenberg J. Microtubule- and motor-dependent fusion in vitro between apical and basolateral endocytic vesicles from MDCK cells. Cell. 1990;62:719–731. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90117-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J. S., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Coat proteins: shaping membrane transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitfeld P. P., Casanova J. E., Simister N. E., Ross S. A., McKinnon W. C., Mostov K. E. Sorting signals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1989;1:617–623. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90024-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. S., Wang E., Areoti B., Chapin S. J., Mostov K. E., Dunn K. E. Definition of distinct compartments in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells for membrane-volume sorting, polarized sorting and apical recycling. Traffic. 2000a;1:124–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. S., Wang E., Aroeti B., Chapin S. J., Mostov K. E., Dunn K. W. Definition of distinct compartments in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells for membrane-volume sorting, polarized sorting and apical recycling. Traffic. 2000b;1:124–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Renzis S., Sonnichsen B., Zerial M. Divalent Rab effectors regulate the sub-compartmental organization and sorting of early endosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;14:14. doi: 10.1038/ncb744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drubin D. G., Nelson W. J. Origins of cell polarity. Cell. 1996;84:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorino A. S., Zvibel I. Disruption of cell-cell adhesion in the presence of sodium butyrate activates expression of the 92 kDa type IV collagenase in MDCK cells. Cell Biol. Int. 1996;20:489–499. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H. The building blocks for basolateral vesicles in polarized epithelial cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H., Ohno H., Bonifacino J. S., Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells [see comments] Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H., Pypaert M., Maday S., Pelletier L., Mellman I. The AP-1A and AP-1B clathrin adaptor complexes define biochemically and functionally distinct membrane domains. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:351–362. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H., Pypaert M., Schu P., Mellman I. Distribution and function of AP-1 clathrin adaptor complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:595–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouraux M. A., Deneka M., Ivan V., van der Heijden A., Raymackers J., van Suylekom D., van Venrooij W. J., van der Sluijs P., Pruijn G. J. Rabip4′ is an effector of rab5 and rab4 and regulates transport through early endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:611–624. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter C. E., Connolly C. N., Cutler D. F., Hopkins C. R. Newly synthesized transferrin receptors can be detected in the endosome before they appear on the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10999–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter C. E., Gibson A., Allchin E. H., Maxwell S., Ruddock L. J., Odorizzi G., Domingo D., Trowbridge I. S., Hopkins C. R. In polarized MDCK cells basolateral vesicles arise from clathrin-gamma-adaptin-coated domains on endosomal tubules. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:611–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Y., McGraw T. E., Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial-specific adaptor AP1B mediates post-endocytic recycling to the basolateral membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:605–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassama-Diagne A., Yu W., Ter Beest M., Martin-Belmonte F., Kierbel A., Engel J., Mostov K. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate regulates the formation of the basolateral plasma membrane in epithelial cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/ncb1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R. N., Maxfield F. R. Evidence for nonvectorial, retrograde transferrin traffic in the early endosomes of HEp2 cells. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:549–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillooly D. J., Morrow I. C., Lindsay M., Gould R., Bryant N. J., Gaullier J. M., Parton R. G., Stenmark H. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillooly D. J., Raiborg C., Stenmark H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is found in microdomains of early endosomes. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2003;120:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s00418-003-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenring J. R., Smith J., Vaughan H. D., Cameron P., Hawkins W., Navarre J. Rab11 is an apically located small GTP-binding protein in epithelial tissues. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:G515–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.3.G515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J., Griffiths G., Howell K. E. Characterization of the early endosome and putative endocytic carrier vesicles in vivo and with an assay of vesicle fusion in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:1301–1316. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Penman M., Trigatti B. L., Krieger M. A single point mutation in epsilon-COP results in temperature-sensitive, lethal defects in membrane transport in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:11191–11196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder T., Scheiffele P., Verkade P., Simons K. Lipid domain structure of the plasma membrane revealed by patching of membrane components. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:929–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra D., Tyteca D., van IJzendoorn S. C. The subapical compartment: a traffic center in membrane polarity development. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2183–2192. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins C. R., Gibson A., Shipman M., Strickland D. K., Trowbridge I. S. In migrating fibroblasts, recycling receptors are concentrated in narrow tubules in the pericentriolar area, and then routed to the plasma membrane of the leading lamella. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:1265–1274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins C. R., Trowbridge I. S. Internalization and processing of transferrin and the transferrin receptor in human carcinoma A431 cells. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:508–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight A., Hughson E., Hopkins C. R., Cutler D. F. Membrane protein trafficking through the common apical endosome compartment of polarized Caco-2 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1995;6:597–610. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto U. M., Hubbard A. L., Mellman I. A novel cellular phenotype for familial hypercholesterolemia due to a defect in polarized targeting of LDL receptor. Cell. 2001;105:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld S., Mellman I. The biogenesis of lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1989;5:483–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.002411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S. M., Ruiz W. G., Apodaca G. Sorting of membrane and fluid at the apical pole of polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:2131–2150. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.6.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., D'Souza-Schorey C., Barbieri M. A., Roberts R. L., Klippel A., Williams L. T., Stahl P. D. Evidence for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase as a regulator of endocytosis via activation of Rab5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10207–10211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F., Gassama A., Datta A., Yu W., Rescher U., Gerke V., Mostov K. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K., Hunziker W., Mellman I. Basolateral sorting of LDL receptor in MDCK cells: the cytoplasmic domain contains two tyrosine dependent targeting determinants. Cell. 1992;71:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90551-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K., Mellman I. Mechanisms of cell polarity: sorting and transport in epithelial cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1994;6:545–554. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K., Whitney J. A., Miller E., Mellman I. Common signals control LDL receptor sorting in endosomes and the Golgi of MDCK cells. Cell. 1993;74:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90727-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I. Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;12:575–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I. Quo vadis: polarized membrane recycling in motility and phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:529–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I., Yamamoto E., Whitney J. A., Kim M., Hunziker W., Matter K. Molecular sorting in polarized and non-polarized cells—common problems, common solutions. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 1993;17:1–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1993.supplement_17.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S., Maxfield F. R. Role of membrane organization and membrane domains in endocytic lipid trafficking. Traffic. 2000;1:203–211. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. J. Epithelial cell polarity from the outside looking in. News Physiol. Sci. 2003;18:143–146. doi: 10.1152/nips.01435.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G., Trowbridge I. S. Structural requirements for basolateral sorting of the human transferrin receptor in the biosynthetic and endocytic pathways of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1255–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H., Fournier M., Poy G., Bonifacino J. S. Structural determinants of interaction of tyrosine based sorting signals with the adaptor medium chains. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:29009–29015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Penick E. C., Edwards J. G., Kauer J. A., Ehlers M. D. Recycling endosomes supply AMPA receptors for LTP. Science. 2004;305:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1102026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris R., Foletti D. L., Scheller R. H. Dynamics of tubulovesicular recycling endosomes in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10324–10337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10324.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris R., Klumperman J., Scheller R. H. A Rab11/Rip11 protein complex regulates apical membrane trafficking via recycling endosomes. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheff D. R., Daro E. A., Hull M., Mellman I. The receptor recycling pathway contains two distinct populations of early endosomes with different sorting functions. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:123–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheff D. R., Kroschewski R., Mellman I. Actin dependence of polarized receptor recycling in Madin-Darby canine kidney cell endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:262–275. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen A., Lippe R., Christoforidis S., Gaullier J. M., Brech A., Callaghan J., Toh B. H., Murphy C., Zerial M., Stenmark H. EEA 1 links PI(3)K function to Rab 5 regulation of endosome fusion. Nature. 1998;394:494–498. doi: 10.1038/28879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B., De Renzis S., Nielsen E., Rietdorf J., Zerial M. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro D. J., Boll W., Kirchhausen T., Wessling-Resnick M. Wortmannin alters the transferrin receptor endocytic pathway in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:355–367. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H., Gillooly D. J. Intracellular trafficking and turnover of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;12:193–199. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuma P. L., Finnegan C. M., Yi J. H., Hubbard A. L. Evidence for apical endocytosis in polarized hepatic cells: phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors lead to the lysosomal accumulation of resident apical plasma membrane proteins. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1089–1102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuma P. L., Nyasae L. K., Backer J. M., Hubbard A. L. Vps34p differentially regulates endocytosis from the apical and basolateral domains in polarized hepatic cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:1197–1208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukkonen P., Lewis V., Marsh M., Helenius A., Mellman I. Transport of macrophage Fc receptors and Fc receptor-bound ligands to lysosomes. J. Exp. Med. 1986;163:952–971. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.4.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich O., Reinsch S., Urbe S., Zerial M., Parton R. G. Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam E. M., Ten Broeke T., Jansen K., Spijkers P., Stoorvogel W. Endocytosed transferrin receptors recycle via distinct dynamin and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:48876–48883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E., Brown P. S., Aroeti B., Chapin S. J., Mostov K. E., Dunn K. W. Apical and basolateral endocytic pathways of MDCK cells meet in acidic common endosomes distinct from a nearly-neutral apical recycling endosome. Traffic. 2000;1:480–493. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winckler B., Mellman I. Neuronal polarity: controlling the sorting and diffusion of membrane components [see comments] Neuron. 1999;23:637–640. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco D., Anderson E. D., Chang M. C., Norden C., Boiko T., Folsch H., Winckler B. Uncovering multiple axonal targeting pathways in hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1317–1328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimori T., Keller P., Roth M. G., Simons K. Different biosynthetic transport routes to the plasma membrane in BHK and CHO cells. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:247–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.