Abstract

Two types of tetracycline-controlled inducible RNAi expression systems have been developed that generally utilize multiple tetracycline operators (TetOs) or repressor fusion proteins to overcome the siRNA leakiness. Here, we report a novel system that overexpresses the tetracycline repressor (TetR) via a bicistronic construct to control siRNA expression. The high level of TetR expression ensures that the inducible promoter is tightly bound, with minimal basal transcription, allowing for regulation solely dependent on TetR rather than a TetR fusion protein via a more complicated mechanism. At the same time, this system contains only a single TetO, thus minimizing the promoter impairment occurring in existing systems due to the incorporation of multiple TetOs, and maximizing the siRNA expression upon induction. In addition, this system combines all the components required for regulation of siRNA expression into a single lentiviral vector, so that stable cell lines can be generated by a single transduction and selection, with significant reduction in time and cost. Taken together, this all-in-one lentiviral vector with the feature of TetR overexpression provides a unique and more efficient tool for conditional gene knockdown that has wide applications. We have demonstrated the high degree of robustness and versatility of this system as applied to several mammalian cells and xenograft animals.

Keywords: inducible siRNA, gene regulation, leakiness, promoter impairment, xenograft animal

INTRODUCTION

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are 21– 23 base-pair (bp) double-stranded RNA molecules that can be used to elicit gene-specific silencing in mammalian cells (Hannon and Rossi 2004; Meister and Tuschl 2004; Mello and Conte 2004; Zamore and Haley 2005; Moffat and Sabatini 2006). Such RNA interference (RNAi) can be achieved by transfecting cells with siRNAs that are synthesized in vitro (Calegari et al. 2002; Donze and Picard 2002; Yang et al. 2004) or by siRNA expression in vivo from expression vectors, an approach that can be used to stably express siRNAs in cell lines (Brummelkamp et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2002; Miyagishi and Taira 2002; Sui et al. 2002; Xia et al. 2002; Tran et al. 2003; Zheng et al. 2004). Currently, most siRNA expression vectors are engineered to drive siRNA transcription from the polymerase III promoters U6 and H1. These promoters are particularly suited for hairpin siRNA (shRNA) expression, since they contain all of the cis-acting promoter elements upstream of the transcription initiation site (Paule and White 2000) and deploy a polyT transcription termination site that leads to the addition of 2-nucleotide (nt) overhangs (UU) to shRNAs, a feature that is important for siRNA function. However, specific inhibition of gene expression using a stably integrated siRNA (Barton and Medzhitov 2002; Devroe and Silver 2002; Tiscornia et al. 2003; Qin et al. 2003) is not suitable for silencing genes that are involved in cell growth or survival (Zhou et al. 2006). In such cases, regulating siRNA expression in mammalian cells has become essential. Having the ability to control when and how much of a particular siRNA is expressed makes it possible to study temporal- and concentration-dependent effects on a host system and allow cells to grow prior to gene silencing by “toxic” siRNAs. Furthermore, studying a host cell's response to the presence and absence of siRNA often leads to further understanding of the target gene's function.

The inducible RNAi system uses a modified form of the regulated, tetracycline-controlled gene expression system described by Gossen and Bujard (2002) in mammalian cells for the purpose of temporal silencing target genes. This system relies on two components: a tetracycline regulatory protein (TetR), which has affinity to the tetracycline operator (TetO); and a TetO-tethered pol III promoter, whose transcription activity is blocked by binding to the regulatory TetR. In the absence of tetracycline (Tet), the TetR protein binds to the TetO sequence within the promoter and acts as a potent transcription suppressor. The siRNA expression is restored when the cell culture medium is added with either Tet or doxycycline (Dox), a Tet derivative, which binds to and causes dissociation of TetR from the pol III promoter via a TetR conformation change (Zhou et al. 2006). This system allows for observation of the loss-of-function phenotypes under noninduced and induced conditions in the same isogenic cells, excluding other potential interferences.

Several groups have developed this inducible system that generally includes two plasmids, a TetR-containing DNA vector and a Tet-responsive pol III promoter-harboring vector, which were sequentially transfected into target cells to create a double-stable cell line wherein TetR is constitutively expressed and the siRNA is conditionally expressed from the Tet-responsive promoter (Czauderna et al. 2003; Matsukura et al. 2003; van de Wetering et al. 2003; Wiznerowicz and Trono 2003). However, this system is extremely time consuming, usually requiring months, for the selection of double-stable cell lines from large-scale clone screenings. Another major issue is siRNA leakiness in the absence of inducer, which usually results in significant suppression of the target gene even with a little siRNA expression. The most direct method overcoming the leakiness is to express a high level of TetR in host cells to ensure 100% occupancy of the regulatory sites within the inducible promoter. But this is extremely difficult to attain, and so far no successful example has ever been reported. Instead, some groups have introduced multiple TetO sequences into the pol III promoter so as to recruit TetR more efficiently to the inducible promoter (Matsukura et al. 2003; van de Wetering et al. 2003; Wiznerowicz and Trono 2003). Alternatively, some groups have replaced the TetR protein with a TetR fusion protein to increase its affinity to the inducible promoter (Amar et al. 2006; Szulc et al. 2006). However, introduction of multiple TetO sequences into a pol III promoter usually impairs or ruins its transcription efficiency, depending on the locations of the TetO sequences in the promoter (Chen et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2004). A TetR fusion protein may potentially bring other uncertainties and even disturbances to the inducible system, making the mechanism more complicated.

Here, we report the first establishment of a direct Tet-off inducible siRNA expression system that combines the Tet-responsive U6 promoter, the TetR gene, and a puromycin selection marker in a single lentiviral vector, which converts the time-consuming multiple selection processes into just a single selection. More importantly, this system achieved an extremely high level of TetR expression from an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) bicistronic cassette (Rees et al. 1996), wherein the antibiotic resistance gene is downstream from the TetR gene. Such a high level of TetR expression not only efficiently suppressed the inducible promoter with minimal basal transcription but also made the regulation solely dependent on TetR steric hindrance rather than a fusion protein via a more complicated mechanism. In addition, this system minimized the promoter impairment by incorporation of just a single TetO instead of multiple TetOs into the promoter that maintains ∼80% of wild-type promoter transcription efficiency (Matsukura et al. 2003; van de Wetering et al. 2003; Wiznerowicz and Trono 2003) upon induction. Currently, this all-in-one inducible siRNA lentiviral vector has been developed as a universal tool to regulate siRNA expression for studying loss-of-function phenotypes in dividing and nondividing cells as well as in xenograft animal models (Ke et al. 2006).

RESULTS

Introduction of multiple TetOs into the U6 promoter impaired its transcription efficiency

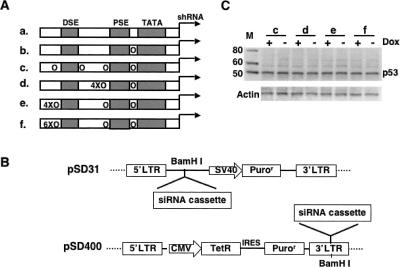

The major issue for inducible siRNA systems is its leakiness, as has been reported in several studies (Chen et al. 2003; Czauderna et al. 2003; Matsukura et al. 2003; van de Wetering et al. 2003; Wiznerowicz and Trono 2003; Lin et al. 2004; Amar et al. 2006; Szulc et al. 2006), when a single TetO was engineered into the U6 promoter to control the formation of the transcription initiation complex. To address this issue, we have tried to insert multiple copies of TetO into the U6 promoter (Fig. 1A) in an attempt to recruit as many TetR molecules as possible for binding to the U6 promoter. However, multiple TetO sequences in the U6 promoter abolished transcriptional activity (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with previous reports that multiple TetO sequences could decrease transcriptional activity to different extents depending on their location in the U6 promoter (Chen et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2004). These results suggested that each TetO modification, applied neither to the TATA box nor to the proximal sequence element (PSE), brings marginal impairment of U6 transcription (Ohkawa and Taira 2000; Angela and Kunkel 2003), but overall modification with multiple TetOs into the promoter influences the promoter essential core unit for recruiting and forming the transcription initiation complex.

FIGURE 1.

The Tet-inducible siRNA expression system. (A) Schematics of the wild-type (a) and inducible mouse U6 promoters with one (b) or more copies of TetO sequences engineered around the TATA box, PSE, and DSE regions (c–f). (B) Schematic representation of the lentivector pSD31 for constitutive siRNA expression and pSD400 for conditional siRNA expression. pSD31 was modified from the pHIV-7 vector by introducing a BamHI site downstream of the 5′ -LTR for the cloning variant siRNA expression cassette. pSD400 was modified from pSD31 by deletion of the SV40-Puror sequence and introduction of a BglII-CMV-TetR-IRES-Puror-BglII cassette at the BamHI site. In this cassette a CMV promoter drives the bicistronic expression unit comprising TetR and the antibiotic puromycine resistance gene through an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES). The inducible siRNA expression cassette is inserted at the 3′- LTR via a newly introduced BamHI site that replaced the original BglII site by mutagenesis. (C) Western blot analysis of p53 knockdown in MCF-7 cells by siRNAs expressed from multiple TetO-engineering inducible mouse U6 promoters (c–f). Those siRNA expression cassettes were stably transduced into MCF-7 cells via the lentivector pSD31. There was no apparent p53 knockdown in either the presence (+) or absence (−) of Dox, indicating that multiple TetOs in the U6 promoter ruined its transcription activity.

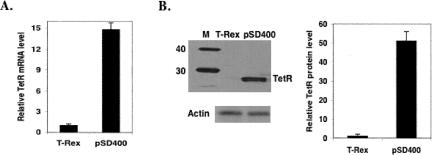

Overexpression of TetR in stable transduced cells with an integrated IRES bicistronic construct

In an effort to address the leakiness issue without the severe impairment of the TetO-engineered U6 promoter, we have tried to improve the expression level of TetR to ensure complete occupancy of the regulatory sites within the inducible promoter. We replaced the regular CMV-TetR expression cassette with a CMV-TetR-IRES-Puro expression cassette (Fig. 1B), which conferred an extremely high level of TetR when stably integrated into mammalian cells by puromycin selection (Fig. 2). As shown in Figure 2, A and B, compared with commercial T-Rex cells from Invitrogen, which were cultured in the presence of Blasticidin for maintaining TetR expression according to the manual protocol, the TetR expression level in MCF-7 cells stably transduced with the pSD400 lentivector was ∼15-fold higher at the mRNA level and ∼50-fold higher at the protein level.

FIGURE 2.

Taqman (A) and Western blot (B) analysis of TetR over-expression in stably transduced MCF-7 cells with the empty pSD400. The T-Rex cell line (Invitrogen) stably expresses TetR. Compared with T-Rex cells, the TetR expression in stably transduced MCF-7 cells was ∼15-fold higher on the mRNA level and ∼50-fold higher on the protein level.

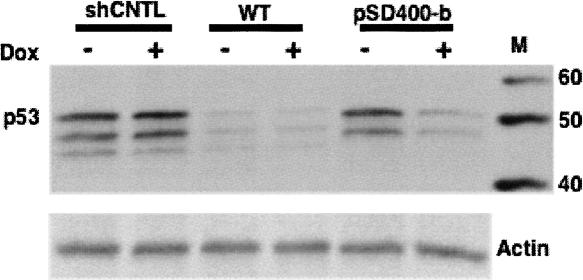

Tight regulation of siRNA expression from a single TetO-engineered mU6 inducible promoter

The constitutive and extremely high level of intracellular TetR in stable cells with the IRES cassette might be sufficient to completely occupy the regulatory TetO sequences within the inducible promoter and completely repress siRNA transcription. In order to evaluate this potentiality, we constructed an all-in-one inducible lentivector, pSD400-p53siRNA, by inserting a mU6-driving p53-siRNA expression cassette that contains a single TetO sequence between the TATA box and PSE region (Fig. 1A, “b”) into the pSD400 vector (Fig. 1B). Hereafter, unless otherwise noted, the inducible promoter refers to a single TetO-tethered mU6 promoter. MCF-7 cells were stably transduced with the pSD400-b vector and cultured in the presence or absence of Dox (1 mg/mL). For comparison, we also transduced the same cells in parallel with vector pSD31 bearing a wild-type (WT) mU6 cassette (Fig. 1A, “a”) with either p53 siRNA (WT or pSD31-a, positive control) or scrambled siRNA (CNTL, negative control). As shown in Figure 3, the WT vector caused nearly complete silencing of p53 expression at the protein level with or without Dox. In contrast, the pSD400-b vector had little if any effect on the level of p53 protein relative to the CNTL-transduced control cells in the absence of Dox, suggesting that there was minimal basal transcription of p53 siRNA. Addition of Dox caused a significant reduction in p53 protein expression, reaching a level almost similar to the WT-transduced cells. These results demonstrated that the combination of a high level of TetR protein with a single TetO-U6 promoter yielded tight regulation and maximum induction of siRNA.

FIGURE 3.

Western blot analysis of conditional siRNA expression against p53 in stably transduced MCF-7 cells cultured in the presence and absence of Dox (1 mg/mL). pSD31-p53siRNA (WT) was a constitutive siRNA expression vector with a wild-type mU6 promoter (Fig. 1A, a), serving as the positive control. pSD400-b was an inducible vector with a single TetO-modified mU6 promoter (Fig. 1A, b). pSD31-CTNLsiRNA (CNTL) was a negative control vector that constitutively expressed a scrambled siRNA. The pSD31-p53siRNA (WT) vector caused nearly complete silencing of p53 expression at the protein level in both the presence (+) and absence (−) of Dox. In the absence of Dox, the pSD400-b vector had little effect on p53, with its expression level at almost the same as that in negative control (CNTL) transduced cells. Addition of Dox caused a significant reduction in p53 protein expression by pSD400-b, reaching a level almost similar to that from the positive control cells. Here, actin was an internal protein for Western blot analysis.

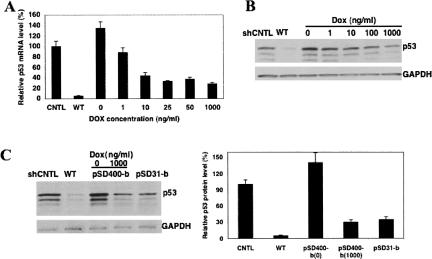

The dose dependence of Dox on siRNA expression in stably transduced MCF-7 cells

We analyzed the dose dependence of Dox on siRNA expression in MCF-7 cells stably transduced with the pSD400-b lentivector. We induced siRNA expression using Dox at concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 ng/mL. Three days after induction we performed Taqman and Western blot analysis of p53 mRNA and protein expression, respectively. The data are reported relative to the p53 mRNA level in nontransduced MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4A). Taqman analysis indicated that the transduced MCF-7 cells expressed ∼ 35% more p53 mRNA than the nontransduced cells, which should be kept in mind during normalization of gene regulation. The Taqman data showed that inducible siRNA expression is remarkably sensitive to Dox concentrations with EC50 of ∼5 ng/mL for p53 knockdown; even as little as 1 ng/mL Dox induced sufficient siRNA expression that significantly reduced p53 mRNA expression. Western blot analysis of p53 protein expression agreed well with the Taqman data (Fig. 4B). We also observed that p53 reduction induced by Dox at high concentration (>100 ng/mL) plateaued at ∼80%, less than ∼95% from the WT pSD31-a vector. The activity variation raised the question of whether the Dox concentration is saturated to neutralize all TetO-binding TetR. We have tried to increase Dox to 5000 ng/mL, which seemed to affect cell growth. We then compared the p53 knockdown by inducible vector with pSD31-b (Fig. 1). Due to the lack of TetR, the siRNA expression level from pSD31-b would be the maximum level from the inducible pSD400-b. We found that under 1000 ng/mL Dox, the p53 knockdown by pSD400-b was almost at the same extent as pSD31-b (Fig. 4C), suggesting that Dox concentration has been enough to neutralize all TetR. Therefore, the above knockdown variation should reflect the promoter impairment by the single TetO rather than TetR poor neutralization.

FIGURE 4.

Taqman (A) and Western blot (B) analysis of the dose dependence of Dox on siRNA induction and target gene p53 knockdown. The p53 mRNA levels in transduced MCF-7 with various concentrations of Dox were normalized to that from nontransduced MCF-7 cells. GAPDH is an internal control for Western blot analysis. (C) Comparison of p53 knockdown by wild-type vector pSD31-a, inducible vector pSD400-b, and a constitutive vector containing the inducible cassette pSD31-b. The p53 protein knockdowns were quantitatively normalized to negative control siRNA (CNTL).

The time courses of siRNA expression and repression upon Tet induction and withdrawal

We induced siRNA expression using 250 ng/mL Dox in MCF-7 cells stably transduced with the inducible p53 siRNA lentiviral vector for 0–8 d and analyzed p53 mRNA level by Taqman. As shown in Figure 5A, the p53 mRNA knockdown gradually increased, and at day 8 reached the maximum level with ∼80% reduction compared with noninduced MCF-7 cells. We also examined the effect of Dox withdrawal to verify that the knockdown was reversible. We induced siRNA expression for 8 d with 250 ng/mL Dox, and then replaced the medium with Tet-free medium and examined the p53 mRNA level by Taqman for 0–6 d. The mRNA level gradually restored following removal of Dox, and at day 6 was restored to the almost normal level (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that the siRNA expression in this system is inducible and reversible, and the kinetic process of gene knockdown and phenotype change could be followed up using this system.

FIGURE 5.

The time-courses of siRNA expression (A) and repression (B) upon Tet induction and withdrawal. The stably transduced MCF-7 cells were first allowed to grow for 1 wk in Tet-free medium and then Dox (250 ng/mL) was added to induce siRNA expression for 0–8 d. After Dox was removed by changing into fresh medium, monitoring the p53 mRNA levels continued for 0–6 d. The p53 mRNA levels from various days were normalized to initial p53 without Dox addition.

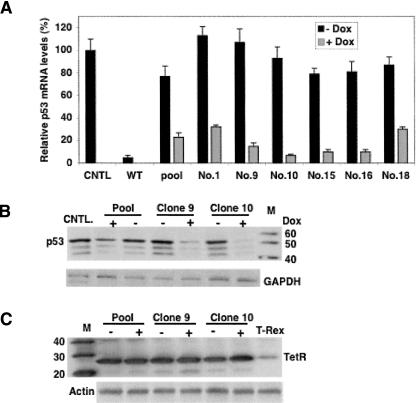

Single cell clones

We isolated and expanded a total of 15 single cell clones from MCF-7 pool cells stably transduced with the inducible p53 siRNA lentiviral vector. Among them, six clones were induced with 1000 ng/mL Dox for 3 d followed by Taqman to analyze their p53 mRNA expression. Data were reported relative to the p53 mRNA level in the negative control, scrambled siRNA-transduced MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6A). Two of the clones analyzed, numbers 9 and 10, exhibit significantly tighter control over siRNA expression—minimal basal transcription and maximum siRNA expression upon induction. We further analyzed these clones by growing them in nonselective medium over 2 wk followed by a 3-d induction with 1000 ng/mL Dox, and found neither exhibited a detectable decrease in p53 protein level in the absence of Dox. In the presence of Dox, both clones displayed a greater reduction in p53 protein expression, with almost no p53 detectable (Fig. 6B). We also tested the potential negative effect of Dox on TetR expression during cell culture that might result in siRNA leakiness rather than working as a switch. Western blot analysis, based on single cell clones 9 and 10, confirmed that the transduced MCF-7 cells expressed substantially more TetR protein than the T-Rex cells as observed in pool cells, and there was no detectable difference in TetR protein level due to addition of Dox in either single cell clone (Fig. 6C). Therefore, Dox has no detectable effect on TetR expression in transduced cells, and the remarkable sensitivity of this system to Dox is due to its switch role.

FIGURE 6.

Single cell clones. (A) Taqman analysis of the p53 mRNA levels in six single cell clones from transduced MCF-7 pool cells that were cultured in the presence and absence of 1000 ng/mL Dox for 3 d. The data were reported relative to the p53 mRNA level in scrambled siRNA-transduced MCF-7 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of the p53 protein in single cell clones 9 and 10, which exhibited less siRNA leakiness under noninduced conditions and significant induction under induced conditions based on Taqman. (C) Western blot analysis of the Dox effect on TetR expression in single cell clones 9 and 10 to confirm that Dox has no effect on TetR expression.

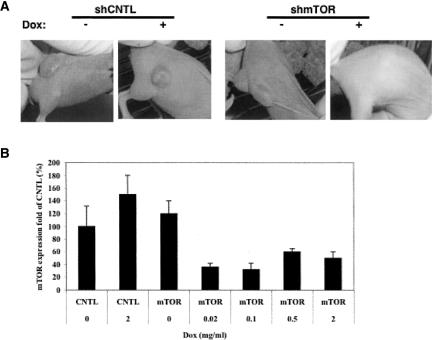

Inducible siRNA expression in xenograft animal models

The single-step requirement for generating double-stable cell lines using this all-in-one lentiviral vector, coupled with its prompt response to a very low dose of Dox, makes it a useful system for studying loss-of-function phenotypes in mammalian cells as well as animal models. For proof of concept we evaluated this inducible system for utility based on a well-known cancer target, mTOR, in a xenograft tumor model, including the early-staged tumor response and the advanced-staged tumor response. For early-staged tumor experiments (Ke et al. 2006), PC3-MC6-luc cells stably transduced with pSD400-mTorsiRNA were implanted into 36 nude mice subcutaneously, 5 × 106 cells per mouse, and then dosing was carried out starting after implantation. Twenty mice carrying the pSD400-CNTL vector served as a control. Our experiment indicated that drinking Dox water caused pSD400-mTorsiRNA xenograft mice 100% tumor repression with 45% becoming tumor-free; drinking regular water showed no significant effect (Fig. 7A). For the pSD400-CNTL control mice, no significant repression phenotype was observed in drinking either regular water or Dox water.

FIGURE 7.

Conditional cancer target mTor silencing and tumor repression by the all-in-one inducible siRNA system in xenograft mice models. (A) Response of early-staged tumors to Dox induction. Eighteen and 22 nude mice were separately implanted with pSD400-CNTL- or pSD400-mTor-transduced PC3-MC6-Luc cells, 52×2106 cells per each mouse, and then 2.0 mg/mL Dox-containing water was given to half of the different xenograft mice, with the remaining given regular water to drink for 1 mo. No significant tumor repression phenotype was observed for mice with the control siRNA system in either the presence or absence of Dox and for mice with mTOR siRNA but drinking regular water, while 100% tumor repression was seen for mTOR siRNA-containing mice that drank Dox water, with 45% become tumor free. (B) Taqman analysis of the mTOR mRNA level in xenograft tumors. Twenty mice with later-staged tumors were divided into five groups with four in each group and were dosed with Dox at 0, 0.02, 0.1, 0.5, and 2 mg/mL in drinking water. Tumor samples were taken out 3 d later for Taqman analysis as previously described (Ke et al. 2006). The expression levels of mTOR mRNA in various xenograft tumors were normalized against that in noninduced control xenograft tumors.

For later-staged tumor experiments, dosing started on day 16 post-implantation when the tumors in xenograft mice grew to an average volume of 100–200 mm3. Compared with the pSD400-CNTL control mice and the pSD400-mTORsiRNA mice that drank regular water, the tumors in pSD400-mTOR xenograft mice showed a significant response to Dox, with almost 100% stopping growth. In further profiling the tumor response to Dox, 20 mice with later-staged tumors were divided into five groups with four in each group and dosed with Dox at 0, 0.02, 0.1, 0.5, and 2 mg/mL in drinking water. Tumor samples were taken out 3 d later for Taqman analysis. As shown in Figure 7B, all four concentrations of Dox gave very good down-regulation of mTOR mRNA. However, there was no clear Dox dose dependence of mTOR reduction, which might be due to Dox itself—stimulating tumor to express more mTOR and thus balancing the Dox-induced, siRNA-mediated mTOR reduction. About a 50% increase of mTOR mRNA by Dox was observed in pSD400-CNTL control xenograft mice (Fig. 7B). These results provided a direct validation of mTOR as a cancer therapeutic target in xenograft mice, a widely accepted animal model for predicting the efficacy of treatment in humans.

DISCUSSION

A major concern regarding the TetR-dependent inducible system is the siRNA leakiness, which is determined by the affinity strength of TetR/TetO within the inducible promoter. However, the limited amount of intracellular TetR is not able to completely occupy the inducible promoter, which usually results in significant suppression of the target gene. The most ideal method to reduce siRNA leakiness is to express a high level of TetR in host cells so that the inducible promoter can be 100% occupied. But this is extremely difficult to attain, and so far no successful example has ever been reported. Instead, most inducible systems designed so far adopt multiple TetOs into the U6 promoter to recruit TetR more efficiently for blocking polymerase binding.

To develop a TetR overexpression inducible system, we took advantage of the bicistronic IRES construct that encoded the puromycin resistance protein and TetR protein via a partially disabled IRES. This IRES reduced the translation rate of the downstream Puro but had less effect on TetR translation in host cells. When the cell culture medium was supplied with a high concentration of puromycin for stable cell selection, only cells with more copies of the TetR-IRES-Puro mRNA for expression of sufficient Puro-resistant protein would preferentially survive, which made a further higher expression level of TetR. The TetR mRNA level in stably transduced cells was ∼15-fold higher than that in T-Rex cells, and much higher expression was observed on the protein level (Figs. 2, 6C). The extremely high level of TetR in stable cells ensures almost 100% occupancy of the regulatory sites within the inducible promoter with minimal basal transcription (Figs. 3, 6B). Furthermore, the regulation of the inducible promoter relies solely on TetR via simple steric hindrance rather than a fusion protein via a more complicated mechanism (Czauderna et al. 2003; Amar et al. 2006; Szulc et al. 2006). So far, no unwanted effect due to TetR overexpression has been observed on cell morphology, cell growth, and gene expression.

In addition, such a high level of TetR expression in stable transduced cells makes it possible to engineer the Tet-responsive promoter with just a single TetO, minimizing the existing impairment on wild-type promoter transcription due to incorporation of multiple TetO sequences. It was estimated that ∼80% of transcription activity remained when a single TetO was introduced into the U6 promoter (Ohkawa and Taira 2000; Ke et al. 2006). Therefore, the strong reduction of siRNA basal transcription by high TetR expression and the marginal disruption of the U6 promoter by the single TetO together produced a maximum regulatory window.

Our all-in-one inducible system, which combined the Tet-responsive U6 promoter, the TetR gene, and a puromycin selection marker in a single lentivector, has the further advantage of converting the double-stable selection processes into just a single-step selection, overcoming the extremely time-consuming issue in the generation of stable cell lines. So far, most reported inducible systems rely on two sequential introductions of the TetR-containing plasmid and a Tet-responsive pol III promoter-harboring plasmid into target cells wherein TetR is required to be constitutively expressed at a tight level. The constitutive expression of TetR and conditional expression of siRNA in stable cells are not only promoter dependent but also integration site dependent. That means large-scale cloning after each transduction is required, usually taking a couple of months, for the final selection of a multiply stable cell line harboring the desired properties. Our all-in-one inducible system can significantly shorten this process into weeks.

Since high doses of Dox usually generate an undesired side effect on cell growth, we want to determine the minimal Dox concentration required to induce siRNA expression. Our data based on p53 siRNA conditional expression indicated that siRNA induction remains remarkably sensitive to Dox, with EC50 ∼5 ng/mL, and even as little as 1 ng/mL Dox induced sufficient siRNA expression to reduce p53 mRNA expression (Fig. 5). These data plus the reversal time courses of siRNA expression and repression upon Dox induction and withdrawal (Fig. 5B) revealed that despite high levels of TetR expression in transduced cells, the siRNA expression in this system is clearly inducible and reversible.

A key challenge and essential step in drug development is identification of the right drug targets. One effective way to validate a potential target is to introduce a siRNA that mimics an antagonist into cancer cells to evaluate its effect on the tumor cell transformation phenotype (Ke et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2006). However, inhibition of cancer therapeutic target expression often leads to cell death, preventing the production of stably silenced cells to be used in xenograft models, which are always more reliable to predict the therapeutic value of the target. Although it is possible to obtain tightly inducible knockdown of a potential target in stable tumor cells using the sequential transduction of a TetR vector and inducible siRNA vector from large-scale clone screens (Lin et al. 2004), using the all-in-one lentivector could markedly shorten the time requirement in generating such a stable cell line and improve the success rate. This is particularly important for making xenograft animals due to the long time requirement and associated high cost.

Here, as a proof of principle, we have demonstrated the powerful utility of this all-in-one inducible system for efficacy evaluation of the cancer target mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase that functions downstream of Akt to regulate cell growth and proliferation, in xenograft tumor models and provided a direct in vivo efficacy validation of this gene as an effective therapeutic target for pTEN-deficient cancer treatment (Bjornsti and Houghton 2004). Our experiments clearly indicated that siRNA-mediated mTOR silencing upon Dox induction caused 100% tumor regression for the early-staged PC3 tumors in xenografic mice, with 45% becoming tumor-free (Fig. 7A). In the advanced-staged tumor model, significant Dox-dependent mTOR gene silencing and tumor growth repression were also observed (Fig. 7B), strongly supporting the conclusion that mTOR is a cancer therapeutic target. This observation confirmed the utility of the all-in-one system for cancer therapeutic target evaluation in xenograft animals and raises most exciting perspectives for the development of conditional transgenic and knockdown models in a wide variety of mammals. Clearly, this all-in-one inducible siRNA system with a high level of TetR expression provides a unique and more efficient tool in comparison to the existing systems for conditional gene knockdown, and displays a high degree of robustness and versatility for regulation of siRNA expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of siRNA and TetR expression vectors

The inducible siRNA expression cassette variants with one or more copies of TetO around DSE, PSE, and TATA in the mouse U6 promoter (Fig. 1A) were generated by PCR and PCR assembling (Chen et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2004). The TetO sequence and the sense sequences of p53-siRNA, mTOR-siRNA, and scrambled siRNA were 5′-CTCTATCATTGATAGAGT-3′, 5′-GACTCCAGTGGTAATCTAC-3′, 5′-CTCTTCTTTACCTTCTTTA-3′, and 5′-GGCGCGCTTTGTAGGATTCGC-3′. The lentiviral vector for constitutive siRNA expression was pSD31, which contained a BamHI site downstream of the 5′-LTR for cloning regular siRNA expression cassettes (Fig. 1B). The inducible lentivector, pSD400, was derived from pSD31 by replacement of the SV40-PuroR expression cassette with CMV-TetR-IRES-Puro and then introducing a new BamHI at its 3′ -LTR for cloning-inducible siRNA expression cassettes (Fig. 1B). The CMV-TetR-IRES-Puro cassette was constructed as follows: The TetR gene was amplified from plasmid pcDNA6/TR (Invitrogen) by PCR using primers 5′-GCGGCCGCTAGGGCCTCTGAGCTATTCC-3′ and 5′-GAATTCTCTGCTTTAATAGGATCTGAACTCCCGGGAACCGCTGTACGCGGA-3′. The PCR product was then cloned at the NotI–EcoRI sites of the pQCXIP plasmid (Clontech), digested by BglII/EcoRV, and ligated into the pHIV-7 vector (kindly provided by Professor John Rossi) at the BamHI/SmaI sites. This new pHIV-7 plasmid was inserted at the PflMI/KpnI sites with a modified 3′- LTR fragment wherein the BglII site was replaced by BamHI, generating the inducible vector pSD400. Replacement of the BglII site within the 3′ -LTR with BamHI was carried out through mutagenesis using the primers 5′-CCCAAAGAAGACAGGATCCGCTTTTTGCCTGTACT-3′ and 5′-AGTACAGGCAAAAAGCGGATCCTGTCTTCTTTGGG-3′ and pHIV-7 as the template.

Cell culture, lentivector package, and stable transduction

Mammalian cells used in this study include human breast tumor MCF-7 cells for evaluation of siRNA function, embryonic kidney 293FT cells for lentivector packaging, and PC3-MC6-luc cells for xenograft animal studies (Xenogen). These cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium with high glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS), 1 mM sodium pyrumide, and 1 mM nonessential amid acids (Invitrogen). For inducible siRNA expression, the 10% FBS was changed to 10% heat-inactivated tetracycline-free FBS (Clontech). All cell lines were split every 3–4 d. Lentiviral vector production was performed according to Invitrogen's standard protocols. Briefly, subconfluent 293FT cells in a T225 flask were cotransfected with 20 μg of siRNA lenti-plasmid, 15 μg of pCMV-DR8.91, and 5 μg of pMD2G-VSVG using the transfection reagent Trans-LT1 (Mirus). After a medium change 6 h later, the lentiviruses were harvested at 72 h and filtered with a 0.45 μm filter. Experiments for lentivector stable transduction were carried out as follows: 1E6 of MCF-7 cells were seeded in a T25 flask and transduced at day 2 in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene with ∼1E6 of lentiviral vector. Selection was performed from day 3 by 450 ng/mL puromycin until parental cells from a parallel experiment completely died. Experiments for Dox induction were performed using tetracycline-free medium supplemented with the desired amount of Dox. Prior to Dox induction, cells were grown for 1 wk in tetracycline-free medium.

Western blot analysis

Cultured cells were washed once with PBS buffer and lysed in lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM EDTA) for 5 min and passed through a 27-gauge needle. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000g for 1 min, and protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 4% – 20% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk or 3% bovine serum albumin in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. Primary and secondary antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by detection with an enhanced chemiluminescence technique (Amersham Biosciences). Western quantitations were performed as follows: Western blots were scanned by a densitometer to get the density of each band. Then, the density ratio of each band to its internal control band (either actin or GAPDH) was relative to the ratio from the negative control siRNA, which is normalized as 100%.

Taqman analysis

Quantitative real-time RT–PCR (Taqman assay) was carried out to determine the endogenous p53 and exogenous TetR mRNA expression levels in stably transduced MCF-7 cells. Dual-labeled fluorogenic probes and primers were synthesized at Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., and a one-step real-time RT–PCR was carried out using an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) as described previously (Hu et al. 2004). Real-time PCR data were collected using the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system. Relative quantification of the p53 mRNAs was achieved according to the principle of the standard-based quantitative PCR method (Hu et al. 2004). Briefly, an RNA stock expressing the appropriate target was used as a calibrator to generate a standard curve. The target quantity of test samples was derived from the standard curve through the comparison of the values of fluorescent signal intensity. The amplification of a “housekeeping” gene transcript, 18S rRNA, was carried out to standardize the amount of RNA added to a reaction. The amount of a target transcript was divided by the amount of 18S rRNA to obtain the normalized target quantity. The amount of target transcripts, p53 and TetR, was divided by the amount of 18S rRNA to obtain the normalized target quantity as described previously (Hu et al. 2004). The variation was obtained from analysis of three parallel groups of RNA with error bars ∼15%.

Xenograft model

5E6 cells of PC3-MC6-luc cells containing either pSD400-CNTL or pSD400-mTOR were injected into nude mice by subcutaneous injection. For early-staged tumor experiments, PC3-MC6-luc xenografts were dosed with Dox on the day of injection. For advanced-staged tumor experiments, the tumors in xenograft mice were allowed to grow to an average tumor volume of 100–200 mm3. The animals were then divided into a couple of groups with four in each group. Different groups of animals were then treated with different concentrations of Dox added to drinking water. Tumor samples were taken out 3 d later, and RNA preparation and Taqman analysis were conducted as described (Ke et al. 2006). The expression levels of mTOR mRNA in xenograft tumors were normalized against control mice that did not drink Dox.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.520707.

REFERENCES

- Amar, L., Desclaux, M., Faucon-Biguet, N., Mallet, J., Vogel, R. Control of small inhibitory RNA levels and RNA interference by doxycycline induced activation of a minimal RNA polymerase III promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angela, M.D., Kunkel, G.R. Multiple, dispersed human U6 small nuclear RNA genes with varied transcriptional efficiencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2344–2352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, G.M., Medzhitov, R. Retroviral delivery of small interfering RNA into primary cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:14943–14945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242594499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsti, M.A., Houghton, P.J. The TOR pathway: A target for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp, T.R., Bernards, R., Agami, R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calegari, F., Haubensak, W., Yang, D., Huttner, W.B., Buchholz, F. Tissue-specific RNA interference in postimplantation mouse embryos with endoribonuclease-prepared short interfering RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:14236–14240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192559699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Stamatoyannopoulos, G., Song, C.Z. Down-regulation of CXCR4 by inducible small interfering RNA inhibits breast cancer cell invasion in vitro. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4801–4804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czauderna, F., Santel, A., Hinz, M., Fechtner, M., Durieux, B., Fisch, G., Leenders, F., Arnold, W., Giese, K., Klippel, A., et al. Inducible shRNA expression for application in a prostate cancer mouse model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003 doi: 10.1093/nar/gng127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroe, E., Silver, P.A. Retrovirus-delivered siRNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2002;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donze, O., Picard, D. RNA interference in mammalian cells using siRNAs synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e46. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen, M., Bujard, H. Studying gene function in eukaryotes by conditional gene inactivation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2002;36:153–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041002.120114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, G.J., Rossi, J.J. Unlocking the potential of the human genome with RNA interference. Nature. 2004;431:371–378. doi: 10.1038/nature02870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X., Hipolito, S., Lynn, R., Abraham, V., Ramos, S., Wong-Staal, F. Relative gene-silencing efficiencies of small interfering RNAs targeting sense and antisense transcripts from the same genetic locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4609–4617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke, N., Zhou, D., Chatterton, J.E., Liu, G., Chionis, J., Zhang, J., Tsugawa, L., Lynn, R., Yu, D., Meyhack, D., et al. A new inducible RNAi xenograft model for assessing the staged tumor response to mTOR silencing. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:2726–2734. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.S., Dohjima, T., Bauer, G., Li, H., Li, M.J., Ehsani, A., Salvaterra, P., Rossi, J. Expression of small interfering RNAs targeted against HIV-1 rev transcripts in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:500–505. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X., Yang, J., Chen, J., Gunasekera, A., Fesik, S.W., Shen, Y. Development of a tightly regulated U6 promoter for shRNA expression. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukura, S., Jones, P.A., Takai, D. Establishment of conditional vectors for hairpin siRNA knockdowns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister, G., Tuschl, T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature. 2004;431:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C.C., Conte D., Jr Revealing the world of RNA interference. Nature. 2004;431:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature02872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi, M., Taira, K. U6 promoter-driven siRNAs with four uridine 3′ overhangs efficiently suppress targeted gene expression in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, J., Sabatini, D.M. Building mammalian signaling pathways with RNAi screens. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa, J., Taira, K. Control of the functional activity of an antisense RNA by a tetracycline-responsive derivative of the human U6 snRNA promoter. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000;11:577–585. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paule, M.R., White, R.J. Survey and summary: Transcription by RNA polymerases I and III. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1283–1298. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.F., An, D.S., Chen, I.S., Baltimore, D. Inhibiting HIV-1 infection in human T cells by lentiviral-mediated delivery of small interfering RNA against CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:183–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees, S., Coote, J., Stables, J., Goodson, S., Harris, S., Lee, M.G. Bicistronic vector for the creation of stable mammalian cell lines that predisposes all antibiotic-resistant cells to express recombinant protein. Biotechniques. 1996;20:102–110. doi: 10.2144/96201st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui, G., Soohoo, C., Affar, el B., Gay, F., Shi, Y., Forrester, W.C., Shi, Y. A DNA vector-based RNAi technology to suppress gene expression in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:5515–5520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082117599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc, J., Wiznerowicz, M., Sauvain, M.O., Trono, D., Aebischer, P. A versatile tool for conditional gene expression and knockdown. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:109–116. doi: 10.1038/nmeth846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiscornia, G., Singer, O., Ikawa, M., Verma, I.M. A general method for gene knockdown in mice by using lentiviral vectors expressing small interfering RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:1844–1848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437912100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N., Cairns, M.J., Dawes, I.W., Arndt, G.M. Expressing functional siRNAs in mammalian cells using convergent transcription. BMC Biotechnol. 2003 doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering, M., Oving, I., Muncan, V., Pon Fong, M.T., Brantjes, H., van Leenen, D., Holstege, F.C., Brummelkamp, T.R., Agami, R., Clevers, H. Specific inhibition of gene expression using a stably integrated, inducible small-interfering-RNA vector. Embo Rep. 2003;4:609–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiznerowicz, M., Trono, D. Conditional suppression of cellular genes: Lentivirus vector-mediated drug-inducible RNA interference. J. Virol. 2003;77:8957–8961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8957-8961.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H., Mao, Q., Paulson, H.L., Davidson, B.L. siRNA-mediated gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1006–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., Goga, A., Bishop, J.M. RNA interference (RNAi) with RNase III-prepared siRNAs. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;252:471–482. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-746-7:471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore, P.D., Haley, B. Ribo-gnome: The big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L., Liu, J., Batalov, S., Zhou, D., Orth, A., Ding, S., Schultz, P.G. An approach to genomewide screens of expressed small interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:135–140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136685100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D., He, C., Wang, C., Zhang, J., Wong-Staal, F. RNA interference and potential applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:901–911. doi: 10.2174/156802606777303630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]