Abstract

The study reported here explored the associations of body mass index (BMI), socio-economic status (SES), and beverage consumption in a very low income population. A house-to-house survey was conducted in 2003 of 12,873 Mexican adults. The sample was designed to be representative of the poorest communities in seven of Mexico’s thirty-one states.

Greater educational attainment was significantly associated with higher BMI and a greater prevalence of overweight (25≤BMI<30) and obesity (30≤BMI) in men and women. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was over 70% in women over the median age of 35.4 years old with at least some primary education compared with a prevalence of 45% in women below the median age with no education. BMI was positively correlated with five of the six SES variables in both sexes: education, occupation, quality of housing conditions, household assets, and subjective social status. BMI and household income were significantly correlated in women but not in men. In the model including all SES variables, education, occupation, housing conditions and household assets all contributed independently and significantly to BMI, and household income and subjective social status did not.

Increased consumption of alcoholic and carbonated sugar beverages was associated with higher SES and higher BMI in men and women. Thus, in spite of the narrow range of socio-economic variability in this population, the increased consumption of high calorie beverages may explain the positive relationship between SES and BMI.

The positive associations between SES and BMI in this low-income, rural population are likely to be related to the changing patterns of food availability, food composition, consumption patterns and cultural factors. Contextually sensitive population-level interventions are critically needed to address obesity and overweight in poor populations, particularly in older women.

Keywords: nutrition transition, socio-economic status (SES), social status, poverty, Mexico, body mass index (BMI)

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight or obesity in Mexico is over 60% in women and 50% in men, and these estimations of prevalence are as high in adults from poor rural areas as they are in a nationally representative sample of adults (Fernald, Gutierrez, Neufeld, Mietus-Snyder, Olaiz, Bertozzi et al., 2004). Obesity is a serious, chronic condition that contributes to numerous preventable diseases, including hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Hill, Catenacci, & Wyatt, 2006), which are already present in a large number of Mexicans (Aguilar-Salinas, Velazquez Monroy, Gomez-Perez, Gonzalez Chavez, Esqueda, Molina Cuevas et al., 2003). It has been estimated that 60% of the burden of chronic diseases will occur in developing countries by 2020 (WHO, 2002). A critical remaining concern is whether there is variation within middle-income countries such as Mexico that could leave certain segments of the population more vulnerable to chronic diseases than others.

In the developed world there is a consistently inverse relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and obesity or overweight for women, and no relationship in men or children (Sobal & Stunkard, 1989). In contrast, there is a positive relationship between SES and obesity in both sexes in the developing world. However, increasing evidence from between-country analyses reveals that the association of obesity and per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is not a constant function (Monteiro, Moura, Conde, & Popkin, 2004). A meta-analysis of 30 countries showed a positive association between SES and obesity, but only in lower income developing countries – those with a GDP per capita <2500USD (Monteiro, Conde, Lu, & Popkin, 2004). National data from poorer countries in Latin America, such as Guatemala and Honduras, for example, show higher levels of SES associated with a greater prevalence of obesity; however, in the richer countries, like Mexico, there is a clear negative association between SES and obesity (Barquera, Rivera, Espinosa-Montero, Safdie, Campirano, & Monterrubio, 2003).

A remaining question is whether these between-country comparisons can be extended to within-country analyses. In other words, within a sub-group of the population, would the association between SES and BMI reflect a country’s mean GDP per capita or would it reflect a different relationship depending on the mean GDP of the sub-population being investigated? Only a few studies have looked at these patterns, leaving a large research gap. In one study, an examination of SES and obesity in women in India, there was a consistently positive association between SES and the prevalence of overweight and obesity across states with varying per capita net domestic product, except for women in the lowest SES quintile (Subramanian & Smith, 2006).

The first goal of the analysis reported here was to examine the associations between BMI and SES in a rural, poor population within Mexico, a middle-income country. With an average GDP per capita of $9600, Mexico is positioned well above the $2500 threshold described above. For this reason, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that increasing SES would be associated with decreasing BMI. However, given that Mexico is currently undergoing nutritional transition, it is also possible that the association between SES and BMI in a low-income population (GDP/capita <1000USD) could be positive, matching the pattern seen in countries such as India with a lower GDP per capita.

The second goal of the analysis was to assess the contribution of behavioral characteristics to BMI and to explore the associations between SES and these behaviors. In other words, if there are differences in body mass index by SES, is it possible that behavioral factors could mediate these relationships? The analyses focused on the consumption of sweetened, carbonated beverages (DiMeglio & Mattes, 2000; Malik, Schulze, & Hu, 2006; Schulze, Manson, Ludwig, Colditz, Stampfer, Willett et al., 2004) and alcoholic beverages (Wannamethee, Field, Colditz, & Rimm, 2004; Wannamethee & Shaper, 2003), which have each been shown to be independently linked with obesity.

Research design and methods

Data source

The survey reported here was conducted in 2003 in 12,873 adults from 364 communities as part of a National Social Welfare Survey, which was designed to be representative of the poorest (income <20th percentile), rural (defined as towns with <2,500 inhabitants), communities in seven (Guerrero, Hidalgo, Michoacán, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz) of Mexico’s thirty-one states (Behrman & Todd, 1999a). These regions had a mean daily per capita income of ≤$2US. Households were selected in two stages: first by identifying low-income communities and then by choosing low-income households within those communities (Behrman & Todd, 1999b, 1999a). Households were surveyed from September to December between 0800 and 1800 on all days of the week except Sundays. One or sometimes two adult members of each household were interviewed and in the majority of cases the person interviewed was the adult female; if both the adult male and female were at home, they were both interviewed. The interview teams were instructed to return to each home a minimum of three times to conduct the survey.

Body mass index

Height and weight were measured by trained and standardized personnel using standard techniques (Habicht, 1974; Lohman, Roche, & Martorell, 1989). Body mass index (BMI), a marker for obesity that correlates well with body fat, was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (Roche, Siervogel, Chumlea, & Webb, 1981). Overweight was defined as 25≤BMI<30 and obesity as 30≤BMI (WHO, 1995).

Socio-economic status

Education

Educational attainment of the survey respondent was assessed; this measure of SES has been widely used and is related to health outcomes (Singh-Manoux, Clarke, & Marmot, 2002; Winkleby, Jatulis, Frank, & Fortmann, 1992) including obesity (Zhang & Wang, 2004a). Educational attainment was included in the model as two dummy variables (completion of some elementary school; completion of some secondary school), with reference to the baseline group (no education).

Occupation

Current occupation, another common measure of SES (MacIntyre, McKay, Der, & Hiscock, 2003; Marmot, Kogevinas, & Elston, 1987), was obtained and entered into the models as three dummy variables for women and two for men. The categories were 1) housewife (used as baseline for women), 2) day laborer or domestic servant (used as baseline for men), 3) working in a family or other small business, and 4) owner of a small business.

Household income

Household income, which has been shown to correspond with general measures of health (MacIntyre, McKay, Der et al., 2003) and obesity (Zhang & Wang, 2004b), was calculated using self-reported measures of income in the past year contributed by all working members of the family from primary and secondary occupations. Income was logarhythmically transformed to adjust for positive skew.

Housing and assets

Two additional proxy measures of SES were generated: one summary measure of household assets (twelve variables) and the other of housing quality (six variables). The housing and asset measurements were obtained in a baseline survey that occurred in 1997 in a sub-set (about two-thirds) of the same households. Assets included: car, van, refrigerator, blender, television, gas heater, boiler, radio, stereo, video cassette recorder, washing machine and fan; housing characteristics included quality of roof, wall and floor, number of rooms, presence of indoor bathroom, and presence of indoor electricity. These variables have been shown to provide good estimations of the economic concept of consumption, the gold standard measure of SES (McGee & Brock, 2001; Moser, 1998). Principal components analysis was used to summarize the asset variables into one measure and the housing variables into another measure (Falkingham & Namazie, 2002; Montgomery, Gragnolati, Burke, & Paredes, 2000). In both cases, the first principal component was retained (Filmer & Pritchett, 2001).

Subjective social status

Subjective social status was assessed using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, which asks participants to place themselves on a ladder in reference to a population. The instrument has two parts, one linked to traditional SES indicators (income and education) and one linked to a more immediate, local environment (placement in local community). Specifically, a person’s assessment of where they fit on the ladder representing their community or country indicates where that person imagines that they fall relative to other members of their reference group. These ladders have been used in several diverse studies with adults, and have been shown to be extremely powerful determinants of health-related outcomes, even when traditional measures of SES are included (Goodman, Adler, Kawachi, Frazier, Huang, & Colditz, 2001; Hu, Adler, Goldman, Weinstein, & Seeman, 2005). The ladders were incorporated in this study to assess the contribution of self-reported social status over and above objective measures of SES. In addition to providing a subjective comparison to the objective measures being included in the analysis, the ladders also add an element of relative status to the other measures. A score consisting of the sum of the values on both ladders was calculated.

Beverage consumption

Information was obtained about beverage consumption (sweetened carbonated soda and alcoholic beverages). Two variables were generated: soda consumption (“0 or 1 can of soda in the last week” was coded as a 0 and anything higher as 1) and alcohol consumption (1 was “drinking occasionally”, 0 was not).

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 9.2 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). Analyses were adjusted to account for clustering at the household level. For BMI, non-plausible values and outliers more than 3 S.D. away from the mean were identified and excluded (n=28 values removed). Participants were excluded if they were younger than 18 years old (n=26), older than 65 (n=484), or missing a value for age (n=202). The final sample for analysis was 12,094, which was reduced to 11,528 for those with complete data from most SES variables. A sub-sample of 9,431 had data available for housing and assets from a baseline survey in 1997. There were no systematic differences in BMI or prevalence of overweight or obesity between participants with missing data and those with complete data. Descriptive statistics were generated by sex; between-sex comparisons were made with one-way ANOVAs for continuous variables, and analyses of proportions for non-continuous variables (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

In order to address the first goal of the paper and examine the relationship between BMI and various measures of SES, linear regressions were performed with BMI as the dependent variable and the following independent variables: 1) education; 2) occupation; 3) household income; 4) housing conditions and assets; and 5) subjective social status. A final linear regression included all measures of SES to explore which of the various measures were most strongly associated with BMI. After the regressions were completed, linear combinations of estimators were computed to assess the significance of the various contrasts within the indicator variables used for education and occupation. To address the second goal of the paper, which was to study the contribution of additional behavioral characteristics to BMI, analyses were completed using behaviors as independent variables and BMI as the dependent variable, with and without SES. In order to test the hypothesis that having higher SES allows people to purchase and consume more carbonated beverages and alcohol, two models were generated with soda and alcohol consumption as the outcome measures and all measures of SES included simultaneously as the independent variables. All analyses were conducted separately by sex, and age was centered and included in all models.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Committee at the National Institute of Public Heath in Mexico, and the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California at Berkeley. Participants were invited to participate after receiving a detailed explanation of the survey procedures and they were then asked to sign an informed consent declaration.

Results

The mean BMI was over 25 in both sexes, and significantly greater in women than men (Table 1). The majority of men and women were classified as overweight or obese with a greater proportion of women categorized as obese (22.5%) than men (13.4%). The mean age for men was older than for women because younger men were often laboring away from home during the days and not available for interview. The SES data reflect the very high levels of poverty of the households targeted for recruitment into this study, with the large majority of participants having completed no schooling or only some primary school. Most women were not working outside the home and most of the men were.

TABLE 1.

Selected socio-demographic, health and behavioral characteristics of study participants.a

| Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Diffb | |

| Weight status | |||||||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 2557 | 25.7 | 4.0 | 9042 | 26.7 | 4.8 | *** |

| Weight classification (%) | |||||||

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 38 | 1.5% | 116 | 1.3% | NS | ||

| Normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25 ) | 1188 | 46.1% | 3548 | 39.1% | *** | ||

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30) | 1006 | 39.0% | 3368 | 37.1% | NS | ||

| Obese (BMI≥30) | 344 | 13.4% | 2039 | 22.5% | *** | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (yr) | 2576 | 45.3 | 9.7 | 9071 | 35.4 | 10.5 | *** |

| Socio-economic status | |||||||

| Educational achievement | |||||||

| 0: No schooling at all (%) | 362 | 14.4% | 1531 | 16.9% | ** | ||

| 1: Primary school (%) | 1838 | 71.4% | 6109 | 67.3% | *** | ||

| 2: Secondary school (%) | 308 | 12.0% | 1295 | 14.3% | ** | ||

| Occupation | |||||||

| 0: Housewife/not working (%) | 152 | 5.9% | 7150 | 78.8% | *** | ||

| 1: Day laborer or maid (%) | 1186 | 46.0% | 541 | 6.0% | *** | ||

| 2: Work in small business (%) | 964 | 37.4% | 789 | 8.7% | *** | ||

| 3: Own or supervise business (%) | 274 | 10.6% | 591 | 6.5% | *** | ||

| Household income (log transformed) | 2576 | 9.0 | 3.1 | 9071 | 9.3 | 2.9 | *** |

| Housing conditionsc | 2198 | −0.12 | 1.5 | 6950 | 0.03 | 1.5 | *** |

| Household assetsd | 2192 | 0 | 1.9 | 6934 | 0 | 1.9 | NS |

| Subjective social status scalee | 2576 | 6.0 | 3.5 | 9071 | 5.8 | 3.6 | ** |

| Beverage consumption Characteristics | |||||||

| Consumption of carbonated, sugar beverages in the past week (%consuming more than 1) | 2576 | 51.5% | 2818 | 31.1% | *** | ||

| Consumption of alcoholic beverages (% drink alcoholic beverages, even occasionally) | 2576 | 60.1% | 9071 | 12.9% | *** | ||

Adjusted for sampling design, stratification and clustering.

Statistical testing (ANOVA for continuous variables and tests for proportions for percentages, adjusted for sampling design) for differences between men and women.

Housing variable was developed using principal components analysis (PCA) summarizing six housing variables (e.g. roof, walls, floor). The PCA generates values centered at 0 (zero).

Assets variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing twelve asset variables (e.g. television, radio, blender). The PCA generates values centered at 0 (zero).

Developed by the MacArthur Network on SES and Health. Higher score represents higher level of perceived social status.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001

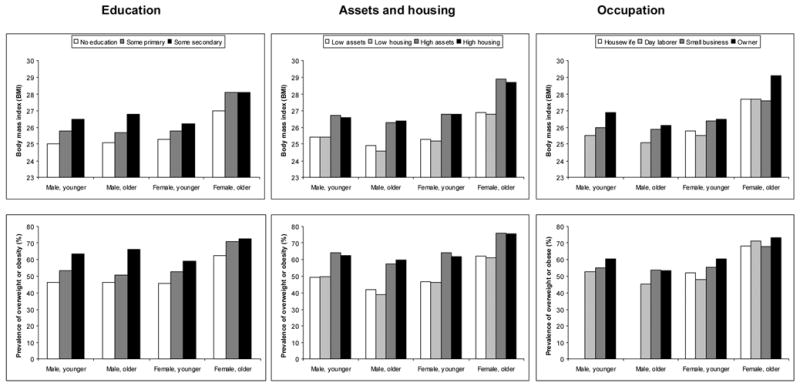

Greater educational attainment was significantly associated with higher BMI and a greater prevalence of overweight and obesity in men and women (Figure 1). The same finding was evident in the relationship between BMI and assets, housing and occupation. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was over 70% in women over the median age of 35.4 years old with at least some primary education compared with a prevalence of 45% in women below the median age with no education. Over 75% of women above than the median age with housing and asset scores above the median could be classified as overweight or obese, in comparison with less than 50% of younger women with lower housing and asset scores.

Figure 1.

Body mass index (BMI) in top row and prevalence of overweight (25≤BMI<30) and obesity (BMI≥30) in bottom row of males and females by educational attainment (three categories), assetsa and housingb (each split at median), and occupationc (four categories). Groups are divided by age at the median (by sex).

a. Assets variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing twelve asset variables (e.g. television, radio, blender). Data were collected in 1997.

b. Housing variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing six housing variables (e.g. roof, walls, floor). Data were collected in 1997

c. Occupation categories are: “Housewife”; “Day laborer”, which includes people working as maids and domestic servants; “Small business”, which includes those employed in a family or other small business; and “Owner”, which includes those working as a patrón or owner of a small business

BMI was positively correlated with five of the six SES variables in both sexes (Table 2, Models 1 to 5): education, occupation, quality of housing conditions, household assets, and subjective social status. BMI and household income were significantly correlated in women and not in men. In the full model (Table 2, Model 6), education, occupation, housing conditions and household assets all contributed independently and significantly to BMI. In comparison to women who had received no education, those who had completed some primary school (B=0.75, p<0.0001) or some secondary school (B=0.68, p<0.05) had significantly higher BMI; there was no difference between completing some primary and some secondary school (B=−0.11, p=NS, data not shown). In the full model for men, there was a non-significant trend of an association between completion of secondary school and having a higher BMI (B=0.62, p=0.08); there was no difference between some primary and some secondary (B=0.27, p=NS, data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Results from multiple linear regression with body mass index (BMI) as the independent variable, and various measures of socio-economic status as independent variables by sex. B(S.E.) presented separately for men (plain text) and women (bold text).a

| Model 1

N=2489 men N=8907 women |

Model 2

N=2421 men N=9042 women |

Model 3

N=2557 men N=9042 women |

Model 4

N=2170 men N=6889 women |

Model 5

N=2557 men N=9042 women |

Model 6

N=2015 men N=6778 women |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), centered | −0.01 (0.01)

0.11 (0.01)*** |

−0.02 (0.01)*

0.10 (0.01)*** |

−0.01 (0.01)

0.10 (0.01)*** |

−0.04 (0.01)***

0.08 (0.01)*** |

−0.01 (0.01)

0.10 (0.00)*** |

−0.03 (0.01)***

0.09 (0.01)*** |

| Educationb | ||||||

| Primary school | 0.64 (0.23)**

1.16 (0.14)*** |

0.35 (0.25)

0.75 (0.16)*** |

||||

| Secondary school | 1.40 (0.32)***

1.57 (0.18)*** |

0.62 (0.36)‡

0.64 (0.22)** |

||||

| Occupationc | ||||||

| Day laborer or maid | ----

−0.15 (0.20) |

------

−0.11 (0.25) |

||||

| Family business | 0.70 (0.17)***

0.26 (0.18) |

0.49 (0.19)**

0.11 (0.20) |

||||

| Own business | 1.21 (0.28)***

1.05 (0.21)*** |

0.76 (0.31)*

0.86 (0.24)*** |

||||

| Household incomed | 0.01 (0.03)

0.03 (0.02)* |

0.01 (0.03)

0.00 (0.02) |

||||

| Housing conditionse | 0.40 (0.07)***

0.27 (0.06)*** |

0.34 (0.07)***

0.47 (0.05)*** |

||||

| Assetsf | 0.49 (0.05)***

0.18 (0.04)*** |

0.28 (0.06)***

0.16 (0.04)*** |

||||

| Subjective social status scaleg | 0.05 (0.02)*

0.06 (0.01)*** |

0.01 (0.01)

0.01 (0.02) |

||||

| Intercept | 25.11

25.95 |

25.44

26.83 |

25.78

26.60 |

26.07

26.94 |

25.53

26.57 |

25.26

26.20 |

| R-squared | 0.0084

0.0561 |

0.0127

0.0491 |

0.0011

0.0464 |

0.0589

0.0799 |

0.0029

0.0480 |

0.0679

0.0860 |

Adjusted for sampling design. Sample sizes vary because housing and assets variables collected in previous survey and only available for sub-sample.

Baseline comparison group is no education.

Models with occupation include all women, only those men who are currently working for men. Baseline comparison group is lowest level of employment (day laborer) for men and not working outside the home for women.

Household income is based on self-report. Values are logarhythmically transformed.

Housing variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing six housing variables (e.g. roof, walls, floor).

Assets variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing twelve asset variables (e.g. television, radio, blender).

Developed by the MacArthur Network on SES and Health. Higher score represents higher level of perceived social status.

P<0.10,

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001

Women in the highest occupational group had significantly higher BMI when compared with those who were not working (B=0.86, p<0.0001), were day laborers or maids (B=0.96, p=0.004, data not shown) or were working in a small business (B=0.75, p=0.011, data not shown). In contrast to men who were working as day laborers, those working in a family business (B=0.49, p=0.009) or as business owners (B=0.76, p=0.014) had higher BMI values; there was no difference in BMI between men in a family business or those who owned the business. Neither household income nor subjective social status was significant in the full model for either sex.

Increased age-adjusted BMI was associated with increased consumption of carbonated, sugar beverages, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages in both sexes, and the findings remained significant with the inclusion of the socio-economic variables (Table 3). Education, housing and asset variables were significant in the final models for women, as was one of the occupation contrasts. Both occupation contrasts, housing and asset variables were significant in men. When comparing the coefficients from Model 6 in Table 2 and the third and fourth columns of Table 3, it is clear that the contributions of the SES variables to the models were attenuated somewhat with the inclusion of the soda and alcohol consumption measures, suggesting a mediational pathway, although the effects sizes are small.

TABLE 3.

Results from multiple linear regression with body mass index (BMI) as the independent variable, and behavioral characteristics as independent variables.a B and S.E. are presented.

| Simple model | Model including SES variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men N=2557 | Women N=9041 | Men N=2015 | Women N=6777 | |

| Age (years) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.00)*** | −0.03 (0.01)*** | 0.09 (0.01)*** |

| Consumption of sodab | 1.00 (0.16)*** | 0.52 (0.11)*** | 0.76 (0.18)*** | 0.30 (0.12)* |

| Consumption of alcoholc | −0.11 (0.16) | 0.85 (0.15)*** | −0.11 (0.18) | 0.58 (0.17)*** |

| Educationd | ||||

| Primary school | 0.33 (0.25) | 0.72 (0.16)*** | ||

| Secondary school | 0.58 (0.36) | 0.56 (0.22)* | ||

| Occupatione | ||||

| Day laborer or maid | ----- | −0.14 (0.25) | ||

| Small business | 0.48 (0.19)* | 0.07 (0.20) | ||

| Owner | 0.69 (0.31)* | 0.83 (0.23)*** | ||

| Household incomef | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.02) | ||

| Housing conditionsg | 0.31 (0.07)*** | 0.46 (0.05)*** | ||

| Assetsh | 0.27 (0.06)*** | 0.15 (0.04)*** | ||

| Subjective social status scalei | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Intercept | 25.36 | 26.64 | 24.98 | 26.11 |

| R-squared | 0.0164 | 0.0525 | 0.0765 | 0.0743 |

Adjusted for sampling design.

Soda consumption: 1 = consumption of more than one carbonated, sugar beverage in the past week

Alcohol consumption: 1=drink alcoholic beverages, even occasionally

Baseline comparison group is no education.

Models with occupation include all women and men who are currently working. Baseline comparison group is lowest level of employment (day laborer) for men and not working outside the home for women.

Household income is based on self-report. Values are logarhythmically transformed.

Housing variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing six housing variables (e.g. roof, walls, floor).

Assets variable was developed using principal components analysis summarizing twelve asset variables (e.g. television, radio, blender).

Developed by the MacArthur Network on SES and Health. Higher score represents higher level of perceived social status.

P<0.10,

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.00

SES was positively associated with the consumption of carbonated beverages and alcohol (Table 4). Soda consumption was significantly positively associated with completion of at least some secondary school in women when compared with those who had received no education (OR=1.38, p<0.05) or only primary education (OR=1.30, p=0.001, data not shown). In men, there was no association between educational attainment and soda consumption. Women working outside the home in any capacity, when compared with housewives, were more likely to have consumed soda in the past week, even while controlling for all other SES variables. Women of the highest occupational grade were more likely to have consumed soda than housewives (OR=1.60, p<0.0001), domestic servants (OR=1.53, p=0.004, data not shown), or women in small businesses (OR=1.35, p=0.02, data not shown). Men at the highest occupational grade were more likely to have consumed soda in the past week than day laborers (OR=1.37, p=0.043) or those working in a family business (OR=1.40, p=0.032, data not shown). Housing, assets and subjective social status were significantly positively associated with soda consumption in both sexes.

TABLE 4.

Logistic regressions with soda consumption and alcohol consumption as independent variables and socio-economic status as independent variables by gender.a Odds ratios and confidence intervals presented for N=2029 men and N=6797 women.

| Soda consumptionb | Alcohol consumptionc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Educational attainmentd | ||||

| Primary | 1.11 (0.87–1.44) | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 1.07 (0.82–1.39) | 1.50*** (1.20–1.88) |

| Secondary | 1.32 (0.90–1.95) | 1.38** (1.12–1.70) | 1.39‡ (0.93–2.05) | 2.35*** (1.76–3.14) |

| Occupatione | ||||

| Day laborer/maid | ---- | 1.04* (0.99–1.00) | --- | 1.65*** (1.26–2.18) |

| Family business | 0.97 (1.21–2.80) | 1.18‡ (0.98–1.42) | 0.74** (0.60–0.90) | 1.57*** (1.26–1.96) |

| Own business | 1.37* (1.01–1.85) | 1.60*** (1.31–1.95) | 0.78‡ (0.57–1.04) | 1.18 (0.90–1.55) |

| Household income (log transformed) | 1.00 (0.97–1.10) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.00 (0.96–1.02) | 1.05*** (1.02–1.09) |

| Housingf | 1.16*** (1.08–1.25) | 1.05* (1.01–1.09) | 1.06‡ (0.99–1.14) | 1.08** (1.02–1.14) |

| Assetsg | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.04* (1.01–1.08) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.07** (1.02–1.11) |

| Subjective social status scaleh | 1.04*** (1.02–1.07) | 1.03*** (1.02–1.05) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

Independent multivariate logistic regressions testing whether socio-economic status was significantly associated with soda or alcohol consumption. Age was included in all models but results are not shown.

P<0.10,

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001

Soda consumption: 1 = consumption of more than one carbonated, sugar beverage in the past week

Alcohol consumption: 1=drink alcoholic beverages, even occasionally.

Baseline condition is no education

Baseline condition is not working for women and day laborer for men.

Housing variable (collected in 1997) was developed using principal components analysis summarizing six housing variables (e.g. roof, walls, floor).

Assets variable (collected in 1997) was developed using principal components analysis summarizing twelve asset variables (e.g. television, radio, blender).

Developed by the MacArthur Network on SES and Health. Higher score represents higher level of perceived social status.

Women who had completed secondary school were 2.35 (p<0.0001) times more likely to consume alcohol occasionally than those who had not completed any schooling or those who had only completed some primary school (OR=1.56, p<0.0001, data not shown). In men, there was a non-significant trend for the association between completion of secondary school and alcohol consumption (OR=1.39, p=0.10).

In women, those who worked in a family business (OR=1.57, p<0.0001) or as maids (OR=1.65, p<0.0001) were more likely to drink alcohol than housewives. In men, those in a family business (OR=0.74, p=0.063) or those who owned a business (OR=0.078, p=0.096) were actually less likely to drink alcohol in comparison with day laborers. Income, housing and assets were significantly independently associated with drinking alcohol in women, and there was a non-significant trend for housing status to be positively associated with alcohol consumption in men. The subjective social status scale was not significantly associated with beverage consumption for either gender.

Discussion

BMI was positively associated with SES, regardless of how it was measured – as education, occupation, household income, housing, assets or subjective social status – in a low-income population of adults in rural Mexico. The associations with SES were strongest and most consistent for education and occupation, and for housing and assets, measures that had been obtained in the same households five years previous to the current study; the weakest relationships were evident for household income and subjective social status. When all SES variables were included in the model simultaneously, both of the education contrasts remained significant, the highest occupation contrast remained significant, as did housing conditions and assets in both sexes. Household income and subjective social status did not contribute uniquely to the model.

Women above the median age who had obtained at least a primary education or were in the highest occupation category had the highest prevalence of overweight or obesity (>70%) and a mean BMI between 28 and 29. The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity, particularly in women, has been documented in Mexico and throughout Latin America (Filozof, Gonzalez, Sereday, Mazza, & Braguinsky, 2001; Martorell, Khan, Hughes, & Grummer-Strawn, 1998; Uauy, Albala, & Kain, 2001). In this study, BMI was significantly positively associated with age in women, a trend that has also been noted in Mexican-Americans (Flegal, Ogden, & Carroll, 2004).

Across Mexico as a whole, there is a negative relationship between SES and the prevalence of overweight and obesity (Rivera & Sepúlveda-Amor, 2003). However, within the sample reported here from the bottom quintile of the income distribution, those with the highest BMIs were the most educated, with the best occupations, and the best equipped houses. It is possible to imagine an inverted U-shaped relationship between SES and BMI or obesity across Mexico. Those living in extreme poverty at the far left of the curve may not have the resources to become obese. Those who are slightly richer yet still poor compared with the population as a whole have the resources to maintain positive energy balance over a prolonged period, which is the fundamental biological basis for the development of obesity.

What are the reasons that SES could be positively associated with obesity in this population? There was a significant positive association between BMI and the consumption of both carbonated sugar and alcoholic beverages, while controlling for all SES variables, which confirms previous findings (Malik, Schulze, & Hu, 2006; Wannamethee, Field, Colditz et al., 2004). There was also a positive association between many SES variables and beverage consumption (soda and alcohol) in both sexes. These findings together suggest that increased economic resources may allow people to purchase and consume a larger number of high calorie beverages, which then contribute to weight gain. Thus, in spite of the narrow range of socio-economic variability in this population, the increased consumption of high calorie beverages may explain the positive relationship between SES and BMI in this population

Most studies looking at SES and obesity have interpreted the causal pathway to lead from lower SES to a higher prevalence of obesity (e.g. (Power, Graham, Due, Hallqvist, Joung, Kuh et al., 2005)). The analysis reported here would confirm these findings because housing and asset measures collected five years previous to the current survey contributed significantly to the models independently from current income and occupation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the causality is bidirectional, as suggested by a longitudinal study of the impact of weight gain on net worth in the United States (Zagorsky, 2005). In the context of a low-income developing country, having a higher BMI may be a marker for decreased infection or disease, increased social status or greater resources, which may contribute to a social desirability associated with obesity (Philipson, 2001). In recent studies in South Africa (Faber & Kruger, 2005), the Mediterranean (Tur, Serra-Majem, Romaguera, & Pons, 2005) and the Pacific Islands (Pollock, 1995), obesity was not associated with any negative stigma. Some evidence suggests that as countries become more modernized, there is a shift toward preferences for smaller body sizes (Becker, Gilman, & Burwell, 2005).

Throughout the developing world, intakes of fat, animal products and sugar are increasing simultaneous to decreasing consumption of cereals, fruit and vegetables (Bermudez & Tucker, 2003; Du, Mroz, Zhai, & Popkin, 2004; Kain, Vio, & Albala, 2003). Although there is no evidence from the current study to comment on patterns of food consumption, it is clear that rapid changes have occurred over the past two decades in Mexico in economic development and market globalization, which parallel significant dietary changes (Drewnowski & Popkin, 1997). Traditional bean- and corn-based diets have been substituted for industrialized food with more fat and simple carbohydrates, even in more isolated Mayan populations (Aguirre-Arenas, Escobar-Pérez, & Chávez-Villasana, 1998; Leatherman & Goodman, 2005). Trends at the national level in Mexico suggest that the change in prevalence of overweight and obesity from 1992 to 2000 could be explained just by the increased availability of calories during this time period (Arroyo, Loria, & Méndez, 2004). Between 1992 and 2000 in Mexico, calories (Kcal) per capita per day consumed from carbonated soft drinks increased by 50% and were not as sensitive to increasing prices as other commodities were, suggesting that people had a high willingness to pay for carbonated sugar beverages.

The increasingly widespread availability of carbonated soft drinks, alcoholic beverages and low-cost snack foods in Mexico is likely to be the consequence of many converging forces. The North American Foreign Trade Agreement (NAFTA) contained key elements that resulted in increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) from the US into Mexican food and beverage processing (Hawkes, 2006). FDI has been shown to make processed foods and beverages available to an increasing number of people through lower prices, enhanced distribution channels and increased marketing and advertising. Another factor that could be contributing to the consumption of carbonated sugar beverages, alcohol and processed foods in Mexico is the expansion of supermarkets. Between 1993 and 2004, the number of national chain stores, discounters and convenience stores grew from 700 to 5729 (Snipes, 2004). Although 90% of food purchases in small, rural towns are still conducted at small, family-owned stores or vendors, the amount of goods purchased from these sources is declining year by year (Condessa Consulting, 2005). Given their economies of scale in storage and distribution, supermarkets can sell a much wider variety of processed foods and beverages at lower prices, while also maintaining profits (Reardon, Timmer, Barrett, & Berdegué, 2003).

The study reported here presented data suggesting that within the poorest quintile of the Mexican population, individuals with higher relative SES are more likely to be obese or overweight than those with lower SES, and that this relationship may be mediated by the consumption of carbonated sugar beverages and alcohol. The strength of the study was that the sample was large and representative of the poorest population living in seven states in rural Mexico, which is an under-researched group of critical importance to policy makers. Height and weight were measured by nurses, so the values for BMI were not biased as if they had been self-reported measures. A wide range of measures of SES were collected, including current and past measures, which addresses the recent call for the inclusion of multiple measures of SES (Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Chideya, Marchi, Metzler et al., 2005). In addition, subjective social status was assessed, which has not previously been included in a large survey such as this one.

In spite of these strengths, some clear limitations are evident in the study. First, given that sampling occurred as part of a national house-to-house survey, there were not extensive questions about dietary intake, fitness or other behaviors and beverage consumption was used as a proxy for dietary intake. The measures reported here are not as sensitive as some other studies that measure intake, fitness and other behaviors directly rather than relying on brief self-report. Second, the findings are limited in generalizability to Mexican adults in the poorest segment of the population, because all study participants were from the lowest quintile of the income distribution. Third, sampling occurred during the day when more women than men were likely to be home, and thus women were over-sampled. Of these women, the majority were housewives, which means that the “occupation” variable did not have substantial variation. However, a wide range of other measures of SES were included with the intention of capturing variability for women who were not working outside the home at the time of the survey. Fourth, the adults in this survey were all parents or guardians of at least one child 2–6 years old, and thus may not be representative of the childless adult population or of parents of older children in Mexico. Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of the design, it is not possible to comment substantially on the causal relations among variables. However, we do have two measures from five years previous to the current survey providing some longitudinal context.

Interventions to prevent and treat overweight and obesity and to assist individuals with weight control are urgently needed in Mexico, especially among economically vulnerable segments of the population. There is a portion of the population – the more affluent and health-conscious – who already demand diet products including low-carbohydrate and sugar-free foods and beverages (Kelly, 2005). However, these foods and fads are not likely to be accessible, nor necessarily appealing, to the rural poor. The findings presented here suggest that it is important to consider the issues and concerns of low-income populations separately from those of the country as a whole. The data also suggest within the poorest quintile of the population, women, particularly those who are older and have received some primary education, are a critical group to target when designing and developing interventions to address obesity.

Unfortunately, little is known about the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity on a population level (Jeffery, 2001), particularly in developing countries. A related challenge is that transitional economies are facing the dual burden of under-nutrition simultaneous with a high prevalence of obesity (Caballero, 2005; Doak, Adair, Bentley, Monteiro, & Popkin, 2005), a trend that was first identified several years ago in South Africa (Steyn, Bourne, Jooste, Fourie, Rossouw, & Lombard, 1998). The prevalence of the coexistence of a stunted child and an overweight mother in the same household ranges from 2.2 to 13.4% in nationally representative samples from countries in Latin America (Garrett & Ruel, 2005). In Mexico, most resources relating to public health nutrition are utilized for the prevention of undernutrition and anemia rather than for addressing obesity (Rivera & Sepúlveda-Amor, 2003), although some promising new interventions are emerging (Jimenez-Cruz, Loustaunau-Lopez, & Bacardi-Gascon, 2006). In spite of the apparent conflict facing policy makers, there are already some examples of the effective integration of obesity prevention into nutrition programs in transitional economies (Uauy & Kain, 2002). Education to promote physical activity and emphasize moderation in the consumption of energy dense foods such as sweetened carbonated beverages and alcohol will be as important in the developing world as in the United States. Considering the larger context of social, political and environmental factors will also be critically important in addressing this important public health issue.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to A Franco, R Shiba, F Papaqui, JP Gutierrez, G Olaiz, L Neufeld and S Bertozzi at the Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica, P Gertler and D Levine at the University of California, Berkeley, and N Adler at the University of California, San Francisco, to the nurses who collected the data, and to the editors and anonymous reviewers of this journal for very helpful suggestions. For financial support, thanks to the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the Fogarty International Center at NIH, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health”, and the Mexican Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar-Salinas CA, Velazquez Monroy O, Gomez-Perez FJ, Gonzalez Chavez A, Esqueda AL, Molina Cuevas V, Rull-Rodrigo JA, Tapia Conyer R. Characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes in Mexico: Results from a large population-based nationwide survey. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(7):2021–2026. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Arenas J, Escobar-Pérez M, Chávez-Villasana A. Evaluation of food intake and nutrition in four rural communities. Salud Publica Mex. 1998;40:398–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo P, Loria A, Méndez O. Changes in the household calorie supply during the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico and its implications for the obesity epidemic. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(7):s163–s168. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera S, Rivera J, Espinosa-Montero J, Safdie M, Campirano F, Monterrubio E. Energy and nutrient consumption in Mexicon women 12–49 years of age: analysis of the National Nutrition Survey 1999. Salud Pub Mex. 2003;(Suppl 4):S530–539. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342003001000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Gilman SE, Burwell RA. Changes in prevalence of overweight and in body image among Fijian women between 1989 and 1998. Obes Res. 2005;13:110–117. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JR, Todd PE. A report on the sample sizes used for the evaluation of the education, health and nutrition program (PROGRESA) of Mexico. Washington D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute; 1999a. Available at www.ifpri.org. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JR, Todd PE. Randomness in the experimental samples of PROGRESA (education, health and nutrition program) Washington D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute; 1999b. Available at www.ifpri.org. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Trends in dietary patterns of Latin American populations. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19(Suppl 1):S87–99. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B. A nutrition paradox -- underweight and obesity in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(15):1514–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. 3. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Condessa Consulting, C. Mexico’s Retail Food Sector: GAIN Report Number MX5303. Washington D.C.: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24:794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak CM, Adair LS, Bentley M, Monteiro C, Popkin BM. The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:129–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev. 1997;55(2):31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S, Mroz TA, Zhai F, Popkin BM. Rapid income growth adversely affects diet quality in China-particularly for the poor! Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(7):1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber M, Kruger HS. Dietary intake, perceptions regarding body weight, and attitudes toward weight control of normal weight, overweight, and obese Black females in a rural village in South Africa. Ethn Dis. 2005 Spring;15(2):238–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J, Namazie C. Measuring health and poverty: a review of approaches to identifying the poor. London: DFID (Department for International Development) Health Systems Resource Centre; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald LC, Gutierrez JP, Neufeld LM, Mietus-Snyder M, Olaiz GO, Bertozzi SM, Gertler PJ. High prevalence of obesity among the poor in Mexico. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2544–2545. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data--or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filozof C, Gonzalez C, Sereday M, Mazza C, Braguinsky J. Obesity prevalence and trends in Latin-American countries. Obes Rev. 2001;2(2):99–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence and trends in overweight in Mexican-american adults and children. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(7 Pt 2):S144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett J, Ruel MT. The coexistence of child undernutrition and maternal overweight: prevalence, hypotheses, and programme and policy implications. Matern Child Nutr. 2005;1(3):185–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2005.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Adler NE, Kawachi I, Frazier AL, Huang B, Colditz GA. Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E31. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habicht JP. Estandarización de métodos epidemiológicos cuantitativos sobre el terreno [Standardization of quantitative epidemiological methods in the field] Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1974 May;76(5):375–384. Article in Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. Uneven dietary development: linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Globalization and Health. 2006;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Catenacci VA, Wyatt HR. Obesity: Etiology. In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins R, editors. Modern nutrition in health and disease. 10. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 1013–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, Adler NE, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Seeman TE. Relationship Between Subjective Social Status and Measures of Health in Older Taiwanese Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(3):483–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW. Public health strategies for obesity treatment and prevention. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):252–259. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.3.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Cruz A, Loustaunau-Lopez VM, Bacardi-Gascon M. The use of low glycemic and high satiety index food dishes in Mexico: a low cost approach to prevent and control obesity and diabetes. Nutr Hosp. 2006;21(3):353–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain J, Vio F, Albala C. Obesity trends and determinant factors in Latin America. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19(Suppl 1):S77–86. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly T. Slimming down. Business Mexico. 2005;14:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman TL, Goodman A. Coca-colonization of diets in the Yucatan. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:833–846. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre S, McKay L, Der G, Hiscock R. Socio-economic position and health: what you observe depends on how you measure it. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2003;25:288–294. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdg089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight-gain: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Kogevinas M, Elston MA. Social/Economic Status and Disease. Annual Review of Public Health. 1987;8:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell R, Khan LK, Hughes ML, Grummer-Strawn LM. Obesity in Latin American women and children. J Nutr. 1998;128(9):1464–1473. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.9.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Brock K. From poverty assessment to policy change: processes, actors and data. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Lu B, Popkin BM. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, Popkin B. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(2):940–946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MR, Gragnolati M, Burke KA, Paredes E. Measuring Living Standards with Proxy Variables (in Measurement and Error) Demography. 2000;37(2):155–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser CON. The Asset Vulnerability Framework: Reassessing Urban Poverty Reduction Strategies. World Development. 1998;26(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Philipson T. The world-wide growth in obesity: an economic research agenda. Health Econ. 2001;10:1–7. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200101)10:1<1::aid-hec586>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock NJ. Cultural elaborations of obesity: fattening practices in Pacific societies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 1995;4:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Graham H, Due P, Hallqvist J, Joung I, Kuh D, Lynch J. The contribution of childhood and adult socioeconomic position to adult obesity and smoking behaviour: an international comparison. International Journal of Edipemiology. 2005;34:335–344. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon T, Timmer CP, Barrett CB, Berdegué J. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2003;85(5):11401146. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera JA, Sepúlveda-Amor J. Conclusions from the Mexican National Survey 1999: translating results into nutrition policy. Salud Pub Mex. 2003;45(Suppl 4):S565–S575. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342003001000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche AF, Siervogel RM, Chumlea WC, Webb P. Grading body fatness from limited anthropometric data. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:2831–2838. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.12.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzem B, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of Type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292(8):927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Clarke P, Marmot M. Multiple measures of socioeconomic position and psychosocial health: proximal and distal measures. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:1192–1199. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipes K. Gain Report MX 4313. Washington D.C.: United States Foreign Agricultural Service; 2004. Mexico Exporter Guide: Annual 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Stunkard A. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psych Bull. 1989;106:260–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn K, Bourne L, Jooste P, Fourie JM, Rossouw K, Lombard C. Anthropometric profile of a black population of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(1):35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Smith GD. Patterns, distribution, and determinants of under- and overnutrition: a population-based study of women in India. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):633–640. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tur JA, Serra-Majem L, Romaguera D, Pons A. Profile of overweight and obese people in a mediterranean region. Obes Res. 2005 Mar;13(3):527–536. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy R, Albala C, Kain J. Obesity trends in Latin America: transitioning from under- to overweight. J Nutr. 2001;131(3):893S–899S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.893S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy R, Kain J. The epidemiological transition: need to incorporate obesity prevention into nutritional programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):223–229. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG. Alcohol, body weight, and weight gain in middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(5):1312–1317. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Field AE, Colditz GA, Rimm EB. Alcohol intake and 8-year weight gain in women: a prospective study. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1386–1396. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Technical Report Series, No 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. Physical Status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry; pp. 8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting health life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(6):816–820. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorsky JL. Health and wealth: The late-20th century obesity epidemic in the U.S. Economics and Human Biology. 2005;3:296–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes Res. 2004a;12(10):1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Social Science & Medicine. 2004b;58(6):1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]