Introduction

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rare, locally infiltrative mesenchymal tumor found usually in women of reproductive age, and was first described by Steeper and Rosai[1] in 1983. It is a slow-growing, low-grade neoplasm involving the pelvis and perineum with a high risk for local recurrence, which occurs after many years. Therefore, initial surgical resection with wide margins followed by long-term surveillance is advised. Many options for the treatment of recurrences have been tried with varying success, but no single modality is clearly beneficial over others. Extensive and repetitive surgeries are associated with increased morbidity. Current research does not support the earlier quoted dictum of initial excision with “wide surgical margins,” as the recurrence rate in patients with narrow surgical margins is not higher than that of patients with wide surgical margins.[2] Estrogen and progesterone receptors are commonly found in aggressive angiomyxoma, and so they may be hormone-dependent.[2–6] Hence, they are likely to grow during pregnancy and respond to hormonal manipulation. However, only a few cases of its detection and management during pregnancy are reported in the literature.[2, 4–6] A primigravida with aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva excised at 16 weeks of gestation is reported with the aim to discuss management options and subsequent follow-up.

Case Report

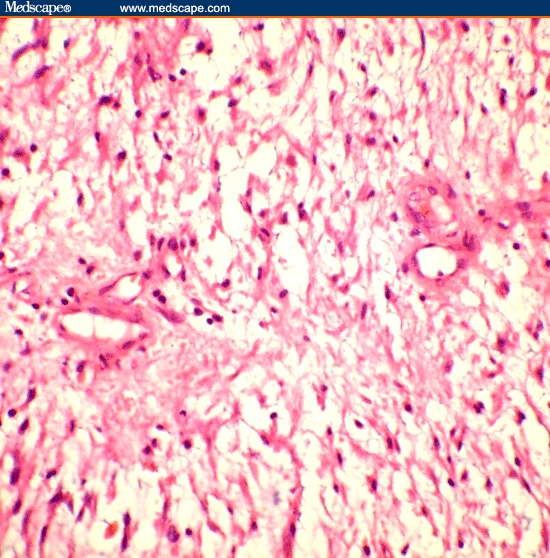

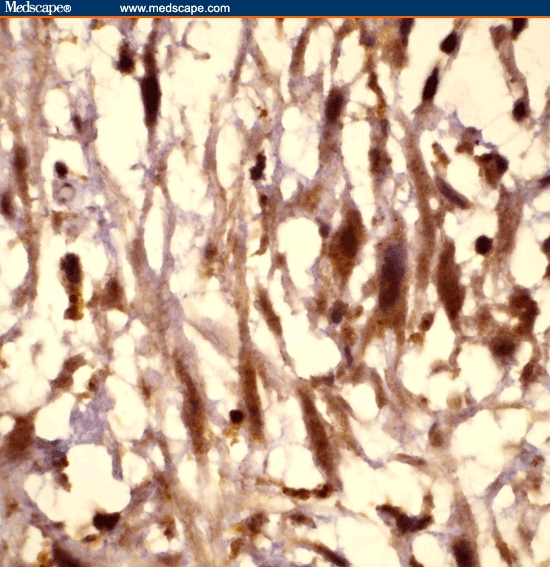

We report on a 25-year-old primigravida who after an excisional biopsy of a vulvar swelling was diagnosed with aggressive angiomyxoma. She had noticed a 2-cm, soft, painless swelling in the right labium majus at 12-week gestation without any signs of inflammation. Four weeks later, it doubled in size and she had difficulty walking. It was excised under local anesthesia (at 16 weeks) at a private clinic. There was profuse bleeding during the procedure, which was controlled with sutures and pressure bandage. Histopathology revealed whirling bundles of spindle-shaped cells with stellate cells in a myxoid background. Mild atypia was present with no mitosis. Many capillary-sized blood vessels were seen, which were thick-walled. Perivascular collagen condensation was also noted (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for desmin and estrogen receptor but negative for progesterone receptor (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma. A differential diagnosis of angiofibroblastoma was considered because we did not have the complete tumor to comment on the surgical margins, as it was excised elsewhere and only the block and slides were available for review. However, we diagnosed it as an aggressive angiomyxoma because we found estrogen receptor positivity and thick-walled vessels, and both of these features are consistent with an aggressive angiomyxoma.

Figure 1.

Tissue section from the right labial mass shows thick-walled capillary channels and spindle-shaped to stellate cells embedded in a myxoid background. Perivascular collagen condensation is also noted, hematoxylin and eosin 400x.

Figure 2.

Tissue section showing cells depicting the strong estrogen receptor positivity of the mass, immunoperoxidase 1000x.

All subsequent clinical examinations were normal and no growth was palpable. Labor was induced at 39 weeks for gestational hypertension, and she gave birth to a healthy baby girl (weight, 2.7 kg). A right mediolateral episiotomy did not result in untoward hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis 6 weeks later showed no residual tumor. She was normal at follow-up 9 months later.

Discussion

Aggressive angiomyxoma occurs almost exclusively in the pelvic and perineal regions of women of reproductive age, but is occasionally reported in men (male-to-female ratio, 1:6).[2] The pathogenesis is unclear, but recently a translocation at chromosome 12 with a consequent aberrant expression of the high-mobility group protein isoform I-C (HMGIC) protein involved in DNA transcription was demonstrated.[7]

It presents as a slow-growing vulvar mass, perineal hernia, vaginal polyp, or endometrial polyp. It is soft and easily compressible. It has no capsule, can invade the paravaginal and pararectal spaces displacing the pelvic organs, and may extend retroperitoneally. Clinically, it may be diagnosed as a Bartholin cyst, lipoma, labial cyst, Gartner duct cyst, levator hernia, or sarcoma. Also, clinically it is difficult to differentiate this tumor from other mesenchymal tumors occurring in this region, such as liposarcoma and myxoid leiomyosarcoma. Usually the diagnosis is made on histopathology.

The cut surface has a glittering homogeneous gray appearance with focal areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Microscopically, there is loosely textured myxoid stroma with small clusters of mesenchymal, stellate cells, and spindle-shaped cells. Neoplastic cells are considered to be derived from the stromal cells, which express fibroblastic or myofibroblastic features. It has a prominent vascular pattern in which the dilated vessels of varying sizes are distributed haphazardly in a myxoid background. Fingerlike projections are seen at the periphery and into the surrounding tissue without necessarily infiltrating the adjacent organs, such as the rectum and bladder. Mitotic figures are absent. Immunohistochemistry is positive for desmin, vimentin, and smooth muscle actin. Estrogen and progesterone receptors may be positive.[8] Differential diagnoses to be considered by the pathologist are angiomyofibroblastoma and other myxoid tumors, such as malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), which occur in women of reproductive age and are commonly found in the vulva. They may be clinically similar and have some histologic and immunohistochemical characteristics that are similar to the aggressive angiomyxoma. Aggressive angiomyxoma is an infiltrative tumor, whereas the angiomyofibroblastoma is well circumscribed. (This characteristic can be identified on MRI also). Also, the aggressive angiomyxoma has thick-walled vessels, which are less numerous than the thin-walled vessels in angiomyofibroblastoma. MFH can often infiltrate along the fascial planes; contains abundant acid mucin; and features spindled, stellate, and multinucleated giant cells with random (patternless) storiform growth patterns. They tend to show pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and mitotic activity greater than observed in aggressive angiomyxoma. MFH also features a complex, delicate pattern of a network of curvilinear branching capillaries, which is almost uniformly absent, or never more than a focal finding in aggressive angiomyxoma.[9]

Imaging studies are important to determine the extent and surgical approach. The tumor has a well-defined margin and attenuation less than muscle on a computed tomographic (CT) scan. A “swirled” internal pattern may also be found. On MRI, it is isointense relative to muscle on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with contrast enhancement on a gadolinium scan. The attenuation on CT and high signal intensity on MRI may be because of its loose myxoid matrix and high water content.[10]

Wide surgical excision is the traditional treatment of choice. Complete excision may require removal of the adjacent fascia and muscles. However, organs, such as the rectum and bladder to which the tumor may be attached, are spared as the morbidity of extensive surgery may not be justified due to its high recurrence rate even after complete resection. Where fertility is to be preserved or surgery is likely to be extensive and mutilating, incomplete resection is acceptable as local recurrences can be treated with further resection.[11] If the tumor extends above the pelvic diaphragm, an abdominal-perineal approach may be required. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are considered less suitable options due to low mitotic activity.

As this tumor mainly occurs in the reproductive age and seems to grow during pregnancy, there may be a hormone dependency. This is corroborated by its estrogen and progesterone receptor positivity. There are only a few cases reported about its coexistence with pregnancy. Fishman and colleagues[4] reported a weak estrogen and negative progesterone receptor activity in a 37-year-old black woman who was not pregnant at the time of diagnosis but who had a recurrence later during pregnancy. Htwe and colleagues[5] reported a 41-year-old woman with a “Bartholin cyst” excised during pregnancy that was reported later as aggressive angiomyxoma with positive progesterone and negative estrogen receptors. Wolf and colleagues[6] reported a primigravida with vulvar aggressive angiomyxoma (initially suspected to be condylomata) excised at 36 weeks of gestation followed by vaginal delivery and no recurrence 9 months later. It was positive for estrogen and negative for progesterone receptor activity.[6] Han-Geurts and colleagues[2] reported 3 cases associated with pregnancy; all were managed with resection with narrow margins, and one also received adjuvant radiation therapy.[2] Positive resection margins during pregnancy may be managed expectantly, as the hormone changes after delivery may affect tumor growth. However, regrowth may occur during the ongoing pregnancy or during a subsequent pregnancy.[2]

Hormonal manipulation with tamoxifen, raloxifene, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRH agonists) has been attempted, but their role is not clearly defined. These have been shown to reduce the tumor size and may help to make complete excision feasible in large tumors and in the treatment of recurrence.[11–14] Due to its association with hormonal receptors, hormonal methods of contraception may not be suitable, but no evidence either to support or to negate this statement exists in the literature.[2]

Recurrence is frequent in about 30% to 40%, and may occur from months to several years after excision (2 months to 15 years).[15] The high recurrence rate may partially be due to inadequate excision, which may be due to an incorrect initial diagnosis.

Another treatment modality described is angiographic embolization of the aggressive angiomyxoma. This may help in subsequent resection by shrinking the tumor as well as making it easier to identify from surrounding normal tissues.[2,16] However, recurrences after initial response to embolization may occur as the tumor may already have or develop blood supply from alternate blood vessels.[2] In case of large tumors needing extensive resection, arterial embolization and/or hormonal treatment may be used initially followed by surgical resection, with narrow surgical margins being acceptable. Resection with wide margins does not appear to reduce recurrences when compared with narrow margins or even incomplete resection.[2,11]

Usually this tumor is nonmetastasizing, but there are 2 reports with multiple metastases in women treated initially by excision and who later succumbed to metastatic disease. A 63-year-old woman with aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvis had pulmonary, peritoneal, and lymph node (mediastinal, iliac, and aortic) metastases, ending in death.[17] A 27-year-old woman with multiple local recurrences (6 and 7 years after resection) had pulmonary metastases 2 years later, and she died a year later.[18]

As late recurrences are known, all patients need to be counseled about the need for long-term follow-up. Periodic clinical examination may be insufficient to detect recurrence. Imaging studies, such as MRI, may detect recurrence early, but there are no guidelines about their frequency. Early detection will help as the tumor will be smaller in size and surgery may be simpler to perform. Complete excision with less morbidity will be easier in a smaller tumor than in a larger tumor, which is locally infiltrative. This woman has been advised regular checkups, with a plan for repeat excision or treatment with GnRH agonists or embolization in case of recurrence.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at rashmibagga@gmail.com or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Rashmi Bagga, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), Sector 12, Chandigarh, India.

Anish Keepanasseril, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), Sector 12, Chandigarh, India.

Vanita Suri, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), Sector 12, Chandigarh, India.

Raje Nijhawan, Department of Pathology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), Sector-12, Chandigarh, India Author's Email: rashmibagga@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Steeper TA, Rosai J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:463–475. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han-Geurts IJ, van Geel AN, van Doorn L, den Bakker M, Eggermont AM, Verhoef C. Aggressive angiomyxoma: multimodality treatments can avoid mutilating surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:1217–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin CH, Liu CC, Kang WY, et al. Huge aggressive angiomyxoma: a case report and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:301–304. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman A, Otey LP, Poindexter AN, Shannon RL, Gritanner RE, Kaplan Al. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvis and perineum. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Htwe M, Deppisch LM, Saint-Julien JS. Hormone-dependent, aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:697–699. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf CA, Kurzeja R, Fietze E, Buscher U. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female perineum in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:484–485. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magtibay PM, Salmon Z, Keeney GL, Podratz KC. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum: a case series. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCluggage WG, Patterson A, Maxwell P. Aggressive angiomyxoma of pelvic parts exhibits estrogen and progesterone receptor positivity. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:603–605. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.8.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Lefkowitz M, Kindblom LG, Meis-Kindblom JM. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer. 1996;78:79–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960701)78:1<79::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Outwater EK, Marchetto BE, Wagner BJ, Siegelman ES. Aggressive angiomyxoma: findings on CT and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:435–438. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan YM, Hon E, Ngai SW, Ng TY, Wong LC, Chan IM. Aggressive angiomyxoma in females: is radical resection the only option? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:216–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks SE, Balidimos I, Reuter KL, Khan A. Virtual consult – aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: impact of GnRH agonist. Medscape Womens Health. 1998;3:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCluggage WG, Jamieson T, Dobbs SP, Grey A. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: dramatic response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:623–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirier M, Fraser R, Meterissian S. Case 1: aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvis: response to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3535–3536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behranwala KA, Thomas JM. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a distinct clinical entity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:559–563. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner E, Shadmand-Fischer S, Schunk K, et al. Perineal excision of a large angiomyxoma in a young woman following magnetic resonance and angiographic imaging. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:568–570. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siassi RM, Papadopoulos T, Matzel KE. Metastasizing aggressive angiomyxoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;2:1772. doi: 10.1056/nejm199912023412315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blandamura S, Cruz J, Faure Vergara L, Machado Puerto I, Ninfo V. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a second case of metastasis with patient's death. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1072–1074. doi: 10.1053/s0046-8177(03)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]