Abstract

Insomnia impairs daytime functioning or causes clinically significant daytime distress. The consequences of insomnia, if left untreated, may contribute to the risks of developing additional serious conditions, such as psychiatric illness, cardiovascular disease, or metabolic issues. Furthermore, some comorbidities associated with insomnia may be bidirectional in their causality because psychiatric and other medical problems can increase the risk for insomnia. Regardless of the serious consequences of inadequately treated insomnia, clinicians often do not inquire into their patients' sleep habits, and patients, in turn, are not forthcoming with details of their sleep difficulties. The continuing education of physicians and patients with regard to insomnia and currently available therapies for the treatment of insomnia is, therefore, essential. Insomnia may present as either a difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or waking too early without being able to return to sleep. Furthermore, these symptoms often change over time in an unpredictable manner. Therefore, when considering a sleep medication, one with efficacy for the treatment of multiple insomnia symptoms is recommended. A modified-release formulation of zolpidem, zolpidem extended-release, has been approved for the treatment of insomnia characterized by both difficulty in falling asleep and maintaining sleep. Here, we review studies supporting the use of zolpidem extended-release in the treatment of sleep-onset and sleep maintenance difficulties.

Introduction

Insomnia symptom presentation includes difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or waking too early without being able to return to sleep,[1] causing clinically significant daytime distress or functional impairment in social, occupational, and/or other important areas of functioning.[2] When it becomes chronic, insomnia has the potential to develop into more serious conditions; for example, studies have demonstrated that insomnia patients may be at an increased risk for cardiac morbidity, ischemic stroke,[3] glucose intolerance, weight gain, and psychiatric disturbances.[4,5] Patients may also experience overall reductions in quality of life, cognitive and occupational functioning, and incur excess healthcare utilization.[6–8]

Comorbidities that exist with insomnia are often bidirectional: Not only does insomnia increase the odds of developing psychiatric and medical problems, but the latter two can increase the likelihood of insomnia.[9] In addition, major depression, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, stress, grief, medication side effects, alcohol consumption, noise, and poor sleeping environment are seen more often in patients with insomnia. In patients with depression, sleep problems may appear months before the diagnosis of clinical depression and persist after the resolution of depression; emerging evidence indicates that managing insomnia symptoms may augment the treatment of this comorbid disease.[10,11] Therefore, it behooves the clinician to investigate the sleep habits of patients as a matter of routine.

Patients often do not volunteer information with regard to their sleep disturbances with their physicians, even though surveys of primary care patients consistently report that the majority of patients experience some form of sleep difficulty.[12] This may be due to the fact that insomnia is often viewed by patients as a bad habit that they should be able to remedy on their own, and the perception that insomnia has no serious causes or consequences. Moreover, insomnia underrecognition is further promoted by physicians' reluctance to inquire about their patients' sleep habits. This is, for the most part, due to a lack of specific insomnia knowledge among primary care physicians.[13] Hence, continuing education of physicians and patients on insomnia and currently available therapies is essential for best practice. This should lead to more inquiries about patients' sleep situations and habits in the primary care setting, particularly in instances in which sleep problems could exist, ie, in the acute setting, in follow-up visits for chronic problems, and during complete medical evaluation.

Over-the-counter antihistamines, herbal products, and self-medication with alcohol are common methods used by patients suffering from insomnia, regardless of problems with safety and a lack of proven efficacy for these agents in insomnia.[1] Although some patients visit their clinicians after failing with these treatments, the majority do not, and may continue to self-medicate ineffectively for long periods of time, only presenting to a clinician when their condition has become chronic.[14]

Patients often suffer from more than 1 insomnia symptom (ie, difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or awaking too early), the variability and intensity of which can evolve unpredictably over time.[15,16] Therefore, it may be important to consider the efficacy for sleep onset as well as sleep maintenance, when selecting a sleep medication. However, many current treatment options (such as zaleplon [Sonata] and zolpidem [Ambien]) only have efficacy for sleep-onset difficulties. A modified-release formulation of zolpidem tartrate, zolpidem extended-release (Ambien CR; also referred to as zolpidem modified-release in previous literature), is approved for the treatment of insomnia associated with sleep-onset and/or sleep maintenance difficulties, with the potential to provide clinical benefits beyond that of the original immediate-release formulation of zolpidem. An overview of the data supporting the use of zolpidem extended-release for the management of insomnia is presented here. In particular, efficacy in promoting both sleep onset and sleep maintenance is described in both healthy volunteers and adult and elderly patients with chronic primary insomnia.

Development of an Extended-Release Formulation of Zolpidem

Original zolpidem is effective for sleep onset, but has not consistently been shown to improve sleep maintenance.[17–19] This has led to the development of an extended-release formulation of zolpidem, to maintain plasma concentrations through the middle of the night. Unlike the original zolpidem formulation, zolpidem extended-release does not have any recommended limitations on duration of use; therefore, it can be prescribed as long as medically necessary.

Zolpidem extended-release is a 2-layer, biphasic tablet: One layer releases approximately 60% of the dose immediately, whereas the second layer releases the remainder of the drug content at a slower rate. As a result, plasma concentrations are maintained for a longer period of time. This is confirmed by an increase in plasma levels beyond 3 hours post dose compared with the immediate-release zolpidem formulation.[20] Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses have also demonstrated that zolpidem extended-release has a rapid onset of action and elimination half-life of 2.8 hours in adults and 2.9 hours in elderly individuals, which is similar to the pharmacokinetic properties of original zolpidem. Consistent with these elimination characteristics, at 8 hours post dose no differences were observed between zolpidem extended-release and placebo-treated subjects on measures of psychomotor and cognitive performance, indicating a lack of morning residual sedation in healthy volunteers.[21,22]

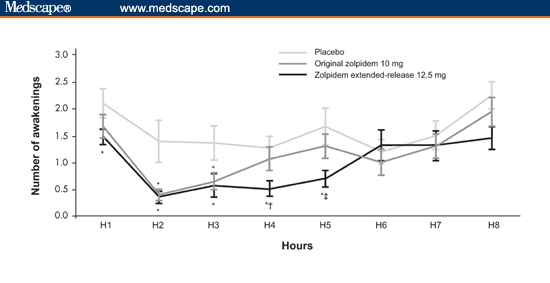

The improved hypnotic profile of zolpidem extended-release is supported by studies in healthy volunteers with models of insomnia. In a traffic noise model of sleep disturbance, which involves exposing the subject to audible traffic noise throughout the entire night to disturb sleep, zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg significantly reduced the number of awakenings (wakeful events lasting ≥ 15 seconds) up to 5 hours post dose compared with placebo. In contrast, original zolpidem 10 mg only provided efficacy for reduced awakenings up to 3 hours in the same study (Figure 1).[23,24]

Figure 1.

Number of awakenings by hour (manual reading, 30-second cutoff) in healthy subjects, placebo vs zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg and original zolpidem 10 mg. Key: *P < .05 vs placebo, †P < .05 zolpidem extended-release vs original zolpidem, and ‡P = .0542 zolpidem extended-release vs original zolpidem. With permission from CNS Drugs.[24] Copyright 2006, Adis International.

In a model of sleep maintenance disturbance involving scheduled nocturnal awakenings at 3, 4, or 5 hours post dose (separate treatment nights) and a presentation of noise to disturb the return to sleep, zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg significantly decreased the time to return to persistent sleep compared with original zolpidem 10 mg at both 4 and 5 hours post dose. This is consistent with the sustained plasma concentration of zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg beyond 3 hours post dose.[25]

Zolpidem extended-release has a safety profile comparable to original zolpidem. In healthy adult (12.5 mg) and elderly (≥ 65 years; 6.25 mg and 12.5 mg [double the recommended dose in the elderly]) subjects, zolpidem extended-release did not significantly affect psychomotor and cognitive performance 8 hours post dose compared with placebo, on the basis of neurocognitive tests of vigilance and motor and memory.[21,22]

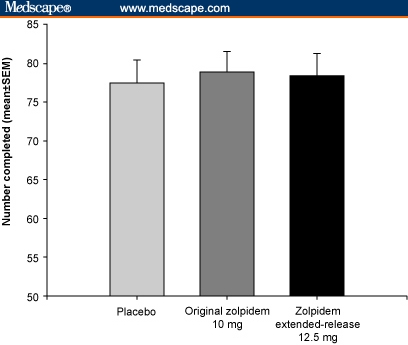

The impact of zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg on next-day cognitive and psychomotor performance was compared with immediate-release zolpidem and placebo in a separate, crossover study. Zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg had no significant effect on psychomotor and cognitive tests at 8 and 9 hours post dose compared with both placebo and zolpidem (Figure 2 and Table).[23]

Figure 2.

Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) (performed 8 hours post dose) – a measure of attention and sedation. Subjects are presented with rows of blank squares paired with randomly assigned numbers. In a defined time period, they are required to substitute digits with a different, corresponding nonsense symbol, the key to which is provided: no significant difference in DSST scores between groups (SEM = standard error of the mean). With permission from Pharmacotherapy.[23] Copyright 2005, Pharmacotherapy Publications.

Table 1.

Psychomotor and Cognitive Test Results (8 Hours Postnocturnal Dosing)

| Parameter, Unit (SEM) | Placebo | Original Zolpidem 10 mg | Zolpidem Extended-Release 12.5 mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFF, hertz – measure of attention and sedation. Subjects are required to discriminate flicker from fusion, and vice versa, in a set of 4 light-emitting diodes arranged in a 1-cm square. | 30.88 (0.47) | 30.74 (0.48) | 30.53 (0.46) |

| WRd, number correct – measure of delayed memory. Subjects are given 2 minutes to learn a list of 20 words. Thirty minutes after this learning period, subjects are given a 2-minute free-recall period, during which they write down as many of the words as they can remember. | 11.09 (0.91) | 10.11 (0.80) | 10.21 (0.80) |

| WRi, number correct – measure of immediate memory. Subjects are given 2 minutes to learn a list of 20 words immediately followed by a 2-minute free-recall period, during which they write down as many of the words as they can remember. | 15.26 (0.65) | 14.83 (0.67) | 14.91 (0.62) |

| CRT total reaction time, milliseconds – measure of attention and sedation. Subjects are required to extinguish 1 of 6 equidistant red lights by pressing an associated response button as quickly as possible. | 605.58 (17.69) | 617.64 (17.87) | 619.56 (17.98) |

SEM = standard error of mean; CFF = critical flicker fusion frequency; WRd = delayed word recall; WRi = immediate word recall; CRT = choice reaction time Adapted from Hindmarch et al[23]

Zolpidem extended-release has also demonstrated efficacy in inducing and maintaining sleep in studies of adult and elderly patients with primary insomnia. In two 3-week studies, zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg improved sleep maintenance by significantly reducing wake time after sleep onset (a sleep maintenance assessment of the amount of time spent awake after initially falling asleep, measured by polysomnography) during the first 6 hours of sleep in both young and elderly adults with insomnia.[26,27] Compared with placebo, zolpidem extended-release also significantly reduced latency to persistent sleep, both at the start and after 2 weeks of double-blind therapy in young adult and elderly patients. Furthermore, in a long-term study (24 weeks) in patients with chronic primary Insomnia, zolpidem extended-release taken up to 7 nights per week demonstrated sustained improvements in sleep onset and sleep maintenance, as measured by patient and clinical global impression scales.[28]

There are a minimal number of drug-drug interactions with zolpidem extended-release, and, although they are well characterized, the pharmacology of any central nervous system-active drug should be considered prior to administration.

Conclusions

It is important that primary care physicians have a high level of suspicion for the presence of insomnia in their patients, and appropriately identify and treat those individuals. When a hypnotic medication is chosen for treatment, generally patients should be managed with effective medication that will adequately treat the symptoms of insomnia without negatively affecting next-morning cognitive and psychomotor performance. Zolpidem extended-release improves upon the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of original zolpidem, maintaining drug levels through the middle of the night for a sleep maintenance benefit in both healthy volunteers and patients with insomnia, while retaining comparable efficacy for sleep induction and similar elimination characteristics to original zolpidem, to keep the risk for next-day effects to a minimum.

Identifying those patients at greatest risk for insomnia is also essential, including those suffering from other conditions, such as major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, chronic pain, and chronic medical conditions. Because insomnia symptoms may change over time in the same patient, a therapy that addresses both sleep induction and sleep maintenance symptoms, such as zolpidem extended-release, may manage insomnia more effectively.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Megan Bridges, MSc, for her editorial assistance, which was funded by sanofi-aventis.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at HyeDoc@pol.net or to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults, June 13–15, 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elwood P, Hack M, Pickering J, Hughes J, Gallacher J. Sleep disturbance, stroke, and heart disease events: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:69–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Newman AB, et al. Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863–867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idzikowski C. Impact of insomnia on health-related quality of life. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;10(suppl1):15–24. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199600101-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth T, Roehrs T, Vogel G. Zolpidem in the treatment of transient insomnia: a double-blind, randomized comparison with placebo. Sleep. 1995;18:246–251. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cricco M, Simonsick EM, Foley DJ. The impact of insomnia on cognitive functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1185–1189. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riemann D, Berger M, Voderholzer U. Sleep and depression – results from psychobiological studies: an overview. Biol Psychol. 2001;57:67–103. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone co-administered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1052–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stepanski EJ, Rybarczyk B. Emerging research on the treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shochat T, Umphress J, Israel AG, Ancoli-Israel S. Insomnia in primary care patients. Sleep. 1999;22(suppl 2):S359–S365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winkelman JW. A primary care approach to insomnia management. Medscape. Copyright 2005. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewprogram/3807_index Accessed January 3, 2007.

- 14.Leger D, Poursain B. An international survey of insomnia: under-recognition and under-treatment of a polysymptomatic condition. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1785–1792. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hohagen F, Kappler C, Schramm E, Riemann D, Weyerer S, Berger M. Sleep onset insomnia, sleep maintaining insomnia and insomnia with early morning awakening – temporal stability of subtypes in a longitudinal study on general practice attenders. Sleep. 1994;17:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse DJ, Finn L, Young T. Onset, remission, persistence, and consistency of insomnia symptoms over 10 years: longitudinal results from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study (WSCS) Sleep. 2004;27:A268. Abstract 602. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, Walsh JK. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:192–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey II. Sleep. 1999;22(suppl 2):S354–S358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg RP. Sleep maintenance insomnia: strengths and weaknesses of current pharmacologic therapies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18:49–56. doi: 10.1080/10401230500464711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinling E, McDougall S, Andre F, Bianchetti G, Dubruc C, Krupka E. Pharmacokinetic profile of a new modified release formulation of zolpidem designed to improve sleep maintenance. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blin O, Micallef-Roll J, Audebert C, Legangneux E. A double-blind, placebo- and flurazepam-controlled investigation of the residual psychomotor and cognitive effects of modified release zolpidem in young healthy volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:284–289. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000218985.07425.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hindmarch I. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the residual psychomotor and cognitive effects of zolpidem-MR in healthy elderly volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02705.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hindmarch I, Stanley N, Legangneux E, Emegbo S. Zolpidem modified-release 12.5 mg improves measures of sleep continuity in a model of sleep disturbance (traffic noise) compared with standard zolpidem 10 mg. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1504. Abstract 321. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moen MD, Plosker GL. Zolpidem extended-release. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:419–426. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hindmarch I, Stanley N, Legangneux E, Emegbo S. Zolpidem modified-release significantly reduces latency to persistent sleep 4 and 5 hours postdose compared with standard zolpidem in a model assessing the return to sleep following nocturnal awakening. Sleep. 2005;28(suppl):A245. Abstract 0731. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roehrs T, Soubrane C, Walsh J, Roth T. Zolpidem modified-release objectively and subjectively improves sleep maintenance and retains the characteristics of standard zolpidem on sleep initiation and duration in elderly patients with primary insomnia. Sleep. 2005;28(suppl):A244. Abstract 0725. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth T, Soubrane C, Titeux L, Walsh JK. Efficacy and safety of zolpidem MR: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erman M, Krystal A, Zammit G, Soubrane C, Roth T. Zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg, taken for 24 weeks “as needed” up to 7 nights/week, improves subjective measures of therapeutic global impression, sleep onset, and sleep maintenance in patients with chronic insomnia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(suppl 1):S256. Abstract P03.106. [Google Scholar]