Abstract

Much litigation in the United Kingdom and elsewhere could be avoided if doctors correctly assessed the capacity of a person to make a will. An old age psychiatrist and a solicitor explain how to assess capacity using legal tests

Dementia and personal wealth are both increasing. This has led to more wills being contested after a testator's death. Solicitors often adhere to the “golden rule” by asking doctors to certify testamentary capacity (capacity for making a will) in potential testators. We discuss possible pitfalls in this situation and offer advice on how to proceed.

The problem

The policies of former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher led to an increase in property ownership in the UK. Given the steep rise in house prices in Britain since she left office, more people now have substantial estates to bequeath. Alongside this trend has been an increase in the proportion of older people in the population, resulting in a growth in the prevalence of dementia. Dementia and will making are awkward bedfellows. This would scarcely be a problem if people were to make wills before reaching old age, but this often does not happen, and a growing number of wills are challenged after the testator's death. Much litigation could be avoided, however, if doctors, when asked by solicitors, assessed testamentary capacity correctly.

Defining testamentary capacity

The most important fact about capacity is that it is task specific. Incapacity to manage one's financial affairs does not necessarily imply, for example, incapacity to donate power of attorney. The leading authority on testamentary capacity is the judgment in the case of Banks v Goodfellow.1 This judgment remains the test in most common law jurisdictions today and is stated thus:

“It is essential . . . that a testator [1] shall understand the nature of the act [of making a will] and its effects; [2] shall understand the extent of the property of which he is disposing; [3] shall be able to comprehend and appreciate the claims to which he ought to give effect; and, with a view to the latter object, [and] [4] that no disorder of the mind shall poison his affections, pervert his sense of right, or prevent the exercise of his natural faculties; that no insane delusion shall influence his will in disposing of his property and bring about a disposal of it which, if the mind had been sound, would not have been made” (see summary in box 1).

Box 1: The tests for testamentary capacity1

What the testator must be capable of understanding

• The nature and effect of making a will

• The extent of his or her estate

• The claims of those who might expect to benefit from the testator's will (both those being included in, and being excluded from, the will)

What the testator should not have

• A mental illness that influences the testator to make bequests (dispositions) in the will that he or she would not otherwise have included

In the recent case Sharp v Adam and others2 involving a paralysed testator unable to speak because of multiple sclerosis, the judge suggested that there was also a need for sufficient understanding on the part of the testator to arrive at a “rational, fair, and just” will. The testator had disinherited his daughters (in favour of the managers of his stud farm) for no apparent good reason. The Court of Appeal upheld the judge's decision to declare the will invalid but made it clear that the judge's particular interpretation of the Banks v Goodfellow test (see above) had not altered the fundamental validity of that test.

The requirement to know the extent of one's estate does not mean knowing its value down to the last penny. Furthermore, evidence is not necessarily required of a testator's actual understanding, but rather of a capacity to understand these matters. Legally, capacity can be acquired via suitable explanation.

Understanding the moral claims of those whom the testator might be expected to consider in his or her will often leads to trouble. English law—unlike French law, for example—permits testators to leave their wealth (subject to statutory safeguards for dependants) to whoever they please (even to the extent of being capricious) provided that they satisfy the Banks v Goodfellow test. So a man may leave his fortune to his mistress or to the cats' home, but (in a case from our experience) a millionaire with early dementia who disinherited his two sons in favour of his mistress (believing that they had deceived him of large amounts of money) did not fulfil the third part of the Banks v Goodfellow test because he had mistaken his two sons for his nephews.

Delusions do not necessarily invalidate a will unless they influence the testator in making a particular disposition. For example, if a psychotic man makes a will leaving everything to his spouse believing that he will be hanged for tax evasion, his will would probably be considered valid because the delusions did not influence the disposition of his estate. On the other hand, if he left everything to Russia's President Vladimir Putin in the belief that he would escape poisoning by polonium-210, his will would probably be declared invalid.

The golden rule

In a judgment in the case of Kenward v Adams,3 Mr Justice (later Lord) Templeman stated:

“In the case of an aged testator or a testator who has suffered a serious illness, there is one golden rule which should always be observed, however straightforward matters may appear, and however difficult or tactless it may be to suggest that precautions be taken: [the rule is that] the making of a will by such a testator ought to be witnessed or approved by a medical practitioner who satisfies himself of the capacity and understanding of the testator, and records and preserves his examination and finding.”

Mr Justice Templeman's golden rule is very important but is associated with potential pitfalls. Firstly, although the rule implies that the doctor should make an examination, we have found that some doctors are reluctant to get involved or do more than write a letter based on their knowledge of the patient (that is, without attention to the specific legal tests).

Secondly, solicitors sometimes ask general practitioners to witness a will without advising them of the legal tests. As a result, we have encountered practitioners who have done a mini-mental state examination4 and certified capacity on that basis. However, someone with a low score in that test, say 15/30, may have capacity to make a simple will leaving his entire estate to his spouse but be incapable of a more complex will dividing up his estate between several beneficiaries.5 Similarly, someone who scores 27/30 may lack capacity because of impaired judgment and reasoning due to frontal lobe impairment, which is not tested by the mini-mental state examination.

Thirdly, adherence to the golden rule does not guarantee the validity of a will; it merely provides strong evidence in the event of a future challenge. For example, in the Sharp v Adam case mentioned above, the golden rule was meticulously observed by a general practitioner, but the court none the less declared the will invalid. Thus, in a modern context, solicitors and doctors should consider the golden rule as best practice in providing high quality evidence in the event of a legal challenge—a point made by His Honour Judge Alastair Norris QC along with an interesting suggestion that medical assessments might in future be videotaped. 6

How to avoid embarrassment

Box 2 outlines some guidelines for doctors who are asked by a solicitor to assess testamentary capacity. Firstly, insist on a letter of instruction from the solicitor confirming that the patient has consented to examination and disclosure of the results. The solicitor should also provide the doctor at the outset with verifiable information about, for example, the patient's estate and family and confirm in writing the legal test for capacity. (After all, the assessment is for legal not therapeutic reasons.) A reminder from the solicitor that the standard of proof in civil legal matters is the “balance of probabilities” (rather than “beyond reasonable doubt”) is helpful.

Box 2 Process for assessing testamentary capacity

• Get a letter from the solicitor detailing legal tests

• Set aside enough time

• Assess (in the standard way) whether the patient has dementia

• Check that the patient understands each of the Banks v Goodfellow points (box 1)

• Record the patient's answers verbatim

• Check facts, such as the extent of the estate, with the solicitor

• Ask about and review previous wills

• Ask why potential beneficiaries are included or excluded

• If in doubt about capacity, seek second opinion from an old age psychiatrist or other experienced professional

Secondly, allow enough time for assessment. The standard, seven minute consultation is wholly inadequate. Thirdly, have the legal tests to hand—such as a copy of box 1. If, as is usual, the problem is one of possible dementia, take a history and examine the patient's cognitive state (this might well include administering the mini-mental state examination). A full record of the history and examination taken at the time adds force to the doctor's conclusions. After this, go through the specific tests (box 1) systematically and record the answers verbatim. Contemporaneous notes are powerful evidence to put before a court.

You will probably have to explain to your patient why you are asking embarrassing questions, but embarrassment is best not deferred to the witness box, after the patient's death. If not already provided, factual information—such as detail about the estate—should be cross checked with the solicitor. Third party information may be considered, but care should be taken with potential beneficiaries. The examination should be conducted in the absence of anyone who stands to benefit or might exert influence.

Witnessing (in accordance with the strict requirements of the Wills Act 1837) is an essential part of the process, but it authenticates only the testator's signature, not his or her competence. The doctor does not, therefore, have to act as witness, but a doctor's signature doubtless carries the implication that the testator had capacity. Conversely, it is extremely unwise for a doctor to witness a will without having properly assessed the testator's capacity.

Because most trouble arises from disappointed potential beneficiaries, a doctor must ask whether the testator has ever made a will before and who is now going to be excluded and why. A person with dementia may not recall having made a previous will, so this must be checked with the solicitor. Some people make serial wills over their last years of life, so the doctor is wise to check the pattern of will making and review all previous wills. This process can expose impairments of memory, reasoning, judgment, and even delusions. Particular care is needed if close relatives such as children are to be excluded; the reasons should be explored in detail and meticulously recorded.

Deciding whether reasons for excluding offspring result from dementia or personality factors can sometimes be very difficult. In an example from our experience, an elderly dementing woman with a longstanding dependent and demanding personality, excluded her only daughter because she alleged that the latter was neglecting her. The general practitioner took the view that this attitude towards her daughter was a manifestation of the premorbid personality of his patient, whom he knew well. A psychiatrist who reviewed the papers only after she died considered that dementia had caused her to disinherit her daughter, which she would not otherwise have done. We cannot know who was correct, but some general practitioners may feel that assessment of testamentary capacity is beyond their expertise and may ask the solicitor to seek the opinion of a specialist. However, there is no reason why they should not assess testamentary capacity provided they are aware of the legal tests.

The parties in this case reached a compromise settlement before it came to court. Emotions and costs can run high in family battles. For example, the case earlier this year involving the widow of Richard Cox-Johnson, former banker of the Rolling Stones, was settled in mid-trial with estimated legal costs of £300 000 (€443 000; $596 000). Ultimately, capacity is a question of fact, which the court must decide on the evidence as a whole. It is not a matter that a doctor can simply certify one way or another, but the evidence of a properly briefed doctor can greatly assist. We hope that fewer cases would get to the stage of litigation if the golden rule is observed in full measure and correct assessments of testamentary capacity are made and recorded at the time of making a will.

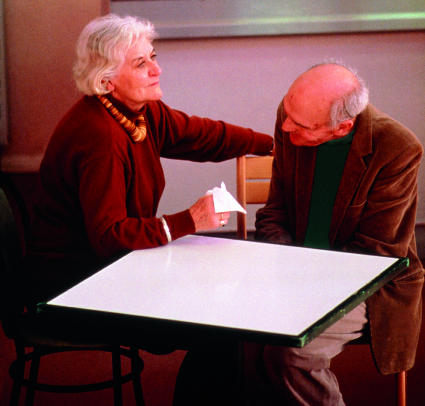

Dementia presents a challenge to doctors to assess correctly a person's capacity to make a will

Summary points

• Increases in longevity, dementia, and personal wealth are leading to more contested wills

• More doctors are being asked to certify testamentary capacity of potential testators

• Doctors need to know the legal tests for testamentary capacity

• Examination based on the legal tests is more likely to avoid future litigation

Contributors: RJ had the idea for the paper and wrote the first draft, on which PS made comments and suggestions that were all incorporated. Both authors helped to amend the paper in the light of the referees' comments. RJ is the guarantor.

Competing interests: RJ writes expert reports for solicitors in contentious probate cases. PS is a solicitor specialising in acting for beneficiaries in contentious probate cases.

Provenance and peer review: Non-commissioned; peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Banks v Goodfellow [1870] 5 LR QB 549

- 2.Sharp & Bryson v Adam and Others [2006] WTLR 1059

- 3.Kenward v Adams (1975) Times 29 Nov

- 4.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the mental state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatry Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shulman KI, Cohen CA, Hull I. Psychiatric issues in retrospective challenges of testamentary capacity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:63-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris A. An article overtaken by a decision by His Honour Judge Alastair Norris QC. Newsletter of the Association of Contentious Trust and Probate Specialists (ACTAPS) 2007;87:1-6. [Google Scholar]