Abstract

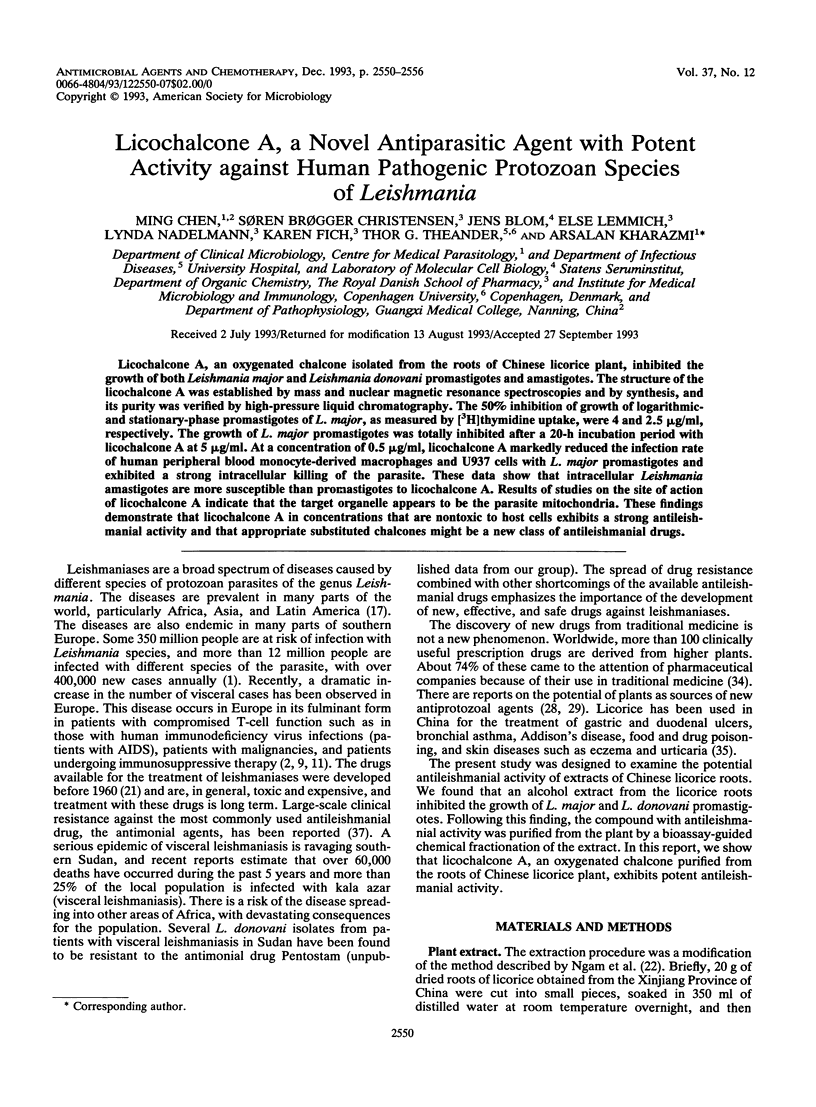

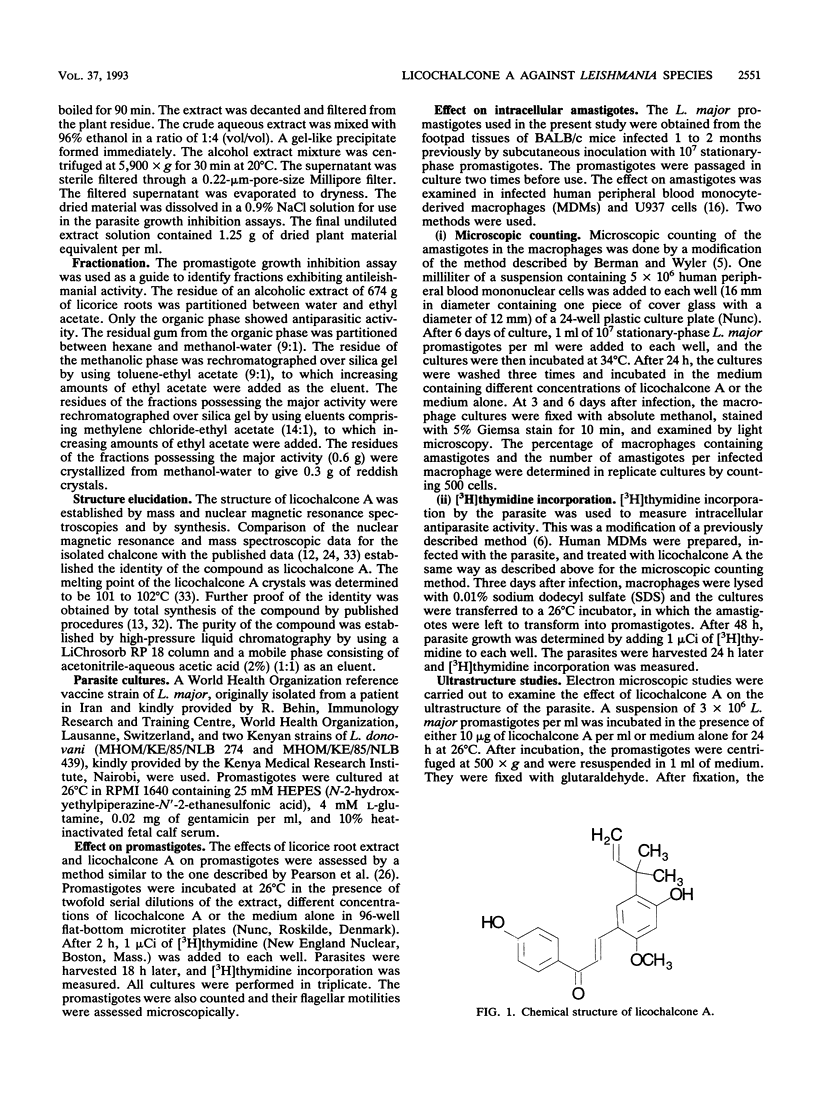

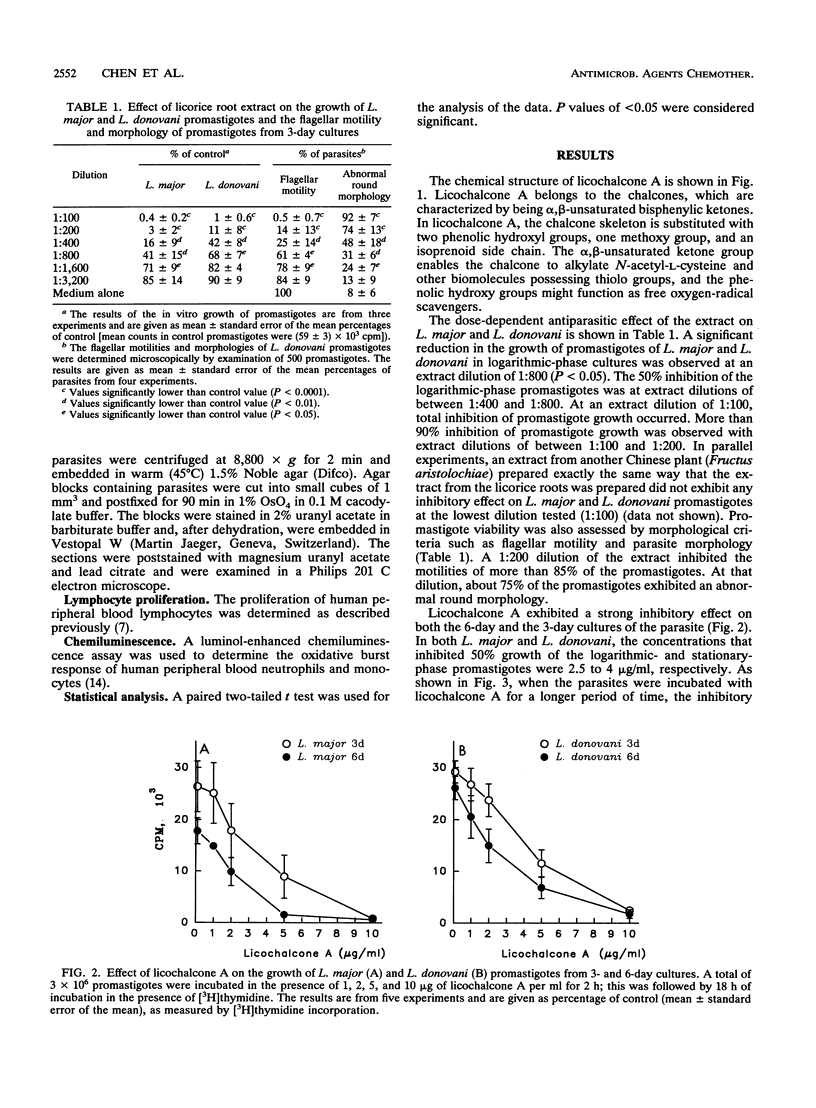

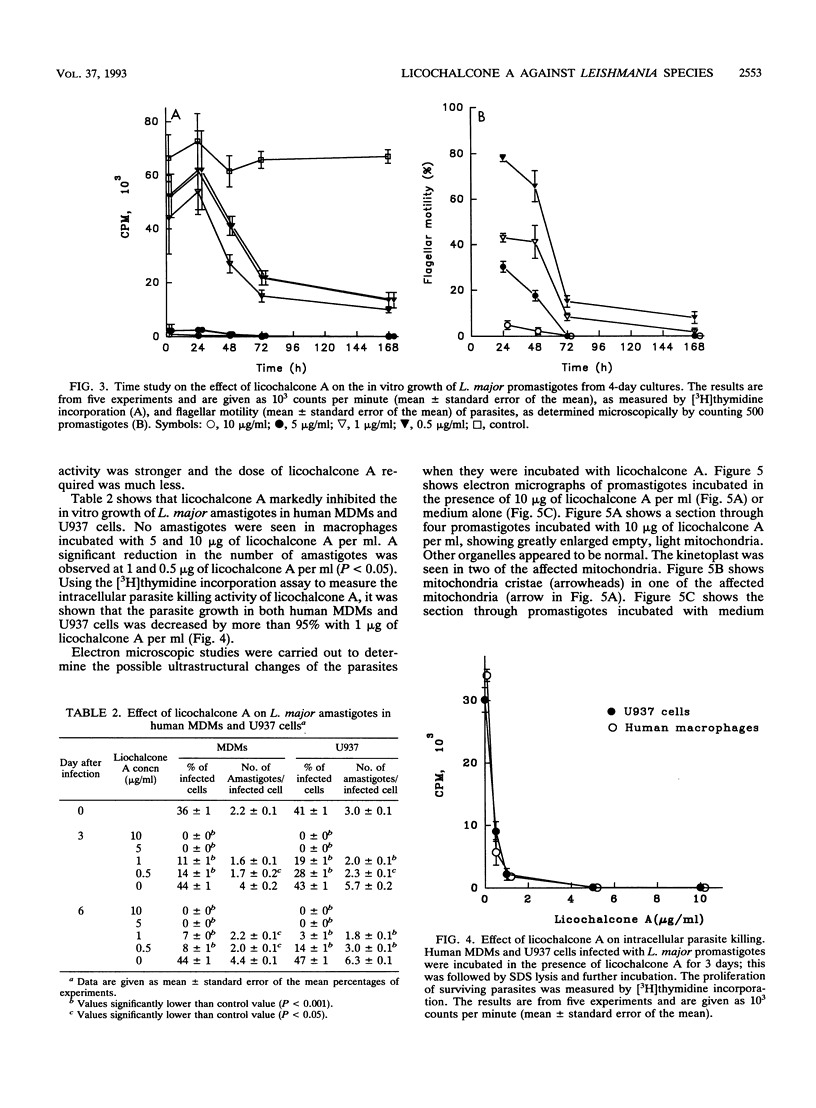

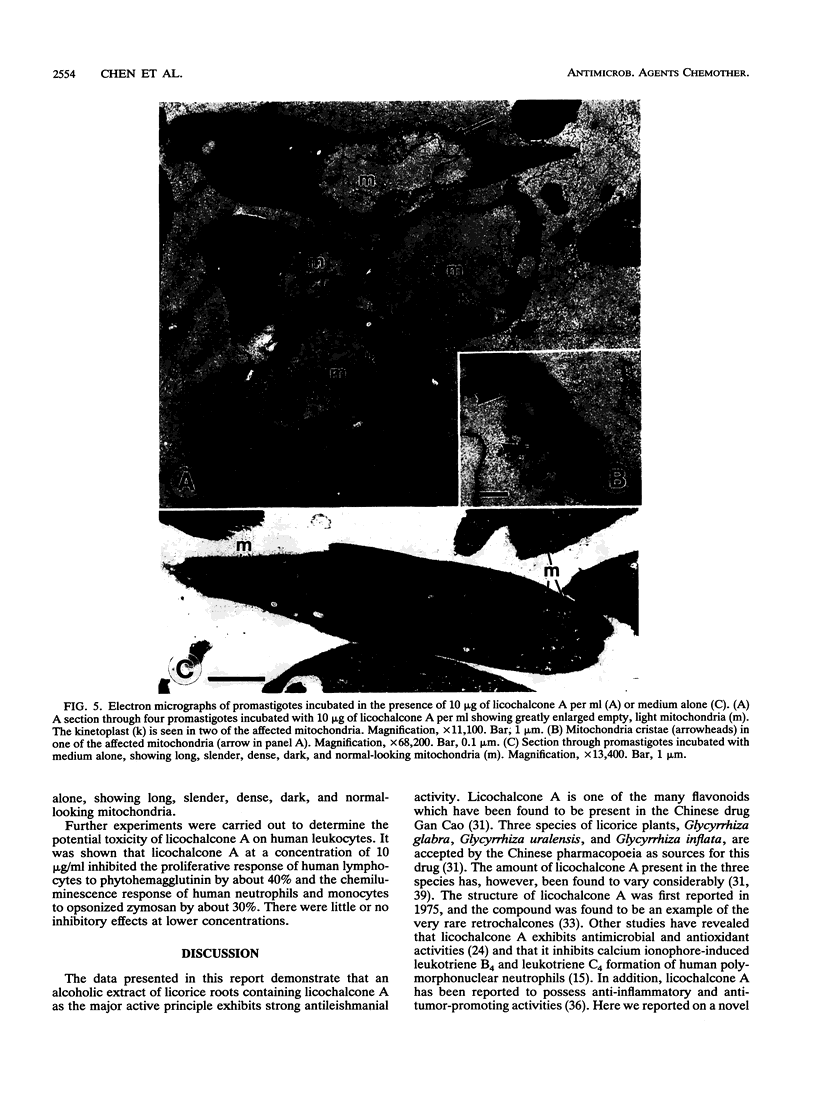

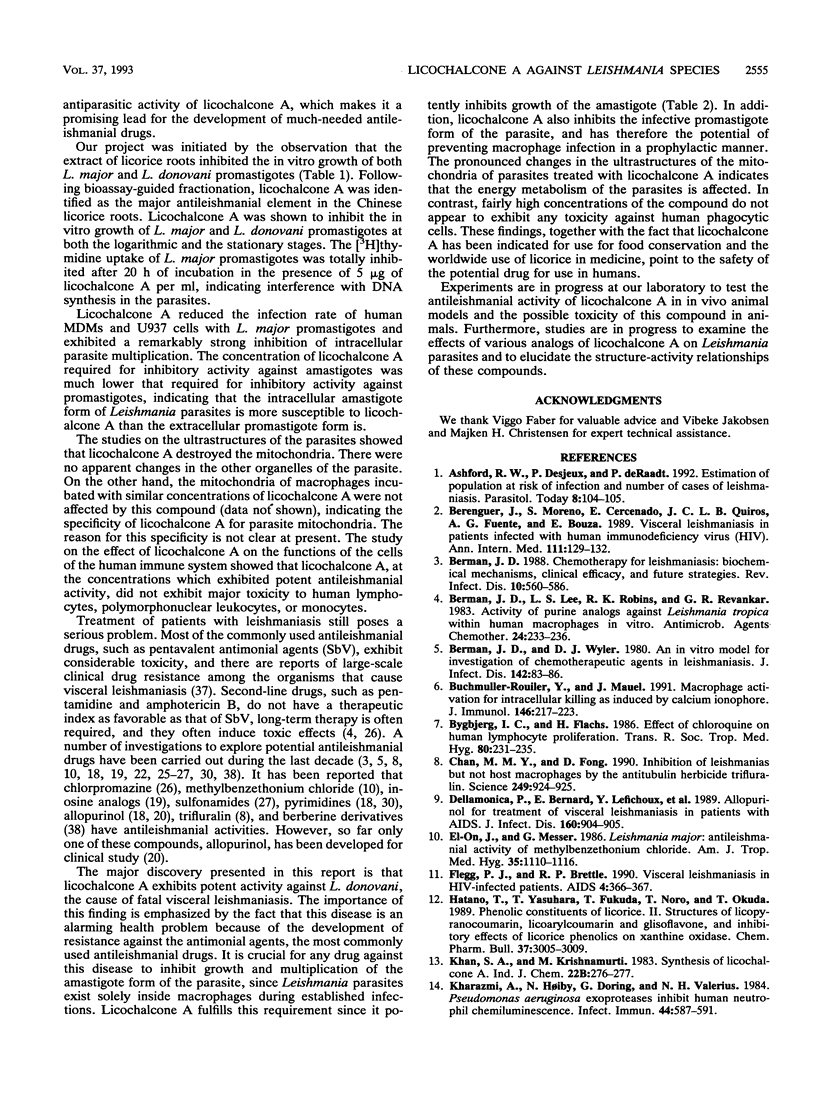

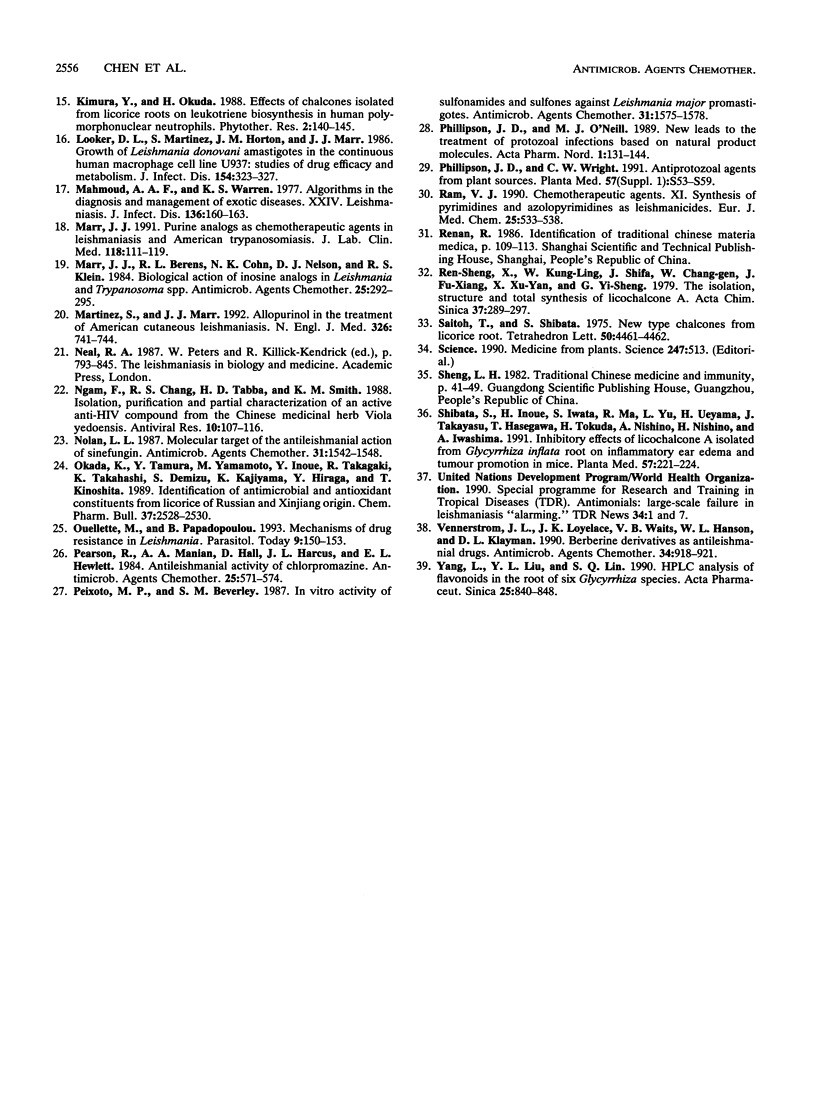

Licochalcone A, an oxygenated chalcone isolated from the roots of Chinese licorice plant, inhibited the growth of both Leishmania major and Leishmania donovani promastigotes and amastigotes. The structure of the licochalcone A was established by mass and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopies and by synthesis, and its purity was verified by high-pressure liquid chromatography. The 50% inhibition of growth of logarithmic- and stationary-phase promastigotes of L. major, as measured by [3H]thymidine uptake, were 4 and 2.5 micrograms/ml, respectively. The growth of L. major promastigotes was totally inhibited after a 20-h incubation period with licochalcone A at 5 micrograms/ml. At a concentration of 0.5 microgram/ml, licochalcone A markedly reduced the infection rate of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages and U937 cells with L. major promastigotes and exhibited a strong intracellular killing of the parasite. These data show that intracellular Leishmania amastigotes are more susceptible than promastigotes to licochalcone A. Results of studies on the site of action of licochalcone A indicate that the target organelle appears to be the parasite mitochondria. These findings demonstrate that licochalcone A in concentrations that are nontoxic to host cells exhibits a strong antileishmanial activity and that appropriate substituted chalcones might be a new class of antileishmanial drugs.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ashford R. W., Desjeux P., Deraadt P. Estimation of population at risk of infection and number of cases of Leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1992 Mar;8(3):104–105. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer J., Moreno S., Cercenado E., Bernaldo de Quirós J. C., García de la Fuente A., Bouza E. Visceral leishmaniasis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Ann Intern Med. 1989 Jul 15;111(2):129–132. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-2-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J. D. Chemotherapy for leishmaniasis: biochemical mechanisms, clinical efficacy, and future strategies. Rev Infect Dis. 1988 May-Jun;10(3):560–586. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J. D., Lee L. S., Robins R. K., Revankar G. R. Activity of purine analogs against Leishmania tropica within human macrophages in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Aug;24(2):233–236. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J. D., Wyler D. J. An in vitro model for investigation of chemotherapeutic agents in leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1980 Jul;142(1):83–86. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmüller-Rouiller Y., Mauël J. Macrophage activation for intracellular killing as induced by calcium ionophore. Correlation with biologic and biochemical events. J Immunol. 1991 Jan 1;146(1):217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygbjerg I. C., Flachs H. Effect of chloroquine on human lymphocyte proliferation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80(2):231–235. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. M., Fong D. Inhibition of leishmanias but not host macrophages by the antitubulin herbicide trifluralin. Science. 1990 Aug 24;249(4971):924–926. doi: 10.1126/science.2392684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellamonica P., Bernard E., Le Fichoux Y., Politano S., Carles M., Durand J., Mondain V. Allopurinol for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1989 Nov;160(5):904–905. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-On J., Messer G. Leishmania major: antileishmanial activity of methylbenzethonium chloride. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986 Nov;35(6):1110–1116. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegg P. J., Brettle R. P. Visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1990 Apr;4(4):366–367. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T., Yasuhara T., Fukuda T., Noro T., Okuda T. Phenolic constituents of licorice. II. Structures of licopyranocoumarin, licoarylcoumarin and glisoflavone, and inhibitory effects of licorice phenolics on xanthine oxidase. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1989 Nov;37(11):3005–3009. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi A., Høiby N., Döring G., Valerius N. H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproteases inhibit human neutrophil chemiluminescence. Infect Immun. 1984 Jun;44(3):587–591. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.587-591.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker D. L., Martinez S., Horton J. M., Marr J. J. Growth of Leishmania donovani amastigotes in the continuous human macrophage cell line U937: studies of drug efficacy and metabolism. J Infect Dis. 1986 Aug;154(2):323–327. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A., Warren K. S. Algorithms in the diagnosis and management of exotic diseases. XXIV. Leishmaniases. J Infect Dis. 1977 Jul;136(1):160–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr J. J., Berens R. L., Cohn N. K., Nelson D. J., Klein R. S. Biological action of inosine analogs in Leishmania and Trypanosoma spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Feb;25(2):292–295. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr J. J. Purine analogs as chemotherapeutic agents in leishmaniasis and American trypanosomiasis. J Lab Clin Med. 1991 Aug;118(2):111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez S., Marr J. J. Allopurinol in the treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. N Engl J Med. 1992 Mar 12;326(11):741–744. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203123261105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan F., Chang R. S., Tabba H. D., Smith K. M. Isolation, purification and partial characterization of an active anti-HIV compound from the Chinese medicinal herb viola yedoensis. Antiviral Res. 1988 Nov;10(1-3):107–116. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(88)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan L. L. Molecular target of the antileishmanial action of sinefungin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Oct;31(10):1542–1548. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K., Tamura Y., Yamamoto M., Inoue Y., Takagaki R., Takahashi K., Demizu S., Kajiyama K., Hiraga Y., Kinoshita T. Identification of antimicrobial and antioxidant constituents from licorice of Russian and Xinjiang origin. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1989 Sep;37(9):2528–2530. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette M., Papadopoulou B. Mechanisms of drug resistance in Leishmania. Parasitol Today. 1993 May;9(5):150–153. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. D., Manian A. A., Hall D., Harcus J. L., Hewlett E. L. Antileishmanial activity of chlorpromazine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 May;25(5):571–574. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto M. P., Beverley S. M. In vitro activity of sulfonamides and sulfones against Leishmania major promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Oct;31(10):1575–1578. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.10.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson J. D., Wright C. W. Antiprotozoal agents from plant sources. Planta Med. 1991 Oct;57(7):S53–S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S., Inoue H., Iwata S., Ma R. D., Yu L. J., Ueyama H., Takayasu J., Hasegawa T., Tokuda H., Nishino A. Inhibitory effects of licochalcone A isolated from Glycyrrhiza inflata root on inflammatory ear edema and tumour promotion in mice. Planta Med. 1991 Jun;57(3):221–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennerstrom J. L., Lovelace J. K., Waits V. B., Hanson W. L., Klayman D. L. Berberine derivatives as antileishmanial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 May;34(5):918–921. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Liu Y. L., Lin S. Q. [HPLC analysis of flavonoids in the root of six Glycyrrhiza species]. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1990;25(11):840–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]