Abstract

This review intends to provide examples how comparative and genetic analyses both contribute to our understanding of the rules for cortical development and evolution. Genetic studies helped to understand evolutionary rules of telencephalic organization in vertebrates. The control of the establishment of conserved telencephalic subdivisions and the formation of boundaries between these subdivisions has been examined and revealed the very specific alterations at the striatocortical junction. Comparative studies and genetic analyses both demonstrated the differential origin and migratory pattern of the two basic neuron types of the cerebral cortex. GABAergic interneurons are mostly generated in the subpallium and a common mechanisms govern their migration to the dorsal cortex in both mammals and sauropsids. The pyramidal neurons are generated within the cortical germinal zone and migrate radially. The earliest generated cell layers comprising preplate cells. Reelin positive Cajal-Retzius cells are a general feature of all vertebrates studied so far, however, there is a considerable amplification of the reelin signaling, which might have contributed to the establishment of the basic mammalian pattern of cortical development. Based on numerous recent observations we shall present an argument that specialization of the mitotic compartments might constitute a major drive behind the evolution of the mammalian cortex. Comparative developmental studies revealed distinct features in the early compartments of the developing macaque brain drawing our attention to the limitations of some of the current model systems for understanding human developmental abnormalities of the cortex. Comparative and genetic aspects of cortical development both reveal the workings of evolution.

Keywords: Animals; Cell Differentiation; genetics; physiology; Cerebral Cortex; cytology; embryology; growth & development; Evolution; Humans; Models, Neurological; Neurons; physiology

Keywords: neurogenesis, neuronal migration, Cajal-Retzius Cells

Owing to the advances made in the development of mouse genetics, mouse became the favoured model system for the basic understanding of cortical development (Goffinet and Rakic, 2000). Gene functions implicated in human brain developmental abnormalities (including childhood epilepsy, schizophrenia, autism and attention deficit disorder, see Francis et al., in this issue) are currently being analysed in various transgenic mouse models. These models have proved to be invaluable in the understanding of mammalian cortical development, but there are also numerous limitations. For specific questions regarding cortical development, carnivores and primates are the preferred model organisms, and for many aspects of human developmental disorders there are no appropriate animal models (yet). And it is imperative that the differences between model organisms and humans are fully taken into account when conducting gene function analyses.

The last decade brought important progress in the understanding of various developmental steps in mammalian cerebral cortical development and has left us with an increased need for comparative analysis of these programs. The cellular and molecular mechanism of radial migration of neurons within the cortex and tangential migration of GABAergic neurons from the subpallium has been established in both mammals (mouse, rat, carnivores, primate) and sauropsids and some of the guidance mechanisms have been elucidated (Métin et al., in this issue). Formation of the first cortical layers and the distribution and origin of the first postmitotic cells is much better understood both in mammals and other vertebrates (e.g. Bielle et al., 2005). New distinct compartments of neurogenesis have been identified in the developing mammalian cerebral cortex, and it is hypothesized that these compartments contribute different cell populations (Noctor et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Guillemot et al., this issue). Finally, cell cycle parameters have been documented in the mouse and primate germinal zones (Smart et al., 2002; Lukaszewicz, 2005). By comparing brain development in different species we can gain insight into the origin of the mammalian neocortex, and into the evolutionary changes that might have occurred.

Comparative developmental analysis can provide insight into brain evolution

There are great variations from the basic pattern of forebrain organization in different vertebrates (Figure 1). While many of these forebrain structures can be related to each other unambiguously, others have been cryptic (Northcutt and Kaas, 1995; Karten, 1997; Striedter, 1997; Molnár and Butler, 2002a,b). We are still left with numerous unanswered questions: What aspects of development had to change to produce a multilayered cortex and subsequently to produce a larger cortex? What aspects of cell proliferation, polarity of construction of the cortical plate or cell migration and differentiation along the pallial-subpallial boundary had to be reconfigured during evolution to arrive at the developmental mechanisms used by primates today? Recent comparative gene expression studies together with detailed comparative analysis of forebrain development try to provide insight into the evolutionary changes that might have occurred.

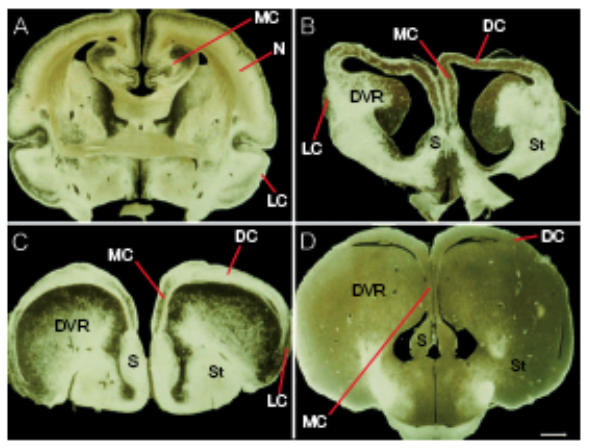

Figure 1.

Fibre stained coronal sections of four different amniote brains viewed under dark field illumination to demonstrate the spectacular differences between forebrain organization in A: marsupial, Native Cat, Dysaurus hallucatus, B: Turtle, Pseudemus scripta elegans, C: Iguana, Iguana iguana, D: Crocodile (Australian). Note the thicker dorsal cortex in marsupial (A) and the huge ball-like structure in B-D protruding into the lateral ventricle. Abbreviations: ST, striatum; MC, medial cortex; LC, lateral cortex; S, septum; DVR, dorsal ventricular ridge. Scale bar: 1mm. (Modified from Molnár and Butler, 2002b, reproduced with the permission of Elsevier Science B.V.).

In this review we shall first give an overview on the telencephalic organization in vertebrates; genetic control of the establishment of conserved forebrain subdivisions and the formation of boundaries between these developmental compartments with particular attention to the striatocortical junction. This is the region where the major differences occur in mammals and sauropsids. We shall give examples where genetic studies on the vertebrate forebrain helped to understand evolutionary rules. Second we shall review the differential origin of pyramidal and non-pyramidal cortical neurons. Comparative studies and genetic analyses show that the dual origin of these two basic neuron types is a very general feature of the cortical organization across all vertebrates studied so far. GABAergic interneurons have a common origin in the subpallium and a common mechanisms govern their migration. Third, we shall make comparisons among the early generated cell layers comprising preplate cells, then forth the germinal zones. Based on numerous recent observations we shall present an argument that the elaboration of mitotic compartments might have been the drive behind mammalian cortical evolution. Fifth, we shall compare cell cycle parameters in the dorsal cortex. Unfortunately we shall have to restrict this comparison to mammals, because no such data is available on other vertebrates. We shall not discuss comparative aspects of early cell death, although we realize that this is a very interesting aspect of cortical development (Rakic, 2005). The developmental (Mallamaci and Stoykova, in this issue) and evolutionary aspects of cortical regionalization (Krubitzer and Khan, 2003) are extremely exciting issues, but they could not be given justice here and we refer the reader to recent reviews of this issue (Grove and Fukuchi-Shimogori, 2003; Guillery, 2005; Krubitzer and Kaas, 2005). We shall finish with the review of relevant human cortical developmental disorders and point out the limitations of some of our model systems. Much of our recent understanding of cortical development comes from studies on the mouse, and work on primate cortical development has been carried out in only a handful of laboratories around the world. Despite the small quantity of work on the primate, it does reveal a number of unique primate features that are significant in terms of general evolutionary trends in cortical development and crucial for understanding development of the human cortex. We believe that by stressing the differences in nonmammalian vertebrates and the differences within mammals we can generate more thought and debate on these important issues.

Telencaphalic organization in vertebrates; differences at the striatocortical junction between mammals and reptiles

Gene expression and function studies in mouse and chick provide evidence for a common organization of the developing telencephalon in vertebrates (Smith-Fernandez et al., 1998; Puelles et al., 2000). Based on the conserved expression of homeobox-containing and other transription factors it has been proposed that the pallium consists of four subdivisions: the medial (MP), the dorsal (DP), the lateral (LP) and the ventral (VP) pallium that contain the anlagen of the hippocampus, isocortex, olfactory cortex/part of amygdala and claustrum/amygdalar complex, respectively (Puelles et al., 2000). The subpallium contains four subdivisions: the lateral ganglionic eminence, subdivided into dorsal and ventral part, dLGE, vLGE, respectively, the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), the caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), and the septum contributing to the generation of striatum, pallidum and the telencephalic stalk, respectively (reviewed by Marín and Rubenstein, 2001).

Results from gene expression analyses have led to the recognition that the domain of the ventral pallium actually extends over the lateral most territory of the LGE where it abuts upon the domain of the dLGE, outlining thereby the pallial/subpallial border (PSPB). As early as stage E9.0 the PSPB is delineated by the homeodomain containing transcription factors Pax6 and Gsh2, that are expressed in the progenitors of the pallium and subpallium, respectively (Walther and Gruss, 1991; Torreson et al., 2000, Yun et al., 2001). The VP progenitors express at a very high level both Pax6 (Stoykova et al., 1996, 1997) and its direct target gene Ngn1/2 (Scardigli et al., 2003). A recent study provides evidence that at early developmental stages, non-overlapping or only partially overlapping streams of cells with distinct molecular expression profiles emerge form the VP/LP domains, migrate towards the basal telencephalon and contribute to the formation of different nuclei of the amygdalar complex (Tole et al., 2005). In the Small eye mutant where Pax6 is not functional (Hill et al., 1991), the expression of the VP markers Dbx2 and sFrp2 (Kim et al., 2001; Yun et al., 2001; Assimacopoulos et al., 2003) is abolished. Furthermore, the progenitors of the VP/LP do not express pallial markers, but instead take on subpallial characteristics (Stoykova et al., 1996; 2000; Toresson et al., 2000; Yun et al., 2001) determined by the expression of subpallial marker genes (Kroll and O’Leary, 2005). The high expression level of Pax6 in the VP progenitors appears to be necessary for the specification of the nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract and the lateral, basolateral and basomedial nuclei of the amygdala that fail to form in the Small eye mutant (Tole et al., 2005), and ventral pallium has further severe abnormalities in the Pax6/lacZ knockout mouse (Jones et al., 2002).

Judged by the absence of Emx1 expression in the progenitors of the ventral pallium and the abundant expression of Tbr1 in the mantle zone in mouse and chick, it has been proposed that the avian nidopallium (Reiner et al., 2004; previously called neostriatum) corresponds to the VP domain in the mouse (Puelles et al., 2000). Chicken genes homologous to Pax6, Dlx2 and Emx1 are expressed in a topologically similar pattern, suggesting that the avian “paleostriatum” corresponds to part of the mouse subpallium (Puelles et al., 2000). The developmental programme of the pallial-subpallial boundary might have undergone some important reorganizations during evolution (Butler and Molnár, 2002; Molnár and Butler, 2002a,b), which resulted in the rearrangements of several structures and opened up the path for further cortical development. There are numerous hypotheses on the possible evolutionary changes that led to the transformation of ventral pallium in mammals (Striedter 1997; 2005; see Fig. 2). Further work on gene expression patterns with special attention to genes shared by critical structures (lateral cortex, claustrum, lateral amygdala and endopyriform cotex) could eventually resolve these challenging questions (Arimatsu, 1994; Wang and Molnár, 2005; Figure 3). As our understanding of genetics and comparative aspects of development progresses new hypotheses emerge.

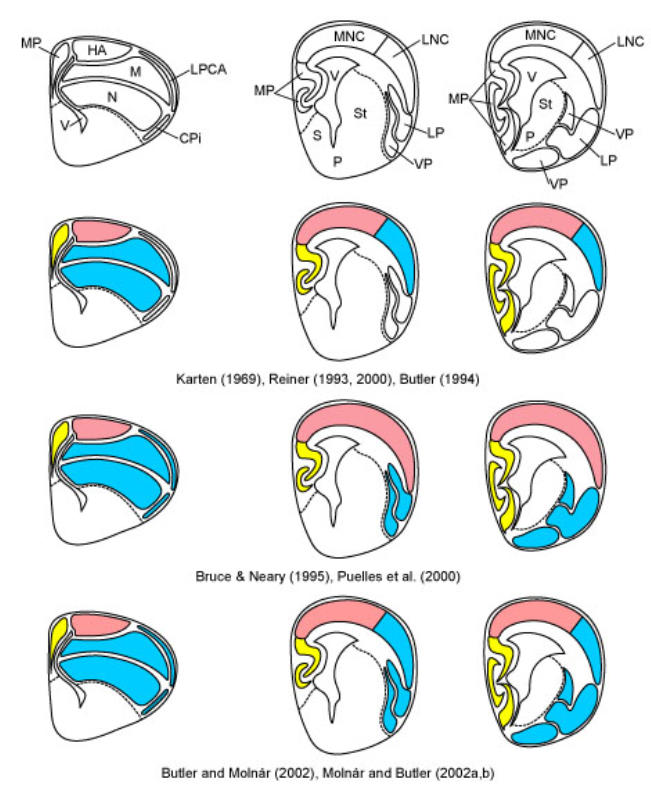

Figure 2.

Overview of three current theories on the evolution f the dorsal pallium in amniotes. In each row, a drawing of a transverse hemisection through the telencephalon of a developing bird is shown to the left, and two drawings of transverse hemisections through the telencephalon of a developing mammal are shown to the right, with the far right drawing being the more caudal one and through the level of the amygdala. In the top row, the structures are identified (see abbreviations below). The second row illustrates the ADVR-lateral neocortex hypothesis of Reiner (1993) and Butler (1994), derived from the equivalent cell hypothesis of Karten (1969). The third row illustrates the ADVR-claustroamygdalar hypothesis, variations of which are supported by Bruce and Neary (1995), Stredter (1997), Puelles and co-workers (Puelles et al., 2000; 2007; Medina et al., 2005a,b), and Martínez-Garcia et al., (2002;. The fourth row illustrate the ADVR-lateral neocortex plus claustroamygdalar field homology hypothesis of Butler and Molnár (2002). The colors and fill patterns are used to indicate comparative structures for each hypothesis. Since the piriform cortex is not shown as a separate entitiy in the mammalian figures but rather is included in the LP/VP regions, it is not colored in most cases. All of these hypotheses basically agree on a discrete homology of most or all of piriform cortex across amniotes. Abbreviations: Cpi, Piriform cortex; HA, Hyperpallium apicale; LP, Lateral pallium; LNC, Lateral neocortex (i.e., collothalamic-recipient neocortex); LPCA, Lateral pallial cortical area; M, Mesopallium; MNC, Medial neocortex (i.e., lemnothalamic-recipient neocortex); MP, Medial pallium; N, Nidopallium; P, Pallidum; S, Septal nuclei; St, Striatum; V, Lateral ventricle; VP, Ventral pallium. (Modified by A. Butler from Butler and Hodos, 2005)Figure modified and kindly provided by AB Butler and reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

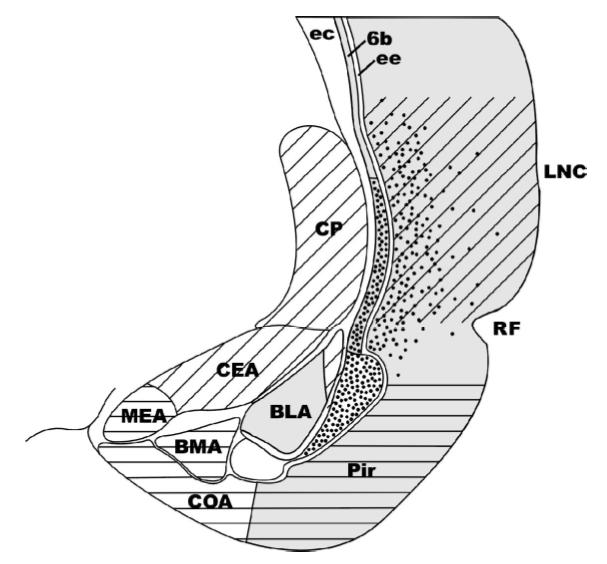

Figure 3.

The schematic diagram illustrates the special relationships among components of the lateral part of the telencephalon of mammals. Overlapping but noncongruent distribution of hodological and gene expression patterns are represented in the lateral part of a coronal section through the right hemisphere of a rat. Dots represent latexin-positive neurons, Emx-1 positive regions in gray shade. Collothalamic inputs indicated by diagonal lines of olfactory inputs by horizontal lines. The claustrum, filled with latexin positive cells and Emx1-positive (Cl). The collothalamic-recipient Lateral Amygdala (LA) lies dorsolaterally adjacent to BLA. Abbreviations: BLA, BMA, CEA; COA, LA, and MEA, basolateral, basomedial, central cortical, lateral, and medial nuclei of the amygdala, respectively; CP, caudate-putamen; ec, external capsule; ee, extreme capsule (as present in most mammals, but not in rat); LNC, lateral neocortex; Pir, piriform cortex; RF, rhinal sulcus; 6b, layer 6b of neocortex. Drawings adapted from Butler and Molnáar (2002).

Differential origin of pyramidal and nonpyramidal cortical neurons

The principal neuronal types of the cerebral cortex are the excitatory pyramidal cells, which project to distant targets, and the inhibitory nonpyramidal cells, which are the cortical interneurons. These two functional classes are both present in the mammalian isocortex and in the dorsal cortex of sauropsids although this last one lacks several cell types found in mammals. Projection neurons and inhibitory interneurons may therefore represent the basic components required to build a functional cortex making it plausible that the two functional types of cells were already present in the common ancestor (Blanton et al., 1987; Reiner, 1991). Pyramidal neurons are generated in the cortical neuroepithelium and migrate radially to reach the cortex following an inside-outside gradient in mammals (Rakic, 1995). In rodent, only a few nonpyramidal cells are generated in the cortical ventricular zone (Parnavelas, 2000). It was recently established that cells of the pallidum also contribute to the formation of the cerebral cortex with interneurons (DeCarlos et al., 1995; Tamamaki et al., 1997; Anderson et al., 1997). These cells migrate tangentially through the striatocortical junction to reach the cortex. Great interest in further comparative studies has been generated by this discovery. Such migratory patterns had been predicted for developing mammals as part of a ‘reptilian-mammalian transformation’ (Karten, 1969; 1998), however comparative studies have revealed the existence of similar tangential migration in sauropsids, restricted to GABAergic neurons (Cobos et al., 2001; Tuorto et al., 2003). It seems that the various transformations at the pallial-subpallial boundaries observed in mammals and sauropsids occur in addition to and largely independently from the tangential migratory streams of the GABAergic neurons (Molnár and Butler, 2002a,b).

The exact origin of the tangentially migrating GABAergic neurons in mammals has been controversial. It is now well established that the vast majority of these cells originate in the medial (MGE) and caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), the primordia of the globus pallidus (Lavdas et al., 1999; Sussel et al., 1999; Wichterle et al., 1999; Nery et al, 02, Yozu et al, 05). Experiments in living whole forebrain slice cultures have shown that these neurons follow long tangential migratory routes to their positions in the developing cortex. The molecular and cellular mechanisms of both migratory pathways have been extensively studied and some links with human pathologies analyzed (See Francis et al., in this issue)

The percentage of GABAergic neurons in avian pallial regions and their relatively uniform distribution closely resembles the pattern seen in other vertebrates, including mammals (Jarvis et al., 2005; Veenman and Reiner, 1994). In birds as in rodents, most GABAergic interneurons originate in the ventral telencephalon (Fig. 4). However, the relative contribution of the pallidum (or medial ganglionic eminence of the telencephalon) and of the paleo-striatum (or lateral ganglionic eminence of the telencephalon) to the GABAergic population is debated (Cobos et al., 2001; Tuorto et al., 2003). In rodents, the GABA phenotype of cortical interneurons differentiates under the control of transcription factors of the Dlx family that are expressed in ventral forebrain territories (Stuhmer et al., 2002). The differentiation of GABAergic neurons is likely to be controlled by the same genetic pathway in distant species such as reptiles, birds and mammals. Indeed, orthologs of Dlx genes have been cloned that define ventral forebrain domains with homologous functions in these three classes (Fernandez et al., 1998; Puelles et al., 2000). In lamprey prolarvae also, GABA immunoreative neuronal populations differentiate initially in the ventral forebrain in a region corresponding topologically to the ganglionic eminence of the mouse embryo (Melendez-Ferro et al., 2002). The predominantly ventral subpallial origin of GABAergic interneurons seems therefore to be a common feature of vertebrate forebrains. However, there are major differences in the proportion of the GABAergic neurons generated locally in the pallium and in the striatum/subpallium (lateral and medial ganglionic eminences) in mouse/rat and primates. In human it has been estimated that 65% of GABAergic neurons are born locally in the cortical germinal zone (Letinic and Rakic, 2001; Fig. 4), whereas in mouse this estimate is only 5% (Letinic et al., 2002; Tan, 2002). Interestingly, in human the dorsal thalamic association nuclei of the diencephalon receive their GABAergic neurons from the ganglionic eminence of the telencephalon (Lecinic and Rakic, 2001). This interneuron migration from telencephalon to diencephalon is believed to be specific to human, although we still lack information on these developmental steps in great apes.

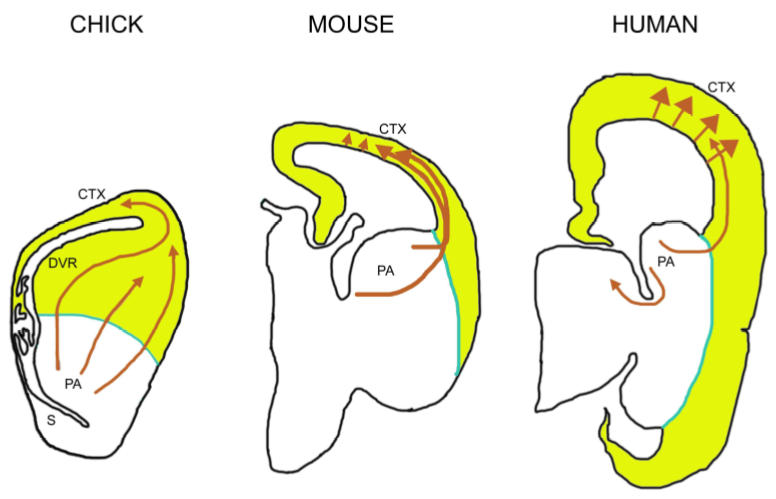

Figure 4.

Common mechanism of subpallial origin and tangential migration of GABAergic neurons in bird, rodent and human. Schematic outlines represent the cross-sections through chick, mouse and human forebrains. Orange arrows depict the migratory patterns of GABAergic neurons from subpallium (sPA). See text for details. Left panel was inspired by Cobos et al., 2001, right panels by Tan (2002).

During embryonic development, GABAergic neurons that originate in the ventral subpallium progressively colonise the dorsal pallium (see Métin et al., this issue). Emx genes are expressed in this dorsal domain which mostly generates excitatory glutamatergic neurons (Anderson et al., 2002; Gorski et al., 2002) and in birds and reptiles it comprises the dorsal ventricular ridge (DVR) (Fernandez et al., 1998; Jarvis et al., 2005; Puelles et al., 2000). In rodents, GABAergic neurons follow well defined migratory routes as observed in organotypic slices (López-Bendito et al., 2004; Nadarajah and Parnavelas, 2002; Nadarajah et al., 2002; see Figure 4). In birds, GABAergic cells follow tangential routes in both the subpallium and pallium and show branched leading processes (Tuorto et al., 2003). Their similarities in morphology to mammalian tangentially migrating interneurones are suggestive of common mechanisms of migration (Bellion et al, 2005). Whether these mechanisms are shared by the other vertebrate species remains to be determined. So far, the sequence of development of GABAergic interneurons in the turtle cortex is suggestive of tangential migration from ventral territories though this remains to be firmly established (Blanton and Kriegstein, 1991).

In mammals, the capacity to migrate tangentially over long distances is maintained for interneurons precursors into maturity. Indeed, interneurones produced in the adult SVZ migrate tangentially toward the olfactory bulb (OB) (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993 and 1994). Neurogenesis has also been described in the wall of the lateral ventricle in adult birds, lizards and turtles. In these classes as in mammals, the GABAergic neurons produced mostly accumulate in the OB, suggesting again conserved mechanisms of tangential migration in distant species in the vertebrate forebrain (Garcia-Verdugo et al., 1989; Perez-Canellas et al., 1997; Perez-Canellas and Garcia-Verdugo, 1996).

Comparisons among first generated cell layers

The germinal zones lining the ventricle generate the pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex. It is well established that newly produced neurons migrate out of the germinal zone according to a strict timetable. In both carnivores and rodents, the first wave of post-mitotic cells generated in the so-called ventricular zone (VZ) form the preplate. The preplate contains early appearing CR cells, GABAergic neurons and pioneer neurons (Meyer et al., 2000). The cortical plate (CP) is formed by subsequently generated neurons that split the preplate into a marginal zone (MZ) and a subplate (Marin-Padilla 1978; Smart and McSherry 1982; Smart and Smart 1982; Luskin and Shatz 1985). The MZ and the cortical plate are destined to become the 6-layered structure of the mature cortex. The pioneer neurons give rise to the ‘presubplate’ beneath the initial CP (Kostovic and Rakic, 1990), which is the forerunner of the subplate, a transient waiting compartment for thalamocortical and corticocortical fibers. The subplate exerts an important control over later stages of cortical development (Allendoerfer and Shatz, 1994; Ghosh and Shatz 1992). The cortical plate layers are formed according to an inside-out neurogenetic gradient, with later generated cohorts bypassing earlier-born neurons to settle at the top of the cortical plate (Angevine and Sidman 1961). Once in position, they detach from the radial glial guide. In consequence, the oldest neurons of the cortex occupy the deep layers, whereas the upper layers are composed of late-born neurons. The concept of preplate partition, proposed on the basis of non-primate data, has led to the idea that the subplate is a derivative of the preplate (Marin-Padilla 1978; Luskin and Shatz, 1985). This constitutes a major departure from early-formed embryonic compartments in both human and non-human primates where a complex succession of transient embryonic layers accompanies the transition from the preplate to the cortical plate (Meyer et al. 2000; Smart et al. 2002; Figure 5 taken from Fig 8 Smart et al., 2002).

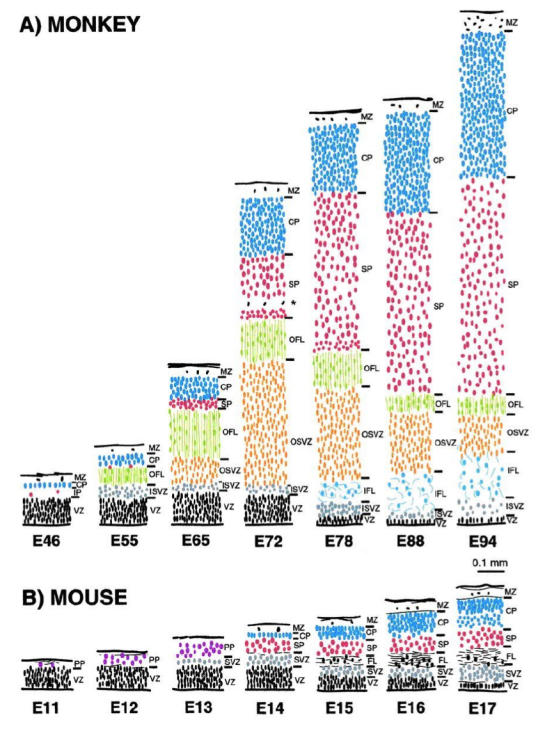

Figure 5.

Comparison of histological sequences in the developing mouse and monkey telencephalic wall. These drawings are of transects through putative Area 17 in (A) monkey and (B) mouse at comparable developmental stages. The depth of each layer is drawn to a common scale. The internal detail of each layer is not to scale but depicts the orientation, shape and relative packing density of nuclei in each layer. The vertically aligned pairs have been chosen with reference to birthdating experiments so as to illustrate corticogenesis at equivalent developmental stages. Abbreviations: cortical plate (CP); inner fibre layer (IFL); inner subventricular zone (ISVZ); marginal zone (MZ); outer fibre layer (OFL); outer subventricular zone (OSVZ); subplate proper (SP); ventricular zone (VZ). Reproduced with permission from Smart et al., (2002).

None the less, there is a prominent subplate in human and non-human primates (Kostovic and Rakic 1990; Smart et al. 2002). In monkeys the majority of subplate cells are born after the onset of cortical plate formation and cells continue to accumulate in this compartment up to mid-corticogenesis at E78 (see Figure 5). This indicates that whereas subplate neuron production is almost terminated by the onset of cortical plate production in rodents, in the monkey, the generation of the subplate and cortical plate is simultaneous (Smart et al. 2002).

Pre-plate development in mammals and reptiles

The most prominent pre-plate components are the Cajal-Retzius (CR) cells, which secrete high levels of Reelin (D’Arcangelo et al., 1995; Ogawa et al., 1995), and the aforementioned subplate cells (Allendoerfer and Shatz, 1994). The histogenetic inside-out principle, which is valid for all mammalian cortices, is closely related to the Reelin-Dab1 signalling pathway. The response of cortical plate neurons to the Reelin secreted by CR cells requires the Reelin-receptors VLDLR and ApoER2 and the intracellular adapter Disabled 1(Dab1) (reviewed by Bar et al., 2000). In Reelin-deficient reeler mice, the pre-plate fails to split and layer formation proceeds from outside to inside, giving rise to a grossly inverted cortex (Lambert de Rouvroit and Goffinet, 1998).

The importance of the Reelin-Dab1 pathway in controlling cortical architecture led to the suggestion that it might have been a driving factor in cortical evolution (Bar et al., 2000). Reelin expression has been studied in a large variety of vertebrates, from lamprey (Perez-Costas et al., 2002) to human (Meyer and Goffinet, 1998; Meyer et al., 2000). Reelin is present in the telencephalon of all vertebrates examined, but the cellular expression patterns are quite diverse. For instance, CR cells have not been detected in Danio rerio (zebrafish), even though a large proportion of telencephalic neurons are Reelin-positive (Perez-Garcia et al., 2001; Costagli et al., 2002). In amphibians, there is almost no radial migration and the rudimentary pallium is arranged in a periventricular gray matter. In Hyla meridionalis (Mediterranean treefrog), pallial cells are Reelin-negative but a few Reelin-positive neurons lie scattered just external to the periventricular cell layer (Perez-Garcia et al., 2001). Reelin mRNA expression has been exhaustively mapped in the lizard (Goffinet et al., 1999), turtle (Bernier et al., 1999), chick (Bernier et al., 2000) and crocodile (Tissir et al., 2003).

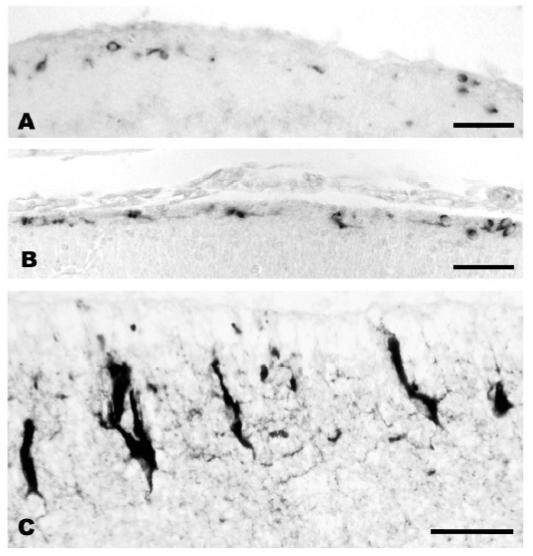

These studies indicate that CR-like cells are present in all amniotes, irrespective of architectonic patterns and migration gradients. However, a remarkable feature that supports a driving role of Reelin in cortical evolution is the increasing intensity of the Reelin signal in CR cells as cortical complexity evolves. The inside-out gradient is an evolutionary acquisition of the mammalian cortical plate; birthdating studies in reptiles show that in Emys (turtle) and Lacerta (lizard) the cortex develops from ouside to inside (Goffinet et al., 1986). The amplification of the Reelin signal in the marginal zone might have been an important step which, along with other factors, led from a single-layered reptilian-like cortex in the common amniote ancestor to the multilayered mammalian cortex (Bar et al., 2000). Another important point is the even higher increase of the Reelin-signal in the human marginal zone (Meyer and Goffinet, 1998), which is achieved through the structural differentiation of CR cells, most notably of their axonal plexus that forms a dense, compact fiber tract separating the cortical plate from the marginal zone (Meyer and Gonzalez Hernandez, 1993; Marin-Padilla, 1998; Fig. 6). In mice this axonal plexus is much less prominent than in humans, but Derer et al. (2001) showed that it contains secretory reservoirs of Reelin that are probably important for delivering the protein into the extracellular matrix. Likewise, a secretory human CR axonal plexus may allow the Reelin signal to diffuse and thereby increase the efficiency of the Reelin-Dab1 pathway of the human cortex (see Fig. 6C). Whatever happened during evolution the key developments were the changes in preplate structure and function and the appearance of the inside-out gradient in cortical plate formation. These changes paved the way to a larger cortex. However this could only be achieved if the mammalian neuroepithelium underwent the necessary changes to produce more cortical cells.

Figure 6.

Reelin-expressing Cajal-Retzius cells in lizard (A), mouse (B) and human (C) cortex during development. A, Cajal-Retzius cells in lizard embryo stage 38, B: in mouse embryo at E14, C: in human fetus 21 gestational weeks. Cajal-Retzius cells increase in numbers and morphological complexity in mammals. Bar in A and B: 40μm, in C: 20 μm.

Comparisons of the germinal zones: The elaboration of mitotic compartments might have been the drive behind mammalian cortical evolution

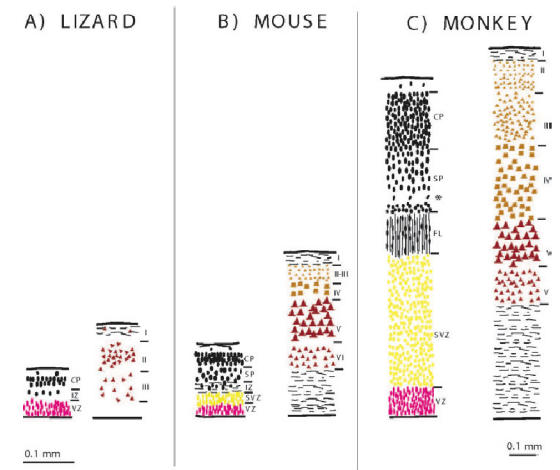

The rodent-monkey differences in the post-mitotic compartments are accompanied by major differences in the dimensions, configurations and developmental timing of the germinal zones. In rodents, the ventricular zone (VZ) is the major proliferative zone until well past mid corticogenesis (Fig 5). At E13 ab-ventricular mitotic figures herald the onset of the secondary germinal zone, referred to as the subventricular zone (SVZ) (Smart 1973), and from E15 onwards the VZ starts to decline, signalling the end of the major period of neuron production (Smart 1973; Smart and McSherry 1982). In addition to these zones cell proliferation has been reported in MZ, CP, IZ as well, both in rat and human brains (Carney et al., 2004). Recently, gene expression and mouse mutant analyses have indicated that the SVZ in rodents is the major compartment contributing to generation of upper layers (Tarabykin et al. 2001; also see Guillemot et al in this issue). But SVZ in rodents can account for no more than 35% of the cortical proliferative population at E15 (Takahashi et al. 1995). Accordingly, supragranular layers in rodents occupy not more than a third of the thickness of the mature cortex. In the macaque monkey, SVZ cells are found at a relatively earlier stage in corticogenesis (E55 -see Fig 5 for equivalence of developmental stages in mouse and monkey) and show a much greater expansion compared to the rodent, so that by mid-corticogenesis the SVZ has become the predominant germinal zone (Smart et al. 2002). This correlates with the predominance of supragranular layers in the mature primate cortex (Fig. 7B, Peters and Jones, 1985). The neurons of these layers do not project out of the cortex but instead connect different areas of the cortex or project locally. From E65 onwards, a specialised component of the SVZ, the outer (O) SVZ emerges in primates (Fig. 5). Histologically the OSVZ has very different features from the randomly organized cells that are typical of the subventricular zone described in rodents and the early pre-E65 SVZ in the monkey. The dense, radially orientated precursors of the OSVZ constitute a unique primate feature and birth-dating experiments show that it generates the supragranular layers of the cortex (Lukaszewicz et al., 2005). The predominance of OSVZ in primates could be due to the increased importance of the cortico-cortical connections and therefore the supragranular layers in this order. It is possible that differences in microenvironmental cues of SVZ and VZ are responsible for creating neuronal subtype diversity. Similarly, further compartmentalization of SVZ in primates may be a correlate of the higher neuronal diversity of supragranular layers (Peters and Jones, 1985). It has recently been demonstrated that there are important differences between the OSVZ of area 17 and 18 in the macaque cortex (Lukaszewicz et al., 2005). It will be interesting to further investigate these differences between simple cortices such as the retrosplenial areas compared to Area 17 or compare hippocampal development and three layered cortices of rodent and primate brains. The contribution of the neocortical SVZ to neuronal production seems to increase during evolution with the increasing complexity of the cortex (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

There is a strong correlation between the increase of supragranular layer complexity and the increase of subventricular zone between lizard (A) mouse (B) and monkey (C). The left panels for mouse and monkey are from Fig. 5 form an E15 mouse and a E72 monkey. The right panels represent the layering in the adult. Ventricular zone and layers VI and V are labelled red, subventricular zone and supragranular layers are colored yellow. Note the increase in the complexity of supragranular layers is accompanied with the increase of the subventricular zone during development. For the sake of clarity SVZ includes ISVZ and OSVZ in the monkey panel.

It has been noted that SVZ is rudimentary, if it exists at all in lizards (Goffinet, 1983). Martinez-Cerdeno et al. (2005) recently measured the proportions of the proliferative zones on HE stained sections of turtle, mouse and ferret and showed that in turtle only a rudimentary SVZ was present and the proportions of SVZ were higher in ferret. Work on embryonic turtle and chicken dorsal cortex revealed very few abventricular proliferation with H3 immunolabelling or with BrdU in dorsal cortex (A. Cheung, A. Tavare and Z. Molnár unpublished observations, 2005), but these dividing cells are more numerous other areas including nidopallium. These observations question the existence of a rudimentary SVZ in dorsal cortex of turtle and chicken. Amphibians might be similar in this respect (Wullimann et al., 2005). If these results are confirmed in more mammalian vertebrates, they suggest that SVZ is characteristic of the mammalian neocortex. Since SVZ is present in bird nidopallium and abventricular ploriferation is present here during development (A. Tavare, A. Cheung and Z. Molnár, unpublished observations, 2005), it is conceivable that birds have evolved this developmental mechanisms for the supragranular cell types independently (Butler and Hodods, 2005). The issue, whether the large SVZ is correlated with gyrencephalic mammalian brains should be further investigated in large Amazonian rodents with gyrencephalic brains (such as the agoti and capybara) and in primates with lyssencephalic brains (mouse lemur and marmoset). The comparative results may inspire us to have a fresh look at human lissencephalies (smooth brain, see below).

Comparative aspects of cell cycle parameters and cortical surface expansion

Cell-cycle duration of cortical precursors is considerably prolonged in macaque monkeys compared to mouse and rat. Whereas cell-cycle duration is approximately 17 hrs in the mouse at the time of supragranular layer neurogenesis, it reaches 28 hours in the VZ of macaque monkey visual cortex (Kornack and Rakic, 1998) and 36 hrs in the OSVZ (Lukaszewicz et al., 2005). Although, these observations are limited to a handful of species, and New World monkeys or other rodent species may differ, it can be hypothesized that the prolonged duration of cell-cycle in macaque monkey cortical precursors could be an adaptive feature underlying the evolutionary expansion of neocortex in primates (Rakic, 1995; Rakic, 2005). The results of Lukaszewicz et al. (2005) indicate that this feature is most prominent in the OSVZ. Environmental signals that contribute to determining cortical precursor fate have been shown to act on cycling precursors (McConnell and Kaznowski, 1991; Polleux et al., 2001) so that the extended duration of the primate cell-cycle may serve to ensure a fine adjustment of the rates of production of phenotypically defined neurons (Lukaszewicz et al, 2005). It is not known how evolutionary changes in developmental mechanisms have lengthened cortical progenitor cell cycle times in primates as compared to rodents and whether this rule extends to all rodents, including the species with gyrencephalic brains and all primates, including the species with lissencephalic brains.

Partitioning of the germinal zone in cortical mitotic compartments enables different environmental influences (e.g transcription factors and growth factors) to act in specific manners. There are numerous unanswered questions remaining that concern the embryonic compartments of the developing monkey cortex. For instance, the origin and role of the inner fibre layer that separates the ISVZ from the OSVZ is unknown. One possibility is that the outer fibre layer (OFL in Fig 5) houses the fibres from the lateral geniculate nucleus since it labels with acetylcholinesterase, an early marker of geniculocortical projections (Smart et al. 2002). If this is the case it suggests that thalamic fibres are much more closely connected to the germinal zone in primates compared to non-primates and supports the possibility that the ascending pathways influence rates of proliferation in the cortex and ultimately contribute to setting up distinct proliferative programmes in the germinal zone and possibly determining cortical cytoarchitecture (Lukaszewicz et al., 2005; Dehay et al. 2001; Carney et al., 2004; Carney, 2005). It has been demonstrated in vitro that thalamus can alter cell cycle parameters in embryonic cerebral cortical progenitor cells (Dehay et al., 2001).

In addition, it is likely that changes in the genetic control of cell cycle times are critical. One of the most potent regulators of the cell cycle in rodents is the Foxgl winged helix transcription factor (formerly called BF1). Foxgl belongs to a large family of Fox proteins, a family that has expanded greatly during evolution such that higher organisms have more Fox proteins (Lehmann et al., 2003; http://www.biology.pomona.edu/fox.html). In mice, Foxgl’s main site of expression is in proliferating progenitor cells throughout most of the telencephalic neuroepithelium from the neural plate stage onwards (Hatini et al., 1994; Xuan et al., 1995; Dou et al., 1999; Warren et al., 1999). Xuan et al. (1995) and Hebert and McConnell (2000) examined transgenic mice in which Foxg1 is disrupted by insertion of sequences encoding (β-galactosidase (Foxg1LacZ) or Cre recombinase (Foxg1Cre). Defects have not been detected in heterozygotes, but homozygotes die around birth and show hypoplasia of the entire telencephalon (Xuan et al., 1995; Dou et al., 1999; Pratt et al., 2002; Hanashima et al., 2002; Martynoga et al., 2005). The most detailed studies of the cell cycle effects of Foxgl knock-out in forebrain progenitor cells were performed in dorsal telencephalon (Hanashima et al., 2002; Martynoga et al., 2005). Loss of Foxg1 causes an abnormally rapid increase in the length of the cortical cell cycle after E11.5 and an increased rate of withdrawal of cortical cells from the cell cycle resulting in premature depletion of the progenitor cell pool. In humans, there are two genes homologous to murine Foxg1, known as FOXG1a and FOXG1b, which are likely to be involved in cortical progenitor proliferation and are clustered together on the same chromosome, suggesting that they evolved as a result of gene duplication (Wiese et al., 1995). Perhaps this genetic difference is an important factor in accounting for cell cycle differences between murine and human brains. Although speculative, the potential importance of FOX genes in human brain development is undeniable, with FOXP2, having recently been shown to be important in speech and language development (Lai et al., 2001).

Evolution did not finish with the production of the six layered mammalian isocortex evolved to be able to change its own development in response to the environment. While the basic structure of the neocortex is very similar in across mammals (Rockel et al. 1980), there are huge variations in cortical organization (Krubitzer and Kaas, 2005). The cerebral cortex shows both an enlargement and an increase in the number of cortical areas during evolution, as is typefied by the comparison of the brains of the mouse lemur, Microcebus, and the brain of European rodents (Cooper et al. 1979; Krubitzer and Kahn 2003). Numbers of functionally dedicated areas and size of cortex are not the only differences to be noted between mouse and macaque cortex. Another important difference is that Mouse is smooth brained (lissencephalic), while Macaques show pronounced cortical folding. These features of cortical organization have both been approached in genetic and comparative terms. For example evolutionary expansion of the cortex suggests amplification of the founder pool of cortical precursors (Rakic 1995; Rakic 2005). Increasing numbers of cortical areas could be due to afferent specification (Killackey 1990; Guillery, 2005) while gyrification is a result of regional variations in proliferation (Smart and McSherry 1986a,b). Although the functional significance of gyrification is still open to debate (Dehay et al. 1996; Van Essen 1997) it remains a major macroscopic feature that has to be seriously considered in any evolutionary developmental investigation of cortex (Smart and McSherry 1986a,b). It is important to point out that not all primates (over 200 species) show pronounced cortical folding. Several have only calcarine and lateral fissures (Butler and Hodos, 2005). There is an allometric relationship between brain size and folding. Thus, small primates such as the mouse lemur and marmoset have smooth brains, while large Amazonian rodents, such as the agoti and capybara have relatively deep sulci in their brains. Understanding the formation of sulci and gyri is important for the comprehension of human mutations causing lissencephaly. Again, genetic and comparative approaches could contribute to the solution.

Necessity of comparative studies for understanding human cortical developmental disorders

Comparing rodents (including smooth and folded brained species) and primates (including species with small and large brains) is necessary to define species differences in the expression of those genes and gene products where mutations cause human lissencephaly (smooth brain). Since the mouse is the principal model for experimental genetics, the question is whether the normally lissencephalic mouse brain can be compared directly to the highly convoluted human brain. In previous sections of this review the main differences between rodent and primate corticogenesis have been outlined (Figs. 5 and 7). Monkey and human cortex are similar in the large size and protracted time table of SVZ, IZ and subplate development, which greatly differ from their homologous compartments of the rodent.

The example of Doublecortin (DCX) can best illustrate the difficulties in comparing mouse and human gene mutation defects (see also review ‘Human disorders of cortical development’ by Francis et al in this issue). The human DCX gene maps to chromosome Xq22.3-q23 (desPortes et al, 1998a, Gleeson et al, 1998) and encodes a protein that is associated with microtubules (Gleeson et al., 1999; Francis et al., 1999). Male patients have classical type I lissencephaly - a thickened, almost smooth cortex with abnormal layering- accompanied by severe mental retardation and epilepsy (Harding 1996). Females who are heterozygous for DCX mutations have subcortical laminar heterotopia (SCLH) (desPortes et al, 1998b, Gleeson, 2000), a less severe malformation where an ectopic band of neurons lies in the white matter below an almost normal cortex, thus usually causing epilepsy. Surprisingly, inactivation of the Dcx gene in mice does not reproduce the severe brain defect known from human mutations, but instead produces only a minor layering abnormality in the hippocampus (Corbo et al, 2002, Kappeler et al, submitted).

A possible explanation for this discrepancy can be found in the normal expression pattern of DCX in the human brain (Meyer et al., 2002). DCX is first expressed at 5GW in radial columns in the marginal layer. At 7GW, still a relatively early stage of human corticogenesis, it appears in tangentially oriented neurons in the SVZ, and from 8GW onward it is most prominent in horizontal neurons and fibers in SVZ and IZ, while the VZ is DCX -negative. A similar expression pattern is also observed in the monkey cortex (Dehay, unpublished). In the cortical plate, DCX expression is less intense and mostly localized to radial processes in the upper layers. On the whole, the pattern is consistent with DCX involvement in non-radial migration, and in fact DCX expression was found to often colocalize with calretinin, a marker of cortical interneurons (Meyer et al., 2002). The possibility that migration of interneurons is particularly affected in type I lissencephalies has been addressed recently (Pancoast et al, 2005, and G.M/F.F. in prep). Dcx distribution in mouse brain appears less conspicuous, probably due to the smaller size of the SVZ and the heavy Dcx labelling of fibres in the compact IZ, masking migrating cells in this zone. Nevertheless, a clear expression of Dcx in horizontally oriented, apparently tangentially migrating, neurons was observed (Francis et al, 1999). Supporting a role for Dcx in migrating interneurons and the comparability of Lis1 mouse mutants (McManus et al, 2004), mild interneuron migration abnormalities have also been detected in Dcx knockout mice (Kappeler et al, submitted). Nevertheless the human disorder remains markedly more severe.

With regard to the question of rodent-human comparisons, we thus learn from DCX that it is expressed precisely in those cortical compartments, SVZ and IZ, which are rudimentary in rodents, but highly differentiated in primates (Figs. 5 and 7). Thus it is perhaps not surprising that mouse knockouts poorly mimic the human disorder. Clearly, if the cellular and molecular mechanisms were the same in mouse and man, the mouse would have a large convoluted cortex. Comparative studies are therefore very important to recognize the limitations of generalizations across species. Studies involving DCX, along with genes involved in human microcephaly (see review ‘Human disorders of cortical development’ by Francis et al. in this issue), are clearly most important for a better understanding primate brain evolution. Moreover, evolutionary theories can also be further tested by examining human developmental disorders (e.g. see Molnár and Butler, 2002a).

Concluding remarks

This review aimed to examine the comparative aspects of cortical development. Unfortunately there are only a handful of experimental model systems used in comparative developmental studies and the current comparisons are limited to a few mammals (rat, mouse, macaque monkey and human), chicken and turtle. Unfortunately little quantitative information is present even in these model systems. By examining neurogenesis, layer formation of the first postmitotic cells, radial migration of neurons within the cortex and tangential migration of GABAergic neurons from the subpallium we can speculate on the evolutionarily relevant changes of cortical development. The formation of the first generated cell layers and the presence of the reelin signalling pathway are similar in mammals, birds and reptiles. The subpallial origin and tangential migration of GABAergic neurons are also surprisingly conserved across most species studied. However, there are major transformations at the striatocortical junction, in the cortical germinal zones and in the amplification of the reelin signalling pathway, which might all have contributed to the evolution of the mammalian neocortical development. Comparative developmental studies also reveal distinct primate features in the early compartments of the developing brain and suggest that the elaboration of the mitotic compartments could constitute a major drive behind mammalian cortical evolution. Comparative developmental biology draws our attention to the limitations of some of the model systems currently used to understand human cortical developmental abnormalities. Several gene functions implicated in human cortical developmental disorders have been studied in transgenic mouse models. While this approach has been extremely useful and has revolutionized the study of mammalian cortical developmental programs, recent comparative analyses reveals considerable differences. These distinctions will have to be taken into account when we study the range of gene function implicated in human brain developmental abnormalities (including childhood epilepsy, schizophrenia, autism and attention deficit disorder).

Bibliography

- Anderson SA, Qiu M, Bulfone A, Eisenstat DD, Meneses J, Pedersen R, Rubenstein JL. Mutations of the homeobox genes Dlx-1 and Dlx-2 disrupt the striatal subventricular zone and differentiation of late born striatal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Kaznowski CE, Horn C, Rubenstein JL, McConnell SK. Distinct origins of neocortical projection neurons and interneurons in vivo. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:702–709. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angevine JB, Sidman RL. Autoradiographic study of cell migration during histogenesis of cerebral cortex in the mouse. Nature. 1961;192: 766–768. doi: 10.1038/192766b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu Y. Latexin: a molecular marker for regional specification in the neocortex. Neurosci Res. 1994;20(2):131–5. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA, Ragsdale CW. Identification of a Pax6 dependent epidermal growth factor family signaling source at the lateral edge of the embryonic cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6399–03. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06399.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar I, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM. The evolution of cortical development. An hypothesis based on the role of the Reelin signaling pathway. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:633–638. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Altman J. Development of layer I and the subplate in the rat neocortex. Exp Neurology. 1990;107:48–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(90)90062-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier B, Bar I, D’Arcangelo G, Curran T, Goffinet AM. Reelin mRNA expression during embryonic brain development in the chick. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;422:448–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier B, Bar I, Pieau C, Lambert De Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM. Reelin mRNA expression during embryonic brain development in the turtle Emys orbicularis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;413:463–479. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991025)413:3<463::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielle F, Griveau A, Narboux-Neme N, Vigneau S, Sigrist M, Arber S, Wassef M, Pierani A. Multiple origins of Cajal-Retzius cells at the borders of the developing pallium. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8):1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nn1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MG, Kriegstein AR. Appearance of putative amino acid neurotransmitters during differentiation of neurons in embryonic turtle cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1991;310:571–592. doi: 10.1002/cne.903100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MG, Shen JM, Kriegstein AR. Evidence for the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid in aspiny and sparsely spiny nonpyramidal neurons of the turtle dorsal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1987;259:277–297. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce LL, Neary TJ. The limbic system of tetrapods: a comparative analysis of cortical and amygdalar populations. Brain, Behaviour and Evolution. 1995;46:224–234. doi: 10.1159/000113276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AB, Molnár Z. Development and evolution of the collopallium in amniotes: a new hypothesis of field homology. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57(3–4):475–9. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AB. The evolution of the dorsal thalamus of jawed vertebrates, including mammals: cladistic analysis and a new hypothesis. Brain Research Reviews. 1994;19:29–65. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AB, Hodos W. Comparative vertebrate neuroanatomy. 2. Wiley and Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carney R. DPhil Thesis. University of Oxford; Thesis: 2005. Thalamocortical Development and Cell Proliferation in Fetal Primate and Rodent Cortex. [Google Scholar]

- Carney RSE, Molnar Z, Giroud P, Cortay V, Berland M, Kennedy H, Dehay C. FENS Abstr. Thalamocotical projections in the developing primate cortex. 2002;1:A007.06. [Google Scholar]

- Carney RSE, Bystron I, Blakemore C, Molnár Z, López-Bendito G. Radial glial cell proliferation outside the proliferative zone: a quantitative study in fetal rat and human cortex. FENS Abstract. 2004:A145.4. [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Puelles L, Martinez S. The avian telencephalic subpallium originates inhibitory neurons that invade tangentially the pallium (dorsal ventricular ridge and cortical areas) Dev Biol. 2001;239:30–45. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM, Kennedy H, et al. Thalamic projections to area 17 in a prosimian primate, Microcebus murinus. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187(1):145–167. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagli A, Kapsimali M, Wilson SW, Mione M. Conserved and divergent patterns of Reelin expression in the zebrafish central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;450:73–93. doi: 10.1002/cne.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Valverde F. Dynamics of cell migration from the lateral ganglionic eminence in the rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16(19):6146–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06146.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Giroud P, et al. Contribution of thalamic input to the specification of cytoarchitectonic cortical fields in the primate: effects of bilateral enucleation in the fetal monkey on the boundaries, dimensions, and gyrification of striate and extrastriate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1996;367(1):70–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960325)367:1<70::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Savatier P, et al. Cell-cycle kinetics of neocortical precursors are influenced by embryonic thalamic axons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:201–214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00201.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derer P, Derer M, Goffinet AM. Axonal secretion of Reelin by Cajal-Retzius cells: Evidence from comparison of normal and Rein Orl mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440: 136–143. doi: 10.1002/cne.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- des Portes V, Francis F, Pinard J-M, Desguerre I, Moutard M-L, Snoeck I, Meiners LC, Capron F, Cusmai R, Ricci S, Motte J, Echenne B, Ponsot G, Dulac O, Chelly J, Beldjord C. Doublecortin is the major gene causing X-linked Subcortical Laminar Heterotopia (SCLH) Hum Mol Gen. 1998b;7:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- des Portes V, et al. A novel CNS gene required for neuronal migration and involved in X-linked subcortical laminar heterotopia and lissencephaly syndrome. Cell. 1998a;92:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80898-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou CL, Li S, Lai E. Dual role of Brain Factor-1 in regulating growth and patterning of the cerebral hemispheres. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9: 543–550. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AS, Pieau C, Reperant J, Boncinelli E, Wassef M. Expression of the Emx-1 and Dlx-1 homeobox genes define three molecularly distinct domains in the telencephalon of mouse, chick, turtle and frog embryos: implications for the evolution of telencephalic subdivisions in amniotes. Development. 1998;125:2099–2111. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis F, Koulakoff A, Boucher D, Chafey P, Schaar B, Vinet MC, Friocourt G, McDonnell N, Reiner O, Kahn A, McConnell SK, Berwald-Netter Y, Denoulet P, Chelly J. Doublecortin is a developmentally regulated, microtubule-associated protein expressed in migrating and differentiating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-zerdugo JM, Llahi S, Ferrer I, Lopez-Garcia C. Postnatal neurogenesis in the olfactory bulbs of a lizard. A tritiated thymidine autoradiographic study. Neurosci Lett. 1989;98:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Shatz CJ. Involvement of subplate neurons in the formation of ocular dominance columns. Science. 1992;255:5050–1441. 1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1542795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, et al. Doublecortin, a brain-specific gene mutated in human X-linked lissencephaly and double cortex syndrome, encodes a putative signaling protein. Cell. 1998;92:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet AM, Daumerie C, Langerwerf B, Pieau C. Neurogenesis in reptilian cortical structures: 3H-thymidine autoradiographic analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1986;243:106–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.902430109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet AM. The embryonic development of the cortical plate in reptiles: a comparative study in Emys orbicularis and Lacerta agilis. J Comp Neurol. 1983;215:437–452. doi: 10.1002/cne.902150408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet AM, Rakic P, editors. Mouse brain development. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Talley T, Qiu M, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, Jones KR. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1 -expressing lineage. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6309–6314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW. Is postnatal neocortical maturation hierarchical? Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanashima C, Shen L, Li SC, Lai E. Brain factor-1 controls the proliferation and differentiation of neocortical progenitor cells through independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6526–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding B. Gray matter heterotopia. In: Guerrini R, Andermann F, Canapicchi R, Roger J, Zilfkin B, Pfanner P, editors. Dysplasias of Cerebral Cortex and Epilepsy. Philadelphia/New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hatini V, Tao W, Lai E. Expression of winged helix genes, BF-1 and BF-2, define adjacent domains within the developing forebrain and retina. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1293–309. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert J, McConnell SK. Targeting of ere to the Foxgl (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev. Biol. 2000;222: 296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RE, Favor J, Hogan BL, Ton CC, Saunders GF, Hanson IM, Prosser J, Jordan T, Hastie ND, van Heyningen V. Mouse small eye results from mutations in a paired-like homeobox-containing gene. Nature. 1991;354:522–5. doi: 10.1038/354522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis ED, Gunturkun O, Bruce L, Csillag A, Karten H, Kuenzel W, Medina L, Paxinos G, Perkel DJ, Shimizu T, et al. Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:151–159. doi: 10.1038/nrn1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Lopez-Bendito G, Gruss P, Stoykova A, Molnr Z. Pax6 is required for the normal development of the forebrain axonal connections. Development. 2002;129(21):5041–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappeler C, Saillour Y, Baudouin J-P, Phan Dinh Tuy F, Alvarez C, Houbron C, Caspar P, Hamard G, Chelly J, Metin C, Francis F. Doublecortin knockout mice show branching and nucleokinesis defects in migrating interneurons. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl062. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ. The organization of the avian telencephalon and some speculations on the phylogeny of the amniote telencephalon. In: Noback CR, Petras JM, editors. Comparative and Evolutionary Aspects of Vertebrate Central Nervous System, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 167. 1969. pp. 146–179. [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ. Evolutionary developmental biology meets the brain: the origins of mammalian cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey HP. Neocortical expansion: an attempt towards relating phylogeny and ontogeny. J Cognit Neurosci. 1990;2:1–17. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1990.2.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AS, Anderson SA, Rubenstein JL, Lowenstein DH, Pleasure SJ. Pax-6 regulates expression of SFRP-2 and Wnt-7b in the developing CNS. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. Changes in cell-cycle kinetics during the development and evolution of primate neocortex. PNAS. 1998;95:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostovic I, Rakic P. Develomental history of the transient subplate zone in the visual cortex of the macaque monkey and human brain. J Comp Neurol. 1990;297:441–470. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll TK, O’Leary DDM. Ventralized dorsal telencephalic progenitors in Pax6 mutant mice generate GABA interneurons of a lateral ganglionic eminence fate. 2005;102(20):7384–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500819102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L, Kaas J. The evolution of the neocortex in mammals: how is phenotypic diversity generated? CurrOpin Neurobiol. 2005;15(4):444–53. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L, Kahn DM. Nature versus nurture revisited: an old idea with a new twist. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(1):33–52. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CS, Fisher SE, Hurst JA, Vargha-Khadem F, Monaco AP. A forkhead-domain gene is mutated in a severe speech and language disorder. Nature. 2001;413:519–23. doi: 10.1038/35097076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM. The reeler mouse as a model of brain development. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 1998;150:1–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavdas AA, Grigoriou M, Pachnis V, Parnavelas JG. The medial ganglionic eminence gives rise to a population of early neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7881–7888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07881.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann OJ, Sowden JC, Carlsson P, Jordan T, Bhattacharya SS. Fox’s in development and disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19:339–44. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K, Zoncu R, Rakic P. Origin of GABAergic neurons in the human neocortex. 2002 doi: 10.1038/nature00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K, Rakic P. Telencephalic origin of human thalamic GABAergic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:931–936. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G, Sturgess K, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, Molnr Z, Paulsen O. Preferential origin and layer destination of GAD65-GFP cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1122–1133. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewicz A, Savatier P, Cortay V, Giroud P, Huissoud C, Berland M, Kennedy H, Dehay C. G1 phase regulation, area-specific cell-cycle control and cytoarchitectonics in the primate cortex. Neuron. 2005;(47):353–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB, Shatz CJ. Studies of the earliest generated cells of the cat’s visual cortex: cogeneration of subplate and marginal zones. J Neurosci. 1985;5(4):1062–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-01062.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O, Rubenstein JL. A long, remarkable journey: tangential migration in the telencephalon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(11):780–90. doi: 10.1038/35097509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Dual origin of the mammalian neocortex and evolution of the cortical plate. Anat Embryol. 1978;152: 109–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00315920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Cajal-Retzius cells and the development of the neocortex. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:64–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynoga B, Morrison H, Price DJ, Mason JO. Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Dev Biol. 2005;283:113–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell SK, Kaznowski CE. Cell cycle dependence of laminar determination in developing neocortex. Science. 1991;254:282–285. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MF, Nasrallah IM, Pancoast MM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Golden JA. Lis1 is necessary for normal non-radial migration of inhibitory interneurons. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:775–784. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Ferro M, Perez-Costas E, Villar-Cheda B, Abalo XM, Rodriguez-Munoz R, Rodicio MC, Anadon R. Ontogeny of gamma-aminobutyric acid-immunoreactive neuronal populations in the forebrain and midbrain of the sea lamprey. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446:360–376. doi: 10.1002/cne.10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métin C, Baudoin J-P, Rakiæ S, Parnavelas JG. Cell and molecular mechanisms involved in the migration of cortical interneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Goffinet AM. Prenatal development of reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the human neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;397:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, González-Hernández T. Developmental changes in layer I of the human neocortex during prenatal life: a Oil-tracing and AChE and NADPH-d histochemistry study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;338:317–336. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Schaaps JP, Moreau L, Goffinet AM. Embryonic and early fetal development of the human neocortex. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1858–1868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Pérez-García CG, Gleeson JG. Selective expression of Doublecortin and Lis1 in the developing human cortex suggests unique modes of neuronal movement. Cerebral Cortex. 2002a;12:1225–1236. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Butler AB. The corticostriatal junction: a crucial region for forebrain development and evolution. Bioessays. 2002a;24(6):530–41. doi: 10.1002/bies.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Butler AB. Neuronal changes during forebrain evolution in amniotes: an evolutionary developmental perspective. Prog Brain Res. 2002b;136:21–38. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah B, Alifragis P, Wong RO, Parnavelas JG. Ventricle-directed migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:218–224. doi: 10.1038/nn813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah B, Parnavelas JG. Modes of neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:423–432. doi: 10.1038/nrn845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor SC, Martinez-Cerdeno V, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR. Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(2):136–44. doi: 10.1038/nn1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt RG, Kaas JH. The emergence and evolution of mammalian neocortex. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93932-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, Yamamoto H, Mikoshiba K. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancoast M, Dobyn W, Golden JA. Interneuron deficits in patients with the Miller-Dieker lissencephaly. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109: 400–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0979-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnavelas JG. The origin and migration of cortical neurones: new vistas. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(3): 126–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Canellas MM, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Adult neurogenesis in the telencephalon of a lizard: a [3H]thymidine autoradiographic and bromodeoxyuridine immunocytochemical study. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;93:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Canellas MM, Font E, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Postnatal neurogenesis in the telencephalon of turtles: evidence for nonradial migration of new neurons from distant proliferative ventricular zones to the olfactory bulbs. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;101:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Costas E, Melendez-Ferro M, Santos Y, Anadon R, Rodicio MC, Caruncho HJ. Reelin immunoreactivity in the larval sea lamprey brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2002;23:211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(01)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-García CG, González-Delgado FJ, Suárez-Solá ML, Castro-Fuentes R, Martm-Trujillo JM, Ferres-Torres R, Meyer G. Reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the adult vertebrate pallium. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2001;21:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Jones EG, editors. Visual Cortex. Vol. 4. Association and Auditory Cortices, Plenum Press; New York-London: 1985. Cerebral Cortex, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Polleux F, Dehay C, Goffinet A, Kennedy H. Pre- and post-mitotic events contribute to the progressive acquisition of area-specific connectional fate in the neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:1027–1039. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.11.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt T, Quinn JC, Simpson TI, West JD, Mason JO, Price DJ. Disruption of early events in thalamocortical tract formation in mice lacking the transcription factors Pax6 or Foxg1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8523–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08523.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles L, Kuwana E, Puelles E, Bulfone A, Shimamura K, Keleher J, Smiga S, Rubenstein JL. Pallial and subpallial derivatives in the embryonic chick and mouse telencephalon, traced by the expression of the genes Dlx-2, Emx-1, Nkx-2.1, Pax-6, and Tbr-1. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:409–438. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000828)424:3<409::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raedler E, Raedler A. Autoradiographic study of early neurogenesis in rat neocortex. Anat. Embryol. 1978;154: 267–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00345657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Less is more: progenitor death and cortical size. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8): 981–2. doi: 10.1038/nn0805-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Vive la difference! Neuron. 47. 2005;3:323–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. A small step for the cell, a giant leap for mankind: a hypothesis of neocortical expansion during evolution. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18(9):383–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93934-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A. A comparison of neurotransmitter-specific and neuropeptide-specific neuronal cell types present in the dorsal cortex in turtles with those present in the isocortex in mammals: implications for the evolution of isocortex. Brain Behav Evol. 1991;38:53–91. doi: 10.1159/000114379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A. Neurotransmitter organization and connections of turtle cortex: implications for the evolution of mammalian isocortex. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1993;104A:735–748. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(93)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A. A hypothesis as to the organization of cerebral cortex in the common amniote ancestor of modern reptiles and mammals. In: Bock GR, Cardew G, editors. Evolutionary Developmental Biology of the Cerebral Cortex, Novartis Fondation Symposium 228. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 83–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Perkel DJ, Bruce LL, Butler AB, Csillag A, Kuenzel W, Medina L, Paxinos G, Shimizu T, Striedter G, Wild M, Ball GF, Durand S, Gunturkun O, Lee DW, Mello CV, Powers A, White S A, Hough G, Kubikova L, Smulders TV, Wada K, Dugas-Ford J, Husband S, Yamamoto K, Yu J, Siang C, Jarvis ED. Revised nomenclature for avian telencephalon and some related brainstem nuclei. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;473: 377–414. doi: 10.1002/cne.20118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockel AJ, Hiorns RW, Powell TP. The basic uniformity in structure of the neocortex. Brain. 1980;103(2):221–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardigli R, Bäumer N, Gruss P, Guillemot F, Le Roux I. Direct and concentration-dependent regulation of the proneural gene Neurogenin2 by Pax6. Development. 2003;130:3269–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IHM. Proliferative characteristics of the ependymal layer during the early development of the mouse neocortex: a pilot study based on recording the number, location and plane of cleavage of mitotic figures. J Anat. 1973;116(1):67–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IHM, McSherry GM. Growth patterns in the lateral wall of the mouse telencephalon: II. Histological changes during and subsequent to the period of isocortical neuron production. J Anat. 1982;134(3):415–442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IHM, McSherry GM. Gyrus formation in the cerebral cortex in the ferret. I. description of the external changes. J Anat. 1986;146:141–152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IHM, McSherry GM. Gyrus formation in the cerebral cortex of the ferret. II. Description of the internal histological changes. J Anat. 1986;147:27–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IHM, Smart M. Growth patterns in the lateral wall of the mouse telencephalon: I. Autoradiographic studies of the histogenesis of the isocortex and adjacent areas. J Anat. 1982;134:273–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IH, Dehay C, et al. Unique morphological features of the proliferative zones and postmitotic compartments of the neural epithelium giving rise to striate and extrastriate cortex in the monkey. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(1):37–53. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Fernandez A, Pieau C, Reperant J, Boncinelli E, Wassef M. Expression of the Emx1-1 and Dlx-1 homeobox genes define three molecularly distinct domains in the telencephalon of mouse, chick, turtle and frog embryos: implications for the evolution of telencephalic subdivisions in amniotes. Development. 1998;125: 2099–2111. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]