Abstract

Background

Recruitment of participants for clinical trials requires considerable effort and cost. There is no research on the cost-effectiveness of recruitment methods for an obesity prevention trial of young children.

Methods

This study determined the cost-effectiveness of recruiting 70 families with a child aged 4 to 7 (5.9 ± 1.3) years in Western New York from February, 2003 to November, 2004, for a two year randomized obesity prevention trial to reduce television watching in the home.

Results

Of the 70 randomized families, 65.7% (n = 46) were obtained through direct mailings, 24.3% (n = 17) were acquired through newspaper advertisements, 7.1 % (n = 5) from other sources (e.g. word of mouth), and 2.9% (n = 2) through posters and brochures. Costs of each recruitment method were computed by adding the cost of materials, staff time, and media expenses. Cost-effectiveness (money spent per randomized participant) was US $0 for other sources, US $227.76 for direct mailing, US $546.95 for newspaper ads, and US $3,020.84 for posters and brochures.

Conclusion

Of the methods with associated costs, direct mailing was the most cost effective in recruiting families with young children, which supports the growing literature of the effectiveness of direct mailing.

Keywords: Recruitment, Cost analysis, Prevention trials, Direct Mail, Advertising, Child

Introduction

Implementing a randomized clinical trial requires recruiting a representative sample of participants within time and budget constraints. Recruitment of healthy individuals for prevention studies may be particularly challenging (Kidd, Parshall, Wojcik, & Struttmann, 2004; Linnan et al., 2002), as they may discount the importance of their involvement or see little personal benefit for participating in the study. Recruiting children may be further complicated by the necessity to engage one or more other family members. As a result of recruiting challenges, researchers often extend the recruitment period, add new enrollment sites, or modify inclusion criteria to reach their goals.

Direct mailing is one recruitment strategy that has been targeted to diabetics (Rubin et al., 2002), smokers (McIntosh, Ossip-Klein, Spada, & Burton, 2000), minorities (Kiernan, Phillips, Fair, & King, 2000), and individuals at risk for hypertension and cardiovascular diseases (Borhani et al., 1989). Personalized letters and phone follow-up are key elements that increase effectiveness of direct mailing (Kiernan et al., 2000; Lovato et al., 1997).

Newspaper advertisements and media are an alternative strategy that can promote widespread awareness and create a positive image of a study (Levenkron & Farquhar, 1982). Successful enrollment of participants may require follow-up by mail or telephone (Levenkron & Farquhar, 1982). Comprehensive recruitment programs employ overlapping strategies simultaneously (Bjornson-Benson et al., 1993), with ongoing assessment of relative rates of enrollment and cost-effectiveness of methods which makes it possible to allocate resources to the most successful methods (Lovato et al., 1997).

This paper reports the cost-effectiveness of 3 methods to recruit families with children aged 4 to 7 years for a two year randomized obesity prevention trial by reducing television watching. To our knowledge, this is the first study documenting cost-effectiveness of recruitment strategies for an obesity prevention program in young children.

Methods

Participants

Seventy families were recruited for a 2 year study that evaluated the effects of modifying the home television watching environment of 4-7 year-old children. Eligibility criteria included that the child was 1) at the 75th BMI percentile or greater, 2) used the television and/or computer for at least 14 hours per week, and 3) did not have any serious medical conditions. Body mass index was calculated according to the following formula: BMI = kg/m2. The 75th BMI percentile was calculated in relationship to the 50th BMI percentile for children based on their sex and age (Kuczmarski et al., 2002).

Procedures

Parents completed a phone screen that assessed the child’s height, weight, number of television and computer hours used by the child per week, and recruitment method (direct mailing, newspaper advertisements, posters and brochures, and other sources, such as word of mouth or referrals from other studies).

Eligible families attended an orientation, and if interested signed an informed consent document approved by the University at Buffalo Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment strategies

Direct Mailing

Two direct mailing lists were used. The first address list of 19,805 families with 4-7 year-old children for Buffalo/Niagara metropolitan area, (infoUSA® Inc., Papillion, NE) cost $1114.03 (all costs are reported in US dollars) plus $25.00 shipping. The database company obtains its information from public sources.

The first batch of letters was mailed to 1500 families in November, 2003, while four subsequent batches of approximately 3000 letters were mailed in bi-monthly increments, including 600 minorities. Zip codes closest to the University were mailed to first, with subsequent mailings being further, excluding zip codes greater than 25 miles from the University. Overall, 2.6% were returned due to incorrect address (number of envelopes returned/number of envelopes sent * 100). Families who had already contacted us about the study were removed from direct mailing lists to reduce multiple or repeated exposure.

The second list of 2000 names of University employees was obtained free of charge from the State University of New York at Buffalo. Letters were sent to 700 employees in October 2003, with 7.2% returned due to incorrect address.

Mailings were in sealed envelopes that contained a personally signed letter with the study logo at the top along with a black and white brochure (Kiernan et al., 2000) titled ‘Don’t Slouch on the Couch.’ The brochure listed general facts about television watching and benefits of watching less.

Newspaper Advertisements

Newspaper advertisements were placed in the region’s largest Metropolitan daily newspaper, a free weekly local paper, and a minority specific weekly newspaper with distributions of 349,598; 215,000; and 10,000 households, respectively. A 2” by 3.5” ad in the regional newspaper cost $1,133.65 per day and was run on four Sundays over an eight month period beginning February, 2003. The advertisement was designed and prepared by study staff and contained a larger bolded first line to attract interest (Do You Have A Child Between 4 and 7 years of age?), a brief description of the study, a picture of a young child on a bicycle, a sentence about time commitment and compensation with a picture of a dollar bill, contact information, and the University logo. Newspaper advertisements were begun prior to direct mailings based on research suggesting that newspaper advertisements promote widespread awareness and can create a positive image of a study (Levenkron & Farquhar, 1982).

A 3.25” by 3” version of the advertisement was placed eight times in the free weekly local newspaper over a 12 month period, beginning in October, 2003. Newspaper staff altered the original advertisement and suggested a design using the same wording, with the picture altered to represent the season. The average cost per advertisement was $267.47.

Finally, an advertisement was placed in the minority specific newspaper with weekly circulation to 10,000 subscribing homes, businesses, gas stations, and other public locations. The first advertisement consisted of an 8 1/2” by 11” flier inserted into 7,500 papers in November, 2004. The flier was an enlarged version of our typical newspaper ad with a picture of a child watching television on the couch, and cost $562.50 to place. In the same paper, a 4” by 5” ad identical to the flier, which cost $140.00, was published the following week.

Posters and Brochures

A graphic designer created professional posters (17” × 11”) and two 8” × 8” six color study brochures entitled ‘Don’t Slouch on the Couch.’ A tear-off pad in a business card format with the study contact information was attached to the bottom right hand corner of each poster. Posters, brochures, and display stands were mailed or hand delivered to schools, churches, and doctor’s offices at their request. Black and white brochures were used in the direct mailings.

Other Sources

Other sources included recruitment of participants by word of mouth.

Costs

Total costs for materials, staff time, and media expenses were computed for each recruitment method. Material costs for direct mailing included the mailing list, letter and brochure design, printing, postage, envelopes, and labels. Newspaper advertisements require staff time for the advertisement design and placement. The expenses for posters and brochures included the original design, printing fees, mailing supplies for community distribution, and staff time to meet with the graphic designer. Graduate students assembled the direct mailings at $10.00 per hour, which is the standard graduate student pay in our laboratory. Staff time allotted to the other methods was assessed at $18.50 per hour [(annual salary + benefits)/actual billable hours]. Recruitment methods categorized as other sources did not incur any associated costs.

Results

The demographics of the recruited sample are in Table 1. Thirty-six families were randomized to the intervention group and 34 to the control group for a total of 70. The sample included 24.3% ethnic minorities. Chi-square tests revealed no significant differences between groups for sex or ethnicity. One-way ANOVAS were calculated separately for age, BMI, people residing in the home, and baseline television and computer hours per week, and revealed no significant differences between groups. Analyses were completed using SYSTAT software (SYSTAT, 2004).

Table 1.

Demographics of recruited sample in Western New York (February, 2003 - November, 2004).

| Group (N=70) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental (n = 36) | Control (n = 34) | |||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Age (years) | 5.81 | 1.20 | 6.05 | 1.33 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.27 | 2.48 | 19.13 | 3.49 |

| Environment | ||||

| People residing in the home | 4.31 | 0.82 | 4.27 | 0.86 |

| Baseline TV and computer (hours/week) | 26.50 | 11.31 | 27.15 | 9.89 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 19 | 52.8 | 18 | 52.9 |

| Girls | 17 | 47.2 | 16 | 47.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 28 | 77.8 | 25 | 73.5 |

| African American | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 11.8 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 11.1 | 3 | 8.8 |

| More than one race | 4 | 11.1 | 2 | 5.9 |

Note: BMI = Body mass index

Of the 675 families screened by phone, 183 were eligible for screening, resulting in 70 enrolled families. Direct mail generated the most phone screens and recruited the most families (Table 2) with the fewest number of phone screens per randomized family (7.5). Newspaper ads recruited the second most families with a mean of 14.1 phone screens per participant. Other sources and posters and brochures generated much fewer phone screens and randomized families, with means of 8.6 and 12.5 phone screens per participant, respectively. The unknown category represents the participants for which there is no source of referral information (caller unable to name source, etc). Referral information is available for all randomized families.

Table 2.

Distribution of method of recruitment by number of phone screens, eligible families, and randomized families in Western New York (February, 2003 - November, 2004).

| Recruitment method | Phone screens (n = 675) | Eligible families (n = 183) | Randomized families (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct mail | 347 (51.4%) | 103 (56.3%) | 46 (65.7%) |

| Newspaper ads | 240 (35.6%) | 59 (32.2%) | 17 (24.3%) |

| Regional | 125 | 25 | 5 |

| Local | 100 | 30 | 11 |

| Minority specific | 15 | 4 | 1 |

| Other sources | 43 (6.4%) | 11 (6.0%) | 5 (7.1%) |

| Posters and brochures | 25 (3.7%) | 8 (4.4%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Unknown | 20 (3.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) |

The total cost to recruit 70 randomized families was $25,817.06. The average cost per randomized family was $368.82, with a range of $227.76 to $3,020.84 for each method. By removing the five families that were recruited without cost through other sources, the average cost rose slightly to $397.19 per family.

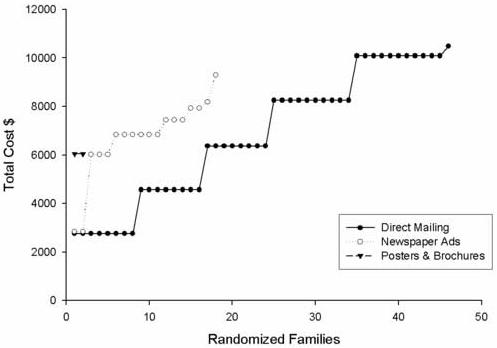

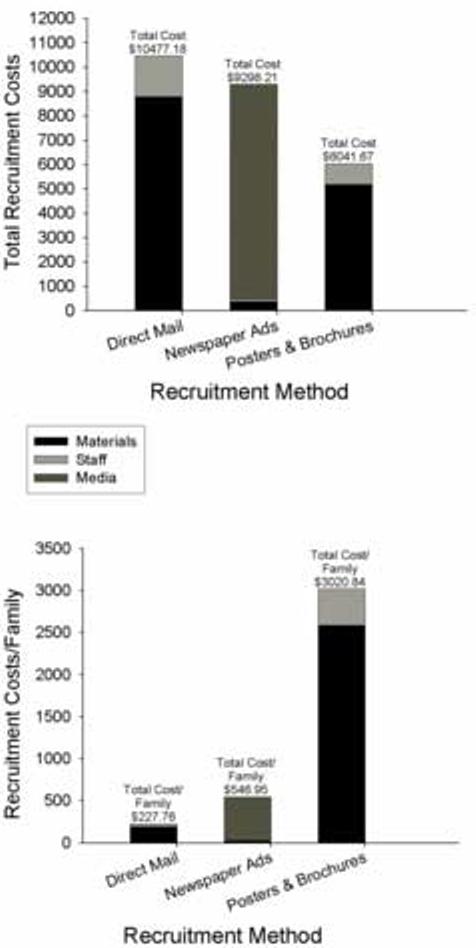

Figure 2 top shows that direct mailing expenditures were higher than the other recruitment methods in materials, staff time, and total costs, but since more families were recruited using this method, the costs per randomized family were the lowest (Figure 2 bottom). Newspaper advertisements consumed all of the media expenses with total costs of $9,298.21 ($1,114.50 for the minority specific paper, $2,172.13 for the local paper, and $6,011.58 for the regional paper).

Figure 2.

Cumulative costs by recruitment method in Western New York (February, 2003 - November, 2004). Each bullet indicates a successive randomized family. The cumulative expenditures are reported, indicating the total cost per recruitment method. The inset shows the breakdown for each type of newspaper advertisement.

Chi-square showed a difference in rates of families recruited for direct mail, newspaper advertisements, and posters and brochures (X2 = 5.88, p = 0.053). The percentage of families recruited from direct mail, newspaper advertisements, posters and brochures, and other sources are 67.5%, 24.3%, 2.9%, and 7.1%, respectively. Of the recruited minorities, 47.1% were obtained by direct mailing, 35.3% through newspaper advertisements (1 participant through minority-specific newspaper), 11.8% through other sources, and 5.9% through posters and brochures.

Figure 3 shows cumulative costs to recruit successive participants. The initial cost to recruit the first participant was nearly identical for direct mailing and newspaper advertisements. The slope of the cumulative curve is steeper for newspaper advertisements than direct mailings. Costs per recruited family increased at a more rapid rate for newspaper advertisements than with direct mailings.

Discussion

The results indicate that direct mailing was the most cost-effective method to recruit families for an obesity prevention trial to reduce television watching in young children, which supports the growing literature on effectiveness of direct mailing (Bjornson-Benson et al., 1993; Borhani, Tonascia, Schlundt, Prineas, & Jefferys, 1989; Connett, Bjornson-Benson, & Daniels, 1993; Gerace, George, & Arango, 1995; Rudick, Anthonisen, & Manfreda, 1993). A combination of direct mailing and newspapers was most successful for minority recruitment, supporting the research that using several methods increases recruitment effectiveness (Bjornson-Benson et al., 1993; Swanson & Ward, 1995).

The initial investment was greatest for posters and brochures, with similar total costs for direct mailing and newspaper advertisements. Direct mailing yielded 65.7% of families at the lowest cost per family ($227.76), while newspaper advertisements yielded 24.3% of families at a cost of $546.95 per family. The cumulative graphs show that newspaper advertisements became less effective over time than direct mailings. This can be due to the fact that repeated advertisements were distributed to the same regional population, while direct mailings reached a new sample with each mailing. Posters and brochures were distributed to over 150 community settings, but the small 2.9% return does not seem to justify the costs incurred.

Word of mouth required negligible recruitment costs, and was associated with a small number of recruited families. Given the minimal cost, it would be interesting to explore methods to improve on the utility of word of mouth, such as creating local networks of involved participants. More systematic and active referrals of friends and families can potentially increase the number of individuals recruited.

Alternative methods of recruitment include the enrollment of participants through registries and the Internet. Computer technology has made it possible to develop large databases of potential participants that can be used to inform doctors and patients of available clinical trials. Alternatively, government or private registries can be used by recruiters to identify potential participants (Newcomb, Love, Phillips, & Buckmaster, 1990). The Internet represents a method for reaching large numbers of people, but it poses challenges. Many people ignore unsolicited emails, which may be why a recent study using email as an advertisement tool resulted in a 0% response rate (Koo & Skinner, 2005). Computer use may not be equal across demographic groups, possibly creating biased samples (Etter & Perneger, 2001; Scholle et al., 2000). Finally, Internet recruitment may not be an effective tool for studies recruiting locally, since it may be harder to target a specific geographic area (Seaton, Cornell, Wilhelmsen, & Vieten, 2004). The Internet may be more successful when used in conjunction with traditional recruitment methods. Posters, fliers, and newspaper advertisements could include website addresses for accessing additional information about studies.

One factor that may limit the generalizability of the results is differences in costs for varied regions, such as hourly wages. Another limiting factor is location. Perceived safety, local traffic patterns, driving distance, or ease of transportation to the research site may limit generalizability. For example, in some urban areas, public transportation is a major method of travel, and it is possible that as access to public transportation decreases, recruitment rates would also decrease. In this study, zip codes closest to the University were used first, with subsequent mailings being further from the University. Equal numbers of families were recruited with each mailing, which suggests effectiveness remained the same with each mailing.

Exposure to multiple sources, including exposure to different (multiple exposure) or to the same (repeated exposure) source over time was not tracked and could impact results. Exposure to multiple sources could inflate the effectiveness of a method, such as receiving a direct mailing after viewing a newspaper advertisement. Repeated exposure could increase the yield by prompting someone to seek additional study information, or could decrease the yield over time, as readers adapt to multiple newspaper advertisements. Finally, the way in which a recruitment strategy is implemented can affect the yield. For example, placing posters and brochures in heavily trafficked areas, such as malls, may boost recruitment. Using one mass mailing rather than smaller, repeated mailings can recruit larger samples in a shorter amount of time.

Efficient and cost-effective recruitment is a critical component of research programs. This study has led our research group to increase our utilization of direct mailings to recruit families. Additional research is needed to compare methods using experimental designs. For example, randomly assigning different areas of town to different recruitment approaches could be used to compare methods or the effectiveness of the dose of a method. Recruitment of a diverse population is needed in many studies to maximize generalizability of the results, and research is needed to test the best way to tailor recruitment strategies for specific ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Recruitment is a major component of studies, and the failure to recruit a large and representative sample can influence study implementation and generalizability of results. This study showed the superior cost-effectiveness of direct mailing compared to newspaper advertisements and posters and brochures. Research is needed to develop innovative methods for recruiting participants for clinical trials, and to compare the cost-effectiveness of methods to provide the most effective set of tools for study implementation.

Figure 1.

Total recruitment costs (top graph) and total costs by recruitment method (bottom graph) in Western New York (February, 2003 - November, 2004). Each bar represents a different recruitment method divided into cost of materials, staff time, and media expense.

Acknowledgements

JNR and LHE contributed to the study design; JLR and LHE assumed responsibility for drafting and revising the manuscript; JHF and DDW were involved in the data collection and contributed to the Methods section of the manuscript; SJS contributed to the Introduction and Discussion sections of the manuscript. LHE is a consultant to Kraft foods. None of the other authors had any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This research was supported by grant DK63442 awarded to Dr. Epstein from the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bjornson-Benson WM, Stibolt TB, Manske KA, Zavela KJ, Youtsey DJ, Buist AS. Monitoring recruitment effectiveness and cost in a clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14:52S–67S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhani NO, Tonascia J, Schlundt DG, Prineas RJ, Jefferys JL. Recruitment in the Hypertension Prevention trial. Hypertension Prevention Trial Research Group. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1989;10:30S–39S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connett JE, Bjornson-Benson WM, Daniels K. Recruitment of participants in the Lung Health Study, II: Assessment of recruiting strategies. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14:38S–51S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Perneger TV. A comparison of cigarette smokers recruited through the Internet or by mail. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:521–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace TA, George VA, Arango IG. Response rates to six recruitment mailing formats and two messages about a nutrition program for women 50-79 years old. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1995;16:422–431. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd P, Parshall M, Wojcik S, Struttmann T. Overcoming recruitment challenges in construction safety intervention research. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2004;45:297–304. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan M, Phillips K, Fair JM, King AC. Using direct mail to recruit Hispanic adults into a dietary intervention: an experimental study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22:89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02895172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo M, Skinner H. Challenges of internet recruitment: a case study with disappointing results. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7:e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and Health Statistics. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenkron JC, Farquhar JW. Recruitment using mass media strategies. Circulation. 1982;66:IV32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Emmons KM, Klar N, Fava JL, LaForge RG, Abrams DB. Challenges to improving the impact of worksite cancer prevention programs: comparing reach, enrollment, and attrition using active versus passive recruitment strategies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:157–166. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh S, Ossip-Klein DJ, Spada J, Burton K. Recruitment strategies and success in a multi-county smoking cessation study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2000;2:281–284. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb PA, Love RR, Phillips JL, Buckmaster BJ. Using a population-based cancer registry for recruitment in a pilot cancer control study. Preventive Medicine. 1990;19:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RR, Fujimoto WY, Marrero DG, Brenneman T, Charleston JB, Edelstein SL, et al. The Diabetes Prevention Program: recruitment methods and results. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2002;23:157–171. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudick C, Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J. Recruiting healthy participants for a large clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14:68S–79S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholle SH, Peele PB, Kelleher KJ, Frank E, Jansen-McWilliams L, Kupfer D. Effect of different recruitment sources on the composition of a bipolar disorder case registry. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35(5):220–277. doi: 10.1007/s001270050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton KL, Cornell JL, Wilhelmsen KC, Vieten C. Effective strategies for recruiting families ascertained through alcoholic probands. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:78–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000107200.88229.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SYSTAT . SYSTAT for Windows (Version 11.0) SYSTAT Software, Inc.; Richmond, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]