Abstract

A shift of the angiogenic balance to the proangiogenic state, termed the “angiogenic switch,” is a hallmark of cancer progression. Here we devise a strategy for identifying genetic participants of the angiogenic switch based on inverse regulation of genes in human endothelial cells in response to key endogenous pro- and antiangiogenic proteins. This approach reveals a global network pattern for vascular homeostasis connecting known angiogenesis-related genes with previously unknown signaling components. We also demonstrate that the angiogenic switch is governed by simultaneous regulations of multiple genes organized as transcriptional circuitries. In pancreatic cancer patients, we validate the transcriptome-derived switch of the identified “angiogenic network:” The angiogenic state in chronic pancreatitis specimens is intermediate between the normal (angiogenesis off) and neoplastic (angiogenesis on) condition, suggesting that aberrant proangiogenic environment contributes to the increased cancer risk in patients with chronic pancreatitis. In knockout experiments in mice, we show that the targeted removal of a hub node (peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor δ) of the angiogenic network markedly impairs angiogenesis and tumor growth. Further, in tumor patients, we show that peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor δ expression levels are correlated with advanced pathological tumor stage, increased risk for tumor recurrence, and distant metastasis. Our results therefore also may contribute to the rational design of antiangiogenic cancer agents; whereas “narrow” targeted cancer drugs may fail to shift the robust angiogenic regulatory network toward antiangiogenesis, the network may be more vulnerable to multiple or broad-spectrum inhibitors or to the targeted removal of the identified angiogenic “hub” nodes.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cancer therapy, homeostatic balance, systems biology, pancreatic carcinoma

Angiogenesis is a physiologic process that encompasses the growth of capillary blood vessels (1–3). There is increasing evidence that the disturbance of the homeostatic balance of pro- and antiangiogenic factors contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous disorders (1–3). A shift of the angiogenic balance to the proangiogenic state, termed the “angiogenic switch,” is considered a hallmark of cancer progression, invasiveness, and metastasis (1, 3). Human tumors arise in the absence of angiogenic activity and may exist in a microscopic dormant state for months to years without neovascularization (4, 5). The switch to the angiogenic phenotype permits presymptomatic microscopic-sized dormant cancers to become rapidly growing tumors that can subsequently metastasize (6, 7). Although certain fundamental concepts and several key components of the angiogenesis process and the angiogenic switch have been reported (1–3), the underlying genetics are not completely known.

We sought to investigate the molecular and genetic mechanisms mediating the switch to the angiogenic phenotype. To this end, we propose the hypothesis that, for a given homeostatic system, those genes that are inversely regulated after negative and positive system perturbation are strong candidates for significant regulatory involvement in the system. For angiogenesis, the system perturbation is achieved by the key endogenous angiogenesis regulatory proteins targeting endothelial cells as the effector cells. We further hypothesized that among the inversely regulated genes, those up-regulated by proangiogenic proteins and down-regulated by antiangiogenic proteins are participants in proangiogenic signaling, whereas those genes up-regulated by antiangiogenic and down-regulated by proangiogenic proteins participate in antiangiogenic signaling.

To test this concept, human microvascular endothelial cells were treated with endostatin, a potent but nontoxic endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, and alternatively with VEGF and/or basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), both potent angiogenesis stimulators. The human transcriptome was analyzed by cDNA arrays to observe how gene expression across the genome was altered by the resulting shifts of the angiogenic balance. This strategy led to the discovery that a sizable fraction of the genome participates in the angiogenesis process. A subsequent network analysis of the classified genes confirmed that our strategy preserved the gene regulatory network defining the unabridged genomic shift of the angiogenic balance to a proangiogenic state, the angiogenic switch.

The viability of the predicted in vitro angiogenic network signature was further studied in vivo by analyzing human tissue samples ranging from normal pancreas (NP) to chronic inflammation [chronic pancreatitis (CP)] to pancreatic carcinoma and metastatic disease. Thus, we correlated the clinical and histopathological switch to the angiogenic phenotype during the development of human pancreatic carcinoma with the shift of the gene signature of our predicted angiogenic network. The robustness of the proposed angiogenic network was further tested by the targeted removal of an identified “hub node”, peroxisome proliferative activated receptor δ (PPARδ), in the tumor microenvironment by using PPARδ−/− mice.

We suggest that classifying genes by their regulation status after endothelial cell treatment with pro- and antiangiogenic factors is a useful method for defining critical components in angiogenesis signaling. Beyond an improved comprehension of the genetic cooperation underlying the angiogenic switch in tumors, the emerging topological features of the angiogenic network provide insights to the robustness of the angiogenesis process and elucidate promising targets for the antiangiogenic cancer therapy.

Results

Elucidation of Genetic Participants in the Angiogenic Switch.

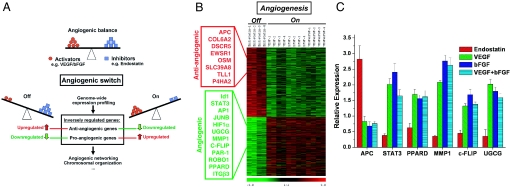

To analyze the global gene expression signature induced by endogenous pro- and antiangiogenic factors, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells isolated from two different human donors were treated for 4 h with (i) VEGF (10 ng/ml), (ii) bFGF (20 ng/ml), (iii) combined VEGF (10 ng/ml) plus bFGF (20 ng/ml) (denoted as VEGF+bFGF), and (iv) endostatin (200 ng/ml). The VEGF and bFGF treatments mimicked the shift of the angiogenic balance to the proangiogenic state, whereas the antiangiogenic state in endothelium was mimicked by the endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin (workflow, Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Genetic participants of the angiogenic switch. (A) We hypothesized that global analysis of transcriptional perturbation induced by positive and negative regulators of angiogenic balance may provide a rational algorithm to define the genetic participants of the angiogenic switch. Human microvascular endothelial cells were treated for 4 h with the endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin (200 ng/ml) to mimic the shift of the angiogenic balance toward an antiangiogenic (Off) state. Conversely, the proangiogenic (On) state in endothelium was emulated by using proangiogenic stimulators VEGF (10 ng/ml), bFGF (20 ng/ml), or combined VEGF (10 ng/ml) and bFGF (20 ng/ml). The inverse-regulation pattern of genes after pro- and antiangiogenic treatment was used as the selection criteria to predict the genes involvement in the angiogenic process. (B) Using significance analysis of microarrays, 2,370 transcripts with significant inverse-expression patterns were selected (P < 0.01). From these 2,370 transcripts, 1,140 were down-regulated after endostatin treatment and up-regulated after VEGF/bFGF treatment (categorized to participate in proangiogenic signaling, example genes in green box), whereas the remaining 1,230 transcripts were oppositely regulated (categorized to participate in antiangiogenic signaling, red box; see also SI Text). Each row represents log2 expression ratios of an individual gene (see color code) and the columns indicate each respective treatment (in quadruplicates, 1–4). (C) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR confirmation of inverse regulation of six selected example genes in endothelial cells after endostatin vs. VEGF/bFGF treatment. Bars are means ± SD from three independent measurements and show relative expression levels compared with untreated control (P < 0.01).

After isolation of total RNA, genome-wide expression profiling was performed by using a Human Unigene II c-DNA array covering >90% of the genome. The resulting expression data were analyzed by using supervised and unsupervised clustering algorithms. The predominantly observed expression patterns were clusters of coexpressed genes that were “inversely regulated” after pro- vs. antiangiogenic treatment. All clustering methods applied, including hierarchical clustering, K-means, and self-organizing maps as well as principal component analysis, clearly distinguished between the proangiogenic (VEGF, bFGF, or VEGF+bFGF) and the antiangiogenic (endostatin) signatures (data not shown). These data supported our concept that the transcriptional regulation of many genes involved in balanced “homeostatic” processes such as angiogenesis were in alignment with the direction of the systems perturbation (Fig. 1).

Selection of the Gene Assembly Involved in Angiogenesis.

Based on the clustering results, we selected the statistically most significantly inversely regulated genes from the microarray data. Using significance analysis of microarrays, 2,370 transcripts were significantly inversely regulated in endothelium after defined pro- and antiangiogenic treatments. These transcripts provided the candidate genes for angiogenic signaling (false discovery rate ≤1%; Fig. 1B). From these transcripts, 1,230 (≈600 unique genes with locus link ID) were significantly up-regulated after treatment with endostatin and simultaneously down-regulated after treatment with VEGF, bFGF, and VEGF+bFGF (P < 0.01) and were thus categorized as participants in antiangiogenic signaling. Conversely, 1,140 transcripts (≈550 unique genes with locus link ID) down-regulated after endostatin treatment were found to be up-regulated after VEGF, bFGF, and VEGF+bFGF treatment and were categorized as participants in proangiogenic signaling. For independent confirmation of array results, the expression patterns of six selected genes were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). The gene selection was based on critical involvement within the angiogenic network [hub nodes: PPARδ, STAT3, MMP1, and FLICE-like inhibitory protein (c-FLIP)] or interesting submodule [apoptosis and resistance, cFLIP, and UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG); see below].

Interestingly, among the many genes with putative angiogenic function, the adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) gene was classified as antiangiogenic, whereas PPARδ, STAT3, MMP1, c-FLIP, and UGCG were classified as proangiogenic. For a list of antiangiogenic genes, see also supporting information (SI) Text.

Identification of an Angiogenesis Gene Regulatory Network.

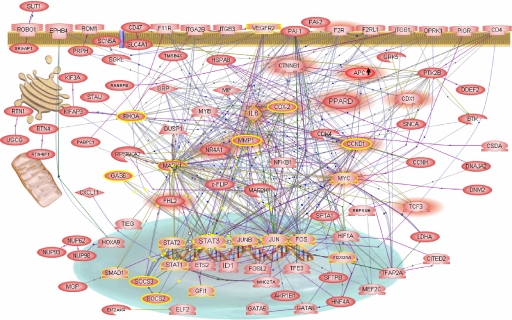

To investigate whether the inversely regulated genes in endothelium are interlinked within a broader “signaling network,” we analyzed the selected putative proangiogenic genes. We then constructed a genetic network representing the shift of the angiogenic balance to the proangiogenic state in endothelial cells (Fig. 2; see also SI Fig. 5); in the initial step of the construction, we searched and analyzed direct interactions between the inversely regulated genes by using information extracted from the published experimental literature and from the entire National Center for Biotechnology Information–PubMed database. Thus we established a large number of direct connections between genes and respective proteins. This set of interactions also defined the cellular potential for the assembly of protein complexes, signaling, and effector pathways. By positioning the expression data onto known experimentally verified physical interactions, we restricted all possible associations between the regulated genes from our microarray expression data to those that are considered to be physically possible in the cell. This approach led to the generation of condition-specific functional “signature networks,” which comprised sets of functional pathways organized into a metanetwork. Because the interpretation of the generated network depends on the context, here angiogenesis, with genes chosen for putative proangiogenic function, the resulting network likely represents the shift of the angiogenic balance to a specific condition, namely the proangiogenic state in endothelial cells.

Fig. 2.

Angiogenic signaling network. A gene regulatory network constructed from inversely regulated proangiogenic genes. All presented genes are down-regulated after endostatin although up-regulated after VEGF/bFGF treatment (except APC gene; arrow demonstrates opposite regulation). The direction of gene regulation and the high degree of cooperative networking between the selected genes point to a switchable angiogenic network. The concerted up-regulation of the network genes indicates the proangiogenic state (On). Highlighted are gene interactions based on promotor-binding site (green connection lines), protein modification (yellow connection lines), protein–protein binding (violet connection lines), gene expression (blue connection lines), and gene regulation (black connection lines). Two signaling pathways, STAT3 (yellow circles) and PPARδ/β-catenin (red shadows), are highlighted and demonstrate the interconnectedness of the pathways within the angiogenic network.

Several well known key components of the angiogenic response are represented in the network, including HIF1-α and Id1 transcription factors, VEGF receptor 2, β3 integrin, plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAI1/2), thrombin receptor (F2R), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). At the same time, genes only recently tied to the angiogenic response are visualized, thus affirming the predictive power of our approach. Examples include ROBO1/SLIT1, STATs, and the Ap1 transcription factors c-Jun, c-Fos, and JunB (8, 9). Genes not known to be connected to angiogenesis, e.g., PPARδ, CTNNB1, IL6, CCND1, c-FLIP, UGCG, and MMP1 are also represented in large numbers. This suggests a broader genetic participation in angiogenesis than previously thought and highly interactive pathways thought to be distinct.

Angiogenic Switch in Human Pancreatic Carcinoma in Vivo.

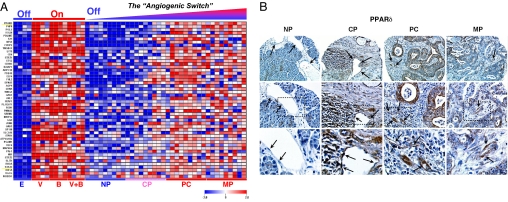

We asked whether the angiogenic gene signature in endothelial cells would predict a shift of the angiogenic balance in humans in vivo. Human pancreatic specimens from 36 individuals who had undergone surgery in our hospital were studied. Tissue samples were obtained from patients with a putative gradient of angiogenesis; we analyzed nine patients with NP, nine patients with CP, nine patients with pancreatic cancer (PC), and nine patients with metastatic PC (MP). Intriguingly, the comparison of the in vitro derived “angiogenic signature” with the genetic signatures from the patient samples showed a gradient of up-regulation of the expression of angiogenesis genes from normal pancreatic tissue to chronically inflamed tissue, to PC (Fig. 3A). This observed gradient in gain of proangiogenic function of the inversely regulated genes thus paralleled the phenotypic demonstration of enhanced angiogenesis in cancer tissue (10, 11).

Fig. 3.

Angiogenic switch in human PC. (A) In vivo expression profiles from pancreatic tissue in correlation to the in vitro data on the angiogenic switch after endostatin (E), VEGF (V), bFGF (B), and VEGF+bFGF (V+B). Included in the analysis are nine samples from human NP, nine samples from patients with CP, nine samples from patients with PC, and nine samples from patients with MP. In accordance with in vitro data, the predicted proangiogenic genes are increasingly up-regulated from normal (angiogenesis Off) to chronic inflammation to cancer (angiogenesis On). This provides genetic evidence for the angiogenic switch in human tumors. Expression ratios are colored according to the scale bar: Blue, >2-fold down-regulation; red, >2-fold up-regulation. (B) The expression levels of PPARδ protein are confirmed in human pancreatic specimens by using immunohistochemistry on high-density tissue microarrays. PPARδ staining intensity is enhanced in CP, PC, and MP compared with NP. The up-regulation of PPARδ is not restricted to, but is actually more enhanced in the tumor vasculature and in the tumor stroma. The black arrows point to the endothelial cells. (Top) ×200, (Middle) ×400; Bottom highlights the endothelial cells magnified from the square box within the ×400 view.

PPARδ Regulation on High-Density Human Pancreatic Tissue Microarrays.

To confirm the signature data on the protein level, we determined the protein expression of a putatively important proangiogenic “hub node” gene, PPARδ, in human tissue in vivo (12–14). The immunohistochemistry on high-density tissue microarrays of NP, CP, PC, and metastasis specimens closely paralleled the expression profiling data on PPARδ regulation (Fig. 3B). In particular, PPARδ staining intensity increased with increasing grade of the proangiogenic microenvironment as we sampled successively from NP, to CP, to PC and metastasis. The up-regulation of PPARδ was more pronounced in the tumor vasculature and in the tumor stroma, e.g., in fibroblasts, although this up-regulation was not restricted to these sites (Fig. 3B).

Critical Involvement of PPARδ in Angiogenesis and Tumor Microenvironment.

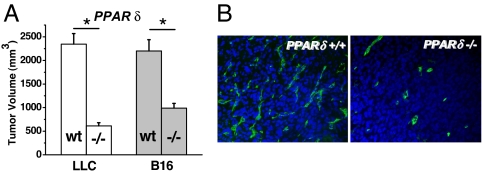

Our array data also indicated that the APC/β-catenin/PPARδ tumor suppressor pathway (12–14) constituted a potentially critical pathway in the “angiogenic network.” Several components of this pathway were found to be inversely regulated after pro- and antiangiogenic treatment. APC, a negative upstream regulator of β-catenin (CTNNB1), was classified as antiangiogenic (Fig. 1 D and E). Simultaneously, β-catenin and its downstream targets (Cyclin D1, MYC, and PPARδ) were classified as proangiogenic in endothelium (Fig. 2). Thus, the direction of gene regulation was in alignment with the tumor suppressor function that has been proposed for this pathway. In particular, the array data suggested a proangionenic role for PPARδ. To further explore the function of PPARδ in angiogenesis and in the tumor microenvironment, we performed tumor growth experiments in PPARδ knockout (PPARδ−/−) vs. WT Bl6 mice (PPARδ+/+) by using Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) and B16 melanoma s.c. tumor models. In this setting, PPARδ signaling was silenced in the entire mouse, including tumor stroma, and in tumor vessels recruited from the host but not in LLC or B16 melanoma tumor cells. Strikingly, we found that both tumor angiogenesis as measured by CD31 vessel count as well as tumor growth were markedly inhibited in PPARδ−/− vs. WT mice (P < 0.01, Fig. 4 A and B) in both tumor models. These knockout data suggested a strong proangiogenic effect of PPARδ in the murine tumor microenvironment and confirmed the proangiogenic classification of PPARδ in human endothelium in vitro and the results in human pancreas in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Critical involvement of PPARδ in angiogenic process. PPARδ silencing in the tumor microenvironment inhibits tumor growth (A) and reduces tumor microvascular density (B) in LLC and B16 melanoma, two syngeneic tumors growing s.c. in WT (wt) and PPARδ (−/−) mice. A shows tumor volumes assessed 20 (LLC) and 29 (B16) days after s.c. tumor injection. Bars are mean ± SD (*, P < 0.01 in −/− vs. WT). (B) Reduced vascular density in −/− mice is demonstrated in LLC tumors (view, ×200) by CD31 (green, Alexa488, tumor vascular endothelium) and nuclear (blue, DAPI) costaining.

Correlation of PPARδ Expression with Pathological and Clinical Parameters.

To further validate the role of PPARδ in angiogenesis and tumor growth, we correlated the differential expression of PPARδ mRNA in published large-scale cancer microarray data with the respective reported pathological and clinical endpoints. The statistical analyses in all data sets and all tumor types studied, including prostate cancer, breast cancer, and endometrial adenocarcinoma, showed that PPARδ expressions were enhanced compared with the corresponding normal tissues (SI Fig. 6). Furthermore, elevated PPARδ expression levels were also highly correlated with advanced stages of tumor progression and with increased risk for tumor recurrence or distant metastasis (SI Fig. 6). Together, the analysis of clinical data suggests an important role of PPARδ in angiogenesis, tumor formation, and tumor invasiveness.

Discussion

Here we report principles that govern the switch to the angiogenic phenotype in vitro and in human PC in vivo. These principles depend on our finding that a set of angiogenesis regulatory genes cooperate in large networks to effect the angiogenic switch. Further, we introduce a strategy to identify genes that participate in these networks based on the inverse regulation of genes by endogenous pro- and antiangiogenic proteins. We speculate that this principle of inverse regulation, alignment of gene regulation in the direction of treatment, may be useful in identifying the genetic participants of other homeostatic processes.

A crucial step in the validation of the proposed angiogenic network in vivo was to investigate the status of the angiogenic switch as it depends on disease course in human pancreatic tissues. Array analysis in 36 human individuals revealed increased expression of the predicted angiogenic genes from NP to CP, to PC tissue samples. This activation of proangiogenic genes in human samples thus paralleled the phenotypic observation of enhanced angiogenesis in tumors. That the proangiogenic state in CP is intermediate between that of the normal and cancerous condition could be interpreted in terms of the neovascularization induced by inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, which then continue to arrive at the inflammatory site by the “conduit” of new blood vessels (15). Alternatively, this finding may indicate that a “proangiogenic” stromal microenvironment “prepares” a specific tissue for the future development of cancer (11, 16, 17). Accordingly, an up to 19-fold increased risk of PC has been described in patients with CP (18). Taken together, our findings thus provide genetic evidence for the concept of the angiogenic switch as a hallmark of cancer development and suggest a key role for an aberrant proangiogenic microenvironment in the multistep cancer development process. In line with our functional assignment, a key gene of the angiogenic network, MMP1, has recently been identified as a putative breast cancer-predictive marker expressed most intensely in tumor stroma (19). The most significant finding in that report was the correlation of MMP1 expression with the probability of a premalignant breast lesion developing into an invasive breast cancer (19). These findings corroborate the proposed role of the angiogenic switch in the transition of a premalignant lesion into an invasive malignant tumor (3, 8).

The existence of few hubs and many low-degree nodes is characteristic for “scale-free” networks making these networks robust against random perturbation (20–22). On the other hand, such networks are highly vulnerable to targeted removal of any of their hubs. Our data clearly confirm this therapeutic concept by demonstrating that the targeted removal of an identified hub node (PPARδ) of the angiogenic network drastically impairs angiogenesis in vivo. Of note, recent experiments with genetically predisposed mice (APCmin) had resulted in conflicting data concerning the tumor promoting vs. the preventing effects of PPARδ and its involvement downstream of the APC-β-catenin pathway (12, 23–26). Using B16 melanoma and LLC tumor models, we provide here genetic evidence that silencing of PPARδ in the tumor microenvironment impairs tumor growth and angiogenesis. Our findings with reduced tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth seen in PPARδ−/− mice are consistent with reports demonstrating impaired wound healing and reduced body fat, both angiogenesis-dependent processes (27, 28). Our data also indicate that phenotypic outcome of a certain genetic alteration is context-dependent. Although PPARδ silencing in tumor cells or in precancerous tissue (e.g., APCmin mice, “oncogenic background”) may be able to promote or inhibit, respectively, the tumorigenesis process (12, 23–26), we show here that targeted inhibition of the microenvironment impaired tumor growth.

The viability of our strategy to correctly predict angiogenic network components was also independently assessed by statistical analyses of PPARδ expression in published large-scale microarray data from cancer patients. PPARδ expression levels were found to be significantly increased in prostate, breast, and endometrial adenocarcinoma and were highly correlated with advanced pathological tumor stage and increased risk for tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. Together with our own data in inflammatory and cancerous pancreatic tissue, these clinical data support the notion of an integral role for PPARδ signaling in angiogenesis, inflammation, and cancer and thus may reinforce the validation of other predicted angiogenic network genes.

It has been suggested for biological networks that various types of cellular functionality are effected by a relatively small number of tightly connected genes or hub nodes. Furthermore, these hubs are shared among different biological processes (29, 30). For example, the angiogenesis process involves a number of steps that are tightly controlled temporally and spatially. These include the expression of proteases to digest the basement membrane, allowing endothelial cells to invade the surrounding tissue, subsequent endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and finally differentiation of endothelial cells to form a sprout. Likewise, malignant tumor cells are characterized by abnormal proliferation, invasion and dedifferentiation capabilities. Thus, it is conceivable that these two processes, namely tumorigenesis and angiogenesis, share a number of cellular subfunctions. This could explain our findings that a number of tumor suppressor (e.g., APC) and oncogenic pathways (e.g., MYC, STATs, and WNT) participate in angiogenic signaling (Fig. 2). Moreover, our data also suggest that genes known to be involved in axonal guidance and neurogenesis such as Ephrins and the ROBO/SLIT pathway participate in angiogenesis signaling. Thus, an important realization from our transcriptome and genetic networking analysis is that pathways considered to be distinct may show cross-connections. In support of this view, a direct link between the tumor suppressor gene p53 and endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors was recently reported (31, 32).

From the cancer therapy perspective, an important consequence of the identification of an angiogenic network is that the inhibition of a single node or subpathway may not severely affect its functionality. The robustness against random attacks has been shown for other error-tolerant biological networks, including the metabolome and the proteome in yeast and Drosophila (33–35). Therefore, the failure of some single-agent antiangiogenic monotherapies in cancer patients may conceivably be associated with compensatory mechanisms arising from the topology of an angiogenesis network (1, 2, 36, 37). In fact, clinically, in cancer patients, the escape from single-pathway inhibition has been shown for several pathways. For example, the inhibition of VEGF signaling can result in the subsequent up-regulation of two other proangiogenic pathways, namely bFGF and placental growth factor (38, 39). Similarly, the inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling can induce up-regulated VEGF angiogenic signaling (40, 41). Finally, genetic silencing of integrin β3 or hypoxia-inducible factor-1 pathways resulted in enhanced expression levels of VEGF receptor-2 and IL-8, respectively (42–44).

Thus, the identification of an angiogenic network may result in suggestions for the rational design of antiangiogenic cancer agents, back from narrow targeted single agents to multiple or broad spectrum inhibitors able to inhibit several hub nodes necessary to shift the angiogenic network toward the antiangiogenic state (1, 45–51). It is conceivable that the simultaneous targeting of several critical angiogenic network genes might be the most promising antiangiogenic strategy. Moreover, the cross-connections suggested here among pathways such as angiogenesis and apoptosis may explain in part the collateral benefits of combination cancer therapies consisting of antiangiogenics. For example, we found that UGCG and C-FLIP are up-regulated by VEGF and bFGF but down-regulated by endostatin. UGCG has been shown to confer resistance to ceramid-induced apoptosis and plays a role in multidrug resistance (52, 53). Likewise, c-FLIP has been shown to inhibit death ligands and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in different tumors (54–56). Integration of the c-FLIP and UGCG in the angiogenic network thus links the three processes of tumor angiogenesis, impaired apoptosis signaling, and therapeutic resistance, providing a strong molecular rationale for the utility of combination therapies exploiting angiogenesis inhibitors (46, 49, 50). Indeed, the first Food and Drug Administration-approved antiangiogenic drug, bevacizumab (Avastin), an antibody against VEGF, although not markedly effective as monotherapy, has shown significant clinical activity against metastatic colorectal cancer, particularly in combination with chemotherapy (57).

Although at this time it is unclear whether the deciphered angiogenic network signature can predict the probability of a premalignant lesion developing into invasive cancer, this may provide attractive therapeutic targets aimed at preventing the transition of the small dormant cancer foci into an aggressive lethal cancer. Further, in cases where the cancer is already clinically relevant, an improved understanding of the genetic networking and the identification of critical pathway components involved in the “angiogenic switch” can be important for both the identification of new potential therapeutic targets and the improvement of the efficacy of known therapeutic modalities (64).

Methods

Reagents, Cell Culture, Tissue Samples, and RNA Isolation.

Primary isolated human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMVEC) from two different human donors were used as described (8, 46, 49–). For expression profiling and RT-PCR assessments, cells were treated with endostatin or VEGF and/or bFGF (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany). Mouse LLC and B16 melanoma tumor cell lines (Tumorbank DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany) were maintained at standard conditions.

All studies were approved by the ethics committees of the University of Bern (Bern, Switzerland) and the University of Heidelberg, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Human tissue samples and RNA were processed as described (58). Total RNA from HDMVEC was isolated by using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For details see SI Text.

Expression Profiling and Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR.

Genome-wide expression profiling of cultured cells was performed by using 75,000 human transcripts (74,834 spotted c-DNA clones on three subarrays) (8). The pancreatic tissue samples were profiled on Affymetrix GeneChip HumanGenome U95Av2 Array (HG-U95Av2) (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), as described (59–61). Expression levels of RNA transcripts were quantitated by real-time PCR, as described (8, 49, 62). For details, see SI Text.

High-Density Tissue Microarrays.

For the analysis of human pancreatic samples, tissue microarrays were produced by using a manual tissue arrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI). In total, 37 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PC), 17 lymph node, and 8 distant (liver or peritoneum) metastasis (MP), 8 CP, and 10 NP samples were investigated. For details, see SI Text.

Animal Studies and Statistical Analysis.

The animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the German Animal Protection Law and were approved by the state agency supervising animal experimentation (Regierungspraesidium, Karlsruhe, Germany). PPARδ knockout (PPARδ−/−), and WT mice were generated as described (28). LLC and B16 melanoma (B16) tumor cells were injected s.c. into the hind limb (5 × 106 cells in 100 μl of PBS) of PPARδ−/− and WT mice. Tumor growth was assessed by calipers. Microvascular density and nuclear staining were assessed by immunohistological analyses.

For multiple comparisons, the Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was used for nonparametric variables. For parametric variables, ANOVA was used along with Fisher's least-significant difference. All analyses were two-tailed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For details, see SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Krebshilfe Grant 106997, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft National Research Program Tumor–Vessel Interface Grant SPP1190, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)/NASA Specialized Center of Research Grant NNJ04HJ12G, and the Tumorzentrum Heidelberg–Mannheim.

Abbreviations

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- PPARδ

peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor δ

- UGCG

UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase

- APC

adenomatosis polyposis coli

- NP

normal pancreas

- CP

chronic pancreatitis

- PC

pancreatic cancer

- MP

metastatic PC

- LLC

Lewis lung carcinoma.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the Array Express database, www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress (accession nos. E-EMBL-6, E-RZPD-14E-RZPD-15–16, and E-RZPD-20).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705505104/DC1.

References

- 1.Abdollahi A, Hlatky L, Huber PE. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Cell. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folkman J, Kalluri R. Nature. 2004;427:787. doi: 10.1038/427787a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naumov GN, Bender E, Zurakowski D, Kang SY, Sampson D, Flynn E, Watnick RS, Straume O, Akslen LA, Folkman J, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:316–325. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman J, Kalluri R. Nature. 2004;427:787. doi: 10.1038/427787a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naumov GN, Bender E, Zurakowski D, Kang SY, Sampson D, Flynn E, Watnick RS, Straume O, Akslen LA, Folkman J, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:316–325. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdollahi A, Hahnfeldt P, Maercker C, Grone HJ, Debus J, Ansorge W, Folkman J, Hlatky L, Huber PE. Mol Cell. 2004;13:649–663. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, et al. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce JA. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He TC, Chan TA, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cell. 1999;99:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Nat Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folkman J. In: Targeted Therapies in Rheumatology. Smolen JS, Lipsky PE, editors. London: Martin Dunitz; 2003. pp. 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissell MJ, Labarge MA. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malka D, Hammel P, Maire F, Rufat P, Madeira I, Pessione F, Levy P, Ruszniewski P. Gut. 2002;51:849–852. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poola I, DeWitty RL, Marshalleck JJ, Bhatnagar R, Abraham J, Leffall LD. Nat Med. 2005;11:481–483. doi: 10.1038/nm1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Nature. 2000;406:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giot L, Bader JS, Brouwer C, Chaudhuri A, Kuang B, Li Y, Hao YL, Ooi CE, Godwin B, Vitols E, et al. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta RA, Wang D, Katkuri S, Wang H, Dey SK, DuBois RN. Nat Med. 2004;10:245–247. doi: 10.1038/nm993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harman FS, Nicol CJ, Marin HE, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Nat Med. 2004;10:481–483. doi: 10.1038/nm1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park BH, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2598–2603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051630998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed KR, Sansom OJ, Hayes AJ, Gescher AJ, Winton DJ, Peters JM, Clarke AR. Oncogene. 2004;23:8992–8996. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michalik L, Desvergne B, Tan NS, Basu-Modak S, Escher P, Rieusset J, Peters JM, Kaya G, Gonzalez FJ, Zakany J, et al. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:799–814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters JM, Lee SS, Li W, Ward JM, Gavrilova O, Everett C, Reitman ML, Hudson LD, Gonzalez FJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5119–5128. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5119-5128.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. Nature. 2000;407:651–654. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Robert F, Odom DT, Bar-Joseph Z, Gerber GK, Hannett NM, Harbison CT, Thompson CM, Simon I, et al. Science. 2002;298:799–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folkman J. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:e35. doi: 10.1126/stke.3542006pe35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teodoro JG, Parker AE, Zhu X, Green MR. Science. 2006;313:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1126391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Nature. 2000;406:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giot L, Bader JS, Brouwer C, Chaudhuri A, Kuang B, Li Y, Hao YL, Ooi CE, Godwin B, Vitols E, et al. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain RK, Duda DG, Clark JW, Loeffler JS. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:24–40. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willett CG, Boucher Y, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Munn LL, Tong RT, Kozin SV, Petit L, Jain RK, Chung DC, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8136–8139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casanovas O, Hicklin DJ, Bergers G, Hanahan D. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viloria-Petit AM, Kerbel RS. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:914–926. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bianco R, Troiani T, Tortora G, Ciardiello F. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;1(12 Suppl):S159–S171. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizukami Y, Jo WS, Duerr EM, Gala M, Li J, Zhang X, Zimmer MA, Iliopoulos O, Zukerberg LR, Kohgo Y, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:992–997. doi: 10.1038/nm1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carmeliet P. Nat Med. 2002;8:14–16. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynolds LE, Wyder L, Lively JC, Taverna D, Robinson SD, Huang X, Sheppard D, Hynes RO, Hodivala-Dilke KM. Nat Med. 2002;8:27–34. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain RK, Duda DG, Clark JW, Loeffler JS. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:24–40. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdollahi A, Griggs DW, Zieher H, Roth A, Lipson KE, Saffrich R, Grone HJ, Hallahan DE, Reisfeld RA, Debus J, et al. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6270–6279. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hahnfeldt P, Panigrahy D, Folkman J, Hlatky L. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4770–4775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahnfeldt P, Folkman J, Hlatky L. J Theor Biol. 2003;220:545–554. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2003.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdollahi A, Lipson KE, Han X, Krempien R, Trinh T, Weber KJ, Hahnfeldt P, Hlatky L, Debus J, Howlett AR, et al. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3755–3763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huber PE, Bischof M, Jenne J, Heiland S, Peschke P, Saffrich R, Grone HJ, Debus J, Lipson KE, Abdollahi A. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3643–3655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdollahi A, Lipson KE, Sckell A, Zieher H, Klenke F, Poerschke D, Roth A, Han X, Krix M, Bischof M, et al. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8890–8898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turzanski J, Grundy M, Shang S, Russell N, Pallis M. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Sano F, Fazi B, Citro G, Lovat PE, Cesareni G, Piacentini M. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3860–3865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim Y, Suh N, Sporn M, Reed JC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22320–22329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Longley DB, Wilson TR, McEwan M, Allen WL, McDermott U, Galligan L, Johnston PG. Oncogene. 2006;25:838–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abedini MR, Qiu Q, Yan X, Tsang BK. Oncogene. 2004;23:6997–7004. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friess H, Ding J, Kleeff J, Liao Q, Berberat PO, Hammer J, Buchler MW. Ann Surg. 2001;234:769–778. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martignoni ME, Kunze P, Hildebrandt W, Kunzli B, Berberat P, Giese T, Kloters O, Hammer J, Buchler MW, Giese NA, et al. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:5802–5808. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tureci O, Ding J, Hilton H, Bian H, Ohkawa H, Braxenthaler M, Seitz G, Raddrizzani L, Friess H, Buchler M, et al. FASEB J. 2003;17:376–385. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0478com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Friess H, Ding J, Kleeff J, Liao Q, Berberat PO, Hammer J, Buchler MW. Ann Surg. 2001;234:769–778. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdollahi A, Li M, Ping G, Plathow C, Domhan S, Kiessling F, Lee LB, McMahon G, Grone HJ, Lipson KE, et al. J Exp Med. 2005;201:925–935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.