Abstract

Context

There is growing recognition that bipolar disorder (BPD) has a spectrum of expression substantially more common than the 1% BP-I prevalence traditionally found in population surveys.

Objective

To estimate the prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the US population.

Design

Interviews with a nationally representative sample of English-speaking adult (ages 18+) household residents in the continental US

Participants

9,282 respondents.

Main Outcome Measures

Version 3.0 of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview, a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview, was used to assess DSM-IV lifetime and 12 month Axis I disorders. Sub-threshold BPD was defined as recurrent hypomania without a major depressive episode or with fewer symptoms than required for threshold hypomania. Severity was assessed with the Young Mania Rating Scale for mania/hypomania and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms Self-Report for depression. Role impairment among 12-month cases was assessed with the Sheehan Disability Scales.

Results

Lifetime (and 12-month) prevalence estimates are 1.0% (0.6%) for BP-I, 1.1% (0.8%) for B P-II, and 2.4% (1.4%) for sub-threshold BPD. Comorbidity with other lifetime Axis I disorders is the norm both for threshold and sub-threshold cases. While the vast majority of people with BPD receive lifetime professional treatment for emotional problems, use of antimanic medication is much less common than use of inappropriate medications, especially in general medical settings. Clinical severity and role impairment are greater for mania than hypomania, but higher for BP-II than BP-I episodes of MDE. Although clinical severity and role impairment are greater for threshold than sub-threshold BPD, sub-threshold cases consistently have moderate-to-severe clinical severity and role impairment.

Conclusions

Inappropriate treatment of BPD is a serious problem in the U.S. population. Sub-threshold BPD is commonly occurring, clinically significant, and under-detected in treatment settings. Explicit criteria are needed to define sub-threshold BPD for future clinical and research purposes.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder, Bipolar Spectrum, Mania, Hypomania, National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), Comorbidity, Treatment

The estimated lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder (BPD) in population surveys using structured diagnostic interviews and standardized criteria averages approximately 0.8% for BP-I and 1.1% for BP-II.1-8 Despite this comparatively low prevalence, BPD is a leading cause of premature mortality due to suicide and associated medical conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.9, 10 BPD also causes widespread role impairment.11, 12 The recurrent nature of manic and depressive episodes often leads to high direct as well as high indirect health care costs.13, 14

BPD might be even more burdensome from a societal perspective due to the fact that sub-threshold bipolar spectrum disorder has seldom been taken into consideration in examining the epidemiology of BPD. Bipolar spectrum disorder includes hypomania without major depression and hypomania of lesser severity or briefer duration than specified in the DSM and ICD criteria. Although the precise definitions are as yet unclear, recent studies suggest that bipolar spectrum disorder might affect as many as 6% of the general population.15, 16 However, bipolar spectrum disorder has not been studied previously in a nationally representative survey of the US. The purpose of the current report is to present the results of such a study based on analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).17 We estimate prevalence and clinical features of sub-threshold BPD in comparison to BP-I and BP-II.

METHODS

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative survey of mental disorders among English-speaking household residents ages 18 and older in the continental US. Interviews were carried out with 9282 respondents between February 2001 and April 2003. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Consent was verbal rather than written to maintain consistency with the baseline NCS. The response rate was 70.9%. Respondents were given a $50 incentive for participation. A probability sub-sample of hard-to-recruit pre-designated respondents was administered a brief telephone non-respondent survey and results were used to weight the main sample for non-response bias. Non-respondent survey participants were given a $100 incentive. The Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan both approved these recruitment and consent procedures. The NCS-R interview was administered in two parts. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment of all respondents (n = 9282). Part II included questions about correlates and additional disorders administered to all Part I respondents who met lifetime criteria for any core disorder plus a roughly one-in-three probability sub-sample of other respondents (n = 5692). A more detailed discussion of NCS-R sampling and weighting is presented elsewhere.18

Bipolar disorder

NCS-R diagnoses are based on Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),19 a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview. DSM-IV criteria were used to define mania (duration of at least one week), hypomania (duration of at least four days), and major depressive episode (MDE). The requirement that symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode (Criterion C for mania/hypomania and Criterion B for MDE) was not operationalized in making these diagnoses. Respondents were classified as having lifetime BP-I if they ever had a manic episode and as having lifetime BP-II if they ever had a hypomanic but not manic episode and ever had an episode of MDE. Mixed episodes and rapid cycling subtypes of bipolar disorder were not assessed, leading to a likely over-estimation of number of lifetime episodes of mania/hypomania and MDE due to double-counting

Respondents were classified as having sub-threshold BPD in any of three situations: (i) if they had a history of recurrent sub-threshold hypomania (at least two Criterion B symptoms along with all other criteria for hypomania) in the presence of intercurrent MDE; (ii) if they had a history of recurrent (two or more episodes) hypomania in the absence of recurrent MDE with or without sub-threshold MDE; or (iii) if they had a history of recurrent sub-threshold hypomania in the absence of intercurrent MDE with or without sub-threshold MDE. The reduction in number of required symptoms for a determination of sub-threshold hypomania was confined to two Criterion B symptoms (from the DSM-IV requirement of three or four if the mood is only irritable) in order to retain the core features of hypomania in the sub-threshold definition. Recurrent hypomania or sub-threshold hypomania in the absence of intercurrent MDE was included in the definition because it is part of the DSM-IV definition of BPD NOS. For purposes of this paper, we define the bipolar spectrum as a lifetime history of BP-I, BP-II or sub-threshold BPD as defined above. All diagnoses excluded cases with plausible organic causes.

Age-of-onset of manic/hypomanic episodes and of MDE was assessed with retrospective self-reports at the syndrome level. Respondents classified as having lifetime BPD were defined as 12-month cases if they had an episode of MDE, mania, hypomania, or sub-threshold hypomania at any time in the 12 months before interview. Persistence was assessed by asking respondents to estimate the number of years in their life when they had a manic or hypomanic episode and, separately, the number of years when they had a major depressive episode. Clinical reappraisal interviews for BPD using the lifetime non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)20 were administered to a probability sub-sample of 50 NCS-R respondents. It should be noted that this was a special clinical reappraisal sample that focused exclusively on BPD and was distinct from the larger clinical reappraisal sample used to assess the validity of more common DSM-IV disorders.21

CIDI cases were over-sampled in the BPD clinical reappraisal sample and the data weighted for this over-sampling. As described in more detail elsewhere,22 CIDI-SCID concordance was excellent for any BPD (i.e., BP-I, BP-II, or sub-threshold BPD), with κ of .94, positive predictive value (PPV; percent of CIDI cases that are confirmed by the SCID) .88, negative predictive value (NPV; percent of CIDI non-cases confirmed as not being cases by the SCID) 1.0, and an insignificant McNemar test (χ21 = 0.6, p = .45). The McNemar test evaluates whether the CIDI prevalence estimate differs significantly from the SCID prevalence estimate. Concordance (κ) for individual diagnoses was lower, but still acceptable: .88 for BP-I, .50 for BP-II, and .51 for sub-threshold BPD, while PPV was .79, .41, and .58, respectively. NPV was consistently greater than .99 and the McNemar test was consistently insignificant (χ21 = 0.1-0.3, p = .56-.75).

Clinical severity was assessed among 12-month cases using a fully structured self-report version of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)23 for mania/hypomania and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms Self-Report (Q-IDS-SR)24 for MDE. The structured YMRS was based on a fully structured respondent report version developed for parent reports.25 Standard YMRS and QIDS cut-points were used to define episodes as severe (including original YMRS and QIDS ratings of very severe, with ratings in the range 25+ on the YMRS and 16+ on the QIDS), moderate (15-24 on the YMRS; 11-15 on the QIDS), mild (9-14 on the YMRS; 6-10 on the QIDS), or not clinically significant (0-8 on the YMRS; 0-5 on the QIDS). Severity was assessed for the most severe month in the past year. No data were collected on the accuracy of these retrospective reports.

Role impairment among 12-month cases was assessed with the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS).26 As with the YMRS and QIDS, the SDS scales asked respondents to focus on the one month in the past year when their mania/hypomania or MDE symptoms were most severe. The SDS questions asked respondents to rate separately how much the condition interfered during that month with their home management, work, social life, and personal relationships using a 0-10 visual analogue scale of none (0), mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), severe (7-9), and very severe (10).

Other disorders

Other core DSM-IV disorders assessed with the CIDI included other anxiety disorders,mood disorders, impulse-control disorders, and substance use disorders. Organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making all diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere,21, 27 blinded clinical re-interviews using the non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)20 with a probability sub-sample of NCS-R respondents found generally good concordance between CIDI/DSM-IV diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance disorders and independent clinical assessments. Impulse-control disorder diagnoses were not validated, as the SCID clinical reappraisal interviews did not include an assessment of these disorders.

Other measures

Questions were asked about lifetime and 12-month treatment that distinguished treatment by a psychiatrist, other mental health professional, general medical provider, human services professional, and complementary-alternative treatment provider. Questions about 12-month treatment also assessed medication. Mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics were classified as appropriate medications for BPD. Antidepressants and other psychotropic medications in the absence of antimanic agents were classified inappropriate. Twelve-month treatment was assessed separately among respondents with 12-month BPD and lifetime but not 12-month BPD (i.e., maintenance treatment). Appropriateness of medication was examined separately for those in treatment with a psychiatrist and general medical provider.

All analyses included controls for sex, age (18-29, 30-44, 45-59, 60+), race-ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), education (less than high school, completed high school, some college, completed college), and occupation (professional, technical, service-clerical, laborer), as well as for average expected hours of work per week (20-34, 35-44, 45+).

Analysis methods

Sub-group comparisons were used to study lifetime prevalence and persistence of BP-I, BP-I, and sub-threshold BPD. Age-of-onset distributions were estimated using the two-part actuarial method implemented in SAS 8.2.28 The actuarial method differs from the more familiar Kaplan-Meier29 method in using a more accurate way of estimating the timing of onsets within a given year.30 The method, like the Kaplan-Meier method, assumes constant conditional risk of onset at a given year of life across cohorts. Persistence was examined by calculating means and inter-quartile rates of reported years in episode, number of lifetime episodes, and the proportion of lifetime episodes that were manic/hypomanic versus MDE. Comorbidity was assessed by calculating odds-ratios (ORs) between BPD and other CIDI/DSM-IV disorders. Clinical severity, severity of role impairment, and treatment were examined by calculating distributions within the BPD subgroups. Because the NCS-R sample design used weighting and clustering, all statistical analyses were carried out using the Taylor series linearization method,31 a design-based method implemented in the SUDAAN software system.32 Significance tests of set of coefficients were made using Wald χ2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided design-based .05 level tests.

RESULTS

Prevalence, age-of-onset, and persistence

Lifetime prevalence estimates are 1.0% for BP-I, 1.1% for BP-II, and 2.4% for sub-threshold BPD (4.4% overall). (Table 1) Gender-specific (male and female) prevalence estimates are: 0.8% and 1.1% BP-I, 0.9% and 1.3% BP-II, 2.6% and 2.1% sub-threshold BPD. Approximately one-third (36.7%) of sub-threshold cases have a history of recurrent sub-threshold hypomania in the presence of MDE, while 41.9% have a history of recurrent hypomania in the absence of recurrent MDE. The remaining 21.4% have a history of recurrent sub-threshold hypomania in the absence of MDE. Twelve-month prevalence estimates are 0.6% BP-I, 0.8% BP-II, and 1.4% sub-threshold BPD.

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset of DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD) in the total sample (n = 9282)

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Sub-threshold BPD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| Prevalence | ||||||||

| Lifetime | 4.4 | (0.2) | 1.0 | (0.1) | 1.1 | (0.1) | 2.4 | (0.2) |

| 12-month | 2.8 | (0.2) | 0.6 | (0.1) | 0.8 | (0.1) | 1.4 | (0.2) |

| Age-of-onset1 | ||||||||

| Mean (se) | 20.8 | (0.6) | 18.2 | (1.2) | 20.3 | (0.9) | 22.2 | (0.9) |

| IQR2 | 12.6-24.9 | 12.3-21.2 | 12.1-24.0 | 13.0-28.3 | ||||

Retrospectively reported age-of-onset of first manic/hypomanic or depressive episode. The means differ significantly across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level using a two-sided test (χ22 = 7.8, p = .020).

Inter-quartile range (IQR) is the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles on the age-of-onset distribution.

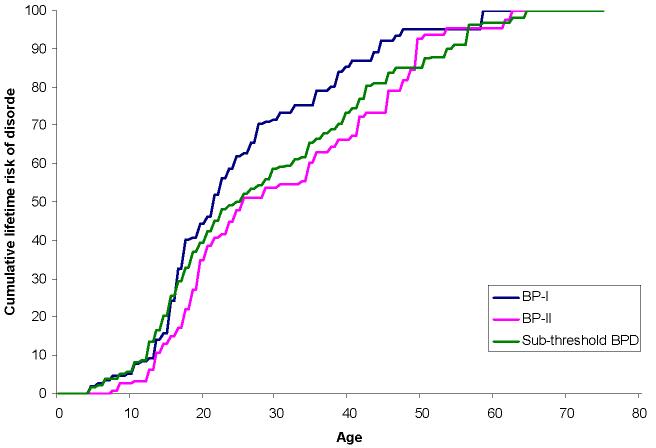

Mean retrospectively reported age-of -onset of first manic/hypomanic or depressive episode is somewhat earlier for BP-I (18.2) and BP-II (20.3) than sub-threshold BPD (22.2). The inter-quartile range (IQR; 25th-75th percentiles of the cumulative age-of-onset distribution) is between the late teens and the early 40s for all three disorders, with the increase in cumulative lifetime prevalence fairly linear in that age range. (Figure 1) Persistence, indirectly indicated by the ratio of 12-month prevalence to lifetime prevalence, is higher for BP-I (63.3%) and BP-II (73.2%) than sub-threshold BPD (59.5%). (Results available on request.) The same pattern is found for retrospectively reported number of years in episode (means of 10.3 BP-I, 11.6 BP-II, 6.8 sub-threshold BPD) and number of lifetime episodes (77.6 BP-I, 63.6 BP-II, 31.8 sub-threshold BPD). More detailed analysis (results available on request) showed that low persistence of sub-threshold BPD is limited to cases without a history of MDE. The ratio of lifetime manic/hypomanic episodes to total episodes is in the range .5-.6 for respondents with lifetime BP-I or BP-II and considerably higher (.8) for sub-threshold BPD due to the inclusion of hypomania in the absence of MDE. Twelve-month ratios are very similar to lifetime ratios.

Figure 1.

Cumulative age of onset distributions of DSM-IV/CIDI BP-I, BP-II, and sub-threshold BPD among respondents projected to develop these disorders in their lifetime1

Socio-demographic correlates

The socio-demographic correlates of BPD in the NCS-R are modest in magnitude but fairly consistent across the BPD spectrum. BPD is inversely related to age and education, elevated among the previously married compared to the currently married (only for sub-threshold BPD) and the unemployed-disabled compared to the employed. BPD is unrelated to gender, race-ethnicity, and family income. (Results not presented, but available on request.)

Comorbidity with other DSM-IV disorders

Lifetime comorbidity with other DSM-IV/CIDI disorders was reported by the vast majority of respondents with a history of threshold (97.7-95.8%) and sub-threshold (88.4%) BPD. (Table 2) Odds-ratios (OR’s) of BPD with individual disorders are uniformly significant and generally higher for BP-I (5.2-13.7) and BP-II (2.6-16.7) than sub-threshold BPD (2.2-5.0). An exception is OR’s with some impulse-control disorders and substance disorders being much higher for BP-I than either BP-I or sub-threshold BPD. The OR’s of BPD with presence of three or more other disorders are dramatically higher than with individual disorder across the BPD spectrum (112.3 BP-I, 58.3 BP-II, 14.3 sub-threshold BPD).

Table 2.

Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD) with other DSM-IV/CIDI disorders in the total sample (n = 9282)

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Sub-threshold BPD | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %1 | (se) | OR2 | (95% CI) | %1 | (se) | OR2 | (95% CI) | %1 | (se) | OR2 | (95% CI) | %1 | (se) | OR2 | (95% CI) | χ224 | |

| I. Anxiety disorders | |||||||||||||||||

| Agoraphobia without panic | 5.7 | (1.3) | 5.3* | (3.0-9.3) | 5.6 | (2.3) | 5.2* | (2.1-13.0) | 8.1 | (2.8) | 7.2* | (3.3-15.8) | 4.6 | (1.8) | 4.3* | (1.7-10.8) | 1.1 |

| Panic disorder | 20.1 | (2.0) | 5.8* | (4.4-7.7) | 29.1 | (4.4) | 9.4* | (5.9-15.1) | 27.2 | (5.3) | 8.1* | (4.7-14.1) | 13.1 | (2.5) | 3.6* | (2.3-5.6) | 13.5** |

| Panic attacks | 61.9 | (2.0) | 4.3* | (3.5-5.2) | 63.9 | (4.5) | 4.6* | (3.0-6.9) | 72.9 | (4.8) | 7.1* | (4.3-11.5) | 56.0 | (3.1) | 3.4* | (2.6-4.4) | 6.7** |

| PTSD | 24.2 | (2.6) | 4.7* | (3.3-6.8) | 30.9 | (4.4) | 6.6* | (4.2-10.4) | 34.3 | (4.1) | 7.3* | (4.9-10.8) | 16.5 | (3.4) | 3.0* | (1.7-5.3) | 9.1** |

| GAD | 29.6 | (2.5) | 6.1* | (4.6-8.1) | 38.7 | (4.7) | 9.4* | (6.2-14.2) | 37.0 | (4.8) | 7.7* | (5.1-11.7) | 22.3 | (3.4) | 4.3* | (2.8-6.7) | 6.4** |

| Specific phobia | 35.5 | (2.8) | 4.0* | (3.1-5.2) | 47.1 | (4.3) | 6.5* | (4.5-9.4) | 51.1 | (5.0) | 7.5* | (5.1-11.0) | 23.3 | (3.5) | 2.2* | (1.5-3.4) | 25.7** |

| Social phobia | 37.8 | (3.1) | 4.6* | (3.5-5.9) | 51.6 | (5.9) | 7.9* | (4.9-12.8) | 54.6 | (5.4) | 9.0* | (6.0-13.7) | 24.1 | (3.7) | 2.4* | (1.6-3.6) | 27.8** |

| OCD | 13.6 | (3.1) | 10.2* | (4.6-22.9) | 25.2 | (7.3) | 21.4* | (7.6-60.1) | 20.8 | (9.1) | 16.7* | (4.7-59.7) | 4.3 | (2.5) | 3.0 | (0.9-10.6) | 6.6** |

| SAD | 35.4 | (2.0) | 5.4* | (4.6-6.5) | 41.2 | (6.0) | 6.8* | (4.1-11.3) | 42.8 | (5.5) | 7.7* | (4.9-12.2) | 29.4 | (3.4) | 4.1* | (2.9-5.7) | 4.9** |

| Any anxiety disorder | 74.9 | (2.8) | 6.5* | (4.7-9.0) | 86.7 | (3.9) | 14.1* | (6.9-28.8) | 89.2 | (3.3) | 17.6* | (9.0-34.7) | 63.1 | (3.8) | 3.8* | (2.6-5.4) | 29.9** |

| II. Impulse-control disorders3 | |||||||||||||||||

| IED | 28.9 | (2.5) | 4.5* | (3.6-5.8) | 38.1 | (4.6) | 6.7* | (4.4-10.1) | 22.9 | (4.9) | 3.6* | (2.1-6.3) | 27.9 | (3.5) | 4.2* | (2.9-6.0) | 4.1 |

| ADHD | 31.4 | (3.2) | 6.7* | (4.8-9.3) | 40.6 | (5.9) | 10.0* | (6.1-16.1) | 42.3 | (7.5) | 10.4* | (5.7-18.8) | 23.0 | (3.9) | 4.4* | (2.6-7.4) | 7.4** |

| ODD | 36.8 | (3.1) | 6.1* | (4.5-8.4) | 44.4 | (6.4) | 8.5* | (5.1-14.1) | 38.2 | (7.2) | 7.0* | (3.5-14.3) | 32.8 | (4.1) | 5.0* | (3.5-7.1) | 3.3 |

| CD | 30.3 | (3.1) | 4.9* | (3.6-6.7) | 43.8 | (5.9) | 8.9* | (5.6-14.2) | 18.6 | (5.1) | 2.6* | (1.3-5.1) | 28.9 | (3.8) | 4.5* | (3.0-6.8) | 10.6** |

| Any impulse-control disorder | 62.8 | (2.9) | 5.6* | (4.3-7.3) | 71.2 | (5.1) | 8.3* | (5.2-13.2) | 70.4 | (6.7) | 8.1* | (4.3-15.4) | 56.1 | (3.8) | 4.2* | (3.0-6.0) | 7.5** |

| III. Substance use disorders | |||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 39.1 | (2.6) | 4.3* | (3.3-5.5) | 56.3 | (3.6) | 8.6* | (5.9-12.4) | 36.0 | (4.4) | 3.7* | (2.4-5.7) | 33.2 | (4.3) | 3.3* | (2.3-4.8) | 17.2** |

| Alcohol dependence | 23.2 | (1.9) | 5.7* | (4.3-7.6) | 38.0 | (5.0) | 11.6* | (6.8-19.7) | 19.0 | (3.8) | 4.4* | (2.4-7.8) | 18.9 | (3.5) | 4.5* | (3.0-6.8) | 10.2** |

| Drug abuse | 28.8 | (2.7) | 4.5* | (3.3-5.9) | 48.3 | (3.8) | 10.1* | (7.0-14.4) | 23.7 | (3.4) | 3.5* | (2.4-5.3) | 22.9 | (3.9) | 3.2* | (2.1-5.1) | 15.4** |

| Drug dependence | 14.0 | (1.8) | 5.2* | (3.7-7.2) | 30.4 | (4.1) | 13.7* | (8.9-21.1) | 8.7 | (3.1) | 3.1* | (1.4-6.8) | 9.5 | (2.3) | 3.4* | (2.0-5.7) | 18.3** |

| Any substance | 42.3 | (2.7) | 4.2* | (3.3-5.5) | 60.3 | (4.2) | 8.8* | (5.9-13.1) | 40.4 | (3.7) | 3.9* | (2.7-5.7) | 35.5 | (4.3) | 3.2* | (2.2-4.6) | 18.8** |

| IV. Any disorder | |||||||||||||||||

| Any disorder4 | 92.3 | (2.2) | 13.1* | (6.7-25.5) | 97.7 | (1.6) | 47.7* | (11.3-201.3) | 95.8 | (2.5) | 24.5* | (7.1-85.1) | 88.4 | (3.7) | 8.5* | (3.9-18.2) | 10.7** |

| Exactly 1 disorder | 12.7 | (2.0) | 4.8* | (2.2-10.4) | 8.1 | (3.1) | 10.2* | (1.9-54.3) | 7.0 | (2.3) | 4.8* | (1.2-19.0) | 17.1 | (3.7) | 4.3* | (1.7-10.9) | 0.8 |

| Exactly 2 disorders | 9.4 | (1.7) | 5.6* | (2.5-12.5) | 3.4 | (2.1) | 6.9* | (1.0-48.5) | 2.9 | (2.2) | 3.3 | (0.5-22.8) | 14.7 | (2.7) | 5.8* | (2.3-14.7) | 0.3 |

| 3 or more disorders | 70.1 | (2.5) | 26.4* | (13.7-50.8) | 86.2 | (3.7) | 112.3* | (27.2-464.6) | 85.8 | (4.2) | 58.3* | (16.3-208.4) | 56.7 | (3.8) | 14.3* | (6.9-29.5) | 18.1** |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Significant difference across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level, two-sided test

The prevalence of the comorbid disorder among respondents with BPD

Based on logistic regression models with one DSM-IV/CIDI disorder at a time as a predictor of LT BPD, controlling for age at interview (5-year intervals) sex, and race-ethnicity. The last model had predictors “exactly one,” “exactly two” and “exactly three” disorders in one model.

Sample included Part II respondents whose age at interview was less than or equal to 44 (n = 3197)

Test of the significance of difference in ORs across the three BPD subgroups

Severity of 12-month cases

YMRS 12-month episode severity was rated severe in a higher proportion of BP-I (70.2%) than BP-II (55.4%) or sub-threshold BPD (31.5%). (Table 3) The vast majority of manic/hypomanic episodes were classified either severe or moderate across the BPD spectrum 87.3-94.6%). QIDS-SR 12-month severity was rated more severe for BP-II (84.0%) than BP-I (70.5%) or BPD (46.4%). As with mania/hypomania, the vast majority of MDE episodes were classified either severe or moderate across the spectrum (92.3-100.0%).

Table 3.

Clinical severity among respondents with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD)

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Sub-threshold BPD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ221 | |

| I. Manic/hypomanic episode2 | |||||||||

| Severe | 45.6 | (3.5) | 70.2 | (8.7) | 55.4 | (7.0) | 31.5 | (4.7) | 17.6* |

| Moderate | 44.4 | (4.3) | 24.4 | (8.1) | 31.9 | (7.0) | 58.1 | (5.3) | 1.1 |

| Mild | 8.0 | (2.3) | 5.4 | (3.9) | 9.2 | (4.1) | 8.3 | (3.6) | 311.3* |

| None | 2.1 | (1.1) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 3.5 | (3.3) | 2.1 | (1.3) | - |

| (n)3 | (219) | (52) | (60) | (107) | |||||

| II. Major depressive episode4 | |||||||||

| Severe | 69.5 | (5.5) | 70.5 | (8.1) | 84.0 | (5.9) | 46.4 | (9.9) | 13.4* |

| Moderate | 27.7 | (5.3) | 21.8 | (7.9) | 14.8 | (5.6) | 53.6 | (9.9) | 209.3* |

| Mild | 2.8 | (1.4) | 7.6 | (4.2) | 1.2 | (1.2) | 0.0 | (0.0) | -6 |

| None | 0.0 | (0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0) | - |

| (n)3 | (152) | (43) | (60) | (49) | |||||

| III. Combined2,5 | |||||||||

| Severe | 58.4 | (3.5) | 70.3 | (7.7) | 79.2 | (5.7) | 40.3 | (4.7) | 19.1* |

| Moderate | 37.1 | (4.1) | 21.4 | (7.4) | 18.0 | (5.1) | 55.9 | (5.2) | 1.8 |

| Mild | 4.2 | (1.6) | 8.2 | (4.8) | 2.9 | (1.6) | 3.2 | (2.2) | 295.9* |

| None | 0.3 | (0.3) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 0.6 | (0.6) | - |

| (n)3 | (262) | (65) | (74) | (123) | |||||

Significant difference across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level, two-sided test

Significance tests were carried out for cumulative categories. In the case of moderate severity, the BPD subgroups were compared for prevalence of severe or moderate. In the case of mild severity, the BPD subgroups were compared for prevalence of any severity (i.e., severe, moderate or mild) versus none. No significance tests are presented for the final category (None) because of this cumulative coding.

Based on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)22

Number of 12-month cases of mania/hypomania (I), major depressive episode among people with 12-month BPD (II), and any 12-month BPD (III) in the sample

Based on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms Self-Report version (QIDS-SR)23

Respondents who reported both manic/hypomanic and depressive episodes in the past year were assigned the more severe of their two severity scores.

No respondents were classified mild.

Severe role impairment due to 12-month mania/hypomania was reported by 73.1% of those with 12-month BP-I, 64.6% BP-II, and 45.9% sub-threshold BPD. (Table 4) Severe role impairment due to 12-month MDE among people with BPD was reported by even higher proportions of 12-month cases. As with clinical severity, severe role impairment due to MDE was more common among cases with BP-II (91.4%) than BP-I (89.3%) or sub-threshold BPD (78.8%). Reports of moderate or severe impairment were also more common for MDE (98.6-100.0%) than mania/hypomania (87.3-100%). Impairment was common in all the domains assessed by the Sheehan scales.

Table 4.

Severity of role impairment across role domains among respondents with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD)1

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Subthreshold BPD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ222 | |

| I. Severity of role impairment associated with 12-month mania/hypomania | |||||||||

| Severe | 56.6 | 3.4 | 73.1 | 7.8 | 64.6 | 5.7 | 45.9 | 5.8 | 9.0 |

| Moderate | 33.6 | 3.1 | 26.9 | 7.8 | 22.7 | 5.5 | 41.9 | 4.7 | 2365.4 |

| Mild | 6.1 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 9.3 | 3.2 | 881.7 |

| None | 3.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 1.7 | -- |

| (n) | (219) | (52) | (60) | (107) | |||||

| II. Severity of role impairment associated with 12-month MDE | |||||||||

| Severe | 87.4 | 4.0 | 89.3 | 4.9 | 91.4 | 4.1 | 78.8 | 9.0 | 2.3 |

| Moderate | 12.0 | 3.9 | 10.7 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 3.8 | 21.2 | 9.0 | 165.0 |

| Mild | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

| None | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

| (n) | (152) | (43) | (60) | (49) | |||||

*Significant difference across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level, two-sided test

Based on the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS)24. Respondents were assigned their highest rating of impairment across the four SDS domains

Significance of differences across three BPD subgroups in Part II was evaluated for cumulative categories. In the case of moderate severity, the BPD subgroups were compared for prevalence of severe or moderate. In the case of mild severity, the subgroups were compared for prevalence of any severity (i.e., severe, moderate or mild) versus none.

Treatment

Lifetime treatment of emotional problems was reported by 80.1% of respondents with lifetime BPD. (Table 5) This reflects treatment to date. Others might receive treatment in the future. Treatment to date is more common for BP-I and BP-II (89.2-95.0%) than sub-threshold BPD (69.3%), although even the latter is high in comparison to other DSM-IV/CIDI disorders.33 Psychiatrists were the most common providers for BP-I (64.9%) and BP-II (62.2%) and general medical professionals for sub-threshold BPD (37.5%).

Table 5.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment of DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD)

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Sub-threshold BPD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ2 | |

| I. Lifetime Treatment | |||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 44.8 | (2.7) | 64.9 | (5.0) | 62.2 | (5.5) | 28.2 | (3.2) | 30.1* |

| Other mental health | 42.3 | (2.8) | 57.2 | (6.0) | 52.0 | (4.8) | 31.5 | (4.0) | 13.3* |

| Any mental health | 59.3 | (2.8) | 72.3 | (4.6) | 78.8 | (5.2) | 44.8 | (4.3) | 17.9* |

| General medical | 44.8 | (2.7) | 53.3 | (5.4) | 52.7 | (5.1) | 37.5 | (3.2) | 10.5* |

| Human services | 23.0 | (2.1) | 28.4 | (4.4) | 27.5 | (4.5) | 18.6 | (2.7) | 7.4* |

| CAM | 26.0 | (2.8) | 37.0 | (5.1) | 31.8 | (5.5) | 18.7 | (2.8) | 17.4* |

| Any | 80.1 | (1.8) | 89.2 | (3.4) | 95.0 | (2.3) | 69.3 | (3.1) | 30.8* |

| (n) | (416) | (101) | (105) | (210) | |||||

| II. Twelve-month Treatment | |||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 18.3 | (1.8) | 35.2 | (4.9) | 26.2 | (3.9) | 7.6 | (2.0) | 26.0* |

| Other mental health | 22.2 | (1.7) | 35.4 | (4.7) | 26.7 | (3.9) | 14.6 | (2.2) | 17.8* |

| Any mental health | 29.2 | (1.9) | 46.1 | (4.6) | 39.0 | (4.6) | 17.5 | (2.6) | 30.0* |

| General medical | 25.4 | (2.3) | 27.6 | (4.8) | 33.8 | (6.0) | 20.6 | (3.1) | 4.4 |

| Human services | 10.9 | (1.7) | 15.9 | (3.0) | 10.9 | (4.1) | 8.9 | (2.1) | 3.6 |

| CAM | 10.6 | (1.8) | 17.3 | (4.1) | 15.6 | (3.9) | 5.5 | (1.7) | 14.0* |

| Any | 50.7 | (2.6) | 67.3 | (3.8) | 65.8 | (5.8) | 36.7 | (3.4) | 42.0* |

| (n) | (262) | (65) | (74) | (123) | |||||

Significant difference across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level, two-sided test

1Treatment either for mania/hypomania or for MDE

Summing treatment proportions across sectors shows multiple-sector to be the norm, with a 2.2-sector average among patients (2.7 BP-I, 2.4 BP-II, 1.9 sub-threshold BPD) Treatment of 12-month BPD was quite high in relation to other DSM-IV/CIDI disorders:34 67.3% BP-I, 65.8% BP-II, 36.7% sub-threshold BPD. Unlike lifetime treatment, though, non-psychiatrist mental health professionals were the most common providers (35.4% BP-I, 33.8% BP-II, 20.6% sub-threshold BPD). Multi-sector treatment was the norm, with a 1.7-sector mean.

Appropriate medication use could be analyzed only for 12-month treatment. (Table 6) A significantly higher proportion of cases in psychiatric (45.0%) than general medical (9.0%) treatment received appropriate medication. A significantly higher proportion of cases in general medical (73.1%) than psychiatric (43.4%) treatment received inappropriate medication. A significant gradient was found in the proportion of all 12-month cases (ignoring whether they received treatment) that received appropriate medication: 25.0% BP-I, 15.4% BP-II, 8.1% sub-threshold BPD. The proportion receiving inappropriate medication was also higher for BP-I (38.7%) and BP-II (38.9%) than sub-threshold BPD (23.8%). The opposite pattern was found for the proportion receiving no medication (36.3% BP-I, 45.7% BP-II, 68.1% sub-threshold BPD). The numbers were two small to distinguish 12-month cases with mania/hypomania-only, MDE-only, and both with adequate statistical power. A significant gradient also was found in the proportion of lifetime cases without a 12-month episode (ignoring whether they received 12-month treatment) that received appropriate maintenance medication: 17.9% BP-I, 15.6% BP-II, 3.2% sub-threshold BPD. The proportion of all lifetime cases that received inappropriate medication was also higher for BP-I (35.3%) than BP-II (24.5%) or sub-threshold BPD (21.5%). The opposite pattern was found for the proportion receiving no medication (46.8% BP-I, 59.9% BP-II, 75.3% sub-threshold BPD).

Table 6.

Twelve-month use of appropriate medication among respondents with DSM-IV/CIDI bipolar disorder (BPD)1

| Any BPD | BP-I | BP-II | Sub-threshold BPD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ2 | |

| I. Twelve-month cases | |||||||||

| A. Psychiatrist | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 45.0 | (6.4) | 41.6 | (10.1) | 45.1 | (11.1) | 51.5 | (14.5) | 1.0 |

| Other medication | 43.4 | (6.9) | 51.7 | (10.9) | 39.9 | (11.2) | 32.7 | (14.2) | 8.0* |

| No medication | 11.6 | (4.8) | 6.7 | (4.9) | 14.9 | (9.5) | 15.8 | (10.2) | 1.7 |

| (n) | (59) | (27) | (20) | (12) | |||||

| B. General medical (not including those treated by a psychiatrist) | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 9.0* | (4.2) | 0.0* | (0.0) | 3.5* | (3.8) | 15.0* | (7.6) | 4.0 |

| Other medication | 73.1* | (6.3) | 70.9 | (17.5) | 89.2 | (7.8) | 62.4 | (9.2) | 7.4* |

| No medication | 17.9 | (4.8) | 29.1 | (17.5) | 7.3 | (6.8) | 22.6 | (7.9) | 0.6 |

| (n) | (52) | (8) | (16) | (28) | |||||

| C. Total1 | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 13.9 | (2.4) | 25.0 | (6.8) | 15.4 | (4.1) | 8.1 | (2.5) | 8.5* |

| Other medication | 31.4 | (2.6) | 38.7 | (6.6) | 38.9 | (5.4) | 23.8 | (3.6) | 5.3 |

| No medication | 54.7 | (3.0) | 36.3 | (6.1) | 45.7 | (4.0) | 68.1 | (4.7) | 14.6* |

| (n) | (262) | (65) | (74) | (123) | |||||

| II. Lifetime cases (excluding 12-month cases)2 | |||||||||

| A. Psychiatrist | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 41.1 | (13.1) | 46.7 | (13.9) | 28.4 | (17.1) | 48.9 | (25.7) | 0.9 |

| Other medication | 43.3 | (12.9) | 32.0 | (13.2) | 52.4 | (18.3) | 51.1 | (25.7) | 2.7 |

| No medication | 15.6 | (7.7) | 21.3 | (14.1) | 19.2 | (12.9) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 3.6 |

| (n) | (23) | (10) | (8) | (5) | |||||

| B. General medical (not including those treated by a psychiatrist) | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 6.9* | (6.7) | 0.0* | (0.0) | 42.7 | (30.9) | 0.0* | (0.0) | 1.2 |

| Other medication | 65.6 | (12.7) | 43.0 | (24.6) | 40.8 | (30.5) | 84.9 | (10.9) | 2.4 |

| No medication | 27.4 | (11.5) | 57.0 | (24.6) | 16.5 | (16.9) | 15.1 | (10.9) | 2.6 |

| (n) | (17) | (6) | (3) | (8) | |||||

| C. Total1 | |||||||||

| Appropriate medication | 8.8 | (2.8) | 17.9 | (5.7) | 15.6 | (8.2) | 3.2 | (1.9) | 9.8* |

| Other medication | 25.1 | (3.8) | 35.3 | (7.8) | 24.5 | (8.8) | 21.5 | (4.8) | 1.9 |

| No medication | 66.1 | (3.6) | 46.8 | (7.1) | 59.9 | (10.0) | 75.3 | (4.9) | 8.5* |

| (n) | (154) | (36) | (31) | (87) | |||||

Significant difference across the three BPD subgroups at the .05 level, two-sided test

The denominator for C in both Part I and Part I includes cases not in treatment. The proportion with appropriate medication in C exceeds the sum of the weighted proportions in A and B due to the fact that some respondents reported use of appropriate medications even though they reported not having seen either a psychiatrist or a general medical professional at any time in the past 12 months.

Part II presents data on 12-month maintenance medication among lifetime cases who reported not having an episode of either mania/hypomania or MDE in the past 12 months.

COMMENT

The results are limited by the use of fully structured lay-administered CIDI interviews rather than clinician-administered interviews, although the clinical reappraisal study found good concordance of CIDI diagnoses with blinded clinical diagnoses based on the SCID, reducing concern about validity. Concordance was quite high for BP-I (κ = .88) and any BPD (κ = .94), but considerably lower, although still acceptable, for BP-II (κ = .50) and sub-threshold BPD (κ = .51), due to the CIDI having difficulty distinguishing between BP-II and sub-threshold BPD.22 A related limitation is absence of information on mixed episodes, rapid cycling or brief episodes that could be assessed in more flexible semi-structured clinical interviews. Our definition of sub-threshold BPD is consequently more restrictive than the definitions proposed by clinical researchers.16, 35-37 The less flexible assessment than clinical interviews also could have led to overestimation of comorbidity and bias in retrospective recall of persistence. No data are available on accuracy of these reports. The less flexible nature of the CIDI than clinical interviews also could have led to over-estimation of comorbidity and bias in estimated clinical severity and persistence. No data were collected on accuracy of these reports.

Within the context of these limitations, the results provide the first nationally representative US general population prevalence estimates of sub-threshold bipolar disorder. BP-I and BP-II prevalence estimates (1.0-1.1%) are consistent with estimates from earlier population-based studies,1, 3-8 with the exception of a much higher lifetime prevalence estimate of BP-I (3.3%) in a very large recent national survey of the US.2 No clinical validation of the latter estimate was reported. It is noteworthy that the NCS-R clinical reappraisal study confirmed the much lower NCS-R BP-I prevalence estimate. Estimated averages of 77.6 lifetime episodes for BP-I and 63.6 for BP-II are somewhat higher than in prospective studies and family studies,38, 39 indicating possible over-estimation due to retrospective recall bias.

For reasons noted above regarding limitations, the NCS-R sub-threshold BPD prevalence estimate is likely to be a lower bound, although it is broadly consistent with two large community epidemiological surveys in Europe.40, 41 The NCS-R results clearly document the clinical significance of sub-threshold BPD, as the vast majority of sub-threshold cases had moderate-severe symptom profiles and role impairment based on standard rating scales. As one might expect, there was lower episode persistence and a lower severe-to-moderate ratio among sub-threshold vs. threshold cases. Consistent with previous research, the proportions of depressive episodes rated severe were higher for BP-II than BP-I and lowest for sub-threshold BPD.15 The more striking results from the perspective of sub-threshold BPD, though, are that the clinical severity, role impairment, and comorbidity of sub-threshold BPD are all quite high and, indeed, comparable to those of non-bipolar major depression reported in previous NCS-R analyses.42 These findings strongly argue for the clinical significance of sub-threshold BPD.

After controlling for time at risk,43 the high comorbidity of threshold BPD is consistent with prior clinical44, 45 and population-based2, 3, 46-48 studies, although comorbidity with substance use disorders was more prominently featured in previous studies. The higher comorbidity found here with anxiety and impulse-control disorders was less consistently studied in previous research.49, 50 Despite the higher disorder-specific comorbidity of threshold than sub-threshold BPD, comorbidity with at least one other disorder was nearly as common in sub-threshold (88.4%) as threshold (95.8-97.7%) cases. This means that the generally lower bivariate comorbidity of sub-threshold than threshold BPD is due to lower multimorbidity51 (i.e., comorbidity with multiple conditions). This pervasive comorbidity across the bipolar spectrum is suggestive of disturbances in multiple regulatory systems and should be a topic for future research.

The vast majority of NCS-R respondents with threshold (87.1-91.5%) or sub-threshold (67.8%) BPD reported lifetime treatment for emotional problems. However, treatment in the year before interview was lower both for threshold (67.3-65.8%) and sub-threshold (36.7%) cases and only a minority received appropriate medication (25.0% BP-I, 15.4% BP-III, 8.1% sub-threshold BPD). Appropriate maintenance medication of asymptomatic lifetime cases was even lower (17.9% BP-I, 15.6% BP-III, 3.2% sub-threshold BPD). The proportions receiving inappropriate medication (primarily antidepressants in the absence of antimania agents) were considerably higher (31.4% 12-month cases, 25.1% asymptomatic lifetime cases), especially among patients in general medical treatment (73.1% 12-month cases, 65.6% asymptomatic lifetime cases). Appropriate medication was much higher and inappropriate medication lower among patients in psychiatric treatment, although fewer than half of psychiatric patients took appropriate medications (45.0% of 12-month cases, 41.1% of asymptomatic lifetime cases). The high use of inappropriate medications is a concern given the dangers associated with use of antidepressants in the absence of mood stabilizers to treat BPD.52 It is noteworthy that the treatment percentages represent patients who took medications. The numbers who were prescribed but did not take medications were not recorded in the survey. It is quite possible that higher proportions were prescribed antimanic agents but did not take them, as subjective distress is greater for depression than mania/hypomania.11

Although providing only a lower bound estimate on prevalence of sub-threshold BPD, our results reinforce the argument of others that clinically significant sub-threshold BPD is at least as common as threshold BPD.16, 35-37 Although most of those with BPD receive treatment due to comorbid disorders, the lack of recognition of their underlying bipolarity leads to only a minority receiving appropriate treatment. Clearly, more comprehensive screening of bipolar symptoms is needed among patients presenting for treatment of other Axis I disorders. The failure to recognize sub-threshold BPD can also reduce the precision of estimates and lead to bias in genetic and other etiologic studies of mood disorders.53-55 Additional research is needed to resolve uncertainty regarding the most appropriate boundary distinctions for BPD. This uncertainty remains a major impediment to advancing our understanding of the bipolar spectrum in the population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant # 044780), and the John W. Alden Trust. Additional support for preparation of this paper was provided by AstraZeneca. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), T Bedirhan Ustun (World Health Organization), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. Send correspondence to NCS@hcp.med.harvard.edu. The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centers for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (1R13MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc. and the Pan American Health Organization. A complete list of WMH publications and instruments can be found at (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the view of the NIMH, NIH, HHS of the United States Government.

Footnotes

Onset is defined as the age of first occurrence of either a manic/hypomanic or major depressive episode.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer M, Pfennig A. Epidemiology of bipolar disorders. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 4):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.463003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1205–1215. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pini S, de Queiroz V, Pagnin D, Pezawas L, Angst J, Cassano GB, Wittchen HU. Prevalence and burden of bipolar disorders in European countries. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM, Hsu L. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:124–138. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angst J. Bipolar disorder--a seriously underestimated health burden. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:59–60. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tohen M, Angst J. Epidemiology of bipolar disorder. In: Tsuang M, Tohen M, editors. Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 427–444. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittchen HU, Mhlig S, Pezawas L. Natural course and burden of bipolar disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:145–154. doi: 10.1017/S146114570300333X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen H, Yeh EK. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kupfer DJ. The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2005;293:2528–2530. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Reed M, Davies MA, Frye MA, Keck PE, Lewis L, McElroy SL, McNulty JP, Wagner KD. Impact of bipolar disorder on a U.S. community sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:425–432. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean BB, Gerner D, Gerner RH. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and healthcare costs and utilization in bipolar disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:139–154. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large U.S. employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:5–14. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinman L, Lowin A, Flood E, Gandhi G, Edgell E, Revicki D. Costs of bipolar disorder. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:601–622. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200321090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell B-E, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Stang PE. Validity of version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) assessment of bipolar spectrum disorder. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res in press.

- 23.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gracious BL, Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Discriminative validity of a parent version of the Young Mania Rating Scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1350–1359. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, Howes MJ, Jin R, Vega WA, Walters EE, Wang P, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute . SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements, Release 8.2. SAS Publishing; Cary, NC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halli SS, Rao KV, Halli SS. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. Plenum; NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolter K. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Research Triangle Institute . SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis. 8.01 ed. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang PS, Lane M, Kessler RC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the U.S.: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiskal HS, Bourgeois ML, Angst J, Post R, Moller H, Hirschfeld R. Re-evaluating the prevalence of and diagnostic composition within the broad clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(Suppl 1):S5–S30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiskal HS, Benazzi F. Optimizing the detection of bipolar II disorder in outpatient private practice: toward a systematization of clinical diagnostic wisdom. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:914–921. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisfalen ME, Schulze TG, DePaulo JR, Jr., DeGroot LJ, Badner JA, McMahon FJ. Familial variation in episode frequency in bipolar affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1266–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Keck PE, Jr., Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Grunze H, Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Walden J, Nolen WA. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder based on prospective mood ratings in 539 outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1273–1280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regeer EJ, ten Have M, Rosso ML, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Vollebergh W, Nolen WA. Prevalence of bipolar disorder in the general population: a reappraisal study of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:374–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szadoczky E, Papp Z, Vitrai J, Rihmer Z, Furedi J. The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary. Results from a national epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer HC, Wilson KA, Hayward C. Lifetime prevalence and pseudocomorbidity in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:604–608. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:191–206. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown ES. Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell PB, Slade T, Andrews G. Twelve-month prevalence and disability of DSM-IV bipolar disorder in an Australian general population survey. Psychol Med. 2004;34:777–785. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller MB. Prevalence and impact of comorbid anxiety and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 1):5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Cooper J, Potash JB, Simpson SG, Gershon E, Nurnberger J, Reich T, DePaulo JR. Comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder in families with a high prevalence of bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:30–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR. Depressive spectrum diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(00)80007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Dial E, Oster EF, Greenberg PE, Mallett DA. Economic consequences of not recognizing bipolar disorder patients: a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1201–1209. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertelsen A, Harvald B, Hauge M. A Danish twin study of manic-depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;130:330–351. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merikangas KR, Risch N. Will the genomics revolution revolutionize psychiatry? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:625–635. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacQueen GM, Hajek T, Alda M. The phenotypes of bipolar disorder: relevance for genetic investigations. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:811–826. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]