Abstract

Loss of synaptic activity or innervation induces sprouting of intact motor nerve terminals that adds or restores nerve-muscle connectivity. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and terminal Schwann cells (tSCs) have been implicated as molecular and cellular mediators of the compensatory process. We wondered if the previously reported lack of terminal sprouting in CNTF null mice was due to abnormal reactivity of tSCs. To this end, we examined nerve terminal and tSC responses in CNTF null mice using experimental systems that elicited extensive sprouting in wildtype mice. Contrary to the previous report, we found that motor nerve terminals in the null mice sprout extensively in response to major sprouting-stimuli such as exogenously applied CNTF per se, botulinum toxin-elicited paralysis, and partial denervation by L4 spinal root transection. In addition, the number, length and growth patterns of terminal sprouts, and the extent of reinnervation by terminal or nodal sprouts, were similar in wildtype and null mice. tSCs in the null mice were also reactive to the sprouting-stimuli, elaborating cellular processes that accompanied terminal sprouts or guided reinnervation of denervated muscle fibers. Lastly, CNTF was absent in quiescent tSCs in intact, wildtype muscles and little if any was detected in reactive tSCs in denervated muscles. Thus, CNTF is not required for induction of nerve terminal sprouting, for reactivation of tSCs, and for compensatory reinnervation after nerve injury. We interpret these results to support the notion that compensatory sprouting in adult muscles is induced primarily by contact-mediated mechanisms, rather than by diffusible factors.

Keywords: endplate, inactivity, neuromuscular junction, nodal sprouting, paralysis, partial denervation, terminal Schwann cell, terminal sprouting, reinnervation

INTRODUCTION

Paralysis or partial denervation elicits reactive sprouting of intact axons and nerve terminals in adult muscles known as nodal and terminal sprouting (Hoffman, 1950, Duchen and Strich, 1968). These sprouts add or restore synaptic contacts on inactive (Snider and Harris, 1979, Angaut-Petit et al., 1990, Meunier et al., 2002) or denervated muscle fibers, which improve the motor deficits associated with peripheral nerve injury (Brown et al., 1981, Wernig and Herrera, 1986, Tam and Gordon, 2003a) or spinal cord injury (Yang et al., 1990, Marino et al., 1994, Thomas et al., 1997). Despite its significance for repair of the adult nervous system, the molecular and cellular events leading to the compensatory process remain elusive.

Several neurotrophic factors, including Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF), elicit terminal sprouting when they are administered exogenously to intact muscles (Caroni and Grandes, 1990, Gurney et al., 1992, Caroni et al., 1994, Kwon and Gurney, 1994, Funakoshi et al., 1995, Tarabal et al., 1996, Trachtenberg and Thompson, 1997, Siegel et al., 2000). Although the physiological roles of most of these diffusible factors remain unclear, an earlier genetic analysis of CNTF null (−/−) mice provided evidence for the particular importance of CNTF as a key mediator of the sprouting responses; Siegel et al. (2000) reported that paralysis, partial denervation, and exogenous CNTF all failed to elicit significant sprouting in the null mice and concluded that CNTF is required for motor nerve sprouting. The same group subsequently proposed that CNTF, released from Schwann cells after paralysis or denervation, could induce terminal sprouting indirectly through an action on muscle fibers (English, 2003).

Two issues prompted us to reexamine the sprouting responses of CNTF−/− mice. First, Siegel et al. might have underestimated the sprouting competence of the mice. Because their experimental system induced only moderate sprouting even in wildtype mice, their conclusion relied to a large extent on a statistical assessment. Moreover, we have recently discovered that exogenously administered CNTF induces primarily intrasynaptic sprouting of terminals that remain dramatically trapped within the parental endplates (Wright et al., submitted for publication). This finding raises the possibility that the conventional evaluation of terminal sprouting, which is based solely on extrasynaptic growth, might underestimate the extent of sprouting.

Second, although terminal Schwann cells (tSCs) have been strongly implicated in terminal sprouting (Son et al., 1996, Kang et al., 2003, Koirala et al., 2003), whether sprouting defects in CNTF null mice are due to abnormal reactivity of tSCs has not been addressed. Indeed, tSCs become reactive in response to paralysis or denervation (Reynolds and Woolf, 1992), and extend processes that appear to induce and guide terminal sprouts from innervated- to denervated muscle fibers (Son and Thompson, 1995a, Ko and Chen, 1996, Lubischer and Thompson, 1999, O'Malley et al., 1999, Love et al., 2003, Tam and Gordon, 2003b). Schwann cells are also the only cells in the peripheral nervous system that are known to express CNTF (Stockli et al., 1989, Friedman et al., 1992, Rende et al., 1992, Sendtner et al., 1992). We therefore were attracted by the possibility that nerve terminals in CNTF−/− mice fail to sprout because tSCs fail to extend processes. Here, we show that, in contrast to the earlier report, CNTF is dispensable for the reactive plasticity of both motor neurons and tSCs, and that compensatory reinnervation by axonal sprouts proceeds normally in CNTF−/− mice after nerve injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Two month-old female mice with homogeneous disruption of the Cntf gene (Masu et al., 1993) and age-matched wild type (+/+) controls (C57BL/6; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used. Three animals were typically used in each experimental group. CNTF null (−/−) mice reared in a colony maintained at the Drexel University College of Medicine (DUCOM) were routinely genotyped by PCR analysis (Masu et al., 1993) and the genotype of all mice used in the present experiments was additionally confirmed. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with DUCOM's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

CNTF and BoTX administration

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (120 mg/kg; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Inc., Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (8 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, Iowa). To evaluate the reactivity of nerve terminals and tSCs to exogenously applied CNTF, recombinant rat CNTF (200 ng/ 25g mouse; R& D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), dissolved in 50μl vehicle containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), was injected subcutaneously over the right Levator auris longus (LAL) muscle under aseptic conditions. CNTF was administered every 12 hours, for up to 14 days. To assess reactivity of nerve terminals and tSCs to muscle paralysis, botulinum toxin A (BoTX; 2.0 pg/ 25g mouse; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO), dissolved in 50μl sterile saline, was injected subcutaneously over the right LAL muscle. Similar dosages of BoTX have been shown to induce complete paralysis of mouse LAL muscles for up to four weeks (Juzans et al., 1996, Angaut-Petit et al., 1998). In order to assure prolonged paralysis of LAL muscles, BoTX was administered every fourth day for up to 14 days.

Partial or complete denervation

To examine sprouting and reinnervation after partial denervation, the L4 and L5 spinal roots were exposed under aseptic conditions and the right L4 spinal root was transected to denervate extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles by ca. 80% (Albani et al., 1988, Tam et al., 2001). The proximal segment of the transected L4 root was tied with 10.0 suture and the distal segment reflected laterally to prevent reinnervation by L4 axons. Fourteen days after partial denervation, mice were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (300mg/Kg; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and EDL muscles were harvested for immunocytochemistry. To study CNTF expression in denervated tSCs, sciatic nerve was exposed proximal to the branching of the sural nerve, transected and the proximal nerve stump was ligated with 7-0 suture to prevent regeneration. Mice were euthanized 10 days later and EDL muscles ipsilateral to the lesion were harvested for immunohistochemistry. Tails were collected from all euthanized CNTF−/− mice and processed for PCR verification of genotypes.

Immunohistochemistry

The procedures used for immunostaining have been described in detail previously (Burns et al., 2007). Briefly, muscles were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) containing 0.1M glycine. Muscles were then incubated for 15 minutes with rhodamine-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (Molecular Probes, St. Louis, MO), diluted 1:200 in PBS, to label acetylcholine receptors (AChRs). The muscles were then permeabilized in −20°C methanol for 5 min and blocked for 1 hour in PBS containing 0.2% Triton and 2% BSA. The muscles were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C in a cocktail of primary antibodies diluted in the blocking solution. Axons and nerve terminals were labeled with mouse monoclonal antibodies to neurofilaments (SMI 312; Sternberger Monoclonals, Baltimore, MD), diluted 1:1000 and to a synaptic vesicle protein, SV2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa), diluted 1:10. Schwann cells in intact muscles were labeled with rabbit anti-cow S-100 polyclonal antibody (Dako, Carpentaria, CA), diluted 1:400. To label Schwann cells in denervated muscles, we used S100 antibody in combination with an antibody to p75 (Chemicon, Billerica, MA). Endogenous CNTF was labeled with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to CNTF (Sendtner et al., 1992). To determine CNTF immunoreactivity in denervated tSCs with simultaneous labeling of axons, SCs and AChRs, we used the Kosmos mouse line in which Schwann cells are genetically labeled with eGFP (Zuo et al., 2004). After incubation with the primary antibodies, muscles were rinsed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies in the blocking solution, for 1 hour at room temperature. The secondary antibody for monoclonal antibodies was fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) or Alexa-Fluor 350 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), diluted 1:200. The secondary antibody for polyclonal antibodies was Alexa-Fluor 647 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), diluted 1:200. After incubation with the secondary antibodies, the muscles were rinsed in PBS, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and stored at −20°C.

Analysis

We analyzed nerve terminal and tSC responses to exogenous CNTF, paralysis and partial denervation. For all experiments, muscles were examined in wholemount preparations by blinded observers who were unaware of the muscle genotype. In CNTF or BoTX-treated LAL muscles, sprouting competence was determined by the percentage of the junctions with terminal sprouts and by the number and length of terminal sprouts extended from each junction. Terminal sprouts were considered extraterminal if they had extended beyond the boundary of the AChR label and their tips were positioned extrasynaptically on fiber surface; they could be as short as 1 μm. Terminal sprouts were considered intraterminal if their growth was confined within the parental synapse area. The length of extraterminal sprouts was determined by measuring the distance from the AChR label to the most distant points of the sprouts and included the secondary and tertiary branches of primary sprouts.

In partially-denervated EDL muscles, each junction was first categorized as: (1) normally innervated by original axon, (2) completely denervated, (3) denervated but reinnervated by terminal sprout(s), or (4) denervated but reinnervated by nodal sprout(s). At early times after partial denervation (i.e., 2 weeks), several features distinguished endplates reinnervated by nodal or terminal sprouts from the endplates innervated by their original axons (i.e., those spared the partial denervation). These characteristics of reinnervated endplates included thinner diameter of preterminal axons, varicosities along the length of preterminal axons, and the often incomplete occupation of AChR clusters by these axons. In addition, these axons occasionally could be traced to the node of Ranvier from which they originated. Junctions innervated by original axons from the intact L5 spinal root were further examined both for tSC processes acting as bridges to a denervated end plate and for terminal sprouts growing on these bridges. The frequency of tSC bridges between innervated and denervated endplates was determined by counting the number of junctions linked by a bridge/ number of all endplates examined. Muscles were analyzed using an Olympus BX61 widefield fluorescence microscope equipped with an integrating, cooled CCD camera (ORCA-ER, Hamamatsu, Japan) connected to a PC equipped with a frame grabber and running image analysis software (Olympus analySIS, Melville, NY). High-resolution confocal images were obtained with a Leica Plan Apo 63X oil objective (1.4NA) on a Leica TCS 4D confocal microscope (Heidelberg, Germany). Leica TCS-NT acquisition software was used to reconstruct z-series images into maximum intensity projections. Multipanel images presented in the figures were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired Student t tests were performed to compare the extent of sprouting in wildtype versus knockout mice, using StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Inc. Berkley, CA). Differences were considered statistically significant when p <0.05. All data are presented as means ± SEM.

RESULTS

Nerve terminal reactivity to exogenous CNTF in CNTF−/− mice

To determine the responses of motor nerve terminals in CNTF−/− mice to exogenously applied CNTF, we initially chose to study Lateral gastrocnemius (LG) muscles, which earlier investigators had also examined (Siegel et al., 2000). The extent of terminal sprouting in wildtype CNTF+/+ LG muscles, as measured by the percentage of the junctions with sprouts, was limited, similar to the ca. 10% of total junctions that were observed to sprout in CNTF−/− LG muscles in the earlier study. Notably, however, the junctions with sprouts were preferentially located near the injection sites, indicating that exposure of the muscle junctions to CNTF had been limited or uneven (data not shown; see Discussion). This had also been noted in a previous analysis of CNTF-treated Gluteus muscles (Gurney et al., 1992). We subsequently found that CNTF subcutaneously applied to LAL, a thin, superficial muscle at the back of the head with well-recognized advantages for pharmacological studies (Angaut-Petit et al., 1987, Lanuza et al., 2002), could induce nearly all of the nerve terminals to sprout. Moreover, most of these terminal sprouts grew intrasynaptically (e.g., Fig. 1B; Wright et al., submitted for publication). In the present study we therefore used LAL muscles to analyze motor nerve terminal and tSC reactivity in mice lacking CNTF.

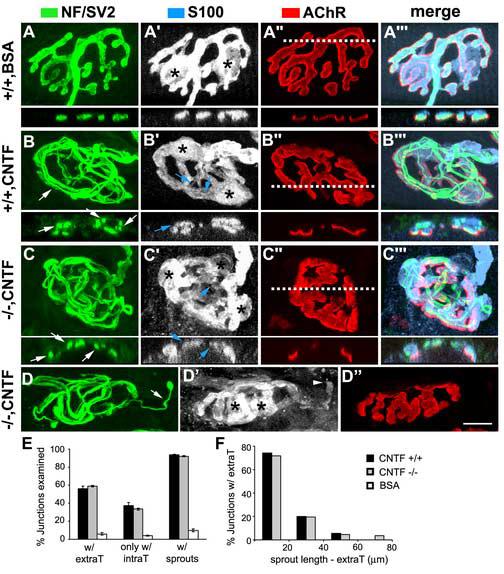

Figure 1.

Nerve terminals and tSCs in CNTF−/− mice react normally to exogenous CNTF. High magnification confocal images of junctions from wildtype or CNTF−/− LAL muscles treated with BSA or CNTF for 14 days. Preterminal and terminal axons were immunolabeled for neurofilaments and a synaptic vesicle protein, SV2 (Green), Schwann cells were labeled for S100 (Blue), and muscle AChRs were labeled for α-bungarotoxin (Red). Insets of Figures 1A-C”’ show z-y optical sections through the horizontal axis indicated by the dotted line in the AChR panels. (A-A”’), A control junction treated with BSA. Terminal branches are covered by tSCs and tSC processes, which are precisely apposed to AChR clusters. Stars point to cell bodies of tSCs, as also in Fig. 1B', C', D'. (B-B”’), A typical junction from a CNTF+/+ muscle treated with CNTF displaying no extrasynaptic growth of terminal sprouts. Bundles of intraterminal sprouts (e.g., white arrows in Fig. 1B) extend along parental branches of axon terminals and tSCs. Extrasynaptic, but not intrasynaptic (e.g., blue arrows in Fig. 1'), growth of new tSC processes is also rare. (C-C”’) and (D-D”’), Representative junctions from CNTF−/− muscles treated with CNTF displaying vigorous intrasynaptic growth of terminal sprouts and tSC processes. As in wildtype junctions treated with CNTF, extraterminal sprouts/tSC processes are rare or absent. An arrowhead in Fig. 1D' points to a tSC process that extends in association with a terminal sprout (arrow in Fig. 1D). (E), Percent distribution of junctions with terminal sprouts. In muscles of both genotypes, nearly 90% of nerve terminals sprout in response to exogenous CNTF. Substantial numbers of junctions responded with only intrasynaptic growth of terminal sprouts. (F), Percent distribution of junctions with extraterminal sprouts of different length. The extent of terminal sprouting, measured by the length of extraterminal sprouts, does not differ in CNTF+/+ and −/− muscles. Data were collected from 206 and 249 en face junctions taken from 3 LAL muscles each for CNTF+/+ and −/− mice, respectively. extraT, extraterminal sprouts; intraT, intraterminal sprouts. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 10 μm

In CNTF+/+ muscles treated with vehicle solutions for 14 days (n=3 muscles), each junction elaborated fine branches that were covered tightly by tSCs and their processes (Fig. 1A-A”’). The spatial configuration of both terminal branches and tSC processes closely replicated the branching patterns of postsynaptic AChR clusters, except in the area occupied by tSC cell bodies (e.g., Fig. 1A'; stars). In CNTF+/+ muscles treated with CNTF for 14 days (n=3 muscles), numerous thin axon profiles within or immediately adjacent to the synaptic region were observed across the entire surface of LAL muscles. Importantly, numerous junctions elaborated terminal sprouts that grew only intrasynaptically and were dramatically trapped within parental synapses (Fig. 1B-B”’). These junctions with only intraterminal sprouts represented ca. 37.5 ± 3.3% of the junctions and, if these junctions are included together with those elaborating extraterminal sprouts (56.3 ± 2.7% junctions), then the percentage of the junctions with terminal sprouts reached nearly 93.7 ± 0.6% of the total junctions examined (Fig. 1E; n=206 en face junctions). Similarly, in the CNTF−/− muscles treated with CNTF for 14 days (n=3 muscles), numerous junctions formed only intraterminal sprouts (Fig. 1C-C”’, 33.4 ± 1.2% of 249 en face junctions) and intrasynaptic sprouts predominated even in junctions that also elaborated extraterminal sprouts (Fig. 1D-D”; arrow points to a extraterminal sprout). When we counted the junctions displaying either intra- or extraterminal sprouts or both, the percentage of the nerve terminals in CNTF−/− muscles that sprouted in response to exogenous CNTF was 92.2 ± 0.8% of total junctions examined, almost the same as in CNTF+/+ muscles (Fig. 1E; p = 0.20, Student's t test). We also found no difference in the length of extraterminal sprouts between the CNTF+/+ and −/− muscles (Fig. 1F). Thus, terminal sprouting induced by exogenously applied CNTF in CNTF−/− mice was indistinguishable either qualitatively or quantitatively from that elicited in wildtype mice.

tSC reactivity to exogenous CNTF in CNTF−/− mice

We also found no differences in the reactions of tSCs to exogenous CNTF in CNTF+/+ and −/− mice. In muscles of both genotypes treated with CNTF for 14 days, tSCs extended new processes that grew along with intraterminal sprouts, as evidenced by intrasynaptic tSC labeling that overlapped with intraterminal sprouts but not with AChR clusters (Fig. 1B', C'; e.g., blue arrows). While intrasynaptic growth of new tSC processes was profuse, tSC processes rarely extended extrasynaptically either independently of terminal sprouts (Fig. 1B', C') or in advance of extraterminal sprouts (e.g., arrowhead in Fig 1D'; note the congruent growth of an extraterminal sprout and a tSC process).

Nerve terminal and tSC reactivity to acute paralysis in CNTF−/− mice

In response to the blockage of synaptic transmission, motor nerve terminals sprout (Duchen and Strich, 1968) and grow in association with tSC processes that often lead their extrasynaptic growth (Son and Thompson, 1995a). We first examined LAL muscles treated for 4 days with Botulinum toxin-A (BoTX) to assess early responses of nerve terminals and tSCs in CNTF−/− muscles to paralysis. Contrary to the earlier study (Siegel et al., 2000), we found no evidence of abnormal initiation of terminal sprouting or reactivation of tSCs in CNTF−/− muscles. First, as in CNTF+/+ muscles, terminal sprouts in CNTF−/− muscles grew primarily extrasynaptically (e.g., Fig. 2B: arrows) and were observed at ca. 29.4 ± 2.3% junctions (Fig. 2C; n=121 junctions, 3 muscles). Second, junctions with terminal sprouts in CNTF−/− muscles, as in CNTF+/+ muscles, typically elaborated 1-3 extraterminal sprouts (Fig. 1D). Third, the average length of the terminal sprouts in CNTF−/− muscles was also similar to that in CNTF+/+ muscles (Fig. 1E; 7.1 ± 0.2 μm vs. 8.0 ± 0.7 μm, respectively). Fourth, all terminal sprouts in CNTF−/− muscles were associated with tSC processes of equal or even longer length, as in CNTF+/+ muscles (Fig. 2A', B'; arrowheads). Fifth, tSCs in CNTF−/− muscles were reactive and extended processes independently of axons (Fig. 2A', B'; arrows). Thus, sprouting of nerve terminals and reactivation of tSCs are initiated normally in CNTF−/− mice.

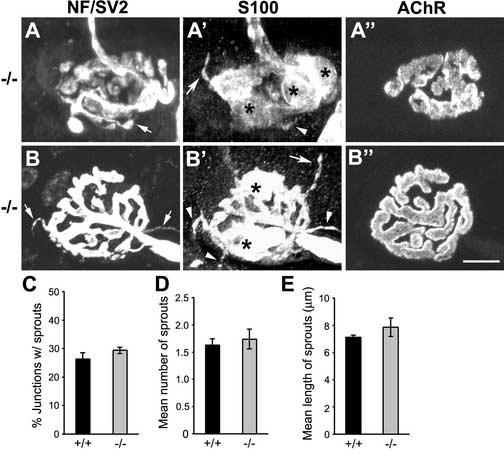

Figure 2.

Nerve terminals and tSCs in CNTF−/− mice react normally to acute paralysis. (A-A”) and (B-B”), Confocal images of representative junctions from CNTF−/− LAL muscles paralyzed for 4 days with BoTX. Muscles were labeled as described in Fig. 1. Short terminal sprouts (arrows in A, B) extend extrasynaptically in association with tSC processes that grow in advance of terminal sprouts (arrowheads in A', B') or independently of axons (arrows in A', B'). In addition, CNTF+/+ and −/− muscles show no difference in the percent distribution of junctions with sprouts (C), the average number of extraterminal sprouts extended from those junctions (D), or the average length of extraterminal sprouts (E). Stars in A' and B' point to cell bodies of tSCs. Data were collected from 114 and 121 en face junctions taken from 3 LAL muscles of CNTF+/+ or −/− mice. Scale bar, 10 μm

Nerve terminal and tSC reactivity to prolonged paralysis in CNTF−/− mice

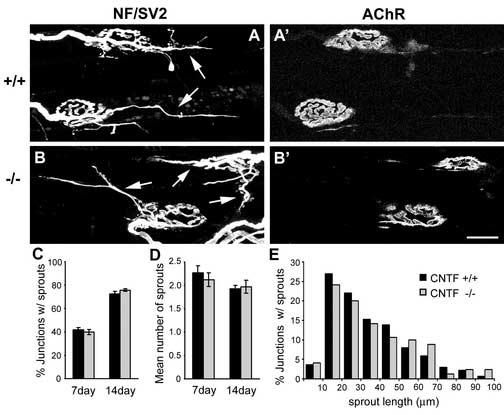

To test the possibility that terminal sprouting is initiated normally in paralyzed CNTF−/− muscles but that the sprouts are then retracted or fail to elongate, we extended our analysis to LAL muscles paralyzed by BoTX for longer periods of time. The extent of terminal sprouting in CNTF−/− muscles at the 7th and 14th day of paralysis, was indistinguishable from that evoked at the same days in CNTF+/+ mice; similar numbers of junctions in CNTF+/+ and −/− muscles elaborated extraterminal sprouts and the number and length of these sprouts were also similar (Fig. 3C-E). For example, in the CNTF−/− muscles paralyzed for 14 days (n=3 muscles, 109 en face junctions), lengthy extraterminal sprouts (arrows in Fig. 3B; see Fig. 3A for sprouts in wildtype muscles) were as frequent as in CNTF+/+ muscles (Fig. 3C; ca. 2 sprouts extended from nearly 80% junctions in LAL muscles of both genotypes; n=3 CNTF+/+ muscles, 120 en face junctions). In addition, terminal sprouts in CNTF−/− muscles were about the same length as those in CNTF+/+ muscles (Fig. 3E; average 31.89 μm and 36.29 μm for CNTF+/+ and −/− mice respectively; p = 0.08, students t test). We also observed no evidence of abnormal responses by tSCs; they often led terminal sprouts, although tSC processes not associated with terminal sprouts were rare in muscles of both genotypes (data not shown). Collectively, these results show that nerve terminals and tSCs in CNTF−/− mice react normally to the loss of activity (i.e., paralysis) and that they elaborate extensive new cellular processes.

Figure 3.

Motor nerve terminals in CNTF−/− mice sprout extensively in response to prolonged paralysis. (A, A'), Representative junctions of wildtype muscles paralyzed for 14 days displaying lengthy extraterminal sprouts (e.g., arrows). (B, B'), Representative junctions of CNTF−/− muscles paralyzed for 14 days displaying lengthy extraterminal sprouts (e.g., arrows). (C), Percent distribution of junctions with sprouts. Nearly 80% of nerve terminals in both CNTF +/+ and −/− muscles sprout by 14 days after paralysis. (D), Average number of terminal sprouts extended in CNTF+/+ or −/− muscles paralyzed for 7 or 14 days. (E), Percent distribution of junctions with extraterminal sprouts of different length in muscles paralyzed for 14 days. The length of terminal sprouts is similar in CNTF+/+ and CNTF−/− muscles. n=177, 205 junctions for 3 CNTF+/+ or −/− muscles paralyzed for 7 days; n=109, 120 junctions for 3 CNTF+/+ or −/− muscles paralyzed for 14 days. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Scale bar, 20 μm

Terminal sprouting and compensatory reinnervation in CNTF−/− mice after partial denervation

Siegel et al., (2000) also reported that partial denervation did not elicit terminal sprouting in CNTF−/− mice. When a portion of the motor innervation in a muscle is disrupted by partial denervation, spared motor neurons sprout at nodes of Ranvier and at nerve terminals (cf., Hoffman, 1950, Brown and Ironton, 1978) and substantially reinnervate the denervated muscle fibers. Preterminal- and terminal Schwann cells serve as a growth substrate for the nodal sprouts, which guide them to the original endplates of denervated muscle fibers (Son and Thompson, 1995b, Koirala et al., 2000). In addition, tSC processes extending from denervated endplates contact intact nerve terminals, forming ‘tSC bridges’ that induce and guide terminal sprouts to denervated endplates (Son and Thompson, 1995a, Love et al., 2003, Tam and Gordon, 2003b). To test if terminal sprouting indeed cannot be elicited in CNTF−/− muscles and if an abnormal response of tSCs correlates with the sprouting defect, we transected L4 spinal roots and studied EDL muscles that were extensively denervated by the procedure (cf., Albani et al., 1988, Tam et al., 2001; see Methods).

Contrary to the report of Siegel et al., (2000), we found significant sprouting of intact nerve terminals in partially denervated muscles of CNTF−/− mice. At 14 days after L4 root transection, ca. 50% of intact endplates (i.e., endplates innervated by L5 axons spared by L4 root transection) elaborated 1-3 terminal sprouts (Table 1; n=3 each for muscles of both genotypes). In addition, these terminal sprouts frequently reinnervated adjacent denervated endplates, as in wildtype mice (Fig. 4A; white arrow), and appeared to be guided by tSC bridges (Fig. 4B; black arrows). Additional comparisons also revealed no significant difference between the CNTF+/+ and −/− muscles in reinnervation of denervated muscle fibers by terminal sprouts, or in the ability of tSCs to form ‘tSC bridges’ (Table 1; p = 0.6, p=0.4, respectively, Student's t test).

Table 1.

Compensatory sprouting in CNTF−/− muscles in response to partial denervation

| Endplates examined |

Innervated w/ terminal sprouts (%) |

Endplates w/ tSC Bridges (%)d |

Reinnervated Endplates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innervateda | Denervatedb | Reinnervatedc | terminal sprouts (%) |

nodal sprouts (%) |

|||

| CNTF +/+ | 99 | 13 | 144 | 42.8 ± 7.3 | 30.1 ± 2.6 | 22.5 ± 6.1 | 83.7 ± 3.4 |

| CNTF −/− | 110 | 22 | 153 | 55.9 ± 3.4 | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 25.6 ± 1.7 | 84.0 ± 1.3 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 muscles each for CNTF+/+ and −/− animals partially denervated for 14 days by L4 transection.

Intact endplates spared by L4 transection.

Denervated endplates remaining completely devoid of axonal contact.

Denervated endplates reinnervated by nodal and/or terminal sprouts.

The percentage of all endplates examined (i.e., innervated and denervated) linked by tSC bridges.

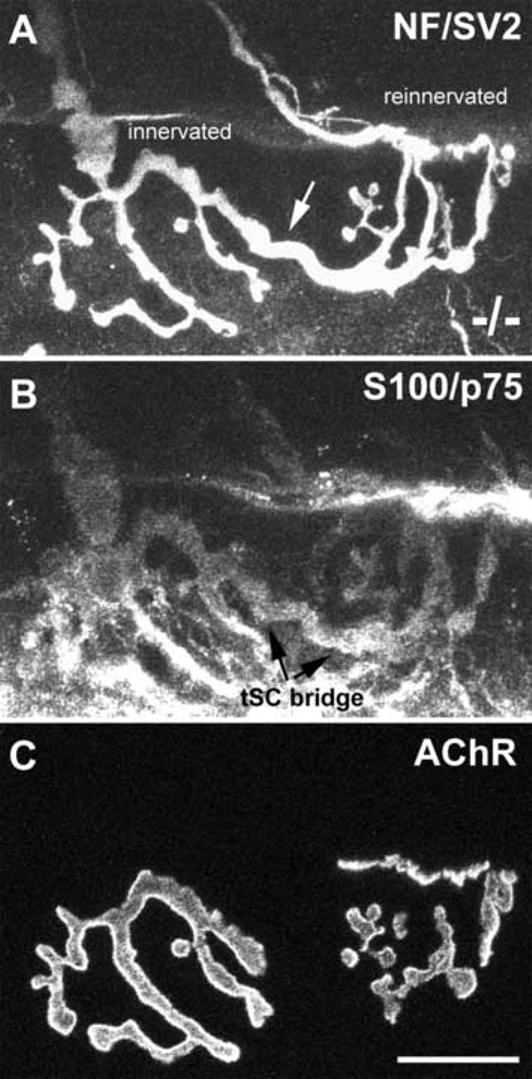

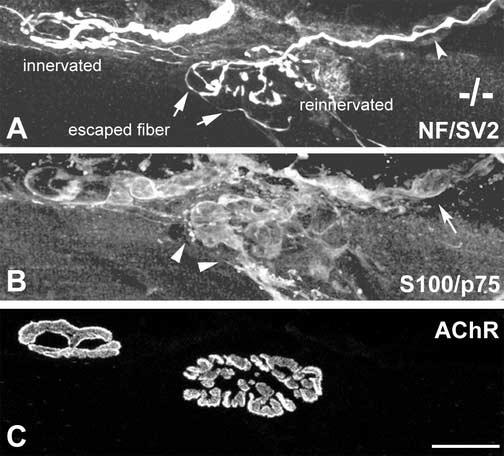

Figure 4.

Compensatory reinnervation by terminal sprouts and tSC bridges proceeds normally in CNTF−/− mice. Confocal image of an innervated and a reinnervated endplate in CNTF−/− muscles linked by a terminal sprout (A; white arrow) and a tSC bridge (B; black arrows). Muscles were partially denervated for 14 days and labeled as described in Fig. 1, except that p75 antibody was used together with S100 antibody to label both quiescent and reactive Schwann cells. Note that the terminal sprout that connects the two endplates (C) is associated with a tSC bridge, suggesting normal induction and guidance of terminal sprouts by tSCs in CNTF−/− muscles. Scale bar, 20 μm

Because we prevented regeneration of the transected L4 spinal axons, we were able to compare reinnervation by nodal sprouting in CNTF+/+ and −/− mice. As in the partially denervated wildtype EDL muscles, thin axonal profiles grew along preterminal SCs in CNTF −/− muscles and reoccupied the old synaptic sites of denervated muscle fibers (Fig. 5A; arrowhead). As shown previously in the rat (Son and Thompson, 1995b), these nodal sprouts appeared to continue to grow along tSC processes (Fig. 5B; arrowheads) and elaborated axonal processes beyond synaptic sites (‘escaped fibers’; Fig. 5A, arrows; cf., Gutmann and Young, 1944). Quantitative analysis also showed that reinnervation of denervated muscle fibers by nodal sprouting proceeded normally in CNTF−/− muscles and was as extensive as in CNTF+/+ muscles (Table 1). Taken together, these data show that partial denervation induces both nodal and terminal sprouting whether CNTF is present or not, and that reinnervation by the compensatory sprouting proceeds normally with the assistance of tSCs in CNTF−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Compensatory reinnervation by nodal sprouts proceeds normally in CNTF−/− mice. Muscles were partially denervated for 14 days and labeled as in Fig. 4. A nodal sprout (A; arrowhead) that extended along the preterminal SCs (B, arrow) innervates a previously denervated endplate (C, right endplate). The nodal sprout continues to grow along tSC processes (B, arrowheads), and elaborates an ‘escaped’ fiber (e.g., arrows in A) that extends beyond the synaptic boundary. These features are typical of reinnervation of wildtype muscles after partial denervation. Note that nodal sprouts are easily distinguishable from myelinated axons innervating intact endplates (A, a thick axon innervating the left endplate) both by axon thickness and by the extent of terminal arborization. Scale bar, 20 μm

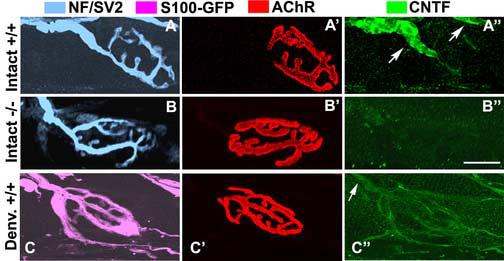

CNTF expression at the neuromuscular junction

Although CNTF is known to be expressed in myelinating Schwann cells (Stockli et al., 1989, Sendtner et al., 1992), whether tSCs express it remains undetermined. We used an antibody specific to CNTF (Sendtner et al., 1992) to examine local expression of CNTF at intact and denervated junctions. At intact junctions of wildtype mice, CNTF immunoreactivity was observed in myelinating SCs but not in tSCs, nerve terminals or muscle fibers (Fig. 6A”; arrows point to preterminal, myelinating SCs). As expected, we detected no immunoreactivity at junctions of the CNTF−/− mice used in the present study (Fig. 6B”). In order to simultaneously label axons, tSCs, AChRs and CNTF at denervated NMJs, we used a transgenic mouse line in which Schwann cells are genetically labeled with eGFP (Zuo et al., 2004). We observed faint or no CNTF immunoreactivity in reactive tSCs at the junctions completely denervated for 10 days (Fig. 6C”; axons are not shown). CNTF expression was also reduced in myelinating SCs, as noted in earlier studies (Sendtner et al., 1992), and barely detectable in some of them (Fig. 6C; arrow). Thus, CNTF expression in tSCs is absent or negligible during the period of extensive sprouting of nerve terminals. These results provide further support for our conclusion that CNTF is dispensable for terminal sprouting, for tSC reactivation, and for compensatory reinnervation in paralyzed or denervated muscles.

Figure 6.

Quiescent and reactive tSCs express little if any CNTF. Confocal images of intact or denervated junctions of CNTF+/+ (A-A”, C-C”) and CNTF−/− EDL muscles (B-B”). For 4-color labeling of denervated muscles, a transgenic mouse line expressing GFP selectively in Schwann cells was used (see Methods). (A-A”), Representative junction from intact, wildtype muscle displaying CNTF expression only in myelinating Schwann cells (A”, arrows). (B-B”), A junction from intact, CNTF−/− muscle verifying complete elimination of CNTF in the CNTF null mice. (C-C”), A junction from a CNTF+/+ EDL muscle, completely denervated for 10 days, displays faint if any CNTF labeling in tSCs and their processes. Image of axons were omitted. Note also marked reduction of CNTF expression in some of the denervated myelinating Schwann cells (e.g., C”, arrow). Scale bar, 20 μm

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we observed that motor nerve terminals and tSCs in CNTF−/− mice reacted normally to three different stimuli: exogenous CNTF, paralysis and partial denervation. Muscles from CNTF+/+ and −/− mice revealed no differences in the extent of terminal sprouting, as assessed by the proportion of junctions with sprouts, or in the number and length of the sprouts. tSCs in CNTF−/− mice were also reactive to these stimuli and elaborated processes consistent with the proposed roles of tSCs in terminal sprouting and compensatory reinnervation. Indeed, reinnervation of denervated endplates by terminal or nodal sprouting proceeded normally in CNTF−/− mice. We also observed little if any expression of CNTF at neuromuscular junctions during the period of active terminal sprouting. These results lead us to conclude that endogenous CNTF is not required for induction of terminal sprouting, reactivation of tSCs or compensatory reinnervation after nerve injury. Together with other findings from our laboratory (see below), these results support the idea that compensatory sprouting in adult muscles is induced primarily by contact-mediated mechanisms.

We observed that, in CNTF−/− mice, almost 90% of terminals in LAL muscles sprout in response to exogenous CNTF and that 80% sprout in response to paralysis. In addition, ca. 56% of intact terminals in EDL muscles of the null mice sprout in response to partial denervation. These results contradict the prior analysis of CNTF−/− mice by Siegel et al. (2000), which reported sprouting at only about 10% of terminals in LG muscles in response to any of the sprouting stimuli. One explanation for the discrepancy may be that the previous investigators studied a different line of CNTF−/− mice, which was not available to us (DeChiara et al., 1995). However, the CNTF null mice used in the present study (Masu et al., 1993) share the C57BL/6 background of the line used by Siegel et al., and display similar motor neuron deficits (Masu et al., 1993, DeChiara et al., 1995). The discrepancy is also unlikely to be attributable to variable sprouting competence among muscles examined in the two studies (Brown et al., 1980, Prakash et al., 1999, Pun et al., 2002, De Winter et al., 2006, Burns et al., 2007), because LAL, EDL and LG muscles are all fast-twitch muscles. Its response to paralysis also suggests that LAL is, like LG, a Delayed-synapsing muscle with robust sprouting capability (Pun et al., 2002).

Analysis of the earlier report suggests an alternative explanation. For example, Siegel et al. observed moderate if any sprouting even in the wildtype LG muscles: ca. 20% junctions with sprouts after paralysis and 23% after partial denervation (no data with exogenous CNTF; Siegel et al., 2000). On the other hand, they found that sprouts formed spontaneously at ca. 10% of LG junctions in unoperated CNTF+/+ or −/− mice. We believe that the relatively low incidence of sprouting in the treated wildtype muscles and the high incidence of spontaneous sprouting in untreated muscles indicate that the LG muscles and/or experimental conditions that Siegel et al. used did not provide an optimal system for comparative analysis of sprouting. Results of our preliminary experiments support this notion. We found that CNTF subcutaneously applied to LG muscles, using the protocol that elicited robust sprouting in LAL muscles, evoked little if any sprouting. Moreover, junctions with sprouts were restricted to the immediate vicinity of the injection sites, suggesting that exposure of LG junctions to CNTF was limited (see also Gurney et al., 1992). In contrast, consistent with the recognized advantages of LAL muscles for pharmacological studies (Angaut-Petit et al., 1987, Lanuza et al., 2002), we observed that CNTF injected between the subdermal connective tissue and the LAL fascia, but not CNTF injected subcutaneously into LG or other hindlimb muscles, formed a local subdermal swelling that persisted for at least one hour before vascular reabsorption (data not shown; cf., Lanuza et al., 2001).

Our conclusions, terminal sprouting and tSC activation proceed normally in CNTF−/− mice, are also in line with our recent finding that exogenously applied CNTF and BoTX induce qualitatively distinct sprouting (Wright et al., submitted for publication). Whereas CNTF initiates sprouting randomly on the superficial surface of terminal branches and leads to extensive intrasynaptic growth of terminal sprouts, paralysis induced by BoTX initiates topological sprouting exclusively along the perimeter of terminal branches in direct contact with muscle fiber membranes. As also shown in the present study, the terminal sprouts induced by paralysis extend extrasynaptically and display little if any intrasynaptic growth. These observations suggest that paralysis induces terminal sprouting by means of surface-bound molecules that mediate local interactions between nerve and muscle membranes, and that diffusible factors such as CNTF are unlikely to mediate paralysis-elicited sprouting.

It is also important to note that, after partial denervation, tSC processes extending from denervated endplates appear to induce terminal sprouting by contact-mediated mechanisms (Son and Thompson, 1995a; Trachtenberg and Thompson, 1997; Son YJ, Bhagat S, Ketschek S., unpublished observations). Although diffusible factors released from degenerating nerves and/or denervated muscle fibers may act at a distance to elicit some sprouts (i.e., those not associated with tSC bridges), these sprouts are not sufficient to reinnervate denervated endplates (Son and Thompson, 1995a). Hence, it seems possible that surface-bound molecules with neuritogenic activity primarily induce terminal sprouting, which provides a unifying mechanism for both paralysis- and denervation-elicited sprouting. Candidates include cell adhesion molecules such as NCAM and tenascin-C (Booth et al., 1990, Cifuentes-Diaz et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1999, Walsh et al., 2000; but see Moscoso et al., 1998).

Our conclusion that endogenous CNTF is dispensable for motor nerve sprouting, however, does not challenge the neuroprotective and myoprotective effects of CNTF or its therapeutic potential for degenerative neuromuscular diseases (cf., Sendtner, 1996, Vergara and Ramirez, 2004, Pun et al., 2006). Exogenous CNTF, for instance, could be useful to promote muscle reinnervation by accelerating axonal regeneration along peripheral nerves (cf., Sahenk et al., 1994, Zhang et al., 2004) or by enhancing compensatory sprouting. In support of this notion, we found that, whereas exogenous CNTF alone induced terminal sprouts that are trapped intrasynaptically (cf. Fig. 1), when combined with a treatment that renders muscle surface supportive for axonal extension, CNTF elicited exceptionally robust extrasynaptic growth of terminal sprouts (Wright et al., submitted for publication). Spontaneous reinnervation by compensatory sprouting after nerve injury is limited, and rarely restores motor innervation to extensively denervated muscles (Thompson and Jansen, 1977, Brown and Ironton, 1978, Luff et al., 1988, Gordon et al., 1993, Rafuse and Gordon, 1996). Therefore, increasing the growth potential of spared or regenerating axons with CNTF while promoting formation of tSC bridges or axonal growth along muscle surface may provide a strategy for effectively enhancing recovery of motor function after nerve injury.

The present data emphasize the importance of analyzing sprouting competence under the proper experimental conditions and support the idea that compensatory sprouting in adult muscles is induced by contact-mediated mechanisms. Despite identification of numerous molecules eliciting sprouting, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive (recent reviews in English, 2003, Kang et al., 2003, Koirala et al., 2003, Tam and Gordon, 2003a). Reactive sprouting of spared circuits is also common after brain and spinal cord injuries (cf., Raineteau and Schwab, 2001, Carmichael, 2006, Deller et al., 2006). Focused searches for surface-bound molecules with neuritogenic activity may prove productive, not only to identify physiological inducers of peripheral sprouting, but also to manipulate central sprouting to optimize its beneficial effects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Sendtner for providing CNTF null mice and anti-CNTF antibodies, and Wes Thompson for Kosmos mice. We also thank Tim Himes, John Houle, Alan Tessler, Srilatha Potluri for their critical reading of the manuscript, and Jiang Xu for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH NS45091 to Y.-J. S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Albani M, Lowrie MB, Vrbova G. Reorganization of motor units in reinnervated muscles of the rat. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988;88:195–206. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angaut-Petit D, Molgo J, Comella JX, Faille L, Tabti N. Terminal sprouting in mouse neuromuscular junctions poisoned with botulinum type A toxin: morphological and electrophysiological features. Neuroscience. 1990;37:799–808. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90109-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angaut-Petit D, Molgo J, Connold AL, Faille L. The levator auris longus muscle of the mouse: a convenient preparation for studies of short- and long-term presynaptic effects of drugs or toxins. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;82:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angaut-Petit D, Molgo J, Faille L, Juzans P, Takahashi M. Incorporation of synaptotagmin II to the axolemma of botulinum type-A poisoned mouse motor endings during enhanced quantal acetylcholine release. Brain Res. 1998;797:357–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth CM, Kemplay SK, Brown MC. An antibody to neural cell adhesion molecule impairs motor nerve terminal sprouting in a mouse muscle locally paralysed with botulinum toxin. Neuroscience. 1990;35:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90123-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Holland RL, Hopkins WG. Motor nerve sprouting. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1981;4:17–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Holland RL, Ironton R. Nodal and terminal sprouting from motor nerves in fast and slow muscles of the mouse. J. Physiol. 1980;306:493–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Ironton R. Sprouting and regression of neuromuscular synapses in partially denervated mammalian muscles. J. Physiol. 1978;278:325–348. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AS, Jawaid S, Zhong H, Yoshihara H, Bhagat S, Murray M, Roy RR, Tessler A, Son YJ. Paralysis elicited by spinal cord injury evokes selective disassembly of neuromuscular synapses with and without terminal sprouting in ankle flexors of the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;500:116–133. doi: 10.1002/cne.21143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of neural repair after stroke: making waves. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:735–742. doi: 10.1002/ana.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P, Grandes P. Nerve sprouting in innervated adult skeletal muscle induced by exposure to elevated levels of insulin-like growth factors. J. Cell. Biol. 1990;110:1307–1317. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P, Schneider C, Kiefer MC, Zapf J. Role of muscle insulin-like growth factors in nerve sprouting: suppression of terminal sprouting in paralyzed muscle by IGF-binding protein 4. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:893–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Diaz C, Velasco E, Meunier FA, Goudou D, Belkadi L, Faille L, Murawsky M, Angaut-Petit D, Molgo J, Schachner M, Saga Y, Aizawa S, Rieger F. The peripheral nerve and the neuromuscular junction are affected in the tenascin-C-deficient mouse. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 1998;44:357–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Winter F, Vo T, Stam FJ, Wisman LA, Bar PR, Niclou SP, van Muiswinkel FL, Verhaagen J. The expression of the chemorepellent Semaphorin 3A is selectively induced in terminal Schwann cells of a subset of neuromuscular synapses that display limited anatomical plasticity and enhanced vulnerability in motor neuron disease. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:102–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Vejsada R, Poueymirou WT, Acheson A, Suri C, Conover JC, Friedman B, McClain J, Pan L, Stahl N, Ip NY, Yancopoulos GD. Mice lacking the CNTF receptor, unlike mice lacking CNTF, exhibit profound motor neuron deficits at birth. Cell. 1995;83:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T, Haas CA, Freiman TM, Phinney A, Jucker M, Frotscher M. Lesion-induced axonal sprouting in the central nervous system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;557:101–121. doi: 10.1007/0-387-30128-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen LW, Strich SJ. The effects of botulinum toxin on the pattern of innervation of skeletal muscle in the mouse. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 1968;53:84–89. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1968.sp001948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English AW. Cytokines, growth factors and sprouting at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurocytol. 2003;32:943–960. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020634.59639.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Scherer SS, Rudge JS, Helgren M, Morrisey D, McClain J, Wang DY, Wiegand SJ, Furth ME, Lindsay RM, et al. Regulation of ciliary neurotrophic factor expression in myelin-related Schwann cells in vivo. Neuron. 1992;9:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90168-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi H, Belluardo N, Arenas E, Yamamoto Y, Casabona A, Persson H, Ibanez CF. Muscle-derived neurotrophin-4 as an activity-dependent trophic signal for adult motor neurons. Science. 1995;268:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.7770776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T, Yang JF, Ayer K, Stein RB, Tyreman N. Recovery potential of muscle after partial denervation: a comparison between rats and humans. Brain Res. Bull. 1993;30:477–482. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Yamamoto H, Kwon Y. Induction of motor neuron sprouting in vivo by ciliary neurotrophic factor and basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:3241–3247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03241.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann E, Young JZ. The re-innervation of muscle after various periods of atrophy. J. Anat. 1944;78:15–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman H. Local re-innervation in partially denervated muscle; a histophysiological study. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1950;28:383–397. doi: 10.1038/icb.1950.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juzans P, Comella JX, Molgo J, Faille L, Angaut-Petit D. Nerve terminal sprouting in botulinum type-A treated mouse levator auris longus muscle. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1996;6:177–185. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(96)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Tian L, Thompson W. Terminal Schwann cells guide the reinnervation of muscle after nerve injury. J. Neurocytol. 2003;32:975–985. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020636.27222.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CP, Chen L. Synaptic remodeling revealed by repeated in vivo observations and electron microscopy of identified frog neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1780–1790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01780.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koirala S, Qiang H, Ko CP. Reciprocal interactions between perisynaptic Schwann cells and regenerating nerve terminals at the frog neuromuscular junction. J. Neurobiol. 2000;44:343–360. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(20000905)44:3<343::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koirala S, Reddy LV, Ko CP. Roles of glial cells in the formation, function, and maintenance of the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurocytol. 2003;32:987–1002. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020637.71452.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YW, Gurney ME. Systemic injections of ciliary neurotrophic factor induce sprouting by adult motor neurons. Neuroreport. 1994;5:789–792. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199403000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanuza MA, Garcia N, Santafe M, Nelson PG, Fenoll-Brunet MR, Tomas J. Pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein and protein kinase C activity are involved in normal synapse elimination in the neonatal rat muscle. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;63(4):330–340. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010215)63:4<330::AID-JNR1027>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanuza MA, Garcia N, Santafe M, Gonzalez CM, Alonso I, Nelson PG, Tomas J. Pre- and postsynaptic maturation of the neuromuscular junction during neonatal synapse elimination depends on protein kinase C. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;67:607–617. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RE, Tartell PB, Karmody CS, Hunter DD. Association of adhesive macromolecules with terminal sprouts at the neuromuscular junction after botulinum treatment. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 1999;120:255–261. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love FM, Son YJ, Thompson WJ. Activity alters muscle reinnervation and terminal sprouting by reducing the number of Schwann cell pathways that grow to link synaptic sites. J. Neurobiol. 2003;54:566–576. doi: 10.1002/neu.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubischer JL, Thompson WJ. Neonatal partial denervation results in nodal but not terminal sprouting and a decrease in efficacy of remaining neuromuscular junctions in rat soleus muscle. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8931–8944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08931.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff AR, Hatcher DD, Torkko K. Enlarged motor units resulting from partial denervation of cat hindlimb muscles. J. Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1377–1394. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.5.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino RJ, Herbison GJ, Ditunno JF., Jr. Peripheral sprouting as a mechanism for recovery in the zone of injury in acute quadriplegia: a single-fiber EMG study. Muscle. Nerve. 1994;17:1466–1468. doi: 10.1002/mus.880171218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu Y, Wolf E, Holtmann B, Sendtner M, Brem G, Thoenen H. Disruption of the CNTF gene results in motor neuron degeneration. Nature. 1993;365:27–32. doi: 10.1038/365027a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier FA, Schiavo G, Molgo J. Botulinum neurotoxins: from paralysis to recovery of functional neuromuscular transmission. J. Physiol. Paris. 2002;96:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(01)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso LM, Cremer H, Sanes JR. Organization and reorganization of neuromuscular junctions in mice lacking neural cell adhesion molecule, tenascin-C, or fibroblast growth factor-5. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1465–1477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01465.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley JP, Waran MT, Balice-Gordon RJ. In vivo observations of terminal Schwann cells at normal, denervated, and reinnervated mouse neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurobiol. 1999;38:270–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash YS, Miyata H, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Inactivity-induced remodeling of neuromuscular junctions in rat diaphragmatic muscle. Muscle. Nerve. 1999;22:307–319. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199903)22:3<307::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun S, Santos AF, Saxena S, Xu L, Caroni P. Selective vulnerability and pruning of phasic motoneuron axons in motoneuron disease alleviated by CNTF. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:408–419. doi: 10.1038/nn1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun S, Sigrist M, Santos AF, Ruegg MA, Sanes JR, Jessell TM, Arber S, Caroni P. An intrinsic distinction in neuromuscular junction assembly and maintenance in different skeletal muscles. Neuron. 2002;34:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafuse VF, Gordon T. Self-reinnervated cat medial gastrocnemius muscles. I. comparisons of the capacity for regenerating nerves to form enlarged motor units after extensive peripheral nerve injuries. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;75:268–281. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineteau O, Schwab ME. Plasticity of motor systems after incomplete spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:263–273. doi: 10.1038/35067570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende M, Muir D, Ruoslahti E, Hagg T, Varon S, Manthorpe M. Immunolocalization of ciliary neuronotrophic factor in adult rat sciatic nerve. Glia. 1992;5:25–32. doi: 10.1002/glia.440050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds ML, Woolf CJ. Terminal Schwann cells elaborate extensive processes following denervation of the motor endplate. J. Neurocytol. 1992;21:50–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01206897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahenk Z, Seharaseyon J, Mendell JR. CNTF potentiates peripheral nerve regeneration. Brain Res. 1994;655:246–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendtner M. Neurotrophic factors for experimental treatment of motoneuron disease. Prog. Brain Res. 1996;109:365–371. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendtner M, Stockli KA, Thoenen H. Synthesis and localization of ciliary neurotrophic factor in the sciatic nerve of the adult rat after lesion and during regeneration. J. Cell Biol. 1992;118:139–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SG, Patton B, English AW. Ciliary neurotrophic factor is required for motoneuron sprouting. Exp. Neurol. 2000;166:205–212. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider WD, Harris GL. A physiological correlate of disuse-induced sprouting at the neuromuscular junction. Nature. 1979;281:69–71. doi: 10.1038/281069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son YJ, Thompson WJ. Nerve sprouting in muscle is induced and guided by processes extended by Schwann cells. Neuron. 1995a;14:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son YJ, Thompson WJ. Schwann cell processes guide regeneration of peripheral axons. Neuron. 1995b;14:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son YJ, Trachtenberg JT, Thompson WJ. Schwann cells induce and guide sprouting and reinnervation of neuromuscular junctions. Trends. Neurosci. 1996;19:280–285. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockli KA, Lottspeich F, Sendtner M, Masiakowski P, Carroll P, Gotz R, Lindholm D, Thoenen H. Molecular cloning, expression and regional distribution of rat ciliary neurotrophic factor. Nature. 1989;342:920–923. doi: 10.1038/342920a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam SL, Archibald V, Jassar B, Tyreman N, Gordon T. Increased neuromuscular activity reduces sprouting in partially denervated muscles. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:654–667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00654.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam SL, Gordon T. Mechanisms controlling axonal sprouting at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurocytol. 2003a;32:961–974. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020635.41233.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam SL, Gordon T. Neuromuscular activity impairs axonal sprouting in partially denervated muscles by inhibiting bridge formation of perisynaptic Schwann cells. J. Neurobiol. 2003b;57:221–234. doi: 10.1002/neu.10276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarabal O, Caldero J, Esquerda JE. Intramuscular nerve sprouting induced by CNTF is associated with increases in CGRP content in mouse motor nerve terminals. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;219:60–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CK, Broton JG, Calancie B. Motor unit forces and recruitment patterns after cervical spinal cord injury. Muscle. Nerve. 1997;20:212–220. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199702)20:2<212::aid-mus12>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson W, Jansen JK. The extent of sprouting of remaining motor units in partly denervated immature and adult rat soleus muscle. Neuroscience. 1977;2:523–535. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(77)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg JT, Thompson WJ. Nerve terminal withdrawal from rat neuromuscular junctions induced by neuregulin and Schwann cells. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6243–6255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06243.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Ramirez B. CNTF, a pleiotropic cytokine: emphasis on its myotrophic role. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2004;47:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh FS, Hobbs C, Wells DJ, Slater CR, Fazeli S. Ectopic expression of NCAM in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice results in terminal sprouting at the neuromuscular junction and altered structure but not function. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;15:244–261. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig A, Herrera AA. Sprouting and remodelling at the nerve-muscle junction. Prog. Neurobiol. 1986;27:251–291. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(86)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JF, Stein RB, Jhamandas J, Gordon T. Motor unit numbers and contractile properties after spinal cord injury. Ann. Neurol. 1990;28:496–502. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lineaweaver WC, Oswald T, Chen Z, Chen Z, Zhang F. Ciliary neurotrophic factor for acceleration of peripheral nerve regeneration: an experimental study. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2004;20:323–327. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-824891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Lubischer JL, Kang H, Tian L, Mikesh M, Marks A, Scofield VL, Maika S, Newman C, Krieg P, Thompson WJ. Fluorescent proteins expressed in mouse transgenic lines mark subsets of glia, neurons, macrophages, and dendritic cells for vital examination. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10999–11009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3934-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]