Abstract

This investigation was designed to evaluate the single-dose pharmacokinetics of itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) after intravenous administration to children at risk for fungal infection. Thirty-three children aged 7 months to 17 years received a single dose of itraconazole (2.5 mg/kg in 0.1-g/kg HP-β-CD) administered over 1 h by intravenous infusion. Plasma samples for the determination of the analytes of interest were drawn over 120 h and analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography, and the pharmacokinetics were determined by traditional noncompartmental analysis. Consistent with the role of CYP3A4 in the biotransformation of itraconazole, a substantial degree of variability was observed in the pharmacokinetics of this drug after IV administration. The maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) for itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD averaged 1,015 ± 692 ng/ml, 293 ± 133 ng/ml, and 329 ± 200 μg/ml, respectively. The total body exposures (area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h) for itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD averaged 4,922 ± 6,784 ng·h/ml, 3,811 ± 2,794 ng·h/ml, and 641.5 ± 265.0 μg·h/ml, respectively, with no significant age dependence observed among the children evaluated. Similarly, there was no relationship between age and total body clearance (702.8 ± 499.4 ml/h/kg); however, weak associations between age and the itraconazole distribution volume (r2 = 0.18, P = 0.02), Cmax (r2 = 0.14, P = 0.045), and terminal elimination rate (r2 = 0.26, P < 0.01) were noted. Itraconazole infusion appeared to be well tolerated in this population with a single adverse event (stinging at the site of infusion) deemed to be related to study drug administration. Based on the findings of this investigation, it appears that intravenous itraconazole can be administered to infants beyond 6 months, children, and adolescents using a weight-normalized approach to dosing.

With both traditional and emerging fungal pathogens contributing to an increasing rate of morbidity, invasive mycoses remain a serious and potentially fatal complication for immunocompromised children (1, 16, 23, 26, 27, 31). In recent years, a growing number of new therapeutic agents have found their way to market (28). However, the management of systemic fungal infections is still restricted to a relatively small number of drug classes encompassing a limited number of pharmacologic actions (i.e., most are cell wall-acting agents). As such, the spectrum of activity and established efficacy, in combination with the pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of each agent, will shape their role in therapy.

Itraconazole is a first-generation synthetic triazole antifungal that has been in clinical use for nearly two decades. Although fungistatic against pathogenic yeast, itraconazole retains activity against a portion of fluconazole-resistant isolates and demonstrates fungicidal activity against a number of filamentous organisms that cause severe invasive disease (25). Compared to other members of its class, itraconazole demonstrates a number of favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics, including a protracted half-life, extensive tissue distribution, and an active metabolite whose activity lies within a single twofold dilution of the parent (13, 24). The development of an oral solution which makes use of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) as a solubilizing agent has, in part, remedied the less-than-ideal bioavailability profile of the innovator capsule (7); however, the systemic availability with oral administration remains restricted to less than 60% of the administered dose.

More recently, an intravenous formulation of itraconazole has been licensed for use. The availability of a parenteral product affords the opportunity to bypass significant presystemic clearance and achieve higher concentrations earlier in the course of treatment. It offers a means to administer drug to populations where oral formulations are impractical and also simplifies weight-based administration for pediatric patients. Although existing pediatric pharmacokinetic data are available for the itraconazole oral solution, no data are currently available on the biodisposition of the intravenous formulation in this population. The present study was conducted to characterize the pharmacokinetics of itraconazole, along with its hydroxy-metabolite and the carrier HP-β-CD after single-dose administration of the parenteral product to children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Thirty-three infants, children, and adolescents considered to be at risk for developing a fungal infection were enrolled in this investigation. Subjects were ineligible for enrollment if they met any of the following criteria: (i) clinical and biochemical evidence of abnormal hepatic or renal function; (ii) concomitant administration of known CYP3A substrates, inducers, or inhibitors (or administration of these same agents to a nursing mother of a participant); (iii) known hypersensitivity to itraconazole or any of the excipients in the intravenous formulation; or (iv) exposure to an investigational drug administered as part of a clinical trial within 30 days of study drug administration. In addition, female subjects who had attained menarche were required to have a negative serum pregnancy test prior to administration of the study drug.

A medical history, physical examination, and clinical laboratory tests (complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, liver function tests, and urinalysis) were performed for each subject prior to administration of study drug and again at completion of the study. The study protocol was approved by the Investigational Review Boards of each participating institution, and all subjects were enrolled after obtaining informed parental permission and patient assent when appropriate (i.e., >7 years of age).

Study design.

The study was conducted as an open-label, multicenter, single-dose evaluation of itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD pharmacokinetics in children 6 months through 16 years of age with the goal of enrolling children in four age cohorts (<2 years, 2 to 6 years, 6 to 12 years, and >12 years). Subjects received a single 2.5-mg/kg dose of itraconazole in 0.1-g/kg HP-β-CD administered as a constant-rate intravenous infusion over 1 h. Samples acquired for the purpose of pharmacokinetic determinations were collected from a venous cannula placed in the contralateral extremity. All subjects were required to remain at the participating study facility through the first 24-h postdose sample collection period.

Sample collection.

In children >2 years old, venous blood samples (4 ml) for the determination of itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD were collected from an indwelling venous catheter into sodium heparin-containing tubes. Samples were collected immediately prior to drug administration and at 1, 2, 5, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after the start of intravenous infusion. Due to blood volume limitations, children <2 years old were randomized to pharmacokinetic analyses for the determination of either itraconazole and its hydroxy-metabolite or HP-β-CD. Blood samples (2 ml) were obtained immediately prior to drug administration and at 1, 2, 5, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the start of intravenous infusion for itraconazole and metabolite or at 1, 2, 5, 8, and 12 h after the start of intravenous infusion for HP-β-CD. Plasma was separated by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and stored in polyethylene tubes at −20°C until analyzed.

Urine was collected via spontaneous voluntary voiding, from an indwelling urinary catheter (in children requiring catheterization as part of non-study-related medical care), or from wood pulp-based diapers for the purpose of determining urinary HP-β-CD levels. All urine produced over 24 h on the first day of dosing was collected and pooled at the following intervals: −4 to 0 h (predose) and 0 to 4 h, 4 to 8 h, 8 to 12 h, and 12 to 24 h after the start of study drug administration. Total volume and pH were recorded, and urine aliquots were frozen at −20°C until analysis.

Analytical procedures. (i) Itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole.

Samples were allowed to thaw unassisted at room temperature, and 1 ml was added to a tube containing 100 μl of methanol, 100 μl of internal standard (2 μg/ml; R051012; Janssen, Beerse, Belgium), and 1 ml of 50 mM disodium-tetraborate. Liquid-liquid extraction was performed with 4 ml of isoamylalcohol-heptane (10:90) by placing samples on a tube rotator for 15 min. Samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 4,000 rpm, the aqueous layer was frozen, and the organic layer was transferred to a clean tube. The aqueous layer was extracted again, as described above, and the organic layers were combined. Analytes were back extracted into 2 ml of 2 M HCl for 15 min, the sample was centrifuged, the aqueous layer was frozen, and the organic layer was discarded. A total of 600 μl of 25% ammonia was added to the thawed aqueous layer, and the analytes were back extracted into 2.5 ml of isoamylalcohol-heptane (5:95) reserving the organic phase, repeating the process once as described above, and combining the organic layers. The sample was evaporated to dryness, reconstituted with 150 μl of 10 mM ammonium acetate-acetonitrile (50:50), and transferred to an autosampler.

A 100-μl volume of sample was injected onto the high-pressure liquid chromatography system, and the analytes were separated on a C18 column (3 μm, 100 × 4.6 mm [inner diameter]; Alltech) maintained at room temperature. The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate-acetonitrile-methanol (315:550:135) pumped at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. The eluate was monitored with UV detection (λ-263 nm).

A ten-point standard curve using the peak height ratio of active compound to internal standard was prepared daily and used to calculate all plasma itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole concentrations. The analytical method demonstrated linearity (with 1/y2 weighting) at plasma itraconazole concentrations ranging from 2 to 2,000 ng/ml (r2 > 0.99) and hydroxyitraconazole concentrations ranging from 5 to 5,000 ng/ml (r2 > 0.99). Interday assay variability was consistently <10% for concentrations within the range of linearity. All assays were performed by an independent laboratory (Analytisch Biochemisch Laboratorium BV, Assen, The Netherlands).

(ii) HP-β-CD.

HP-β-CD concentrations were determined by using a previously validated high-pressure liquid chromatography technique involving post-column complexation with phenolphthalein and visible wavelength detection (29). A seven-point standard curve using the peak area of the analyte was used to calculate all plasma and urine HP-β-CD concentrations. The lower limits of quantitation were 5 ng/ml for plasma samples and 25 ng/ml for urine samples. The analytical method demonstrated goodness-of-fit (r2 > 0.99) with log transformation of the data at plasma HP-β-CD concentrations ranging from 5 to 500 ng/ml and urine HP-β-CD concentrations ranging from 25 to 2,500 ng/ml. The interday assay variabilities were <10% for all plasma standards and <12% for all urine standards within their respective ranges. HP-β-CD analyses were performed by Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V. (Beerse, Belgium).

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis.

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analyses were conducted by using WinNonlin Enterprise version 3.3 (Pharsight Corp.) and SPSS (version 11.5; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Plasma concentration-time data were evaluated by using a model independent approach. Individual Cmax and tmax were determined by visual inspection of the plasma concentration-time profile. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h postdose (AUC0-24) was determined by using the trapezoidal rule. Extrapolation of the AUC to infinity (AUC0-∞) was calculated by summation of AUC0-n + Cn/λz, where Cn represents the predicted plasma concentration at the final quantifiable postdose time point, and λz is the apparent terminal elimination rate constant. Total body clearance (CL) and apparent distribution volume (Vz) were calculated from the AUC0-∞. The amount of HP-β-CD excreted unchanged in urine over 24 h (Ae24) was determined by summing the products of urine volumes and urine HP-β-CD concentrations.

In addition to the noncompartmental analysis (NCA), an exploratory population pharmacokinetic analysis was undertaken by using NONMEM (version V, level 1.1; ICON, Ellicott City, MD). Multicompartment pharmacokinetic models with first-order elimination from the central compartment were tested, and the models were parameterized in terms of clearance, volume of distribution, and intercompartmental rates. The final model was used to examine the influence of demographic covariates on the pharmacokinetics of itraconazole and HP-β-CD in this patient population.

Itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD pharmacokinetic parameters were examined by using standard descriptive statistics. Univariate analysis of variance and nonlinear regression techniques were used to evaluate the relationship between demographic variables and pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. The significance limit for all statistical analyses was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Population.

A total of 33 subjects (14 female; 9 African-American, 20 Caucasian, 3 Hispanic, 1 Asian) ranging in age from 7 months to 17 years (8.1 ± 5.2 years) and in weight from 6.5 to 87.8 kg (31.1 ± 22.7 kg) completed this multicenter study. Demographic data for the individual cohorts are provided in Table 1. The majority of participants were receiving broad spectrum antibiotics for infections and/or conditions that included cystic fibrosis with pneumonia (n = 9); malignancy with fever and neutropenia (n = 7); lower respiratory tract infection (n = 5); upper respiratory tract infection (n = 4); postsurgical prophylaxis (n = 2); perforated appendix (n = 2); and meningitis, trauma, urinary tract infection, or enteric infection (n = 1 each).

TABLE 1.

Demographic data grouped by age cohort

| Parametera | Mean demographic data (range) or ratio at age:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mo to 2 yr (n = 6) | >2 to 6 yr (n = 9) | >6 to 12 yr (n = 7) | >12 to 16 yr (n = 11) | |

| Age (yr) | 1.4 (0.7-2.0) | 4.2 (2.2-5.6) | 9.5 (8.0-11.1) | 14.0 (12.3-16.9) |

| Wt (kg) | 9.1 (6.5-11.9) | 18.2 (13.8-25.8) | 28.8 (22.4-48.5) | 55.1 (29.8-87.8) |

| Ht (cm) | 67.8 (29.2-86.5) | 102.2 (84.0-131.0) | 130.4 (120.0-160.0) | 151.1 (135.0-167.0) |

| Sex (F:M) | 2:4 | 3:6 | 4:3 | 5:6 |

| Race (AA:C:H:A) | 2:3:0:1 | 4:4:1:0 | 2:4:1:0 | 1:9:1:0 |

F, female; M, male; AA, African American; C, Caucasian; H, Hispanic; A, Asian.

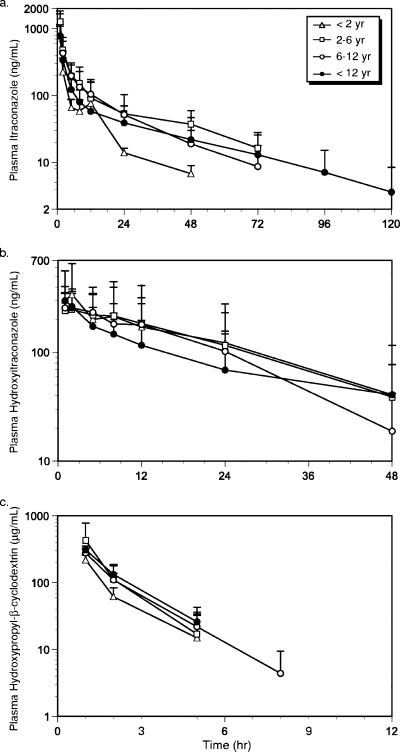

The mean plasma itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD concentration-time data are illustrated in Fig. 1. The pharmacokinetic parameters for each of the analytes are summarized in Table 2. For ease of comparison, the data have been segregated by the age cohorts determined at the time of enrollment. A population pharmacokinetic analysis was also performed using a model-dependent compartmental approach, and the estimated parameters for clearance and volume of distribution were consistent with those reported herein (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Mean plasma concentration-time curves by age group for itraconazole (a), hydroxyitraconazole (b), and HP-β-CD (c). The standard deviations are also indicated.

TABLE 2.

Itraconazole, hydroxyitraconazole, and HP-β-CD pharmacokinetic parameters after a single intravenous infusion of itraconazole (2.5 mg/kg) and HP-β-CD (0.1 g/kg)

| Parametera | Mean value ± SDb at age:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 6 mo to 2 yr (n = 3) | >2 to 6 yr (n = 9) | >6 to 12 yr (n = 7) | >12 to 16 yr (n = 11) | |

| Itraconazole | |||||

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 1,015 ± 692 | 827 ± 859 | 1,553 ± 918 | 785 ± 301 | 806 ± 381* |

| AUC24 (ng·h/ml) | 4,922 ± 6,784 | 2,121 ± 1,231 | 9,510 ± 11,316 | 3,765 ± 1,711 | 2,669 ± 1,076 |

| CL (ml/h/kg) | 702.8 ± 499.4 | 1,143 ± 513 | 529 ± 611 | 621 ± 340 | 777 ± 455 |

| Vz (liters/kg) | 18.5 ± 14.2 | 23.6 ± 15.2 | 8.3 ± 7.1 | 13.9 ± 5.8 | 28.5 ± 15.9 |

| t1/2 (h) | 20.2 ± 12.8 | 13.3 ± 4.15 | 14.0 ± 8.05 | 17.2 ± 7.94 | 29.0 ± 15.6 |

| Hydroxyitraconazole | |||||

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 293 ± 133 | 265 ± 257 | 299 ± 162 | 277 ± 104 | 321 ± 93* |

| tmax (h) | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4* |

| AUC24 (ng·h/ml) | 3,811 ± 2,794 | 4,155 ± 3,657 | 4,249 ± 4,103 | 4,166 ± 2,036 | 3,133 ± 1,789 |

| t1/2 (h) | 13.3 ± 7.0 | 16.6 ± 3.07 | 12.7 ± 7.40 | 14.3 ± 6.76 | 12.3 ± 8.06 |

| HP-β-CD | |||||

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 329 ± 200 | 220 ± 40.1 | 429 ± 348 | 279 ± 50.8 | 304 ± 44* |

| AUC24 (μg·h/ml) | 641.5 ± 265.0 | 857 ± 751 | 643 ± 291 | 606 ± 136 | 609 ± 184 |

| CL (ml/h/kg) | 178 ± 66.9 | 177 ± 184 | 184 ± 80.7 | 173 ± 46.6 | 176 ± 47.6 |

| Vz (liters/kg) | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.34 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.06 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 4.8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Fe (% of dose) | 49 ± 27 | 56 ± 38† | 45 ± 30‡ | 52 ± 23§ | 46 ± 28# |

Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; tmax, time of maximum plasma concentration; AUC24, area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h postdose; CL, total body clearance; Vz, apparent distribution volume; t1/2, half-life; Fe, fraction excreted unchanged in the urine over 24 h.

*, n = 10 owing to an interruption in the infusion of one subject. †, n = 4; ‡, n = 3; §, n = 5; #, n = 8.

Itraconazole.

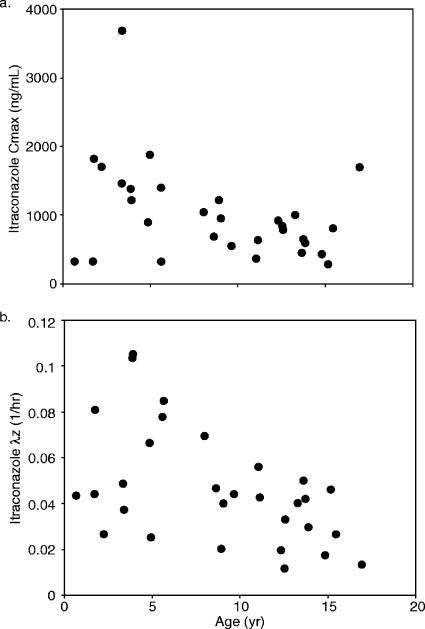

The itraconazole pharmacokinetic parameters were highly variable, with most spanning more than 1 order of magnitude (Table 2). A weak, albeit significant positive association between age and Vz was evident (r2 = 0.18, P = 0.02), along with a corresponding negative relationship for Cmax with age accounting for ca. 15% of the variability observed in this parameter (r2 = 0.14, P = 0.045, Fig. 2a). A modest relationship between age and terminal elimination rate constant for the parent drug was observed (r2 = 0.26, P < 0.01), with λz dropping (i.e., half-life increasing) with increasing age (Fig. 2b). However, essentially no age dependence was observed for plasma clearance and AUC0-24.

FIG. 2.

Scatter plots of age versus itraconazole Cmax (a) and λz (b).

The population pharmacokinetic three-compartment model with first-order elimination well described the plasma concentration profiles of itraconazole in the pediatric patients. Body weight was identified as an important covariate for this population model. Based on the mixed-effect pharmacokinetic analysis of itraconazole, the population estimated values of clearance (CL), volume of distribution of the central compartment 1 (V1), intercompartmental flow rate between central and peripheral compartment 2 (Q2), volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment 2 (V2), intercompartmental flow rate between central and peripheral compartment 3 (Q3), and volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment 3 (V3) were 16.9 liters/h, 63.8 liters, 30.2 liters/h, 134 liters, 9.57 liters/h, and 88.1 liters, respectively, for a 30-kg child. The average body weight for the pediatric subjects 6 to 12 years old was 28.9 kg, and the population analysis was performed by normalizing the effect of body weight based on 30 kg; hence, the parameter estimates from the NCA from this age group was chosen for the comparison of the results between the NCA and the population analysis. The NCA-based estimated CL was 18.6 liters/h (i.e., 0.621 liters/h/kg × 30 kg), which is comparable to the population analysis-based estimate of CL (i.e., 16.9 liters/h).

Hydroxyitraconazole.

In contrast to the parent drug, there was no relationship between age and estimates of exposure (e.g., Cmax and AUC) for the hydroxy-metabolite. Accordingly, an age-associated increase in the Cmax ratio of hydroxyitraconazole to itraconazole would be expected and was observed in this population (r2 = 0.2, P = 0.014). However, this finding had little bearing on the AUC ratio over the 24-h postdose interval which did not change systematically with increasing age.

HC-β-CD.

Although measurable concentrations of metabolite and parent compound were detected through 2 and 3 days, respectively, concentrations of the carrier fell below quantifiable limits by 12 h (Fig. 1). The volume of distribution for HP-β-CD approximated the extracellular fluid spaces and a trend in the relationship between age and HP-β-CD distribution volume was noted with age accounting for nearly 15% of the variability observed in this parameter; however, the relationship was not significant. The total plasma clearance of HP-β-CD approximated estimates of the glomerular filtration rate; however, limited information on renal clearance could be garnered from the data owing to a large number of children with urinary HP-β-CD profiles that were not evaluable (incomplete urine collection [n = 6], calculated CrCl that was not physiologic [n = 4], and quantitative problems [n = 3]). On average, 49% ± 27% of the carrier was eliminated in the urine during the first 24 h. There did not appear to be an association between the amount excreted (Ae24) and calculated creatinine clearance or underlying disease state nor was there a relationship between Ae24 and other demographic variables. No other HP-β-CD pharmacokinetic parameter demonstrated age dependence, and any trends observed in the data, including the apparent increase in half-life in the youngest subjects, were accounted for by individual outliers.

The population pharmacokinetic two-compartment model with first-order elimination well described the plasma concentration profiles of HP-β-CD in the pediatric patients. Body weight was identified as an important covariate for this population model. The population estimated values of clearance (CL), volume of distribution of the central compartment 1 (V1), intercompartmental flow rate between central and peripheral compartment 2 (Q2), and volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment 2 (V2) were 5.27 liters/h, 6.76 liters, 0.85 liter/h, and 2.9 liters, respectively, for a 30-kg child. The estimated CL was similar to that from NCA (5.27 liters/h versus 5.19 liters/h [0.173 liters/h/kg × 30 kg]), respectively.

Tolerability.

Overall, itraconazole appeared to be well tolerated among the study participants with a single individual experiencing stinging at the site of infusion. None of the remaining individuals enrolled in this investigation experienced adverse events that were deemed by the investigator to be related to the study drug. In addition, no clinically significant changes in serum chemistry or hematology parameters were observed for any participant over the course of the study.

DISCUSSION

The influence of development on the biodisposition of parenterally administered itraconazole appears to be limited from infancy beyond 6 months of age through adolescence, as evidenced by the absence of any considerable relationships between age and the pharmacokinetic parameters determined during this investigation. Consequently, the large degree of variability observed in this investigation likely reflects the wide degree of interindividual variation reported for the activity of the quantitatively important proteins involved in the biodisposition of itraconazole (e.g., CYP3A4) (15).

Compared to existing pharmacokinetic data obtained in children, estimates of itraconazole exposure were higher per weight-normalized dose (in mg/kg) after intravenous compared to oral administration (14, 18). Not surprisingly, the AUC ratio of metabolite to parent compound was lower after intravenous administration. However, this finding was only evident in children over the age of 2 years with the ratio in children under the age of two comparable between formulations (14, 18). This finding may reflect a disproportionate reduction in the bioavailability of the metabolite and parent compound (independent of biotransformation) in young infants; however, it may also reflect a reduced capacity for itraconazole metabolism at the level of the intestine in these children. This is consistent with the finding of Johnson et al., who reported reduced 6β-OH-testosterone formation (catalyzed principally by CYP3A4) in the duodenal biopsies of neonates and young infants compared to older children and adolescents (21) and is supported by the putative contribution of intestinal CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent CYP1A1, in the formation of hydroxyitraconazole (22).

Despite the large degree of variability in itraconazole pharmacokinetics observed in the pediatric population, all of the children in the present study demonstrated peak itraconazole plasma levels that fell within the range of reported MIC90 values (0.12 to 2 μg/ml) of the majority of susceptible yeast and filamentous pathogens. At the dose used, none of the children sustained plasma itraconazole concentrations above the traditional “target” trough concentrations (i.e., 250 ng/ml) at 12 h (17); however, the clinical relevance of this observation remains unclear given that the estimates of systemic exposure described herein represent observations after a single dose and do not reflect the magnitude of accumulation expected after multiple dosing. Owing to the complex pharmacokinetic behavior observed for itraconazole after oral administration (e.g., disproportionate increase in exposure with increasing dose, an increase in half-life with increased duration of therapy) (6, 19), we elected not to conduct steady-state simulations since their representative accuracy could not be ensured.

In addition to target trough concentrations, a number of investigations using a murine candidiasis model demonstrated a strong relationship between the ratios of free drug exposure to MIC (AUCfree/MIC) and log10 reduction in CFU (2-4). In each investigation, the 50% effective concentration was achieved with doses that result in AUCfree/MIC ratios of 20 with a range from 6 to 60 depending on the agent and fungal isolate. While the exposures resulting from a single 2.5-mg/kg intravenous dose of itraconazole in our population achieved an AUCtotal/MIC ratio that would satisfy these criteria, we would predict the ratios to fall short of 50% effective concentration values when corrected for protein binding. However, free drug concentrations were not determined in this investigation. As such, these findings are difficult to interpret in the context of human infection given the single-dose nature of the present study and the fact that antifungal response is contingent upon a number of nonpharmacokinetic variables, including the pathogen, the infection site, and the immune status of the host (5, 9, 11, 12).

Although we observed satisfactory tolerability in this investigation, a true assessment of safety in children will require evaluation with multiple dosing. Notwithstanding, we would not expect the adverse event rate in children to vary substantially from existing reports of this formulation in older populations. As described previously, the modified cyclodextrins (e.g., HP-β-CD) offer a substantially improved safety profile over their unmodified parent cyclodextrins (20). Hydroxyalkylether substitution mitigates the nephrotoxicity observed with the unmodified and methylated cyclodextrins such that only limited, reversible nephrotoxicity has been observed in animal models with doses 5 to 10 times higher than were used in the present study (20). Furthermore, the average peak plasma concentrations of HP-β-CD observed in this investigation were comparable to or lower than those observed in adults after a fixed 200-mg parenteral itraconazole dose, and they fell more than 1 order of magnitude below the concentrations required to cause appreciable hemolysis in vitro (8, 20).

In conclusion, a single intravenous dose of itraconazole appears to be well tolerated in pediatric patients and affords the ability to rapidly achieve therapeutic concentrations of itraconazole in plasma. The large degree of variability in itraconazole pharmacokinetics in our study cohort precluded any consistent demonstration of age dependence in the disposition of the drug. This is in contrast to other azole antifungals, which appear to demonstrate a role for ontogeny in their biodisposition (10, 30). Consequently, it would appear that weight-based doses of intravenous itraconazole can be administered without regard for age in young children and adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, L.L.C., Raritan, NJ, and grants 5U10HD031323-13, 5U10HD031313-14, 5U10HD031324-13, and 5U10HD031318-13 (Network of Pediatric Pharmacology Research Units) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abelson, J. A., T. Moore, D. Bruckner, J. Deville, and K. Nielsen. 2005. Frequency of fungemia in hospitalized pediatric inpatients over 11 years at a tertiary care institution. Pediatrics 116:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andes, D., K. Marchillo R. Conklin, G. Krishna, F. Ezzet, A. Cacciapuoti, and D. Loebenberg. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, posaconazole, in a murine model of disseminated candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:137-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andes, D., K. Marchillo, T. Stamstad, and R. Conklin. 2003. In vivo pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, ravuconazole, in a murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1193-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andes, D., K. Marchillo, T. Stamstad, and R. Conklin. 2003. In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, voriconazole, in a murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3165-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andes, D., and M. van Ogtrop. 1999. Characterization and quantitation of the pharmacodynamics of fluconazole in a neutropenic murine disseminated candidiasis infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2116-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barone, J. A., J. G. Koh, R. H. Bierman, J. L. Colaizzi, K. A. Swanson, M. C. Gaffar, B. L. Moskovitz, W. Mechlinski, and V. Van de Velde. 1993. Food interaction and steady-state pharmacokinetics of itraconazole capsules in healthy male volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:778-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barone, J. A., B. L. Moskovitz, J. Guarnieri, A. E. Hassell, J. L. Colaizzi, R. H. Bierman, and L. Jessen. 1998. Enhanced bioavailability of itraconazole in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin solution versus capsules in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1862-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boogaerts, M. A., J. Maertens, R. Van Der Geest, A. Bosly, J. L. Michaux, A. Van Hoof, M. Cleeren, R. Wostenborghs, and K. De Beule. Pharmacokinetics and safety of a 7-day administration of intravenous itraconazole followed by a 14-day administration of itraconazole oral solution in patients with hematologic malignancy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:981-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bow, E. J., M. Laverdiere, N. Lussier, C. Rotstein, M. S. Cheang, and S. Ioannou. 2002. Antifungal prophylaxis for severely neutropenic chemotherapy recipients: a meta analysis of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Cancer 94:3230-3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brammer, K. W., and P. E. Coates. 1994. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in pediatric patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess, D. S., and R. W. Hastings. 2000. A comparison of dynamic characteristics of fluconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B against Cryptococcus neoformans using time-kill methodology. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess, D. S., R. W. Hastings, K. K. Summers, T. C. Hardin, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2000. Pharmacodynamics of fluconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B against Candida albicans. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conte, J. E., Jr., J. A. Golden, J. Kipps, M. McIver, and E. Zurlinden. 2004. Intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of itraconazole and 14-hydroxyitraconazole at steady state. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3823-3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Repentigny, L., J. Ratelle, J. M. Leclerc, G. Cornu, E. M. Sokal, P. Jacqmin, and K. de Beule. 1998. Repeated-dose pharmacokinetics of an oral solution of itraconazole in infants and children. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 42:404-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducharme, M. P., R. L. Slaughter, L. H. Warbasse, P. H. Chandrasekar, V. Van de Velde, G. Mannens, and D. J. Edwards. 1995. Itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole serum concentrations are reduced more than tenfold by phenytoin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 58:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dvorak, C. C., W. J. Steinbach, J. M. Brown, and R. Agarwal. 2005. Risks and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 36:621-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groll, A. H., S. C. Piscitelli, and T. J. Walsh. 2001. Antifungal pharmacodynamics: concentration-effect relationships in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacotherapy 21:133S-148S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groll, A. H., L. Wood, M. Roden, D. Mickiene, C. C. Chiou, E. Townley, L. Dad, S. C. Piscitelli, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of cyclodextrin itraconazole in pediatric patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 46:2554-2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardin, T. C., J. R. Graybill, R. Fetchick, R. Woestenborghs, M. G. Rinaldi, and J. G. Kuhn. 1988. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole following oral administration to normal volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1310-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irie, T., and K. Uekama. 1997. Pharmaceutical applications of cyclodextrins. III. Toxicological issues and safety evaluation. J. Pharm. Sci. 86:147-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, T. N., M. S. Tanner, C. J. Taylor, and G. T. Tucker. 2001. Enterocytic CYP3A4 in a paediatric population: developmental changes and the effect of coeliac disease and cystic fibrosis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 51:451-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isoherranen, N., K. L. Kunze, K. E. Allen, W. L. Nelson, and K. E. Thummel. 2004. Role of itraconazole metabolites in CYP3A4 inhibition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 32:1121-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nucci, M., and K. A. Marr. 2005. Emerging fungal diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odds, F. C., and H. Vanden Bossche. 2000. Antifungal activity of itraconazole compared with hydroxy-itraconazole in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:371-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaller, M. A., L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, S. A. Messer, S. Tendolkar, and D. J. Diekema. 2005. In vitro susceptibilities of clinical isolates of Candida species, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus species to itraconazole: global survey of 9,359 isolates tested by clinical and laboratory standards institute broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3807-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen, G. P., K. Nielsen, S. Glenn, J. Abelson, J. Deville, and T. B. Moore. 2005. Invasive fungal infections in pediatric oncology patients: 11-year experience at a single institution. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 27:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smolinski, K. N., S. S. Shah, P. J. Honig, and A. C. Yan. 2005. Neonatal cutaneous fungal infections. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 17:486-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinbach, W. J. 2005. Antifungal agents in children. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 52:895-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szathmary, S. C. 1989. Determination of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in plasma and urine by size-exclusion chromatography with post-column complexation. J. Chromatogr. 487:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh, T. J., M. O. Karlsson, T. Driscoll, A. G. Arguedas, P. Adamson, X. Saez-Llorens, A. J. Vora, A. C. Arrieta, J. Blumer, I. Lutsar, P. Milligan, and N. Wood. 2004. Pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous voriconazole in children after single- or multiple-dose administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2166-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wingard, J. R. 2005. The changing face of invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 17:89-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]