Abstract

Paenibacillus polymyxa (formerly Bacillus polymyxa) PKB1 has been identified as a potential agent for biocontrol of blackleg disease of canola, caused by the pathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. The factors presumed to contribute to disease suppression by strain PKB1 include the production of fusaricidin-type antifungal metabolites that appear around the onset of bacterial sporulation. The fusaricidins are a family of lipopeptide antibiotics consisting of a β-hydroxy fatty acid linked to a cyclic hexapeptide. Using a reverse genetic approach based on conserved motifs of nonribosomal peptide synthetases, a DNA fragment that appears to encode the first two modules of the putative fusaricidin synthetase (fusA) was isolated from PKB1. To confirm the involvement of fusA in production of fusaricidins, a modified PCR targeting mutagenesis protocol was developed to create a fusA mutation in PKB1. A DNA fragment internal to fusA was replaced by a gene disruption cassette containing two antibiotic resistance genes for independent selection of apramycin resistance in Escherichia coli and chloramphenicol resistance in P. polymyxa. Inclusion of an oriT site in the disruption cassette allowed efficient transfer of the inactivated fusA allele to P. polymyxa by intergeneric conjugation. Targeted disruption of fusA led to the complete loss of antifungal activity against L. maculans, suggesting that fusA plays an essential role in the nonribosomal synthesis of fusaricidins.

Canola is an economically important oilseed crop grown in Canada and throughout the world. Significant losses in canola seed quality and yield occur every year due to phoma stem canker (blackleg) disease, caused by the fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. The methods that have been applied to control the severity and spread of blackleg include implementation of improved cultural practices, use of fungicides, and breeding of blackleg-resistant cultivars (37), but better control methods are still needed. In an effort to develop efficient and environmentally safe biocontrol agents for blackleg disease, a strain of Paenibacillus polymyxa (designated PKB1) highly inhibitory to the growth of L. maculans was isolated from canola stubble (18).

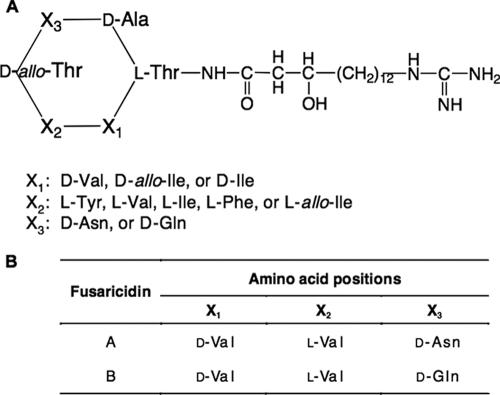

A naturally soilborne bacterium, P. polymyxa possesses several properties desirable in a biocontrol agent active against plant-pathogenic fungi, including production of desiccation- and heat-resistant endospores, and intrinsic resistance to several fungicides and herbicides approved for use on canola crops in Canada. Strains of P. polymyxa have also been shown to produce a wide range of peptide antibiotics, which may give them a growth advantage in the competitive soil environment. The peptide metabolites that have been identified in various isolates of P. polymyxa are generally classified into two groups according to their antimicrobial activities. Members of the first group include the polymyxins (17), polypeptins (32), jolipeptin (12, 13), gavaserin, and saltavalin (27) and are typified by antibacterial activity against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and by inclusion of 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (DAB) as a nonproteinogenic amino acid. The second group consists of a single family of closely related peptides variously designated gatavalin (24), fusaricidins A to D (15, 16), or LI-F antibiotics (12 distinct compounds) (20, 21), all of which contain an unusual fatty acid side chain, 15-guanidino-3-hydroxypentadecanoic acid. Their antagonist activity against fungi and gram-positive bacteria and the fact that they have no effect on gram-negative bacteria distinguish this second group of peptides from the first group. All peptides of this second group are referred to as fusaricidins in this paper. The general peptide sequence of the fusaricidins was determined to be l-Thr-X1-X2-d-allo-Thr-X3-d-Ala (Fig. 1A). The β-hydroxy fatty acid is attached to the N-terminal l-Thr via an amide linkage, and the peptide is cyclized by an ester bond between the C-terminal d-Ala and the β-OH group of the N-terminal l-Thr. The antimicrobial activity of the fusaricidins has been shown to vary depending on the amino acids present at three variable positions in the peptide moiety (15, 16, 20, 21), and previous studies (1) revealed that the antifungal activity of PKB1 against L. maculans was mainly attributable to production of a mixture of fusaricidins A and B (Fig. 1B). Although purification methods and primary structures of fusaricidins have been described, the biosynthetic details for these cyclic depsipeptides are still unknown. On the basis of their structural similarity to several lipopeptides isolated from Bacillus strains (i.e., surfactin and lichenysin), we hypothesized that the peptide moiety of the fusaricidins is synthesized through large multienzyme complexes known as nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs).

FIG. 1.

(A) Primary structure of the fusaricidin-type lipopeptide antibiotics from P. polymyxa. (B) Amino acid substitutions at three variable positions in fusaricidins A and B, the analogs associated with the antifungal activity of PKB1 against L. maculans.

NRPSs have modular structures in which each module is responsible for the recognition and incorporation of one amino acid into the final peptide product (23). Generally, the number and order of modules within an NRPS directly corresponds to the primary sequence of the resulting peptide. Modules can be further subdivided into different domains that catalyze the individual reaction steps. Three types of domains, the adenylation (A), thiolation (T), and condensation (C) domains, are essential for nonribosomal peptide synthesis. The A domains activate the corresponding amino acids as aminoacyl adenylates, which are subsequently transferred to 4′-phosphopanthetheinyl cofactors attached to downstream T domains. During the stepwise elongation of the peptide chain, formation of the peptide bond between two adjacent aminoacyl intermediates bound to T domains is carried out by the intervening C domain. In some cases, there is an additional epimerization (E) domain in the module, which catalyzes the racemization of the activated l amino acid into its d enantiomer.

To understand the detailed biosynthetic steps involved in production of fusaricidins, cloning and characterization of the fusaricidin biosynthetic gene cluster were a necessary first step. However, this was made difficult by the potential presence of NRPS gene clusters for the other peptides produced by P. polymyxa (1) and by the relative lack of genetic tools available for use in P. polymyxa. In this report, we describe the adaptation to P. polymyxa of a PCR-mediated mutagenesis protocol that has allowed us to identify a putative peptide synthetase gene, fusA, involved in production of fusaricidins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. polymyxa PKB1 (= ATCC 202127) and L. maculans were obtained from P. Kharbanda, Alberta Research Council (Vegreville, Canada). Escherichia coli DH5α was used for subcloning experiments and preparation of plasmids. Luria-Bertani medium was used for E. coli cultures. P. polymyxa was cultivated in glucose broth (GB) (31) at 37°C for fast vegetative growth, while production of fusaricidins was monitored during growth at 28°C in PDB-soy medium consisting of equal volumes of potato dextrose broth (PDB) (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and soy medium (29). Potato dextrose agar (PDA) was used for growth of L. maculans and for fusaricidin bioassays. Brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (BD Biosciences) was used for conjugation experiments and for the preparation of P. polymyxa genomic DNA. When required, antibiotics were added to growth media at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; apramycin, 50 μg/ml for E. coli and 25 μg/ml for P. polymyxa; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml for E. coli and 5 μg/ml for P. polymyxa; and polymyxin B, 25 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| L. maculans | Indicator organism for bioassay of fusaricidins | 18 |

| P. polymyxa strains | ||

| PKB1 | Wild-type producer of fusaricidins | 18 |

| A1/A5 | fusA mutants (single crossover), Aprar Cmr Kanr | This study |

| A4/A6 | fusA mutants (double crossover), Aprar Cmr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| BW25113 | ΔaraBAD ΔrhaBAD | 3 |

| ET12567 | dam13::Tn9 dcm6 hsdM hsdR Tetr Cmr | 22 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T | E. coli vector for cloning PCR products, Ampr | Promega |

| pBluescript SK(+) | E. coli phagemid, Ampr | Stratagene |

| SuperCos-1 | Cosmid vector for PKB1 genomic library preparation, dual cos sites, Ampr Kanr | Stratagene |

| Col-19 | SuperCos-1-derived cosmid carrying fusA | This study |

| pC194 | Staphylococcus plasmid vector, Cmr | 11 |

| pIJ790 | λ RED (gam bet exo) araC rep101(Ts) Cmr | 8 |

| pIJ773 | aac(3)IV (Aprar) oriTRK2 | 8 |

| pIJ2925 | E. coli cloning vector, Ampr | 14 |

| pIJ9 | pIJ2925 carrying the Aprar CmroriT gene disruption cassette | This study |

| pUZ8002 | tra RP4 Kanr | 25 |

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Aprar, apramycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance.

Plasmids.

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. pUZ8002 (25) is a nontransmissible E. coli plasmid with the ability to mobilize SuperCos-1-derived cosmids into P. polymyxa. pIJ790 (8) carries a temperature-sensitive origin of replication for growth in E. coli and, when induced by arabinose, expresses λ RED recombination functions. pC194 is a Staphylococcus plasmid vector (11) that replicates in P. polymyxa and imparts chloramphenicol resistance and was obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Ohio State University, Columbus).

DNA manipulations.

Routine DNA manipulations were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (30). Chromosomal DNA from P. polymyxa was prepared by a lysozyme-sodium dodecyl sulfate-phenol extraction method (procedure 4 of Hopwood et al. [10]) modified as follows: BHI medium-grown cells were washed twice with 10.3% sucrose, suspended in a lysozyme solution containing 100 μg/ml RNase, and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. After addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate and proteinase K to final concentrations of 2% and 0.2 mg/ml, respectively, the cell lysate was incubated for 15 min at 37°C, followed by repeated extraction with equal volumes of phenol-chloroform (1:1).

The SuperCos-1 genomic library of PKB1 was constructed by partial Sau3AI digestion of genomic DNA, dephosphorylation with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase, and ligation into the BamHI site of the cosmid vector. The resulting ligation mixture was packaged in vitro with Gigapack III Gold (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and transfected into E. coli XL1-Blue MR. Southern blotting onto Hybond N nylon membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech UK, Buckinghamshire, England) and colony lift hybridization were conducted by following the manufacturer's protocol. In hybridization experiments, double-stranded DNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by nick translation (30).

PCR amplification of peptide synthetase genes.

In order to identify putative fusaricidin synthetase genes, a PCR-based approach was used with oligonucleotide primers designed to recognize conserved sequences common to all peptide synthetases (36). Two degenerate oligonucleotides, B1 (5′-CCG GCC GCT GCG GIT G[CT][AT] [CG]IA C-3′) recognizing core motif A2 and J6 (5′-ATG AGA ATT CTA GAG CTC IGA [AG]TG ICC ICC [AC]AG-3′) recognizing core motif T, were used in PCRs with PKB1 genomic DNA as the template to amplify presumptive fragments from peptide synthetase genes. PCR products were directly cloned into pGEM-T for sequencing. The predicted amino acid sequence encoded by one of the PCR-amplified DNA fragments, B1J6-17, showed high similarity to threonine-activating modules of peptide synthetases and thus was chosen as a probe to screen the SuperCos-1 genomic library of PKB1.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA sequence analyses were performed either by the Molecular Biology Facility at University of Alberta or by SeqWright DNA Technology Services (Houston, TX). The nucleotide sequence data were compiled and analyzed using GeneTools 2.0 (BioTools Inc., Edmonton, Canada). The online programs BLAST and ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) were used for homology searches and prediction of open reading frames (ORFs).

PCR-targeted gene disruption. (i) Creation of an Aprar Cmr oriT disruption cassette.

fusA mutants were prepared by modifying the recently described Redirect PCR targeting system (8) to make it appropriate for P. polymyxa. None of the antibiotic resistance cassettes included as part of the Redirect system (Plant Biosciences, Norwich, United Kingdom) were suitable for use with P. polymyxa directly, so the Aprar oriTRK2 cassette from pIJ773 was cloned into pIJ2925 as an EcoRI-HindIII fragment and then modified by insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance gene (cat). The cat gene was removed from pC194 as a Sau3A-HpaII fragment and inserted into a unique NaeI site located between the oriT and aac(3)IV (Aprar) genes, after passage through pIJ2925 and pBluescript SK(+) to pick up appropriate restriction sites, resulting in plasmid pJL9. The new hybrid resistance cassette imparted both apramycin resistance for selection in E. coli and chloramphenicol resistance for selection in P. polymyxa.

(ii) PCR-targeted mutation of fusA.

Primers JRL15-RD (5′-CCT GAT GGC AAT ATT GAA TAT TTG GGG CGG ATC GAC CAT ATT CCG GGG ATC CGT CGA CC-3′) and JRL16-RD (5′-TTT GAC TAG ACG GAC CAC GTT CCG GTG TTC AAC CAT AAC TGT AGG CTG GAG CTG CTT C-3′) were used to amplify the Aprar Cmr oriT disruption cassette using a gel-purified 2.5-kb BglII fragment from pJL9 as the template (Fig. 2A). Each primer consists of a 39-nucleotide (nt) targeting sequence at the 5′ end (not underlined), identical to regions flanking the fusA gene fragment to be deleted, and a 19- or 20-nt priming sequence at the 3′ end (underlined), identical to the disruption cassette. Amplification was conducted under the following PCR conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 2 min; 15 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 2 min with the extension time increased by 2 s per cycle; and a final elongation step of 68°C for 5 min. The amplified DNA fragment was introduced by electroporation into E. coli BW25113 carrying both pIJ790 and the fusA-bearing cosmid Col-19, in which the λ RED functions encoded by pIJ790 promoted homologous recombination between fusA and the PCR-amplified disruption cassette (Fig. 2A and B).

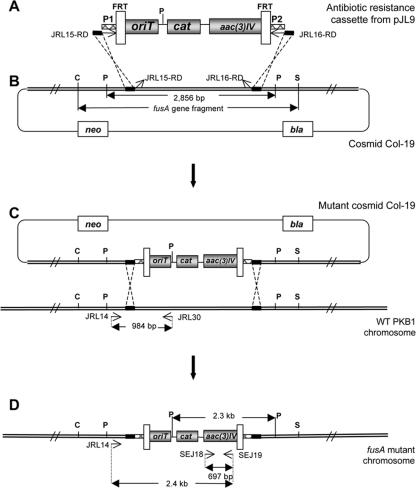

FIG. 2.

PCR-targeted mutagenesis of fusA in P. polymyxa PKB1. Open arrows show the locations and orientations of PCR primers. Abbreviations: C, ClaI; P, PstI; S, SphI. The diagrams are not drawn to scale. (A) The gene disruption cassette containing acc3(IV) (Aprar), cat (Cmr), oriTRK2, and two FRT sequences was amplified from pJL9 with PCR primers JRL15-RD and JRL16-RD. Each primer includes a 39-nt extension sequence at the 5′ end (short thick solid line) identical to the target DNA fragment and a 19- or 20-nt priming sequence at the 3′ end (P1 or P2) identical to the disruption cassette. (B) A region internal to fusA, contained within a 2,856-bp PstI fragment, was targeted for gene replacement by the disruption cassette. The PCR-amplified disruption cassette was transformed into E. coli BW25113/pIJ790 carrying cosmid Col-19, in which the λ RED functions promoted exchange of the region internal to fusA for the disruption cassette. PKB1 DNA is indicated by double lines. (C) The mutant cosmid (conferring Aprar, Ampr, and Kanr) carrying the inactivated fusA allele was mobilized into PKB1 via intergeneric conjugation where exchange with the wild-type allele occurred. (D) Cmr P. polymyxa exconjugants were selected, and successful integration of the disruption cassette in the chromosome was confirmed by colony PCR and Southern hybridization.

(iii) Transfer of mutated fusA to P. polymyxa by intergeneric conjugation.

The resulting mutagenized Col-19 cosmid, in which a 2,394-bp fragment internal to fusA was replaced by the disruption cassette, was then transformed into E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 and from there introduced into the wild-type P. polymyxa PKB1 strain via intergeneric conjugation. Both the donor and recipient strains were prepared for conjugation by growth overnight at 37°C in BHI broth (supplemented with antibiotics as appropriate). Donor and recipient cells were washed three times with equal volumes of fresh BHI medium and then mated (donor/recipient ratio, 5:1) on 0.22-μm Millipore filters placed on BHI medium plates. Following overnight incubation at 28°C, cells from each filter were suspended in 2 ml of BHI broth, and 200-μl aliquots were spread onto GB agar plates containing chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) to select for P. polymyxa exconjugants and polymyxin B (25 μg/ml) to counterselect against the E. coli donor strain. Chloramphenicol-resistant P. polymyxa exconjugants appeared after 24 h of incubation at 37°C.

Colony PCR.

For preliminary identification of P. polymyxa mutants, cells harvested from 100 μl of an overnight GB culture were washed once with 100 μl of a 10.3% sucrose solution, resuspended in 25 μl of distilled water, and heated at 95°C for 15 min. Following centrifugation at 7,000 rpm (Eppendorf microcentrifuge) for 5 min, 5 μl of supernatant was used as a template in a 50-μl PCR mixture. PCRs were performed with either a pair of aac(3)IV-specific primers, SEJ18 (5′-CCG GCG GTG TGC TGC TGG TC-3′) and SEJ19 (5′-CGG CAT CGC ATT CTT CGC ATC C-3′), to test for the presence of a 697-nt fragment internal to the disruption cassette (Aprar Cmr oriT) or the aac(3)IV-specific primer SEJ19 together with a primer flanking the deleted fusA locus, JRL14 (5′-TCG GCC GGA TTT GAC GTC TGA GAA-3′), to verify the correct integration of the disruption cassette (Fig. 2D). A third reaction was performed using JRL14 and a fusA-specific primer, JRL30 (5′-TCC GTC TCC TCC ACC AAA GCC TCT G-3′), in order to distinguish between fusA mutants resulting from single and double crossovers (Fig. 2C).

Antifungal activity bioassay.

Production of fusaricidins was detected by a bioassay with L. maculans as the indicator organism (1). PDA plates were spread with a glycerol stock of L. maculans pycnidiospores, and sample wells were punched out of the agar with a sterile cork borer. For small-scale extraction of fusaricidins, P. polymyxa was grown in PDB-soy medium at 28°C for 72 h. Culture samples (1.5 ml) were harvested by centrifugation, and cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of methanol. Following incubation at 21°C for 30 min, cell suspensions were centrifuged and the fusaricidin-containing supernatants were applied to wells of the bioassay plate. Alternatively, 750-μl portions of whole cultures or culture supernatants were mixed with equal volumes of methanol and supplemented with 10 μl of 1:10-diluted glacial acetic acid. After 30 min of incubation at 21°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation, and 500 μl of each supernatant was air dried to 100 μl. The concentrated extracts were then applied to wells of the bioassay plate. Bioassay plates were incubated overnight at 21°C exposed to room light and then at 28°C in the dark for an additional 72 h.

Extraction of fusaricidin for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

Forty-eight-hour cultures of fusA mutant strain A4 or wild-type strain PKB1, grown on PDB-soy medium, were mixed with an equal volume of methanol and then supplemented with KCl at a concentration of 5% (wt/vol). After 30 min of incubation at 21°C, each cell suspension was harvested by centrifugation, and 25 ml of the supernatant was applied to a SepPak C18 cartridge (Waters) that had been prewetted with 5 ml of methanol and rinsed with 5 ml of water. The loaded cartridge was then eluted with 5 ml of water, 5 ml of 40% methanol, and finally 5 ml of 80% methanol. The 80% methanol extracts were concentrated to dryness under a stream of air and dissolved in 1.0 ml of 50% methanol for analysis.

HPLC analysis.

Samples (0.05 ml) of each 80% methanol concentrate were analyzed by C18 reversed-phase chromatography on a Bondclone 10μ C18 column (8 by 100 mm; Phenomenex) at a flow rate of 2.0 ml/min using a 15-min linear gradient ranging from 30% methanol to 90% methanol, both in 0.1% formic acid, with detection at 220 nm. Fractions (0.5 ml) were collected across the gradient, dried, and bioassayed against L. maculans.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence (7,833 bp) of the fusA fragment from P. polymyxa PKB1 has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. EF451155.

RESULTS

Identification of a putative fusaricidin synthetase gene, fusA.

To clone fusaricidin biosynthetic genes, we designed degenerate oligonucleotide primers corresponding to two conserved core motifs, A2 and T, found in all peptide synthetases. P. polymyxa PKB1 genomic DNA was used as the template for PCR amplification of putative peptide synthetase gene fragments. PCR products of the expected size, approximately 1.65 kb, were obtained, and all 15 different PCR-amplified fragments that were analyzed gave DNA sequence information indicating that they were derived from peptide synthetase genes. Seven of the fragments gave sufficient sequence information to allow analysis of the internal core motifs, A3 to A10, in their deduced amino acid sequences. According to the selectivity-conferring codes identified in the A domains of NRPSs (33), substrate specificities of the A domains derived from these seven PCR-amplified fragments were predicted (Table 2). DNA fragments B1J6-2, B1J6-3, B1J6-5, B1J6-14, and B1J6-19 apparently encode peptide synthetase modules that specifically recognize glutamic acid (Glu) or ornithine (Orn). Neither of these amino acids is found in fusaricidins, suggesting that the fragments were derived from peptide synthetase gene clusters for other peptides. The deduced amino acid sequences of the other two PCR-amplified fragments, B1J6-7 and B1J6-17, displayed high levels of similarity to A domains activating threonine (Thr). Since all fusaricidin analogs have invariant threonine (or allo-threonine) residues at the first and fourth positions of the peptide moiety (Fig. 1A), we chose B1J6-17 as the probe for subsequent screening of a PKB1 genomic DNA library. B1J6-17 exhibits about 80% identity to the Thr-activating module of fengycin synthetase from Bacillus subtilis (34).

TABLE 2.

Predicted substrate specificities of PCR-amplified peptide synthetase gene fragments and the fusA fragment, based on the selectivity-conferring codes of NRPSs

| A domaina | Amino acid residues involved in substrate recognition at position:

|

Predicted substrate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 235 | 236 | 239 | 278 | 299 | 301 | 322 | 330 | 331 | ||

| B1J6-2 | D | A | W | I | F | G | G | M | P | Glu |

| B1J6-3 | D | A | W | I | F | G | A | I | T | Glu |

| B1J6-5 | D | V | C | E | T | G | T | I | E | Orn |

| B1J6-7 | D | F | W | N | —b | G | M | — | — | Thr |

| B1J6-14 | D | V | G | E | I | G | A | P | — | Orn |

| B1J6-17 | D | F | W | N | I | G | M | V | H | Thr |

| B1J6-19 | D | V | G | E | I | G | S | I | D | Orn |

| FusA-A1 | D | F | W | N | I | G | M | V | H | Thr |

| FusA-A2 | D | A | F | W | L | G | C | T | F | Val |

FusA-A1, first A domain of the fusA-encoded amino acid sequence (FusA); FusA-A2, second A domain of FusA.

—, gaps in DNA sequence prevented identification of the corresponding amino acid.

Six cosmids hybridizing to the B1J6-17 probe were obtained by screening a 2,000-clone SuperCos-1 genomic library of PKB1. By using restriction analysis and Southern hybridization, the six cosmids could be divided into two main groups. Five cosmids with overlapping DNA inserts comprised group 1, whereas the single cosmid making up group 2 apparently contained genes from a separate locus on the chromosome, indicating that two distinct peptide synthetase gene clusters were identified in the PKB1 strain. We selected one cosmid from group 1, designated Col-8 (∼39-kb insert), and the single cosmid from group 2, designated Col-19 (∼36.4-kb insert), for further study. By analyzing the deduced amino acid sequence from a subcloned PstI fragment of Col-8 that hybridized with the B1J6-17 probe, we identified a putative Thr-activating NRPS module flanked by two putative Orn-activating modules (data not shown). This amino acid sequence (Orn-Thr-Orn) is inconsistent with the structure of fusaricidins, suggesting that the peptide synthetase genes in Col-8 are unlikely to be part of the fusaricidin biosynthetic gene cluster.

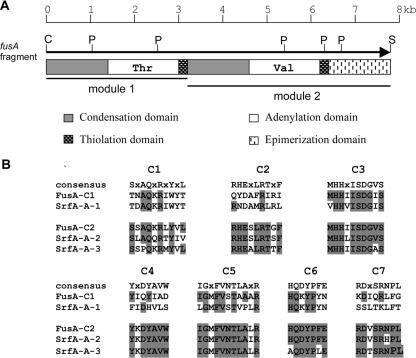

In contrast, analysis of a 7.8-kb ClaI-SphI fragment subcloned from Col-19, which hybridized to the B1J6-17 probe, revealed the presence of an incomplete 7,692-bp ORF encoding a peptide synthetase with modules consistent with those expected for biosynthesis of fusaricidins. This partial ORF (designated fusA) starts with an ATG codon at nt 141 and is preceded by a putative ribosome-binding site (AGGAGT) located 7 bp upstream. Within the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by fusA (designated FusA), two modules typical of peptide synthetases were identified. As shown in Fig. 3A, a total of seven catalytic domains can be distinguished: three in the first module and four in the second. By comparison with the specificity codes for other peptide synthetases, the amino acid substrates most likely to be recognized by these two modules are threonine and valine (Val), respectively (Table 2). The N-terminal C domain in the first module exhibited 57% similarity to the first C domain of SrfA-A (2, 7), which is believed to act as an acceptor for the fatty acid moiety of the lipopeptide, surfactin (26). In addition, the presence of an E domain at the C-terminal end of the second module indicated that the activated amino acid is likely to be converted into the d configuration. Taken together, these findings suggest that fusA encodes a peptide synthetase consisting of at least two modules, incorporating l-Thr in the first position and d-Val in the second position of the peptide product, and that the l-Thr residue is associated with a lipid moiety. All of these features are in agreement with the primary structure of the fusaricidins (Fig. 1A), but given the large number of peptide metabolites known to be produced by P. polymyxa and the possibility of other as-yet-undescribed peptides, independent confirmation of the involvement of fusA in production of fusaricidins was required.

FIG. 3.

(A) Domain organization of the peptide synthetase derived from the fusA fragment carried on cosmid Col-19. Abbreviations: C, ClaI; P, PstI; S, SphI. (B) Comparison of the conserved core motifs within the C domains of FusA with those of SrfA-A from B. subtilis. Shading indicates sequence identity with the consensus sequence. The C domains in each peptide synthetase are numbered according to their order in the protein.

Adaptation of PCR-targeted mutagenesis for P. polymyxa.

The Redirect PCR targeting protocol from Plant Bioscience (Norwich, United Kingdom) was originally developed for use with Streptomyces (8). Therefore, modifications were required before the same technology could be applied to P. polymyxa. In order to disrupt fusA carried on cosmid Col-19 and transfer the mutation to P. polymyxa PKB1, a series of gene replacement cassettes supplied with the Redirect PCR targeting materials was tested for suitability of the antibiotic resistance genes for use in P. polymyxa. At the same time, we also tested the susceptibility of PKB1 to various antibiotics at concentrations commonly used to inhibit Bacillus spp. Initially, the aac(3)IV gene carried in the Aprar oriT disruption cassette (from pIJ773) appeared to be a useful antibiotic marker that conferred apramycin resistance on P. polymyxa. None of the other antibiotic resistance cassettes were suitable because they did not confer useful levels of resistance in P. polymyxa. Nalidixic acid, used for counterselection against E. coli donors in conjugation procedures in the original Redirect protocol, also could not be used with P. polymyxa because it was found be inhibitory. Instead, polymyxin B was substituted and proved to be effective at killing E. coli but harmless to P. polymyxa at a concentration of 25 μg/ml (data not shown). Unexpectedly, however, it was subsequently determined that apramycin in combination with polymyxin B was lethal for P. polymyxa, thus also preventing use of Aprar as a selectable marker in conjugation experiments. Hence, a hybrid gene disruption cassette containing aac(3)IV, oriTRK2, and cat (Cmr) was constructed, allowing independent selection of Aprar in E. coli and Cmr in P. polymyxa. Like the disruption cassettes used in the Streptomyces system, the new Aprar Cmr oriT cassette employs the same 19- and 20-nt priming sequences for PCR amplification and contains the same FRT sites for FLP recombinase-mediated excision (Fig. 2A).

Disruption of fusA results in a fusaricidin nonproducer phenotype.

In order to assess the importance of the fusA gene fragment identified on cosmid Col-19 for biosynthesis of fusaricidins, we created fusA mutants by using an adaptation of the recently described Redirect technology and assessed the effect of the mutation on the antifungal activity against L. maculans.

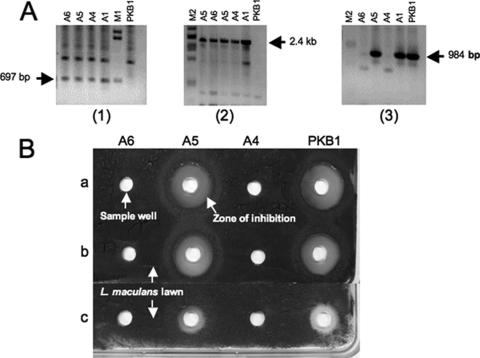

A segment (∼2.4 kb) internal to fusA was targeted for Redirect PCR primer design (Fig. 2B). Amplification of the Aprar Cmr oriT cassette using primers JRL-15RD and JRL-16RD (Fig. 2A) resulted in accumulation of the expected ∼2.5-kb DNA fragment, which was subsequently introduced by electroporation into E. coli BW25113 carrying both pIJ790 and the fusA-bearing cosmid Col-19. With selection for Aprar, Ampr, and Kanr, transformants carrying a mutated form of the Col-19 cosmid, in which the internal segment of fusA was deleted and replaced by the Aprar Cmr oriT cassette, were obtained (Fig. 2C). The desired gene disruption in Col-19 was verified by restriction analysis and PCR (see details below). The mutant Col-19 carrying the disrupted fusA allele was then passed through the nonmethylating E. coli host strain ET12567 and mobilized in trans by pUZ8002 into PKB1 via intergeneric conjugation. Among the resultant Cmr exconjugants, four independent mutants (A1, A4, A5, and A6) were isolated which gave a fragment of the expected size (697 bp) upon PCR using the aac(3)IV-specific primers SEJ18 and SEJ19 (Fig. 4A, gel 1). A second PCR analysis using primer SEJ19 together with a primer flanking the fusA locus, JRL14, showed that all four mutants had the disruption cassette correctly integrated into their chromosomes (Fig. 4A, gel 2). However, a third PCR analysis performed with primer JRL14 and a fusA-specific primer, JRL30, to test for deletion of the fragment internal to fusA showed that while no PCR products were obtained from mutants A4 and A6, mutants A1 and A5 both gave rise to the fusA-specific fragment (984 bp) that was expected to be amplified from only wild-type strain PKB1 (Fig. 4A, gel 3). This same fragment was also observed in the wild-type PKB1 strain, and the results indicated that a wild-type copy of fusA must still be present in mutants A1 and A5. Genomic DNA from the wild-type PKB1 strain and the four fusA mutants was also examined by Southern analysis to confirm the nature of the mutations. A 2.3-kb PstI fragment (Fig. 2D) hybridizing to a cat-specific probe was detected in the four mutant samples but not in the wild type, consistent with the expected gene replacement by the Aprar Cmr oriT cassette in all fusA mutants. However, when the same blot was probed with a PstI fragment internal to fusA from the region replaced by the Aprar Cmr oriT cassette (Fig. 2B), a hybridizing band of the expected size (2.85 kb) was seen in the wild-type sample and in the A1 and A5 mutants. No hybridization to the probe was seen in the A4 and A6 mutants (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate that disruption of fusA by the antibiotic resistance cassette in mutants A4 and A6 resulted from gene replacement via double crossover. However, in the A1 and A5 mutants, the entire mutant cosmid integrated into the chromosome by single crossover, resulting in both a wild-type copy and a mutant copy of fusA on their chromosomes.

FIG. 4.

(A) PCR verification of fusA mutants. Genomic DNA from four independent mutants, A1, A4, A5, and A6, as well as the wild-type PKB1 strain, was amplified using a pair of aac(3)IV-specific primers, SEJ18 and SEJ19 (gel 1), primer SEJ19 and a primer flanking the fusA locus, JRL14 (gel 2), and primer JRL14 and a fusA-specific primer, JRL30 (gel 3). See Fig. 2 for the locations of PCR primers. Lane M1, lambda DNA/BstEII marker; lane M2, lambda DNA/PstI marker. (B) Antifungal activities of the A4, A5, and A6 mutants carrying the fusA disruption compared to the activity of wild-type PKB1. All strains were grown in PDB-soy medium for 72 h, and then a well bioassay was used to evaluate antifungal activity against L. maculans. Row a, cell and spore pellet; row b, culture supernatant; row c, whole culture. Zones of inhibition were observed after 3 days of incubation.

The four fusA disruptants were cultivated in PDB-soy medium, along with the wild type, to assess production of fusaricidins. After 72 h, methanol extracts of the cells and spores, the culture supernatant, and the entire culture were tested for antifungal activity against L. maculans (Fig. 4B). Compared to wild-type strain PKB1, mutants A4 and A6 had completely lost the ability to produce antifungal material. In contrast, the two single-crossover mutants gave bioassay results indistinguishable from those obtained with the wild type (data not shown for A1).

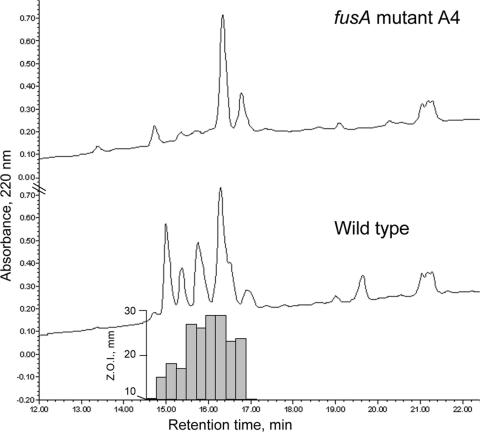

Partially purified methanol extracts of wild-type and fusA mutant A4 cultures grown on PDB-soy medium were also analyzed by HPLC. Although no authentic standards are available for the various analogs of fusaricidin, extracts from wild-type cultures showed a series of A220 peaks eluting between 15 and 17.5 min upon reversed-phase chromatography, and fractions corresponding to these peaks showed bioactivity against L. maculans, consistent with the presence of fusaricidins (Fig. 5). HPLC analysis of corresponding extracts from the fusA A4 mutant showed a simpler profile with several peaks missing in this area, and no bioactivity was detected in these or any other fractions. On this basis, we concluded that the fusA A4 mutant does not produce detectable fusaricidins and therefore that fusA is essential for biosynthesis of these antifungal peptide metabolites.

FIG. 5.

HPLC analysis of extracts from wild-type and fusA A4 mutant cultures. Methanol extracts of whole PDB-soy medium-grown cultures were partially purified before analysis by adsorption to a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. Concentrated bioactive material was then separated by reversed-phase HPLC with gradient elution. Fractions were collected across the elution profile and bioassayed against L. maculans. The bioassay sample wells were 10 mm in diameter, which was the minimum zone of inhibition (Z.O.I.) observable.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, fusaricidin-type antifungal antibiotics produced by P. polymyxa PKB1 were purified and characterized, but there was no genetic information regarding their biosynthesis. In the present study, we cloned and characterized an incomplete ORF, fusA, which appears to encode a segment of a peptide synthetase involved in biosynthesis of fusaricidins. Genetic disruption of fusA completely abolished the antifungal activity of PKB1 against L. maculans, confirming its participation in the synthesis of fusaricidins.

To clone the fusaricidin biosynthetic genes, we amplified peptide synthetase gene fragments from PKB1 to serve as probes to screen a genomic DNA library. Using one of the Thr-specific probes, two groups of hybridizing cosmid clones were identified. The DNA sequence information obtained from a representative member of the first group of clones indicated the presence of a Thr-specific module flanked on either side by Orn-specific modules. However, none of the other peptide metabolites described from P. polymyxa isolates contains Orn (2,5-diaminovaleric acid). Instead, the closely related compound DAB is found in several P. polymyxa peptide products (although not in fusaricidins), and so the modules identified as incorporating Orn may actually represent DAB-activating modules. Furthermore, polymyxin, a well-known peptide antibiotic from P. polymyxa, is the only one of the DAB-containing products that has a DAB-Thr-DAB amino acid sequence. On this basis, we postulated that the first group of cosmid clones may represent a polymyxin biosynthetic gene cluster. However, additional experimentation is clearly required before this can be firmly established.

Analysis of clone Col-19, the only member of the second group of clones, showed the presence of a partial ORF, fusA, corresponding to a deduced amino acid sequence (FusA) containing two modules typical of NRPSs. The predicted substrate specificities of the two A domains within FusA were consistent with the first two amino acids, Thr and Val, in the peptide moiety of fusaricidins. Additionally, an E domain linked to the second module was detected, suggesting the incorporation of d-Val into the peptide product at this location. Furthermore, the initial module of FusA has a C domain, which is not normally present in the initial modules of NRPSs except for lipopeptides, where it is presumed to be required for attachment of the lipid moiety. A C domain preceding the first module has been identified in all characterized lipopeptide synthetase systems from Bacillus, including the surfactin (2, 7), lichenysin (19), iturin A (35), and mycosubtilin (4) synthetases. Since the initial C domains catalyze the coupling of fatty acids, rather than amino acids, to the first amino acid of the peptide chain, they share features not found in other C domains, and so greater similarity is seen within this group than with other internal C domains. The primary structure of the fusaricidins has an N-terminal Thr residue acylated with a β-hydroxy fatty acid, as is also the case for surfactin. Thus, the high level of similarity between the first C domain of FusA and that of other lipopeptide synthetases further supports our assumption that fusA encodes at least the first two modules of fusaricidin synthetase.

In order to verify the role of fusA in biosynthesis of fusaricidins, targeted mutations were created on the chromosome of PKB1. In initial studies, the E. coli-based integrational vector pJH101 (6) carrying a short internal DNA fragment of fusA was used for gene disruption attempts. Insertion mutants, apparently resulting from single crossovers between the cloned fragment and the chromosomal copy of fusA, were isolated (data not shown), but they were unstable in the absence of antibiotic selection and reverted to the wild type. Therefore, a more efficient mutagenesis procedure for use in P. polymyxa was required. The specific approach used in this study is based on the PCR targeting system developed by Datsenko and Wanner (3) for use in E. coli and adapted for mutation of Streptomyces (8). In this approach, chromosomal genes cloned on a cosmid vector can be specifically disrupted in E. coli by recombination with a PCR-amplified antibiotic resistance cassette flanked by two 39-nt DNA sequences identical to the target gene. The presence of an oriT site in the disruption cassette permits conjugation to be used for subsequent transfer of the mutated cosmid from E. coli to the organism that is the source of the target gene. Compared to the electroporation procedure available for P. polymyxa (28), intergeneric transfer of DNA from E. coli to P. polymyxa by conjugation was found to be much more efficient for PKB1 (data not shown), and therefore the use of conjugation to introduce the mutated cosmid into P. polymyxa was an attractive feature of this approach. To adapt the Redirect technology for P. polymyxa, an antibiotic resistance cassette functional in P. polymyxa was required. For this purpose we used the cat gene from a Staphylococcus plasmid, one of the very few selectable markers useful in PKB1, to construct a special hybrid disruption cassette containing two antibiotic resistance genes, aac(3)IV (Aprar) for selection in E. coli and cat (Cmr) for selection in P. polymyxa. Although Aprar can be selected directly in P. polymyxa, upon subsequent transfer of the mutant cosmid into P. polymyxa by conjugation, no exconjugants could be recovered in the presence of both apramycin and polymyxin B, and P. polymyxa was found to be sensitive to this combination of antibiotics. Therefore, inclusion of the cat gene in the disruption cassette was necessary to allow use of chloramphenicol for selection of P. polymyxa exconjugants in which the mutant fusA allele had integrated into the chromosome by homologous recombination, together with polymyxin B to counterselect E. coli donors.

The usefulness of this protocol in P. polymyxa was demonstrated by the generation of fusaricidin biosynthesis mutants in which fusA was inactivated by replacement of an internal fragment of fusA with the gene disruption cassette. The complete loss of antifungal activity in these mutants provides evidence that fusA is part of the fusaricidin biosynthetic gene cluster and is essential for the production of fusaricidins. Analysis of two additional mutants isolated during this study indicated that they were the result of single crossovers, and when assayed for production of fusaricidins, they showed production levels similar to those of the wild type. Whether the production of wild-type levels of fusaricidins by single-crossover mutants resulted from their reversion to the wild type during growth in the absence of antibiotic selection or from the presence of both mutant and wild-type copies of fusA on their chromosomes was not determined. To our knowledge, this represents the first reported use of PCR targeting for disruption of genes in Paenibacillus and provides a valuable new technique for generating specific mutations in this and perhaps other related genera.

When wild-type P. polymyxa strain PKB1 is grown on PDA or other carbohydrate-rich media, the colonies have a thick capsular layer of slime, presumably due to production of extracellular levan (9). Interestingly, when the fusA double-crossover mutants were grown on PDA plates, the colonies produced noticeably larger amounts of capsular slime than the amount observed for either wild-type strain PKB1 or the single-crossover mutants. This observation may indicate that there is a relationship between polysaccharide synthesis and antibiotic production in P. polymyxa.

The results of this study provide evidence of a nonribosomal mechanism for the biosynthesis of fusaricidins, which are antifungal lipopeptides from P. polymyxa PKB1. Cloning of the NRPS genes associated with production of fusaricidins should allow genetic manipulation of peptide production to be undertaken and could increase the antifungal activity of this organism. The fusaricidins are a mixture of at least 12 cyclic depsipeptides, and bioassay results suggest that the various analogs differ in their antimicrobial activities against L. maculans and other indicator organisms (1, 15, 16, 20, 21). Recently, alterations of A domain selectivity have been achieved by point mutations of the specificity-conferring codes within the surfactin synthetases (5). This site-directed mutagenesis approach offers the potential to bias the specificity of the relevant fusaricidin synthetase modules, thereby increasing the yield of fusaricidin analogs associated with the greatest antifungal activity. Work is in progress to determine the complete nucleotide sequence of the fusaricidin biosynthetic gene cluster as a first step towards this goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Alberta Agricultural Research Institute.

We thank A. Wong for helpful advice about the Redirect technology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beatty, P. H., and S. E. Jensen. 2002. Paenibacillus polymyxa produces fusaricidin-type antifungal antibiotics active against Leptosphaeria maculans, the causative agent of blackleg disease of canola. Can. J. Microbiol. 48:159-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosmina, P., F. Rodriguez, F. de Ferra, G. Grandi, M. Perego, G. Venema, and D. van Sinderen. 1993. Sequence and analysis of the genetic locus responsible for surfactin synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:821-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duitman, E. H., L. W. Hamoen, M. Rembold, G. Venema, H. Seitz, W. Saenger, F. Bernhard, R. Reinhardt, M. Schmidt, C. Ullrich, T. Stein, F. Leenders, and J. Vater. 1999. The mycosubtilin synthetase of Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633: a multifunctional hybrid between a peptide synthetase, an amino transferase, and a fatty acid synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13294-13299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eppelmann, K., T. Stachelhaus, and M. A. Marahiel. 2002. Exploitation of the selectivity-conferring code of nonribosomal peptide synthetases for the rational design of novel peptide antibiotics. Biochemistry 41:9718-9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari, F. A., A. Nguyen, D. Lang, and J. A. Hoch. 1983. Construction and properties of an integrable plasmid for Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 154:1513-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuma, S., Y. Fujishima, N. Corbell, C. D'Souza, M. M. Nakano, P. Zuber, and K. Yamane. 1993. Nucleotide sequence of 5′ portion of srfA that contains the region required for competence establishment in Bacillus subtilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:93-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han, Y. W. 1989. Levan production by Bacillus polymyxa. J. Ind. Microbiol. 4:447-452. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopwood, D. A., M. J. Bibb, K. F. Chater, T. Kieser, C. J. Bruton, H. M. Kieser, D. J. Lydiate, C. P. Smith, J. M. Ward, and H. Schrempf. 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 11.Horinouchi, S., and B. Weisblum. 1982. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pC194, a plasmid that specifies inducible chloramphenicol resistance. J. Bacteriol. 150:815-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito, M., and Y. Koyama. 1972. Jolipeptin, a new peptide antibiotic. Isolation, physico-chemical and biological characteristics. J. Antibiot. 25:304-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, M., and Y. Koyama. 1972. Jolipeptin, a new peptide antibiotic. The mode of action of jolipeptin. J. Antibiot. 25:309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen, G. R., and M. J. Bibb. 1993. Derivatives of pUC18 that have BglII sites flanking a modified multiple cloning site and that retain the ability to identify recombinant clones by visual screening of Escherichia coli colonies. Gene 124:133-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kajimura, Y., and M. Kaneda. 1996. Fusaricidin A, a new depsipeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus polymyxa KT-8. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, structure elucidation and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 49:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kajimura, Y., and M. Kaneda. 1997. Fusaricidins B, C, and D: new depsipeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus polymyxa KT-8, isolation, structure elucidation and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 50:220-228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz, E., and A. L. Demain. 1977. The peptide antibiotics of Bacillus: chemistry, biogenesis, and possible functions. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:449-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharbanda, P. D., J. Yang, P. H. Beatty, S. E. Jensen, and J. P. Tewari. 1997. Potential of a Bacillus sp. to control blackleg and other diseases of canola. Phytopathology 87:S51. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konz, D., S. Doekel, and M. A. Marahiel. 1999. Molecular and biochemical characterization of the protein template controlling biosynthesis of the lipopeptide lichenysin. J. Bacteriol. 181:133-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda, J., T. Fukai, M. Konishi, J. Uno, K. Kurusu, and T. Nomura. 2000. LI-F antibiotics, a family of antifungal cyclic depsipeptides produced by Bacillus polymyxa L-1129. Heterocycles 53:1533-1549. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurusu, K., K. Ohba, T. Arai, and K. Fukushima. 1987. New peptide antibiotics LI-F03, F04, F05, F07, and F08, produced by Bacillus polymyxa. Isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 40:1506-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacNeil, D. J., K. M. Gewain, C. L. Ruby, G. Dezeny, P. H. Gibbons, and T. MacNeil. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marahiel, M. A., T. Stachelhaus, and H. D. Mootz. 1997. Modular peptide synthetases involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Chem. Rev. 97:2651-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima, N., S. Chihara, and Y. Koyama. 1972. A new antibiotic, gatavalin. I. Isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 25:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paget, M. S., L. Chamberlin, A. Atrih, S. J. Foster, and M. J. Buttner. 1999. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 181:204-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peypoux, F., J. M. Bonmatin, and J. Wallach. 1999. Recent trends in the biochemistry of surfactin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:553-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pichard, B., J. P. Larue, and D., Thouvenot. 1995. Gavaserin and saltavalin, new peptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus polymyxa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 133:215-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosado, A., G. F. Duarte, and L. Seldin. 1994. Optimization of electroporation procedure to transform Bacillus polymyxa SCE2 and other nitrogen-fixing Bacillus. J. Microbiol. Methods 19:1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salowe, S. P., E. N. Marsh, and C. A. Townsend. 1990. Purification and characterization of clavaminate synthase from Streptomyces clavuligerus: an unusual oxidative enzyme in natural product biosynthesis. Biochemistry 29:6499-6508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 31.Seldin, L., J. D. van Elsas, and E. G. C. Penido. 1983. Bacillus nitrogen fixers from Brazilian soils. Plant Soil 70:243-255. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sogn, J. A. 1976. Structure of the peptide antibiotic polypeptin. J. Med. Chem. 19:1228-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stachelhaus, T., H. D. Mootz, and M. A. Marahiel. 1999. The specificity-conferring code of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem. Biol. 6:493-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tosato, V., A. M. Albertini, M. Zotti, S. Sonda, and C. V. Bruschi. 1997. Sequence completion, identification and definition of the fengycin operon in Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology 143:3443-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuge, K., T. Akiyama, and M. Shoda. 2001. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of the iturin A operon. J. Bacteriol. 183:6265-6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turgay, K., and M. A. Marahiel. 1994. A general approach for identifying and cloning peptide synthetase genes. Pept. Res. 7:238-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West, J. S., P. D. Kharbanda, M. J. Barbetti, and B. D. L. Fitt. 2001. Epidemiology and management of Leptosphaeria maculans (phoma stem canker) on oilseed rape in Australia, Canada and Europe. Plant Pathol. 50:10-27. [Google Scholar]