Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is an autochthonous member of diverse aquatic ecosystems around the globe. Collectively, the genomes of environmental V. cholerae strains comprise a large repository of encoded functions which can be acquired by individual V. cholerae lineages through uptake and recombination. To characterize the genomic diversity of environmental V. cholerae, we used comparative genome hybridization to study 41 environmental strains isolated from diverse habitats along the central California coast, a region free of endemic cholera. These data were used to classify genes of the epidemic V. cholerae O1 sequenced strain N16961 as conserved, variably present, or absent from the isolates. For the most part, absent genes were restricted to large mobile elements and have known functions in pathogenesis. Conversely, genes present in some, but not all, California isolates were in smaller contiguous clusters and were less likely to be near genes with functions in DNA mobility. Two such clusters of variable genes encoding different selectable metabolic phenotypes (mannose and diglucosamine utilization) were transformed into the genomes of environmental isolates by chitin-dependent competence, indicating that this mechanism of general genetic exchange is conserved among V. cholerae. The transformed DNA had an average size of 22.7 kbp, demonstrating that natural competence can mediate the movement of large chromosome fragments. Thus, whether variable genes arise through the acquisition of new sequences by horizontal gene transfer or by the loss of preexisting DNA though deletion, natural transformation provides a mechanism by which V. cholerae clones can gain access to the V. cholerae pan-genome.

Vibrio cholerae, the cause of Asiatic cholera, is autochthonous to a wide variety of marine and estuarine habitats. Readily detected in warm estuarine waters around the globe (33), V. cholerae associates with diverse organisms, including zooplankton, phytoplankton, and fish (18, 19, 45). Environmental factors, most notably water temperature, that are associated with the growth and survival of V. cholerae in the aquatic environment are correlated with the seasonal epidemic patterns of cholera in humans (34, 40).

The ability of V. cholerae to colonize multiple ecological niches is consistent with its extensive phenotypic and genotypic diversity. Over 200 serogroups of V. cholerae have been identified (12), and isolates have been found to be genetically and biochemically diverse (1, 3, 8, 11). Even when restricting the analysis to toxigenic isolates, significant interannual and interepidemic diversity has been documented (12, 61) for both gene content and allelic variation (8, 9, 21, 29, 42). The extent of variability is greater when considering nonepidemic pathogenic isolates and even more so with nonpathogenic environmental isolates (3, 11, 23).

The extensive genomic diversity described for environmental V. cholerae isolates using genomic markers and sequence analysis (13) is consistent with patterns described for the intraspecific variability of other Vibrio species and also of more divergent bacteria. By comparing the sequence of the hsp60 gene with that of the total genome size, Thompson et al. recently demonstrated that a coastal Vibrio splendidus population contains hundreds of genotypes per milliliter of seawater, with each genotype present at <1 ml−1 (55). Detailed analysis of the fully sequenced genomes from two pathogenic Vibrio vulnificus isolates points to significant genomic plasticity, much of which is due to large genomic islands specific to one strain (44). A comparison of the whole genome sequences of eight isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae led to the division of the S. agalactiae pan-genome into universally conserved genes that comprise the core genome of this species and sporadically conserved dispensable genes. Computational modeling indicates that the set of dispensable genes, present in some but not all S. agalactiae isolates, is inordinately large (54).

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and DNA sequence analysis show that V. cholerae O1 and O139 toxigenic isolates from humans with cholera are phylogenetically tightly clustered with each other within V. cholerae populations. Some clones, both toxigenic and nontoxigenic, have been observed to persist in the environment for years (3, 11, 52). Nonetheless, results from both genome-wide and single-locus analyses point to extensive recombination between V. cholerae lineages (4, 5, 29, 30, 52). The emergence in 1992 of epidemic isolates of serogroup O139 exemplifies this phenomenon. While the mechanism of gene transfer is still unclear, current evidence suggests that the O1 progenitor of the O139 epidemic strains had acquired new O-antigen genes from an environmental V. cholerae strain of serogroup O22 and that these genes had been recombined into the O1-encoding locus (57). Thus, while a small number of V. cholerae clones have the combination of genes necessary to efficiently infect humans (3), these organisms can also acquire DNA encoding novel functions from nontoxigenic lineages of environmental V. cholerae strains (43).

Several mechanisms have been described by which new DNA from potentially very distant sources can be introduced into the genome of a V. cholerae lineage. The genes encoding the cholera enterotoxin reside on a functional prophage (58). Furthermore, Vibrio pathogenicity islands, VPI-1 and VPI-2, which encode other virulence determinants, bear hallmarks of recent acquisition by lateral gene transfer (20, 26). An integrating conjugative transposon, SXT, has been detected in clinical and environmental isolates (59). This transposon can mobilize not only itself but also plasmids and linked chromosomal DNA (17). Recently, a more generalized mechanism for genetic exchange between different V. cholerae strains has been described. V. cholerae O1 becomes competent for natural transformation when grown on chitin (36), a nutritive substrate which it colonizes in aquatic habitats (18). While the acquisition of sequences by natural competence, which requires homologous recombination, is expected to be restricted to donors that are closely related to V. cholerae, it is potentially capable of transforming any part of the genome between V. cholerae lineages. Transformation proceeds without the requirement for specialized sequence elements (e.g., repeats) or for genes encoding dedicated functions (e.g., integrases). Genetic exchange via transformation has been implicated in the extensive diversity observed for Neisseria spp. (32) and Helicobacter pylori populations (10). In addition to these mechanisms by which lineages can gain new sequences, gene loss through deletion (49) can play a role in generating diversity.

In this study, we used comparative genome hybridization (CGH) to identify genes that are conserved and genes that vary between 41 non-O1/O139 environmental V. cholerae strains isolated from eight ecologically diverse sites along the central California coast. We demonstrate the transfer of two clusters of variable genes encoding different metabolic functions into the genomes of California isolates induced to competence by growth on chitin. These results suggest that recombination through natural transformation can facilitate the exchange of variable genes between different V. cholerae lineages residing in the same aquatic habitat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Isolation and characterization of the California Vibrio cholerae strains used here are described in the report by Keymer et al. (27). O1 (N16961 [25], VCX-B21 [31], A1552 [60], O395 [53]) and O139 (MO3 [41]) reference strains have been described previously.

Comparative genome hybridization analysis of gene content.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) samples from isolates and the N16961 reference strain were prepared in parallel from overnight cultures grown in LB (2) using QIAGEN DNeasy columns according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was concentrated by ethanol precipitation, labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 by primer extension (6), and then mixed, purified, and concentrated using Microcon YM-10 centrifugal concentrators. PCR amplicon microarrays with spots for 3,357 of 3,891 annotated genes in V. cholerae N16961 were hybridized as described in reference 37. Only spots with a regression correlation of >0.6 were considered for analysis. For genes with multiple probes, log2(isolate/N16961) values were averaged after normalization.

A two-step protocol was designed to (i) identify genes which were highly conserved in all isolates and then (ii) normalize signal intensity based only on universally present genes. This strategy allows normalization using the majority of the probes on the array while avoiding biasing the normalization constant based on the number of genes missing from any given isolate. First, channel 2 (typically Cy3) intensity was adjusted so the log2 ratio of the net signal from features for genes encoding ribosomal proteins was equal to 0. The 2,222 genes for which the log2(isolate/N16961) was >1 for all isolates were considered always conserved. Each array was then renormalized based on these 2,222 always-conserved genes, resulting in a biphasic distribution of the normalized log2 ratio of hybridization intensities with a large, narrow peak (conserved genes) centered near 0 and a small, wider peak (divergent genes) centered at −2 to −3.

For each isolate genome, genes were categorized as “positive,” “negative,” or “uncertain,” corresponding to “present,” “absent,” and “uncertain,” respectively, as described in reference 46. For each array, we calculated the median for the two sets of genes in which at least two chromosomally adjacent genes had log2(isolate/N16961) values of ≤−1.5 (negative) or >−1.5 (positive). Genes were then determined to be (“called”) negative if the log2(isolate/N16961) value was less than or equal to the mediannegative minus 2 standard deviations and positive if log2(isolate/N16961) was greater than or equal to medianpositive plus 2 standard deviations. The final determination (“call”) for each gene within a genome was based on the consensus of calls from three arrays.

The hybridization data describing the conservation of genes within each isolate genome were aggregated to examine the pattern of conservation across the sampled California V. cholerae isolates. Considering all of the California isolates, genes were grouped into the categories “conserved” (no isolate called negative), “absent” (no isolate called positive), or “variable” (some isolates called negative and others positive). As a quality control measure, genes with calls in fewer than 70% of isolates were categorized as “uncalled.” The 70% cutoff was introduced to prevent categorizing genes based on unreliable hybridization data. Some genes were found to have hybridization ratios between the cutoffs for being called “positive” and “negative” in a large proportion of isolates. These intermediate hybridization ratios could have arisen from either technical (e.g., nonspecific background hybridization, or spot contamination) or biological (e.g., paralog hybridization) causes. This microarray data cannot distinguish between these, so the 70% cutoff was imposed to eliminate these genes from the analysis.

It should be noted that the categories used here considered a gene missing from just one isolate to be variable, while genes missing from as many as 5% of isolates were considered part of the “core” genome, as defined by Keymer et al. (27), for comparison to previous analyses. The lower threshold was used in this study to maximize detection of variable genes.

Clusters were defined as contiguous, absent, and/or variable genes separated by no more than one unprobed or uncalled gene for N16961. Uncalled or unprobed genes within or immediately upstream of clusters were included in the cluster. This approach requires the assumption of synteny between the N16961 and the California isolate genomes, an assumption supported by the PCR validation and transformation results presented below.

Growth experiments.

Vibrio isolates were grown at 37°C in M9 (2) supplemented with minimum essential medium vitamins (Invitrogen), 0.001% Casamino acids, and the indicated carbon source at 0.2%. Plates were solidified with 2% Nobel agar. Cultures were inoculated in triplicate at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 from washed, overnight cultures grown in M9 with 0.5% sodium lactate. Plates were inoculated by frogging from washed, overnight cultures diluted to an OD600 of 0.1.

Transformation experiments.

Transformations were performed on crab shell as described previously (36). gDNA (2 μg) was added to washed biofilms grown on crab shell for 18 h, and then transformants were selected 18 to 20 h later. All strains grew equally well under transformation conditions. Transformants were selected on LB medium with antibiotic or M9 plus a carbon source. Transformation efficiency was calculated as transformant CFU/total CFU on LB or M9 plus N-acetylglucosamine. Newly acquired DNA was detected by PCR using three primers, two flanking the variable region and one within. The recombined DNA was mapped based on improved hybridization to an oligonucleotide probe microarray containing probes for all the annotated protein-encoding genes in strain N16961. gDNA samples from transformants and parental strain W6G were labeled as described above and hybridized as described in reference 36. Data from four arrays were averaged for each transformant. Recombined DNA was detected as improved hybridization at probes directed against genes absent from or containing sequence differences in isolate W6G. Recombination junctions were confirmed and mapped to higher resolution by sequencing PCR products.

RESULTS

Comparative genome hybridization identifies genes common to and variable between California isolates.

Over the course of an 18-month sampling period, we recently collected 41 non-O1/O139 V. cholerae isolates from eight central California coastal sites (27). We specifically chose to study isolates from a region free of disease to explore genome variability outside of the known pathogenicity islands. We reasoned that genes common to these environmental strains likely specify functions necessary for success in aquatic habitats, whereas those that vary between strains may encode functions specific for particular niches within these habitats. To identify V. cholerae O1 genes that vary among the isolates, we competitively hybridized genomic DNA from each environmental isolate with DNA from the V. cholerae O1 El Tor sequenced strain N16961 to amplicon microarrays designed to probe genes in the published N16961 genome sequence (16). For each hybridized microarray (see Table S1 in the supplemental material and the Stanford MicroArray database, http://smd.stanford.edu), every gene was assigned to one of three classes, “positive,” “negative,” or “uncertain,” based on a largely binary distribution of relative hybridization intensities (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). We used diagnostic PCR from flanking, conserved regions to evaluate a sample of about 20 genes which had been classified as negative and found that typically, the entire predicted open reading frame (ORF) or ORFs were missing from the isolate. In only one case, in which a definitive PCR result was obtained, was there disagreement between the PCR analysis and the CGH analysis. The VC2423 locus (pilA) was called negative by the CGH analysis, but there is a deeply divergent, putative pilin-encoding gene here in at least some isolates (data not shown).

These individual hybridization results allowed us to categorize each ORF according to its representation within the collection of 41 California isolates (Table 1). A total of 2,727 genes (81% of 3,357 genes probed) gave positive hybridization results for all tested isolates. These compose the “conserved” gene set because they are universally present within all of the tested environmental isolates and in the N16961 V. cholerae O1 sequenced strain. We identified 133 genes (4.0%) which were present in the genome of the V. cholerae O1 sequenced strain N16961 but which were not detected in any of the California isolates. These compose the “absent” gene set. Finally, we identified 364 genes (11%) which were present in the V. cholerae sequenced strain and in some, but not all, of the California isolates. These were designated the “variable” gene set since their presence varies across the California isolate collection. In addition, 133 (4.0%) genes were not categorized because they gave a definitive hybridization result in less than 70% of the tested isolates. That these genes gave ambiguous hybridization results in a large portion of isolates suggested that their microarray probes were not specific enough to make confident calls. These genes were assigned to the “uncalled” gene set (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Number (fraction) of probed N16961 genes conserved, absent, and variable in California Vibrio cholerae isolates

| Gene category | Total no. of genes found (fraction) | No. of genes found at indicated location (fraction)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome 1 | Chromosome 2 | Superintegron | ||

| Conserved | 2,727 (0.81) | 2,102 (0.86) | 625 (0.69) | 2 (0.02) |

| Absent | 133 (0.04) | 97 (0.04) | 36 (0.04) | 26 (0.21) |

| Variable | 364 (0.11) | 204 (0.08) | 160 (0.18) | 58 (0.46) |

| Uncalled | 133 (0.04) | 52 (0.02) | 81 (0.09) | 39 (0.31) |

| Total probed | 3,357 | 2,455 | 902 | 125 |

The strain collection in this study differs from those studied previously by microarray CGH (8, 9) in that it is larger and was collected from coastal waters in a region without endemic disease, thus sampling organisms whose genomes have not been subjected to selection for growth in the human intestine. Together, these differences led us to predict that the California isolate collection would be at least as divergent from the V. cholerae N16961 O1 sequenced strain reference as the isolates studied previously. To test this, we compared the sets of genes scored as absent or variable in our isolates with the analogous gene sets described in reference 9, which mainly includes pathogenic but nontoxigenic strains. Of the 3,357 genes probed in both studies, 2,703 (81%) genes were conserved in both strain collections and 299 (8.9%) were variably present in both collections. There are substantially more genes that are variable among the California isolates but conserved among the isolates described in reference 9 than there are genes conserved among the California isolates but variable among the isolates described in reference 9. Two hundred N16961 genes (6.0%) reported as conserved in reference 9 varied in the genomes of environmental V. cholerae from California, while only 22 genes (0.66%) previously described as variable were conserved in this set of isolates.

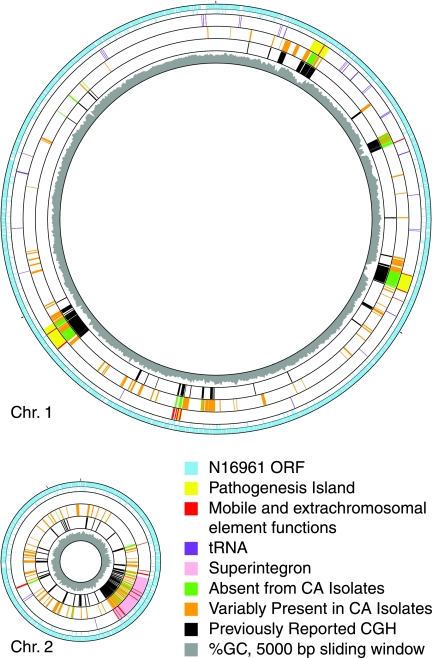

To gain a better understanding of the distribution of the different gene sets across the two V. cholerae chromosomes, we mapped the location of genes in the conserved, absent, and variable categories onto the fully sequenced genome of N16961 (Fig. 1). As expected, given the high variability of chromosome 2 (8), it is more variable than chromosome 1 among California isolates (Table 1). In particular, multiple large clusters of absent and variable genes are found nearly adjacent to each other at the integron on chromosome 2 (VCA0296 to VCA0506) and in two additional clusters predicted to encode transposases (VCA0198 to VCA0200 and VCA0790 to VCA0795).

FIG. 1.

Genes variably present in or absent from all California Vibrio cholerae isolates mapped onto N16961 chromosomes. Circle one shows each of the protein-coding genes (16) in reference strain N16961 probed in this study (blue); circle two shows genes not probed. Circle three shows genome landmarks. Absent (green) and variable (orange) genes are plotted in the fourth circle. Conserved and uncalled genes are not shown. Circle five shows genes identified by previous CGH studies as missing from at least one V. cholerae isolate (black) (8, 9). Circle six shows the percentage of G+C (gray) in a 5,000-bp window in 1,000-bp steps, determined using GACK software (28). Generated with GenoMap (47).

The genes that are completely absent from the California isolates are distributed around the N16961 genome differently than the genes that are variable among California isolates. N16961 genes which are absent from all California isolates tend to be located within large regions of variability. Absent genes were found in 29 clusters with a median size of 21 contiguous N16961 ORFs. Among these are three clusters on chromosome 1 with known functions in pathogenesis: VPI-1 (VC0817 to VC0847), cholera toxin prophage (VC1456 to VC1464), and VPI-2 (VC1758 to VC1809). Two additional large clusters which contain absent genes are found on chromosome 1. One of these (VC0233 to VC0270) directs the biosynthesis of the O1 antigenic determinant of the classical and El Tor epidemic biotypes, whereas the other (VC0490 to VC0516) appears to be of phage origin and is a superset of Vibrio seventh pandemic island 2 (VSP-II) (8). Interestingly, we found that VSP-I, previously reported as specific to El Tor strains, is present in several California isolates. By contrast, genes in the variable gene set, which are located within 136 clusters, are more often found as singletons or in small clusters flanked by regions of conserved sequences. The median size of these regions, seven contiguous genes, is significantly smaller than that for genes in the absent gene set (Student's t test, P = 5e-20).

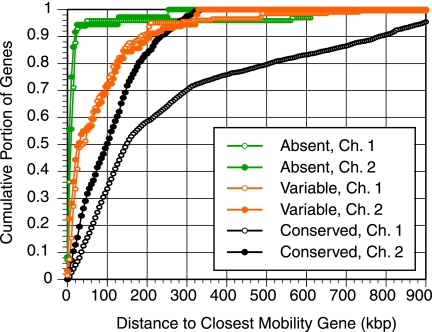

Some of the genes that are present in the sequenced strain N16961 but absent from California isolates are known to have been acquired on transmissible genetic elements which encode dedicated machinery for gene exchange. Notable among these are the genes encoding cholera toxin (VC1456 to VC1464), which reside within a prophage (58). To discover if this association is a common feature of genes which are present in N16961 but absent in California isolates, we determined if they are more likely than genes in the variable gene set to have chromosome positions near mobility genes. We measured the distance between each gene in the N16961 genome and the closest gene annotated to encode mobile and extrachromosomal element functions (Fig. 2). Assuming synteny, these values are also a good approximation for the distances in the California isolate genomes. Nearly all (94%) of the genes which are present in the N16961 sequenced strain, but absent in California isolates, fall within 40 kbp of a gene specifying a mobility function in N16961, a distance that corresponds to the size reported for several vibriophages (15). By contrast, only 52% of genes whose presence varies among California isolates and 16% of genes conserved in all isolates meet this criterion (Fig. 2). Furthermore, analysis of this association showed that differences in cluster size and distance from a coding region for a mobile genetic element parallel differences in the G+C content of genes in the absent, conserved, and variable gene sets. Genes absent from California isolates but present in the N16961 genome were found to have a median G+C content of 39.3% compared to the median G+C content of 49.0% for conserved genes. The lower G+C content of the former is largely due to the fact that they are usually associated with pathogenicity islands or phage and suggests that they were recently acquired by the epidemic lineages (16, 46). Genes that vary between California isolates have an intermediate G+C content of 45.4%. The same pattern is observed when using more nuanced methods which use G+C content as only one of several factors to estimate the probability of any gene having been introduced into the V. cholerae genome by horizontal transfer (14, 56). When comparing our CGH results to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) predictions (56), genes categorized as absent are most likely to be predicted to have originated by HGT (79%), and conserved genes are least likely (3.2%). Variable genes fall in between (34%). This reflects the fact that while most variable genes are unassociated with known mobile elements and pathogenicity islands, a portion are found in or near known islands.

FIG. 2.

Distance to mobility genes. The distance from the midpoint of each gene probed by CGH to the midpoint of the closest N16961 gene annotated as “mobile and extrachromosomal element functions” (16) is plotted in a cumulative histogram. Absent (green), variable (orange), and conserved (black) genes are plotted by chromosome. Because the chromosomes vary in size, the maximum possible distances are 1,481 kbp for chromosome 1 (Ch. 1) and 536 kbp for Ch. 2. This, along with uneven distribution of mobility genes, accounts for much of the differences between the shapes of the curves for the conserved genes.

The variable and absent gene sets both include many genes encoding hypothetical proteins and structures on the cell surface, but further analysis of the annotations for these gene sets disclosed important differences. Nearly one-third (29%) of the annotated genes absent from all the California isolates encode pathogenesis functions, while less than 2% of variable genes do so. Instead, annotations for genes within the variable gene set are rich with functions in chemotaxis and small molecule transport: more than 20% of genes that vary between the California isolates encode chemotaxis and small molecule transport functions compared to only 5% for absent genes and 11% for the N16961 genome as a whole. We conclude that the most consistent difference between California environmental V. cholerae and epidemic strains lies in their pathogenicity determinants. By contrast, the California isolates differ from each other in genes encoding functions mediating their interaction with the chemical environment.

Variable regions encoding metabolic functions are mobile via natural competence and transformation.

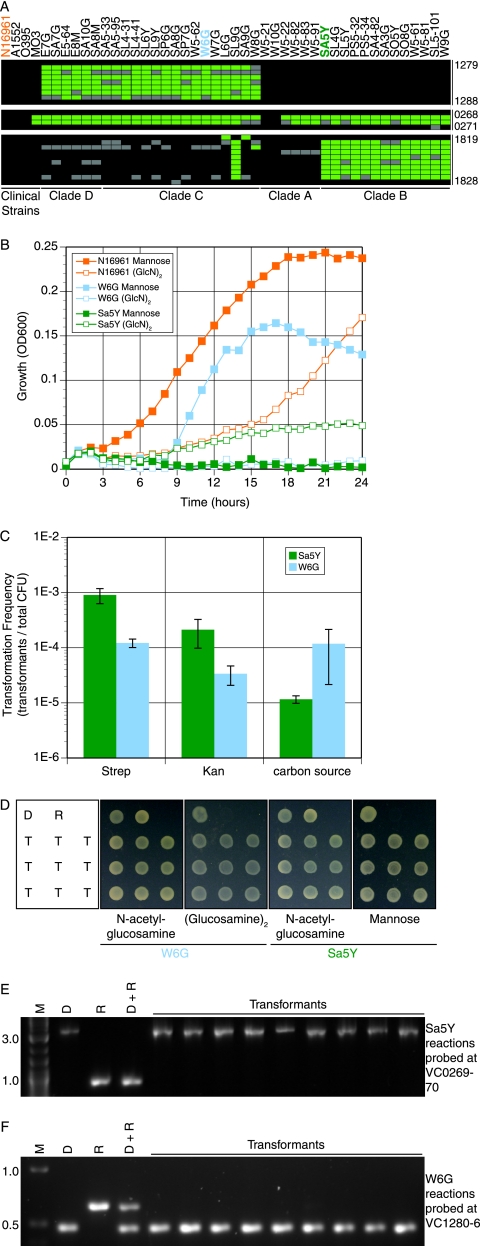

In the preceding section, CGH was used to study 41 California environmental isolates to identify genes in the conserved, absent, and variable gene sets. Reports of frequent interlineage recombination among V. cholerae (3, 5, 29) led us to ask if variable genes outside of known mobile elements can be transferred from one genome to another via natural competence. We focused on two gene clusters (VC1280 to VC1286 and VC1820 to VC1827 in the genome of strain N16961) that encode different metabolic functions and vary between California isolates. These clusters are of interest because their presence or absence in California isolates was found to be significantly associated with water temperature (27), one of the physical parameters measured at the time of sampling. Strains simultaneously positive for gene cluster VC1820 to VC1827 and negative for VC1280 to VC1286 (e.g., strain W6G, shown in Fig. 3A) were associated with cold water. By contrast, strains positive for VC1280 to VC1286 and negative for VC1820 to VC1827 were more often isolated from warmer water (e.g., strain Sa5Y).

FIG. 3.

Transformation of variable loci. (A) Positive (black), negative (green), or uncertain (gray) genes at three loci on chromosome 1 for each isolate genome. Strains are grouped by overall genomic similarity based on a report by Keymer et al. (27). (B) Growth in M9 with 0.001% amino acids and 0.2% mannose (filled symbols) or (GlcN)2 (open symbols). W6G (blue) lacks genes VC1280 to VC1286. Sa5Y (green) lacks both VC0269 to VC0270 and VC01820 to VC01827. N16961 (orange) encodes all three loci. (C) Isolates Sa5Y (green) and W6G (blue) were grown on crab shell and transformed with gDNA from strain VCXB21. Transformants were selected on LB medium containing the indicated antibiotic or M9 with (GlcN)2 (W6G) or mannose (Sa5Y). (D) Metabolic phenotypes of transformants were confirmed by growth on M9 containing the indicated carbon source. D, gDNA donor strain; R, recipient isolate; T, nine independent transformants. (E and F) The selected locus transformed from the donor strain into the recipient isolate was detected by PCR. M, molecular weight marker (kbp). (E) Probes VC0269 to VC0270 transformed into Sa5Y using primers in VC0268, an intervening gene present in Sa5Y but not in VCXB21, and VC0271. (F) Probes VC1280 to VC1286 transformed into W6G using primers in VC1279, VC1280, and VC1287.

The metabolic roles of these gene clusters were studied by growth experiments. The VC1280-to-VC1286 cluster in strain N16961 was reported to encode proteins required for the uptake and metabolism of a glucosamine dimer (GlcN)2 (37). This functional role was corroborated by demonstrating that strain W6G, which lacks VC1280 to VC1286, does not grow in a medium containing (GlcN)2 as the carbon source (Fig. 3B). By contrast, strain Sa5Y, which has cluster VC1280 to VC1286, grows, albeit poorly, on (GlcN)2. N16961 also has the VC1280-to-VC1286 cluster and grows on (GlcN)2 (Fig. 3B).

The cluster VC1820 to VC1827 is annotated as encoding, among other functions, mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (VC1827), which catalyzes the interconversion of fructose-6-phosphate and mannose-6-phosphate. In addition to the VC1827 locus, the N16961 genome contains a second gene (VC0269) which also is predicted to encode a mannose-6-phosphate isomerase. However, CGH results indicate that VC0269 is missing from W6G and Sa5Y and from 37 other California isolates (Fig. 3A). The absence of both mannose-6-phosphate isomerase genes VC1827 and VC0269 from Sa5Y likely explains its failure to grow in a medium containing mannose as the sole carbon source (Fig. 3B). By contrast, strain W6G, which retains the VC1820-to-VC1827 gene cluster, grows on a mannose-containing medium. The N16961 sequenced strain, which has both of the mannose-6-phosphate isomerase genes, also grows on a mannose-containing medium.

In a prior report from our laboratory, Meibom et al. used laboratory strains of V. cholerae O1 El Tor and antibiotic resistance genes to establish the phenomenon of chitin-induced natural transformation as a mechanism of genetic exchange in this species (36). However, that report also showed that not all V. cholerae strains can be transformed in this manner and that in some strains this was shown to be due to a mutation in the quorum-sensing regulator hapR (36). To determine if W6G and Sa5Y can acquire genes by chitin-induced natural transformation, these California isolates were individually grown as biofilms on a crab shell fragment in artificial seawater. Then, we added genomic DNA from strain VCXB21 (31), a kanamycin- and streptomycin-resistant derivative of the N16961 sequenced strain. The resulting antibiotic-resistant transformants of W6G and Sa5Y were selected on media containing either kanamycin or streptomycin, and the transformation efficiencies were determined. W6G and Sa5Y were able to acquire the kanamycin and streptomycin-resistant loci encoded in gDNA from VCXB21 (Fig. 3C). Transformation efficiencies of W6G and Sa5Y for the acquisition of kanamycin resistance, conferred by neoR integrated upstream of lacZ, were comparable to those reported for laboratory strains. Streptomycin resistance, conferred by a spontaneous mutation, can be transformed into the two California environmental isolates with an efficiency 5- to 10-fold higher than that of kanamycin resistance.

These results showed that W6G and Sa5Y could acquire genes by chitin-induced natural transformation. These strains then were tested to determine if they can use chitin-induced natural transformation to acquire the VC1280-to-VC1286 and VC1820-to-VC1827 gene clusters and corresponding metabolic functions. For this purpose, we exploited the carbohydrate-specific nutritional phenotypes of W6G or Sa5Y (Fig. 3C) to select transformants of these strains which could grow on (GlcN)2 or mannose, respectively. As for the antibiotic resistance transformation experiments described above, each strain was propagated as a biofilm on a crab shell fragment. Then, DNA from VCXB21 was added, and transformants were selected by using a medium that contains (GlcN)2 or mannose as the carbon source. After selection, transformants of W6G or Sa5Y were tested individually and confirmed to have stably acquired the new metabolic trait by growth on medium containing (GlcN)2 or mannose, respectively (Fig. 3D).

PCR assays were used to determine if acquisition of the new metabolic phenotypes by the W6G and Sa5Y transformants was correlated with acquisition of sequences for the corresponding genes. Each of the nine tested mannose-metabolizing transformants of Sa5Y was found to have acquired the VC0269-to-VC0270 locus, which encodes a mannose-6-phosphate isomerase, from the VCXB21 donor (Fig. 3E). These results also showed that the acquired VC0269-to-VC0270 locus from VCXB21 apparently replaced the intervening segment found between ORFs VC0268 and VC0271 in the Sa5Y recipient strain. Independent mapping showed that Sa5Y contains ∼9 kbp of DNA in place of VC0269 to VC0270 (data not shown). This region does not amplify under the conditions used in Fig. 3E. However, none of the tested mannose-utilizing transformants acquired the VC1820-to-VC1827 locus from the VCXB21 donor (data not shown), even though VC1827 is also predicted to encode a mannose-6-phosphate isomerase.

We also detected newly acquired DNA from the VCXB21 donor in the (GlcN)2-metabolizing transformants of W6G (Fig. 3F). A PCR assay that can detect both the parental W6G locus and the donor VCXB21 locus was used to test if nine independent (GlcN)2-utilizing transformants had acquired the VC1280-to-VC1286 gene cluster (Fig. 4). Each transformant generated a PCR product indicative of only the VCXB21 locus. These results show that the VC1280-to-VC1286 gene cluster of VCXB21 had been recombined into the W6G chromosome, between VC1279 and VC1287.

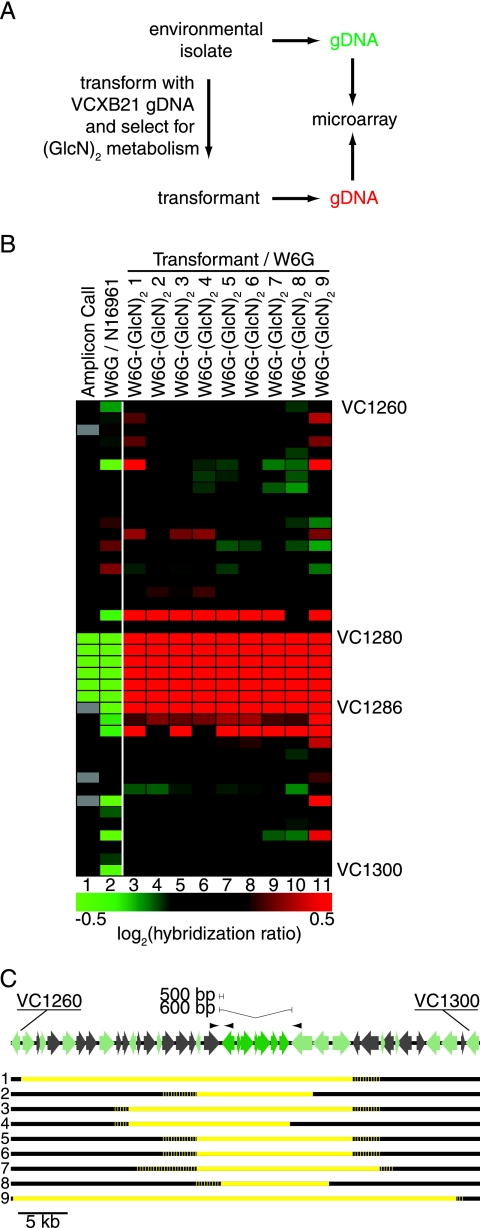

FIG. 4.

Recombination of large chromosome fragments at VC1260 to VC1300 by naturally competent V. cholerae. (A) Strategy for detecting transformed DNA by microarray hybridization. (B) Oligonucleotide microarray CGH comparison of W6G transformants selected for growth on (GlcN)2 to the original W6G isolate. Lane 1 is colored as in Fig. 3A and reflects processed calls, not raw hybridization data. Lane 2 is colored to reflect W6G (red) hybridization relative to N16961 (green). Lanes 3 to 11 reflect transformant hybridization (red) relative to that of environmental isolate W6G (green) as depicted in panel A. (C) Dark green ORFs (VC1280 to VC1286) are missing from W6G and were acquired by the transformants. Light green ORFs are present in W6G but can be distinguished from homologous genes in VCXB21 by virtue of reduced microarray hybridization and/or sequenced single-nucleotide polymorphisms. For each of nine transformants, yellow reflects DNA donated from VCXB21, and black reflects DNA of W6G origin. Recombination junctions were resolved to the gene. The dotted line reflects DNA of ambiguous origin due to a lack of sequenced single-nucleotide polymorphisms. The arrowheads above ORF map reflect primers used in Fig. 3F.

These results demonstrate that recently isolated environmental strains can acquire new metabolic traits from an antibiotic-resistant derivative of a clinical strain. To determine if these metabolic traits can be transferred between recently isolated environmental strains, we also transformed W6G cells with DNA from Sa5Y. We detected W6G transformants capable of metabolizing (GlcN)2 at transformation efficiencies comparable to those obtained with VCXB21 donor DNA (data not shown). However, when W6G served as the donor and Sa5Y as the recipient, we did not detect mannose-metabolizing Sa5Y transformants. This finding is readily explained by the PCR results depicted in Fig. 3F, showing that the VC0269 locus of VCXB21 was acquired in nine tested mannose-utilizing transformants of Sa5Y. Thus, failure to isolate mannose-utilizing transformants of Sa5Y is most likely due to the absence of VC0269 in W6G donor DNA (Fig. 3A) and suggests that VC1820 to VC1827 is transformed at low frequency or that its acquisition by Sa5Y does not confer a mannose-utilizing phenotype.

Transformants acquire large DNA fragments from the donor.

We performed CGH assays using oligonucleotide microarrays with probes for each of the annotated ORFs in V. cholerae N16961 to map the recombination events which generated the (GlcN)2-metabolizing W6G transformants (Fig. 4A). Sequencing demonstrated that the W6G genome has polymorphisms relative to N16961 at each of the ORFs (Fig. 4C). By combining the hybridization results with sequencing at sites flanking the apparent recombination site, we mapped the junction of transformed DNA with the parental chromosome to within a few kilobase pairs (Fig. 4C; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Remarkably, we observed the recombination of quite large DNA fragments. The mean size of the recombined fragment was 22.7 kbp, ranging from 7.9 to 44.9 kbp. This indicates that while recombination at sites immediately flanking the insertion/deletion at VC1280 to VC1286 is possible, it is more likely to happen further from the selected locus. Fragments of DNA substantially larger than the 5.6-kbp region that differs between W6G and VCXB21 recombine freely. Additionally, even at this relatively low resolution, it is clear that eight of the nine transformants underwent different recombination events, since only two transformants shared the same pair of junctions.

DISCUSSION

In this study we examined the genomic content of V. cholerae isolates from coastal sites in central California, a region that is geographically remote from areas where human epidemic strains occur (50). We identified sets of genes that are present in all, some, or none of the California isolates. Genes which vary among California isolates encode a range of functions, including some which determine differential metabolic capabilities; generally, they occur in small clusters and are not associated with genes predicted to confer DNA mobility. Two such clusters and their encoded functions were mobilized to strains lacking them via chitin-induced natural competence at transformation frequencies comparable to those observed with laboratory strains. Remarkably, these genes were acquired from the donor genome on segments of DNA as large as 40 kb. These large fragments have the potential to mediate the exchange of complex metabolic pathways, allowing sampling of many permutations of genes drawn from the pool of sequences in the V. cholerae pan-genome.

Previous studies using CGH to explore the genomes of V. cholerae isolates (8, 9) focused on a limited number of strains with the ability to cause disease in humans or animal models. Here, we have examined a larger number of environmental isolates from a geographically limited, but ecologically diverse, region. This set of isolates is optimal for characterizing the genomic and functional diversity of V. cholerae attributable to an association with different aquatic niches and diverse enough to allow identification of variably present genes with readily selectable phenotypes. Because many of these encode metabolic and sensing functions, their presence in a particular strain might determine its capacity to occupy a specific niche within an aquatic habitat. This is consistent with studies showing that geographic area, habitat, and ecological parameters, such as salinity and water temperature, influence V. cholerae population structure and dynamics (22, 23, 61). Keymer et al. (27) correlate the presence of several of the genes that vary between California isolates with environmental parameters measured during isolation, suggesting that genome content specializes isolates for different aquatic niches. An alternative, nonexclusive hypothesis is that the correlation with environmental parameters reflects common ancestry of isolates collected from waters with similar environmental parameters.

The microarray employed in this study could only detect genes present in sequenced strain N16961. Consequently, we could not monitor genes which are absent from N16961, including any which might be limited to aquatic or California V. cholerae. Two observations suggest that this set of genes is likely to be large. The draft genome of RC385, a V. cholerae strain which was repeatedly isolated from the Chesapeake Bay (TIGR Vibrio Genome Project, http://msc.tigr.org/vibrio/) encodes over 300 proteins (∼9.3% of the 3,221 predicted ORFs) with no BLASTp hit in the N16961 predicted proteome with an E value of less than 1e-10 (data not shown). In addition, results from suppressive subtractive hybridization performed with two V. cholerae isolates from southern California coastal sites were used to estimate that 3 to 20% of sequence in these genomes lack homology to N16961 (43). In both of these cases, the set of genes present in aquatic V. cholerae but absent from N16961 includes many genes that are annotated as hypothetical; others are predicted to have functions in cell surface modification, metabolism, and DNA mobility. These same types of functions are overrepresented in the variable gene set of our California isolates.

Despite this limitation, our analysis identified at least two classes of genes which are missing from or vary between the V. cholerae strains used in this study. The first class includes genes mobilized by dedicated mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer, such as phage and integrases. These include the well-described cholera toxin phage as well as an island containing VSP-II (8), which also encodes phage-like proteins. These are completely missing from the California isolates described here, and thus, are likely to have been recently acquired by epidemic V. cholerae lineages from non-V. cholerae sources. The second class of genes shows variability within the California isolates; most of these are not associated with known mobility elements or other clear markers of horizontal gene transfer. The interisolate variability observed for genes outside of the known mobile elements is likely to have arisen by more than one mechanism. Rapid gene loss through deletion plays a major role in bacterial genome evolution (38), and so a substantial portion of variability may be due to gene loss. In some cases, the variable genes may be on horizontally acquired mobile elements without clear signatures of horizontal gene transfer.

In addition to transduction (24) and conjugation (17), we expect natural transformation, which ordinarily incorporates acquired sequences by homologous recombination, to play an important role in the movement of genes in the variable gene set between different V. cholerae genomes. This prediction is supported by our observation that chitin-induced natural transformation allows California isolates long separated from clinical strains to take up and incorporate DNA from VCXB21, which was derived from an O1 El Tor Bangladeshi isolate. This result also shows that there is no significant physiological or sequence barrier to recombination between distant V. cholerae lineages. Taken together, the CGH data and results from the transformation experiments suggest the great diversity of genome content in these California isolates could have been generated by intraspecific recombination. This in turn may have been the consequence of natural transformation.

Perhaps the most notable of our findings is the capacity of V. cholerae isolates to take up and recombine chromosomal fragments over 40 kbp in length. The average recombined fragment length of 22.7 kbp in the W6G transformants is substantially longer than averages reported for Bacillus subtilis (7). Fragments of this size could encode complex metabolic and biosynthetic pathways. This is exemplified by the capacity of W6G, a California coastal isolate, to acquire DNA sufficient to encode components of the (GlcN)2 utilization pathway both from Sa5Y, another California isolate, and from an O1 El Tor strain. Since (GlcN)2-containing chitin polymers occur in natural chitin sources (39), these W6G transformants might be more fit than the parent strain to occupy aquatic habitats where chitin is available as a nutrient.

Neisseria spp. are naturally competent and contain variable genome segments that appear to have moved among Neisseria strains via transformation (48). These minimal mobile elements (MMEs) are short segments of one to five genes and are defined by their presence at homologous locations in multiple Neisseria species, by a mosaic structure, and, by a lack of obvious mechanism for horizontal transfer. Many of the V. cholerae genes in the variable set defined in this study fall in clusters that resemble MMEs; the best characterized example is the locus between VC0268 and VC0271. In strain N16961, this locus contains VC0269 to VC0270, two genes which were readily transferred to environmental isolate Sa5Y. By contrast, in Sa5Y, this region contains 9 kbp of DNA apparently not present in N16961. It remains to be seen whether genes in the V. cholerae variable gene set originated from or can be mobilized to other Vibrio species.

DNA taken up during chitin-dependent natural competence has several potential fates. Here we have demonstrated homologous recombination into the chromosome. If DNA taken up during competence includes the appropriate sequence elements, then the integron integrase (35) and transposases (59) encoded in the V. cholerae genome would be expected to use it as a substrate for site-specific recombination into the genome. No doubt, these recombinational processes would compete with nucleases that degrade DNA to nucleotides that can be used for DNA replication or further metabolism (51).

The approach used here has several important limitations. As noted above, the microarray we used for CGH contained probes only for the N16961 genome. Consequently, we could not monitor the distribution of genes absent from this clinical isolate. Since these genes would be expected to play a significant role in the adaptation of these isolates to their niches, their distribution among California isolates (and the functions that they encode) is of great interest. Likewise, probes for genes in the large, highly variable integron are underrepresented on the microarray, and so this particularly interesting part of the genome is poorly sampled. Due to these biases, the isolate collection may be even more diverse than is apparent. By probing more of the pan-genome, we would expect the set of conserved genes to remain largely unchanged (27) but the set of variable genes, which are to date largely unidentified, to increase dramatically. Finally, we focused our transformation analysis on large, multigene segments of DNA to establish the potential of this mechanism to contribute to the variability observed by CGH. However, the frequency of these events in the wild is unknown and might be substantially lower than the recombination of subgenic segments or of sequences located at sites without large insertion/deletions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chen-Yen Wu for technical support, TIGR for draft sequence data, and Alfred Spormann and Alex Nielsen for useful comments on the manuscript.

Funding was provided by the Ellison Foundation (to G.K.S.), the NIH (to G.K.S.), the Giannini Family Foundation (to M.C.M.), and the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford (to D.P.K., A.B.B., and G.K.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansaruzzaman, M., M. J. Albert, I. Kuhn, S. M. Faruque, A. K. Siddique, and R. Mollby. 1996. Differentiation of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates with biochemical fingerprinting and comparison with ribotyping. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 14:248-254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1997. Short protocols in molecular biology. Wiley, New York, NY.

- 3.Beltran, P., G. Delgado, A. Navarro, F. Trujillo, R. K. Selander, and A. Cravioto. 1999. Genetic diversity and population structure of Vibrio cholerae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:581-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bik, E. M., R. D. Gouw, and F. R. Mooi. 1996. DNA fingerprinting of Vibrio cholerae strains with a novel insertion sequence element: a tool to identify epidemic strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1453-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byun, R., L. D. H. Elbourne, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1999. Evolutionary relationships of pathogenic clones of Vibrio cholerae by sequence analysis of four housekeeping genes. Infect. Immun. 67:1116-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings, C. A., M. M. Brinig, P. W. Lepp, S. van de Pas, and D. A. Relman. 2004. Bordetella species are distinguished by patterns of substantial gene loss and host adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 186:1484-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubnau, D., and C. Cirigliano. 1972. Fate of transforming deoxyribonucleic acid after uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis: size and distribution of the integrated donor segments. J. Bacteriol. 111:488-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dziejman, M., E. Balon, D. Boyd, C. M. Fraser, J. F. Heidelberg, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae: genes that correlate with cholera endemic and pandemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziejman, M., D. Serruto, V. C. Tam, D. Sturtevant, P. Diraphat, S. M. Faruque, M. H. Rahman, J. F. Heidelberg, J. Decker, L. Li, K. T. Montgomery, G. Grills, R. Kucherlapati, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2005. Genomic characterization of non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae reveals genes for a type III secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3465-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falush, D., C. Kraft, N. S. Taylor, P. Correa, J. G. Fox, M. Achtman, and S. Suerbaum. 2001. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15056-15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farfan, M., D. Minana, M. C. Fuste, and J. G. Loren. 2000. Genetic relationships between clinical and environmental Vibrio cholerae isolates based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Microbiology 146:2613-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faruque, S. M., N. Chowdhury, M. Kamruzzaman, M. Dziejman, M. H. Rahman, D. A. Sack, G. B. Nair, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2004. Genetic diversity and virulence potential of environmental Vibrio cholerae population in a cholera-endemic area. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2123-2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Vallve, S., E. Guzman, M. A. Montero, and A. Romeu. 2003. HGT-DB: a database of putative horizontally transferred genes in prokaryotic complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:187-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardies, S. C., A. M. Comeau, P. Serwer, and C. A. Suttle. 2003. The complete sequence of marine bacteriophage VpV262 infecting Vibrio parahaemolyticus indicates that an ancestral component of a T7 viral supergroup is widespread in the marine environment. Virology 310:359-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochhut, B., J. Marrero, and M. K. Waldor. 2000. Mobilization of plasmids and chromosomal DNA mediated by the SXT element, a constin found in Vibrio cholerae O139. J. Bacteriol. 182:2043-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huq, A., E. B. Small, P. A. West, M. I. Huq, R. Rahman, and R. R. Colwell. 1983. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:275-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam, M. S., B. S. Drasar, and D. J. Bradley. 1990. Long-term persistence of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae 01 in the mucilaginous sheath of a blue-green alga, Anabaena variabilis. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:133-139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jermyn, W. S., and E. F. Boyd. 2002. Characterization of a novel Vibrio pathogenicity island (VPI-2) encoding neuraminidase (nanH) among toxigenic Vibrio cholerae isolates. Microbiology 148:3681-3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jermyn, W. S., and E. F. Boyd. 2005. Molecular evolution of Vibrio pathogenicity island-2 (VPI-2): mosaic structure among Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus natural isolates. Microbiology 151:311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang, S. C., and W. Fu. 2001. Seasonal abundance and distribution of Vibrio cholerae in coastal waters quantified by a 16S-23S intergenic spacer probe. Microb. Ecol. 42:540-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, S. C., V. Louis, N. Choopun, A. Sharma, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2000. Genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae in Chesapeake Bay determined by amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:140-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, S. C., and J. H. Paul. 1998. Gene transfer by transduction in the marine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2780-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaper, J. B., H. Lockman, M. M. Baldini, and M. M. Levine. 1984. Recombinant nontoxinogenic Vibrio cholerae strains as attenuated cholera vaccine candidates. Nature 308:655-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaolis, D. K., J. A. Johnson, C. C. Bailey, E. C. Boedeker, J. B. Kaper, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3134-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keymer, D. P., M. C. Miller, G. K. Schoolnik, and A. B. Boehm. 2007. Genomic and phenotypic diversity of coastal Vibrio cholerae strains is linked to environmental factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3705-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, C. C., E. A. Joyce, K. Chan, and S. Falkow. 2002. Improved analytical methods for microarray-based genome-composition analysis. Genome Biol. 3:RESEARCH0065. http://genomebiology.com/2006/7/9/R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kotetishvili, M., O. C. Stine, Y. Chen, A. Kreger, A. Sulakvelidze, S. Sozhamannan, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing has better discriminatory ability for typing Vibrio cholerae than does pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and provides a measure of phylogenetic relatedness. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2191-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, M., T. Shimada, J. G. Morris, Jr., A. Sulakvelidze, and S. Sozhamannan. 2002. Evidence for the emergence of non-O1 and non-O139 Vibrio cholerae strains with pathogenic potential by exchange of O-antigen biosynthesis regions. Infect. Immun. 70:2441-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, X., and S. Roseman. 2004. The chitinolytic cascade in Vibrios is regulated by chitin oligosaccharides and a two-component chitin catabolic sensor/kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:627-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linz, B., M. Schenker, P. Zhu, and M. Achtman. 2000. Frequent interspecific genetic exchange between commensal Neisseriae and Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1049-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipp, E. K., A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2002. Effects of global climate on infectious disease: the cholera model. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:757-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobitz, B., L. Beck, A. Huq, B. Wood, G. Fuchs, A. S. Faruque, and R. Colwell. 2000. Climate and infectious disease: use of remote sensing for detection of Vibrio cholerae by indirect measurement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1438-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazel, D., B. Dychinco, V. A. Webb, and J. Davies. 1998. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science 280:605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meibom, K. L., M. Blokesch, N. A. Dolganov, C. Y. Wu, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2005. Chitin induces natural competence in Vibrio cholerae. Science 310:1824-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meibom, K. L., X. B. Li, A. T. Nielsen, C. Y. Wu, S. Roseman, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2524-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mira, A., H. Ochman, and N. A. Moran. 2001. Deletional bias and the evolution of bacterial genomes. Trends Genet. 17:589-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muzzarelli, R. A. A. 1973. Natural chelating polymers: alginic acid, chitin, and chitosan, vol. 55. Pergamon Press, New York, NY.

- 40.Nair, G. B., B. L. Sarkar, S. P. De, M. K. Chakrabarti, R. K. Bhadra, and S. C. Pal. 1988. Ecology of Vibrio cholerae in the freshwater environs of Calcutta, India. Microb. Ecol. 15:203-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neate, E. V., A. M. Greenhalgh, D. A. McPhee, and S. M. Crowe. 1992. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide mediates the loss of CD4 from the surface of purified peripheral blood monocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 90:539-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Shea, Y. A., F. J. Reen, A. M. Quirke, and E. F. Boyd. 2004. Evolutionary genetic analysis of the emergence of epidemic Vibrio cholerae isolates on the basis of comparative nucleotide sequence analysis and multilocus virulence gene profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4657-4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purdy, A., F. Rohwer, R. Edwards, F. Azam, and D. H. Bartlett. 2005. A glimpse into the expanded genome content of Vibrio cholerae through identification of genes present in environmental strains. J. Bacteriol. 187:2992-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quirke, A. M., F. J. Reen, M. J. Claesson, and E. F. Boyd. 2006. Genomic island identification in Vibrio vulnificus reveals significant genome plasticity in this human pathogen. Bioinformatics 22:905-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddacliff, G. L., M. Hornitzky, J. Carson, R. Petersen, and R. Zelski. 1993. Mortalities of goldfish, Carassius auratus (L), associated with Vibrio cholerae (non-01) infection. J. Fish Dis. 16:517-520. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reen, F. J., E. F. Boyd, S. Porwollik, B. P. Murphy, D. Gilroy, S. Fanning, and M. McClelland. 2005. Genomic comparisons of Salmonella enterica serovar Dublin, Agona, and Typhimurium strains recently isolated from milk filters and bovine samples from Ireland, using a Salmonella microarray. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1616-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato, N., and S. Ehira. 2003. GenoMap, a circular genome data viewer. Bioinformatics 19:1583-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders, N. J., and L. A. Snyder. 2002. The minimal mobile element. Microbiology 148:3756-3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snel, B., P. Bork, and M. A. Huynen. 2002. Genomes in flux: the evolution of archaeal and proteobacterial gene content. Genome Res. 12:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinberg, E. B., K. D. Greene, C. A. Bopp, D. N. Cameron, J. G. Wells, and E. D. Mintz. 2001. Cholera in the United States, 1995-2000: trends at the end of the twentieth century. J. Infect. Dis. 184:799-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart, G. J., and C. A. Carlson. 1986. The biology of natural transformation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 40:211-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stine, O. C., S. Sozhamannan, Q. Gou, S. Zheng, J. G. Morris, Jr., and J. A. Johnson. 2000. Phylogeny of Vibrio cholerae based on recA sequence. Infect. Immun. 68:7180-7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, C. Donati, D. Medini, N. L. Ward, S. V. Angiuoli, J. Crabtree, A. L. Jones, A. S. Durkin, R. T. Deboy, T. M. Davidsen, M. Mora, M. Scarselli, I. Margarit y Ros, J. D. Peterson, C. R. Hauser, J. P. Sundaram, W. C. Nelson, R. Madupu, L. M. Brinkac, R. J. Dodson, M. J. Rosovitz, S. A. Sullivan, S. C. Daugherty, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, M. L. Gwinn, L. Zhou, N. Zafar, H. Khouri, D. Radune, G. Dimitrov, K. Watkins, K. J. O'Connor, S. Smith, T. R. Utterback, O. White, C. E. Rubens, G. Grandi, L. C. Madoff, D. L. Kasper, J. L. Telford, M. R. Wessels, R. Rappuoli, and C. M. Fraser. 2005. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:13950-13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson, J. R., S. Pacocha, C. Pharino, V. Klepac-Ceraj, D. E. Hunt, J. Benoit, R. Sarma-Rupavtarm, D. L. Distel, and M. F. Polz. 2005. Genotypic diversity within a natural coastal bacterioplankton population. Science 307:1311-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsirigos, A., and I. Rigoutsos. 2005. A sensitive, support-vector-machine method for the detection of horizontal gene transfers in viral, archaeal and bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:3699-3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vimont, S., S. Dumontier, V. Escuyer, and P. Berche. 1997. The rfaD locus: a region of rearrangement in Vibrio cholerae O139. Gene 185:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waldor, M. K., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waldor, M. K., H. Tschape, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. A new type of conjugative transposon encodes resistance to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and streptomycin in Vibrio cholerae O139. J. Bacteriol. 178:4157-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1998. Role of rpoS in stress survival and virulence of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 180:773-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zo, Y. G., I. N. Rivera, E. Russek-Cohen, M. S. Islam, A. K. Siddique, M. Yunus, R. B. Sack, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2002. Genomic profiles of clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae O1 in cholera-endemic areas of Bangladesh. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12409-12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.