Abstract

Despite the fact that rice paddy fields (RPFs) are contributing 10 to 25% of global methane emissions, the organisms responsible for methane production in RPFs have remained uncultivated and thus uncharacterized. Here we report the isolation of a methanogen (strain SANAE) belonging to an abundant and ubiquitous group of methanogens called rice cluster I (RC-I) previously identified as an ecologically important microbial component via culture-independent analyses. To enrich the RC-I methanogens from rice paddy samples, we attempted to mimic the in situ conditions of RC-I on the basis of the idea that methanogens in such ecosystems should thrive by receiving low concentrations of substrate (H2) continuously provided by heterotrophic H2-producing bacteria. For this purpose, we developed a coculture method using an indirect substrate (propionate) in defined medium and a propionate-oxidizing, H2-producing syntroph, Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans, as the H2 supplier. By doing so, we significantly enriched the RC-I methanogens and eventually obtained a methanogen within the RC-I group in pure culture. This is the first report on the isolation of a methanogen within RC-I.

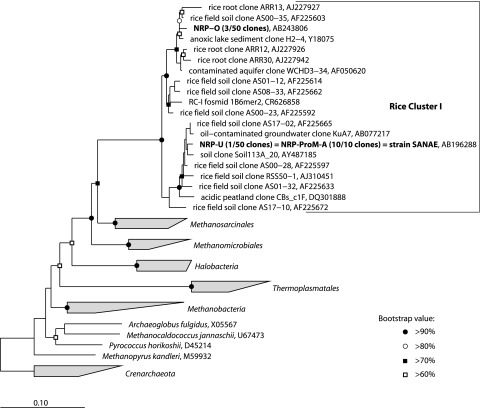

Since their discovery in an Italian rice paddy field (RPF) in 1998 (12), the uncultivated microorganisms in the group RC-I (rice cluster I) have been a focus of attention with regard to potential ecological and biogeochemical importance. To date, the following aspects of RC-I have been elucidated. (i) Cultivation-independent molecular studies combined with stable isotope analysis strongly suggested that members of the RC-I group are most active and play a key role in methane production from RPFs (22). (ii) The members are highly likely to be H2-utilizing methanogens because abundant populations of RC-I Archaea were observed in enrichment cultures with H2 (8, 25, 33) and a metagenomic approach showed that an RC-I methanogen had a full set of genes involved in methanogenesis from H2-CO2 (9). (iii) The group was found to be a major archaeal component in natural RPFs regardless of geographical locations and seasonal changes, accounting for 20 to 50% of total methanogenic populations (20, 28, 39). (iv) In addition to the occurrence in RPFs, they have also been observed in a wide variety of anoxic environments, such as peatland (1, 33), sediment of freshwater lakes (40), and contaminated aquifer (7, 37), indicating the widespread habitat of RC-I on our planet. Given the molecular ecological results and biogeochemical data on paddy fields (6, 27), the RC-I group has been recognized as one of the most important yet-to-be isolated, and thus uncharacterized, methanogens that may significantly impact the global methane cycle. For these reasons, we set out to isolate a pure culture of an RC-I group methanogen with the hope that its characterization might contribute to the understanding of these important methane sources. Here we report the isolation and initial characterization of such a microbe.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Environmental samples, microorganisms, and cultivation.

Rice paddy soils were obtained from four places near Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Methanogenic sludge was collected from a methanogenic municipal sewage treatment plant at Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Strain SANAE was isolated in this study as a novel hydrogenotrophic methanogenic archaeon. Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans strain MPOB (DSM 10017) was purchased from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). All cultivations were carried out at 37°C with 50-ml serum vials containing 20 ml of an artificial medium (31) under an atmosphere of N2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol]) without shaking. The purity of strain SANAE was checked by 16S rRNA gene-based clone analysis with the universal archaeal primer pair Ar109f-1490R (16, 38), terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism based on a method reported by Chin et al. (2), FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) with 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for the isolates (see the FISH section below), evaluation by a failure to recover bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplification by PCR with the universal bacterial primer pair EUB338*-1490R (14, 38), and cultivation with the following media at 37 and 55°C: (i) thioglycolate medium (Difco) containing ca. 150 kPa H2-CO2 (in the headspace) and 10 mM sulfate; (ii) thioglycolate medium containing 20 mM lactate and 10 mM sulfate; (iii) thioglycolate medium containing 10 mM sucrose, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM cellobiose, and 10 mM xylose; and (iv) AC medium (Difco).

Analysis of 16S rRNA genes.

DNA extraction from environmental samples and enrichment cultures and PCR amplification were performed as described previously (16). PCR amplification was done with the archaeal universal primer pair Ar109f-1490R (16, 38). PCR products were purified with a MinElute purification kit (QIAGEN). Clone libraries were constructed with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences of isolated strains were amplified with the archaeal primer pair Arch21F-1490R (5, 38). Sequences were determined with a CEQ DTC kit-quick start kit (Beckman Coulter) and a CEQ2000XL (Beckman Coulter) automated DNA sequencer. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with the ARB program (24). The base phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method implemented in the ARB program with nearly full-length (>1,000 nucleotides) sequences. Partial-length sequences (<1,000 nucleotides) were inserted into the base tree with the parsimony insertion tool of the ARB program to show their approximate positions. Bootstrap resampling analysis (11) for 1,000 replicates was performed with the PAUP* 4.0 package (36) to estimate the confidence of tree topologies.

FISH.

Fixation of cells and whole-cell in situ hybridization were performed as described previously (32). The 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe SANAE1136 (5′-GTGTACTCGCCCTCCTCG-3′) for strain SANAE was designed with the PROBE DESIGN tool of the ARB program (24). The probe was labeled with Cy3. The stringency of hybridization was adjusted by adding formamide to the hybridization buffer (25% [vol/vol] for SANAE1136).

Microscopy and chemical analyses.

An Olympus fluorescence microscope was used for studies of cell morphology and epifluorescence (Olympus BX50F). Short-chain fatty acids, methane, H2, and carbon dioxide were measured as described previously (15-17).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequence data obtained in this study were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers AB162774, AB196288, AB236108, and AB243792 to AB243811.

RESULTS

Attempt to cultivate RC-I methanogens with hydrogen (H2).

First, to choose the appropriate inoculum to cultivate RC-I methanogens, we began with a survey of four RPF soils via 16S rRNA gene-based clone analysis with archaeon-specific PCR primers. Fifty clones were randomly picked from each clone library. While molecular signals of the RC-I group methanogens have been detected from all RPF samples, we selected a sample from Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, Japan, which had the highest clonal frequency of RC-I phylotypes (Fig. 1, phylotypes NRP-O [3/50 clones] and NRP-U [1/50 clones]). On the basis of the assumption that RC-I probably is a group of hydrogenotrophic methanogens, as indicated by previous studies, the first enrichment trial involved anaerobic incubation of the soil sample with H2 (ca. 150 kPa) as an energy source in both liquid and solid media at 37°C. Many methanogens grew in the enrichment cultures after 3 days of incubation, as judged by the methane production with cell growth and F420 autofluorescence (data not shown). However, further analysis of these cells via 16S rRNA gene-based cloning analysis showed that not all of the archaeal clones belonged to the RC-I group but some were closely related to previously isolated methanogens such as Methanobacterium bryantii (sequence similarity, 98%; sequence accession no. AB236108).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among the clones obtained in this study, strain SANAE, and RC-I environmental clones inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide changes per sequence position. The symbols at nodes show bootstrap values obtained after 1,000 resamplings. Accession numbers are also shown after each reference sequence.

Cultivation of an RC-I methanogen by the coculture method.

Our first attempt, described above, was based on a canonical method for cultivation, resulting in the isolation of a nontargeted H2-utilizing methanogen. One of the conceivable reasons was the difference between in vitro and in situ physicochemical conditions. In particular, we assumed that a high concentration of H2 in the headspace (for example, 100 kPa) might be fatal because it was approximately 1,000- to 10,000-fold higher than the in situ H2 concentrations of natural RPFs (4, 10). Most likely, this cultivation condition was not suitable for RC-I members to compete with the growth of previously isolated methanogens. In fact, it is well known that high concentrations of substrates sometimes allow minor in situ but fast-growing in vitro microbes to grow.

If the in vitro condition is similar to the in situ RC-I habitat, would it be possible to cultivate the targeted microbes in the artificial culture medium? Indeed, some of previously uncultured microbes have been isolated in pure cultures only when the substrate was provided at low concentrations close to the natural environment (3, 19, 29). The underlying idea was that RC-I methanogens in RPFs might thrive by receiving low concentrations of substrate (H2) continuously provided by heterotrophic H2-producing bacteria (this way of living is commonly referred to as interspecies H2 transfer) (18, 30). We thus established a coculture method by using the syntrophic propionate-oxidizing H2-producing bacterium Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans (13) as the supplier of H2. Bacteria like S. fumaroxidans are called syntrophs and are fermentative bacteria that catalyze the oxidation of a variety of substrates (fatty acids, alcohols, and aromatic compounds) via reactions that are thermodynamically unfavorable unless H2 is continuously removed (18, 30). Thus, they typically live in syntrophy with H2-consuming microbes such as methanogens. Therefore, if cultivation is done together with a particular syntroph growing on a substrate that the syntroph can preferably metabolize, it can continuously provide low concentrations of H2 to methanogens (ca. 10 to 30 Pa in the case of propionate) (17, 21, 34, 35). Thus, for the next challenge, we cultured the soil samples with an anaerobic propionate-oxidizing syntroph, S. fumaroxidans, as the H2 supplier. Since the doubling growth time of S. fumaroxidans is ca. 5 days (13), as a result, hydrogen, an end product of its metabolism, will be provided to methanogens at a slow rate.

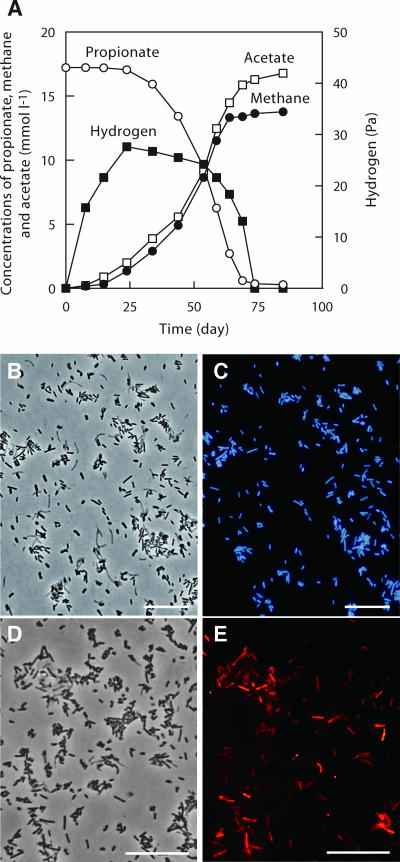

A primary enrichment culture was made from the rice paddy soil with propionate (20 mM) as the sole energy source and the pregrown cells of an S. fumaroxidans culture. After 3 months of incubation of the coculture enrichment with S. fumaroxidans, cell growth, propionate degradation, and methane production were observed (Fig. 2A). The culture was successively transferred to fresh medium every 50 to 80 days (5 to 10% [vol/vol] inoculum). During cultivation, the partial pressure of H2 in the cultures was kept at less than 30 Pa (Fig. 2A). Microscopic observation after five transfers showed that the community consisted simply of F420-autofluorescent methanogen-like cells and Syntrophobacter-like, oval, rod-shaped cells. To identify the methanogens thriving in the syntrophic culture, we constructed an rRNA gene clone library with an archaeal universal primer set. The clone analysis indicated that all 10 of the archaeal sequences examined were affiliated with a single phylotype within the RC-I group (Fig. 1, phylotype NRP-ProM-A). To confirm whether the clonal sequence obtained from the dominant archaeal population in the culture, a specific DNA probe (SANAE1136) was designed and applied to the culture. As a result, the syntrophic culture actually contained SANAE1136 probe-positive rods (Fig. 2D and E). These observations indicated that the microbe possessing the rRNA gene detected as phylotype NRP-ProM-A was the dominant archaeal population in the culture.

FIG. 2.

RC-I methanogens in coculture with syntrophic, propionate-oxidizing bacteria. (A) Stoichiometric conversion of propionate in the enrichment culture containing methanogenic cells of the RC-I group. (B and C) Photomicrographs of the enrichment culture after five transfers obtained by phase-contrast (B) and fluorescence (C) microscopy indicating the presence of F420-autofluorescent methanogens in identical fields. (D and E) FISH of RC-I cells. Phase-contrast (D) and fluorescence (E) images of RC-I cells stained with Cy3-labeled 16S rRNA probe SANAE1136. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

Isolation of the RC-I methanogen in pure culture.

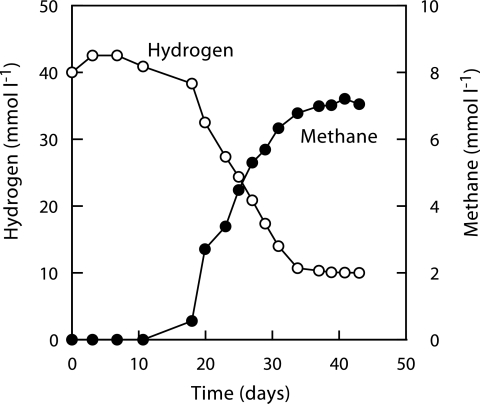

To obtain the RC-I methanogen in pure culture from the coculture enrichment, we used the serial-dilution method with both liquid and solid media and different substrates that are generally utilized by H2-utilizing methanogens, such as H2 (ca. 150 kPa) and formate (40 mM), with the propionate coculture system as the inoculum. In the H2 cultures, we observed the growth of the RC-I methanogen that converted H2 to methane stoichiometrically, which is explained by an equation 4H2 + CO2 → CH4 + 2H2O (Fig. 3). The growth rate, however, was found to be very slow compared with those of previously characterized methanogens; i.e., the doubling time of RC-I cells with H2 was 4.2 days (based on the optical density at 600 nm), indicating that isolation requires a long time. After using the serial-dilution methods for over a year, we eventually succeeded in isolating the RC-I methanogen in a pure culture, designated strain SANAE (Fig. 4), by the deep-agar method with H2 as the substrate.

FIG. 3.

Methane production from H2 by strain SANAE at 37°C.

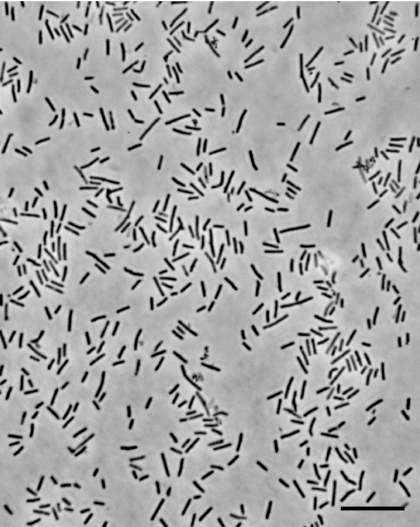

FIG. 4.

Phase-contrast micrograph of strain SANAE cells grown on H2 (ca. 150 kPa) supplemented with acetate (1 mM) and yeast extract (0.01%). Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Strain SANAE had nonmotile, rod-shaped cells. They were 1.8 to 2.4 μm long and 0.3 to 0.6 μm wide. The strain formed brownish, lens-shaped colonies 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter in deep agar with H2 (ca. 150 kPa in the headspace). In addition to H2, the isolate can also grow with formate (40 mM). Acetate was not utilized as an energy source.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a new way to isolate methanogens, by using syntrophs that can supply H2 at very low concentrations (coculture method). As expected, the RC-I methanogen could be cultivated by the coculture method whereas conventional enrichments from the same environmental samples with high levels of H2 yielded fast-growing methanogens such as Methanobacterium spp. Assuming that strain SANAE is representative of the members of the RC-I group, our results suggest that the RC-I group has a higher affinity for H2 than other, fast-growing, members and thus may be well adapted to the low-H2 habitat of RPFs. This speculation was also suggested by two reports on stable-isotope-probing analysis (23, 26). Lu et al. reported that Methanobacteriales and Methanosarcinales incorporated 13C when rice root was incubated in a high-H2 atmosphere in the presence of 13CO2, while 13C was preferentially incorporated into RC-I under an N2 atmosphere in which a low concentration of H2 was produced by fermentative bacteria from rice root materials (23). According to the stable-isotope-probing analysis with 13C-labeled propionate for RPF soil reported by Lueders et al., 13C was incorporated not only into rRNA of syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria but also into certain methanogenic archaeal groups, including RC-I (26). These results imply that RC-I methanogens probably live syntrophically with propionate-oxidizing bacteria in RPF environments. Consequently, given that the members of RC-I may have a high affinity for H2 and live in syntrophy with fermentative bacteria such as syntrophic propionate oxidizers, it can be said that our coculture method is a suitable way to cultivate RC-I methanogens.

Very recently, a complete metagenomic sequence of an RC-I member was reported (9). The sequence was retrieved from a paddy sample incubated at 50°C, indicating that the organism is most likely a thermophilic methanogen. Since the temperature of natural RPFs is normally not stable, it is reasonable that a variety of sequences within the RC-I cluster, which may represent either mesophilic or thermophilic members, have been detected from RPFs. That metagenomic study revealed that the thermophile has a unique set of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase. Considering that RPFs receive a seasonal change in redox potential (oxic to anoxic), these unique genes may be indispensable for survival in such an environment.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity between the metagenome and strain SANAE is, however, only 92.0% (Fig. 1, RC-I fosmid 1B6mer2), indicating that the two organisms are phylogenetically distinct at the genus level. Therefore, further studies cross-linking both the metagenomic information of thermophilic RC-I and our mesophilic isolate SANAE are needed to better understand how RC-I methanogens contribute to global methane emission from RPF environments. There are several important questions that have to be addressed to fully understand the role of RC-I methanogens. (i) Can thermophilic RC-I methanogens also grow slowly with a low concentration of H2? (ii) What is the biochemical or physiological background of the low maximum specific growth rate and the assumed high affinity for hydrogen of RC-I and similar organisms? (iii) What is the difference in enzymatic characteristics, in particular, antioxidant enzymes, between the two different RC-I methanogens? To address these questions, we are now performing further biochemical (including examination of affinity for H2 in terms of Km) and genomic analyses of our isolate. We are also trying to isolate the thermophilic RC-I methanogen whose genomic sequence is complete.

Since the coculture method can mimic the natural ecosystem, where H2 is provided at low concentrations, the method was supposed to have potential for the cultivation of uncharacterized methanogens residing in other ecosystems. To prove this, we also applied the cultivation technique to a methanogenic digester that contains a relatively large amount of uncultured archaeal members within the order Methanomicrobiales. By strategy described above, we successfully isolated a new methanogen, designated strain NOBI-1 (16S rRNA gene sequence accession no. AB162774), which was one of the predominant methanogens in the original ecosystem but was not cultivated so far at the genus or family level. In this case, all of the primary enrichment cultures using a high partial pressure of H2 with the same inoculum resulted in the cultivation of well-known methanogens like those of the genus Methanobacterium. Detailed information about the enrichment, isolation, and physiological properties of the isolate will be reported in the near future. These findings strongly indicate that the coculture method should work for isolation of fastidious but ecologically important methanogens that would otherwise escape conventional isolation strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fumio Inagaki at JAMSTEC and Kenneth H. Nealson at the University of Southern California for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was financially supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization, and the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka. S.S. was supported by the Research Fellowship of the JSPS for Young Scientists (04663).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basiliko, N., J. B. Yavitt, P. M. Dees, and S. M. Merkel. 2003. Methane biogeochemistry and methanogen communities in two northern peatland ecosystems, New York State. Geomicrobiol. J. 20:563-577. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin, K.-J., T. Lukow, S. Stubner, and R. Conrad. 1999. Structure and function of the methanogenic archaeal community in stable cellulose-degrading enrichment cultures at two different temperature (15 and 30°C). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 30:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connon, S. A., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. High-throughput methods for culturing microorganisms in very-low-nutrient media yield diverse new marine isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3878-3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conrad, R., H. Schütz, and M. Babbel. 1987. Temperature limitation of hydrogen turnover and methanogenesis in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:281-289. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLong, E. F. 1992. Archaea in coastal marine environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5685-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dentener, F., R. Derwent, E. Dlugokencky, E. Holland, I. Isaksen, J. Katima, V. Kirchhoff, P. Matson, P. Midgley, and M. Wang. 2001. Climate change 2001, the scientific basis. Third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 7.Dojka, M. A., P. Hugenholtz, S. K. Haack, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Microbial diversity in a hydrocarbon- and chlorinated-solvent-contaminated aquifer undergoing intrinsic bioremediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3869-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erkel, C., D. Kemnitz, M. Kube, P. Ricke, K.-J. Chin, S. Dedysh, R. Reinhardt, R. Conrad, and W. Liesack. 2005. Retrieval of first genome data for rice cluster I methanogens by a combination of cultivation and molecular techniques. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 53:187-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erkel, C., M. Kube, R. Reinhardt, and W. Liesack. 2006. Genome of Rice Cluster I Archaea—the key methane producers in the rice rhizosphere. Science 313:370-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fey, A., and R. Conrad. 2000. Effect of temperature on carbon and electron flow and on the archaeal community in methanogenic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4790-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ficker, M., K. Krastel, S. Orlicky, and E. Edwards. 1999. Molecular characterization of a toluene-degrading methanogenic consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5576-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groβkopf, R., S. Stubner, and W. Liesack. 1998. Novel euryarchaeotal lineages detected on rice roots and in the anoxic bulk soil of flooded rice microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4983-4989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmsen, H. J. M., B. L. M. Van Kuijk, C. M. Plugge, A. D. L. Akkermans, W. M. De Vos, and A. J. M. Stams. 1998. Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans sp. nov., a syntrophic propionate-degrading sulfate-reducing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1383-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatamoto, M., H. Imachi, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 2007. Identification and cultivation of anaerobic, syntrophic long-chain fatty acid degrading microbes from mesophilic and thermophilic methanogenic sludges. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1332-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imachi, H., Y. Sekiguchi, Y. Kamagata, S. Hanada, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 2002. Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum gen. nov. sp. nov., an anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1729-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imachi, H., Y. Sekiguchi, Y. Kamagata, A. Loy, Y.-L. Qiu, P. Hugenholtz, N. Kimura, M. Wagner, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 2006. Non-sulfate-reducing, syntrophic bacteria affiliated with Desulfotomaculum cluster I are widely distributed in methanogenic environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2080-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imachi, H., Y. Sekiguchi, Y. Kamagata, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 2000. Cultivation and in situ detection of a thermophilic bacterium capable of oxidizing propionate in syntrophic association with hydrogenotrophic methanogens in a thermophilic methanogenic granular sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3608-3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson, B. E., and M. J. McInerney. 2002. Anaerobic microbial metabolism can proceed close to thermodynamic limits. Nature 415:454-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaeberlein, T., K. Lewis, and S. S. Epstein. 2002. Isolating “uncultivable” microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment. Science 296:1127-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krüger, M., P. Frenzel, D. Kemnitz, and R. Conrad. 2005. Activity, structure and dynamics of the methanogenic archaeal community in a flooded Italian rice field. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 51:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krylova, N., P. H. Janssen, and R. Conrad. 1997. Turnover of propionate in methanogenic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 23:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, Y., and R. Conrad. 2005. In situ stable isotope probing of methanogenic Archaea in the rice rhizosphere. Science 309:1088-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, Y.-H., T. Lueders, M. W. Friedrich, and R. Conrad. 2005. Detecting active methanogenic populations on rice roots using stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 7:326-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Förster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. König, T. Liss, R. Lüβmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lueders, T., K.-J. Chin, R. Conrad, and M. W. Friedrich. 2001. Molecular analyses of methyl-coenzyme M reductase α-subunit (mcrA) genes in rice field soil and enrichment cultures reveal the methanogenic phenotype of a novel archaeal lineage. Environ. Microbiol. 3:194-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lueders, T., B. Pommerenke, and M. W. Friedrich. 2004. Stable-isotope probing of microorganisms thriving at thermodynamic limits: syntrophic propionate oxidation in flooded soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5778-5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neue, H.-U. 1993. Methane emission from rice fields. BioScience 43:466-473. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishnan, B., T. Lueders, P. F. Dunfield, R. Conrad, and M. W. Friedrich. 2001. Archaeal community structures in rice soils from different geographical regions before and after initiation of methane production. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:175-186. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rappé, M. S., S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 418:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schink, B. 1997. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:262-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekiguchi, Y., Y. Kamagata, K. Nakamura, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 2000. Syntrophothermus lipocalidus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, syntrophic, fatty-acid-oxidizing anaerobe which utilizes isobutyrate. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:771-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekiguchi, Y., Y. Kamagata, K. Syutubo, A. Ohashi, H. Harada, and K. Nakamura. 1998. Phylogenetic diversity of mesophilic and thermophilic granular sludges determined by 16S rRNA gene analysis. Microbiology 144:2655-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sizova, M. V., N. S. Panikov, T. P. Tourova, and P. W. Flanagan. 2003. Isolation and characterization of oligotrophic acido-tolerant methanogenic consortia from a Sphagnum peat bog. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:301-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stams, A. J. M. 1994. Metabolic interactions between anaerobic bacteria in methanogenic environments. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 66:271-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stams, A. J. M., K. C. F. Grolle, C. T. M. J. Frijters, and J. B. van Lier. 1992. Enrichment of thermophilic propionate-oxidizing bacteria in syntrophy with Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum or Methanobacterium thermoformicicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:346-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swofford, D. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 37.Watanabe, K., Y. Kodama, and N. Kaku. 2002. Diversity and abundance of bacteria in an underground oil-storage cavity. BMC Microbiol. 2:23-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisburg, W. G., S. M. Barns, D. A. Pelletier, and D. J. Lane. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, X.-L., M. W. Friedrich, and R. Conrad. 2006. Diversity and ubiquity of thermophilic methanogenic archaea in temperate anoxic soils. Environ. Microbiol. 8:394-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zepp Falz, K., C. Holliger, R. Groβkopf, W. Liesack, A. N. Nozhevnikova, B. Müller, B. Wehrli, and D. Hahn. 1999. Vertical distribution of methanogens in the anoxic sediment of Rotsee (Switzerland). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2402-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]