Abstract

In observing Francisella tularensis interactions with nonphagocytic cell lines in vitro, we noted significant adherence, invasion, and intracellular growth of the bacteria within these cells. F. tularensis live vaccine strain invasion of nonprofessional phagocytic cells is inhibited by cytochalasin D and nocodazole, suggesting that both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons are important for invasion.

Francisella tularensis is a highly virulent intracellular bacterial pathogen that causes tularemia in a wide variety of hosts (46). While infection is primarily transmitted through the bite of an infected arthropod or by contact with infected animal material, the capacity of this organism to cause pneumonic infection at a very low dose led to its weaponization by several nations and classification by the CDC as a category A select agent (47). While many laboratories have studied the interaction of F. tularensis with phagocytes, little is known about the interactions of this bacterium with nonphagocytic cells. However, in murine experiments, F. tularensis LVS has been observed within hepatocytes (11, 30), alveolar type II cells (14), and, potentially, early hepatic lesions (39). Other work has found that F. tularensis is protected from gentamicin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (16) and HepG2 cells (38). In this work, we aimed to quantitate and visualize the invasion of several types of nonphagocytic cells by F. tularensis LVS to begin to characterize the cellular mechanisms by which these interactions occur in vitro.

One research group has recently observed structures resembling type IV pili on the surface of LVS (20). In order to ascertain whether F. tularensis LVS is adherent to cells, cell association assays were performed with HEp-2 cells, human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells, and A549 tissue culture cells. F. tularensis LVS was grown in modified Mueller-Hinton broth (3) supplemented with 150 mM NaCl to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.3 to 0.5, added to minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at a multiplicity of infection of ∼100, and centrifuged at 600 × g to facilitate interactions with cells. After 1 h, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the monolayer was solubilized with PBS containing 1% saponin before being plated. This treatment did not affect the viability of LVS when plated on modified Mueller-Hinton agar with 0.5% sheep blood (data not shown). Adherence levels of F. tularensis LVS were 0.9% ± 0.04% for HEp-2 cells, 0.5% ± 0.01% for HBE cells, and 0.5% ± 0.08% for A549 cells. The mean CFU recovered per well for each cell type was statistically significantly different from the level of recovery of bacteria that were added to wells without tissue culture cells and treated with gentamicin (P < 0.001).

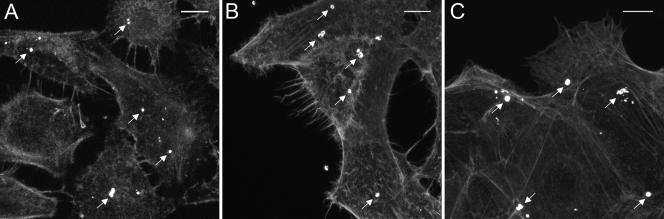

To more fully characterize F. tularensis adherence, we performed bacterial adherence assays and examined the interactions between LVS and cells using confocal microscopy. Bacteria, labeled with Francisella antiserum (BD Biosciences) and detected by Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Invitrogen) binding, were routinely observed attached to the surfaces of HEp-2, HBE, or A549 cells (Fig. 1). These bacteria appeared to bind specifically to the surfaces of the cells; very few organisms bound to the glass coverslip. These observations provide complementing evidence that the quantitative adherence assay is measuring bacterial attachment to tissue culture cells and not to the tissue culture plate. Additionally, the numbers of bacteria that were attached to the tissue culture cells were consistent with results obtained using the quantitative adherence assay (0.5% to 0.9% adherence is equivalent to 0.5 to 0.9 bacteria per cell).

FIG. 1.

Confocal microscopy of F. tularesis LVS adherence to A549 (A), HEp-2 (B), and HBE cells (C). Images were taken 1 h postinfection and are z projections of stacks of images. F. tularensis LVS (white) was detected with rabbit Francisella tularensis antiserum and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488; F-actin was stained with rhodamine phalloidin (gray). The white arrows in each panel indicate some of the adherent bacteria present on each cell type. Bars, 10 μm.

While examining the 1-h adherence assays, it became apparent that some bacteria were located within the tissue culture cells. Preliminary observations did not detect visible actin rearrangements as a part of the host cell interactions, in contrast to the interactions that occur with bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella and Shigella spp. and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. In order to quantitatively assess the level at which F. tularensis is able to invade tissue culture cells, we adapted a gentamicin protection assay that is used to study Francisella bacterium-macrophage interactions and that has been used by us and others to study Salmonella invasion (22, 25, 29, 38). After allowing bacteria to interact with the cell monolayers for 4 h, treating them with 10 μg/ml gentamicin for 1 h, and then washing and lysing them as described above, ∼5 × 103 to ∼5 × 104 CFU were consistently recovered from each of the three cell types, representing 0.05% to 0.1% of the inoculum. As a control, we confirmed that treatment of F. tularensis LVS with gentamicin in the absence of eukaryotic cells sterilized the well to the limit of detection (<20 CFU/ml). F. tularensis entry (i.e., gentamicin protection) steadily increased in each of the cell types up to 4 h postinoculation (data not shown). Time points beyond 4 h were not useful since intracellular growth of the internalized bacteria obscured the data (8). Due to these results, we used 4-hour incubation times in our standard assays.

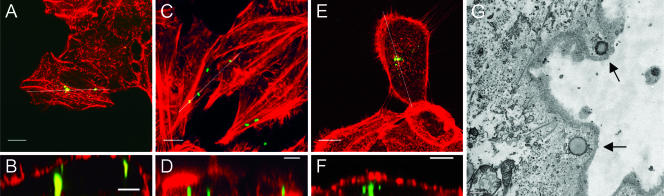

To confirm the results of the quantitative invasion assay, we examined F. tularensis interactions with tissue culture cell lines by using confocal microscopy. Coverslips were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS, and labeled as described above. Cellular actin was visualized with rhodamine phalloidin according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). A primary goal of these experiments was to confirm that the organisms were located physically within the host cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, C, and E, bacteria are clearly associated with the tissue culture cells, with virtually no organisms adhering to the glass slide. Using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), we could demonstrate that the cell-associated bacteria were intracellular because vertical digital slices (Fig. 2B, D, and F) of the areas indicated in Fig. 2A, C, and E demonstrate that the bacteria are surrounded by actin-associated membranes. Virtually the same results were obtained for each of the tissue culture cell lines tested (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Confocal and transmission electron microscopy of F. tularensis entry into A549 cells (A, B), HEp-2 cells (C, D), and HBE nonphagocytic tissue culture cells (E, F, G). (A, C, and E) Z-projections of stacks of images of a 4-h invasion assay showing bacteria (green) that are located beneath the membrane of the infected nonphagocytic cells. White lines indicate areas showing that bacteria are surrounded by actin-associated membranes. (B, D, and F) Selected slices through the z projections stacks along the indicated lines. Bacteria are immunolabeled green with primary rabbit Francisella tularensis antiserum and secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488. Cellular F-actin is stained red with rhodamine phalloidin. (G) Transmission electron microscopy of HBE cells infected with the virulent F. tularensis strain 1547-57 for 1 h. Arrows indicate the internalized bacteria. Experiments performed with LVS detected similar internalization events (data not shown). Bars, 10 μm (A, C, E), 5 μm (B, D, F), and 500 nm (G).

In order to preliminarily determine what cellular mechanisms might be required for the internalization of F. tularensis LVS, HEp-2 tissue culture cells were treated with either 2 μg/ml cytochalasin D to inhibit actin filament polymerization or 10 μg/ml nocodazole to inhibit microtubule polymerization from 30 min prior to infection, and 1-h invasion assays were performed. The treatment of HEp-2 cells with cytochalasin D almost completely abrogated the entry of bacteria into HEp-2 cells (2.4% ± 3.1% of wild-type entry). The treatment of cells with nocodazole reduced the invasion of HEp-2 cells by LVS to 26.9% ± 12.6% of that of untreated cells. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was included as a control for the efficacy of cytoskeletal disruption since Salmonella invasion requires actin polymerization (17, 19, 21, 26). As expected, serovar Typhimurium invasion was reduced to 1.4% ± 0.1% by treatment with cytochalasin D, but nocodazole treatment did not significantly reduce the invasion of HEp-2 cells by Salmonella. These data indicate that both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons are important for the invasion of HEp-2 cells by LVS. We extended our characterization of F. tularensis entry into epithelial cells by incubating virulent F. tularensis subsp. holarctica strain 1547-57 or F. tularensis LVS with HBE cells and examining the interactions by transmission electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2G, two organisms were observed inside of an HBE cell, apparently having just entered the cells. It is unclear whether the intracellular organisms were confined within a vacuolar membrane or whether they had escaped into the cell cytoplasm. Virtually the same results were obtained when infecting HBE cells with F. tularensis LVS (data not shown).

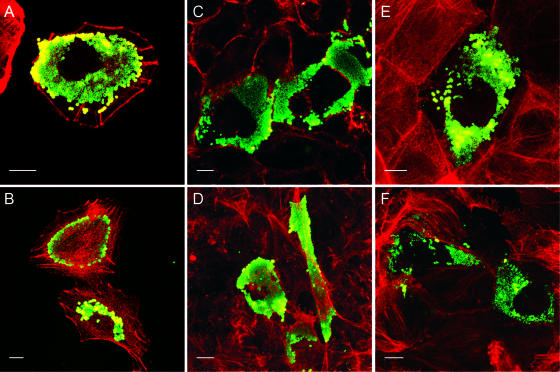

To determine whether the invasion of tissue culture cells by F. tularensis LVS was followed by significant bacterial replication, samples were examined by confocal microscopy at 8 h and 24 h postinfection. At 8 h postinfection, groups of dividing bacteria were observed within tissue culture cells (data not shown). At 24 h postinfection, significant bacterial growth was observed in each of the three tissue culture cell types (Fig. 3). In the majority of instances, the bacterial growth was clumped together as microcolonies within the cytoplasmic space of the cell. At 24 h, these microcolonies typically surrounded the nucleus of the cell, which was apparent by the cellular space that lacked significant bacterial growth. Occasionally, the intracellular bacteria displayed unusual immunostaining patterns, although this was not consistently observed (Fig. 3B). In some instances, lysed eukaryotic cells with visible gaps in their cortical actin staining were observed with bacteria apparently exiting the cell (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Confocal microscopy of F. tularesis LVS growth within A549 (A, B), HEp-2 (C, D), or HBE (E, F) cells. Bacteria have replicated extensively within the cytoplasm of each infected cell; the nuclei of infected cells appear to exclude LVS replication. The images are z projections of stacks of images and were taken 25 h postinfection. Bacteria are immunolabeled green with rabbit Francisella tularensis antiserum and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488, and cellular F-actin is stained red with rhodamine phalloidin. Bars, 10 μm.

To quantify the growth within the cells, intracellular growth curve experiments were performed with HEp-2, HBE, and A549 cells. Wells were infected and treated as for the invasion assays described above, but after 1 h, gentamicin was removed and fresh medium was added. Cells were lysed with PBS and 1% saponin at appropriate time points. Viable-cell counts of well lysates showed that the bacteria began to multiply at 5 h postinfection and continued to grow at a steady rate up to the 25-h time point. Within this 20-h time period, the bacterial load increased ∼1,000-fold in each of the three tissue culture cell types (growth differences between cell lines were not statistically significant). The rate of growth was comparable to that of the organisms in optimized modified Mueller-Hinton broth and was similar to that observed in macrophage studies. After 24 h in tissue culture, some cells could be seen detached from the surface, although the cell monolayer remained largely intact. These data demonstrate that F. tularensis LVS is capable of invading and replicating within nonphagocytic tissue culture cells, indicating that entry into and growth within nonphagocytic cells during Francisella infection may contribute to pathogenesis and disease progression.

In this work, we have presented an initial characterization of the ability of F. tularensis LVS to adhere to and invade nonphagocytic cells. It is well established that the virulence of F. tularensis depends upon the ability to grow within host cells. These bacteria can enter macrophages, from various hosts, via CR3 receptor (7, 9, 10), mannose receptor (4, 44), or scavenger receptor A (36) and replicate (1, 2, 15, 18, 32, 34, 42, 45). Studies of interactions between host macrophages and F. tularensis have identified genes (i.e., mglA, iglA, iglB, iglC, iglD, pdpA to -D, and acpA) that are involved in modifying the macrophage intracellular environment to permit intracellular replication (2, 5, 6, 27, 28, 33, 35, 40-43). The molecular details of these modifications are not well understood, but the Francisella intracellular compartment is clearly different from a typical phagolysosome (31, 42, 43).

The work described here contributes to the emerging picture of F. tularensis pathogenesis and is consistent with the findings of others (11, 14). Entry into nonphagocytic cells is typically an active process for the microorganism since the cells typically lack innate uptake mechanisms for large particles. Our observations that F. tularensis efficiently adheres to, enters, and replicates within nonphagocytic hepatocytes and alveolar type II epithelial cell lines provide additional evidence that the interactions of F. tularensis with nonphagocytic cells may play an important role in its virulence strategy. Work is under way in our group to identify the factors involved in entry and to characterize the mechanism of action.

Another aspect of this work is that the development of this tissue culture model will allow comparisons of the intracellular growth mechanisms of F. tularensis within phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. While it is likely that growth mechanisms in phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells will overlap significantly, it is also possible that F. tularensis will interact uniquely with each cell type due to differences in entry and/or differences in the signals received from different cells. Identification and characterization of the virulence factors required in each intracellular environment would further elucidate the unique requirements for survival of intracellular bacterial pathogens like F. tularensis in host cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lee-Ann Allen for the generous gift of rabbit F. tularensis antiserum and for helpful discussions and review of data. We thank Ramona McCaffrey and Grant Schulert for helpful insights and discussions concerning this work. We also gratefully acknowledge the expertise and assistance of the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Facility and Carver College of Medicine BSL3 Laboratories.

S.R.L. was supported by a U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Graduate Fellowship and performed this research while on appointment as a DHS Fellow under the DHS Scholarship and Fellowship Program, a program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) for DHS through an interagency agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities under DOE contract number DE-AC05-06OR23100.

All opinions expressed in this paper are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of DHS, DOE, or ORISE.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, L. A. 2003. Mechanisms of pathogenesis: evasion of killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Microbes Infect. 5:1329-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony, L. S. D., R. D. Burke, and F. E. Nano. 1991. Growth of Francisella spp. in rodent macrophages. Infect. Immun. 59:3291-3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, C. N., D. G. Hollis, and C. Thornsberry. 1985. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Francisella tularensis with a modified Mueller-Hinton broth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:212-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balagopal, A., A. S. MacFarlane, N. Mohapatra, S. Soni, J. S. Gunn, and L. S. Schlesinger. 2006. Characterization of the receptor-ligand pathways important for entry and survival of Francisella tularensis in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 74:5114-5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron, G. S., and F. E. Nano. 1998. MglA and MglB are required for the intramacrophage growth of Francisella novicida. Mol. Microbiol. 29:247-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron, G. S., T. J. Reilly, and F. E. Nano. 1999. The respiratory burst-inhibiting acid phosphatase AcpA is not essential for the intramacrophage growth or virulence of Francisella novicida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolger, C. E., C. A. Forestal, J. K. Italo, J. L. Benach, and M. B. Furie. 2005. The live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis replicates in human and murine macrophages but induces only the human cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Checroun, C., T. D. Wehrly, E. R. Fischer, S. F. Hayes, and J. Celli. 2006. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:14578-14583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens, D. L., B.-Y. Lee, and M. A. Horwitz. 2005. Francisella tularensis enters macrophages via a novel process involving pseudopod loops. Infect. Immun. 73:5892-5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens, D. L., B.-Y. Lee, and M. A. Horwitz. 2004. Virulent and avirulent strains of Francisella tularensis prevent acidification and maturation of their phagosomes and escape into the cytoplasm in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 72:3204-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlan, J. W., and R. J. North. 1992. Early pathogenesis of infection in the liver with the facultative intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Salmonella typhimurium involves lysis of infected hepatocytes by leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 60:5164-5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reference deleted.

- 13.Reference deleted.

- 14.Craven, R., J. Hall, J. Fuller, and T. Kawula. 2006. Francisella tularensis interactions with alveolar type II epithelial cells, abstr. 6C. Abstr. Fifth Int. Conf. Tularemia.

- 15.Evans, M. E., D. W. Gregory, W. Schaffner, and Z. A. McGee. 1985. Tularemia: a 30-year experience with 88 cases. Medicine 64:251-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forestal, C. A., J. L. Benach, C. Carbonara, J. K. Italo, T. J. Lisinski, and M. B. Furie. 2003. Francisella tularensis selectively induces proinflammatory changes in endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 171:2563-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis, C. L., T. A. Ryan, B. D. Jones, S. J. Smith, and S. Falkow. 1993. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature 364:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis, E. 1925. Tularemia. JAMA 84:1243-1250. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galán, J. E., C. Ginocchio, and P. Costeas. 1992. Molecular and functional characterization of the Salmonella invasion gene invA: homology of InvA to members of a new protein family. J. Bacteriol. 174:4338-4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil, H., J. L. Benach, and D. G. Thanassi. 2004. Presence of pili on the surface of Francisella tularensis. Infect. Immun. 72:3042-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginocchio, C., J. Pace, and J. E. Galan. 1992. Identification and molecular characterization of a Salmonella typhimurium gene involved in triggering the internalization of salmonellae into cultured epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5976-5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golovliov, I., M. Ericsson, G. Sandström, A. Tärnvik, and A. Sjöstedt. 1997. Identification of proteins of Francisella tularensis induced during growth in macrophages and cloning of the gene encoding a prominently induced 23-kilodalton protein. Infect. Immun. 65:2183-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reference deleted.

- 24.Reference deleted.

- 25.Jones, B. D., C. A. Lee, and S. Falkow. 1992. Invasion by Salmonella typhimurium is affected by the direction of flagellar rotation. Infect. Immun. 60:2475-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones, B. D., H. F. Paterson, A. Hall, and S. Falkow. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium induces membrane ruffling by a growth factor-receptor-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:10390-10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauriano, C. M., J. R. Barker, F. E. Nano, B. P. Arulanandam, and K. E. Klose. 2003. Allelic exchange in Francisella tularensis using PCR products. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauriano, C. M., J. R. Barker, S. S. Yoon, F. E. Nano, B. P. Arulanandam, D. J. Hassett, and K. E. Klose. 2004. MglA regulates transcription of virulence factors necessary for Francisella tularensis intraamoebae and intramacrophage survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4246-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindgren, H., I. Golovliov, V. Baranov, R. K. Ernst, M. Telepnev, and A. Sjostedt. 2004. Factors affecting the escape of Francisella tularensis from the phagolysosome. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:953-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malkova, D., K. Blazek, V. Danielova, J. Holubova, M. Lavickova, Z. Marhoul, and J. Schramlova. 1986. Some diagnostic, biologic and morphologic characteristics of Francisella tularensis strains isolated from the ticks Ixodes ricinus (L.) in the Prague agglomeration. Folia Parasitol. (Prague) 33:87-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCaffrey, R. L., and L. A. Allen. 2006. Francisella tularensis LVS evades killing by human neutrophils via inhibition of the respiratory burst and phagosome escape. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80:1224-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLendon, M. K., M. A. Apicella, and L. A. Allen. 2006. Francisella tularensis: taxonomy, genetics, and immunopathogenesis of a potential agent of biowarfare. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:167-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohapatra, N. P., A. Balagopal, S. Soni, L. S. Schlesinger, and J. S. Gunn. 2006. AcpA is a Francisella acid phosphatase that affects intramacrophage survival and virulence. Infect. Immun. 75:390-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morner, T. 1992. The ecology of tularaemia. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 11:1123-1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nano, F. E., N. Zhang, S. C. Cowley, K. E. Klose, K. K. Cheung, M. J. Roberts, J. S. Ludu, G. W. Letendre, A. I. Meierovics, G. Stephens, and K. L. Elkins. 2004. A Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island required for intramacrophage growth. J. Bacteriol. 186:6430-6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierini, L. M. 2006. Uptake of serum-opsonized Francisella tularensis by macrophages can be mediated by class A scavenger receptors. Cell Microbiol. 8:1361-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reference deleted.

- 38.Qin, A., and B. J. Mann. 2006. Identification of transposon insertion mutants of Francisella tularensis tularensis strain Schu S4 deficient in intracellular replication in the hepatic cell line HepG2. BMC Microbiol. 6:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen, J. W., J. Cello, H. Gil, C. A. Forestal, M. B. Furie, D. G. Thanassi, and J. L. Benach. 2006. Mac-1+ cells are the predominant subset in the early hepatic lesions of mice infected with Francisella tularensis. Infect. Immun. 74:6590-6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reilly, T. J., G. S. Baron, F. E. Nano, and M. S. Kuhlenschmidt. 1996. Characterization and sequencing of a respiratory burst-inhibiting acid phosphatase from Francisella tularensis. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10973-10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reilly, T. J., R. L. Felts, M. T. Henzl, M. J. Calcutt, and J. J. Tanner. 2006. Characterization of recombinant Francisella tularensis acid phosphatase A. Protein Expr. Purif. 45:132-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santic, M., M. Molmeret, K. E. Klose, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2006. Francisella tularensis travels a novel, twisted road within macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 14:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santic, M., M. Molmeret, K. E. Klose, S. Jones, and Y. A. Kwaik. 2005. The Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island protein IglC and its regulator MglA are essential for modulating phagosome biogenesis and subsequent bacterial escape into the cytoplasm. Cell Microbiol. 7:969-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulert, G. S., and L. A. Allen. 2006. Differential infection of mononuclear phagocytes by Francisella tularensis: role of the macrophage mannose receptor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80:563-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sjöstedt, A. 2006. Intracellular survival mechanisms of Francisella tularensis, a stealth pathogen. Microbes Infect. 8:561-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarnvik, A., and L. Berglund. 2003. Tularemia. Eur. Respir. J. 21:361-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, T. H., J. A. Hutt, K. A. Garrison, L. S. Berliba, Y. Zhou, and C. R. Lyons. 2005. Intranasal vaccination induces protective immunity against intranasal infection with virulent Francisella tularensis biovar A. Infect. Immun. 73:2644-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]