Abstract

In recent years, there has been considerable interest in using the oral commensal gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus gordonii as a live vaccine vector. The present study investigated the role of d-alanylation of lipoteichoic acid (LTA) in the interaction of S. gordonii with the host innate and adaptive immune responses. A mutant strain defective in d-alanylation was generated by inactivation of the dltA gene in a recombinant strain of S. gordonii (PM14) expressing a fragment of the S1 subunit of pertussis toxin. The mutant strain was found to be more susceptible to killing by polymyxin B, nisin, magainin II, and human β defensins than the parent strain. When it was examined for binding to murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs), the dltA mutant exhibited 200- to 400-fold less binding than the parent but similar levels of binding were shown for Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) knockout DCs and HEp-2 cells. In a mouse oral colonization study, the mutant showed a colonization ability similar to that of the parent and was not able to induce a significant immune response. The mutant induced significantly less interleukin 12p70 (IL-12p70) and IL-10 than the parent from DCs. LTA purified from the bacteria induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-6 production from wild-type DCs but not from TLR2 knockout DCs, and the mutant LTA induced a significantly smaller amount of these two cytokines. These results show that d-alanylation of LTA in S. gordonii plays a role in the interaction with the host immune system by contributing to the relative resistance to host defense peptides and by modulating cytokine production by DCs.

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is an amphiphilic polymer of polyphosphoglycerol or polyphosphoribitol, anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane by a glycolipid. Each phosphoglycerol or phosphoribitol on this molecule may be modified with glycosylation or, more often, may contain d-alanine (10, 11). The dlt operon, which contains four genes, dltA, dltB, dltC, and dltD, is responsible for the d-alanylation of teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid. The dltA gene encodes the d-alanyl carrier protein ligase which activates the d-alanine for ligation to the d-alanyl carrier protein (DltC). Disruption of any one of the dlt genes will eliminate d-alanylation (30). d-Alanylation confers a positive charge to the LTA and has been demonstrated to have a role in the regulation of autolytic activity (12) as well as a role in binding Mg2+ which is essential for the activation of Mg2+-dependent membrane enzymes (2).

A number of studies have demonstrated that d-alanylation in Streptococcus agalactiae, Staphylococcus aureus, and group A Streptococcus spp. plays a role in escaping host defense peptides (HDP) (19, 32, 33, 41). HDP are recognized as one of the critical components of the innate immune system. These amphipathic peptides target and exert antimicrobial activity on cells with a negatively charged surface by disrupting transmembrane potential and lipid symmetry, which results in cell lysis (13). Studies have also shown that the lack of d-alanylation leads to increased susceptibility to phagocytic cells (5, 33), decreased adherence to macrophages (1), loss of ability to colonize cotton rat nares (41), and increased susceptibility to neutrophil killing (20). Since d-alanylation appears to have a role in the interaction of gram-positive bacteria with the host immune system, it would stand to reason that d-alanylation may have a role in modulating the immune response.

Streptococcus gordonii is a commensal gram-positive organism that naturally resides in the human oral mucosa. In recent years, this organism has been under study as a potential vector for live oral vaccines (23). S. gordonii is a favorable vaccine vector due to its nonpathogenic nature, early colonization of the oral cavity, persistence in colonization, and ability to express heterologous antigens on its surface. S. gordonii has recently been used in a phase I clinical trial to demonstrate that the organism can be safely administered to humans by the nasal/oral route and colonization can be quickly eliminated by antibiotic treatment (18). However, eliciting a strong immune response with recombinant S. gordonii has been difficult. In previous studies, the oral colonization of mice with recombinant S. gordonii PM14 surface expressing the S1 fragment of pertussis toxin elicited only a weak mucosal immune response (24). Since eliciting a strong immune response is critical to the use of S gordonii as an oral vector, it is important to understand how S. gordonii interacts with the components of the innate and adaptive immune systems and what role d-alanylation may play in that interaction. A previous study by Clemans et al. (4) created a dltA mutant from S. gordonii DL1 (Challis), but this group only explored the effects of the mutation on intragenic coaggregations.

In this study, we insertionally inactivated the dltA gene in S. gordonii to determine the role of d-alanylation in modulating immune responses. More specifically, we examined the role of S. gordonii lipoteichoic acid (LTA) d-alanylation in cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance, the interaction with dendritic cells (DCs), and the induction of cytokines from DCs. The interactions of S. gordonii with DCs are explored because these immune cells have an important role in dictating the subsequent adaptive immune response (25).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Streptococci were cultured in a brain heart infusion (BHI; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) broth at 37°C aerobically without shaking and on BHI agar or Todd-Hewitt agar (Becton Dickinson and Company) in candle jars. S. gordonii strains used for the MIC assays were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (Becton Dickinson and Company) supplemented with 3% (wt/vol) glucose. Antibiotics, when needed, were included in the media at 10 μg/ml erythromycin or 250 μg/ml kanamycin. Escherichia coli PK3330 was cultured aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (1% [wt/vol] Bio-tryptone, 1% [wt/vol] NaCl, and 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract) with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 300 μg/ml erythromycin.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant property | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. gordonii | ||

| DL1 | Wild type | D. LeBlanc |

| PM14 | DL1 harboring pPM14 | 27 |

| PM14 dltA | dltA mutant of PM14, gene insertionally inactivated with ermAM | This study |

| E. coli PK3330 | DH5α containing pDC11 | 4 |

| S. pyogenes | Type M22 | Claes Schalen, Lund University, Sweden |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDC11 | pBluescript KS(+) carrying the S. gordonii DL1 dltA gene interrupted with ermAM | 4 |

| pPM14 | xyl tet promoter expressing the S1 subunit of pertussis toxin, pDL276 backbone (13 kb), Kanr | 27 |

Insertional inactivation of the S. gordonii dltA gene with ermAM.

To inactivate the dltA gene in S. gordonii, the previously described pDC11 carrying the dltA::ermAM construct was used (4). pDC11 is a pBluescript derivative with a 1.4-kb BamHI-KpnI fragment of the S. gordonii DL1 dltA gene insertionally inactivated by ermAM (922 bp). The pDC11 plasmid was isolated from E. coli by using an alkaline lysis method (3). The plasmid was subsequently linearized using BamHI and used in the natural transformation of S. gordonii PM14 by using methods previously described (21). Transformants were selected on BHI agar containing kanamycin and erythromycin.

Genomic DNA was isolated from the transformants and used as templates for amplification of the interrupted dltA gene by PCR. A typical PCR consisted of 1 μl of a 1/100 dilution of S. gordonii genomic DNA, 50 pmol of each of the primers SL355 (CCGGATCCTGACCTCGCTGATTAAGCCC) and SL356 (GGGGGTACCTCTCCTGTCGTGGTCTATGGTGGGC), 2 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Burlington, ON) in a final reaction mixture volume of 100 μl. PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 30 s at 54°C, and 2.5 min at 72°C.

Isolation of LTA.

LTA was isolated from S. gordonii by using the hot phenol extraction method (32). Cells from a 500-ml overnight culture were harvested by centrifugation and washed in cold sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.7). Cells were resuspended in the same buffer and disrupted using glass beads in a cell disintegrator (Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co. Ltd., Gonshall, Surrey, United Kingdom) for 1 h at 4°C. The crude cell extract was recovered and centrifuged for 15 min at 300 × g. The supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of prewarmed 80% (wt/vol) aqueous phenol and stirred at 65°C for 1 h. The solution was cooled at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged for 30 min at 300 × g, and the aqueous layer was collected. An equal volume of sodium acetate buffer was then added to the phenol layer, stirred again at 65°C for 1 h, cooled, and centrifuged. Once again, the aqueous layer was collected. The two aqueous fractions were combined and dialyzed against 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). The LTA extracts were subsequently freeze-dried.

For the isolation of LTA to be used in dendritic cell stimulation assays, S. gordonii was grown in 500 ml of BHI prepared in endotoxin-free water (Invitrogen). The cells were disrupted as described above, and LTA was isolated by butanol extraction, followed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography on octyl-Sepharose as described by Morath et al. (29). In the isolation process, care was taken to prevent the introduction of endotoxin by ensuring reagents were prepared in endotoxin-free water and containers. The purified LTA was analyzed on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (42) and detected as a single band by the cationic dye Stains-All (Sigma-Aldrich) (22). The purified LTA was then freeze-dried.

Analysis of d-alanine and phosphorus contents.

The amounts of d-alanine in the LTA samples were determined using the method described by Peschel et al. (32). LTA samples (5 mg) were adjusted to a pH of 9 to 10 with NaOH to a final volume of 100 μl and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C to hydrolyze the d-alanine esters. Samples were then incubated for another hour at 37°C following the addition of 200 μl of 0.2 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.4) containing 8.5 U of amino acid oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., Oakville, ON) to convert d-alanine to pyruvate. Trichloroacetic acid (30%; 100 μl) was added to inactivate the oxidase enzyme. Finally, 100 μl of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (0.1% solution in 2 M HCl) was added to the solution and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 200 μl of 2.5 M NaOH and the absorbance at 525 nm was determined. A standard curve was constructed using d-alanine (Sigma-Aldrich).

The amount of phosphorus in the LTA samples was determined according to the method described by Zhou and Arthur (43). Briefly, the LTA samples (50 μg/μl) were boiled in 2 M HCl for 2.5 h. Ten microliters of 70% HClO4 was added to various amounts of the LTA samples, and distilled water was added to make a total volume of 200 μl. Finally, 1 ml of malachite green solution (3 volumes of 0.4% [wt/vol] malachite green in distilled water, 1 volume of 4.2% ammonium molybdate in 5 M HCl, 0.06% Tween 20) was added, and the solution was allowed to stand for 20 min before the absorbance at 660 nm (A660) was determined. A standard curve was constructed using K2PO4.

Alcian blue binding assay.

S. gordonii cells grown in BHI were harvested at mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.5) and were washed once by centrifugation (5 min at 10,000 × g) with 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (pH 7). The cells were resuspended in MOPS buffer to a final OD600 of 0.5, and the cationic dye Alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 65 μg/ml. Samples were rotated at 3 rpm at room temperature. After 10 min, the mixtures were centrifuged to pellet the bacteria. The unbound Alcian blue in the supernatant fluids was measured at 650 nm using a spectrophotometer. In parallel, tubes containing the same amount of Alcian blue in MOPS buffer but without bacteria were treated similarly, as controls. The amount of Alcian blue bound to the bacteria was calculated as (A530 of supernatant without bacteria − A530 of supernatant with bacteria)/A530 of supernatant without bacteria × 100.

MIC assays.

The MIC of polymyxin B sulfate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) was determined in 96-well polypropylene microplates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) by a microdilution method. Bacteria (50 μl; 107 CFU) were added to the wells, which contained 50 μl of twofold-diluted polymyxin B. The starting concentration for polymyxin B was 200 μg/ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and examined visually for bacterial growth. The lowest concentration that inhibited growth was considered to be the MIC.

Susceptibility to cationic antimicrobial peptides in kinetic inhibition assays.

These assays were performed in Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with glucose in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Bacteria (107 CFU in 100 μl) were added to tubes containing 100 μl of one concentration of polymyxin B sulfate, nisin, magainin II, human β defensins 1 and 2, or histatin 5, and these samples were incubated at 37°C. All peptides were used at a concentration of 200 μg/ml, with the exception of that of magainin II, which was 225 μg/ml. Survival over time was determined by plating on Todd-Hewitt agar in triplicate and counting the resulting colonies after incubation for 48 h. All peptides except for human β defensins 1 and 2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Human β defensins 1 and 2 were purchased from Peptides International Inc. (Louisville, KY).

DC culture.

Bone marrow-derived DCs were cultured, using the method described by Lutz et al. (26), from female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, St. Constant, PQ) or from female Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) knockout mice. Briefly, on day 0, femurs and tibia of the mice were flushed, and the resulting bone marrow suspension was passed through a 70- or 100-μm-pore-size cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Red blood cells were subsequently lysed using a hypotonic 0.2% (wt/vol) NaCl solution, and a hypertonic 1.6% (wt/vol) NaCl solution was added to restore equilibrium. The cells were then seeded at 0.2 million per ml of RPMI medium with l-glutamine (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2% HEPES, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0.003% β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 or 40 ng/ml of murine granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rGM-CSF; Peprotech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. On day 3, fresh RPMI medium containing rGM-CSF was added to double the original volume. On day 6, the nonadherent cells were harvested and used for subsequent experiments.

Cell binding assays.

An in vitro fluid-phase assay was used to investigate the binding between S. gordonii and murine DCs or HEp-2 cells. Mouse DCs were cultured as described above. HEp-2 cells (ATCC accession number CCL-23; Manassas, VA) were grown to a confluent monolayer, and cells were detached using HyQtase trypsin replacement (Sigma-Aldrich). To prevent phagocytosis by the DCs, all reagents were chilled to 4°C prior to use, and the incubation was performed at 4°C. Early exponential-phase S. gordonii cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS. The mammalian cells were also washed and resuspended in PBS. Cells and bacteria were mixed in a ratio of 1:50, using 1 million DCs or HEp-2 cells per sample, and rotated at 4 rpm. Samples were taken at 20, 30, and 45 min and centrifuged at 100 × g for 3 min. The pellet was washed once with BHI and resuspended in 50 μl of BHI. The pellet was sonicated for 5 seconds at an amplitude of 10 (Vibracell Sonics & Materials Inc., Danbury, CT) to lyse the mammalian cells but not the bacteria. The sample was then serially diluted and plated in triplicate on selective agar. All plates were then incubated for 48 h, and colonies were counted.

Mouse colonization study.

An animal trial with mice was conducted to determine if the S. gordonii dltA mutant could colonize the oral mucosa of mice and to determine the immune response to this recombinant bacterium. Five-week-old female BALB/c mice (n = 5) were given two consecutive intraoral/intranasal doses of 109 CFU of the parent or mutant S. gordonii on days 1 and 2, using methods described previously (24). Oral swabs were taken on days 3, 10, 17, and 24. Saliva was collected on day 27, and sera were collected by heart puncture when mice were euthanized on day 28. At the time of euthanasia, swabs of the oral cavity, pharynx, trachea, and nasal cavity were taken. Swabs were placed in 1 ml of ice-cold BHI broth and vortexed for 1 min. Bacterial counts for S. gordonii were determined by plating the broth on BHI containing antibiotics and for total aerobes and facultative anaerobes on sheep blood agar. Sample colonies from the BHI plates were regrown in BHI broth, and the proteins were extracted with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (17). Western immunoblotting was performed with these samples to confirm the identity of the streptococci recovered from the oral cavity. The blots showed that the protein samples from the swab colonies were expressing the SpaPS1 recombinant protein, which was recognized by anti-S1 monoclonal antibody A4 (data not shown).

The generation of specific antibody responses in mice against pertussis toxin or S. gordonii was evaluated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) as described previously (24). Microtiter plate wells were coated with 100 ng of pertussis toxin (Chiron Inc., Emeryville, CA) or S. gordonii PM14 fixed with 0.125% glutaraldehyde. Anti-pertussis toxin and anti-S. gordonii immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in sera were assayed with a starting dilution of 1/20. The IgG was detected with the alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1/7,500 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich). Anti-pertussis toxin and anti-S. gordonii IgA antibodies in saliva (1/20 dilution) were detected with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA antibody (1/20,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by avidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (1/20,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich).

DC stimulation.

An in vitro stimulation was used to investigate the induction of cytokines from DCs. Six-day-old mouse DCs were cultured as above and seeded at 1 × 106 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture plates. Late-exponential-phase wild-type cells, the dltA mutant, and S. pyogenes were grown in BHI. The medium was prepared with endotoxin-free water and sterilized through a 0.2 μM filter into endotoxin-free plastic conical tubes. The bacterial cultures were washed once with endotoxin-free, sterile PBS (Invitrogen) and added to DCs at three different ratios of bacteria to DCs (1:1, 2.5:1, and 5:1). DCs were also stimulated with purified LTA at the concentrations indicated. In all stimulation assays, DCs were stimulated with 1 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; E. coli; Sigma-Aldrich) or left unstimulated for 24 h as controls. Each treatment was replicated in duplicate or triplicate.

Cytokine ELISAs.

Cytokine concentrations in the DC culture supernatants were determined by ELISA using capture and detection antibodies and cytokine standards for mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-4, IL-12p70, IL-2 (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN), and IL-10 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Maxisorp Nunc plates were coated with 50 μl of 1 μg/ml capture antibody, and the undiluted supernatants or the cytokine standards were added to the wells. Biotinylated detection antibody (50 μl of 0.2 μg/ml) was used to detect each cytokine, and an ELISA Amplification System (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to amplify the signal. The reaction was stopped by using 50 μl of 0.3 M H2SO4, and plates were read at 490 nm. Statistical significance of the results was evaluated by analysis of variance, followed by the Tukey test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Insertional inactivation of the S. gordonii dlt operon and analysis of the d-alanine content in LTA.

To create a dltA mutant strain in S. gordonii PM14, the previously described dltA::ermAM construct (4) was introduced into the bacterium by transformation. Via allelic exchanges, the ermAM gene was inserted into the chromosome, resulting in the inactivation of dltA. The inactivation of the dltA gene was demonstrated by PCR using primers specific for the dltA gene that showed the amplification of the expected 2.3-kb DNA fragment from the mutant and the intact 1.4-kb dltA gene from the parent strain (data not shown). LTA samples from the parent strain and the dltA mutant were analyzed for d-alanine content. No detectable amount of d-alanine was found in the mutant LTA, while the parent LTA contained 3.27 μg of d-alanine per mg of LTA or 6.2 mol of d-alanine per mole of phosphorus. These results indicate that the dlt gene had been inactivated.

The dltA mutant and wild-type S. gordonii showed similar growth rates. The results from the cationic dye Alcian blue 8GX binding assay showed that the mutant had an increase in negative surface charges. The mutant bound 72.2% ± 1.64% of the Alcian blue in comparison to a 62.4% ± 1.67% binding by the wild type (P < 0.001).

Susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides.

The MIC of polymyxin B was determined for the S. gordonii PM14 wild type and the dltA mutant. The mutant was markedly more sensitive than the parent strain to polymyxin B. The MIC of polymyxin B displayed by the parent strain was 200 μg/ml, while that by the mutant was 3.125 μg/ml.

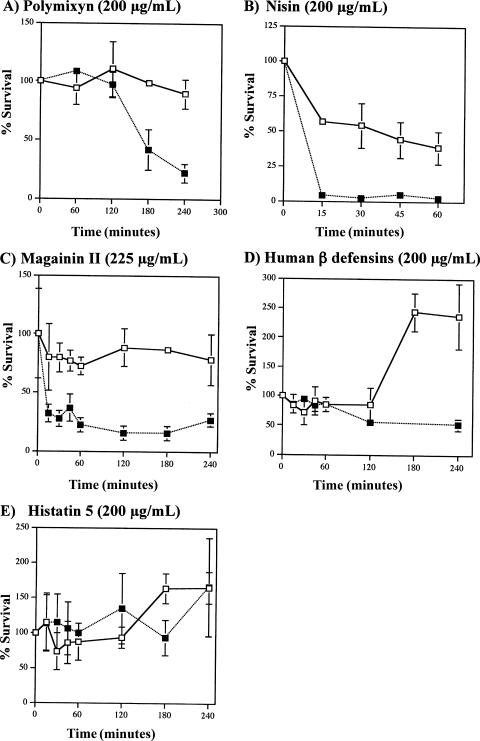

The susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides was further investigated in a kinetic inhibition assay. As shown in Fig. 1, the mutant was highly susceptible to inhibition by polymyxin B, nisin, and magainin II. The mutant was also susceptible to human β-defensins 1 and 2, while the parent was not inhibited and continued to grow in the presence of these two peptides. Interestingly, the mutant and the parent strains were not susceptible to histatin 5, an antimicrobial peptide found in human saliva, with a net charge of +5.

FIG. 1.

(A to E) Susceptibilities of S. gordonii PM14 (open squares) and the dltA mutant (filled squares) to various antimicrobial peptides. Data for panels A, B, and E represent the means of two independent experiments. Data in panels C and D are means ± standard deviations of triplicates from a single experiment.

Oral colonization in BALB/c mice.

The ability of the dltA mutant to colonize orally was tested with BALB/c mice. As shown in Table 2, the dltA mutant and parent bacteria showed no differences in colonization. Swabs at the time of euthanasia of the oral cavity, pharynx, trachea, and nasal cavity revealed similar levels of colonization at all of these sites between the parent and mutant strains. The oral cavity, pharynx, and trachea were colonized with a number of recombinant S. gordonii strains which represented a proportion of the anaerobes and facultative anaerobes normally found in these locations (0.8 to 6.8%). The nasal cavity was not well colonized by the either the parent or the mutant strain.

TABLE 2.

Colonization of BALB/c mice by S. gordonii PM14 and the dltA mutanta

| Site | PM14-inoculated mice (mean CFU ± SE)

|

DltA-inoculated mice (mean CFU ± SE)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total aerobes and facultative anaerobes | S. gordonii | Total aerobes and facultative anaerobes | S. gordonii | |

| Oral cavity | 82,600 ± 40,060 | 657 ± 576 (0.8%) | 34,063 ± 8,068 | 1,267 ± 381 (3.8%) |

| Pharynx | 8,500 ± 2,540 | 133 ± 105 (1.7%) | 5,753 ± 1,650 | 210 ± 80 (4.0%) |

| Trachea | 1,135 ± 498 | 13 ± 12 (1.2%) | 194 ± 76 | 13 ± 12 (6.8%) |

| Nasal cavity | 70 ± 61 | 0 (0%) | 1,480 ± 2,761 | 3 ± 7 (0.2%) |

The mean totals of CFU recovered from each site on the upper respiratory tract and oral cavity are shown along with the standard errors (SE) of the means (n = 5). The number in parentheses is the number of S. gordonii bacteria expressed as a percentage of the total aerobes and facultative anaerobes.

The production of anti-pertussis toxin and anti-S. gordonii serum IgG and salivary IgA antibodies following colonization was assessed by ELISA. IgG or IgA anti-pertussis and anti-S. gordonii antibodies were not found in sera and saliva samples from either group.

Binding of S. gordonii to mouse dendritic cells and HEp-2 cells.

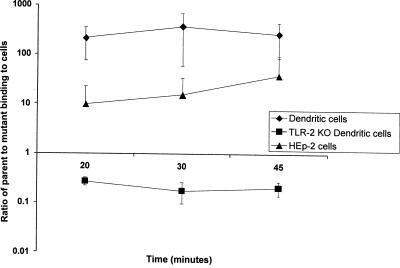

To determine if d-alanylation plays a role in binding to DCs, S. gordonii PM14 and the dltA mutant were incubated with immature bone marrow-derived DCs from wild-type and TLR2 knockout mice. These DC binding assays were carried out at 4°C to prevent phagocytosis. The parent S. gordonii strain bound 200- to 400-fold better to normal DCs than to cells of the dltA strain at all three time points (Fig. 2). An average of 1 to 3% (0.39 × 106 to 1 × 106 CFU/ml) of the parent bacteria added to an assay was cell bound, while the mutant exhibited an average of 0.01% (1.98 × 103 to 3.21 × 103 CFU/ml) binding to the normal DCs. The difference in the mean percentage of the parent versus that of mutant bacteria bound to normal DCs was statistically significant at the 30-min (P = 0.05) and 45-min (P = 0.04) time points.

FIG. 2.

Adherence of S. gordonii PM14 and the dltA mutant to bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from wild-type and TLR2 knockout (KO) mice and HEp-2 cells. Cells were cultured in vitro and incubated for 20, 30, or 45 min with early log-phase bacteria. Samples were run in triplicate, and the mean ratios of parent to mutant bacteria bound ± standard deviations of two or three independent experiments are shown.

Binding assays were also performed using TLR2 knockout DCs to investigate whether TLR2 was the receptor mediating this difference in binding between the parent and mutant S. gordonii to normal DCs. If the binding were mediated by TLR2, the lack of this receptor would impair the binding of the parent S. gordonii to the TLR2 knockout DCs. Surprisingly, the parent S. gordonii exhibited levels of binding to the TLR2 knockout DCs that were similar to those of the normal DCs, while the levels of dltA mutant binding to TLR2 knockout DCs increased (Fig. 2). The numbers of bound parent and mutant bacteria were 1.51 × 105 to 2.13 × 105 CFU/ml and 7.36 × 105 to 8.23 × 105 CFU/ml, respectively. The differences in binding levels between the parent and the mutant bacteria was not statistically significant at any of the time points.

d-Alanylation of LTA in S. pyogenes has been shown to play an important role in the attachment to human epithelial cells (19). In order to determine if the same was true for S. gordonii, the binding of the parent strain incubated with HEp-2 cells was compared to that of the dltA mutant incubated with HEp-2 cells. The results showed that the numbers of bound parent and mutant bacteria were 1.03 × 107 to 1.35 × 107 CFU/ml and 0.56 × 106 to 1.69 × 106 CFU/ml, respectively. Thus, there was generally more parent than mutant S. gordonii bound to the HEp-2 cells (∼10-fold), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Induction of cytokines by S. gordonii from dendritic cells.

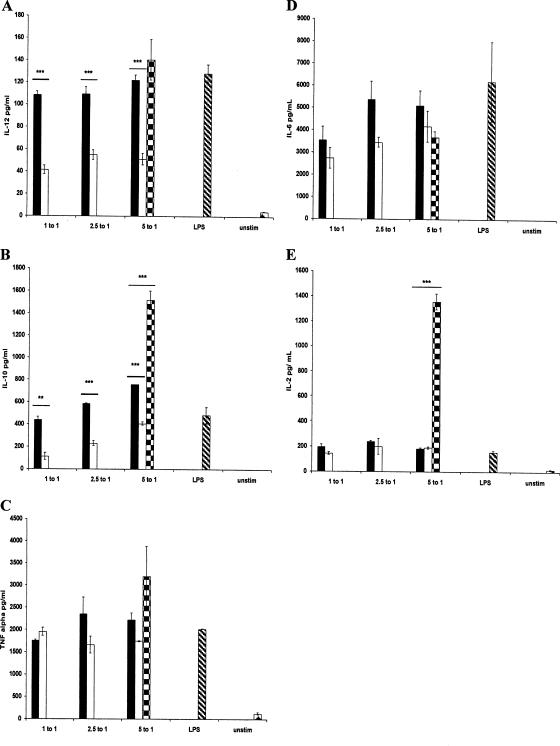

To determine if d-alanylation of LTA in S. gordonii plays a role in modulating the cytokine response, DCs were stimulated with S. gordonii, and the amounts of two proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-12), the Th2/regulatory cytokine IL-6, the regulatory cytokine IL-10, and the proinflammatory/regulatory cytokine IL-2 were assayed by ELISA. Both the parent and the mutant were able to induce higher levels of TNF-α, IL-12p70, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-2 than the unstimulated control (Fig. 3). As expected, DCs stimulated with LPS also produced these cytokines. The levels of IL-12p70 and IL-10 induced by the parent strain were significantly higher than that induced by the dltA mutant at all three ratios (Fig. 3A and B). Similar levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2 were induced by both S. gordonii strains (Fig. 3C to E). As a comparison, the cytokine profile induced by S. pyogenes was also examined. Like S. gordonii, S. pyogenes was capable of inducing higher levels of cytokines than the unstimulated control (Fig. 3). The level of IL-2 induced by S. pyogenes was markedly higher than that induced by S. gordonii. Similarly, the level of IL-10 induced by S. pyogenes was significantly higher than that induced by S. gordonii, while the TNF-α level induced by the former was higher but not statistically significant. The levels of IL-6 induced by S. pyogenes and S. gordonii were similar.

FIG. 3.

(A to E) Cytokine production by 6-day-old bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from BALB/c mice in response to stimulation by S. gordonii (black bars), the dltA mutant (white bars), and S. pyogenes (square checkers), or LPS (hatched bars) or left unstimulated (unstim; diamond checkers). DCs were stimulated with S. gordonii PM14 and its dltA mutant at a bacterium:DC ratio as shown. Stimulation with S. pyogenes was performed only at the 5:1 ratio. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01.

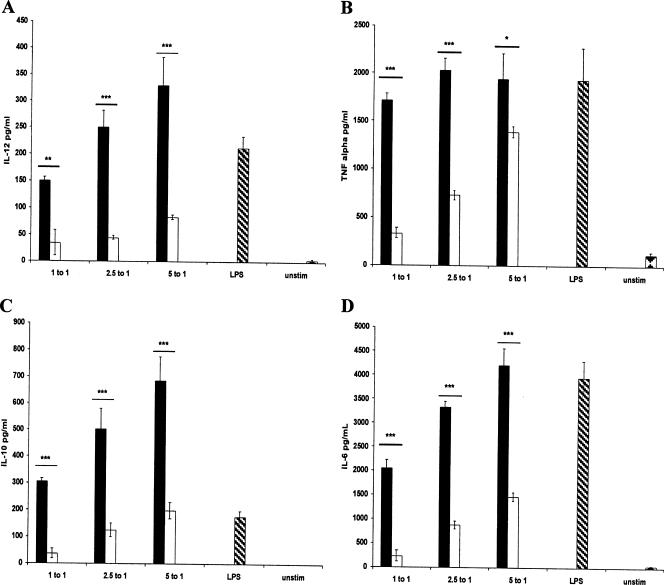

In order to determine whether TLR2 plays a role in mediating the cytokine profile induced by the S. gordonii strains, TLR2 knockout DCs were used with the stimulation assays. The results showed that both the parent and the dltA strains were able to induce TNF-α, IL-12p70, IL-6, and IL-10 production from the DCs (Fig. 4). However, a clear difference between the abilities of the parent and the dltA mutant to induce cytokine production by the TLR2 knockout DCs was observed. The mutant induced significantly less production of all 4 of these cytokines than the parent. The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 produced by the TLR2-deficient DCs were similar to that produced by the normal DCs in response to parent S. gordonii stimulation. However, the level of IL-12p70 produced by the TLR2-deficient DCs was 1.5 to 3.5 times higher than that produced by the normal DCs. Hence, the difference in response exhibited by normal and that of TLR2 knockout DCs was apparently due largely to the decreased cytokine levels induced by the dltA mutant. The levels of IL-2 were undetectable in any of the samples, including the LPS and unstimulated controls. It was also observed that stimulation with the S. gordonii strains had a clear dose-dependent effect on the cytokines levels that were induced (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12p70). When more bacteria were used to stimulate the DCs, higher levels of cytokines were produced.

FIG. 4.

(A to D) Cytokine production by 6-day-old bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from TLR2 knockout mice in response to stimulation by S. gordonii (black bars), the dltA mutant (white bars), or LPS (hatched bars) or left unstimulated (unstim; diamond checkers). DCs were stimulated with S. gordonii PM14 and its dltA mutant at the bacterium/DC ratios shown. Stimulation with S. pyogenes was not performed. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

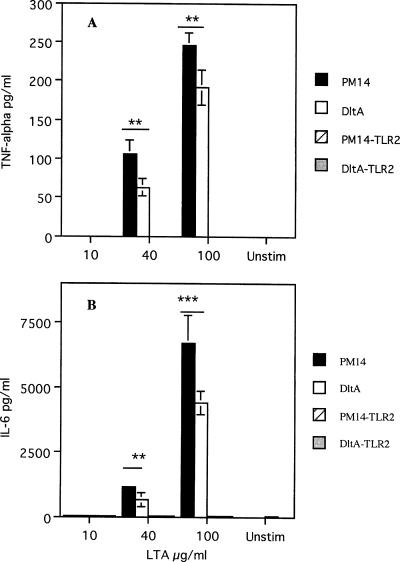

Induction of cytokines by LTA.

To further examine the role of d-alanylation of LTA in modulating cytokine response, DCs were stimulated with purified LTA. When wild-type DCs were stimulated with LTA, a dose-dependent production of TNF-α and IL-6 was observed, while no IL-12p70 or IL-10 was detected even when LTA was used at 400 μg/ml (Fig. 5). The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 elicited by the dltA mutant LTA were significantly lower than that elicited by the wild-type LTA. When TLR2 knockout DCs were stimulated with LTA, no detectable TNF α or IL-6 was observed. Similar to results with the wild-type DCs, IL-12p70 and IL-10 were not produced.

FIG. 5.

TNF-α and IL-6 production by 6-day-old bone marrow-derived wild-type dendritic cells in response to stimulation by LTA from S. gordonii PM14 or the dltA mutant (DltA). TLR2 knockout DCs stimulated PM14 LTA (PM14-TLR2) or dltA mutant LTA (DltA-TLR2) produced little or no response. Wild-type and TLR2 knockout DCs stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS produced 2,500 pg/ml TNF-α and 10,000 pg/ml IL-6 (data not plotted to simplify the graph). Unstim, unstimulated. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Several studies using other gram-positive organisms have demonstrated consistently that d-alanylation mutants are impaired in their ability to resist cationic peptide-mediated killing (9, 15, 19, 32, 33). Not surprisingly, the S. gordonii dltA mutant was found to be more susceptible to killing by several cationic peptides, including polymyxin B, nisin, magainin II, and human β defensins 1 and 2 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the dltA mutant did not exhibit increased susceptibility to histatin 5, which is an antimicrobial peptide commonly found in human saliva. It is possible that S. gordonii has other mechanisms to protect against lysis by histatin which are not affected by the lack of d-alanylation. Alternatively, it is possible that histatin 5 failed to exert its antimicrobial potential due to an inadequate amount of Zn2+ (34) or carbonate (8) present in our assay conditions; however, this remains to be tested.

Despite the previously described inability of an S. gordonii dltA mutant to form intragenic coaggregations (4), the mutant used in this study was able to effectively colonize the oral cavity, pharynx, and trachea of BALB/c mice (Table 2). This is in contrast to studies with S. aureus that show d-alanine substitution on LTA is essential for colonization in cotton rats (41). The undiminished ability of this bacterium to colonize was not surprising as S. gordonii produces a variety of adhesins that mediate binding and colonization such as the antigen I/II family polypeptides SspA and SspB and the sialic acid-binding protein Hsa. These proteins have recently been shown to be important for mediating primary adhesion events by interactions with human cell surface receptors (16).

Initially, it was thought that the d-alanine substitutes on LTA were protecting S. gordonii from lysis by host defense peptides naturally found in the oral cavity and that this mechanism prevented the presentation of this bacteria and its expressed antigens from eliciting a strong immune response. However, the present study demonstrates that the lack of d-alanylation on LTA does not affect the mucosal and humoral immune responses to the recombinant S. gordonii.

This is the first study of a mutation in the dlt operon resulting in altered binding to DCs. Others have previously demonstrated that dltA mutants displayed altered adherence to phagocytic cells. A study by Abachin et al. (1) demonstrated that a dlt mutant of Listeria monocytogenes exhibited decreased adherence to murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. In the current study, the S. gordonii dltA mutant displayed a significantly lower level of binding to DCs than its parent, suggesting that d-alanylation plays an important role in modulating the binding of this bacterium to DCs. This change in adherence could be the result of a simple increase in negative charge in the bacterial cell surface causing a decreased interaction with the negatively charged host cells. Our Alcian blue binding assay results showed that the dltA mutant has an increased negative charge.

Since it was known from the literature that LTA can directly bind to TLR2 (13, 16, 17), the binding of the dltA mutant to TLR2 knockout DCs was examined. The results showed that the parent bound equally well to the normal and the TLR2 knockout DCs. Remarkably, the absence of the TLR2 restored the mutant to wild-type levels of binding. These findings suggest that either the presence of TLR2 inhibits the binding of the dltA mutant or, perhaps more plausibly, that the absence of TLR2 allows for better nonspecific or specific interaction of other receptors on the DCs with the bacteria.

Our mouse DCs stimulation studies showed that S. gordonii is capable of inducing IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-2, and IL-10 production, which is consistent with a previous study by Corinti et al. (6) demonstrating that human DCs stimulated with a recombinant strain of S. gordonii expressing tetanus toxin fragment C induced the release of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12. Our results further reveal a differential induction of cytokines from DCs by a dltA mutant. The mutant exhibited a reduced ability to induce IL-12p70 and IL-10, indicating that d-alanylation plays a role in the response of DCs to S. gordonii. However, when purified LTA was used in the stimulation, no detectable IL-12p70 or IL-10 was observed. These results indicate that the observed IL-12p70 and IL-10 induced by S. gordonii whole cells was due to other components on the bacteria. The observed reduced ability of the mutant bacteria to induce these two cytokines coincided with the reduced binding to wild-type DCs. In the case of TLR2 knockout DCs, the mutant bacteria induced significantly less cytokines than the parent bacteria, while the binding was similar.

The DC stimulation experiments using purified LTA reveal three interesting findings. First, S. gordonii LTA is not capable of inducing IL-12p70 and IL-10. This is in contrast to findings reported by Deininger et al. (7) that purified LTA from S. aureus is capable of inducing IL-10 production by human whole blood. Second, S. gordonii LTA is capable of inducing TNF-α and IL-6 production, and TLR2 appears to be the receptor. These results are in general agreement with that reported for LTA from other bacteria (7, 14, 15, 35, 36). Third, S. gordonii LTA devoid of d-alanine induced significantly less TNF-α and IL-6. This is consistent with findings for purified LTA from group B Streptococcus (16) and S. aureus (8).

In addition to assessing the induction of cytokines from DCs in response to S. gordonii strains, the response to pathogenic group A Streptococcus (GAS) was also examined. The responses were compared in an attempt to determine whether there were any particular differences in the cytokine profiles induced, since one organism was able to avoid eliciting an immune response, while the pathogen was certain to elicit a strong one. Previous studies have shown that GAS induces strong Th1-type immune responses in monocytes, macrophages, and streptococci-infected tissues (28, 31, 40). It was shown in this study that GAS induced higher levels of TNF-α than the S. gordonii parent strain but not to a level that was statistically different. TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine, and naturally higher expression of this agent would promote a strong immune response. It is possible that even such small increase in TNF-α production could boost the Th1 response to GAS. GAS also induced significantly higher levels of IL-10 than the S. gordonii parent strain but similar levels of IL-6 and IL-12. IL-10 is a tolerance-promoting cytokine, but the expression of other cytokines can overcome its regulatory function; IL-2 is one of those cytokines. It was shown in this study that GAS induces large amounts of IL-2, while S. gordonii induces only low levels of IL-2. Low doses of IL-2 have been proven to be essential for the maintenance of regulatory T-cell function (38), but high levels of the same cytokine have been shown to reverse T-cell regulatory suppression and activate the immune response (37, 39). Therefore, the lack of IL-2 induction by S. gordonii may contribute to its inability to elicit a strong immune response.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that the d-alanylation of the LTA in S. gordonii contributes to relative resistance to cationic peptides, greater DC adherence, and immunomodulation of cytokine production from DCs. Thus, the incorporation of d-alanine into LTA may contribute to the persistence of this organism in the oral cavity by allowing S. gordonii to evade host defense peptides, increase contact with DCs that modulate the adaptive response, and subsequently promote a non-Th1 response.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Kolenbrander for providing pDC11 and J. Marshall (with permission from S. Akira) for the TLR2 knockout mice.

K. G. Chan was a recipient of a PGS-M scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abachin, E., C. Poyart, E. Pellegrini, E. Milohanic, F. Fiedler, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Formation of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is required for adhesion and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald, A. R., J. Baddiley, and S. Heptinstall. 1973. The alanine ester content and magnesium binding capacity of walls of Staphylococcus aureus H grown at different pH values. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 291:629-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemans, D. L., P. E. Kolenbrander, D. V. Debabov, Q. Zhang, R. D. Lunsford, H. Sakone, C. J. Whittaker, M. P. Heaton, and F. C. Neuhaus. 1999. Insertional inactivation of genes responsible for the d-alanylation of lipoteichoic acid in Streptococcus gordonii DL1 (challis) affects intrageneric coaggregations. Infect. Immun. 67:2464-2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins, L. V., S. A. Kristian, C. Weidenmaier, M. Faigle, K. P. Van Kessel, J. A. Van Strijp, F. Gotz, B. Neumeister, and A. Peschel. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus strains lacking d-alanine modifications of teichoic acids are highly susceptible to human neutrophil killing and are virulence attenuated in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 186:214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corinti, S., D. Medaglini, A. Cavani, M. Rescigno, G. Pozzi, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, and G. Girolomoni. 1999. Human dendritic cells very efficiently present a heterologous antigen expressed on the surface of recombinant gram-positive bacteria to CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 163:3029-3036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deininger, S., A. Stadelmaier, S. von Aulock, S. Morath, R. R. Schmidt, and T. Hartung. 2003. Definition of structural prerequisites for lipoteichoic acid-inducible cytokine induction by synthetic derivatives. J. Immunol. 170:4134-4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorschner, R. A., B. Lopez-Garcia, A. Peschel, D. Kraus, K. Morikawa, V. Nizet, and R. L. Gallo. 2006. The mammalian ionic environment dictates microbial susceptibility to antimicrobial defense peptides. FASEB J. 20:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabretti, F., C. Theilacker, L. Baldassarri, Z. Kaczynski, A. Kropec, O. Holst, and J. Huebner. 2006. Alanine esters of enterococcal lipoteichoic acid play a role in biofilm formation and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 74:4164-4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer, W. 1988. Physiology of lipoteichoic acids in bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 29:233-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, W., T. Mannsfeld, and G. Hagen. 1990. On the basic structure of poly(glycerophosphate) lipoteichoic acids. Biochem. Cell Biol. 68:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer, W., P. Rosel, and H. U. Koch. 1981. Effect of alanine ester substitution and other structural features of lipoteichoic acids on their inhibitory activity against autolysins of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 146:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock, R. E., and G. Diamond. 2000. The role of cationic antimicrobial peptides in innate host defenses. Trends Microbiol. 8:402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henneke, P., S. Morath, S. Uematsu, S. Weichert, M. Pfitzenmaier, O. Takeuchi, A. Muller, C. Poyart, S. Akira, R. Berner, G. Teti, A. Geyer, T. Hartung, P. Trieu-Cuot, D. L. Kasper, and D. T. Golenbock. 2005. Role of lipoteichoic acid in the phagocyte response to group B Streptococcus. J. Immunol. 174:6449-6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermann, C., I. Spreitzer, N. W. Schroder, S. Morath, M. D. Lehner, W. Fischer, C. Schutt, R. R. Schumann, and T. Hartung. 2002. Cytokine induction by purified lipoteichoic acids from various bacterial species: role of LBP, sCD14, CD14 and failure to induce IL-12 and subsequent IFN-gamma release. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:541-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakubovics, N. S., S. W. Kerrigan, A. H. Nobbs, N. Stromberg, C. J. van Dolleweerd, D. M. Cox, C. G. Kelly, and H. F. Jenkinson. 2005. Functions of cell surface-anchored antigen I/II family and Hsa polypeptides in interactions of Streptococcus gordonii with host receptors. Infect. Immun. 73:6629-6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkinson, H. F., R. A. Baker, and G. W. Tannock. 1996. A binding-lipoprotein-dependent oligopeptide transport system in Streptococcus gordonii essential for uptake of hexa- and heptapeptides. J. Bacteriol. 178:68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotloff, K. L., S. S. Wasserman, K. F. Jones, S. Livio, D. E. Hruby, C. A. Franke, and V. A. Fischetti. 2005. Clinical and microbiological responses of volunteers to combined intranasal and oral inoculation with a Streptococcus gordonii carrier strain intended for future use as a group A Streptococcus vaccine. Infect. Immun. 73:2360-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristian, S. A., V. Datta, C. Weidenmaier, R. Kansal, I. Fedtke, A. Peschel, R. L. Gallo, and V. Nizet. 2005. d-Alanylation of teichoic acids promotes group A Streptococcus antimicrobial peptide resistance, neutrophil survival, and epithelial cell invasion. J. Bacteriol. 187:6719-6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristian, S. A., X. Lauth, V. Nizet, F. Goetz, B. Neumeister, A. Peschel, and R. Landmann. 2003. Alanylation of teichoic acids protects Staphylococcus aureus against toll-like receptor 2-dependent host defense in a mouse tissue cage infection model. J. Infect. Dis. 188:414-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, C. W., S. F. Lee, and S. A. Halperin. 2004. Expression and immunogenicity of a recombinant diphtheria toxin fragment A in Streptococcus gordonii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, H. G., and M. K. Cowman. 1994. An agarose gel electrophoresis method for analysis of hyalutonan molecular weight distribution. Anal. Biochem. 219:278-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, S. F. 2003. Oral colonization and immune responses to Streptococcus gordonii: potential use as a vector to induce antibodies against respiratory pathogens. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, S. F., S. A. Halperin, H. Wang, and A. MacArthur. 2002. Oral colonization and immune responses to Streptococcus gordonii expressing a pertussis toxin S1 fragment in mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, L. M., and G. G. MacPherson. 1993. Antigen acquisition by dendritic cells: intestinal dendritic cells acquire antigen administered orally and can prime naive T cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 177:1299-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lutz, M. B., N. Kukutsch, A. L. Ogilvie, S. Rossner, F. Koch, N. Romani, and G. Schuler. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallaley, P. P., S. A. Halperin, A. Morris, A. Macmillan, and S. F. Lee. 2006. Expression of a pertussis toxin S1 fragment by inducible promoters in oral Streptococcus and the induction of immune responses during oral colonization in mice. Can. J. Microbiol. 52:436-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miettinen, M., S. Matikainen, J. Vuopio-Varkila, J. Pirhonen, K. Varkila, M. Kurimoto, and I. Julkunen. 1998. Lactobacilli and streptococci induce interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-18, and gamma interferon production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Infect. Immun. 66:6058-6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morath, S., A. Stadelmaier, A. Geyer, R. R. Schmidt, and T. Hartung. 2001. Structure-function relationship of cytokine induction by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Exp. Med. 193:393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuhaus, F. C., and J. Baddiley. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:686-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norrby-Teglund, A., R. Lustig, and M. Kotb. 1997. Differential induction of Th1 versus Th2 cytokines by group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome isolates. Infect. Immun. 65:5209-5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peschel, A., M. Otto, R. W. Jack, H. Kalbacher, G. Jung, and F. Gotz. 1999. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8405-8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poyart, C., E. Pellegrini, M. Marceau, M. Baptista, F. Jaubert, M. C. Lamy, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2003. Attenuated virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae deficient in d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is due to an increased susceptibility to defensins and phagocytic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1615-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rydengard, V., E. Andersson Nordahl, and A. Schmidtchen. 2006. Zinc potentiates the antibacterial effects of histidine-rich peptides against Enterococcus faecalis. FEBS J. 273:2399-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroder, N. W., S. Morath, C. Alexander, L. Hamann, T. Hartung, U. Zahringer, U. B. Gobel, J. R. Weber, and R. R. Schumann. 2003. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus activates immune cells via toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and CD14, whereas TLR-4 and MD-2 are not involved. J. Biol. Chem. 278:15587-15594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwandner, R., R. Dziarski, H. Wesche, M. Rothe, and C. J. Kirschning. 1999. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17406-17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi, T., T. Tagami, S. Yamazaki, T. Uede, J. Shimizu, N. Sakaguchi, T. W. Mak, and S. Sakaguchi. 2000. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Exp. Med. 192:303-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thornton, A. M., E. E. Donovan, C. A. Piccirillo, and E. M. Shevach. 2004. Cutting edge: IL-2 is critically required for the in vitro activation of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. J. Immunol. 172:6519-6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornton, A. M., and E. M. Shevach. 1998. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J. Exp. Med. 188:287-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veckman, V., M. Miettinen, S. Matikainen, R. Lande, E. Giacomini, E. M. Coccia, and I. Julkunen. 2003. Lactobacilli and streptococci induce inflammatory chemokine production in human macrophages that stimulates Th1 cell chemotaxis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weidenmaier, C., J. F. Kokai-Kun, S. A. Kristian, T. Chanturiya, H. Kalbacher, M. Gross, G. Nicholson, B. Neumeister, J. J. Mond, and A. Peschel. 2004. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10:243-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolters, P. J., K. M. Hilderbrandt, J. P. Dickie, and J. S. Anderson. 1990. Polymer length of teichuronic acid released from cell walls of Micrococcus luteus. J. Bacteriol. 172:5154-5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, X., and G. Arthur. 1992. Improved procedures for the determination of lipid phosphorus by malachite green. J. Lipid Res. 33:1233-1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]