Abstract

This study describes a comparative analysis of the Beijing mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit types of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Cape Town, South Africa, and East Asia. The results show a significant association between the frequency of occurrence of strains from defined Beijing sublineages and the human population from whom they were cultured (P < 0.0001).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with the Beijing genotype have been shown to be globally widespread and are particularly prevalent in East Asia, where over 80% of strains from the Beijing, China, region are of this genotype (5). It has been hypothesized that Beijing strains have evolved unique properties, including the ability to evade the protective effect of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination (19) and the ability to spread more efficiently than non-Beijing strains (2). However, the clinical presentations of patients with tuberculosis caused by a Beijing strain were found to vary between different geographical settings (3-5,16). Currently, it is not known whether the observed variability in clinical presentation is a function of the Beijing strain population found in particular geographical settings, is a function of the genetic composition of the human population, or is a function of a combination of these two variables.

This study aimed to test the hypothesis that host-pathogen compatibility determined the Beijing strain population structure in different host populations in different geographical settings. Cultures of M. tuberculosis isolates from patients of mixed ancestry (14) who were resident in Cape Town, South Africa (20), were classified as being of the Beijing genotype by spoligotyping (10). The Beijing strains were assigned to phylogenetic sublineages as described previously (8) and were genotyped by mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit (MIRU) typing (17).

During the study period (January 1993 to December 2004), 25 MIRU types were identified among 321 tuberculosis cases infected with a Beijing strain (Table 1). A comparison of the MIRU type data for the Beijing strains from Cape Town and previously published MIRU type data for the Beijing strains from East Asia (1, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18) showed that nine of the Beijing MIRU types (types MT01, MT08, MT11, MT18, MT19, MT21, MT28, MT33, and MT54) were shared between these geographical settings (Table 1). This suggests that the nine shared Beijing MIRU types represent founder strains that were introduced into Cape Town from East Asia, as the latter is thought to be the evolutionary origin of strains with a Beijing genotype (5, 7, 12). The definition of founder MIRU types was supported by their disproportionately high number (n = 267) compared to the number with nonfounder MIRU types (n = 54) in tuberculosis patients from Cape Town (z test for the hypothesis that the proportion of types were founder MIRU types = 0.5; P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Geographical distribution of Beijing MIRU types from Asia and South Africa

| MIRU type | Beijing sublineage(s)b | No. of copies in the following polymorphic MIRU loci:

|

No. (%) of strains fromh:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 10 | 16 | 20 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 31 | 39 | 40 | RUSc,d | CHNd | HKe | VNMd | SGPf | BGDg | CT-SA | ||

| MT01a | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 (2.2) | 5 (3.8) | 7 (3.3) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| MT02 | NAi | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 27 (60.0) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (3.6) | 7 (58.3) | ||

| MT04 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.7) | |||||

| MT05 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (2.2) | ||||||

| MT07 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 (4.4) | ||||||

| MT08a | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) | |||

| MT09 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.7) | |||||

| MT11a | 2, 3, 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 10 (22.2) | 42 (32.3) | 77 (36.5) | 10 (27.0) | 39 (69.6) | 3 (0.9), 2 (0.6), | |

| 8 (2.5)j | ||||||||||||||||||||

| MT12 | NA | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | |||||

| MT13 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 8 (3.8) | 1 (2.7) | |||||

| MT14 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (3.6) | |||

| MT16 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 (3.8) | 12 (5.7) | 5 (8.9) | ||||

| MT17 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | |||||

| MT18a | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | 5 (2.4) | 2 (3.6) | 7 (2.2) | |||

| MT19a | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 (0.9) | 1 (2.7) | 39 (12.1) | ||||

| MT20 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 19 (5.9) | ||||||

| MT21a | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 (3.1) | 6 (2.8) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (7.1) | 13 (4.0) | ||

| MT25 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 18 (5.6) | ||||||

| MT26 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MT27 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MT28a | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 16 (12.3) | 23 (10.9) | 4 (10.8) | 189 (58.9) | |||

| MT29 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MT33a | 6 | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 11 (8.5) | 4 (1.9) | 12 (32.4) | 3 (0.9) | |||

| MT37 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (8.3) | |||||

| MT43 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 (16.7) | ||||||

| MT44 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 (4.6) | 9 (4.3) | 1 (2.7) | |||||

| MT47 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 (2.3) | 6 (2.8) | 3 (8.1) | ||||

| MT48 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT49 | NA | NA | 2 | 7 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 (2.3) | ||||||

| MT50 | NA | NA | 2 | 5 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT51 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT52 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT53 | NA | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT54a | 6 | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 7 (5.4) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| MT55 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT56 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 9 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MT57 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 (1.5) | ||||||

| MTSGP76 | NA | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 (1.8) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA4 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA8 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA10 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTCT-SA11 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| MTHK1 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 (2.8) | ||||||

| MTHK2 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 (2.4) | ||||||

| MTHK3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 (2.4) | ||||||

| MTHK4 | NA | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 (1.9) | ||||||

| MTHK5 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 (1.4) | ||||||

| MTHK6 | NA | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 (1.4) | ||||||

| MTHK7 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTHK8 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTHK9 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTHK10 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTHK11 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

| MTHK12 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 (0.9) | ||||||

Founder MIRU types.

According to reference 8.

According to reference 13.

According to reference 12.

According to reference 9.

According to reference 15.

According to reference 1.

RUS, Russia; CHN, China; HK, Hong Kong; VNM, Vietnam; SGP, Singapore; BGD, Bangladesh; CT-SA, Cape Town, South Africa.

NA, not available.

Data are for sublineages 2, 3, and 6, respectively.

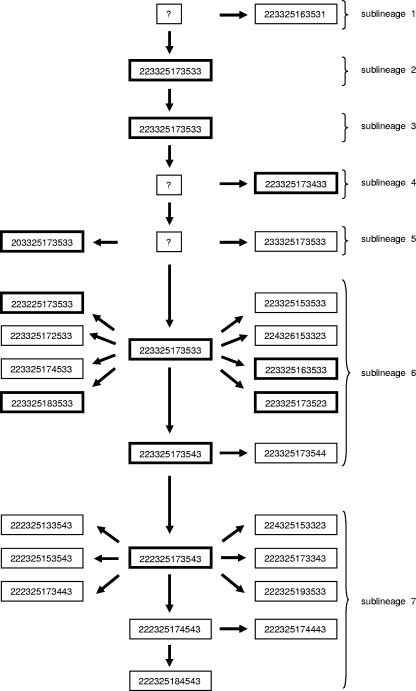

Superimposition of the Beijing MIRU type data onto the previously described phylogenetic tree of the Beijing strain family (8) provided a framework that could be used to predict the evolutionary order in which the 25 Beijing MIRU types had evolved (Fig. 1). From this prediction, the Beijing MIRU types could be partitioned into seven Beijing sublineages. The number of founder Beijing MIRU types was variable among the different Beijing sublineages (Fig. 1). Twenty-four of the Beijing MIRU types were unique to their respective sublineages, while the remaining Beijing MIRU type (MT11) was shared by three different sublineages (sublineages 2, 3, and 6) (Fig. 1 and Table 1), suggesting that MT11 was an ancestral Beijing MIRU type (12).

FIG. 1.

Evolutionary scenario of Beijing MIRU types according to Beijing sublineage. Beijing MIRU types were grouped according to their respective Beijing sublineages (8), and the most parsimonious evolutionary order was proposed. The Beijing MIRU types are indicated within each box. Founder Beijing MIRU types are indicated by bold boxes. Unknown Beijing MIRU types are indicated by “?.”

To determine the propensity of Beijing strains from the different sublineages to spread in the human population in Cape Town, the number of cases in circulation within each sublineage was compared to the number of founder strains for that sublineage (Table 1). The number of representatives of these founder strains was shown to be overrepresented in sublineage 7 (n = 233 cases from one founder strain) compared with the numbers in sublineages 1 to 6 (n = 88 cases from eight founder strains) (z test for the hypothesis that the proportion of sublineage 7 cases = 0.11; P < 0.001). In comparison, founder Beijing MIRU types MT01, MT08, MT11, MT18, MT19, MT21, MT33, and MT54 were overrepresented in the human population in East Asia (China, 73/130; Hong Kong, 108/211; Vietnam, 25/37; and Singapore, 45/56) compared to their representation in Cape Town, South Africa (79/321) (Fisher's exact test odds ratio [OR], 4.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.06 to 5.77; P < 0.0001).

A significant association between the frequency of occurrence of strains of defined Beijing sublineages and the human population from whom they were isolated was observed (for sublineages 1 to 6, n = 88 for Cape Town and n = 253 for East Asia; for sublineage 7, n = 233 for Cape Town and n = 43 for East Asia; Fisher's exact test OR, 15.58; 95% CI, 10.38 to 23.38; P < 0.0001).

It is unlikely that these findings can be explained by multiple importations of founder strains of sublineage 7 in preference to founder strains of sublineages 1 to 6, given that immigrants to South Africa came from many different geographical regions in East Asia and that sublineage 7 founder strains are less frequently observed in East Asia. Accordingly, we propose that the situation in Cape Town represents an approximation to a common starting point for all the founder strains introduced, with those best adapted to the local population spreading most efficiently. This could be due to the innate characteristics of the strains within defined Beijing sublineages or the local host population. Susceptibility to M. tuberculosis per se has frequently been associated with the HLA genotype (11), and HLA allele frequencies are known to differ widely between human populations with different histories, with certain alleles totally absent in some populations. Our conclusion differs from that of Gagneux et al. (6), as we demonstrate that strains from a defined sublineage (a subset of strains from an evolutionary lineage) may have been selected by a human population in a defined geographical setting.

In summary, the global success of the Beijing lineage may reflect either the selection of defined sublineages in different geographical settings by distinct human populations or the adaptation of strains in a defined sublineage to spread more readily in a distinct human population. We acknowledge that these contrasting conclusions cannot be easily distinguished with the available data. However, the emergence of a sublineage of Beijing strains with increased pathogenicity may have important implications for the Tuberculosis Control Program. Early diagnosis and contact tracing will be essential to curb the spread of these strains. Furthermore, it will be important to ensure that future vaccines protect against these strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank the TB in the 21st Century Consortium, the Harry Crossley Foundation, and the European Commission 6th Framework Program on Research Technological Development Demonstration (project no. 037919) for financially supporting this project.

We thank M. Kidd for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banu, S., S. V. Gordon, S. Palmer, M. R. Islam, S. Ahmed, K. M. Alam, S. T. Cole, and R. Brosch. 2004. Genotypic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Bangladesh and prevalence of the Beijing strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:674-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bifani, P. J., B. Mathema, N. E. Kurepina, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2002. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 10:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgdorff, M. W., H. van Deutekom, P. E. de Haas, K. Kremer, and D. van Soolingen. 2004. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Beijing genotype strains not associated with radiological presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 84:337-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drobniewski, F., Y. Balabanova, V. Nikolayevsky, M. Ruddy, S. Kuznetzov, S. Zakharova, A. Melentyev, and I. Fedorin. 2005. Drug-resistant tuberculosis, clinical virulence, and the dominance of the Beijing strain family in Russia. JAMA 293:2726-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Concerted Action on New Generation Genetic Markers and Techniques for the Epidemiology and Control of Tuberculosis. 2006. Beijing/W genotype Mycobacterium tuberculosis and drug resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:736-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagneux, S., K. DeRiemer, T. Van, M. Kato-Maeda, B. C. de Jong, S. Narayanan, M. Nicol, S. Niemann, K. Kremer, M. C. Gutierrez, M. Hilty, P. C. Hopewell, and P. M. Small. 2006. Variable host-pathogen compatibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2869-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glynn, J. R., J. Whiteley, P. J. Bifani, K. Kremer, and D. van Soolingen. 2002. Worldwide occurrence of Beijing/W strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:843-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanekom, M., G. D. van der Spuy, E. Streicher, S. L. Ndabambi, C. R. McEvoy, M. Kidd, N. Beyers, T. C. Victor, P. D. van Helden, and R. M. Warren. 2007. A recently evolved sublineage of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strain family is associated with an increased ability to spread and cause disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1483-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kam, K. M., C. W. Yip, L. W. Tse, K. L. Wong, T. K. Lam, K. Kremer, B. K. Au, and D. van Soolingen. 2005. Utility of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit typing for differentiating multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates of the Beijing family. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:306-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamerbeek, J., L. Schouls, A. Kolk, M. van Agterveld, D. van Soolingen, S. Kuijper, A. Bunschoten, H. Molhuizen, R. Shaw, M. Goyal, and J. Van Embden. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lombard, Z., A. E. Brune, E. G. Hoal, C. Babb, P. D. van Helden, J. T. Epplen, and L. Bornman. 2006. HLA class II disease associations in southern Africa. Tissue Antigens 67:97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokrousov, I., H. M. Ly, T. Otten, N. N. Lan, B. Vyshnevskyi, S. Hoffner, and O. Narvskaya. 2005. Origin and primary dispersal of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype: clues from human phylogeography. Genome Res. 15:1357-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokrousov, I., O. Narvskaya, E. Limeschenko, A. Vyazovaya, T. Otten, and B. Vyshnevskiy. 2004. Analysis of the allelic diversity of the mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the Beijing family: practical implications and evolutionary considerations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2438-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurse, G. T., J. S. Weiner, and T. Jenkins. 1985. The peoples of southern Africa and their affinities, p. 410. Clarendon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 15.Sun, Y. J., R. Bellamy, A. S. Lee, S. T. Ng, S. Ravindran, S. Y. Wong, C. Locht, P. Supply, and N. I. Paton. 2004. Use of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing to examine genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Singapore. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1986-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, Y. J., T. K. Lim, A. K. Ong, B. C. Ho, G. T. Seah, and N. I. Paton. 2006. Tuberculosis associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing and non-Beijing genotypes: a clinical and immunological comparison. BMC Infect. Dis. 6:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Supply, P., S. Lesjean, E. Savine, K. Kremer, D. van Soolingen, and C. Locht. 2001. Automated high-throughput genotyping for study of global epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3563-3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Supply, P., R. M. Warren, A. L. Banuls, S. Lesjean, G. D. van der Spuy, L. A. Lewis, M. Tibayrenc, P. D. van Helden, and C. Locht. 2003. Linkage disequilibrium between minisatellite loci supports clonal evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a high tuberculosis incidence area. Mol. Microbiol. 47:529-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Soolingen, D., L. Qian, P. E. de Haas, J. T. Douglas, H. Traore, F. Portaels, H. Z. Qing, D. Enkhsaikan, P. Nymadawa, and J. D. van Embden. 1995. Predominance of a single genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in countries of east Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3234-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verver, S., R. M. Warren, Z. Munch, E. Vynnycky, P. D. van Helden, M. Richardson, G. D. van der Spuy, D. A. Enarson, M. W. Borgdorff, M. A. Behr, and N. Beyers. 2004. Transmission of tuberculosis in a high incidence urban community in South Africa. Int. J. Epidemiol. 33:351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]