Abstract

A Luminex suspension array, which had been developed for identification of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates, was tested by genotyping a set of 58 mostly clinical isolates. All genotypes of C. neoformans and C. gattii were included. In addition, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained from patients with cryptococcal meningitis was used to investigate the feasibility of the technique for identification of the infecting strain. The suspension array correctly identified haploid isolates in all cases. Furthermore, hybrid isolates possessing two alleles of the Luminex probe region could be identified as hybrids. In CSF specimens, the genotype of the cryptococcal strains responsible for infection could be identified after optimization of the PCR conditions. However, further optimization of the DNA extraction protocol is needed to enhance the usability of the method in clinical practice.

Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii are closely related pathogenic yeasts, as indicated by the previous description of C. gattii as a variety of C. neoformans (16). Recently, C. gattii has been described as a separate species because of differences in ecology, biochemical, and molecular characteristics (17, 18). C. neoformans and C. gattii both may cause meningoencephalitis, which is fatal unless treated. C. neoformans occurs globally and is found primarily in immunocompromised individuals, e.g., human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Although the incidence of cryptococcosis in AIDS patients has decreased because of the introduction of the highly active antiretroviral treatment, cryptococcosis remains a serious disease, with a mortality rate of 10 to 30% in regions where access to treatment is limited (3, 22), and it continues to be the most important cause of fungal meningitis in immunocompromised patients. In contrast to C. neoformans, C. gattii mainly infects immunocompetent individuals and was thought to occur only in (sub)tropical areas. However, one of the genotypic groups of C. gattii is causing an ongoing outbreak on Vancouver Island (14, 15, 27), which indicates that C. gattii may also occur in more temperate areas.

C. neoformans and C. gattii differ not only in host range and geographic distribution, but they also differ in clinical manifestation. Although both species infect the central nervous system, C. gattii appears to invade the brain parenchyma more commonly than C. neoformans. Furthermore, in C. gattii-infected patients, pulmonary infections are more likely and pulmonary mass-like lesions occur more commonly than in C. neoformans-infected patients (23, 26). Patients infected with C. gattii seem to have had their symptoms longer before presentation and therapy is often needed for a longer period of time (23, 26). Because of the differences in clinical manifestations and the outcomes of disease, it is important to accurately identify the species responsible for the infection.

Six haploid genotypic groups within C. neoformans and C. gattii can be distinguished by several different molecular methods, e.g., by amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis (4), PCR fingerprinting (21), and intergenic spacer (IGS) genotyping (10). The haploid groups within C. neoformans correspond to the two varieties C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans, while C. gattii can be divided into four genotypic groups. Besides these haploid groups, hybrids have been described as well. Hybrids between the two varieties of C. neoformans exist, these are the so-called AD hybrids (4, 6, 20, 28), and hybrids between C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. gattii have recently been described (5). The different genotypic groups and the relationship between variety, serotype, and the different genotyping methods are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the varieties, serotypes, and genotypes within C. neoformans and C. gattii.

| Species | Serotypea,b | AFLP genotype b,c | Molecular genotypea | IGS genotyped | Luminex probee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. neoformans | CNNb | ||||

| C. neoformans var. grubii | A | 1 | VNI/VNII | 1A/1B/1C | CNN1b |

| C. neoformans var. grubii × C. neoformans var. neoformans hybrid | AD | 3 | VNIII | ||

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | D | 2 | VNIV | 2A/2B/2C | CNN2d |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans × C. gattii AFLP4 hybrid | BD | 8 | |||

| C. gattii | CNG | ||||

| C. gattii | B/C | 4 | VGI | 4A/4B/4C | CNG4c |

| C. gattii | B/C | 5 | VGIII | 5 | CNG5b |

| C. gattii | B/C | 6 | VGII | 3 | CNG3 |

| C. gattii | B/C | 7 | VGIV | 6 | CNG6 |

Unfortunately, the diagnostic methods which are currently used do not discriminate between all genotypic groups. As a consequence, the differences in hosts and symptoms between the genotypic groups are not known, which is especially true for the genotypic groups within C. gattii. It is likely that more differences in host range and symptoms will be found when the exact genotype of the infecting cryptococcal strain is determined. Another disadvantage of the current diagnostic methods is that they take a considerable amount of time to complete (e.g., culturing) or they can only be used for a limited number of species (e.g., antigen detection). Recently, Luminex xMAP technology has been adapted for the detection of the genotypes within C. neoformans and C. gattii (9). The xMAP technology is based on uniquely color-coded microspheres, which allows as many as one hundred different species to be detected in a single reaction. This technology has been used for the detection of several species of bacteria and fungi (7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 24, 31). Recently, xMAP technology has been used in several diagnostic kits for the detection of bacterial and viral pathogens.

In our study, we used a set of 48 haploid and 10 hybrid isolates to test a Luminex suspension array, which had been developed for identification of C. neoformans and C. gattii strains (9). Our set contained isolates obtained from Dutch cryptococcosis patients in the period between 1977 and 2001, as well as C. gattii isolates from our own collection. In addition, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens obtained from patients diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis were used to investigate the feasibility of this Luminex suspension array for the identification of cryptococci in clinical specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genotyping of cryptococcal isolates.

Thirty-four isolates obtained from Dutch patients and maintained in the cryptococcal collection of The Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis (Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were used for the genotyping assay. Because almost all of these isolates were C. neoformans, we included twenty additional C. gattii isolates and four additional hybrid isolates from our own collection. The origins of the haploid and hybrid isolates are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Origins of haploid isolates and overview of results obtained by AFLP analysis, mating-serotype-specific PCRs, and Luminex suspension array

| Isolatea | Source of isolationb | Location | AFLP genotype | Mating type and serotype | Positive Luminex probes | Luminex identification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMC770704 | CSF, HIV-negative woman, age 22 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC830410 | CSF, HIV-negative woman, age 58 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC860743 | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 47 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC880696 | Jugular gland, man, age 19 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC900239 | CSF, immunocompetent man, age 27 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC900321 | Lung, AIDS patient, man, age 43 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC900906 | CSF, immunocompetent woman, age 49 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC901081 | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 47 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC922148 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 29 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC931394 | CSF, HIV-negative, immunocompromised man, age 52 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC940211 | CSF, AIDS suspected, man, age 30 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC940580 | CSF, HIV-negative, immunocompromised man, age 73 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC940751 | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 44 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC951535 | CSF, prednisone usage, HIV-negative, immunocompromised man, age 58 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC981683 | CSF, AIDS patient, woman, age 23 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC990558 | CSF, encephalopathy, AIDS patient, man, age 37 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC2040734 | CSF, man, age 46 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC9402891 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 45 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| JS9901 | CSF, sarcoidosis, man, age 43 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| MN | HIV-positive man, age 30 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| P1953 | HIV-negative, immunocompromised man, age 65 | The Netherlands | AFLP1 | αA | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) | This study |

| AMC890401 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 35 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | aD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| AMC940038 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 29 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | aD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| AMC941354 | CSF, HIV-negative, immunocompromised man, age 69 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | αD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| AMC2010488 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 50 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | αD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| AMC2031402 | CSF, man, age 65 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | αD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| AMC2020797A | CSF, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, woman, age 41 | The Netherlands | AFLP2 | αD | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | This study |

| CBS1622 | Tumor, man | France | AFLP4 | B | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| CBS6289 | Subculture of type strain of C. neoformans var. gattii (RV20186: human CSF, Zaire) | AFLP4 | B | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | Boekhout et al. (4) | |

| CBS7229 | Meningitis, type strain of C. neoformans var. shanghaiensis | China | AFLP4 | B | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| CBS883 | Infected skin, syntype C. hondurianus | Honduras | AFLP4 | B | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| N114 | HIV-positive man, age 47 | The Netherlands | AFLP4 | NDb | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | This study |

| RV54130 | Second isolate of C. neoformans var. shanghaiensis | China | AFLP4 | B | CNG, CNG4c | C. gattii (AFLP4) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| CBS6955 | CSF, type strain of Filobasidiella bacillispora | California | AFLP5 | C | CNG, CNG5b | C. gattii (AFLP5) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| CBS6993 | Human CSF | California | AFLP5 | C | CNG, CNG5b | C. gattii (AFLP5) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| CBS8755 | Detritus of almond tree | Colombia | AFLP5 | C | CNG, CNG5b | C. gattii (AFLP5) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| WM726 | Eucalyptus citriodora | San Diego, CA | AFLP5 | B | CNG, CNG5b | C. gattii (AFLP5) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| 113A-5 | Air sample from beneath Douglas fir tree | Vancouver Island, Canada | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Kidd et al. (15) |

| AV54 | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 31 | Greece | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Velegraki et al. (29) |

| AV55 | Immunocompromised woman, age 26 | Greece | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Velegraki et al. (29) |

| CBS6956 | Sputum, immunocompetent human | Seattle, WA | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Boekhout et al. (4) |

| A1MF3179 | Sputum, immunocompetent man | Vancouver, Canada | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Kidd et al. (15) |

| A1MR265 | Bronchial wash, immunocompetent man | Vancouver Island, Canada | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Kidd et al. (15) |

| ENV133 | Douglas fir tree | Vancouver Island, Canada | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Kidd et al. (15) |

| RB28 | Tree stump near alder tree | Vancouver Island, Canada | AFLP6 | B | CNG, CNG3 | C. gattii (AFLP6) | Kidd et al. (15) |

| B5748 | HIV-positive human | India | AFLP7 | B | CNG, CNG6 | C. gattii (AFLP7) | Diaz and Fell (9) |

| M27055 | Clinical specimen | Johannesburg, South Africa | AFLP7 | C | CNG, CNG6 | C. gattii (AFLP7) | Latouche et al. (19) |

| WM779 | Cheetah | Johannesburg, South Africa | AFLP7 | C | CNG, CNG6 | C. gattii (AFLP7) | Kidd et al. (15) |

AMC, The Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; CBS, CBS—Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; RV, BCCM/IHEM Biomedical Fungi and Yeast Collection, Brussels, Belgium; WM, Wieland Meyer, Molecular Mycology Research Laboratory, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

ND, not determined.

TABLE 3.

Origin of hybrid isolates and overview of results obtained by AFLP analysis, sequence analysis, mating-serotype-specific PCRs, and Luminex suspension arraya

| Isolateb | Source of isolation | Location | AFLP genotype | Mating type and serotype | Positive Luminex probes | Luminex identification | IGS1 sequences (no. of alleles) | CNLAC1 sequences (no. of alleles) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMC881205I | CSF, HIV-positive man | The Netherlands | AFLP3 | aA-αD | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) | 2 | 2 | This study |

| CDC92-26 | CDC | AFLP3 | aA-αD | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) | 2 | 2 | This study | |

| Kl#1 | Progeny laboratory crossing H99 5-FOAr × JEC171 | AFLP3 | aD-αA | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) | 2 | 2 | Lengeler et al. (20) | |

| Kl#45 | Progeny laboratory crossing H99 5-FOAr × JEC171 | AFLP3 | aD-αA | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) | 2 | 2 | Lengeler et al. (20) | |

| ZG287 | Duke Medical Center permanent strain collection | AFLP3 | aD-αA | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) | 2 | 2 | Lengeler et al. (20) | |

| AMC890351 | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 44 | The Netherlands | AFLP3 | aD-αA | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | 1 | 2 | This study |

| AMC891529 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 31 | The Netherlands | AFLP3 | aD-αA | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) | 1 | 2 | This study |

| AMC770616 (=CBS10488) | CSF, brain tumor surgery, man, age 23 | The Netherlands | AFLP8 | aD-αB | CNNb, CNN2d, CNG, CNG4c | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. neoformans and AFLP4 C. gattii (AFLP8) | 2 | 2 | Bovers et al. (5) |

| AMC2010404 (=CBS10489) | CSF, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, man, age 35 | The Netherlands | AFLP8 | aD-αB | CNNb, CNN2d, CNG, CNG4c | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. neoformans and AFLP4 C. gattii (AFLP8) | 2 | 2 | Bovers et al. (5) |

| AMC2011225 (=CBS10490) | CSF, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, man, age 36 | The Netherlands | AFLP8 | aD-αB | CNNb, CNN2d, CNG, CNG4c | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. neoformans and AFLP4 C. gattii (AFLP8) | 2 | 2 | Bovers et al. (5) |

All isolates were diploid.

AMC, The Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

DNA was isolated from cultures as described by Bovers et al. (5). Isolates that had not been genotyped before were analyzed by AFLP (4) and C. neoformans mating- and serotype-specific PCRs. PCR amplifications were performed in 20-μl volumes containing 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.3), 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gentaur, Bruxelles, Belgium), 2 to 3 μl of template DNA, and 0.1 μM of both primers. Amplification conditions were as follows: for serotype AD-MATα-specific primer pair JOHE1671/1672 (20), 96°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of 96°C for 30 s, 66°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min; for serotype A-specific primer pair JOHE3241/JOHE2596 (20) and serotype D-specific primer pair JOHE3240/JOHE2596 (20), 96°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of 96°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, and a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min. PCR conditions for the first serotype A-MATa-specific primer pair JOHE5169/JOHE5170 (20), the second serotype A-MATa-specific primer pair JOHE7270/JOHE7272 (1), the serotype A-MATα-specific primer pair JOHE7264/JOHE7265 (1), the serotype D-MATa-specific primer pair JOHE7273/JOHE7275 (1), and the serotype D-MATα-specific primer pair JOHE7267/JOHE7268 (1) were as follows: 96°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 96°C for 15 s, 66°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min.

Flow cytometry and sequencing of hybrid isolates.

The diploid nature of all hybrid isolates was confirmed by flow cytometry according to the method of Bovers et al. (5). Furthermore, partial sequences of the IGS1 region of the ribosomal DNA and laccase (CNLAC1) gene were determined for all hybrid isolates. The primer sequences were those used by Diaz et al. (12) and Xu et al. (32). The amplicons were cloned into Escherichia coli DH5α cells with a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Clones were picked randomly, amplified, and purified with a GFX PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NY). A BigDye v3.1 Chemistry kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for sequencing, and the amplicons were analyzed on an ABI 3700XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Clinical specimens.

Clinical specimens were obtained from The Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis in Amsterdam, the University Medical Centre in Utrecht, and the Erasmus Medisch Centrum in Rotterdam, all in The Netherlands, and the University Hospital Gasthuisberg in Leuven, Belgium. CSF from patients with culture-proven cryptococcal meningitis had been stored for up to five years at −80°C. The origins and volumes of the CSF specimens are described in Table 4. After thawing the CSF samples, they were centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000 × g and the supernatant was removed. Five hundred microliters of distilled water was added, and the pellet was resuspended to remove human cells that might be present in the CSF. The samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000 × g and the supernatant was removed. One milliliter of Novozym 234 (1 mg/ml) (Novo Industri, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) suspended in sorbitol buffer (1 M sorbitol, 0.1 M sodiumcitrate; pH 5.5) was added to the samples. The samples were incubated for one hour at 37°C to generate protoplasts, after which the samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 4,600 × g and the supernatant was removed. The tissue protocol of the QIAamp DNA Micro kit (QIAGEN, Venlo, The Netherlands) was used for DNA isolation. The DNA was eluted with 35 μl of AE buffer from the kit.

TABLE 4.

Origin and volume of CSF for which amplicons could be obtained and the results of Luminex identification

| Clinical specimena | Source of isolation | Vol (μl) | Positive Luminex probes | Luminex identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMC2031402 | CSF, man, age 65 | 400 | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) |

| AMC2031845 | CSF, man, age 73 | 400 | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) |

| AMC2040592 | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 29 | 400 | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) |

| AMC2010488 (=JS2002) | CSF, AIDS patient, man, age 50 | 385 | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) |

| JS9901 | CSF, sarcoidosis, man, age 43 | 185 | No positive probes | |

| AMC2010576 (=JS2003) | CSF, HIV-positive man, age 46 | 85 | No positive probes | |

| L4 | CSF | 185 | CNNb, CNN2d | C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2) |

| L5C (=535615) | CSF, some blood present | 1,230 | CNNb, CNN1b | C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1) |

| L5D (=536140) | CSF | 2,230 | CNNb, CNN1b, CNN2d | Hybrid between C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP3) |

AMC, The Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; JS and L, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Luminex suspension array.

The Luminex suspension array, which detects 5′ biotin-labeled PCR amplicons hybridized to specific capture probes, was performed as described by Diaz and Fell (9). Specific oligonucleotide probes for each of the six haploid genotypic groups within the C. neoformans species complex as well as oligonucleotide probes targeting either C. neoformans or C. gattii were used. All probes had been designed based on the IGS1 region of the ribosomal DNA (9). An overview of the targets of each probe is given in Table 1. The probes were synthesized with a 5′-end Amino C-12 modification (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and covalently coupled to different sets of 5.6-μm polystyrene carboxylated microspheres using a slightly modified carbodiimide method (8). Each microsphere set (MiraiBio, Alameda, CA) contains a unique spectral address by combining different ratios of red and infrared fluorochromes. In a typical reaction, 5 × 106 microspheres were resuspended in 25 μl 0.1 M MES (2[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid), pH 4.5, with a determined amount of probe (0.2 to 0.5 nmol). Probe coupling was performed as described by Diaz and Fell (8), and the microspheres were subsequently resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8). A microsphere mixture was made by adding approximately 5,000 microspheres for each of the eight probes to a 1.5× TMAC (3 M tetramethyl ammonium chloride, 50 mM Tris [pH 8], 4 mM EDTA [pH 8], 0.1% Sarkosyl) solution.

To amplify the IGS1 region, forward primer IG1F (5′-CAG ACG ACT TGA ATG GGA ACG-3′) and reverse primer IG2R (5′-ATG CAT AGA AAG CTG TTG G-3′) were used (12). The reverse primer was biotinylated at the 5′ end. The 1× HotStarTaq MasterMix (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 2.5 units of HotStarTaq polymerase was used for all PCRs. DNA had been extracted from the cryptococcal isolates prior to amplification, although Diaz and Fell (9) directly used yeast cells for PCR amplification. PCRs were carried out in a total volume of 25 μl. Primers IG1F and IG2R (0.6 μM) and 1.5 μl of template DNA were added to the MasterMix. Amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension step of 72°C for 7 min.

PCR amplification of the first two clinical samples was carried out using the HotStarTaq MasterMix in a 50-μl total volume containing 3 μl of DNA and 0.4 μM of both primer IG1F and primer IG2R. Amplification conditions were as described above.

Optimization of the PCR conditions resulted in the following reaction conditions, which were used for the remaining clinical samples. PCR amplification was carried out with the HotStarTaq MasterMix in a 50-μl total volume containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 8 μl of DNA, and 0.6 μM of both primer IG1F and primer IG2R. Amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 69°C for 30 s, and a final extension step of 69°C for 9 min. Amplicons were cleaned with a QIAGEN purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and eluted with elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]).

To genotype the cryptococcal isolates, 5 μl of biotinylated amplicon was diluted with 12 μl of TE buffer (pH 8), and to genotype the clinical samples, 15 μl of biotinylated amplicon was diluted with 2 μl of TE buffer (pH 8). Thirty-three microliters of the microsphere mixture was added. Each amplicon was tested in duplicate with the Luminex suspension array. The hybridization reaction was performed as described by Diaz and Fell (9).

The hybridized samples were analyzed on the Luminex 100 analyzer (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX). One hundred microspheres of each set were analyzed, which represents a hundred replicate measurements. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were calculated with a digital signal processor and Luminex 1.7 proprietary software. A positive signal was defined as a signal that is at least twice the background level after subtraction of the background.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences were deposited at GenBank under the accession numbers DQ286656 to DQ286661, DQ286665 to DQ286670, and EF100569 to EF100594.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

AFLP analysis and mating-serotype-specific PCRs performed on the isolates that had not been genotyped before showed that twenty-one isolates belonged to C. neoformans var. grubii MATα serotype A (AFLP1), four isolates were C. neoformans var. neoformans MATα serotype D (AFLP2), and two isolates were C. neoformans var. neoformans MATa serotype D (AFLP2). Finally, one isolate belonged to the C. gattii AFLP4 genotype. Some hybrid isolates between the two varieties of C. neoformans were detected: two MATa serotype A-MATα serotype D (AFLP3) and two MATa serotype D-MATα serotype A (AFLP3) isolates. Results of the AFLP analysis and the mating-serotype-specific PCRs are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

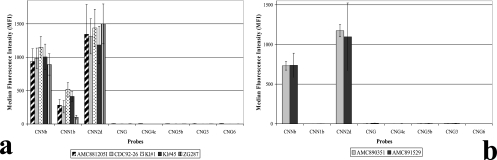

All haploid isolates were identified by two Luminex suspension array probes (Fig. 1). Probes CNNb and CNN1b identified the AFLP1 isolates as C. neoformans var. grubii (AFLP1), and probes CNNb and CNN2d identified the AFLP2 isolates as C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2). Probe CNG correctly identified all C. gattii isolates as C. gattii. In addition, probe CNG4c identified the AFLP4 isolates, probe CNG5b identified the AFLP5 isolates, probe CNG3 identified the AFLP6 isolates, and probe CNG6 identified the AFLP7 isolates. These results show that the Luminex suspension array correctly genotyped all haploid strains (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Results obtained with the Luminex suspension array for all six haploid groups within C. neoformans and C. gattii. Examples of the results obtained with the AFLP1, -2, -4, -5, -6, and -7 genotypic groups are depicted in panels a, b, c, d, e, and f, respectively.

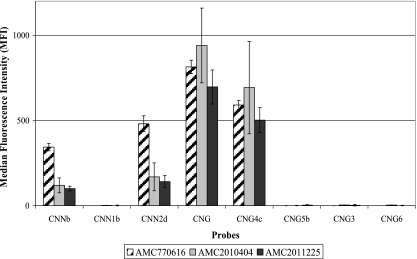

The Luminex suspension array was also used to genotype ten hybrid isolates. Five out of seven serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrid isolates, namely AMC881205I, CDC92-26, Kl#1, Kl#45, and ZG287, were identified as hybrids between the two varieties of C. neoformans by probes CNNb, CNN1b, and CNN2d (Fig. 2a). However, two serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrid isolates, namely AMC890351 and AMC891529, were identified as C. neoformans var. neoformans by probes CNNb and CNN2d (Fig. 2b). The three serotype BD (AFLP8) hybrid isolates were identified as hybrids between C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. gattii AFLP4 by probes CNG, CNG4c, CNNb, and CNN2d (Fig. 3). Interestingly, when the suspension array identified a hybrid isolate, low signal intensities, namely 16% to 53% of an average positive signal, were obtained for probes which identified one of the parental genotypes. The results of the suspension array correlated with the number of clones that were found for each allele. For example, more AFLP4 than AFLP2 IGS1 clones were obtained for the serotype BD hybrid isolates. The Luminex probes gave a similar outcome: the signals for probes CNG and CNG4c, which identify the C. gattii AFLP4 genotype, had normal intensities, i.e., 546 to 940 MFI. The probes which identify C. neoformans var. neoformans (AFLP2), namely CNNb and CNN2d, were positive with MFI values ranging from 119 to 311, but the MFI values that were obtained were only 16% to 19% of an average positive signal (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Results obtained with the Luminex suspension array for all of the serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrids of C. neoformans. Panel a shows five serotype AD hybrids that were identified by three probes, and panel b shows two serotype AD hybrids that were identified by two probes.

FIG. 3.

Results obtained with the Luminex suspension array for the serotype BD (AFLP8) hybrid isolates.

Flow cytometry confirmed that all hybrid isolates were diploid or close to diploid (data not shown). In addition, when a part of the CNLAC1 region was cloned and sequenced, two alleles could be obtained for all hybrid isolates. However, when the IGS1 region was used for cloning and sequencing, two alleles were obtained for five serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrid isolates, namely AMC881205I, CDC92-26, Kl#1, Kl#45, and ZG287, but only one IGS1 allele was found in two serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrid isolates, namely AMC890351 and AMC891529, even though thirty clones were sequenced. All three serotype BD (AFLP8) hybrid isolates possessed two IGS1 alleles. Our results show that all hybrid isolates were diploid or close to diploid, they possessed two CNLAC1 alleles, and most hybrid isolates possessed two IGS1 alleles. All hybrid isolates that possessed two IGS1 alleles, the region on which the Luminex probes are based, could be identified as hybrids. In order to further improve the identification of cryptococcal hybrids, a probe derived from another gene could be included. In a multigene study of thirty-one serotype AD hybrid isolates (AFLP3), five isolates possessed two IGS1 alleles, but twenty-seven isolates had two TEF1α alleles, twenty-six isolates possessed two RPB1 alleles, and twenty-three isolates had two CNLAC1 alleles (M. Bovers, unpublished data). This indicates that CNLAC1, RPB1, and TEF1α are potential regions that could be used to improve the identification of cryptococcal hybrids.

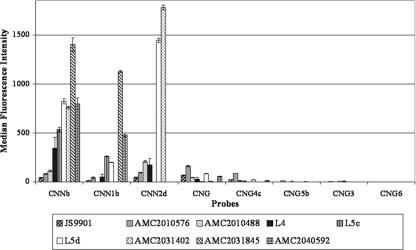

The detection limit of the suspension array was calculated to vary from 4 × 101 to 2 × 103 cells for the different probes (9). In clinical practice, the concentration of cryptococcal cells ranges from 1,000 to 10,000,000 cells per ml of CSF (25). Therefore, the Luminex technology could be a powerful tool for the detection and identification of cryptococcal cells in CSF. CSF specimens from various Dutch and Belgian hospitals that had been stored for up to five years at −80°C were used to test the Luminex suspension array on clinical specimens. Only nine out of twenty CSF specimens obtained from patients with culture-proven cryptococcal meningitis gave an amplicon of the targeted IGS locus. Unfortunately, we do not have additional information, i.e., about the number of (undamaged) cells or about the presence of interfering substances (30) in the samples, to explain why an amplicon could not be obtained. Amplicons of the PCR-positive samples were subsequently used for genotypic identification by the suspension array (Fig. 4), and the results are shown in Table 4. The first two samples that were analyzed, namely JS9901 and AMC2010576, had probe signals that were too low to be considered positive. Optimization of the PCR conditions, i.e., adding 0.2% bovine serum albumin and increasing the amount of DNA and primers in the reaction mix as well as decreasing the temperature of the elongation step to 69°C, improved detection. As a consequence, the infecting agent of the remaining seven samples could successfully be identified at species and genotypic levels, but because no CSF of JS9901 and AMC2010576 remained, the genotype of the infecting agent could not be determined for those two samples. Probes CNNb and CNN1b, with MFI signals ranging from 260 to 1,402, identified the infecting agent in L5c, AMC2040592, and AMC2031845 as C. neoformans var. grubii. Probes CNNb and CNN2d identified the source of infection of AMC2010488, L4, and AMC2031402 as C. neoformans var. neoformans, with MFI signals ranging from 112 to 1,780. Probes CNNb, CNN1b, and CNN2d, with MFI signals ranging from 199 to 1,446, identified the cryptococcal strain responsible for infection of the patient of specimen L5d as a serotype AD (AFLP3) strain of C. neoformans. Interestingly, CSF specimens L5c and L5d were obtained from the same patient, thus suggesting a dual infection by a haploid C. neoformans var. neoformans and a serotype AD (AFLP3) hybrid strain. Our results show that the suspension array is highly specific, as both varieties of C. neoformans (C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans) and a hybrid could be identified in CSF specimens. The clinical applicability of the Luminex suspension array might be improved by optimization of the DNA isolation protocol, as this is one of the critical steps in any molecular detection system (2). In addition, to determine the robustness of the method, fresh clinical specimens for which the amount of cryptococcal cells and the antigen titers are known should be tested and follow-up studies should be performed on samples with false-negative results.

FIG. 4.

Luminex suspension array results for the amplicons obtained from CSF specimens.

In summary, the Luminex suspension array has the potential to become an efficient diagnostic method with high specificity that not only identifies cryptococcal isolates at the species and genotype levels but that also allows identification of hybrid isolates that possess two IGS1 alleles. Furthermore, our results show that the Luminex suspension array is able to identify cryptococci in CSF specimens. Identification in CSF occurs at the species, genotype, and hybrid levels, but optimization of DNA extraction methods is needed before the method is suited for routine use in clinical laboratories.

Acknowledgments

Our special gratitude goes to A. van Belkum (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and K. Lagrou (University Hospital Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) for sending us clinical specimens.

This research was partially funded by National Institutes of Health grant 1-UO1 AI53879-01, the ‘Odo van Vloten fonds’ and the ‘Netherlands-Florida Scholarship Foundation’.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barreto de Oliveira, M. T., T. Boekhout, B. Theelen, F. Hagen, F. A. Baroni, M. S. Lazera, K. B. Lengeler, J. Heitman, I. N. G. Rivera, and C. R. Paula. 2004. Cryptococcus neoformans shows a remarkable genotypic diversity in Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1356-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baums, I. B., K. D. Goodwin, T. Kiesling, D. Wanless, and J. W. Fell. Luminex detection of fecal indicators in river samples, marine recreational water, and beach sand. Mar. Pollut. Bull., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bicanic, T., and T. S. Harrison. 2004. Cryptococcal meningitis. Br. Med. Bull. 72:99-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boekhout, T., B. Theelen, M. Diaz, J. W. Fell, W. C. Hop, E. C. Abeln, F. Dromer, and W. Meyer. 2001. Hybrid genotypes in the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology 147:891-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bovers, M., F. Hagen, E. E. Kuramae, M. R. Diaz, L. Spanjaard, F. Dromer, H. L. Hoogveld, and T. Boekhout. 2006. Unique hybrids between fungal pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. FEMS Yeast Res. 6:599-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cogliati, M., M. Allaria, G. Liberi, A. M. Tortorano, and M. A. Viviani. 2000. Sequence analysis and ploidy determination of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans. J. Mycol. Med. 10:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das, S., T. M. Brown, K. L. Kellar, B. P. Holloway, and C. J. Morrison. 2006. DNA probes for the rapid identification of medically important Candida species using a multianalyte profiling system. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46:244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz, M. R., and J. W. Fell. 2004. High-throughput detection of pathogenic yeasts of the genus Trichosporon. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3696-3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz, M. R., and J. W. Fell. 2005. Use of a suspension array for rapid identification of the varieties and genotypes of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3662-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz, M. R., T. Boekhout, T. Kiesling, and J. W. Fell. 2005. Comparative analysis of the intergenic spacer regions and population structure of the species complex of the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:1129-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz, M. R., T. Boekhout, B. Theelen, M. Bovers, F. J. Cabañes, and J. W. Fell. 2006. Microcoding and flow cytometry as a high-throughput fungal identification system for Malassezia species. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:1197-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz, M. R., T. Boekhout, B. Theelen, and J. W. Fell. 2000. Molecular sequence analyses of the intergenic spacer (IGS) associated with rDNA of the two varieties of the pathogenic yeast, Cryptococcus neoformans. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:535-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunbar, S. A., C. A. Vander Zee, K. G. Oliver, K. L. Karem, and J. W. Jacobson. 2003. Quantitative, multiplexed detection of bacterial pathogens: DNA and protein applications of the Luminex LabMAP system. J. Microbiol. Methods 53:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoang, L. M. N., J. A. Maguire, P. Doyle, M. Fyfe, and D. L. Roscoe. 2004. Cryptococcus neoformans infections at Vancouver hospital and health sciences centre (1997-2002): epidemiology, microbiology and histopathology. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:935-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidd, S. E., F. Hagen, R. L. Tscharke, M. Huynh, K. H. Bartlett, M. Fyfe, L. Macdougall, T. Boekhout, K. J. Kwon-Chung, and W. Meyer. 2004. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:17258-17263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon-Chung, K. J., J. E. Bennett, and J. C. Rhodes. 1982. Taxonomic studies on Filobasidiella species and their anamorphs. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 48:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon-Chung, K. J., T. Boekhout, J. W. Fell, and M. Diaz. 2002. Proposal to conserve the name Cryptococcus gattii against C. hondurianus and C. bacillisporus (Basidiomycota, Hymenomycetes, Tremellomycetidae). Taxon 51:804-806. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and A. Varma. 2006. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 6:574-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latouche, G. N., M. Huynh, T. C. Sorrell, and W. Meyer. 2003. PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the phospholipase B (PLB1) gene for subtyping of Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2080-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lengeler, K. B., G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman. 2001. Serotype AD strains of Cryptococcus neoformans are diploid or aneuploid and are heterozygous at the mating-type locus. Infect. Immun. 69:115-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer, W., A. Castañeda, S. Jackson, M. Huynh, E. Castañeda, and the IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group. 2003. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:189-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirza, S. A., M. Phelan, D. Rimland, E. Graviss, R. Hamill, M. E. Brandt, T. Gardner, M. Sattah, G. P. de Leon, W. Baughman, and R. A. Hajjeh. 2003. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:789-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell, D. H., T. C. Sorrell, A. M. Allworth, C. H. Heath, A. R. McGregor, K. Papanaoum, M. J. Richards, and T. Gottlieb. 1995. Cryptococcal disease of the CNS in immunocompetent hosts: influence of cryptococcal variety on clinical manifestations and outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page, B. T., and C. P. Kurtzman. 2005. Rapid identification of Candida species and other clinically important yeast species by flow cytometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4507-4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perfect, J. R., D. T. Durack, and H. A. Gallis. 1983. Cryptococcemia. Medicine 62:89-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speed, B., and D. Dunt. 1995. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21:28-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephen, C., S. Lester, W. Black, M. Fyfe, and S. Raverty. 2002. Multispecies outbreak of cryptococcosis on southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Can. Vet. J. 43:792-794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka, R., K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 1999. Ploidy of serotype AD strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 40:31-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velegraki, A., V. G. Kiosses, H. Pitsouni, D. Toukas, V. D. Daniilidis, and N. J. Legakis. 2001. First report of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii serotype B from Greece. Med. Mycol. 39:419-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson, I. G. 1997. Inhibition and facilitation of nucleic acid amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3741-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson, W. J., A. M. Erler, S. L. Nasarabadi, E. W. Skowronski, and P. M. Imbro. 2005. A multiplexed PCR-coupled liquid bead array for the simultaneous detection of four biothreat agents. Mol. Cell. Probes 19:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, J., R. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 2000. Multiple gene genealogies reveal recent dispersion and hybridization in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Ecol. 9:1471-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]