Abstract

We review the experience at our institution with galactomannan (GM) testing of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) among solid-organ transplant recipients. Among 81 patients for whom BAL GM testing was ordered (heart, 24; kidney, 22; liver, 19; lung, 16), there were five cases of proven or probable IPA. All five patients had BAL GM of ≥2.1 and survived following antifungal therapy. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for BAL GM testing at a cutoff of ≥1.0 were 100%, 90.8%, 41.7%, and 100%, respectively. The sensitivity of BAL GM testing was better than that of conventional tests such as serum GM or BAL cytology and culture. Moreover, a positive BAL GM test diagnosed IPA several days to 4 weeks before other methods for three patients. Twelve patients had BAL GM of ≥0.5 but no evidence of IPA. Among these, lung transplant recipients accounted for 41.7% (5/12) of the false-positive results, reflecting frequent colonization of airways in this population. Excluding lung transplants, the specificity and positive predictive value for other solid-organ transplants increased to 92.9% and 62.5%, respectively (cutoff, ≥1.0). In conclusion, BAL GM testing facilitated more-rapid diagnoses of IPA and the institution of antifungal therapy among non-lung solid-organ transplant recipients and helped to rule out IPA.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a devastating disease in immunosuppressed patients. The incidence of IPA is roughly 15% among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients and neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies and is generally slightly lower among solid-organ transplant recipients (5, 7, 13, 15, 21). Case fatality rates are as high as 50 to 90% despite aggressive antifungal therapy (5, 11, 13, 21). Prompt diagnoses of IPA improve survival (6, 23), but they are difficult to make due to the inadequacies of conventional diagnostic methods. At present, diagnosis generally depends on the cultivation of Aspergillus spp. from respiratory tract samples or the detection of hyphae within biopsy specimens. These approaches are limited by the insensitivity of cultures and the invasiveness of transbronchial biopsies. Presumptive diagnoses based on the evolution of lesions detected by thoracic computed tomography (CT) scanning facilitate the institution of therapy in the absence of culture or biopsy results (2, 3, 12, 24), but this strategy is limited by low sensitivity and a lack of specificity for IPA compared to other infectious processes (25). Moreover, classic halo and air crescent signs are well described among neutropenic hosts but are less common in solid-organ transplant recipients (9, 21).

Not surprisingly, there is much interest in alternative diagnostic methods that might complement conventional approaches (8). Best studied among these is a commercially available double-sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that detects galactomannan (GM), a cell wall polysaccharide of most Aspergillus and Penicillium species that is released into serum during growth in tissue (Platelia ELISA; Bio-Rad). The overall sensitivity of the serum ELISA is approximately 61% to 71%, with a specificity of 89% to 93% (16). The test performs best among HSCT recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies, populations with the highest incidence of IPA (16). Experience among patients undergoing solid-organ transplantation is much more limited. In studies of lung and liver transplant recipients, the sensitivities of the assay were 30% and 56%, respectively (4, 9), with specificities of 93% to 95% and 87% to 94%, respectively (4, 9, 10).

It has been suggested that the moderate sensitivity and relatively low positive predictive value (PPV) of serum GM testing in diagnosing IPA might be improved by testing bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples (9, 14). Among HSCT recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies, detection of GM within BAL samples added to the sensitivity of both BAL culture and serum GM detection (1, 14, 17-20). While the specificity of BAL GM detection has generally been good (14, 17), high rates of false-positive results were reported in at least one study (22). To date, there have been no studies of BAL GM detection among solid-organ transplant recipients. The objectives of this study were to review our experience with BAL GM detection among solid-organ transplant recipients and to assess the utility of the assay in the diagnosis of IPA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of patients.

We reviewed all cases of solid-organ transplant recipients from the Shands Teaching Hospital at the University of Florida who had BAL fluid tested for GM between September 2004 and September 2006. BAL was performed according to the methods of individual pulmonologists. In general, the bronchus of the lobe in which consolidation was imaged by chest radiograph or chest CT scan was wedged, and 50 ml of 0.9% sterile saline solution at room temperature was instilled with a syringe through the working channel of the bronchoscope. The total volume of saline solution instilled into the lung was typically 150 ml, and 50 to 100 ml of BAL fluid was recovered. The BAL fluid was sent unprocessed on dry ice via overnight mail to MiraVista Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN).

Platelia Aspergillus EIA.

The Platelia Aspergillus enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA) was performed at MiraVista Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturers' procedures. Although the Platelia Aspergillus EIA is not FDA approved for testing of BAL fluid, its accuracy with BAL fluid was validated at MiraVista Diagnostics. First, 100 μl of the Platelia treatment solution was added to 300 μl of the BAL or serum specimen, which was then heated for 4 min in a heat block (Fisher Scientific, Chicago, IL) at 104°C, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Next, 50 μl of the supernatant and 50 μl of the horseradish peroxidase-labeled monoclonal antibody (EBA-2) were incubated in antibody-precoated microplates for 90 min at 37°C. The plates were washed five times, after which they were incubated with 200 μl of substrate chromogen reaction solution for 30 ± 5 min in the dark at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid. Finally, within 30 min of adding the sulfuric acid, the plates were read at an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) with a reference filter of 620/630 nm. An OD index of 0.5 was considered positive. All positive samples were retested and considered positive only if the repeat test was also positive. Tests were performed as samples were received, and results were reported the same day for negative specimens and after confirmation the next day for positive specimens.

Case definitions.

Proven, probable, and possible IPA was defined with modified EORTC-MSG criteria (http://www.doctorfungus.org/lecture/eortc_msg_rev06.htm) and assigned by physician investigators in a blinded fashion. In the event of disagreement, a consensus was reached by the investigators. BAL GM results were not made available to the investigators until the reviews were finished. The results are not included in the definition of IPA.

Definition of positive BAL GM results.

BAL GM results were reported as numerical values to the physicians caring for patients. The physicians made all management decisions. Interpretive cutoff values for positive BAL GM have not been established, but in this study we adopted the 0.5 cutoff proposed for serum testing.

Data analysis.

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for BAL GM testing, serum GM testing, and BAL cytology and culture. The optimal cutoff for BAL GM testing was determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Factors associated with IPA were determined with Fisher's exact test and expressed in two-by-two contingency tables; P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Description of patient population.

Eighty-one solid-organ transplant recipients from our medical center had the Platelia ELISA performed by MiraVista Diagnostics on BAL fluid over a 2-year period (Table 1). BAL was performed for the following reasons: respiratory symptoms (n = 61), fever/sepsis and abnormal imaging study of the chest (n = 17), abnormal chest X-ray findings during a routine clinic visit (n = 2), and routine BAL surveillance following lung transplant (n = 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of enrolled patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) (yr) | 54 (4-79) |

| % Male (no. male/total) | 74.1 (60/81) |

| Type of transplant (%) | |

| Kidney | 27.2 (22/81) |

| Heart | 29.6 (24/81)a |

| Lung | 19.8 (16/81)b |

| Liver | 24.5 (19/81)c |

| Rate of IPA (%) | 6.2 (5/81) |

| No. proven | 2 |

| No. probable | 3 |

| Median time from transplant to BAL (range) | 2.5 yr (2 days-34 yr) |

| Kidney | 4 yr (1 day-34 yr) |

| Heart | 2.5 yr (2 days-20 yr) |

| Lung | 1 yr (1 mo-7 yr) |

| Liver | 1 yr (1 mo-18 yr) |

Four patients received multiple-organ transplants (two heart-lung and two heart-kidney); they are not listed in the lung or kidney group.

One patient received a lung-kidney transplant; he is not listed in the kidney group.

One patient received a liver-pancreas transplant.

Five patients had IPA (liver transplant, 1; heart transplant, 1; kidney transplant, 3) (Table 2). According to the modified EORTC-MSG criteria, two patients were classified as having proven IPA and three as having probable IPA. No patients fulfilled the criteria for possible aspergillosis.

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with IPA

| Patient (age [yr], sex) | Transplant statusa | Reason(s) for BAL | CXR/CT scan | Antibiotic(s) prior to or at the time of BALb | BAL GM resultc | Serum GM resultd | Cytology result | Transbronchial biopsy of BAL fluid result | BAL fluid culture result | Diagnosis | Treatmente | Outcome, follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (54, male) | 3rd liver transplant; 3 wk; Sol (10 mg/day), FK506 | Fever, sepsis | Multifocal consolidations | AmBLC (3 wk), Lvx, Van | 8.83* | 0.07* | ND | ND | No fungus | Proven IPA (disseminated aspergillosis by brain and thyroid biopsies) | Vrc added to AmBLC after BAL result (treated for 1 yr); resection of the brain and thyroid lesions | Survived, 1.2 yr |

| 2 (40, male) | Kidney; 5 yr; Pred (60 mg/day) | Cough, pleurisy, hemoptysis | Multiple bilateral cavities with surrounding ground glass opacities | Tim, Azm | 2.58† | 0.04† | Acute inflammation; no hyphae | Acute inflammation; no hyphae | Negative | Proven IPA (culture of pleural fluid, A. fumigatus) | Vrc (8 mo) | Survived, 2 yr |

| 3 (64, male) | Heart; 2 yr; Siro, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever | Cavity with surrounding infiltrates | Mxf | 2.1 | ND | Inflammation and hyphae | Necrotic tissues with hyphae | Candida sp. | Probable IPA | AmBLC plus Vrc immediately after BAL, then Vrc after GM result (6 mo) | Survived, 10 mo |

| 4 (58, male) | Kidney; 3 mo; ATG, FK506, Myco, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever, chest pain | Multiple bilateral cavities/nodules | Cro, Azm, Sxt | 10.12 | 0.93‡ | Inflammation; hyphae | Acute and chronic inflammation; no hyphae | A. fumigatus, A. flavus | Probable IPA | AmBLC immediately after BAL, then Vrc after GM result (3 mo) | Survived, 1.3 yr |

| 5 (42, male) | 3rd kidney transplant; 5.3 yr; FK506, Myco, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever, cough | Multiple bilateral cavities and nodular densities | None | 3.77 | 0.13 | No hyphae | Focal acute/chronic inflammation; no hyphae | Penicillium sp., A. fumigatus | Probable IPA | Vrc (1.25 yr) | Survived, 1.25 yr |

Transplant status: transplanted organ; time from last transplant to BAL; immunosuppressive regimen. Abbreviations: Sol, methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol); FK506, tacrolimus; Pred, prednisone; Siro, sirolimus; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; Myco, mycophenolate.

Abbreviations: AmBLC, amphotericin B lipid complex; Lvx, levofloxacin; Van, vancomycin; Tim, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid (Timentin); Azm, azithromycin; Mxf, moxifloxacin; Cro, ceftriaxone; Sxt, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Symbols: *, follow-up BAL GM results during antifungal therapy, 7.72 (21 days), 0.19 (5 months), 0.26 (9 months); †, follow-up BAL GM results during antifungal therapy, 0.13 (2 months), 0.23 (9 months).

Symbols: *, follow-up serum GM results over the next 4 days, 0.07, 0.07, 0.06; †, follow-up serum GM results over the next 6 days, 0.44, 0.06, 0.06, 0.12; ‡, follow-up serum GM results during antifungal therapy, 0.11 (4 days), 0.06 (1 month), 0.07 (1 month), 0.07 (2 months). ND, not done.

Abbreviations: Vrc, voriconazole; AmBLC, amphotericin B lipid complex.

Performance of diagnostic tests and radiological studies. (i) BAL GM.

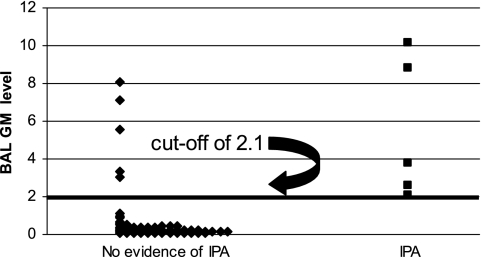

Seventeen patients had at least one BAL GM result of ≥0.5 (12 patients had BAL GM results of ≥1.0) (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1). Only one patient was receiving an agent with antimold activity for prophylaxis at the time of BAL collection (ABLC; 5 mg/kg); this patient had proven IPA and a GM level of 8.83 (patient 1 in Table 2).

TABLE 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients without IPA but with BAL GM results of >0.5

| Patient (age [yr], sex) | Transplant statusa | Reason(s) for BAL | CXR/CT scan | Antibiotic(s) prior to or at the time of BALb | BAL GM result | Serum GM resultc | Cytology result | Transbronchial biopsy of BAL fluid result | BAL fluid culture result | Diagnosis | Treatmentd | Outcome, follow-up period (cause of death) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (57, male) | Heart; 2.5 yr; Pred (10 mg/day), FK506 | Fever, cough, wt loss, diabetic ketoacidosis | Large nodular mass extending to chest wall; mediastinal adenopathy | Fep, Van | 0.55 | 0.1 | No hyphae | Focal lymphocytic inflammation; yeast but no hyphae | C. albicans | Pneumonia due to Rhodococcus equi | No antifungal | Survived, 1.5 yr |

| 2 (40, male) | 3rd liver transplant; 3 wk; Sol (20 mg/day), FK506 | Hypotension, multisystem organ failure | Multiple bilateral nodules | Flc, Fep, Metro | 0.56 | 0.1, 0.33 | No hyphae (+) yeast | ND | C. glabrata | Bacteremia and pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa | AmBLC (2 days), then Vrc (3 wk) (until death) | Died, 3 wk (bowel perforation and multisystem organ failure) |

| 3 (48, female) | Single lung; 5.5 yr; CyA, Aza, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever, shortness of breath, cough | Focal mild consolidation | Sxt, Fep | 0.63 | ND | No hyphae | Mild acute cellular rejection | Candida | Rejection | No antifungal | Survived, 1.3 yr |

| 4 | Bilateral lung; 4 yr; FK506, Siro, Pred (5 mg/day) | Fever, hypoxemia | Ground glass opacification (diffuse) | Sxt | 0.86 | 0.2 | PCP | Interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate | No fungus | Pneumocystis pneumonia | No antifungal | Survived, 4 mo |

| 5 (65, male) | Kidney; 4 yr; CyA, Myco, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever, chills, rigors, weakness | Patchy airspace disease and ground glass opacity (focal) | Fep, Van | 0.96 | 0.06 | No hyphae; normal cells | Mild interstitial edema; no hyphae | No fungus | Community-acquired pneumonia | No antifungal | Survived, 1.1 yr |

| 6 (63, female) | Heart; 1.5 mo; Sol (50 mg/day), FK506 | Septic shock | Consolidation (multifocal) | Fep | 1.09 | 0.11, 0.24 | ND | ND | No fungus | Refractory pulmonary valve endocarditis due to Enterococcus faecalis | Vrc (2.5 days) (until death) | Died, 3 wk (multisystem organ failure and refractory enterococcal bacteremia) |

| 7 (55, male) | Kidney; 10 yr; CyA, Myco, Pred (10 mg/day) | Fever, chills, shortness of breath, weak | Consolidation (focal); hilar adenopathy | None | 1.62, 0.10 (2 days later) | ND | No hyphae | Squamous cell cancer; no hyphae | Penicillium | Lung cancer with postobstructive pneumonia | No antifungal | Survived, 4 mo |

| 8 (51, female) | Bilateral lung; 5 wk; FK506, Aza, Pred (10 mg/day) | Bronchial stenosis due to lung reperfusion lung injury | Focal consolidation | Van, Gat, Dapsone | 3.04, 1.5 (7 days later) | ND | Acute inflammation cells; hyphae | ND | A. terreus | Bacterial pneumonia | Inhaled AmB (3 days) (to “eradicate colonization”) | Survived, 1.4 yr |

| 9 (55, male) | Heart; 3 wk; OKT3, FK506, Myco, Sol (100 mg/day) | Post-transplant sepsis | Extensive focal consolidation; pleural effusion | Fep, Van | 3.35, 0.12 (2 days later), 0.13 (3 days later), 0.10 (4 days later) | 0.12, 0.13, 0.10 | ND | ND | No fungus | Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae | Vrc (2.25 mo) (until death) | Died, 2.25 mo (sepsis due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter; cardiopulmonary arrest) |

| 10 (60, male) | Heart; 2 mo; CyA, Myco, Sol (150 mg/day) | Fever, cough, hemoptysis | Focal consolidation with reticulonodular component | Fep, Van, Azm, Metro, Sxt | 5.57 | 0.11 | No hyphae; acid-fast organisms | ND | No fungus | Pneumonia due to Nocardia asteroides | Vrc (7 days) (until death) | Died, 8 days (multisystem organ failure, sepsis) |

| 11 (59, female) | Single lung; 2.5 mo; FK506, Aza, Pred (20 mg) | Fever, cough, chills | No infiltrates (X-ray only) | Sxt | 7.14 | ND | Acute inflammation; hyphae | Acute pneumonia; no hyphae | A. flavus, A. niger | Pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa; mild rejection | No antifungal | Survived, 1.3 yr |

| 12 (33, female) | Single lung; 2 yr; FK506, Pred (10 mg/day) | Shortness of breath, nausea | Ground glass consolidation (focal) and pleural effusion | Sxt | 8.1 | ND | Many macrophages; (+) hyphae | Mild lymphocytic bronchitis with unattached hyphae | A. flavus | MRSA pneumonia | Itraconazole (1 wk) | Died, 2 mo (disseminated MRSA infection [autopsy]) |

Transplant status: transplanted organ; time from last transplant to BAL; immunosuppressive regimen. Abbreviations: Cya, cyclosporin A; Aza, azathioprine; OKT3, muromonab-CD3; Sol, methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol); FK506, tacrolimus; Pred, prednisone; Siro, sirolimus; Myco, mycophenolate.

Abbreviations: Fep, cefepime; Van, vancomycin; Azm, azithromycin; Metro, metronidazole; Gat, gatifloxacin; Sxt, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

ND, not done.

Abbreviations: Vrc, voriconazole; AmBLC, amphotericin B lipid complex.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of BAL GM results.

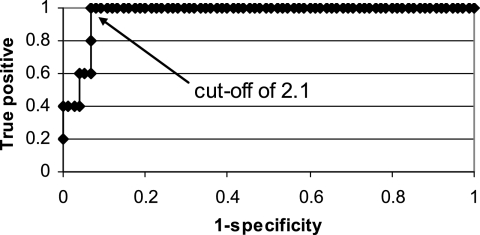

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of BAL GM testing at various interpretive cutoffs are presented in Table 4. All five patients with IPA had BAL GM levels of ≥2.1 (range, 2.1 to 10.12). A cutoff of ≥0.5 yielded sensitivity and NPV of 100%, with relatively low specificity and PPV (Table 4). Increasing the cutoff to ≥1 improved the specificity (Table 4). As shown in the ROC curve (Fig. 2), further increasing the cutoff values to 1.5 and 2 improved specificity slightly.

TABLE 4.

Performance of diagnostic tests

| Test | % (no. with indicated result/total)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| BAL GM | ||||

| Cutoff, ≥0.5 | 100 (5/5) | 84.2 (64/76) | 29.4 (5/17) | 100 (64/64) |

| Cutoff, ≥1 | 100 (5/5) | 90.8 (69/76) | 41.7 (5/12) | 100 (69/69) |

| Cutoff, ≥1.5 | 100 (5/5) | 92.1 (70/76) | 45.4 (5/11) | 100 (70/70) |

| Cutoff, ≥2 | 100 (5/5) | 93.4 (71/76) | 50 (5/10) | 100 (71/71) |

| Cutoff, ≥2.5 | 80 (4/5) | 93.4 (71/76) | 44.4 (4/9) | 98.6 (71/72) |

| Serum GM (single value, ≥0.5) | 25 (1/4) | 97 (33/34) | 50 (1/2) | 91.7 (33/36) |

| Positive cytology | 50 (2/4) | 93.2 (69/74) | 28.6 (2/7) | 97.2 (69/71) |

| Positive culture for Aspergillus sp. | 40 (2/5) | 93.4 (71/76) | 28.6 (2/7) | 95.9 (71/74) |

| Positive cytology or culture | 60 (3/5) | 90.8 (69/76) | 30.0 (3/10) | 97.2 (69/71) |

| Cavity seen on chest CT | 80 (4/5) | 100 (73/73) | 100 (4/4) | 98.7 (73/74) |

FIG. 2.

ROC curve.

(ii) BAL cytology and culture and serum GM testing.

BAL fluid was sent for cytology from 78 patients (including 4 of 5 patients with IPA) and for culture from all patients. The sensitivities of cytology and culture were 50% and 40%, respectively (Table 4).

Serum GM testing was ordered for 38 patients, including 4 of the 5 patients with IPA. In each case, serum and BAL GM samples were collected within 3 days of one another. Only one patient with IPA demonstrated a serum GM level of ≥0.5 (0.93; sensitivity of serum GM testing, 25%). Moreover, two patients with IPA had serum GM levels of ≥4 that were negative within a week of a positive BAL GM test (patients 1 and 2 in Table 2). The specificity, PPV, and NPV of serum GM testing (with a positive test defined as a single value of ≥0.5) are compared to those of BAL GM testing, cytology, and culture in Table 4. The concordance between serum and BAL GM levels is summarized in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Concordance between serum and BAL GM levels

| Serum GM level | Total no. of patients (no. with IPA)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| BAL GM, <0.5 | BAL GM, 0.5-0.9 | BAL GM, ≥1.0 | |

| <0.5 | 26 (0) | 4 (0) | 6 (3) |

| ≥0.5 | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (1) |

(iii) Test results and radiological findings significantly associated with IPA.

The following test results and radiological findings were more closely associated with IPA than with alternative diagnoses (Table 6): (i) BAL GM result of ≥1.0, (ii) cavitary lung lesions upon chest CT scan, (iii) BAL cytology consistent with mold, and (iv) positive BAL culture for Aspergillus or cytology for mold. Chest X-ray and/or CT scan were performed for 78 patients at our medical center. We did not find any association between IPA and serum GM levels or nodules/nodular infiltrates without cavities. Indeed, nodular lesions were described in a range of diagnoses, including bacterial pneumonia (n = 6), pulmonary histoplasmosis (n = 2), pulmonary nocardiosis (n = 2), disseminated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or enterococcal infection (n = 2), Rhodococcus pneumonia (n = 1), cytomegalovirus pneumonitis (n = 1), lung cancer (n = 1), and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (n = 1). Two patients with IPA had nodular lesions and cavities. An air crescent sign was detected in only one patient, who was found to have pulmonary nocardiosis but not IPA.

TABLE 6.

Factors associated with IPA

| Factor | % of patients (no./total)

|

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With IPA | Without IPA | ||

| BAL GM level, ≥1.0 | 100 (5/5) | 9.2 (7/76) | <0.0001 |

| Cytology positive for hyphal elements | 50 (2/4) | 6.8 (5/74) | 0.04 |

| Culture positive for Aspergillus sp. | 40 (2/5) | 6.6 (5/76) | 0.06 |

| Positive cytology or culture | 60 (3/5) | 9.2 (7/76) | 0.01 |

| Cavitary lesions observed on chest CT or X-ray | 80 (4/5) | 0 (0/73) | <0.0001 |

| Nodules or nodular lesions on chest CT or X-ray (without cavity) | 0 (0/5) | 21.9 (16/73) | 0.58 (NS) |

| Serum GM level, ≥0.5 | 20 (1/5) | 3 (1/33) | 0.25 (NS) |

NS, not significant.

Not surprisingly, BAL cultures positive for either Aspergillus sp. or Penicillium sp. were significantly associated with BAL GM results of ≥1.0 (P = 0.003). The presence of hyphal elements upon cytology was also associated with BAL GM results of ≥1.0 (P = 0.001). These associations were noted whether the elevated GM level represented a true- or false-positive result.

Impact of BAL GM on the time to diagnosis of IPA.

For two patients with proven or probable IPA (patients 1 and 2 in Table 2), BAL GM was the first positive test for the disease, occurring 1 and 4 weeks before a positive brain biopsy and pleural fluid culture, respectively. In a third patient (patient 5 in Table 2), the BAL culture revealed both A. fumigatus and Penicillium. Since cultures took several days to grow, however, a positive BAL GM shortened the time to diagnosis and the institution of antifungal therapy. In the remaining two patients with IPA, BAL GM was positive and cytology revealed hyphae within 2 days.

DISCUSSION

The most notable finding of our study was that BAL GM testing added to the sensitivity of conventional methods for the diagnosis of IPA while maintaining excellent specificity (90.8% at a cutoff of ≥1.0). The sensitivity of BAL GM testing was 100%, compared to 50%, 40%, and 25% for cytology, culture, and transbronchial biopsy results, respectively, and 25% for serum GM levels of ≥0.5. For three patients (patients 1, 2, and 5 in Table 2), a positive BAL GM result suggested IPA several days to 4 weeks before a diagnosis was available by other methods. Conversely, we found that a negative BAL GM effectively excluded the diagnosis of IPA (NPV, 100% [at a cutoff of ≥1.0]). Moreover, in the two cases of IPA in which serial bronchoscopies were performed, clinical responses to antifungal therapy were associated with decreases in BAL GM levels to <0.5. In our experience, therefore, BAL GM testing was a useful adjunct to conventional tests in diagnosing, excluding, and monitoring IPA among solid-organ transplant recipients.

The major shortcoming of the test was false-positive results, as was also reported in at least one previous study of patients with hematologic malignancies (22). In our series, the PPV was 41.7% with a cutoff of ≥1.0 and 29.4% with a cutoff of ≥0.5. None of the false-positive results occurred among patients receiving piperacillin-tazobactam or other antimicrobials previously linked to false-positive serum results. Rather, both true- and false-positive BAL GM results were significantly associated with cultures that yielded Aspergillus or Penicillium sp. and/or cytology that revealed hyphal elements. Moreover, the extent to which a GM level was positive did not differ for patients with and without IPA. These observations imply that BAL GM reflected the presence of molds but did not distinguish between invasive disease and colonization.

The performance of BAL GM testing among our lung transplant recipients merits particular consideration for two reasons. First, there were no cases of proven or probable IPA, fungal tracheobronchitis, or bronchial anastomotic infections among patients receiving lung transplants, which precluded any assessment of the diagnostic utility of the test in this population. Second, lung transplant recipients accounted for almost half of the false-positive test results (41.7% [5/12] at a cutoff of ≥0.5 and 42.9% [3/7] at a cutoff of ≥1.0). The high rate of false positives is not surprising. While aspergillosis has been reported for about 6% of patients receiving lung transplants, Aspergillus species can be detected in cultures of airway samples from 25% to 30% of patients (21). Indeed, BAL cultures were positive for Aspergillus in 3 of the 16 lung transplant recipients in this study, all of whom had extremely high GM levels (8.1, 7.14, and 3.04). If we exclude the lung transplant recipients from our analysis, the specificity and PPV among patients receiving other solid-organ transplants increase to 92.9% and 62.5%, respectively (cutoff, ≥1.0).

Based on our data, we cannot conclusively define interpretive criteria for BAL GM testing. In part, this is due to the relatively small sample size and the low number of IPA cases in our study. In addition, the distribution of data limited our ability to draw conclusions about cutoffs in the range of 1.0 to 2.0; all five proven or probable cases were associated with levels of ≥2.1, but only two false-positive cases exhibited levels between 1.0 and 2.0. As the cutoff was increased from 1.0 to 2.0, therefore, the sensitivity did not differ and the specificity improved minimally (Fig. 2). Increasing the cutoff from ≥0.5 to ≥1.0, on the other hand, was associated with more-dramatic improvements in test performance and the elimination of five false-positive cases.

Because bronchoscopy is commonly utilized in the evaluation of solid-organ transplant recipients with respiratory symptoms and/or abnormal findings in imaging studies, BAL GM testing is easy to incorporate into standard clinical practices. In addition to making more-rapid diagnoses, facilitating the prompt institution of antifungal therapy, and helping to rule out IPA, BAL GM testing might also lessen the need for invasive procedures such as tissue biopsy to establish definitive diagnoses. Despite the test's appeal, potential obstacles to its successful widespread use include the lack of standardized methods for collecting BAL fluid and uncertainties about the causes of false-positive results and the impact of antifungal agents on the sensitivity of the test. Clearly, issues such as optimal methods, interpretive criteria, and the most rational use of BAL GM testing in widespread clinical practice merit assessment in well-designed prospective studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Florida Mycology Research Unit (NIH grant PO1 AI061537-01 to M.H.N., C.J.C., and J.R.W.). L.J.W. is the President and Director of MiraVista Diagnostics, which performs BAL GM testing as a commercial reference service.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker, M. J., S. de Marie, D. Willemse, H. A. Verbrugh, and I. A. Bakker-Woudenberg. 2000. Quantitative galactomannan detection is superior to PCR in diagnosing and monitoring invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in an experimental rat model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1434-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caillot, D., O. Casasnovas, A. Bernard, J. F. Couaillier, C. Durand, B. Cuisenier, E. Solary, F. Piard, T. Petrella, A. Bonnin, G. Couillault, M. Dumas, and H. Guy. 1997. Improved management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients using early thoracic computed tomographic scan and surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 15:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caillot, D., J. F. Couaillier, A. Bernard, O. Casasnovas, D. W. Denning, L. Mannone, J. Lopez, G. Couillault, F. Piard, O. Vagner, and H. Guy. 2001. Increasing volume and changing characteristics of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis on sequential thoracic computed tomography scans in patients with neutropenia. J. Clin. Oncol. 19:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortun, J., P. Martin-Davila, M. E. Alvarez, A. Sanchez-Sousa, C. Quereda, E. Navas, R. Barcena, E. Vicente, A. Candelas, A. Honrubia, J. Nuno, V. Pintado, S. Moreno, and Ramon y Cajal Hospital's Liver Transplant Group. 2001. Aspergillus antigenemia sandwich-enzyme immunoassay test as a serodiagnostic method for invasive aspergillosis in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 71:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda, T., M. Boeckh, R. A. Carter, B. M. Sandmaier, M. B. Maris, D. G. Maloney, P. J. Martin, R. F. Storb, and K. A. Marr. 2003. Risks and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood 102:827-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene, R. E., H. T. Schlamm, J. W. Oestmann, P. Stark, C. Durand, O. Lortholary, J. R. Wingard, R. Herbrecht, P. Ribaud, T. F. Patterson, P. F. Troke, D. W. Denning, J. E. Bennett, B. E. de Pauw, and R. H. Rubin. 2007. Imaging findings in acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical significance of the halo sign. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:373-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grow, W. B., J. S. Moreb, D. Roque, K. Manion, H. Leather, V. Reddy, S. A. Khan, K. J. Finiewicz, H. Nguyen, C. J. Clancy, P. S. Mehta, and J. R. Wingard. 2002. Late onset of invasive aspergillus infection in bone marrow transplant patients at a university hospital. Bone Marrow Transplant. 29:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hope, W. W., T. J. Walsh, and D. W. Denning. 2005. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:609-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husain, S., E. J. Kwak, A. Obman, M. M. Wagener, S. Kusne, J. E. Stout, K. R. McCurry, and N. Singh. 2004. Prospective assessment of Platelia Aspergillus galactomannan antigen for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 4:796-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwak, E. J., S. Husain, A. Obman, L. Meinke, J. Stout, S. Kusne, M. M. Wagener, and N. Singh. 2004. Efficacy of galactomannan antigen in the Platelia Aspergillus enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in liver transplant recipients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:435-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin, S. J., J. Schranz, and S. M. Teutsch. 2001. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:358-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maertens, J., K. Theunissen, G. Verhoef, J. Verschakelen, K. Lagrou, E. Verbeken, A. Wilmer, J. Verhaegen, M. Boogaerts, and J. Van Eldere. 2005. Galactomannan and computed tomography-based preemptive antifungal therapy in neutropenic patients at high risk for invasive fungal infection: a prospective feasibility study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1242-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marr, K. A., R. A. Carter, F. Crippa, A. Wald, and L. Corey. 2002. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musher, B., D. Fredricks, W. Leisenring, S. A. Balajee, C. Smith, and K. A. Marr. 2004. Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme immunoassay and quantitative PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5517-5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson, T. F., W. R. Kirkpatrick, M. White, J. W. Hiemenz, J. R. Wingard, B. Dupont, M. G. Rinaldi, D. A. Stevens, and J. R. Graybill. 2000. Invasive aspergillosis. Disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 79:250-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeiffer, C. D., J. P. Fine, and N. Safdar. 2006. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis using a galactomannan assay: a meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:1417-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salonen, J., O. P. Lehtonen, M. R. Terasjarvi, and J. Nikoskelainen. 2000. Aspergillus antigen in serum, urine and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens of neutropenic patients in relation to clinical outcome. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 32:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanguinetti, M., B. Posteraro, L. Pagano, G. Pagliari, L. Fianchi, L. Mele, M. La Sorda, A. Franco, and G. Fadda. 2003. Comparison of real-time PCR, conventional PCR, and galactomannan antigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from hematology patients for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3922-3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seyfarth, H. J., P. Nenoff, J. Winkler, R. Krahl, U. F. Haustein, and J. Schauer. 2001. Aspergillus detection in bronchoscopically acquired material. Significance and interpretation. Mycoses 44:356-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siemann, M., and M. Koch-Dorfler. 2001. The Platelia Aspergillus ELISA in diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillus (IPA). Mycoses 44:266-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh, N., and D. L. Paterson. 2005. Aspergillus infections in transplant recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:44-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verweij, P. E., J. P. Latge, and A. J. Rijs. 1995. Comparison of antigen detection and PCR assay using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients receiving treatment for hematological malignancies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:150-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Eiff, M., N. Roos, R. Schulten, M. Hesse, M. Zuhlsdorf, and J. van de Loo. 1995. Pulmonary aspergillosis: early diagnosis improves survival. Respiration 62:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisser, M., C. Rausch, A. Droll, M. Simcock, P. Sendi, I. Steffen, C. Buitrago, S. Sonnet, A. Gratwohl, J. Passweg, and U. Fluckiger. 2005. Galactomannan does not precede major signs on a pulmonary computerized tomographic scan suggestive of invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematological malignancies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1143-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Won, H. J., K. S. Lee, J. E. Cheon, J. H. Hwang, T. S. Kim, H. G. Lee, and J. Han. 1998. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: prediction at thin-section CT in patients with neutropenia—a prospective study. Radiology 208:777-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]