Abstract

Three groups of previously unknown gram-positive, anaerobic, coccus-shaped bacteria were characterized using phenotypic and molecular taxonomic methods. Phenotypic and genotypic data demonstrate that these organisms are distinct, and each group represents a previously unknown subline within Clostridium cluster XIII. Two groups are most closely related to Peptoniphilus harei in the genus Peptoniphilus, and the other group is most closely related to Anaerococcus lactolyticus in the genus Anaerococcus. Based on the findings, three novel species, Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov., Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov., and Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov., are proposed. The type strains of Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov., Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov., and Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov. are WAL 10418T (= CCUG 53341T = ATCC BAA-1383T), WAL 12922T (= CCUG 53342T = ATCC BAA-1384T), and WAL 17230T (= CCUG 53340T = ATCC BAA-1385T), respectively.

Gram-positive anaerobic cocci (GPAC) originally classified in the genus Peptostreptococcus are part of the commensal flora in humans and animals and are commonly associated with a variety of human infections (5, 13). Although GPAC are isolated from approximately one-quarter of all infections involving anaerobic bacteria, studies of the significance of isolates of GPAC have been hindered by an inadequate taxonomy and the lack of a valid identification scheme. The taxonomy of the former genus Peptostreptococcus is currently under revision. Recent 16S rRNA sequence data have showed that the genus Peptostreptococcus is very heterogeneous (8). Two proposals have restricted the genus Peptostreptococcus to Peptostreptococcus anaerobius (15) and placed Peptostreptococcus magnus and Peptostreptococcus micros in two new genera, Finegoldia and Micromonas, respectively (14). However, the name Micromonas is illegitimate because of precedence of a microalga, Micromonas; recently, this organism has been reclassified as Parvimonas micra (20). Ezaki et al. (4) proposed three new genera, Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, and Gallicola. The classification of the GPAC has not been sound and has been confused by many loosely defined taxa. Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus and Anaerococcus prevotii, the two butyrate-producing species commonly reported from human pathological material, have long been recognized as genetically heterogeneous (8). Furthermore, evidence suggests that several clinically important species still await formal description (9, 11). Further studies of the classification of these organisms are needed.

Systematic description of new bacterial species recovered from patients may contribute to the description of emerging infections. Therefore, efforts should be made to report possible novel species, even if only very few strains have been isolated. The strains should be deposited in international collections, and the sequence should be accessible through public databases. This will allow further definition of their clinical significance. In another study developing a biochemical scheme for accurate identification of GPAC using 16S rRNA gene sequencing as a standard (18), we found three groups (groups I, II, and III) of unknown clinical isolates of GPAC which were obtained from clinical specimens of human origin. In this paper, we report on the characterization of these three groups of bacteria. Phenotypically and phylogenetically, the closest validly described species to the unknown bacteria in groups I and II is Peptoniphilus harei (approximately 97.0% and 93.0% sequence similarity, respectively), and the closest validly described species to the unknown bacterium in group III is Anaerococcus lactolyticus (approximately 96.5% sequence similarity). Based on the phenotypic and phylogenetic findings presented here, three novel species, Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov. (group I), Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov. (group II), and Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov. (group III), are proposed. In addition, we also describe the phenotypic tests useful in distinguishing between the various organisms mentioned above.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Altogether, 16 unknown GPAC strains from human clinical specimens (six of group I, four of group II, and six of group III), 14 clinical isolates of GPAC species for comparison (10 of P. harei and two each of P. asaccharolyticus and A. lactolyticus), and 13 reference strains of GPAC were included in the present study (Table 1). Clinical isolates were identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing in our laboratory. Information on the nature of the infections involving the three new taxa was obtained from patient records.

TABLE 1.

Clinical isolates and reference strains used in this study

| Species | Strain(s) | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|

| P. gorbachii (group I) | CCUG 53341T | 1 |

| P. gorbachii | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| P. olsenii (group II) | CCUG 53342T | 1 |

| P. olsenii | Clinical isolates | 3 |

| A. murdochii (group III) | CCUG 53340T | 1 |

| A. murdochii | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| Anaerococcus hydrogenalis | CCUG 49630T | 1 |

| A. lactolyticus | CCUG 31351T | 1 |

| A. lactolyticus | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Anaerococcus octavius | CCUG 38493T | 1 |

| A. prevotii | CCUG 41932T | 1 |

| Anaerococcus tetradius | CCUG 46590T | 1 |

| Anaerococcus vaginalis | CCUG 31349T | 1 |

| P. asaccharolyticus | CCUG 9988T | 1 |

| P. asaccharolyticus | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| P. harei | CCUG 38491T | 1 |

| P. harei Ia | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| P. harei IIb | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| Peptoniphilus ivorii | CCUG 38492T | 1 |

| Peptoniphilus lacrimalis | CCUG 31350T | 1 |

| F. magna | CCUG 17636T | 1 |

| P. micros | CCUG 46357T | 1 |

| P. anaerobius | CCUG 7835T | 1 |

P. harei I strains share >99.5% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with the type strain of P. harei.

P. harei II strains share 98.6% sequence similarity with the type strain of P. harei; they were phenotypically identified as P. asaccharolyticus but shared only low 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with the type strain of P. asaccharolyticus.

All the strains were cultivated on brucella blood agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood, hemin, and vitamin K1 and incubated at 37°C under N2 (86%), H2 (7%), and CO2 (7%) gas phase.

Biochemical characterization.

The strains were characterized biochemically by using a combination of conventional tests as described in the Wadsworth-KTL Anaerobic Bacteriology Manual (7) and the commercially available biochemical kit Rapid ID 32A (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The commercial biochemical kit was used per the manufacturer's instructions, and the results were graded using a color chart supplied by the manufacturer. All biochemical tests were performed in duplicate. Glucose fermentation tests were performed using prereduced, anaerobically sterilized peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth tubes (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA). The strains were grown in peptone-yeast extract broth and peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA) for metabolic end product (short-chain volatile and nonvolatile fatty acids) analysis by gas-liquid chromatography (7).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility studies were done using various antimicrobial agents which were selected either as representatives of a class of compounds or as drugs for which MICs for quality control strains were published, by means of the CLSI (formerly NCCLS)-approved Wadsworth plate dilution method (16).

16S rRNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR using universal primers 8UA (positions 8 to 28, Escherichia coli numbering) and 1485B (positions 1485 to 1507) as described previously (17). The amplified product was purified by using the QIAamp PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA), and both strands of the PCR products were directly sequenced with an ABI 3100 Avant Genetic System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The closest known relatives of the new isolates were determined by performing database searches using BLAST software (1). Almost-full-length sequences of the 16S rRNA gene sequences (>1,400 nucleotides) of the unidentified bacteria and of closely related bacteria were aligned using CLUSTAL-W. A phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using PAUP* 4.0 DNA analysis software (Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA). The stability of the groupings was estimated by bootstrap analysis (1,000 replications) using the same program.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA sequences of strains WAL 10418T, WAL 12922T, and WAL 17230T have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers DQ 911241, DQ 911242, and DQ 911243, respectively.

RESULTS

Clinical information on the unknown bacterial strains. (i) Group I.

Six strains of group I were isolated from six subjects; records were available on five of these. All five subjects had diabetes mellitus, three with peripheral vascular disease, one with diabetic neuropathy, and one with venous stasis ulcers, and one had multiple-substance abuse and trauma to an extremity. One patient had dry (circulatory) gangrene with superficial infection; two had cellulitis, one with abscess formation and one with underlying osteomyelitis; and the other two had infected diabetic foot ulcers, one with osteomyelitis. None of the patients had bacteremia. In two patients, the group I unknown bacterium was present in moderate numbers with numerous facultative organisms also present. The other three patients had numerous colonies of the group I unknown bacterium but also numerous colonies of two to three other anaerobes and one to three facultative bacteria. In summary, the infections were of mild to moderate severity and the specific role of the group I unknown bacterium could not be determined.

(ii) Group II.

There were four patients with the group II unknown bacterium. One specimen was bone with osteomyelitis from a diabetic patient with peripheral vascular disease; this yielded three colonies each of the unknown bacterium and a non-spore-forming gram-positive anaerobic rod as well as one colony of Staphylococcus aureus. A second specimen was from a low-grade infection of a leg with dry gangrene in a patient with severe peripheral vascular disease without diabetes mellitus; this yielded a few colonies each of the unknown bacterium and two other anaerobes, as well as moderate numbers of Proteus mirabilis. A third patient had a diabetic foot ulcer with purulent infection; in this patient, there were moderate numbers of the unknown bacterium but numerous colonies of Finegoldia magna, S. aureus, and lactose-positive and -negative gram-negative facultative rods. The final patient had a toe infection which yielded numerous colonies of the unknown bacterium but also numerous colonies of P. asaccharolyticus and F. magna. In summary, these infections were all low grade in severity and the group II unknown bacterium did not play a major role.

(iii) Group III.

There were six patients with the group III unknown bacterium. Three of these subjects were diabetic, two with neuropathy and one with advanced peripheral vascular disease. One had a foot ulcer with osteomyelitis; this subject's culture grew moderate numbers of the unknown bacterium and a few S. aureus bacteria. A second patient had an infected necrotic foot ulcer which grew numerous colonies of the group III unknown bacterium, Prevotella dentalis, and a Porphyromonas species as well as moderate numbers of F. magna and an alpha-hemolytic facultative streptococcus. The third diabetic patient had an infected plantar ulcer which grew moderate numbers of the group III unknown bacterium, a Prevotella sp. strain, and a Veillonella strain but numerous colonies of S. aureus, a group G streptococcus, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and moderate numbers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A fourth patient had a chronic sternal wound infection following coronary artery bypass grafting; this grew moderate numbers of the unknown bacterium and P. asaccharolyticus. A fifth patient had laryngeal carcinoma with a severe soft-tissue infection of the neck. This patient's culture yielded numerous colonies of the unknown bacterium but also numerous colonies of Bacteroides fragilis, Clostridium perfringens, F. magna, a facultative diphtheroid-like organism, and Enterococcus avium as well as moderate numbers of Prevotella spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The final patient had an abscess of the right thumb following earlier trauma. Culture of the abscess contents yielded numerous colonies of the unknown bacterium, Peptostreptoccus anaerobius, F. magna, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas spp., E. coli, Citrobacter diversus, and Morganella morganii. The role of this organism in most of the infections described is uncertain because of the mixed cultures.

Phenotypic characterization.

All the unknown organisms were found to be gram-positive, coccal organisms. Typical cells of all groups were ≥0.7 μm. Colonies on brucella blood agar plates at 5 days showed differences: strains of group I produced gray, flat or low convex, circular, entire, opaque colonies with a diameter of 1 to 2 mm; strains of group II produced gray, convex, circular, entire, opaque colonies, 2 to 3 mm with a whiter central peak, a colony type seen with the type strain of P. asaccharolyticus; the strains of group III produced gray, flat or low convex, entire, circular, often matt colonies, 1 to 2 mm with whiter centers. They all grew well anaerobically, but no growth occurred following subculture in air or in atmospheres of 2% or 6% O2. Most of the strains were sensitive to the kanamycin (1,000 μg) and vancomycin (5 μg) special potency disks, except for two strains in group III which showed resistance to the kanamycin disk; all the strains in groups I and III were resistant to the colistin sulfate (10 μg) special potency disk, but strains of group II were sensitive.

All strains were catalase, coagulase, urease, and nitrate negative. With the spot indole test, strains of groups I and II were variable and those of group III were negative. Strains of groups I and II were all asaccharolytic; they did not produce acid from glucose while all strains of group III produced acid from glucose. By the Rapid ID 32A test, all isolates of the same group produced similar profiles. For strains of groups I and II, positive reactions were obtained for arginine arylamidase, phenylalanine arylamidase (strong or weak), leucine arylamidase, tyrosine arylamidase, glycine arylamidase, histidine arylamidase, and serine arylamidase. Indole test results were variable for both groups. The glutamyl glutamic acid arylamidase test was positive for isolates of group I but was negative for group II. In contrast, alkaline phosphatase, alanine arylamidase, and leucyl glycine arylamidase (strong or weak) tests were positive for group II but were negative for group I. All the other tests were negative. For strains of group III, positive reactions were obtained for arginine dihydrolase, β-galactosidase, alkaline phosphatase, arginine arylamidase, glycine arylamidase (strong or weak), histidine arylamidase (strong or weak), leucine arylamidase, and acid pyroglutamic arylamidase. β-Glucosidase, leucyl glycine arylamidase, alanine arylamidase, and serine arylamidase results were variable. Mannose was fermented, but not raffinose, when tested by the Rapid ID 32A system. All the other tests were negative. The key characteristics for identification and differentiation of these bacteria from each other and the other GPAC are shown in Table 3. In peptone-yeast extract broth and peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth, major amounts of acetic acid, moderate amounts of butyric acid, and trace amounts of propionic acid were produced by all isolates of groups I and II and major amounts of butyric acid and acetic acid were produced by all isolates of group III.

TABLE 3.

Key distinguishing characteristics of novel species and other GPAC speciesa

| Species | SPS resultb | Result for enzymec:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucosed | Urease | β-Gur | β-Gal | ArgA | PyrA | SerA | GGA | ||

| P. gorbachii | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| P. olsenii | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| P. asaccharolyticus | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| P. harei | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Peptoniphilus ivorii | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Peptoniphilus lacrimalis | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| A. murdochii | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | v | − |

| Anaerococcus hydrogenalis | + | + | − | − | − | − | W | − | − |

| A. lactolyticus | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | v | − |

| Anaerococcus octavius | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| A. prevotii | + | − | v | + | v | + | + | +/w | − |

| Anaerococcus tetradius | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | +/w |

| Anaerococcus vaginalis | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | v | − |

| F. magna | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | +/w | − |

| P. micros | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | +/w |

| P. anaerobius | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Peptostreptococcus stomatis | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Data were mainly from this study and our previously unpublished data (18). All the enzymatic tests were done using the Rapid ID 32A system (API bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Abbreviations: SPS, sodium polyanethol sulfonate; β-Gur, β-glucuronidase; β-Gal, β-galactosidase; ArgA, arginine arylamidase; PyrA, pyroglutamyl acid arginine arylamidase; SerA, serine arginine arylamidase; GGA, glutamyl glutamic acid arginine arylamidase.

The sodium polyanethol sulfonate test was done using sodium polyanethol sulfonate disks (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA). +, no zone or zone of inhibition of <12 mm; −, zone of inhibition of ≥12 mm.

Symbols: −, >90% negative; w, weakly positive; +, >90% positive; v, variable.

Glucose fermentation tests were performed using prereduced, anaerobically sterilized peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth tubes (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA). A pH of ≤<5.5 in the prereduced, anaerobically sterilized tubes was interpreted as positive, a pH of 5.6 to 5.8 was interpreted as weakly positive, and a pH of ≥5.9 was interpreted as negative fermentation.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Agar dilution tests showed that all the strains were susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), cefazolin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), clindamycin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), imipenem (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml), metronidazole (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml), and vancomycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml), except for two strains in group I and one strain in group III which were resistant to clindamycin (MIC, ≥64 μg/ml), and one strain in group I and three strains in group III which showed either intermediate susceptibility or resistance to penicillin (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of the clinical isolates of the three novel speciesa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of drugc:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin-sulbactamb | Cefazolin | Cefoxitin | Clindamycin | Imipenem | Metronidazole | Penicillin | Vancomycin | |

| Group I | ||||||||

| WAL 10418 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.062 | 4 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 13892 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | 128 | ≤0.062 | 0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 16189 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.062 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 17055 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.062 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 17412 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 0.5 | 64 | ≤0.062 | 4 | 1 | ≤1 |

| WAL 17893 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | 1 | ≤0.062 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| Group II | ||||||||

| WAL 12922 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.062 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 12378 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.062 | 0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 12949 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | 1 | ≤0.062 | 0.25 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| WAL 13271 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤0.12 | 1 | ≤0.062 | 0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 |

| Group III | ||||||||

| WAL 17230 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.5 | 1 |

| WAL 13074 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | ≤1 |

| WAL 14467 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 2 | 0.25 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| WAL 16820 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.5 | 1 |

| WAL 17140 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.5 | 1 |

| WAL 16715 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 1 | ≤0.12 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | ≤1 |

Tested by CLSI agar dilution procedure.

Results for these two drugs are given as results for ampicillin.

Boldface values indicate results for strains that were resistant to the indicated drug.

Phylogenetic characterization.

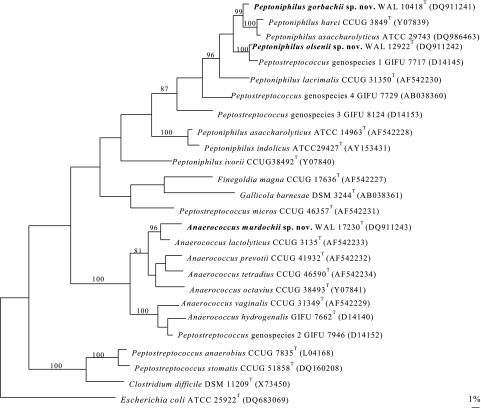

To assess the genealogical affinity between the unknown bacteria and their relationship with other taxa, their 16S rRNA gene sequences were determined. Pairwise analysis showed that all of the isolates of the same group were phylogenetically closely related to each other (>99.5% sequence similarity). Sequence searches of GenBank and Ribosomal Database Project libraries for validly described species revealed that the unknown organisms were members of the Firmicutes phylum, and each group represents a previously unknown subline within Clostridium cluster XIII; groups I and II are most closely related to Peptoniphilus harei, and group III is most closely related to Anaerococcus lactolyticus. Pairwise comparison revealed approximately 2.5%, 7.0%, and 3.5% sequence divergences between the unknown bacterial groups I, II, and III, respectively, and the type strains of their closest valid species based on almost the full length of 16S rRNA gene sequences (>1,400 nucleotides). Although there is no precise correlation between percent 16S rRNA sequence divergence values and species delineation, it is now generally accepted that organisms displaying divergence close to 3% or more do not belong to the same species (19). A tree, constructed by the maximum parsimony method, depicting the phylogenetic affinity of the three novel groups as exemplified by strains WAL 10418T, WAL 12922T, and WAL 17230T, respectively, is shown in Fig. 1 and confirmed the placement of the unknown bacteria in Clostridium cluster XIII. It is evident from the branching pattern in the tree that the strains of groups I and II possess a close relationship with the type strain of P. harei and that strains of group III possess a close relationship with the type strain of A. lactolyticus (90% bootstrap resampling value).

FIG. 1.

Unrooted tree showing the phylogenetic relationship of Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov., Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov., and Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov. with the other related taxa. The tree, constructed using the maximum parsimony method, was based on a comparison of approximately 1,400 nucleotides. Bootstrap values, expressed as a percentage of 1,000 replications, are given at branching points. Bar, 1% sequence divergence.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report on the characterization of three groups of unknown bacteria that were isolated from human clinical infections. The strains of groups I and II were isolated from relatively low-grade infections of lower extremities. Background factors were neuropathy and diabetes mellitus. These organisms appear to be of relatively low virulence since they were always found in mixed culture and were not recovered from blood culture or very serious infections. The unknown bacterial isolates in groups I and II were misidentified as P. asaccharolyticus by the Rapid ID 32A biochemical kit. However, 16S rRNA sequencing revealed approximately 10% sequence divergence between the novel species and the type strain of P. asaccharolyticus. Both of the novel species shared relatively high sequence similarity with the type strain of P. harei (97.5% between group I and P. harei and 93.0% between group II and P. harei). The unknown bacterium of group II shares a relatively high sequence similarity (approximately 97.5%) with P. asaccharolyticus strain GIFU 7717.

Our data (17) clearly indicated that the strains previously recognized on phenotypic grounds as P. asaccharolyticus are genetically diverse; this is in good agreement with data published previously (2, 3, 6, 12). The comment by Holdeman-Moore et al. that one should be cautious in reporting on isolation and incidence of P. asaccharolyticus still applies (6). It is known that the type strain of P. asaccharolyticus is highly atypical in its whole-cell composition and some biochemical properties (9, 11). Our data based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis indicated that except for the unknown bacteria of groups I and II that we described above, most of the strains that were identified as P. asaccharolyticus phenotypically shared a relatively high sequence similarity (98.6%) with the type strain of P. harei (17). Further study involving DNA-DNA hybridization is being carried out to determine whether this group of so-called P. asaccharolyticus bacterial strains merits a novel species or a subspecies of P. harei. In this paper, we regard this group of bacteria as P. harei (P. harei II in Table 1) due to the relatively high sequence similarity (98.6%) and high similarity of phenotypic characteristics between them.

The unknown bacteria of group III may correspond to the “β-GAL group” described by Murdoch and Mitchelmore (9). The strains of group III consistently produce several enzymes such as β-galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase and proteolytic enzymes such as arginine and leucine arylamidase, which match the characteristics of the “β-GAL group.” The most interesting feature of the “β-GAL group” is its association with significant infections. In the survey by Murdoch et al. (10), “β-GAL group” strains comprised 5% of all isolates and were cultured from patients with various infections. In this study, the strains of group III were isolated from infected foot ulcers, infected thumb, infected sternum, and infected soft tissue of the neck. Background factors were human immunodeficiency virus infection, trauma, neuropathy, and diabetes mellitus. The group III strains may be of relatively high virulence since they were recovered from serious infections. Therefore, it is important to systematically describe this bacterial species to allow further definition of its clinical significance.

Although the three unknown bacteria display a number of similarities to their close phylogenetic relatives, the 16S rRNA gene sequence divergence of approximately 3% or more between them demonstrates that these organisms are phylogenetically distinct. Support for the separation of the unknown bacteria from their related bacterial species also comes from the phenotypic characterization. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis showed that the closest phylogenetic relatives to the unknown bacteria of groups I and II are P. harei, and both bacteria were phenotypically similar to P. asaccharolyticus, but they can be distinguished easily from P. harei and P. asaccharolyticus by several biochemical characteristics. For example, organisms of group I produce glutamyl glutamic acid arylamidase and serine arylamidase but P. harei and P. asaccharolyticus do not. Organisms of group II produce phenylalanine arylamidase and serine arylamidase but P. harei and P. asaccharolyticus do not. The two groups of unknown organisms are like each other in terms of biochemical characteristics. However, they can be differentiated by several enzyme tests. By the Rapid ID 32A test, group I showed a strongly positive reaction for glutamyl glutamic acid arylamidase, whereas group II was negative. In contrast, alkaline phosphatase, alanine arylamidase, and leucyl glycine arylamidase (strong or weak) tests were positive for group II but were negative for group I. In addition, the groups can be differentiated from each other by their colony morphologies: colonies of strains of group I are flat, in contrast to those of group II strains, which are convex.

The strains of group III resemble A. lactolyticus, but they can be easily differentiated from A. lactolyticus by the urease test; the unknown bacteria of group III do not produce urease while A. lactolyticus does. The unknown bacteria also can be readily distinguished from other related gram-positive anaerobic cocci by various biochemical tests; Table 3 and a flow chart developed in another paper (18) summarize key characteristics for identification and differentiation of the unknown organisms from the other GPAC.

Based on both phenotypic and genotypic evidence, it is clear that the three groups of unknown isolates recovered from infections in humans represent three novel species. We propose that the unknown isolates of groups I, II, and III be classified as three novel species, Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov., Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov., and Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov., respectively.

Description of Peptoniphilus gorbachii sp. nov.

Peptoniphilus gorbachii (gorbachii, to honor Sherwood Gorbach, who has contributed so much to our knowledge of anaerobic bacteriology) cells are coccus shaped and gram positive. Typical cells are ≥0.7 μm. Colonies on brucella blood agar plates at 5 days are gray, flat or low convex, circular, entire, opaque colonies with a diameter of 1 to 2 mm. They are obligately anaerobic; spot indole variable; catalase, coagulase, urease, and nitrate negative; and asaccharolytic—acid is not produced from glucose. By the Rapid ID 32A test, all isolates produce similar profiles. Positive reactions are obtained for arginine arylamidase, phenylalanine arylamidase (strong or weak), leucine arylamidase, tyrosine arylamidase, glycine arylamidase, glutamyl glutamic acid arylamidase, histidine arylamidase, and serine arylamidase. The strains are indole variable. All the other tests are negative. In peptone-yeast extract broth and peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth, major amounts of acetic acid, moderate amounts of butyric acid, and trace amounts of propionic acid are produced by all isolates. The isolates are sensitive to kanamycin (1,000-μg) and vancomycin (5-μg) and resistant to colistin sulfate (10-μg) identification disks. Agar dilution tests show that all the strains are susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), cefazolin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC, ≤0.5 μg/ml), imipenem (MIC, ≤0.062 μg/ml), metronidazole (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml), penicillin G (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml), and vancomycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml). Four strains are susceptible to clindamycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml) while two strains show resistance to clindamycin (MIC, ≥64 μg/ml). Five strains are susceptible to penicillin G (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml) while one strain shows intermediate susceptibility to penicillin G (MIC, 1 μg/ml). The isolates are from human clinical specimens. The type strain is WAL 10418T = CCUG 53341T = ATCC BAA-1383T.

Description of Peptoniphilus olsenii sp. nov.

Peptoniphilus olsenii (olsenii, to honor Ingar Olsen, who has contributed much to our knowledge of anaerobic bacteriology) cells are coccus shaped and gram positive. Typical cells are ≥0.7 μm. Colonies on brucella blood agar plates at 5 days are gray, convex, circular, entire, opaque colonies, 2 to 3 mm in diameter with a whiter central peak. The strains are obligately anaerobic; spot indole variable; catalase, coagulase, urease, and nitrate negative; and asaccharolytic—acid is not produced from glucose. In peptone-yeast extract broth and peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth, major amounts of acetic acid, moderate amounts of butyric acid, and trace amounts of propionic acid are produced by all isolates. By the Rapid ID 32A test, all isolates produce similar profiles. Positive reactions are obtained for alkaline phosphatase, arginine arylamidase, leucyl glycine arylamidase (strong or weak), phenylalanine arylamidase, leucine arylamidase, tyrosine arylamidase, alanine arylamidase, glycine arylamidase, histidine arylamidase, and serine arylamidase. The strains are indole variable. All the other tests are negative. The isolates are sensitive to the kanamycin (1,000-μg), vancomycin (5-μg), and colistin sulfate (10-μg) identification disks. Agar dilution tests show that all strains are susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), cefazolin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC, ≤0.5 μg/ml), imipenem (MIC, ≤0.062 μg/ml), metronidazole (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml), and vancomycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml). The isolates are from human clinical specimens. The type strain is WAL 12922T = CCUG 53342T = ATCC BAA-1384T.

Description of Anaerococcus murdochii sp. nov.

Anaerococcus murdochii (murdochii, to honor D. A. Murdoch, who has contributed a great deal to our knowledge of anaerobic cocci) cells are coccus shaped and gram positive. Typical cells are ≥0.7 μm. Colonies on brucella blood agar plates at 5 days are gray, flat or low convex, entire, circular, often matt, 1 to 2 mm in diameter with whiter centers. They are obligately anaerobic; spot indole negative; and catalase, coagulase, urease, and nitrate negative. Acid is produced from glucose. In peptone-yeast extract broth and peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth, major amounts of butyric acid and acetic acid are produced by all isolates. By the Rapid ID 32A test, all isolates produce similar profiles. Positive reactions are obtained for arginine dihydrolase, β-galactosidase, alkaline phosphatase, arginine arylamidase, glycine arylamidase (strong or weak), histidine arylamidase (strong or weak), leucine arylamidase, and pyroglutamic acid arylamidase. β-Glucosidase, leucyl glycine arylamidase, alanine arylamidase, and serine arylamidase results are variable. Mannose is fermented, but not raffinose, when tested by the Rapid ID 32A system. All the other tests are negative. The strains are sensitive to vancomycin (5 μg) and resistant to colistin sulfate (10 μg); three strains are sensitive and two strains are resistant to kanamycin (1,000-μg) identification disks. Agar dilution tests show that one strain is resistant to clindamycin (MIC, ≥64 μg/ml), and three strains show intermediate susceptibility or resistance to penicillin (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml). All the others are susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml), cefazolin (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC, ≤0.5 μg/ml), clindamycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml), imipenem (MIC, ≤0.062 μg/ml), metronidazole (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml), and vancomycin (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml). The isolates are from human clinical specimens. The type strain is WAL 17230T = CCUG 53340T = ATCC BAA-1385T.

Acknowledgments

This work has been carried out, in part, with financial support from Veterans Administration Merit Review funds.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson, D. A., M. S. Boguski, D. J. Lipman, and J. Ostell. 1997. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezaki, T., N. Yamamoto, K. Ninomiya, S. Suzuki, and E. Yabuuchi. 1983. Transfer of Peptococcus indolicus, Peptococcus asaccharolyticus, Peptococcus prevotii, and Peptococcus magnus to the genus Peptostreptococccus and proposal of Peptostreptococcus tetradius sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 33:683-698. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezaki, T., H. Oyaizu, and E. Yabuuchi. 1992. The anaerobic gram-positive cocci, p. 1879-1892. In A. Balows, H. G. Truper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag KG, Berlin, Germany.

- 4.Ezaki, T., Y. Kawamura, N. Li, Z. Y. Li, L. Zhao, and S. Shu. 2001. Proposal of the genera Anaerococcus gen. nov., Peptoniphilus gen. nov. and Gallicola gen. nov. for members of the genus Peptostreptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1521-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finegold, S. M. 1977. Anaerobic bacteria in human disease. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 6.Holdeman-Moore, L. V., J. L. Johnson, and W. E. C. Moore. 1986. Genus Peptostreptococcus, p. 1083-1092. In P. H. A. Sneath, N. S. Mair, M. E. Sharp, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 2. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jousimies-Somer, H., P. Summanen, D. M. Citron, E. J. Baron, H. M. Wexler, and S. M. Finegold. 2002. Wadsworth-KTL anaerobic bacteriology manual, 6th ed. Star Publishing, Belmont, CA.

- 8.Li, N., Y. Hashimoto, and T. Ezaki. 1994. Determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences of all members of the genus Peptostreptococcus and their phylogenetic position. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murdoch, D. A., and I. J. Mitchelmore. 1991. The laboratory identification of gram-positive anaerobic cocci. J. Med. Microbiol. 34:295-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murdoch, D. A., I. J. Mitchelmore, and S. Tabaqchali. 1994. The clinical importance of gram-positive anaerobic cocci isolated at St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, in 1987. J. Med. Microbiol. 41:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murdoch, D. A., and J. T. Magee. 1995. A numerical taxonomic study of the Gram-positive anaerobic cocci. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:148-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murdoch, D. A., M. D. Collins, A. Willems, J. M. Hardie, K. A. Young, and J. T. Magee. 1997. Description of three new species of the genus Peptostreptococcus from human clinical specimens: Peptostreptococcus harei sp. nov., Peptostreptococcus ivorii sp. nov. and Peptostreptococcus octavius sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:781-787. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murdoch, D. A. 1998. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:81-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murdoch, D. A., and H. N. Shah. 1999. Reclassification of Peptostreptococcus magnus (Prevot 1933) Holdeman and Moore 1972 as Finegoldia magna comb. nov. and Peptostreptococcus micros (Prevot 1933) Smith 1957 as Micromonas micros comb. nov. Anaerobe 5:555-559. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murdoch, D. A., H. N. Shah, S. E. Gharbia, and D. Rajendram. 2002. Proposal to restrict the genus Peptostreptococcus (Kluyver & van Niel 1936) to Peptostreptococcus anaerobius. Anaerobe 6:257-260. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 5th ed. Approved standard M11-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 17.Song, Y., C. Liu, M. McTeague, and S. M. Finegold. 2003. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence-based analysis of clinically significant gram-positive anaerobic cocci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1363-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, Y., C. Liu, and S. M. Finegold. 2007. Development of a flow chart for identification of gram-positive anaerobic cocci in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:512-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stackebrandt, E., and B. M. Goebel. 1994. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:846-849. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tindall, B. J., and J. P. Euzeby. 2006. Proposal of Parvimonas gen. nov. and Quatrionicoccus gen. nov. as replacements for the illegitimate, prokaryotic, generic names Micromonas Murdoch and Shah 2000 and Quadricoccus Maszenan et al. 2002, respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:2711-2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]