Abstract

PCR-restriction fragment length poymorphism (PCR-RFLP) is a simple, robust technique for the rapid identification of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. One hundred consecutive isolates from a Vietnamese tuberculosis hospital were tested by MspA1I PCR-RFLP for the detection of isoniazid-resistant katG_315 mutants. The test had a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 100% against conventional phenotypic drug susceptibility testing. The positive and negative predictive values were 1 and 0.86, respectively. None of the discrepant isolates had mutant katG_315 codons by sequencing. The test is cheap (less than $1.50 per test), specific, and suitable for the rapid identification of isoniazid resistance in regions with a high prevalence of katG_315 mutants among isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates.

Tuberculosis (TB) control is threatened by increasing resistance to first-line antituberculous agents. The WHO estimates that in the year 2004, 4.3% of new TB cases globally were multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) (29), defined as resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampin. Treatment regimens for MDR-TB are more complex, less potent, more toxic, and more expensive than first-line regimens, resulting in poorer tolerability and adherence and higher morbidity and mortality rates. Early identification of drug-resistant and particularly MDR strains is routine in developed low-prevalence countries, but the methods are currently unavailable to and too costly for resource-poor nations, where the burden of disease is greatest. Early identification of MDR-TB is crucial in order to permit the timely administration of appropriate drug regimens and could potentially improve the efficacy of MDR treatment schemes, such as directly observed treatment, short course-plus.

Isoniazid is a prodrug that is activated through cleavage by catalase peroxidase, the product of the katG gene. The active drug has a complex mode of action, which remains to be fully elucidated but principally targets mycolic acid biosynthesis pathways. Upregulation of the inhA gene product, an enoyl-ACP reductase, can overwhelm the impact of isoniazid.

Resistance to isoniazid is achieved through mutations in the katG gene, predominantly at codon 315, and in the inhA promoter for the majority of isolates. Mutations in other genes, such as ahpC and ndh, have been implicated in isoniazid resistance, but their roles are not yet proven. A role for kasA gene mutation in isoniazid resistance has recently been discredited (7). Many isolates are isoniazid resistant without any mutations in known target genes, and the mechanism of resistance for these isolates remains obscure.

Phenotypic sensitivity testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is time-consuming, requiring 2 to 4 weeks from primary specimen in settings with rapid liquid culture systems, such as BACTEC MGIT 960, and 6 to 8 weeks in settings with solid-medium culture (14).

Several approaches to the rapid identification of isoniazid resistance have been reported in the literature, including real-time PCR (22), single-strand-conformation polymorphism analysis (20), dot blots (25), chips (1, 13), and multiplex-allele-specific PCR (MAS-PCR) (12).

The PCR-RFLP approach has several advantages; it is cheap, robust, and simple to both perform and interpret, requiring only basic PCR equipment.

MspA1I digestion for the identification of the katG_315 mutation, as discussed here, has been described previously (9, 24, 27). The MspA1I restriction enzyme step also allows the detection of mutations other than katG_S315T at the 315 codon site, increasing the sensitivity of the test over MAS-PCR and still giving a positive identification of both mutant and wild-type genes. It does not detect the very rare katG_S315R (AGC→CGC) mutation (6).

Commercial molecular hybridization tests, such as INNO-LiPA RIF TB (Innogenetics, Zwijnaarde, Belgium) and MDRTBI (Hain Lifesciences, Nehren, Germany), while sensitive and specific (10), are too costly for routine use where the burden of disease is greatest. Both of these tests are based on reverse hybridization of a PCR product to membrane-bound probes. The INNO-LiPA RIF TB test detects mutations in the rpoB gene and consequently detects only rifampin resistance. However, rifampin resistance can be used as a surrogate marker of MDR-TB in many settings (21, 26). The MDRTBI test has probes targeted to both rpoB and katG mutations for the positive identification of MDR strains.

The identification of isoniazid resistance in the absence of rifampin resistance is important in settings where primary resistance to both isoniazid and streptomycin is high. Dual resistance to isoniazid and streptomycin, without MDR, has been strongly associated with an increased risk of treatment failure (odds ratio [OR] = 4.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 26) or relapse (OR = 3.3; 95% CI, 1.2 to 8.5) and with acquired MDR (OR = 6.6; 95% CI, 1.4 to 32) on a standard WHO regimen (2 months of streptomycin, rifampin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide; 6 months of isoniazid and ethambutol [2SRHZ/6HE]) (17). Around 25% of primary isolates are isoniazid resistant in Ho Chi Minh City, and 15% are isoniazid and streptomycin dual resistant (15).

The aim of the current study was to develop a rapid, simple PCR-RFLP screening test for the identification of isoniazid resistance from positive M. tuberculosis cultures. Previous sequencing data on isoniazid-resistant isolates from Vietnam indicated that around 80% of isoniazid-resistant isolates could be detected through katG_315 analysis, with katG_S315T being by far the most prevalent mutation (71%) (3). A restriction enzyme test specific for digestion of the CMGCKG site, found at wild-type katG_315, was therefore developed. The test was expected to detect all the mutations at codon 315 previously identified in Ho Chi Minh City: G944C (S315T), G944A (S315N), G944T (S315I), A943G (S315G), and G944C/C945G (S315T) (3). Rare isolates (<1% of isoniazid-resistant isolates) that lack the katG gene would not produce an amplicon in the initial PCR (28).

To assess specificity, the PCR-RFLP was tested on 47 DNA extracts from M. tuberculosis isolates with previously determined katG sequences (3). The test was 100% specific and was therefore tested prospectively on 100 positive M. tuberculosis cultures collected from patients at the Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (PNT TB hospital), Ho Chi Minh City.

The costs of the test in routine use were also calculated, based on minimum equipment requirements, costs of reagents available locally, and a batch size of 10 isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Initial testing was done on 47 cultures with known katG gene sequences: 20 with S315T mutations, 20 isoniazid-sensitive isolates (wild-type katG), 2 S315N, 2 S315I, 1 S315G, 1 S315T/T308T double mutant, and 1 isolate with a katG whole-gene deletion.

The test was then prospectively evaluated on 100 M. tuberculosis cultures from pulmonary TB patients at the PNT TB Hospital during April 2006. An aliquot of the first 20 isolates processed for phenotypic drug susceptibility testing each Wednesday was also tested by PCR-RFLP. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) and the PCR-RFLP test were performed blind by two different operators. The sensitivity and specificity of the PCR-RFLP were determined at the end of the study. Any isolate that produced discrepant results with the two tests was sequenced in the katG gene to determine the katG_315 sequence.

DNA extraction.

A single colony from culture was dispersed in 50 μl distilled water, and an equal volume of chloroform was added. The tube was vortexed, heated at 80°C for 20 min, vortexed again, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min. Five microliters of the upper aqueous layer was taken for PCR. Three control isolates were included with each run: one wild-type positive control, one katG_S315T mutant positive control, and one negative control (water).

PCR.

PCR of a 519-bp region of the katG gene was carried out with the primers 5′-GGTCGACATTCGCGAGACGTT-3′ and 5′-CGGTGGATCAGCTTGTACCAG-3′ from Marttila et al. (11). The reaction mixture had a final concentration of 0.3 μM each primer, 0.15 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 3 mM MgCl2 with 0.75 U Taq per reaction (Bioline, United Kingdom) (1× Bioline buffer supplied with enzyme). Five microliters of DNA extract was added to 15 μl reaction mixture, and the PCR was carried out in a Tetrad PCR machine (Bio-Rad, United Kingdom) with the following program: 10 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 1 min at 68°C, and 15 s at 72°C, followed by a further 25 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 68°C, and 15 s at 72°C.

Restriction enzyme digest.

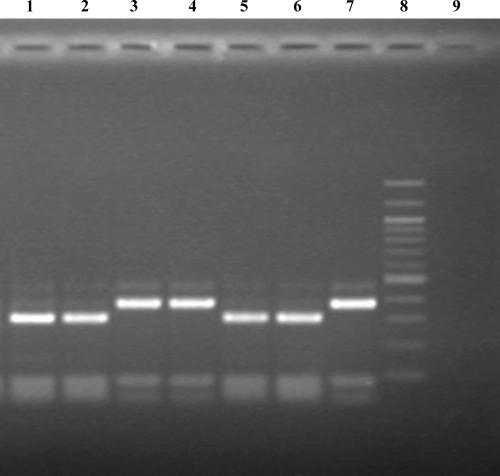

Ten microliters of restriction enzyme mixture was added to each PCR mixture to give a final volume of 30 μl containing a final 0.5 U of MspA1I (New England Biolabs), 0.7× New England Biolabs buffer 4 (supplied with enzyme), 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 h in the PCR machine. The products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel. A 309-bp band indicated a wild-type katG_315 codon. A 377-bp band indicated a mutant type katG_ 315 codon and therefore izoniazid resistance (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PCR-RFLP for the katG_315 mutation conferring isoniazid resistance in M. tuberculosis. Lanes 1, 2, and 5, sensitive clinical isolates; lanes 3 and 4, resistant clinical isolates; lane 6, sensitive control (309-bp band); lane 7, resistant control (377-bp band); lane 8, 100-bp ladder; lane 9, negative control.

Phenotypic sensitivity testing.

Phenotypic sensitivity testing for isoniazid resistance was carried out at 0.2 μg/ml by the 1% proportion method at the PNT TB hospital, according to WHO protocols.

Sequencing.

PCR products were amplified using primers as for the PCR-RFLP test with a program of 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 68°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s.

PCR products were purified with QIAgen PCR purification kits (QIAGEN, United Kingdom) and then served as templates for cycle-sequencing reactions. Both strands of each product were sequenced with CEQ Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Quick Start kits (Beckman Coulter, Singapore) in half-volume reactions using the same primers. The thermal-cycling program was 96°C for 20 s, appropriate annealing temperature for 20 s, and 60°C for 4 min for 30 cycles, followed by holding at 4°C. The cycle-sequencing products were subjected to ethanol precipitation steps according to the manufacturer's instructions and sequenced on the CEQ8000 system (Beckman Coulter, Singapore).

MAS-PCR.

MAS-PCR was used to screen for the inhA −15C→T mutation in discrepant isolates. The primers were TB92 (3′-CCTCGCTGCCCAGAAAGGGA-5′; 0.2 μm) and TB93 (3′-ATCCCCCGGTTTCCTCCGGT-5′; 0.05 μM) from Telenti et al. (19a), with the internal primer inhA Rmut (5′-AGTCACCCCGACAACCTATTA-5′; 0.25 μM). The PCR mixture used 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.75 U Bioline Taq (Bioline, United Kingdom), and 1× Taq buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Reaction mixtures were amplified in a Tetrad PCR machine (MJ Research, Hercules, Bio-Rad, United Kingdom), with an initial 2-min denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 15 s at 64°C, and 30 s at 72°C, with a final 2-min elongation at 72°C.

The presence of two bands at 174 bp and 248 bp indicated a mutant allele (inhA −15C→T). Wild-type isolates generated only a single band at 248 bp.

Costs.

Cost calculations were based on a batch size of 10 isolates, with all reagents purchased through local distributors and an exchange rate of 15,900 VND to the U.S. dollar. Equipment cost estimates were based upon locally available catalogue prices. The cheapest appropriate models were selected for calculations rather than the relatively expensive multiplate gradient models used in our laboratory, as only a basic thermocycler is required to perform the test. Costs were averaged and rounded up to the nearest $50. Final costs were estimated in U.S. dollars.

RESULTS

Retrospective culture analysis.

The test was 100% specific for the detection of the katG_315 mutant codon on 47 retrospective cultures with known katG_315 sequences. The 20 isoniazid-sensitive isolates produced a wild-type 310-bp band, and 27 resistant isolates with miscellaneous mutations at katG_315 generated a 378-bp band (Fig. 1). The isolate with katG deleted failed to generate an amplicon, as predicted, and the result was therefore “uninterpretable.” This DNA extract generated a product with other PCR-based tests, including spoligotyping and rpoB and inhA sequencing (data not shown).

Prospective culture analysis.

Of 100 M. tuberculosis cultures tested at the PNT TB Hospital by PCR-RFLP, 35 were resistant, 64 were wild type, and 1 isolate generated both wild-type and resistant bands and was therefore deemed to be a mixed culture.

By phenotypic DST, 43 isolates were resistant to isoniazid (one of which was identified as Mycobacterium fortuitum), 55 were sensitive, and 2 failed to return a result due to failed growth or contamination (both of which were sensitive by PCR-RFLP). Excluding the two isolates that failed to return a result by DST and the M. fortuitum isolate, the sensitivity of the PCR-RFLP test was 80% and the specificity was 100%. The positive predictive value and negative predictive value were 1 and 0.86, respectively.

Nine discrepant isolates were sequenced in the katG gene, including seven isolates that returned a sensitive PCR-RFLP/resistant DST result, one isolate (RE188) that returned a mixed resistant/sensitive PCR-RFLP result with a resistant DST result, and 1 isolate that returned a resistant PCR-RFLP result but was identified as M. fortuitum by DST (RE180). These isolates were also screened for the inhA −15C→T mutation by MAS PCR. A summary of the discrepant isolates is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

katG gene sequences of isolates showing nine discrepant results with PCR-RFLP and phenotypic DST

| Isolate no. | Result

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-RFLP | DST | katG sequencing | inhA −15C→T MAS PCR | |

| RE180 | Resistant | M. fortuitum | S315T | WT |

| RE188 | Sensitive/resitant | Resistant | S315T/WTa | WT |

| RE194 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | −15C→T |

| RE207 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | WT |

| RE220 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | WT |

| RE227 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | WT |

| RE239 | Sensitive | Resistant | L378M | −15C→T |

| RE250 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | −15C→T |

| RE259 | Sensitive | Resistant | WT | WT |

Isolate RE188 showed a heteropeak (G/C) at katG_315, nucleotide 944. WT, wild type.

The sequencing results confirmed that isolate RE180 contained M. tuberculosis DNA and carried a katG_S315T mutation. Isolate RE188 produced a heteropeak for the relevant mutation at codon 315 (G944C/wild type), confirming that it contained a mixed population of resistant and sensitive organisms. The six remaining isolates carried a wild-type katG_315 codon, with one isolate (RE239) carrying a novel mutation in katG, C1132A (L378M), confirming that in all these isolates resistance was attributable to mutations at sites other than katG_315.

The median time to positive culture was 32 days (range, 19 to 55 days; data were available for only 58 cultures). Phenotypic DST testing required a further 41 days to return a result, with PCR-RFLP returning a result within 1 day.

Costs.

The capital equipment required for the test consists of a basic PCR machine (approximately $3,000), a gel tank ($550), a power pack ($1,600), a transilluminator ($1,000), a camera ($400), and four pipettes ($1,000). The total capital costs are approximately $7,550. However, this equipment can also be used for other tests once it is purchased and is already available in many reference level laboratories.

If 10 isolates are processed per batch, with three controls (a positive mutant control, a positive wild-type control, and a negative control), the cost of each test is $1.50 per isolate. Labor costs were not included in this calculation.

DISCUSSION

The MspA1I PCR-RFLP rapid test described above showed 100% specificity and 80% sensitivity in the routine identification of isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis. It is affordable and simple to perform. It was also possible to obtain screening results by PCR-RFLP for three isolates that failed to return results by phenotypic DST due to failed regrowth or contamination. Isolate RE180 was originally identified as M. fortuitum at the PNT laboratory, and the presence of M. tuberculosis DNA, shown by katG sequencing, in the original culture extract of isolate RE180 suggests that a laboratory contamination event at the phenotypic DST subculture stage led to the growth of M. fortuitum. However, it is impossible to rule out contamination of an M. fortuitum sample with M. tuberculosis DNA during PCR-RFLP sample processing for DNA extraction. Unfortunately, clinical data were not available from the patient to determine if M. tuberculosis was isolated from later samples.

The early detection of isoniazid resistance is an important step in reducing the use of drug resistance-amplifying regimens, particularly with the increasing availability of second-line drugs through schemes such as DOTS-PLUS. Mutations in katG_315 are associated with higher MICs for isoniazid than mutations in the inhA promoter and therefore are probably of greater clinical significance (18, 23, 24). Variations in the outcomes of standard treatment regimens with a primary isoniazid-resistant organism are multifactorial, but the MIC for the isolate may be a contributing factor.

Vietnam has an estimated primary isoniazid resistance rate of 25% in Ho Chi Minh City (15). Despite having a well-functioning National Tuberculosis Program (NTP) administering DOTS according to WHO guidelines (8), drug resistance continues to rise. It has been speculated that this is due to high rates of primary isoniazid resistance in conjunction with the use of isonizid/ethambutol continuation phase regimens (16). Of greatest concern is the evidence that this may be fueling the development of MDR-TB, which has seen an increase from 2.3% in 1997 to an estimated 3.8% in 2005 (15). There is therefore an urgent need for a cheap, rapid, simple test to diagnose isoniazid resistance prior to the continuation phase, when currently around 25% of patients in Vietnam effectively receive monotherapy due to polyresistance. Primary isoniazid resistance has been associated with the development of MDR-TB after treatment (17). The katG_315 mutation is associated with the development and transmission of MDR-TB, whereas other isoniazid resistance-conferring mutations, such as inhA −15C→T, are not (7, 23, 24).

The test described here is economical ($1.50 per isolate) and simple to perform. In routine laboratories, the cost per isolate is likely to be lower, as we used a batch size of 10 isolates for calculations whereas larger batch sizes of 20 to 30 could easily be processed with careful precautions against contamination, including the use of “clean” and “dirty” containment areas and dUTPs with enzyme digestion and increasing the number of negative controls in larger batches.

Currently, in the Vietnamese NTP, TB patients are tested for drug resistance only after the microbiological failure of first-line therapy. This is primarily because of cost and workload considerations. Although the PCR-RFLP test is not 100% sensitive for the detection of isoniazid resistance, it is 100% specific and can therefore be used as a rapid screening test to identify the majority of patients with isoniazid-resistant organisms. At $1.50 per test, it is also affordable. The test can be completed in 1 day and requires around 2 to 3 h of hands-on time if already-prepared PCR master mixtures are used. We are currently evaluating the test for routine use directly with smear-positive sputum.

Strategies for the rapid identification of drug resistance should be region specific. A test screening for katG_315 mutations is likely to be of the most use in regions with a high prevalence of this mutation, such as China, Russia, the former Soviet states, Vietnam, and Peru (3, 5). In Europe, a higher prevalence of inhA gene mutations indicates that a multiplex PCR or hybridization approach is warranted (2, 4, 19). The reasons for variations in mutation prevalence are unclear and may be related to TB control program differences or to variations in the predominant M. tuberculosis strains within a region. Assessment of strategies for the rapid identification of drug resistance should be made in the context of knowledge of the predominant resistance-conferring mutations in a region.

In Vietnam, several factors should be considered: high underlying isoniazid resistance, the rarity of rifampin resistance without isoniazid resistance, and diverse rifampin resistance mutation patterns complicating the identification of rifampin resistance (3). These factors suggest an approach based upon rapid isoniazid resistance screening, with subsequent rifampin resistance testing in isoniazid-resistant isolates.

The implementation of rapid resistance-screening tests in high-incidence areas must be carefully considered. In Vietnam, as in many developing countries, patients whose primary therapy fails are treated with a standard first-line retreatment regimen. Even after identification of drug resistance by DST, TB therapy is rarely modified, even though treatment success rates with standard first-line drug retreatment regimens are known to be low. The advent of DOTS-PLUS schemes supported by the Green Light Committee for the economical procurement of drugs makes the implementation of rapid drug resistance screening and the use of second-line treatment regimes feasible within a well-established NTP such as is found in Vietnam. The use of the PCR-RFLP test to rapidly identify isoniazid resistance and to guide timely modification of therapy could potentially reduce both the generation and transmission of MDR-TB.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Wellcome Trust Grant 077078/Z/05/Z.

We thank the staff of Pham Ngoc Thach Microbiology laboratory for assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aragon, L. M., F. Navarro, V. Heiser, M. Garrigo, M. Espanol, and P. Coll. 2006. Rapid detection of specific gene mutations associated with isoniazid or rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates using non-fluorescent low-density DNA microarrays. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:825-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, L. V., T. J. Brown, O. Maxwell, A. L. Gibson, Z. Fang, M. D. Yates, and F. A. Drobniewski. 2005. Molecular analysis of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from England and Wales reveals the phylogenetic significance of the ahpC −46A polymorphism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1455-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caws, M., P. M. Duy, D. Q. Tho, N. T. Lan, D. V. Hoa, and J. Farrar. 2006. Mutations prevalent among rifampin- and isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a hospital in Vietnam. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2333-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coll, P., L. M. Aragon, F. Alcaide, M. Espasa, M. Garrigo, J. Gonzalez, J. M. Manterola, P. Orus, and M. Salvado. 2005. Molecular analysis of isoniazid and rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates recovered from Barcelona. Microb. Drug Resist. 11:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escalante, P., S. Ramaswamy, H. Sanabria, H. Soini, X. Pan, O. Valiente-Castillo, and J. M. Musser. 1998. Genotypic characterization of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Peru. Tuber Lung Dis. 79:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas, W. H., K. Schilke, J. Brand, B. Amthor, K. Weyer, P. B. Fourie, G. Bretzel, V. Sticht-Groh, and H. J. Bremer. 1997. Molecular analysis of katG gene mutations in strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1601-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazbon, M. H., M. Brimacombe, M. Bobadilla del Valle, M. Cavatore, M. I. Guerrero, M. Varma-Basil, H. Billman-Jacobe, C. Lavender, J. Fyfe, L. Garcia-Garcia, C. I. Leon, M. Bose, F. Chaves, M. Murray, K. D. Eisenach, J. Sifuentes-Osornio, M. D. Cave, A. Ponce de Leon, and D. Alland. 2006. Population genetics study of isoniazid resistance mutations and evolution of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2640-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huong, N. T., B. D. Duong, N. V. Co, H. T. Quy, L. B. Tung, M. Bosman, A. Gebhardt, J. P. Velema, J. F. Broekmans, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2005. Establishment and development of the National Tuberculosis Control Programme in Vietnam. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9:151-156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung, E. T., K. M. Kam, A. Chiu, P. L. Ho, W. H. Seto, K. Y. Yuen, and W. C. Yam. 2003. Detection of katG Ser315Thr substitution in respiratory specimens from patients with isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis using PCR-RFLP. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:999-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makinen, J., H. J. Marttila, M. Marjamaki, M. K. Viljanen, and H. Soini. 2006. Comparison of two commercially available DNA line probe assays for detection of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:350-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marttila, H. J., H. Soini, P. Huovinen, and M. K. Viljanen. 1996. katG mutations in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates recovered from Finnish patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2187-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokrousov, I., T. Otten, M. Filipenko, A. Vyazovaya, E. Chrapov, E. Limeschenko, L. Steklova, B. Vyshnevskiy, and O. Narvskaya. 2002. Detection of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains by a multiplex allele-specific PCR assay targeting katG codon 315 variation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2509-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, H., E. J. Song, E. S. Song, E. Y. Lee, C. M. Kim, S. H. Jeong, J. H. Shin, J. Jeong, S. Kim, Y. K. Park, G. H. Bai, and C. L. Chang. 2006. Comparison of a conventional antimicrobial susceptibility assay to an oligonucleotide chip system for detection of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1619-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piersimoni, C., A. Olivieri, L. Benacchio, and C. Scarparo. 2006. Current perspectives on drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: the automated nonradiometric systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:20-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quy, H. T., T. N. Buu, F. G. Cobelens, N. T. Lan, C. S. Lambregts, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2006. Drug resistance among smear-positive tuberculosis patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 10:160-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quy, H. T., F. G. Cobelens, N. T. Lan, T. N. Buu, C. S. Lambregts, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2006. Treatment outcomes by drug resistance and HIV status among tuberculosis patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 10:45-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quy, H. T., N. T. Lan, M. W. Borgdorff, J. Grosset, P. D. Linh, L. B. Tung, D. van Soolingen, M. Raviglione, N. V. Co, and J. Broekmans. 2003. Drug resistance among failure and relapse cases of tuberculosis: is the standard re-treatment regimen adequate? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 7:631-636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy, S. V., R. Reich, S. J. Dou, L. Jasperse, X. Pan, A. Wanger, T. Quitugua, and E. A. Graviss. 2003. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1241-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rindi, L., L. Bianchi, E. Tortoli, N. Lari, D. Bonanni, and C. Garzelli. 2005. Mutations responsible for Mycobacterium tuberculosis isoniazid resistance in Italy. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9:94-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Telenti, A., N. Honore, C. Bernasconi, J. March, A. Ortega, B. Heym, H. E. Takiff, and S. T. Cole. Genotypic assessment of isoniazid and rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a bind study at reference laboratory level. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:719-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Temesgen, Z., K. Satoh, J. R. Uhl, B. C. Kline, and F. R. Cockerill III. 1997. Use of polymerase chain reaction single-strand conformation polymorphism (PCR-SSCP) analysis to detect a point mutation in the catalase-peroxidase gene (katG) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Cell Probes 11:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traore, H., K. Fissette, I. Bastian, M. Devleeschouwer, and F. Portaels. 2000. Detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from diverse countries by a commercial line probe assay as an initial indicator of multidrug resistance. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 4:481-484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Doorn, H. R., E. C. Claas, K. E. Templeton, A. G. van der Zanden, A. te Koppele Vije, M. D. de Jong, J. Dankert, and E. J. Kuijper. 2003. Detection of a point mutation associated with high-level isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using real-time PCR technology with 3′-minor groove binder-DNA probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4630-4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Doorn, H. R., P. E. de Haas, K. Kremer, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, M. W. Borgdorff, and D. van Soolingen. 2006. Public health impact of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with a mutation at amino-acid position 315 of katG: a decade of experience in The Netherlands. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Soolingen, D., P. E. de Haas, H. R. van Doorn, E. Kuijper, H. Rinder, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2000. Mutations at amino acid position 315 of the katG gene are associated with high-level resistance to isoniazid, other drug resistance, and successful transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1788-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Victor, T. C., A. M. Jordaan, A. van Rie, G. D. van der Spuy, M. Richardson, P. D. van Helden, and R. Warren. 1999. Detection of mutations in drug resistance genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a dot-blot hybridization strategy. Tuber Lung Dis. 79:343-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watterson, S. A., S. M. Wilson, M. D. Yates, and F. A. Drobniewski. 1998. Comparison of three molecular assays for rapid detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1969-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wojtyczka, R. D., S. Dworniczak, J. Pacha, D. Idzik, M. Kepa, Z. Wydmuch, S. Glab, M. Bajorek, K. Oklek, and J. Kozielski. 2004. PCR-RFLP analysis of a point mutation in codons 315 and 463 of the katG gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from patients in Silesia, Poland. Pol. J. Microbiol. 53:89-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, Y., B. Heym, B. Allen, D. Young, and S. Cole. 1992. The catalase-peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature 358:591-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zignol, M., M. S. Hosseini, A. Wright, C. L. Weezenbeek, P. Nunn, C. J. Watt, B. G. Williams, and C. Dye. 2006. Global incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 194:479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]