Abstract

FLAN (short for FLu ANnotation), the NCBI web server for genome annotation of influenza virus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/Database/annotation.cgi) is a tool for user-provided influenza A virus or influenza B virus sequences. It can validate and predict protein sequences encoded by an input flu sequence. The input sequence is BLASTed against a database containing influenza sequences to determine the virus type (A or B), segment (1 through 8) and subtype for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of influenza A virus. For each segment/subtype of the viruses, a set of sample protein sequences is maintained. The input sequence is then aligned against the corresponding protein set with a ‘Protein to nucleotide alignment tool’ (ProSplign). The translated product from the best alignment to the sample protein sequence is used as the predicted protein encoded by the input sequence. The output can be a feature table that can be used for sequence submission to GenBank (by Sequin or tbl2asn), a GenBank flat file, or the predicted protein sequences in FASTA format. A message showing the length of the input sequence, the predicted virus type, segment and subtype for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of Influenza A virus will also be displayed.

INTRODUCTION

The Influenza Genome Sequencing Project (1), funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), has generated sequence data for nearly 2000 isolates of Influenza virus A and B. As a collaborator of this project, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) annotates the sequences and releases them in GenBank as soon as the data are received. Because of the large number of sequences received in a short period of time, an automatic annotation procedure is desired.

The genomes of influenza virus A and B consist of eight RNA segments which encode one to two proteins each. The expression of the MP segment of influenza virus A and the NS segment of influenza virus A and B involve splicing. The hemagglutinin protein of influenza virus A is further processed into mature peptides. The relatively complicated gene expression patterns in these segments mean that general viral genome prediction tools, such as GeneMark (2) which uses heuristic approaches in finding open reading frames, cannot be applied to annotate spliced gene products or mature peptides in influenza viruses.

The Genome Annotation Transfer Utility (3) annotates viral genomes using a closely related reference genome. Although it can handle splicing and mature peptides, users have to maintain a set of reference sequences for all segments and variations of influenza viruses, and select the corresponding one every time a sequence is uploaded for annotation. Since only one reference genome can be used at a time, it is hard for users to select the right reference genome before the annotation.

We developed a program FLAN (short for FLu ANnotation) to automatically annotate genomes of influenza virus A and B based on existing protein sequences in GenBank. For each segment/subtype of the viruses, a set of sample protein sequences is maintained on the server. The input influenza sequence is then aligned against corresponding protein set with a ‘Protein to nucleotide alignment tool’ (ProSplign). The translated product from the best alignment to the sample protein sequence is used as the predicted protein encoded by the input sequence. This program has been used for the annotation of more than 21 000 published GenBank records of influenza virus A and B sequences generated from the NIAID Influenza Genome Sequencing Project, the St Jude Influenza Genome Project (4) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Here, we describe the web version of the FLAN program as part of the NCBI Influenza Virus Resource (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/).

METHODS

Type/segment/subtype identification

An input sequence is searched by BLAST (5) against a specialized influenza sequences database to determine the virus type (A or B), segment (1 through 8) and subtype for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of Influenza A virus. The database contains one reference sequence for each virus segment and each subtype of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase (available at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/INFLUENZA/ANNOTATION/blastDB.fasta). The top hit in the BLAST result is used to determine the virus type/segment/subtype of the input sequence.

Sample protein sequences

Representatives of published protein and mature peptide sequences for each virus segment and different subtypes for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of Influenza A virus are maintained on the server side (available in the PROTEIN-A and PROTEIN-B directories at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/INFLUENZA/ANNOTATION/). For the segments that encode proteins with large variations in amino acid sequences and mature peptide cleavage sites, more than one protein could be chosen to be included. For example, this collection currently has 16 different protein samples for hemagglutinin of influenza A virus. Based on the segment and subtype determined by the BLAST result, a subset of sample protein sequences is selected and aligned against the input sequence.

Protein-to-nucleotide alignment

A special global protein-to-nucleotide alignment tool, ProSplign (manuscript in preparation, available at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/TOOLS/ProSplign), was designed to accurately annotate spliced genes and mature peptides of influenza viruses. ProSplign also handles input sequences with insertions and/or deletions which may cause a frame shift in the coding region.

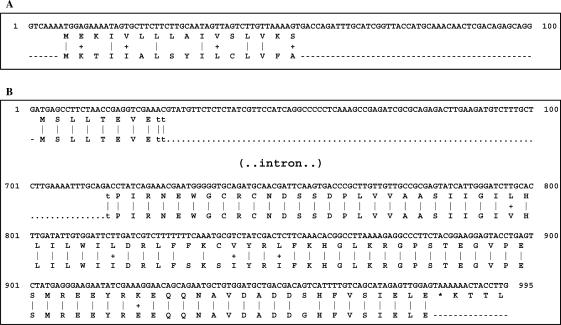

Annotation of mature peptides is a challenging task because their length could be very short. A fragment of influenza A virus hemagglutinin gene (GenBank accession number CY018949) query sequence is given in Figure 1A. The annotated mature peptide from the protein (GenBank accession number BAA21644) was used as a sample protein sequence. BLAST could not find any similarity between the two sequences because of the large sequence variation. Our solution is to use global alignment tool ProSplign. ProSplign alignment along with the peptide sequence is given in Figure 1A. The translation shown is used as the final annotation.

Figure 1.

(A) A fragment of ProSplign alignment of query influenza A virus segment 4 (at the top) against a signal peptide (first 16 amino acids of BAA21644, at the bottom). Similarity is too low for BLAST to find a significant hit. Translation in the middle becomes the annotation (see signal peptide on ABM22048). (B) The sample protein AAF99671 is aligned against the query sequence CY019262. ProSplign identified the GT/AG splicing junction. Amino acid threonine spans the splicing site. FLAN passes the coordinates of exons from the alignment to the final annotation.

Some segments of influenza viruses have a spliced gene. ProSplign was specially designed to handle alignments with introns. It automatically finds the exact splice site locations. An example of a spliced alignment is given in Figure 1B. The sample protein sequence global alignment includes start and stop codons as well as GT/AG splice sites. In that case translation is taken as the final annotation.

There are two types of gaps possible within the alignment of the input and sample sequences. A gap in the input sequence is considered a gap because it reflects the loss of sequence compared to a reference genome. A need to insert a gap in the aligned sample sequence is considered an insertion because it reflects additional sequence in the input sequence compared to the reference genomic sequence. If the length of the insertion/deletion is not a multiple of three, it is a frame shift, because the translation changes its frame over the gap. ProSplign gives a severe penalty for a frame shift indicating that there should be a serious reason for ProSplign to produce a frame shifted alignment. Such an alignment indicates a sequencing error or a critical mutation. ProSplign alignment shows the position of the frameshift and its exact length.

Interpreting alignment result and creating outputs

A successful protein-to-nucleotide alignment should pass the following criteria:

The input sequence should start with a correct start codon (or span the beginning of input sequence in case of partial 5′ end)

The input sequence should end with one of the stop codons (or span the end of input sequence in case of partial 3′ end)

The input sequence should have no frameshifts or internal stop codons

The number of exon(s) must be correct (two for the second protein of segments 7 and 8 of influenza A virus and segment 8 of Influenza B virus, one exon for all other segments/proteins)

If an alignment passes all four criteria shown, FLAN adopts the translated protein from the alignment as the protein prediction. Positions of the start, stop, splice sites (if present) and mature peptide are taken from the alignment. If an alignment does not pass any of the criteria, FLAN iterates further by aligning next sample protein from the reference subset. If none of the sample proteins can be used to produce a decent alignment, the best aligned sample protein (with the highest alignment score) will be used to generate an error report.

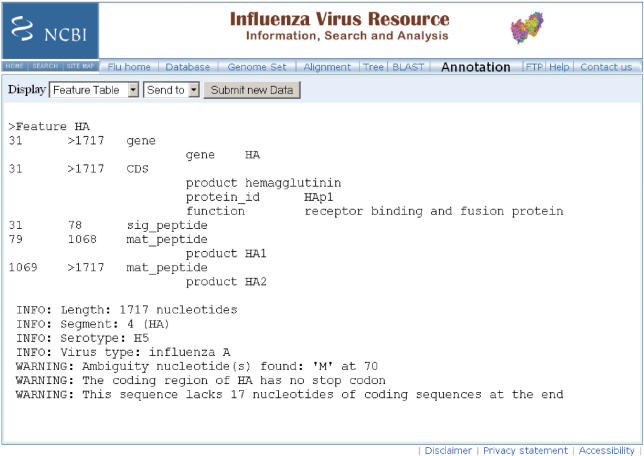

The first output of a successful annotation is a feature table (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Sequin/table.html), which is a five-column, tab-delimited table of feature locations and qualifiers (Figure 2). FLAN also creates the ASN.1, XML and GenBank formatted views of the same annotation, using the following NCBI developed utilities: tbl2asn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/tbl2asn2.html) and asn2xml (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Web/Newsltr/V14N1/toolkit).

Figure 2.

A sample output of the FLAN tool. The top part is a feature table showing feature locations (for gene and CDS) and qualifiers (gene and product). The lower part shows the diagnostic information about the sequence annotation.

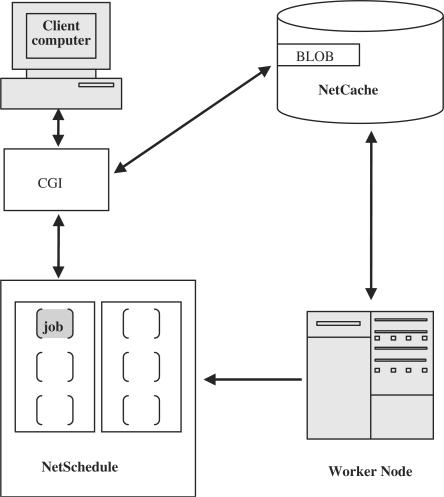

Netscheduling

The annotation of influenza sequences involves the resource-consuming alignment against a pre-selected protein set. Sometimes up to eight alignment attempts are performed before a good alignment is achieved. Moreover, a pre-selected set of sample proteins could be extended in the future which will further increase the calculation time.

Internally, FLAN is implemented as a NetSchedule service, an NCBI-developed framework which allows the execution of background CGI tasks for more than 30 s (default WEB front end timeout).

NetSchedule is designed to work as a queue manager with poll model of task distribution. Job submitter (in our case—annotate.cgi CGI) connects to a specific queue, submits a job to execution and receives a special string token (job key). After a while, a user can call the CGI and check the job status (‘Check status’ button). Jobs are executed by worker nodes that poll the queue, pick up jobs, compute and return the results (annotation and diagnostic messages, if any). A NetSchedule schema is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A NetSchedule (NS) schema. Client (end user) submits data to CGI at NCBI web server. CGI connects and sends data to the NetCache (NC) server. NC keeps data into blob and returns blob_id back to CGI. CGI connects to the NS server, submits request to execute the job with data from blob_id. NS puts this request in a queue and reports assigned job_id back to CGI. The job is waiting to be executed. WorkerNodes (WN) contacts NS constantly to check jobs in a queue. NS gives WN a job with blob_id of input data to execute. WN takes this blob_id, retrieves input data from NC, and executes the job. When execution is done, WN puts result in new blob2 in NC and gets blob2_id back from NC. WN connects to NS and reports job's execution status and blob2_id of result. NS answers to the status request from CGI with ready status and blob2_id. CGI gets blob2_id, connects to NC and retrieves blob2 with resulting data. Results data is presented to client.

THE WEB INTERFACE

FLAN is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/Database/annotation.cgi. The input data of FLAN is one or multiple sequences of influenza A virus or influenza B virus in FASTA format (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Sequin/sequin.hlp.html#FASTAFormatforNucleotideSequences), either pasted directly into a text box, or uploaded from a local file.

There are no parameters to select or enter to run this tool.

The output can be selected from a drop-down menu. The formats include a feature table, a GenBank flat file, the predicted protein sequences in FASTA format or XML. A message showing the predicted virus type, segment, and subtype for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of influenza A virus are displayed as well. Warning messages are shown along with the feature table, if the input sequence does not have a start/stop codon or contains ambiguities. In case the frameshifts are found, or a stop codon is introduced within the coding region, no feature table is produced and an error message is shown instead, indicating the nature (insertion, deletion or mutation), the length and the location of the error.

APPLICATIONS

There are three major applications for the FLAN web server.

FLAN can make the process easier to submit influenza virus sequences to GenBank, by eliminating the manual annotation step. The feature table generated by FLAN can be used directly by GenBank sequence submission tools such as Sequin (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Sequin/index.html) or tbl2asn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/tbl2asn2.html)

FLAN can be used to obtain protein sequences encoded by influenza viruses.

FLAN can be used as a validator for newly generated influenza sequences. The FLAN web server produces a complete list of diagnostic information for an input sequence, which includes predicted virus type, predicted virus segment, predicted virus subtype for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments of influenza A virus, missing start/stop codon, ambiguity sequences and frameshift. This information can help identify possible sequencing errors or human errors in segment/subtype assignment. Figure 2 shows a sample output of FLAN that contains such diagnostic information.

FLAN uses published influenza protein sequences as training sets. It will not annotate putative proteins reported in the literature (6,7) but not seen in sequence databases, nor will it predict putative novel proteins because of mutations. There are chances that it will not work as expected for some new sequence variations. Please report such cases to us so that we can improve this tool.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Anatoliy Kuznetsov for providing information for Figure 3 and Alexander Souvorov for helpful discussion. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Library of Medicine. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghedin E, Sengamalay NA, Shumway M, Zaborsky J, Feldblyum T, Subbu V, Spiro DJ, Sitz J, Koo H, et al. Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution. Nature. 2005;437:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besemer J, Borodovsky M. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3911–3920. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tcherepanov V, Ehlers A, Upton C. Genome Annotation Transfer Utility (GATU): rapid annotation of viral genomes using a closely related reference genome. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obenauer JC, Denson J, Mehta PK, Su X, Mukatira S, Finkelstein DB, Xu X, Wang J, Ma J, et al. Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates. Science. 2006;311:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1121586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb RA, Lai CJ, Choppin PW. Sequences of mRNAs derived from genome RNA segment 7 of influenza virus: colinear and interrupted mRNAs code for overlapping proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:4170–4174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih SR, Suen PC, Chen YS, Chang SC. A novel spliced transcript of influenza A/WSN/33 virus. Virus Genes. 1998;17:179–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1008024909222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]