Abstract

RNA pseudoknots are an important structural feature of RNAs, but often neglected in computer predictions for reasons of efficiency. Here, we present the pknotsRG Web Server for single sequence RNA secondary structure prediction including pseudoknots. pknotsRG employs the newest Turner energy rules for finding the structure of minimal free energy. The algorithm has been improved in several ways recently. First, it has been reimplemented in the C programming language, resulting in a 60-fold increase in speed. Second, all suboptimal foldings up to a user-defined threshold can be enumerated. For large scale analysis, a fast sliding window mode is available. Further improvements of the Web Server are a new output visualization using the PseudoViewer Web Service or RNAmovies for a movie like animation of several suboptimal foldings.

The tool is available as source code, binary executable, online tool or as Web Service. The latter alternative allows for an easy integration into bio-informatics pipelines. pknotsRG is available at the Bielefeld Bioinformatics Server (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/pknotsrg).

INTRODUCTION

RNA pseudoknots play an important role in many biological processes. They build the catalytic core of some ribozymes (1,2) and are an important building block of many structural RNAs. Pseudoknots are involved in telomerase activity (3) and they stimulate efficient programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting (-1 PRF), a mechanism used by a wide range of RNA viruses to encode two proteins within one genomic region. In a recent study (4) over a thousand of potential -1 PRF signals were detected in the yeast genome. The majority of signals however seem to direct the ribosome to premature termination codons. This suggests a mechanism of post-transcriptional gene regulation through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. Further genome wide studies have to elucidate this phenomenon. This and many more applications require fast RNA folding algorithms, that are also capable of folding pseudoknots.

Standard RNA folding programs (5,6) neglect pseudoknots for reasons of efficiency. While the standard methods need time proportional to the cube of the input sequence length, pseudoknot prediction is much more demanding. This issue has attracted a large body of bio-informatics work, where all approaches either abandon the model of free energy minimization, or make restrictions on the class of pseudoknots that can be recognized. The well-known algorithm by Rivas and Eddy (7), which is able to predict a restricted class of pseudoknots, needs O(n6) time and O(n4) memory space, where n is the sequence length. Even more restrictive, but more efficient by two orders of magnitude is the program pknotsRG by Reeder and Giegerich (8), requiring O(n4) time and O(n2) space. The new method presented here re-implements and extends this approach in several significant ways.

TOOL

The program pknotsRG enriches the usual RNA folding routines by the class of simple recursive pseudoknots. It uses the current thermodynamic energy model by the Turner group (5), extended by some pseudoknot specific values. pknotsRG offers three basic methods:

Standard MFE folding with pseudoknots: This method returns the structure of minimum free energy (MFE), containing a pseudoknot or not. In the latter case, this structure is identical to the MFE structure computed by RNAfold from the Vienna RNA package.

Enforced folding: The best structure in the folding space that contains at least one pseudoknot is reported. This is especially useful, when a pseudoknot is suspected, but not computed in the MFE folding.

Local folding: The pseudoknot with the best energy to length ratio is predicted. This mode helps to identify promising pseudoknot candidates in otherwise misfolded structures.

These methods were already available in the first version of pknotsRG. In this work we present an extension of this algorithm, including a complete re-implementation in the C programming language. This yields a drastically faster program and allows to accommodate the additional features with reasonable resource requirements.

The improved run time is best shown by an example: Folding a sequence of length 200 with the old version takes 80 s, whereas the new version finishes within 1 s. Due to lower memory consumption, we are now also able to fold very long sequences without being limited by the computer memory. The folding of 1000 nucleotides requires only 31 MB memory and 10 min.

Our first extension is the capability to compute near-optimal structures. Often the native structure of an RNA is not predicted as the MFE structure. This may stem from uncertainties in the energy parameters, or the molecule may not reach its MFE structure, either due to interactions with another molecule or by ending in a kinetic trap. In such a situation, alternative near-optimal structures may be better predictions. All methods of pknotsRG can now be run in a suboptimal mode, where all suboptimal solutions up to a user-defined threshold are computed. This is done in a way similar to RNAsubopt (9) from the Vienna RNA package for pseudoknot-free structures.

Another useful extension for large scale analysis, is a sliding window technique with adjustable window size and window position increment. For each position of the window the analysis is performed according to the user settings (e.g. enforced mode with 20% suboptimals). When the window is shifted, only the non-overlapping part of the new window has to be computed, the old part is be re-used. Depending on the window size and increment, this saves a considerable amount of time, much better than a wrapper program that folds each window independently.

Web server integration

The pknotsRG Web Server (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/pknotsrg) offers an easy and comfortable way to use the pknotsRG algorithm. Input has to be provided in a FASTA format containing one single RNA sequence. All non-nucleotide characters (i.e not A,C,G,T,U,N in upper or lower case) are removed from the sequence. The nucleotide ‘T’ is treated as ‘U’ during the folding routine, ‘N's are always unpaired. The user selects one of the three basic modes and optionally an energy threshold for suboptimal enumeration. If he wants to use the window mode, at least the window size has to be specified. The default window increment is set to one, unless otherwise specified. Depending on the user selection, there are three different ways how the result is displayed:

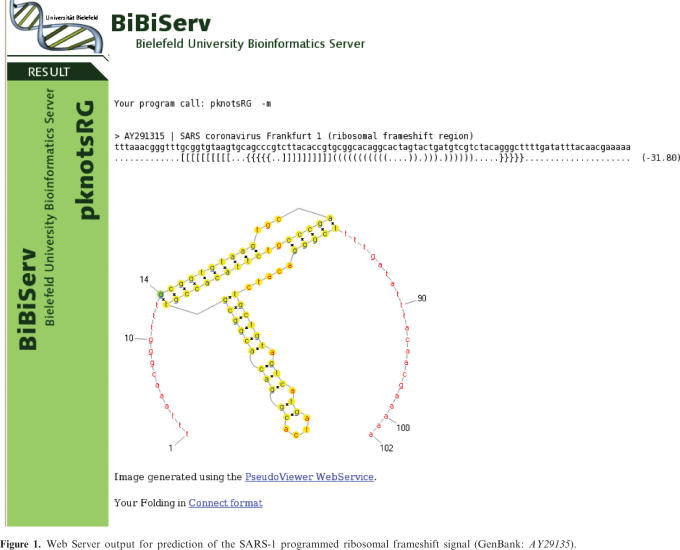

MFE structure only: The computed secondary structure and its energy are displayed in Vienna (Dot-Bracket) Notation. Here, a pair of opening and closing parenthesis denotes a base pair, a dot represents a single stranded nucleotide. A 2D visualization is generated using the PseudoViewer Web service (10). Also, a link to a Connect formatted file, originally used by Michael Zukers mfold (11), is provided. An example output is shown in Figure 1.

Suboptimal solutions: The list of suboptimal solutions is displayed as an RNAmovie (12). RNAmovies displays the individual suboptimal structures one after another with an adjustable number of intermediate transition steps. This allows for a smooth morphing from one structure to the next. Additionally, all suboptimal structures are displayed as Vienna strings along with their respective energy value at the bottom of the result page.

Window mode: For each window, the start and end position is displayed, followed by the result of the window folding. This may be one structure (as Vienna string), or many if the suboptimal mode is also selected. There is currently no vizualization provided, when using the window mode. However, the user can resubmit the sequence of an interesting window on its own. Then, the vizualizations explained in (i) and (ii) are automatically generated.

Figure 1.

Web Server output for prediction of the SARS-1 programmed ribosomal frameshift signal (GenBank: AY29135).

To ensure proper functionality two restrictions are imposed on the pknotsRG Web Server:

A maximum of 800 nucleotides is allowed for one submission. This guarantees the computation to finish within a few minutes. Note that smaller requests usually are answered instantly.

The suboptimal folding space of an RNA sequence grows exponentially with the energy threshold and sequence length. We prevent the Web service of returning too much data, by limiting the number of returned structures to the first 100, respectively, 1000 lines for the window mode.

The web interface is a convenient means for manual computation, but not designed for automated folding, i.e. integrated in an Internet-based bio-informatics pipeline. For this purpose, we provide a Web Service interface. This is particularly useful for researchers, who either cannot or do not want to install pknotsRG locally on their machines.

The interface is accessible from any computer in any programming language implementing the SOAP protocol. The Web Service Description Language (WSDL) file describes the functionality of the Web Service and can be found at (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/wsdl/pknotsRG.wsdl). Several software development environments can automatically generate program code from the WSDL file for the integration of a Web Service into a local application. We provide an example client written in Java on the project homepage.

The extensions presented here have been integrated into the original pknotsRG program in 2005 and 2006. Our server statistics indicate 1068 online uses and 773 downloads for local installation in 2006.

RESULTS FROM AN APPLICATION EXAMPLE

Recently, an unusual three-stemmed pseudoknot has been identified that promotes programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting in the SARS Coronavirus (13). The pseudoknot is thought to pause the ribosome during translation, which then shifts back by one nucleotide on the ‘slippery site’. This special pseudoknot seems to be conserved in all Coronaviruses, and thus could be a target for anti-viral therapeutics.

The 3-stem topology is predicted by pknotsRG as the optimal structure with an energy of -31.8 kcal/mol (Figure 1), using either the MFE or the enforced mode.

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE RECOGNIZED CLASS OF PSEUDOKNOTS

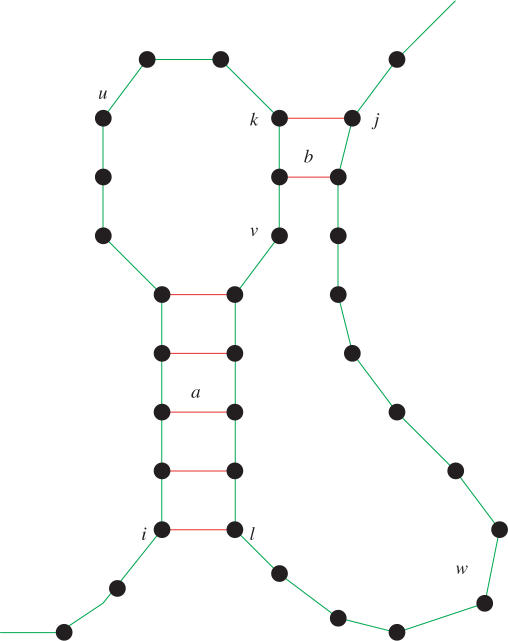

General pseudoknot prediction in energy-based models is a Non-deterministic Polynomial time NP-complete problem (14), and thus requires exponential run time. However, if we impose some restrictions on the helices forming the pseudoknots, we can achieve faster algorithms. The restrictions in pknotsRG are motivated by the observation, that most of the currently known pseudoknots are rather simple ones. They consist of only two helices, interacting in a crosswise fashion, as shown in Figure 2. If we allow the unpaired strands (u,v,w in Figure 2) to build secondary structures internally in an arbitrary way, including multiloops and pseudoknots, we call this class simple recursive pseudoknots.

Figure 2.

A simple pseudoknot formed by helices a and b. If the loop regions u, v, w fold further internal structures, including pseudoknots of this type, we have a simple recursive pseudoknot.

Our model further restricts this class by three canonization rules.

Rule 1: The 5′ and 3′ part of each pseudoknot helix must have the same length and must not have an interruption. This disallows bulges and internal loops inside pseudoknot stems.

Rule 2: The pseudoknot helices must have maximal length, i.e. if there is a possible base pair at either end, it must be closed.

Rule 3: If due to Rule 2 the helices would overlap, the first helix (a) is prioritized and the second one is shortened.

We call the resulting class canonical simple recursive pseudoknots (csr-pk). Note that all helices not participating in a pseudoknot are not affected by this canonization. A detailed discussion about the effects of canonization can be found in (8).

In an exhaustive analysis of the pseudoknot database PseudoBase (http://biology.leidenuniv.nl/~Batenburg/PKB.html), it was shown, that out of 212 known pseudoknots, 172 are simple recursive (8). Almost 80% of these are even canonical simple recursive pseudoknots. This shows the abundance of the class csr-pk within all validated structures.

IMPLEMENTATION

We will briefly sketch the way we implemented these ideas as an extension of the usual dynamic programming (DP) scheme for RNA folding [5,6]. Since only two helices participate in one pseudoknot, we loop over all possible knots in one O(n4) loop and store the result in a two-dimensional matrix. More detailed, for a pseudoknot between bases i and j, the algorithm enumerates all k and l, such that i < k < l < j. The first pseudoknot helix (a in Figure 2) starts at base pair i and l, the second (b) at position k and j. Now, we make use of our canonization: The maximal length of a helix can be pre-computed and stored in a two-dimensional array. Therefore, after choosing position k and l, the algorithm looks up the maximal helix lengths, h for (i, l) and h′ for (k, j) and checks the applicability of Rule 3. Having the stems fixed, the location of the three enclosed pseudoknot loops (u,v,w in Figure 2) follows directly: loop u ranges from position i + h + 1 to k−1, loop v from k + h′+1 to l−h−1, and loop w from l + 1 to j−h′−1. The best folding for these smaller subsequences has already been computed earlier in the DP scheme. The energy sum of the two pseudoknot helices and the loop folding energies gives us the total pseudoknot energy. The minimal one over all k and l, is stored is the two-dimensional pseudoknot matrix. This value competes with values of unknotted foldings for the interval (i, j).

During the (suboptimal) backtrace procedure the pseudoknot matrix is handled in the same way as the other matrices. Starting with a user-defined energy threshold thr, all suboptimal structures having an energy not more than thr larger than the optimal structure are backtraced. For each suboptimal structure s, the threshold is reduced by the energy difference to the optimal structure and the backtrace procedure is called recursively on the substructures of s, yet with a smaller threshold. At some point the threshold falls below 0, which means no further suboptimal structure within the user-defined energy band can arise from this backtrace.

AVAILABILITY

The program is available for download, both as C source code and precompiled binary executable for most common platforms (Solaris, Linux, Windows and Mac OS X). This version has none of the Web Server restrictions. It folds arbitrary long sequences and reports as many suboptimal solutions as the user requests.

The Windows version contains a basic graphical user interface, the other versions provide a powerful interactive command line tool. All versions are available in the download section of the project home page at http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/pknotsrg/.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jan Krüger for the Web Service implementation of pknotsRG and for the initial connection to the PseudoViewer Web Service. Funding to pay the open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Bielefeld University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Zhou K, Doudna JA. Crystal structure of a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. Nature. 1998;395:567–674. doi: 10.1038/26912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doudna JA, Cech TR. The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature. 2002;418:222–228. doi: 10.1038/418222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theimer CA, Blois CA, Feigon J. Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs JL, Belew AT, Rakauskaite R, Dinman JD. Identification of functional, endogenous programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift signals in the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(1):165–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofacker IL, Fontana W, Stadler PF, Bonhoeffer S, Tacker M, Schuster P. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatshefte f. Chemie. 1994;125:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivas E, Eddy SR. A dynamic programming algorithm for RNA structure prediction including pseudoknots. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:2053–2068. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeder J, Giegerich R. Design, implementation and evaluation of a practical pseudoknot folding algorithm based on thermodynamics. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wuchty S, Fontana W, Hofacker IL, Schuster P. Complete suboptimal folding of RNA and the stability of secondary structures. Biopolymers. 1999;49:145–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199902)49:2<145::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun Y, Han K. PseudoViewer: web application and web service for visualizing RNA pseudoknots and secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(suppl. 2):W416–422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuker M, Stiegler P. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary informations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9(1):133–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evers D, Giegerich R. RNA movies: Visualizing RNA secondary structure spaces. Bioinformatics. 1999;15(1):32–37. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plant EP, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Jacobs JL, Mukhopadhyay B, Hennig M, Dinman JD. a three-stemmed mRNA pseudoknot in the SARS coronavirus frameshift signal. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(6):e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyngsø RB, Pedersen CNS. RNA pseudoknot prediction in energy based models. J. Comp. Biol. 2001;7:409–428. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]