Abstract

Mother-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) accounts for up to 30% of worldwide chronic infections. The mechanism and high-risk period of HBV transmission from mother to infant are unknown. Although largely prevented by neonatal vaccination, significant transmission continues to occur in high-risk populations. It is unclear whether HBV can traverse an intact epithelial barrier to infect a new host. Transplacental transmission of a number of viruses relies on transcytotic pathways across placental cells. We wished to determine whether infectious HBV can traverse a polarized trophoblast monolayer. We used a human placenta-derived cell line, BeWo, cultured on membranes as polarized monolayers, to model the maternal-fetal barrier. We assessed the effects of placental maturity and maternal immunoglobulin on viral transport. Intracellular viral trafficking pathways were investigated by confocal microscopy. Free HBV (and infectious duck hepatitis B virus) transcytosed across trophoblastic cells at a rate of 5% in 30 min. Viral transport occurred in microtubule-dependent endosomal vesicles. Additionally, confocal microscopy showed that the internalized virus traverses a monensin-sensitive endosomal compartment. Differentiation of the cytotrophoblasts to syncytiotrophoblasts resulted in a 25% reduction in viral transcytosis, suggesting that placental maturity may protect the fetus. Virus translocation was also reduced in the presence of HBV immunoglobulin. We show for the first time that transcytosis of infectious hepadnavirus can occur across a trophoblastic barrier early in gestation, with the risk of transmission being reduced by placental maturity and specific maternal antibody. This study suggests a mechanism by which mother-infant transmission may occur.

Over 350 million people worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), with mother-infant transmission accounting for up to 30% of cases (19). Congenital infection results in chronic hepatitis in 90% of children and the risk of liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma and death in early adult life. The incidence of in utero transmission of HBV is unknown, as mother-to-infant transmission may occur prenatally, during delivery, or early postpartum. HBV has been found in amniotic fluid, breast milk, and vaginal fluids, as well as cord blood and infant gastric contents (7, 24). Maternal HBeAg status is the most significant factor determining risk of perinatal transmission, although maternal HBcAb-negative status and high HBsAg titer have also been reported to increase the risk of transmission (6, 61).

Vaccination of newborn infants reduces the likelihood of perinatal transmission from HBeAg-positive mothers by 79 to 90% (2), and the likelihood is further reduced by concurrent administration of HBV immunoglobulin (HBIG). While this implies that most transmission probably occurs perinatally, a clinically significant proportion of neonatal viral infection occurs despite vaccination. Among children vaccinated at birth, a 1 to 5% viral transmission rate is reported (8, 9, 26, 45, 64). Figures of vaccination failure rates from China are even higher (51, 62), suggesting that in utero HBV transmission may be more significant among high-risk groups. Additionally, infection risk has been related to the presence of DNA in the placenta (61) and to maternal viremia (4, 38), supporting an association between the state of maternal HBV during pregnancy and the risk of transmission to the baby. It is unclear whether HBV can traverse intact epithelial barriers to infect the fetus during gestation. HBV DNA has been found in reducing of the concentrations from the maternal to the fetal side of the placenta, suggesting cell-to-cell transfer of virus in the placenta and a possible mechanism for in utero transmission (61, 63).

The placenta is made up of chorionic villi consisting of a fetal capillary, villous stroma, and a layer of trophoblast cells consisting of syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts. These cells constitute a tight polarized epithelial monolayer comprising tight junctions preventing lateral and paracellular diffusion of substrates. Their apical surfaces are in contact with maternal blood, while their basolateral surfaces are contiguous with the fetal circulation. By 20 weeks, these cells terminally differentiate and fuse to form multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts (44). The syncytiotrophoblast constitutes the maternal-fetal barrier through which exchanges of substrates occur by transcytosis (15). Infection of the placenta and of the fetus depends on the permissiveness of these cells to the passage of pathogens. Maternal-fetal transmission of a number of viruses has been shown, with various consequences for the baby (17, 22, 23, 31).

We examined the ability of infectious HBV to cross the placenta in an in vitro system. Trophoblast-derived BeWo cells grown on semipermeable inserts form a polarized monolayer with tight junctions between cells as a model of the maternal-fetal barrier (5). We show that these cells transcytose cell-free HBV to a high degree in endosomes dependent on an intact cellular cytoskeleton. Utilizing duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) as an infectious model, we confirmed that the transcytosed virus remains infectious. HBV transcytosis was reduced with syncytiotrophoblast formation, as well as by specific antibody. The findings of this study suggest that infectious HBV may be able to transcytose across the maternal-fetal barrier in the first trimester.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

HBV was obtained from the supernatant of HepG2 cells transduced with Adeno-HBV (kind gift from J. Torresi, Melbourne, Australia). DHBV (strain D16) was obtained by sucrose-cushion purification of serum from infected ducklings. Brefeldin A, monensin, colchicine, and forskolin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. HBIG was a kind gift from P. Angus, Melbourne, Australia. Rabbit anti-ZO-1 antibody was purchased from Zymed. We purchased Alexa 488, Alexa 568 secondary antibodies, and TOTO-3 from Molecular Probes. [3H]inulin (1 mCi) was purchased from Amersham. HBV and DHBV PCRs were performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and primers supplied by Geneworks, Australia.

Cell lines.

BeWo cells were kindly provided by S. N. Breit, Sydney, Australia. These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Gibco) with glutamine, high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were used between passages 5 and 15 and seeded onto membranes at 1 × 105 cells·cm−2. HepG2 cells were maintained in minimal essential medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 1% glutamine. HepG2 cells grown on 75-mm cell culture flasks (BD Falcon) were transduced with Adeno-HBV and cultured for 14 days before cell supernatants were collected, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and quantified for HBV by PCR. Adeno-HBV-transduced HepG2 cells produce infectious HBV virions via all viral replicative intermediates (50).

Transcytosis studies.

BeWo cells were seeded to 70% confluence on six-well PET cell culture inserts, 1-μm pore size (BD Falcon), in a two-chambered system. In this system, BeWo cells form a polarized monolayer with tight junctions between cells, allowing access to both the apical and basolateral domains. Transepithelial resistance was measured daily at 37°C with a voltohmmeter (Millipore, Australia), and the monolayer was determined to be polarized and contiguous if corrected transepithelial resistance measurements exceeded 100 Ω·cm2. Blank inserts with media were used to zero between measurements. Cultures were not permitted to proceed for more than 5 days, to avoid overgrowth and cell layering. In addition, each transcytosis experiment included [3H]inulin in the apical supernatant to calculate passive diffusion. Briefly, we added 3.5 μCi/ml [3H]inulin apically, and 100-μl aliquots of the collected samples were mixed with scintillation liquid and counted. Percent [3H]inulin diffusion was calculated by comparing apical and basolateral levels, and we noted that diffusion remained constant between culture plates. Virus (107 copies·ml−1 of HBV or 108 copies·ml−1 of DHBV) was added to the apical domain of the polarized monolayers, and all of the basolateral supernatant was collected at (30-min) intervals and replaced with fresh warm medium. After three basolateral collections in the absence of drug, transcytosis was inhibited by brefeldin A (1 μg/ml), monensin (2 μM), colchicine (5 μM), or no drug. Drugs were administered to the cells in both the apical and basolateral chambers at identical concentrations. During sample collection, supernatant was replaced with fresh medium containing drugs. Apical supernatants were collected at the conclusion. Percent transcytosis was determined by calculation of the progressive virus titer.

DHBV titration.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the AMREP Animal Ethics Committee. Primary duck hepatocytes (PDH) were used to quantify the infectious virus titer according to a modification of a previously described method (1). PDH were prepared by collagenase perfusion of 7-day-old Pekin-Aylesbury ducklings, as described previously (52). DHBV-negative PDH were grown on glass coverslips for 48 h. Apical and basolateral supernatants from BeWo transcytosis experiments were clarified by centrifugation. These were serially diluted 10-fold in media and used to infect the hepatocytes in duplicate wells. The inoculum was left on the cells for 24 h and then removed and replaced with fresh medium. PDH were incubated for 7 days to allow infected foci to form. Coverslips were then fixed and stained with 1H1 DHBV pre-S antibody and visualized with Alexa 488 goat anti-mouse antibody. Foci were counted by fluorescence microscopy. An estimate of the infectious virus titer was determined by the average of duplicate well counts, with correction for the dilution factor.

Quantitative PCR.

Clarified apical and basolateral supernatants were treated with proteinase K (Promega) for 30 min. PCR was then performed in 25-μl reactions in a thermal cycler (LightCycler; Bio-Rad) according to the SYBR green protocol (Bio-Rad) using primers in the precore region of HBV, PC1 (GGGAGGAGATTAGGTTAA) and PC2 (GGCAAAAACGAGAGTAACTC) (25), or DHBV, DHBV03 (ACTAGAAAACCTCGTGGACT) and DHBV04 (GGGAGAGG-GGAGCCCGCACG) (56). Standards of a known quantity of plasmid HBV DNA were serially diluted in negative supernatant. Standards were processed in parallel with samples and tested in duplicate with each run to provide a standard curve for quantification.

Forskolin treatment.

BeWo cells were seeded to 70% confluence onto cell culture inserts and treated 24 h later with 80 μM forskolin in the apical and basolateral chambers. The cells were treated for 48 h before being thoroughly washed and fresh medium applied. Forskolin-induced cAMP production leads to terminal differentiation and fusion of BeWo cells to form syncytiotrophoblasts (58) but will also inhibit cell division, as differentiated syncytiotrophoblast cells do not divide. We had determined previously the ideal seeding density and treatment durations to maximize cell fusion without compromise of monolayer integrity from inhibition of cell division. Thus, we achieved BeWo monolayers that were contiguous and comprised both fused and solitary cells. [3H]inulin diffusion studies and transepithelial resistance measurements confirmed that the monolayers were intact. Cells were then fixed and stained for ZO-1 antibody and visualized with Alexa 488 and propidium iodide before examination by confocal microscopy. The numbers of nuclei and cell boundaries were counted in multiple fields, and their ratios were used to determine the percentage of cell fusion.

HBIG treatment.

BeWo monolayers were treated with purified HBIG for 72 h at 0, 100, or 1,000 mg/liter in both apical and basolateral supernatants. HBV was added to the apical domain, and basolateral supernatant was collected every 30 min and replaced with medium containing HBIG to maintain the concentration of HBIG throughout the experiment.

IgG ELISA.

As most HBV hyperimmune globulin comprises immunoglobulin G (IgG), the rate of transcytosis of HBIG across BeWo monolayers was determined by total IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A standard curve was obtained by serial dilution of HBIG of known concentration. Immunosorbent plates (Nunc) were coated with 100 μl of 0.01% monoclonal anti-human IgG Fc (Chemicon, Australia) in bicarbonate buffer. Plates were blocked in 3% skim milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline. Next, 100-μl samples were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Plates were then washed and conjugated with 100 μl of 0.02% sheep anti-human IgG horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) for 45 min at room temperature and detected with 100 μl of 1% 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine buffer (Chemicon), with the reaction being terminated with 2.5 M H2SO4 when color was visible. Absorbance was read at 450-nm and 620-nm wavelengths.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

BeWo cell monolayers used in the transcytosis studies described above were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.01% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline after the final collection. Semipermeable membranes on which the cells were growing for transcytosis experiments were then excised from the inserts and adhered to glass slides to allow for immunodetection and microscopic visualization. Cells were stained with 1H1 (monoclonal anti-pre-S DHBV antibody) (42) and rabbit anti-ZO-1 antibody (against the tight junction protein, zonula occludens-1). Alexa 568 goat anti-mouse and 488 goat anti-rabbit antibodies were used for visualization, and nuclei were stained with TOTO-3. Forskolin-treated BeWo cells were treated with anti-ZO-1 antibody as described above and visualized with Alexa 488 secondary antibody and propidium iodide.

Microscopy.

Immunofluorescence examination of PDH was performed with an Olympus IX70 microscope. Images of BeWo monolayers were acquired with a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 Nikon scanning confocal microscope with Lasersharp software. An optimal z plane through the monolayer was selected for each field to maximize visualization of the (apical) ZO-1 distribution while still detecting some signal from the (basolateral) very bright nuclear staining. Single xy images in this confocal plane were used. Raw TIFF images were processed with Adobe Photoshop.

Data analysis.

Data were imported from the primary sources into Microsoft Excel for analysis. Duplicates samples were always used. The error values shown in the results represent the standard error of the mean for each experiment. The two-tailed Student t test was used to determine the significance of differences between values. We accepted P values of <0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

HBV transcytoses across BeWo monolayers.

Confluent monolayers of BeWo cells were grown on semipermeable membranes, and medium containing cell-free HBV was added to the apical domains. Three 30-min basolateral medium collections were taken before and after the addition of drugs that inhibit specific transcytotic pathways (see “Transcytosis studies,” above). To each culture, brefeldin A, monensin, colchicine, or no drug was added. Transepithelial resistance of the BeWo monolayers did not vary with the addition of virus or drug (data not shown). Virus titer in the supernatants was determined by quantitative PCR. Results are given as means of pre- and posttreatment collections from duplicate wells. Percent transcytosis was calculated for each time point, allowing for progressive loss of virus from the apical to the basolateral domain.

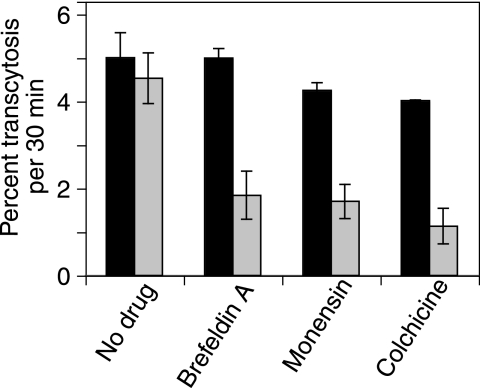

Five percent of apical HBV was efficiently transcytosed by polarized trophoblasts in 30 min (Fig. 1). Transcytosis of cell-free virus varied little in the no-treatment groups. The addition of brefeldin A, an agent that disrupts both the Golgi and endosomes (20, 30), markedly inhibited HBV transcytosis. Likewise, monensin, a Na+ ionophore that inhibits endosomal acidification (36), inhibited viral transcytosis from pretreatment levels of over 4% transcytosis to 1.7% in 30 min. Disruption of the cellular cytoskeleton with colchicine (32) resulted in a similar degree of marked inhibition of transcytosis. The degrees of inhibition from all of these agents were very similar, suggesting that they all inhibit different aspects of a single pathway. It appears from these data that cell-free HBV is transported from the apical to the basolateral surface of BeWo cells by transcytosis in endosomes and that these are reliant upon cytoskeletal elements for traffic.

FIG. 1.

Transcytosis of HBV across BeWo monolayers. BeWo cells were grown on semipermeable membranes, and HBV was added to the apical domain. Percent viral transcytosis before (black bars) and after (gray bars) administration of trafficking inhibitors was analyzed by PCR. Free HBV transcytosed at a rate of around 5% per 30 min. Brefeldin A and monensin markedly reduced transcytosis by endosomal inhibition. Transcytosis was also reduced by colchicine-induced disruption of the cellular cytoskeleton.

Viral transcytosis is inhibited at 4°C.

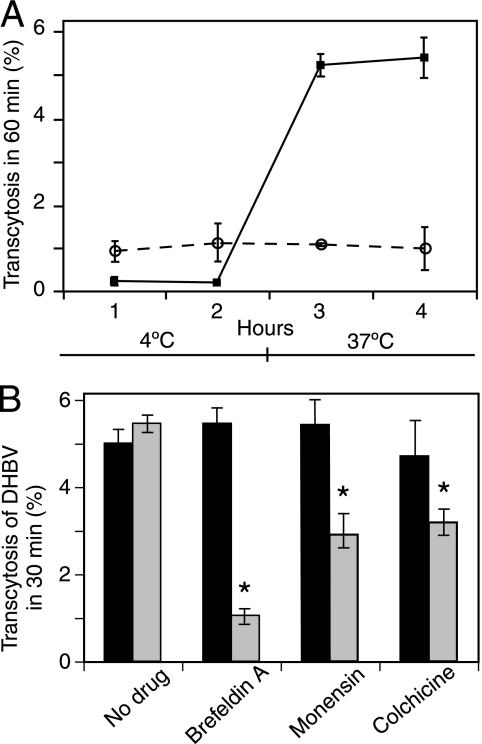

To determine whether virus was being transported by an active cellular process, the temperature dependence of viral translocation was examined. Monolayers of BeWo cells on membranes were incubated at 4°C for 1 h. At this temperature, energy-dependent cellular functions are largely inhibited, but passive diffusion of molecules should remain unaffected. DHBV and [3H]inulin were added to the apical supernatant of the BeWo monolayers. Basolateral collections of media were taken every 2 h, and cells were then rapidly warmed to 37°C and further collections were taken.

Figure 2A shows that at 4°C, with all cellular activity halted but diffusion minimally affected, there was very little virus detected in the basolateral supernatant. These cells, when warmed to 37°C, transcytosed virus effectively, indicating the energy dependence of viral transport. In addition, the rapid rate of transcytosis upon warming suggests that the virus had bound to cell surface molecules at 4°C, which are then internalized almost immediately upon cell warming. By contrast, [3H]inulin diffusion was not temperature dependent and remained at about 0.9% throughout the 4 h. In addition, the markedly higher rate of transport of the much larger DHBV virion than of the small, 5-kDa [3H]inulin molecule is indicative of active transport of virus rather than diffusion. Transcytosis of hepadnavirus in BeWo cells appears to occur through a process that requires cellular metabolism and perhaps through a receptor-mediated mechanism.

FIG. 2.

Transcytosis of DHBV across BeWo monolayers. DHBV was added to the apical pole of membrane-grown polarized BeWo monolayers. Virus titer was determined by quantitative PCR. (A) BeWo monolayers were placed at 4°C, and transcytosis was measured for 2 h. Cells were transferred to 37°C, and samples were taken for a further 2 h. Diffusion of [3H]inulin (circles) was also calculated. DHBV transcytosis (squares) is inhibited at 4°C and recommences upon warming of the cells, implying that an active cellular process is required. By contrast, inulin diffusion is constant and temperature independent. (B) Transcytosis of DHBV before (black bars) and after (grey bars) the addition of drugs. DHBV was transcytosed by BeWo cells and was affected by drugs similarly to HBV. DHBV apparently traffics by the same route as HBV. *, P < 0.02 (compared to no drug).

Transcytosed virus is infectious.

The internal pH of transcytotic endosomes is acidic (around pH 5), promoting fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes and thus releasing the virus into the cytosol. HBV is an enveloped virus, and envelopment is necessary for its infectivity (57); thus, it was possible that endocytosis of the HBV in BeWo cells would inactivate the virus. In order to determine whether viral DNA transcytosing through the BeWo monolayer consisted of infectious virus particles, we utilized DHBV as an infectious model of HBV. DHBV is very similar to HBV in structure and protein functions (49) and has almost identical replication cycles (34). Like all members of the hepadnavirus family, it is a hepatotropic, species-specific virus. In the absence of a readily available infectible cell culture system for HBV, DHBV serves as an excellent and well-characterized infectious model (47).

Polarized BeWo cell monolayers grown on semipermeable membranes were examined for DHBV transcytosis by PCR and by infectious virus titer determined on virus-naïve primary duck hepatocytes. As described above, virus was added to cells apically, and each monolayer was treated with trafficking inhibitors or with no drug.

DHBV transcytosed across the BeWo monolayer with efficiency similar to that of HBV, and its passage was likewise affected by transcytosis inhibitors. Virus transcytosis was inhibited by monensin and colchicine similarly, suggesting that the endosomes inhibited by monensin were reliant on microtubular function (Fig. 2A). We thus determined that DHBV was a suitable model for examining the transcytosis of infectious HBV in BeWo cells.

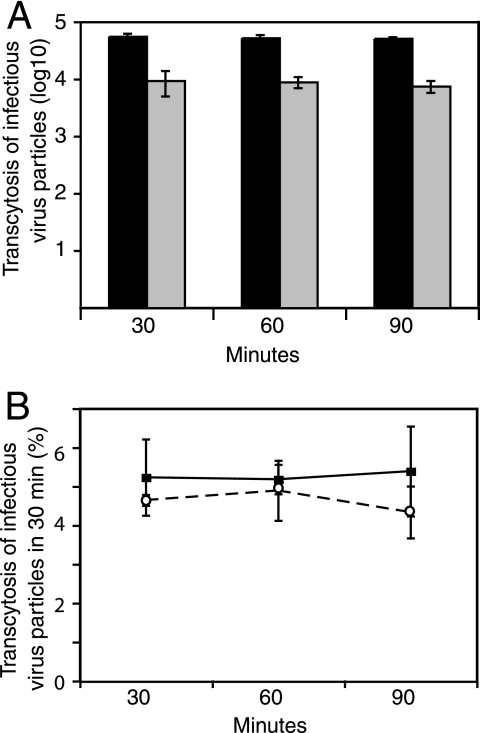

Infection of PDH with basolateral supernatant from BeWo monolayers showed that transcytosis of DHBV through trophoblasts does not affect its infectivity. Infectious hepadnavirus transcytosed across BeWo monolayers at 3 to 5% per 30 min (Fig. 3A). The infective viral titer was about 10-fold less than total DNA by PCR, but the percentage of transcytosis remained the same, indicating that the virus had not been altered by its passage through the BeWo cells (Fig. 3A). As both human and duck HBVs were transported across human trophoblastic cells, it is likely that the pathway used by the viruses is not host species or cell type specific.

FIG. 3.

Transcytosed virus is infectious. Transcytosed DHBV was used to infect PDH in serial dilution to determine infectious virus titer by focus counting. (A) Actual virus titers in the basolateral supernatant are given. Note the logarithmic scale. There is about 10-fold-less infectious virus (gray bars) than total DNA (black bars), but the proportions transcytosed remain the same. (B) Infectious DHBV particles (circles) transcytose at approximately the same rate as total DNA (squares) measured by PCR, 3 to 5% in 30 min.

Hepadnaviral traffic in BeWo cells.

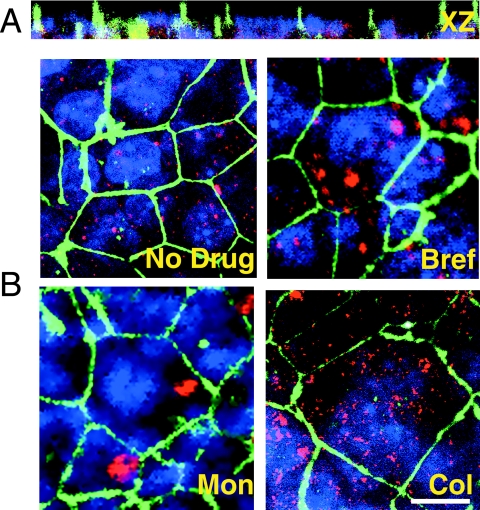

The inhibition of viral transport with the various agents described above suggested that a specific transcytotic route was taken by HBV in BeWo cells. In order to differentiate the patterns of intracellular virus distribution, cell monolayers used in the experiments described above were fixed and stained for ZO-1 and DHBV for examination by confocal microscopy.

The BeWo cells were a single cell layer, with no overgrowth and with tight junctions between the cells in a honeycomb pattern characteristic of polarized epithelia (Fig. 4A). DHBV immunostaining was visible at the level of the tight junctions, indicating the presence of the virus at the apical surface. The cytoplasmic distribution of the virus suggested accumulation in vesicular structures (Fig. 3B). We notably did not see a perinuclear Golgi pattern of distribution of virus in brefeldin A-treated cells, indicating that viral transport in BeWo cells occurs independently of the Golgi and is likely via the transcytotic pathway (Fig. 3B) (27, 60). Monensin treatment led to virus localizing to an area close to the apical surface of the cells (Fig. 3B). This is probably the subapical compartment (SAC), described for other epithelial cells as a sorting center directing newly endocytosed substances to their plasma membrane destinations (53). Also of note in the monensin-treated cells is that there seems to have been minimal viral entry after the addition of the drug, as very little cytoplasmic virus is evident. Colchicine treatment led to cytoplasmic, widely distributed accumulation of virus intracellularly (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that hepadnavirus traffics from the apical surface to the SAC of BeWo cells in microtubule-dependent endosomal vesicles before traveling to the basolateral surface and without recourse to the Golgi, strongly suggestive of transcytosis as the mechanism of transcellular transport.

FIG. 4.

Hepadnavirus traffic in BeWo cells. BeWo monolayers used in the experiments reported in Fig. 2A were fixed in paraformaldehyde and stained for DHBV pre-S antigen (red) and ZO-1 (green). Nuclei are blue. BeWo cells form a confluent, tight, polarized monolayer. (A) xz images show BeWo nuclei in a single layer. (B) In untreated BeWo cells (No Drug), intracellular DHBV is in vesicular structures. Treatment with brefeldin A (Bref) did not result in accumulation of the virus in a typical Golgi pattern. Monensin (Mon) treatment led to virus accumulation in a discrete, subapical, non-Golgi area of the cell, most likely the SAC. Little virus is seen elsewhere in the cell. Endocytosis of further virus appears to have been inhibited by monensin. Colchicine (Col)-induced disruption of microtubules inhibits endosomal transport, resulting in scattered virus throughout the cell. Bar, 10 μm.

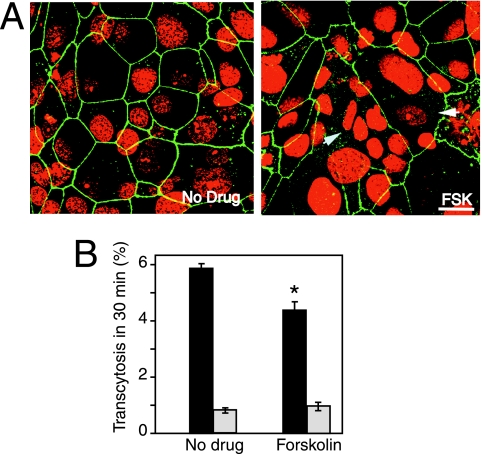

HBV transcytosis is inhibited by cellular differentiation.

With placental development, trophoblasts differentiate and fuse into multinucleated cells that form the syncytiotrophoblast. The formation of this continuous barrier has been associated with reduced viral transmission in some in vitro studies (40, 41). We stimulated differentiation of BeWo cells with forskolin, a potent inducer of cAMP (48). With differentiation, cells fuse as they divide; however, terminally differentiated cells will not further divide. Balancing these effects of cell maturation, we generated cell monolayers that remained contiguous but contained a significant proportion of terminally differentiated syncytiotrophoblasts. We then added HBV to the apical medium, and basolateral collections were taken at 30-min intervals over several hours. [3H]inulin diffusion studies ascertained the integrity of the monolayers. Cells were then fixed, and intracellular tight junctions were stained with ZO-1 before examination by confocal microscopy to determine the percentage of cell fusion.

Confocal microscopy revealed fusion of 3 to 10 cells within a single cell boundary in cultures treated with forskolin (Fig. 5A). We determined a fusion rate of 21.0% (± 0.7%) in treated cells. That is, on average, more than a fifth of the cells were multinucleated. These monolayers did not transcytose virus as effectively as untreated cells, resulting in a small but statistically significant inhibition of transcytosis compared to the untreated BeWo cells. Monolayers displaying differentiation transcytosed only 4.4% of apically applied virus, compared to 5.9% in undifferentiated cells (P = 0.0168) (Fig. 5B). This is a reduction in the rate of transcytosis of around 24%, close to the cell fusion rate of 21%. The reciprocity between reduced viral transport and cell fusion suggests that they are related. Differentiation of the BeWo monolayer from mononuclear cells with tight junctions to partial syncytiotrophoblast formation resulted in significant and proportional reduction in transcytosis.

FIG. 5.

Syncytiotrophoblast formation inhibits transcytosis. BeWo cells were grown to confluence on membranes in the presence of forskolin. Fixed membranes were stained for ZO-1 (green). Nuclei are red. (A) Untreated cells (No Drug) display honeycomb ZO-1 staining of mononucleated BeWo cells; 21.0% (± 0.7%) of forskolin (FSK)-treated cells fused to form multinucleated cells (arrows). Bar, 10 μm. (B) Transcytosis of HBV across the differentiated monolayer was assessed, and virus titer was determined by quantitative PCR. The presence of differentiated cells in the monolayer significantly reduced transcytosis of HBV (black bars) (*, P < 0.02). Inulin diffusion (gray bars) was not affected by cellular differentiation.

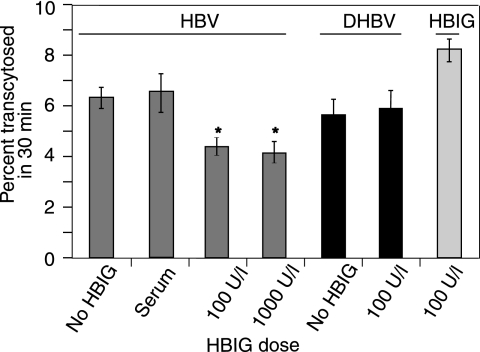

HBIG prevents HBV transcytosis.

Antibodies against HBV surface antigens are protective against disease. The presence of high levels of HBV-specific antibody in infected mothers may affect fetal infection. The effect of HBIG on the transcytosis of HBV was studied. We used doses of HBIG based on minimum target serum concentrations of antibody in liver transplant patients receiving HBIG: approximately 100 mg/liter (10, 21, 29). HBIG treatment at both 100 mg/liter and 1,000 mg/liter reduced HBV transcytosis by a modest but significant degree compared to untreated cells and antibody-negative serum (P = 0.024) (Fig. 6). The addition of 10 times more HBIG, however, caused little additional reduction in transcytosis (P = 0.71). The specificity of the action of the antibody was determined by examining DHBV transcytosis in the presence of HBIG. HBV, but not DHBV, translocation was inhibited by HBIG (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Effect of HBIG on transcytosis. BeWo cells were grown on semipermeable membranes in the presence of HBIG for 72 h before the addition of virus to the apical domain. Viral titers were determined by quantitative PCR. Separately, HBIG alone was added to the apical pole of BeWo monolayers to assess Ig transcytosis. HBIG significantly reduced the transcytosis of HBV. This effect was not dose dependent in this range. Values of significance are given in comparison to untreated controls (*, P < 0.025). HBIG had no effect on the transportation of DHBV. HBIG itself was highly transcytosed by BeWo cells.

Trophoblasts and BeWo cells are known to actively transport IgG via the Fc receptor (12). In order to confirm that BeWo cells were able to transcytose HBIG in this model, we added HBIG to the apical domain of membrane-grown BeWo cells and assayed the apical and basolateral supernatants for IgG by ELISA. We found that BeWo cells transport 8% of apically applied HBIG every 30 min (Fig. 6). This is a very high rate of transcytosis and probably represents both active transport of the molecule and a response to a high apical load of substrate.

It is likely that HBV formed complexes with Ig that were saturated at 100 mg/liter, resulting in no further effect from 1,000 mg/liter of HBIG. The resultant virus-Ig complex may have transcytosed at a reduced rate in these very actively transporting cells. Thus, although we are able to detect viral DNA by PCR in the basolateral domain, it is unclear whether, in fact, this represents free virus and whether it remains infectious.

DISCUSSION

Although perinatal transmission accounts for up to 30% of the carrier pool of HBV (19), very little is known about the mechanism of viral transmission. Neonatal infection was common until the introduction of widespread targeted and universal HBV immunization of infants (59). The global initiative to introduce world-wide vaccination programs will reduce the number of chronically HBV-infected people, but vaccine failure rates are not insignificant. The factors determining vaccination failure, including in utero HBV transmission, remain unresolved.

Maternal-fetal transmission of a number of viruses by transcytosis or infection of the placenta has been described. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission requires infected lymphocytes to transmit virus by direct cell-to-cell contact with the epithelial surface (3, 23). Unlike HIV and human T-cell lymphotropic virus, however, which also readily cross BeWo cells (23, 28), free HBV was able to enter these cells without requiring cell association. In fact, free HIV can enter trophoblasts, but endocytosis leads to degradation of the virus rather than transcytosis (54). Although trophoblasts are permissive for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in vitro, modification of the virus in uterine endothelial cells may be a requirement for infection (13, 31). Replicating CMV also remains largely in the cell, with some release through the apical, but not the basolateral, surface (17), thus further protecting the fetus. By contrast, this study showed that transcytosis of infectious DHBV across placental trophoblasts occurred without change to its specific infectivity, and the same is thus likely to be true for HBV, which showed very similar levels of transcytosis.

HBV entry most likely occurs by endosomal uptake at the apical surface, and its temperature dependence suggests strongly that it is an active process. Also, the rapid increase in internalization upon warming from 4°C to 37°C is highly reminiscent of receptor-mediated internalization. HIV has been shown to travel through apical recycling endosomes to the basolateral pole (54, 55). HBV appears to be transported from the apical plasma membrane in microtubule-dependent endosomes to a subapically located site in the cell that is also sensitive to monensin, likely the common endosome or SAC, described for other polarized epithelial cells as a sorting center for substrates. The dependence on microtubules is characteristic of SAC-dependent, Golgi-independent trafficking (18). Infectious virus is subsequently released from the basolateral surface of trophoblasts into the fetal circulation.

At around 12 weeks of gestation, trophoblasts fuse and differentiate into multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts. We found that a mixed population of cells did not transcytose virus as effectively as a monolayer of undifferentiated cells. This may be due to changes in BeWo cellular protein expression accompanying maturation that reduced virus attachment and transport (33, 35, 39, 43). As transport of molecules across the maternal-fetal barrier must continue to take place throughout pregnancy, it is likely that specific cell factors play a role in HBV transport and that these change with cellular differentiation.

Maternal IgG protects the infant by its active transcytosis across the placenta (11, 12). In some viral infections, such as CMV and herpes simplex virus, the presence of maternal antibodies is significant in protecting the fetus (14, 46). In others, such as HIV, no identifiable protective antibodies have been isolated to date. In Epstein-Barr virus infection, transmission to the fetus may actually be enhanced by antibody-mediated viral entry (16). The presence of maternal α-HBc has been associated with lower levels of perinatal transmission of HBV (6). In addition, HBIG treatment of newborn infants helps prevent transmission, underlying the role of passive immunity in preventing disease acquisition. In our study, HBIG transcytosed actively in BeWo cells. HBIG treatment of cells also significantly and specifically reduced the rate of HBV transcytosis and may have reduced its infectivity. The presence of protective maternal antibodies transcytosing across the maternal-fetal barrier with infectious virus may be one mechanism limiting viral transmission in utero. Conversely, insufficient maternal antibody levels may predispose to HBV transmission during pregnancy.

In determining the factors that contribute to mother-infant HBV transmission, the role of fetal development should be considered. The fetus does not begin to develop a liver until around 12 weeks of gestation (37). It is not known at what stage the development of the functional enhancers and promoters that allow the exclusively hepatotropic HBV to infect hepatocytes takes place. We have shown that while HBV can cross the pre-12-week maternal-fetal barrier, it appears that this is less likely with trophoblast differentiation in later gestation. Fetal hepatic immaturity may be how the fetus remains protected from HBV; this possibility goes somewhat toward explaining the efficacy of HBIG and HBV immunization at birth in preventing infection.

This study addresses some key points regarding maternal-fetal transmission of HBV. The virus is able to cross trophoblastic cells using the endosomal transport system and to remain infectious. The high permeability of undifferentiated trophoblasts to viral transcytosis suggests that early pregnancy is a potentially high-risk period for viral transmission. Finally, these studies suggest that some vaccine failures may represent infections acquired in utero through transcytosis of HBV across the placenta, and they propose one mechanism for mother-infant transmission.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Project Grant and a Senior Research Fellowship (D.A.A.) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

We thank Elizabeth Grgacic for assistance with primary duck hepatocytes.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, D. A., E. V. Grgacic, C. A. Luscombe, X. Gu, and R. Dixon. 1997. Quantification of infectious duck hepatitis B virus by radioimmunofocus assay. J. Med. Virol. 52:354-361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley, R. P., L. Y. Hwang, G. C. Lee, C. C. Lan, C. H. Roan, F. Y. Huang, and C. L. Chen. 1983. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet ii:1099-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bomsel, M. 1997. Transcytosis of infectious human immunodeficiency virus across a tight human epithelial cell line barrier. Nat. Med. 3:42-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burk, R., L. Hwang, G. Ho, D. Shafritz, and R. Beasley. 1994. Outcome of perinatal hepatitis B virus exposure is dependent on maternal virus load. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1418-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerneus, D. P., and A. van der Ende. 1991. Apical and basolateral transferrin receptors in polarized BeWo cells recycle through separate endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 114:1149-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, M. H., H. Y. Hsu, L. M. Huang, P. I. Lee, H. H. Lin, and C. Y. Lee. 1996. The role of transplacental hepatitis B core antibody in the mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. J. Hepatol. 24:674-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien, R. N., Y. F. Liaw, T. C. Chen, C. T. Yeh, and I. S. Sheen. 1998. Efficacy of thymosin alpha 1 in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 27:1383-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Canho, R., P. M. Grosheide, S. W. Schalm, R. R. de Vries, and R. A. Heijtink. 1994. Failure of neonatal hepatitis B vaccination: the role of HBV-DNA levels in hepatitis B carrier mothers and HLA antigens in neonates. J. Hepatol. 20:483-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dentinger, C. M., B. J. McMahon, J. C. Butler, C. E. Dunaway, C. L. Zanis, L. R. Bulkow, D. L. Bruden, O. V. Nainan, M. L. Khristova, T. W. Hennessy, and A. J. Parkinson. 2005. Persistence of antibody to hepatitis B and protection from disease among Alaska natives immunized at birth. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:786-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Paolo, D., G. Tisone, P. Piccolo, I. Lenci, S. Zazza, and M. Angelico. 2004. Low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin given “on demand” in combination with lamivudine: a highly cost-effective approach to prevent recurrent hepatitis B virus infection in the long-term follow-up after liver transplantation. Transplantation 77:1203-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellinger, I., A. Rothe, M. Grill, and R. Fuchs. 2001. Apical to basolateral transcytosis and apical recycling of immunoglobulin G in trophoblast-derived BeWo cells: effects of low temperature, nocodazole, and cytochalasin D. Exp. Cell Res. 269:322-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellinger, I., M. Schwab, A. Stefanescu, W. Hunziker, and R. Fuchs. 1999. IgG transport across trophoblast-derived BeWo cells: a model system to study IgG transport in the placenta. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:733-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher, S., O. Genbacev, E. Maidji, and L. Pereira. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus infection of placental cytotrophoblasts in vitro and in utero: implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 74:6808-6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler, K., S. Stagno, and R. Pass. 2003. Maternal immunity and prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA 289:1008-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs, R., and I. Ellinger. 2004. Endocytic and transcytotic processes in villous syncytiotrophoblast: role in nutrient transport to the human fetus. Traffic 5:725-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan, Y., J. Chodosh, A. Morgan, and J. Sixbey. 1997. Epithelial cell polarization is a determinant in the infectious outcome of immunoglobulin A-mediated entry by Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 71:519-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmings, D., and L. J. Guilbert. 2002. Polarized release of human cytomegalovirus from placental trophoblasts. J. Virol. 76:6710-6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoekstra, D., D. Tyteca, and S. van Ijzendoorn. 2004. The subapical compartment: a traffic center in membrane polarity development. J. Cell Sci. 117:2183-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou, J., Z. Liu, and F. Gu. 2005. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2:50-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunziker, W., J. A. Whitney, and I. Mellman. 1991. Selective inhibition of transcytosis by brefeldin A in MDCK cells. Cell 67:617-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karasu, Z., T. Ozacar, M. Akyildiz, T. Demirbas, C. Arikan, A. Kobat, U. Akarca, G. Ersoz, F. Gunsar, Y. Batur, M. Kilic, and Y. Tokat. 2004. Low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin and higher-dose lamivudine combination to prevent hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Antivir. Ther. 9:921-927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koi, H., J. Zhang, A. Makrigiannakis, S. Getsios, C. MacCalman, J. R. Strauss, and S. Parry. 2002. Syncytiotrophoblast is a barrier to maternal-fetal transmission of herpes simplex virus. Biol. Reprod. 67:1572-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagaye, S., M. Derrien, E. Menu, C. Coito, E. Tresoldi, P. Mauclere, G. Scarlatti, G. Chaouat, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and M. Bomsel. 2001. Cell-to-cell contact results in a selective translocation of maternal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies across a trophoblastic barrier by both transcytosis and infection. J. Virol. 75:4780-4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, A., H. Ip, and V. Wong. 1978. Mechanisms of maternal-fetal transmission of hepatitis B virus. J. Infect. Dis. 138:668-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewin, S., R. Ribeiro, T. Walters, G. Lau, S. Bowden, S. Locarnini, and A. Perelson. 2001. Analysis of hepatitis B viral load decline under potent therapy: complex decay profiles observed. Hepatology 34:1012-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, H. H., L.-Y. Wang, C.-T. Hu, S.-C. Huang, L.-C. Huang, S. S. J. Lin, Y.-M. Chiang, T.-T. Liu, and C.-L. Chen. 2003. Decline of hepatitis B carrier rate in vaccinated and unvaccinated subjects: sixteen years after newborn vaccination program in Taiwan. J. Med. Virol. 69:471-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lippincott-Schwartz, J., L. Yuan, C. Tipper, M. Amherdt, L. Orci, and R. D. Klausner. 1991. Brefeldin A's effects on endosomes, lysosomes, and the TGN suggest a general mechanism for regulating organelle structure and membrane traffic. Cell 67:601-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, X., V. Zachar, N. Norskov-Lauritsen, G. Aboagye-Mathiesen, M. Zdravkovic, P. Mosborg-Petersen, A. M. Dalsgaard, H. Hager, and P. Ebbesen. 1995. Cell-mediated transmission of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I to human malignant trophoblastic cells results in long-term persistent infection. J. Gen. Virol. 76:167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lok, A. S. F. 2002. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 8:S67-S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low, S. H., S. H. Wong, B. L. Tang, P. Tan, V. N. Subramaniam, and W. Hong. 1991. Inhibition by brefeldin A of protein secretion from the apical cell surface of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 266:729-732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maidji, E., E. Percivalle, G. Gerna, S. Fisher, and L. Pereira. 2002. Transmission of human cytomegalovirus from infected uterine microvascular endothelial cells to differentiating/invasive placental cytotrophoblasts. Virology 304:53-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malawista, S. E., and K. G. Bensch. 1967. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: demonstration of microtubules and effect of colchicine. Science 156:521-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez, F., M. Kiriakidou, and J. F. R. Strauss. 1997. Structural and functional changes in mitochondria associated with trophoblast differentiation: methods to isolate enriched preparations of syncytiotrophoblast mitochondria. Endocrinology 138:2172-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason, W. S., G. Seal, and J. Summers. 1980. Virus of Pekin ducks with structural and biological relatedness to human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 36:829-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massabbal, E., S. Parveen, D. Weisoly, D. Nelson, S. Smith, and M. Fant. 2005. PLAC1 expression increases during trophoblast differentiation: evidence for regulatory interactions with the fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7) axis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 71:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melby, E. L., K. Prydz, S. Olsnes, and K. Sandvig. 1991. Effect of monensin on ricin and fluid phase transport in polarized MDCK cells. J. Cell Biochem. 47:251-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore, K., and T. Persaud. 2003. The developing human: clinically oriented embryology, 7th ed. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA.

- 38.Ngui, S. L., N. J. Andrews, G. S. Underhill, J. Heptonstall, and C. Teo. 1998. Failed postnatal immunoprophylaxis for hepatitis B: characteristics of maternal hepatitis B virus as risk factors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:100-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogura, K., M. Sakata, Y. Okamoto, Y. Yasui, C. Tadokoro, Y. Yoshimoto, M. Yamaguchi, H. Kurachi, T. Maeda, and Y. Murata. 2000. 8-Bromo-cyclic AMP stimulates glucose transporter-1 expression in a human choriocarcinoma cell line. J. Endocrinol. 164:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parry, S., J. Holder, M. W. Halterman, M. D. Weitzman, A. R. Davis, H. Federoff, and J. R. Strauss. 1998. Transduction of human trophoblastic cells by replication-deficient recombinant viral vectors: promoting cellular differentiation affects virus entry. Am. J. Pathol. 152:1521-1529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parry, S., J. Holder, and J. Strauss. 1997. Mechanisms of trophoblast-virus interaction. J. Reprod. Immunol. 37:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pugh, J. C., Q. Di, W. S. Mason, and H. Simmons. 1995. Susceptibility to duck hepatitis B virus infection is associated with the presence of cell surface receptor sites that efficiently bind viral particles. J. Virol. 69:4814-4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao, R., S. Rama, and A. Rao. 2003. Changes in t-plastin expression with human trophoblast differentiation. Reprod. Biomed. Online 7:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Red-Horse, K., Y. Zhou, O. Genbacev, A. Prakobphol, R. Foulk, M. McMaster, and S. J. Fisher. 2004. Trophoblast differentiation during embryo implantation and formation of the maternal-fetal interface. J. Clin. Investig. 114:744-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roingeard, P., A. Diouf, J. L. Sankale, C. Boye, S. Mboup, F. Diadhiou, and M. Essex. 1993. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus in Senegal, West Africa. Viral Immunol. 6:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rouse, D. J., and J. S. Stringer. 2000. An appraisal of screening for maternal type-specific herpes simplex virus antibodies to prevent neonatal herpes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 183:400-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz, U., E. Grgacic, and M. Nassal. 2004. Duck hepatitis B virus: an invaluable model system for HBV infection. Adv. Virus Res. 63:1-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seamon, K. B., W. Padgett, and J. W. Daly. 1981. Forskolin: unique diterpene activator of adenylate cyclase in membranes and in intact cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:3363-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sprengel, R., C. Kuhn, H. Will, and H. Schaller. 1985. Comparative sequence analysis of duck and human hepatitis B virus genomes. J. Med. Virol. 15:323-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sprinzl, M., H. Oberwinkler, H. Schaller, and U. Protzer. 2001. Transfer of hepatitis B virus genome by adenovirus vectors into cultured cells and mice: crossing the species barrier. J. Virol. 75:5108-5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun, Z., L. Ming, X. Zhu, and J. Lu. 2002. Prevention and control of hepatitis B in China. J. Med. Virol. 67:447-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchida, T., K. Suzuki, Y. Okuda, and T. Shikata. 1988. In vitro transmission of duck hepatitis B virus to primary duck hepatocyte cultures. Hepatology 8:760-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Ijzendoorn, S. C., and D. Hoekstra. 1999. The subapical compartment: a novel sorting centre? Trends Cell Biol. 9:144-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vidricaire, G., M. Imbeault, and M. J. Tremblay. 2004. Endocytic host cell machinery plays a dominant role in intracellular trafficking of incoming human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human placental trophoblasts. J. Virol. 78:11904-11911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vidricaire, G., and M. J. Tremblay. 2005. Rab5 and Rab7, but not ARF6, govern the early events of HIV-1 infection in polarized human placental cells. J. Immunol. 175:6517-6530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, C.-Y. J., J. J. Giambrone, and B. F. Smith. 2002. Development of viral disinfectant assays for duck hepatitis B virus using cell culture/PCR. J. Virol. Methods 106:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei, Y., J. E. Tavis, and D. Ganem. 1996. Relationship between viral DNA synthesis and virion envelopment in hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 70:6455-6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wice, B., D. Menton, H. Geuze, and A. L. Schwartz. 1990. Modulators of cyclic AMP metabolism induce syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 186:306-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong, V. C., H. M. Ip, H. W. Reesink, P. N. Lelie, E. E. Reerink-Brongers, C. Y. Yeung, and H. K. Ma. 1984. Prevention of the HBsAg carrier state in newborn infants of mothers who are chronic carriers of HBsAg and HBeAg by administration of hepatitis-B vaccine and hepatitis-B immunoglobulin. A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet i:921-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wood, S. A., J. E. Park, and W. J. Brown. 1991. Brefeldin A causes a microtubule-mediated fusion of the trans-Golgi network and early endosomes. Cell 67:591-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, D. Z., Y. P. Yan, B. C. Choi, J. Q. Xu, K. Men, J. X. Zhang, Z. H. Liu, and F. S. Wang. 2002. Risk factors and mechanism of transplacental transmission of hepatitis B virus: a case-control study. J. Med. Virol. 67:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao, J. L. 1996. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection and vaccination in China. Gut. 38(Suppl. 2):S37-S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, S.-L., Y.-F. Yue, G.-Q. Bai, L. Shi, and H. Jiang. 2004. Mechanism of intrauterine infection of hepatitis B virus. World J. Gastroenterol. 10:437-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu, Q., Q. Lu, S. Xiong, H. Yu, and S. Duan. 2001. Hepatitis B virus S gene mutants in infants infected despite immunoprophylaxis. Chinese Med. J. 114:352-354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]