Abstract

Heat-resistant mutants selected from infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses have determinative mutations in the major outer-capsid protein μ1. Here we report the isolation and characterization of intragenic pseudoreversions of one such thermostabilizing mutation. From a plaque that had survived heat selection, a number of viruses with one shared mutation but different second-site mutations were isolated. The effect of the shared mutation alone or in combination with second-site mutations was examined using recoating genetics. The shared mutation, D371A, was found to confer (i) substantial thermostability, (ii) an infectivity defect that followed attachment but preceded viral protein synthesis, and (iii) resistance to μ1 rearrangement in vitro, with an associated failure to lyse red blood cells. Three different second-site mutations were individually tested in combination with D371A and found to wholly or partially revert these phenotypes. Furthermore, when tested alone in recoated particles, each of these three second-site mutations conferred demonstrable thermolability. This and other evidence suggest that pseudoreversion of μ1-based thermostabilization can occur by a general mechanism of μ1-based thermolabilization, not requiring a specific compensatory mutation. The thermostabilizing mutation D371A as well as 9 of the 10 identified second-site mutations are located near contact regions between μ1 trimers in the reovirus outer capsid. The availability of both thermostabilizing and thermolabilizing mutations in μ1 should aid in defining the conformational rearrangements and mechanisms involved in membrane penetration during cell entry by this structurally complex nonenveloped animal virus.

The infectious virions of nonfusogenic mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus) are nonenveloped icosahedral particles with a two-layered protein capsid encasing a 10-segment double-stranded RNA genome. The outer capsid comprises 200 heterohexamers of proteins μ1 and σ3 (μ13σ33) arranged in a quasi-T=13 (laevo) lattice that is substituted around the 12 icosahedral fivefold axes with the pentameric core-turret protein λ2 (16, 22, 39). The trimeric adhesion protein σ1 protrudes as a long fiber from the top of the λ2 turret (13, 18). During infection, σ3 is degraded by endosomal or intestinal proteases, yielding infectious subvirion particles (ISVPs) with μ1 broadly exposed on the surface (2, 3, 12, 16, 19, 21, 31, 33). Subsequent rearrangement of μ1 to a protease-sensitive and hydrophobic conformer is associated with membrane penetration and delivery of transcriptionally active virus particles into the cytoplasm (7, 8). A similar rearrangement can be promoted in vitro by various means, including heat treatment (7, 24, 25). Thus, the particle form resulting from heat treatment is believed to be similar, if not identical, to the penetration-associated particle form, termed the ISVP* (7, 8, 24, 25).

In the μ1 trimer, each of the μ1 molecules is coiled around the threefold axis by more than 360°. Each molecule folds into four distinct domains: I, II, and III, which are largely α-helical, and IV, which forms a β-barrel at the top of the trimer (22). Mutant virus strains that are resistant to heat or ethanol inactivation exhibit delayed or impaired ISVP→ISVP* conversions (8, 20, 24). These mutants have stabilizing mutations in μ1, located in domains III and IV in the upper portions of the μ1 trimer, near intersubunit contacts either within or between trimers. This, as well as evidence from engineered virus particles with disulfide bridges that lock the top domains together within each trimer (38), has led to the proposal that ISVP→ISVP* conversion requires unwinding at the top of the trimer (8, 22, 24, 38). Rearrangement must also translate to the bottom portions of μ1, however, to allow cleavage and release of the N-terminal myristoylated fragment μ1N, which appears to be required for membrane penetration (1, 22, 29, 30). The postconversion structure of the particle-associated μ1 fragment(s) remains unknown.

In an initial study of reovirus heat-resistant (HR) mutants selected by heat inactivation of ISVPs, several were found to have two amino acid substitutions in the μ1 protein, but the relative effect of each of these changes was not addressed experimentally (24). In the current report, we demonstrate that at least one of these “double” mutants arose from an initial plaque that contained viruses with one shared mutation but a number of different second-site mutations. To test the hypothesis that the second-site mutations represent different intragenic pseudoreversions of the shared mutation, the effects of the two mutations were examined alone and in combination using recoating genetics (9, 10). The results provide further evidence that inactivation-resistant mutants are useful reagents for exploring the molecular basis of reovirus outer-capsid stability, as well as the conformational rearrangements and mechanisms involved in membrane penetration during cell entry by this nonenveloped animal virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Spinner-adapted mouse L929 cells were grown in Joklik's modified minimal essential medium (Irvine Scientific) supplemented to contain 2% fetal bovine and 2% bovine calf sera (HyClone) in addition to 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Irvine Scientific). Spodoptera frugiperda clone 21 and Trichoplusia ni TN-BTI-564 (High Five) insect cells (Invitrogen) were grown in TC-100 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented to contain 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

Virus stocks.

Virions were grown in spinner cultures of murine L929 cells, purified according to the standard protocol (18), and stored in virion buffer (VB; 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) at 4°C. Purified cores for use in recoating were prepared from type 1 Lang (T1L) virions as described elsewhere (9), except that virions were digested with 250 μg/ml chymotrypsin for 2 to 4 h. Particle concentrations were estimated by A260 (15) or by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Cell lysate stocks were grown in L929 cell monolayers, harvested by two rounds of freezing and thawing, and stored at 4°C.

Isolation of new double mutants.

As described by Middleton et al. (24) and as diagrammed in Fig. 1, the first plaque of HR mutant IL54-5 was grown into passage 1 and 2 (P1 and P2) stocks before being subjected to further plaque purifications and amplifications to yield cell lysate stocks of IL54-5-a, which gave rise to the previously reported M2 sequence of this clone. For the current study, the initial P1 stock was reused for picking 33 new plaques of various sizes (Fig. 1), each into 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (137 mM NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl [pH 7.5]) supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 (PBS-Mg). The picked suspension of each of these new plaques was then frozen and thawed twice and directly used for replaquing. These new plaques were grown into new P1 and P2 stocks (Fig. 1) by the methods described previously (24), and the P2 stocks were then used for M2 sequence determinations as described below.

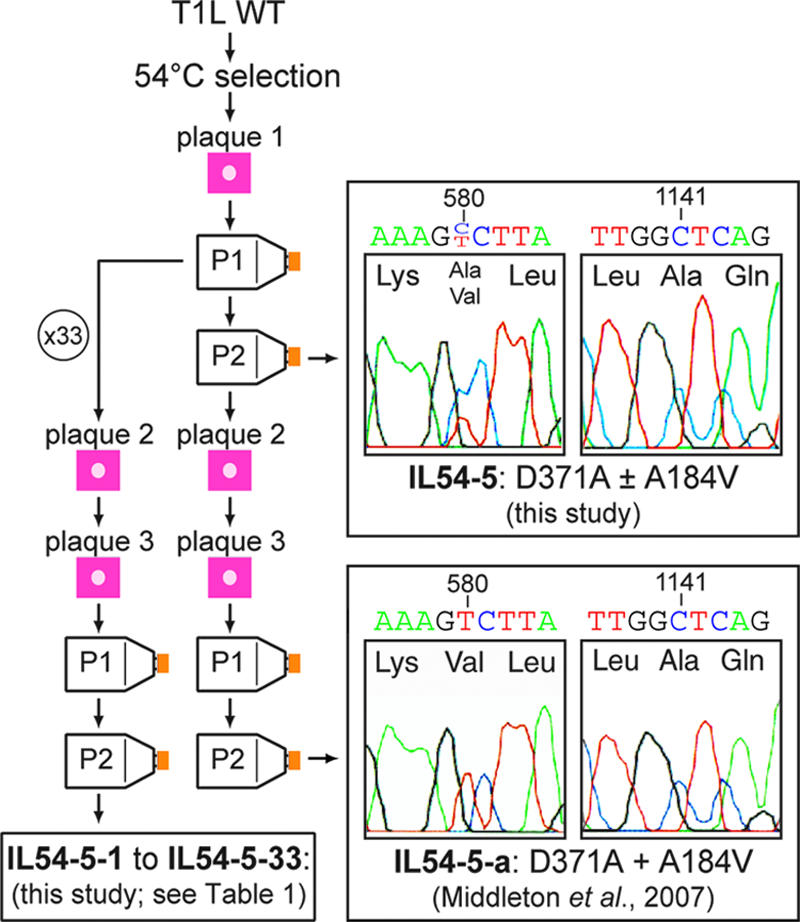

FIG. 1.

Diagram of virus clone and virus stock origins and portions of M2 DNA-sequencing electropherograms of the initial, mixed stock of HR mutant IL54-5 and of the previously characterized HR mutant clone IL54-5-a (24). The IL54-5 stock contains a C+T mixture at nucleotide position 580, encoding a mixture of A184 and A184V. Both IL54-5 and IL54-5-a have a C at nucleotide position 1141, encoding D371A.

Sequencing.

The initial P2 stock of HR mutant IL54-5 was used to infect cells for obtaining purified virions. Cores were derived from the virions and used to generate plus-strand transcripts; these transcripts were then amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), followed by sequencing of the M2 gene (Fig. 1) by the methods described previously (24). For sequencing from infected-cell lysates of the 33 new clones of IL54-5 described above, 2.4 × 106 L929 cells were infected with P2 stock at a multiplicity of 1 or 0.1 PFU/cell. At 19 h postinfection (p.i.), total RNA was harvested using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Plus-strand transcripts were reverse-transcribed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and PCR amplified with Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen). PCR products were agarose gel purified using a gel purification kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center DNA Resource Core.

RCs.

Recoated cores (RCs) were made with baculovirus-expressed wild-type (WT) T1L σ3, WT T1L σ1, and either WT T1L μ1, WT T3D μ1, or mutant μ1, as described previously (9), with the following changes. Cores were incubated with insect cell lysates for 2 to 15 h to assemble the outer capsid, and RCs were purified by banding on CsCl step gradients (ρ = 1.30 to 1.45 g/cm3). Baculoviruses expressing mutant μ1 were made from the M2 genome segments cloned by RT-PCR as described below. SDS-PAGE and densitometry were used to confirm that RCs contained a full complement of μ1 and σ3.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) as described elsewhere (6). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and detected with rabbit T1L-virion-specific serum (1:1,000) (36), followed by rabbit-specific donkey immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Antibody binding was detected with Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagents (PerkinElmer) and a Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare) in chemiluminescence mode.

Plaque assays.

Chymotrypsin-overlay plaque assays were performed as described elsewhere (24).

Heat inactivation.

For the screening of putative mutants (Fig. 2), chymotrypsin digests of cell lysate stocks were made by diluting stocks 1/10 in VB and treating them with 200 μg/ml Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK)-treated α-chymotrypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. Digestion was stopped by the addition of 2 mM ethanolic phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Chymotrypsin digests were diluted 1/10 in PBS-Mg; half was then subjected to heat treatment at 52°C for 30 min, while the rest was held at room temperature. For heat inactivation of RCs (Fig. 3), ISVP-like particles (pRCs) were obtained by digesting RCs at a concentration of 9 × 1011 or 1 × 1012 particles/ml in VB with 200 μg/ml chymotrypsin for 15 min at 37°C. Digestion was stopped by the addition of 1 mM PMSF and incubation on ice for at least 10 min. Production of ISVPs, including the appropriate cleavage products of μ1, was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. pRCs were diluted to 1 × 1010 particles/ml in cold VB and treated for 15 min at the indicated temperatures or on ice. Samples were removed to an ice bath after heat treatment.

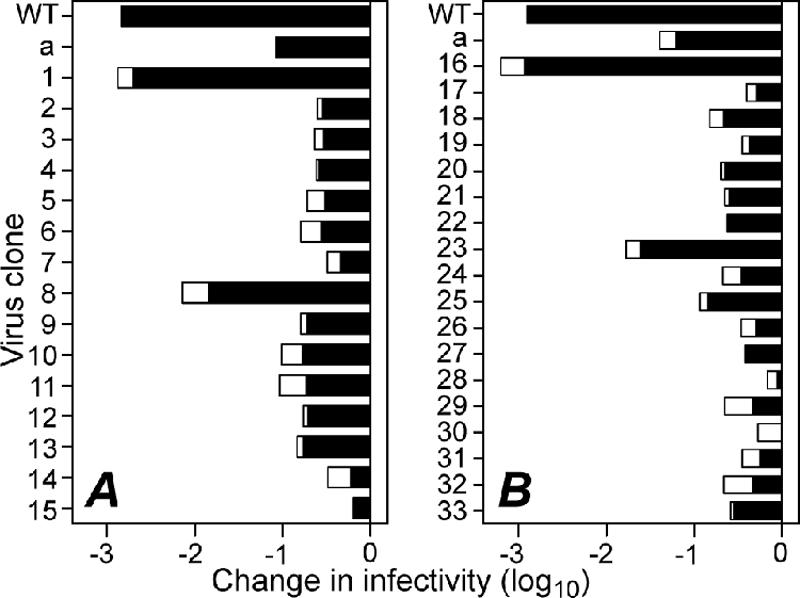

FIG. 2.

Changes in infectivity of reovirus clones after heat treatment of ISVPs at 52°C for 30 min. P2 cell lysate stocks in two separate batches, clones 1 to 15 (A) and 16 to 33 (B), were digested with chymotrypsin to convert virions in the lysates to ISVPs. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to an aliquot of each sample held at room temperature. Results from two independent experiments with each clone are shown as superimposed bars. Stocks of T1L WT and the previously characterized HR mutant clone IL54-5-a were treated and analyzed in parallel with the other clones.

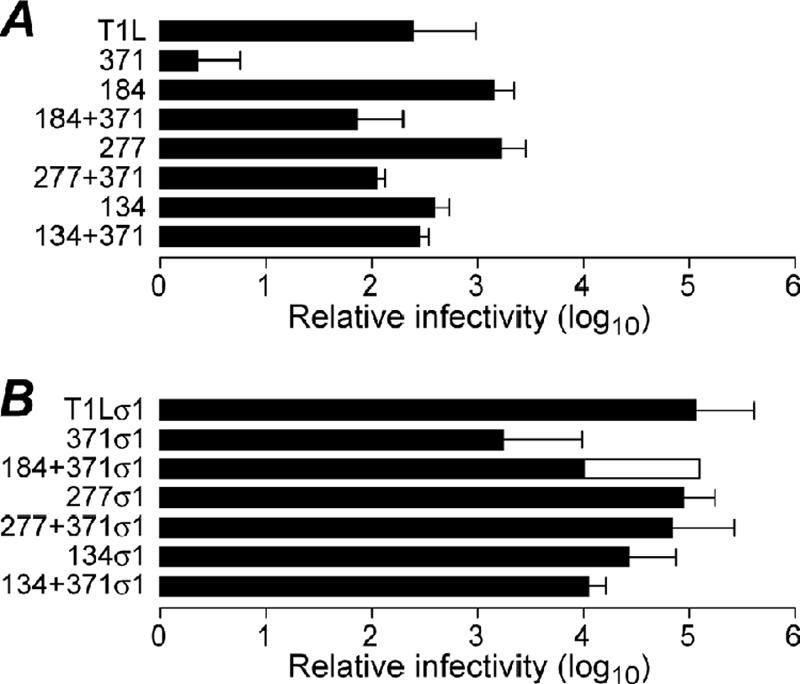

FIG. 3.

Effect of double mutations on thermostability. RCs were made with μ1 protein containing double mutations, or each mutation in isolation, identified from clones IL54-5-a (mutations D371A and A184V) (A); IL54-5-8 (mutations D371A and P277T) (B); IL54-5-16 (mutations D371A and S134L) (C); or ID46-2 (mutations Y431C and T325A) (E) or a combination of mutations from IL62-3 and IL54-5-16 (mutations K459E and S134L) (D). After digestion with chymotrypsin to yield pRCs, virus was subjected to treatment at the indicated temperature for 15 min. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to an aliquot of each sample held on ice. Each point represents the mean of two determinations, except points in parentheses, for which one of the replicates resulted in a titer below the limit of detection.

Flow cytometry.

WT(T1L)-RCs or D371A-RCs containing σ1 were adsorbed at 6 × 104 particles/cell to L929 cells in a 1:1 solution of VB and PBS-Mg for 90 min on ice, with periodic agitation. Cells were then washed twice with cold PBS-Mg and resuspended in media. An aliquot was shifted to 37°C (“infection aliquot”) in a 24-well plate, while the rest (“attachment aliquot”) was fixed immediately in ∼2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min on ice and washed twice in 0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS (PBSA). At 16 h p.i., the infection aliquot was washed gently with PBS, and cells were removed from the plate with trypsin. Cells were collected by centrifugation and fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde as described above. The infection aliquot was permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBSA for 30 min on ice. The attachment aliquot was labeled with the σ3-specific mouse monoclonal antibody 10G10 (35) (1:500) for ∼100 min at room temperature, followed by mouse-specific secondary antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor488 (Invitrogen) for ∼45 min at room temperature. The infection aliquot was labeled as above, except that μNS-specific rabbit serum (1:5,000) (5) and rabbit-specific secondary antibody were used. Labeling was assayed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For each sample, 5,500 to 10,000 events were collected, and histogram heights were normalized to equivalent numbers of events. Data were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) and MFI software (E. Martz, University of Massachusetts, Amherst).

Hemolysis and protease-sensitivity assays.

pRCs were made by digesting RCs at a concentration of 2.5 × 1012 to 5 × 1012 particles/ml in VB with 200 μg/ml chymotrypsin for 10 min at 32°C. For hemolysis experiments including thermolabilizing mutations, pRCs were made instead at 23°C for 15 min. Digestion was stopped by the addition of 1 mM PMSF and incubation on ice for at least 10 min. Hemolysis reactions were performed in VB with 400 mM CsCl. Citrated bovine-calf red blood cells (RBCs; Colorado Serum) were washed immediately before use in PBS-Mg, and reactions were incubated at 37 or 42°C. For time course experiments such as that shown in Fig. 6A, reaction mixtures contained ∼10% (vol/vol) RBCs and 4 × 1012 pRCs/ml, and each time point represents a separate tube, which was removed to an ice bath at the indicated time. Endpoint experiments such as that shown in Fig. 6B contained ∼3% (vol/vol) RBCs and 3.5 × 1012 pRCs/ml. Reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 380 × g for 2 to 5 min to pellet unlysed cells. An aliquot of supernatant was then diluted either 5× or 10× with VB, and absorbance at 405 nm (A405) was measured in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices). The percentage of hemolysis was calculated as [(A405 (sample) − A405 (blank))/(A405 (detergent) − A405 (blank))] × 100%, where the blank reaction mixture contained all components except pRCs and the detergent reaction mixture was the same as the blank, except that it contained 1% Triton X-100. An aliquot of the remaining supernatant was assayed for μ1 conformational change by incubating it with 100 μg/ml trypsin on ice for 45 min, followed by incubation with 300 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor for at least 15 min. Time course experiments such as that shown in Fig. 6C were generated by incubating hemolysis reaction mixtures containing ∼3% (vol/vol) RBCs and 2 × 1012 particles/ml in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices) preequilibrated at 37°C. Absorbance at 650 nm (A650) was measured every 10 s, with a 1-s shake between each read. Relative absorbance was calculated as [(A650 (sample) − A405 (detergent))/(A405 (blank) − A405 (detergent))] × 100%, where the blank and detergent reactions were assembled as described above.

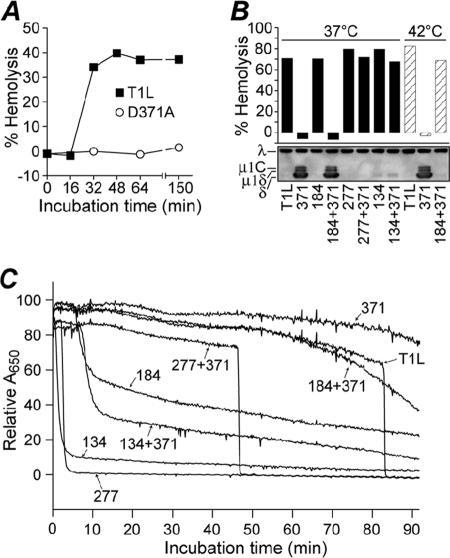

FIG. 6.

Effect of double mutations on hemolysis activity. Chymotrypsin digests of RCs (pRCs) made with μ1 protein containing double mutations, or each mutation in isolation, were mixed with bovine red blood cells and hemolysis buffer and incubated at 37°C, unless indicated otherwise. (A) Representative time course of hemolysis reactions with 4 × 1012 WT- and D371A-pRCs/ml at 37°C. Hemolysis was measured by calculating the A405 after pelleting unlysed cells. (B) Thirty-minute end points of hemolysis reactions with 3.5 × 1012 pRCs/ml at 37°C (filled bars) or 42°C (striped bars). Hemolysis (top) was measured by calculating the A405 after pelleting unlysed cells; means of results from two experiments are shown. Conformational change of μ1 in the hemolysis reactions (bottom) was assayed by trypsin digestion on ice and Western blotting with virion-specific serum. Viral proteins λ and μ1 (present as cleavage products μ1C, μ1δ, and δ) are indicated. A representative result is shown. (C) Time course of hemolysis reactions with 2 × 1012 pRCs/ml at 37°C. Hemolysis was measured by calculating the A650 of whole reactions at 10-second intervals. In this assay, the abrupt reduction in A650 in association with hemolysis reflects the reduced light scattering by lysed cells. A representative experiment is shown.

Molecular graphics.

The crystal structure images in Fig. 7 were created using PyMol v0.95 (DeLano Scientific).

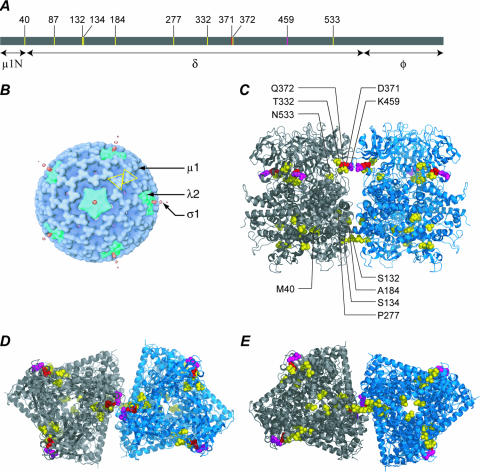

FIG. 7.

(A) The positions of mutations in the primary sequence of T1L μ1 are shown in a line diagram, along with the positions of the δ/φ and μ1N/δ cleavages, which occur during ISVP and ISVP* formation, respectively (28, 29). (B) Locations of μ1, λ2, and σ1 in an electron cryomicroscopy reconstruction of the ISVP (16, 24, 27, 32). Two μ1 trimers related by quasi-twofold symmetry are indicated by yellow outlines. (C through E) Locations of double mutations in the μ1 trimer crystal structure (22) and model of the trimer-trimer interface (39). The two trimers shown are related by quasi-twofold symmetry, analogous to the trimers outlined in panel B. The position of thermostabilizing mutation D371A is shown in red, and that of orthologous thermostabilizing mutation K459E is shown in purple. Second-site mutations are shown in yellow. Views from the side (C), top (D), and bottom (E) are shown.

RESULTS

Descendants of a virus particle that survived heat selection contain different second-site mutations.

In a recent study, Middleton et al. (24) found that three of the nine HR mutants isolated by heat selection from reovirus T1L or T3D ISVPs have two mutations in the major outer-capsid protein μ1. For example, a serially plaque-purified clone of the IL54-5 mutant, which was selected at 54°C and is called IL54-5-a in this report, contains μ1 mutations D371A and A184V. We hypothesized that one of these mutations was selected initially to confer thermostability at 54°C but that it also conferred a growth defect, such that the other mutation was then selected as an intragenic pseudoreversion to restore fitness for growth. In that case, a mixture of progeny viruses with different rescuing pseudoreversions may have arisen within the initial plaque and/or stocks derived directly from it. To test for this possibility, the μ1-encoding M2 gene of purified virions derived from the initial IL54-5 plaque prior to additional plaque purifications was sequenced following RT-PCR amplification of core-derived plus-strand transcripts (Fig. 1). Both of the previously identified mutations, D371A and A184V, were present; however, the population contained a mixture of sequences at amino acid position 184 (nucleotide position 1141), with only about one-third containing the A184V mutation and the remainder being WT (Fig. 1). Inspection of the DNA-sequencing electropherograms did not reveal any other positions with an obvious mixture of sequences. We recognized, nonetheless, that virions containing other secondary mutations may be present in the stock, but at a low enough frequency so as not to have been detected in the population sequence.

To search for virions with other secondary mutations, 33 new clones (IL54-5-1 to IL54-5-33) were isolated from the apparently mixed stock by serial plaque purifications (Fig. 1). Chymotrypsin digests of cell lysate stocks (24) were screened for heat resistance by treatment at 52°C for 30 min (Fig. 2). A range of heat resistance phenotypes was observed, suggesting that at least some of the new clones may contain different secondary mutations that affect the thermostability of ISVPs. M2 genes from the new clones were sequenced after RT-PCR amplification of the viral plus-strand transcripts in infected-cell lysates (Table 1). All of the 33 clones were found to contain the D371A mutation. In addition, each clone was found to contain one other amino acid substitution in μ1: 22 clones contained the same second-site mutation as IL54-5-a, A184V, while the remaining 11 clones contained different second-site mutations. In total, 10 different second-site mutations at 9 different positions in the μ1 sequence were identified. None of the clones contained only the D371A mutation without a second mutation. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that D371A is the initial mutation that granted heat resistance to the original particle that survived the 54°C selection but that it also conferred a growth defect that required either direct reversion (not seen in this set of 33 clones) or pseudoreversion to restore fitness for growth. The frequency with which A184V was found as the second-site mutation among these clones could indicate that it arose early in the formation of the initial IL54-5 plaque and thus had greater opportunity for amplification (23) or that it imparts a fitness advantage relative to other second-site mutations.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of M2 (μ1-encoding) genome segments of new virus clones isolated from IL54-5

| IL54-5 clone(s) | M2 mutationsa | μ1 mutationsb |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A1141C, C1143G | D371A, Q372E |

| 2-7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 18-20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 31-33 | A1141C, C580U | D371A, A184V |

| 8 | A1141C, C858A | D371A, P277T |

| 11, 25 | A1141C, C424U | D371A, S132L |

| 14 | A1141C, G149A | D371A, M40I |

| 15 | A1141C, C859U | D371A, P277L |

| 16 | A1141C, C430U | D371A, S134L |

| 17 | A1141C, A1626G | D371A, N533D |

| 21 | A1141C, C580U, U411Cc | D371A, A184V |

| 23 | A1141C, C289A | D371A, P87Q |

| 28, 30 | A1141C, C1024U | D371A, T332I |

Designations are the nucleotide in the T1L WT M2 sequence, the nucleotide number, and the nucleotide in the mutant M2 sequence.

Deduced from each M2 nucleotide sequence. Designations are the amino acid in the T1L WT μ1 sequence, the amino acid number, and the amino acid in the mutant μ1 sequence.

Silent mutation.

The D371A mutation is thermostabilizing.

To directly test the hypothesis that D371A is the heat resistance mutation, RCs (9, 10) were made containing this mutation alone. These particles, together with RCs made with WT T1L μ1, were next digested with chymotrypsin to yield pRCs that contained the expected fragments of μ1 (9) (see Fig. 6 and data not shown). The pRCs were then subjected to heat treatment at a range of temperatures (Fig. 3A through C). WT-pRCs were found to be inactivated at treatment temperatures between 52 and 54°C, with the titer falling to below detectable levels by 54 or 56°C, as reported previously (24, 25). In contrast, D371A-pRCs remained resistant to inactivation at treatment temperatures up to 62°C, with the titer significantly reduced or below detectable levels after treatment at 64°C. Nearly identical inactivation behavior was observed with pRCs derived from three separate preparations of D371A-RCs (Fig. 3A through C). These results demonstrate that the D371A mutation alone is sufficient to confer substantial thermostability to pRCs.

Second-site mutations counteract D371A-conferred thermostability.

To determine the effect of the second-site mutations, pRCs containing the double mutations from clones IL54-5-a (D371A+A184V), IL54-5-8 (D371A+P277T), and IL54-5-16 (D371A+S134L) were generated. The first of these clones was chosen for analysis because it contains the most common second-site mutation, A184V. The other two clones were chosen because they were substantially inactivated upon treatment of ISVPs at 52°C (Fig. 2), suggesting that these particular second-site mutations have a more pronounced effect on the D371A-conferred thermostability.

When D371A+A184V-pRCs were subjected to heat treatment at a range of temperatures, these particles exhibited a partial degree of heat resistance, less than that of D371A-pRCs but more than that of WT-pRCs (Fig. 3A). These results demonstrate that second-site mutation A184V is sufficient for partial pseudoreversion of the heat resistance phenotype conferred by the D371A mutation. On the other hand, both D371A+P277T-pRCs and D371A+S134L-pRCs failed to exhibit heat resistance but were instead inactivated at temperatures similar to that required for inactivation of WT-pRCs (Fig. 3B and C). These results demonstrate that second-site mutation P277T or S134L is sufficient for approximately complete pseudoreversion of the heat resistance phenotype conferred by the D371A mutation.

Second-site mutations are thermolabilizing.

Since second-site mutations S134L, A184V, and P277T each fully or partially counteracts D371A-conferred thermostability, returning the thermostability of pRCs toward WT levels, we hypothesized that each of these second-site mutations on its own, in the absence of the D371A mutation, may destabilize the μ1 protein in pRCs. To test this hypothesis, pRCs containing each of the mutations alone (A184V-pRCs, P277T-pRCs, and S134L-pRCs) were generated and subjected to heat treatments at a range of temperatures. We were unable to generate A184V-pRCs containing σ1, and as a result, the data for this mutant were generated using pRCs lacking σ1. Previous work has suggested that the presence of σ1 does not affect ISVP stability (9); in addition, WT-pRCs, D371A-pRCs, and A184V+D371A-pRCs with and without σ1 exhibited similar heat inactivation profiles (data not shown). In the cases of the S134L and P277T mutations, the pRCs were dramatically thermolabilized, becoming inactivated at treatment temperatures at least 10°C lower than that required to inactivate WT-pRCs (Fig. 3B and C). In the case of the A184V mutation, the pRCs were also thermolabilized, although not to the extent of the other two second-site mutations, becoming inactivated at treatment temperatures ∼4°C lower than that required to inactivate WT-pRCs (Fig. 3A). In sum, the results described in this and the preceding two sections suggest that the thermostabilizing effect of the primary mutation D371A and the thermolabilizing effect of the secondary mutation S134L, A184V, or P277T are in opposition, largely if not wholly independent, and approximately additive.

Thermolabilizing mutation S134L also counteracts the thermostabilizing mutation K459E.

To address whether the counteracting effects of the thermolabilizing mutations are strictly specific to D371A, pRCs containing S134L and a different thermostabilizing mutation, K459E, were created. The K459E mutation was selected in previous studies for both heat resistance (24) and ethanol resistance (20). As with the D371A mutation, the thermostabilizing effect of K459E was completely reverted by the incorporation of S134L (Fig. 3C). We therefore conclude that the counteracting effects of the thermolabilizing mutation S134L are not strictly specific to D371A. Since D371 and K459 form a salt bridge in the WT T1L μ1 structure (22), it may be that mutations D371A and K459E, which both eliminate the salt bridge, are thermostabilizing through the same basic structural mechanism, in which case it may not be surprising that a pseudoreversion of D371A also counteracts K459E.

A mutation from an independent double mutant is thermolabilizing.

In addition to IL54-5, isolated from reovirus T1L, two other HR mutants with double mutations in μ1 were isolated from reovirus T3D in the initial heat resistance selection (24). These two mutants both contain the mutation Y431C and one other mutation: T325A in mutant ID46-2 and E89Q in mutant ID46-4. Although attempts to obtain RCs with Y431C alone failed for unknown reasons, pRCs were successfully made containing T325A alone or Y431C+T325A in T3D μ1. Heat-inactivation curves (Fig. 3D) revealed that T325A is a thermolabilizing mutation, as pRCs containing this mutation were inactivated at temperatures approximately 8°C lower than pRCs containing WT T3D μ1. However, pRCs containing both T325A and Y431C were inactivated at temperatures similar to those for WT, suggesting that Y431C is a thermostabilizing mutation that is counteracted by T325A.

Thermostabilizing mutation D371A confers an infectivity defect that is reverted by the thermolabilizing mutation S134L, A184V, or P277T.

The observation that D371A is accompanied by a second-site mutation in all of the virus clones that we examined is consistent with the hypothesis that D371A-conferred thermostability also imparts a growth defect, possibly a defect in cell entry due to “overstabilization” of μ1, requiring a secondary destabilizing mutation to improve its fitness for growth. To test this hypothesis, infectivities of RCs were measured by plaque assay and expressed as particle/PFU values relative to those of the cores used for recoating (Fig. 4). Since relative infectivity can be influenced by differential incorporation of the adhesion fiber σ1 during recoating, RCs made both without σ1 (Fig. 4A) and with σ1 (Fig. 4B) were analyzed. WT-RCs without and with σ1 were found to have relative infectivities ∼100-fold and ∼100,000-fold greater than cores, respectively, as reported previously (9, 10). In both cases, D371A-RCs were significantly less infectious than WT-RCs. In contrast, RCs containing both D371A and a second-site mutation, or one of the second-site mutations alone, had infectivities similar to that of WT-RCs. These results suggest that the D371A mutation confers an infectivity defect. Infectivity experiments were scored by counting plaques 2 to 3 days after inoculation, after several cycles of virus replication; however, since the experiments were performed with RCs, which contain mutant μ1 protein but WT genome, any phenotype must result from an effect of the input RC-associated μ1 protein on the first round of replication.

FIG. 4.

Effect of double mutations on infectivity. RCs were made with μ1 proteins containing double mutations, or each mutation in isolation, identified from clones IL54-5-a (thermostabilizing mutation D371A and thermolabilizing mutation A184V), IL54-5-8 (thermostabilizing mutation D371A and thermolabilizing mutation P277T), and IL54-5-16 (thermostabilizing mutation D371A and thermolabilizing mutation S134L). Infectivity was measured by plaque assay, and relative infectivity is expressed as the log10 of the particle/PFU ratio of the RC preparation after subtracting log10 of the particle/PFU ratio of the cores used for recoating. RCs made without σ1 (A) and with σ1 (B) were assayed. A184V-RCs with σ1 are omitted because, for unknown reasons, they could not be generated in several attempts. Error bars indicate the means ± the standard deviations of the results from three or more RC preparations, and overlapping bars represent the results from two RC preparations.

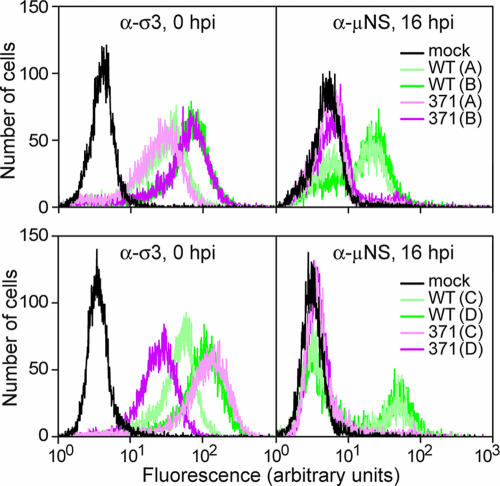

To examine the first round of infection more directly, synthesis of the nonstructural protein μNS was assayed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5). Experiments were performed with four different preparations each of WT-RCs and D371A-RCs. Virus was adsorbed to L929 cells in suspension at 0°C for 90 min, and then cells were washed and resuspended in media. An aliquot was fixed at 0 h p.i. and labeled with σ3-specific antibody to measure attachment (Fig. 5, left panels), and the rest was incubated at 37°C to allow infection to proceed. At 16 h p.i., cells were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with a μNS-specific antibody (Fig. 5, right panels). Although the eight RC preparations exhibited various levels of attachment, two of the D371A-RC preparations had attachment that was at least as good as that of the WT-RC preparations. Nevertheless, none of the D371A-RC preparations yielded significant μNS synthesis by 16 h p.i. These results suggest that D371A-RCs are defective at an early step in infection, after attachment but before viral protein synthesis.

FIG. 5.

Effect of thermostabilizing mutation D371A on viral protein synthesis. L929 cells were adsorbed with WT- or D371A-RCs for 90 min in the cold and then washed. An aliquot was fixed and labeled with σ3 antibody to measure attachment (left panels), and the rest were shifted to 37°C to allow infection to proceed. At 16 h p.i., cells were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with anti-μNS serum (right panels). Samples were labeled with a fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results from four different preparations (A, B, C, and D) of WT- and D371A-RCs, in two experiments (top and bottom), are shown.

Thermostabilizing mutation D371A confers resistance to ISVP* conversion, which is reverted by thermolabilizing mutation S134L, A184V, or P277T.

In previous work on HR mutants, Middleton et al. (24) found that thermostability is associated with resistance to μ1 rearrangement to a protease-sensitive conformer. Protease sensitivity of μ1 is also a hallmark of ISVP* conversion and associated hemolysis activity (7). According to the hypothesis that D371A “overstabilizes” μ1, D371A-pRCs were expected to resist ISVP* conversion and therefore also to be defective at mediating hemolysis. This was confirmed by performing a hemolysis time course with D371A-pRCs and WT-pRCs at 37°C (Fig. 6A). While WT pRCs mediated hemolysis by 32 min in this experiment, D371A-pRCs completely failed to hemolyze for at least 150 min, when the experiment was terminated.

To test the capacity of the second-site mutations to revert the hemolysis defect conferred by D371A, pRCs containing both D371A and a second-site mutation, or a second-site mutation alone, were tested for hemolysis activity (Fig. 6B). After 30 min at 37°C, all except D371A+A184V-pRCs mediated WT-like levels of hemolysis. However, when incubated at 42°C, this mutant was also able to hemolyze, while D371A-pRCs remained defective (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that all three of the second-site mutations tested at least partially revert the hemolysis defect conferred by D371A and are consistent with the observation that although A184V is thermolabilizing, the A184V+D371A double mutant is still more heat resistant than the WT. The conformation of μ1 in the hemolysis reactions was assayed by trypsin digestion on ice (Fig. 6B), and as expected, hemolysis activity was accompanied by μ1 rearrangement to a protease-sensitive conformer in all cases.

Hemolysis time courses with all of the mutants (Fig. 6C) revealed that pRCs containing second-site mutations alone (A184V-pRCs, P277T-pRCs, and S134L-pRCs) undergo very rapid ISVP* conversion, before that of WT-pRCs. Furthermore, the onset of ISVP* conversion mirrors the relative thermolability of these mutations (compare Fig. 6C with Fig. 3A through C). The double mutants P277T+D371A-pRC and S134L+D371A-pRC also exhibit accelerated ISVP* conversion, intermediate between that of WT-pRCs and pRCs containing the respective destabilizing mutations alone. The concentration dependence of the kinetics of ISVP* conversion (4, 7, 26; M. A. Agosto, K. S. Myers, and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data) is evident in the discrepancy in the hemolysis time courses in Fig. 6A and C, which were performed at 4 × 1012 and 2 × 1012 pRCs/ml, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Viruses with 10 different double-mutation M2 genotypes were derived from the plaque of a virus particle that had survived heat selection with ISVPs at 54°C. Each of these viruses contains two amino acid substitutions in the μ1 protein: D371A and a second-site mutation that is located at different positions in different viruses. Using RCs to study the effects of separating the two mutations, D371A was found to confer (i) increased thermostability (Fig. 3), (ii) an infectivity defect that followed attachment but preceded viral protein synthesis (Fig. 4 and 5), and (iii) resistance to μ1 rearrangement (reflecting ISVP* conversion) in vitro, with an associated failure to lyse red blood cells (Fig. 6). Together, these data suggest that the D371A mutation impairs the membrane penetration function of reovirus by impeding μ1 rearrangement.

The three second-site mutations that we tested in RCs were found to revert, in whole or in part, the thermostability, infectivity, and hemolysis phenotypes conferred by D371A (Fig. 3, 4, and 6). The second-site mutation A184V provided partial reversion of the thermostability and ISVP* conversion phenotypes of D371A, whereas the second-site mutations S134L and P277T provided approximately complete reversion of these phenotypes. The observations that IL54-5a (A184V+D371A), as well as several of the other clones, remains more thermostable than WT (Fig. 2 and 3), and that each of the virus clones isolated from the mixed stock has a second-site mutation in μ1, in addition to D371A, suggest that the D371A-conferred infectivity defect is severe enough to give a growth advantage to viruses with pseudoreversions that even partially rescue the heat resistance phenotype of D371A.

The three double mutants tested in RCs appear to have similar infectivities (Fig. 4). However, we have not specifically addressed the relative fitness advantage for growth imparted by the different second-site mutations. As noted in Results, the fact that the A184V mutation was encountered much more frequently than any of the others may indicate that it is more fit for growth but may just as well indicate that it arose early during formation of the initial plaque (23). Repeated passage of the mixed stock of the HR mutant IL54-5 might result in greater amplification of the most fit pseudoreversions and the loss of others. Nevertheless, the fact that each pseudorevertant clone was serially plaque purified and passaged before sequencing suggests that all of them are at least fit enough to be maintained through this degree of amplification in culture.

The different second-site mutations span a large region of μ1 primary sequence, between residues 40 and 533. Eight of the nine positions of second-site mutations are in the central, δ-fragment region of μ1, as is the primary mutation D371A (Fig. 7A). The second-site mutation at residue 40 (M40I), however, is in the N-terminal, μ1N-fragment region of μ1. This is the first direct evidence that the μ1N region can influence the thermostability of ISVPs, although this is not surprising, given that most of the length of μ1N is buried inside the folded μ1 trimer structure (22). The other mutations discussed in this report—K459E, Y431C, T325A, and E89K—are all within the δ-fragment region of μ1.

The variety of second-site mutations, most at some distance from residue 371 in the μ1 trimer structure (Fig. 7C through E), suggests that intragenic pseudoreversion of a thermostabilizing mutation can occur by a general mechanism of thermolabilization, not requiring a compensatory mutation that specifically counteracts the initial mutation. This is supported by the finding that the thermolabilizing mutation S134L reverts the heat resistance phenotype of the orthologous thermostabilizing mutation K459E (Fig. 3C) as well as that of D371A. Furthermore, the presence of the thermolabilizing mutation T325A in the double mutant ID46-2 (Y431C+T325A) strongly suggests that Y431C/T325A is another thermostabilizing/thermolabilizing pair (Fig. 3D). If so, that would indicate that pseudoreversion is not limited to D371A but could occur in the context of a variety of different thermostabilizing mutations. On the other hand, the effect of second-site mutation Q372E in the double mutant IL54-5-1 (D371A+Q372E) may be specific to the thermostabilizing mutation D371A, as it is adjacent in the primary sequence and returns an acidic residue that could potentially restore the salt bridge with K459 (22). Experiments with different mutant forms of μ1 in purified trimers (38) will be needed to prove whether the effects of the different thermostabilizing and thermolabilizing mutations are inherent to each μ1 trimer or at least partly dependent on contacts within the networked lattice of the μ1 outer capsid (see below).

Pseudoreversion of entry defects has been reported for other viruses. For example, an E-protein mutant of yellow fever virus, with impaired cell entry and spread, yielded second-site reversion mutations, also in the E protein, which were hypothesized to affect its hinge-like conformational change during membrane fusion (37). Similarly, a fusion block mutation in the Semliki Forest virus E1 fusion protein also yielded second-site reversion mutations, located within the hinge region, the membrane-interacting tip, and the predicted stem groove (11). Some of the reversion mutations were the same as ones selected previously for cholesterol-independent fusion activity (14, 34).

In the reovirus outer capsid, μ1 trimers contact neighboring trimers across local quasi-twofold axes (16, 22, 39) (Fig. 7B). These contacts are concentrated in two distinct regions, one near the top of each trimer and one near the base (39) (Fig. 7C). The thermostabilizing mutations D371A and K459E are located near the upper trimer-trimer contact region, and with one exception (see next paragraph), the second-site mutations from IL54-5 are located near either the upper or lower contact region: T332I, Q372E, and N533D near the upper and S132L, S134L, A184V, and P277L/T near the lower (Fig. 7C through E). Residue 87, at which another second-site mutation (P87Q) is located, is not visible in the μ1-σ3 crystal structure (22), but in a high-resolution electron-cryomicroscopy reconstruction of the virion, the loop containing this residue is seen to project across the quasi-twofold axis near the base of the μ1 trimer and to make contacts with the neighboring trimer (39). In sum, these findings suggest that the reovirus outer capsid can be either thermostabilized or thermolabilized by mutations that affect the trimer-trimer contacts across these local twofold axes.

The two mutations in ID46-2, including the thermolabilizing mutation T325A, are located near the top of the μ1 trimer at intersubunit contacts within the trimer. This not surprisingly suggests that the reovirus outer capsid can also be either thermostabilized or thermolabilized by mutations that affect the intersubunit contacts within trimers. Interestingly, however, in ID46-4, the other double mutant with the putatively thermostabilizing mutation Y431C, the second-site mutation is E89K, which is again found in the loop that projects across the quasi-twofold axis near the base of the μ1 trimer and makes contacts with the neighboring trimer. Thus, in this case, it appears that a putatively thermolabilizing mutation (E89K) that affects trimer-trimer contacts can counteract a putatively thermostabilizing mutation (Y431C) that affects intersubunit contacts within trimers. Similarly, the second-site mutation in IL54-5-14, M40I, which is mentioned as an exception in the preceding paragraph, is found near the base of the μ1 trimer and makes intersubunit contacts within trimers. Thus, in this case, it appears that a putatively thermolabilizing mutation (M40I) that affects intersubunit contacts within trimers can counteract a thermostabilizing mutation (D371A) that affects trimer-trimer contacts. In conclusion, it seems likely that intersubunit contacts both within and between trimers work in concert to regulate reovirus outer-capsid stability and that changes in one can compensate for changes in the other.

It has been proposed that μ1 rearrangement begins with unwinding at the top of the trimer and that stabilizing mutations prevent unwinding by locking the tops of the trimers (22, 24, 38). However, the thermolabilizing mutations S134L and P277T, at the base of the trimer, were found to revert thermostability conferred by D371A, which is at the top of the trimer. Similarly, the putatively thermolabilizing mutation E89K, at the base of the trimer, may revert the putatively thermostabilizing mutation Y431C, at the top of the trimer. These examples suggest that μ1 rearrangement is regulated in concert by contacts over nearly the full radial span of the trimer and that the top-down order of the rearrangement might not be strictly required.

In the virus particle, 200 μ1 trimers are arranged with quasi- T=13 (laevo) symmetry, substituted around the 12 icosahedral fivefold axes with pentameric λ2 turrets (16). As a result, there are five different types of quasi-twofold axes at which μ1 trimers contact each other, and a related interface at which a μ1 trimer contacts λ2. Of the 200 μ1 trimers, 60 participate in this μ1-λ2 interaction on one side. These contacts involve residues at the base of the μ1 trimer, in a region overlapping that of the related trimer-trimer contacts (39). Thus, the second-site mutations near the twofold axes at the base of the μ1 trimer (P87Q, E89K, S132L, S134L, A184V, and P277L/T) may affect trimer-λ2 contacts as well as trimer-trimer contacts, which may also contribute to labilizing the outer capsid.

The results in this report reveal the special utility of “double” HR mutants for identifying thermolabilizing mutations as well as for identifying thermostabilizing mutations that impart a large infectivity defect. Infectivity defects attributable to the previously characterized “single” HR mutants were small at most (24). The described strategy of exploring the genetic diversity of the initial plaque after heat selection, prior to further plaque purifications, is also useful.

Although the μ1 mutations D371A and K459E thermostabilize pRCs to similar extents (Fig. 3), intragenic pseudoreversion was not observed with the K459E-containing mutant, IL62-3 (24). One possible explanation is that D371A confers slightly greater stability, placing virus particles just over a threshold at which stabilization begins to translate to an infectivity disadvantage. Interestingly, even though a defect was not consistently detected in single-cycle growth curves, IL62-3 formed smaller plaques than WT T1L (24), suggesting that K459E may place virus particles close to this threshold as well. Alternatively, there may be a specific effect of the D371A mutation that leads to a greater impairment on infectivity or growth than does K459E. For example, although not revealed by in vitro recoating, D371A might also impart an assembly defect that impairs growth. It is also possible that the IL62-3 mutant has a growth-enhancing pseudoreversion in another gene. Further experiments are needed to distinguish among these and other possibilities.

Studies of enzymes from organisms adapted to different temperatures indicate that efficient catalysis depends on an appropriate balance between thermostability and flexibility (17). Similarly, proper deployment of the reovirus membrane penetration machinery likely depends on tuning outer-capsid stability within a relatively narrow window. The ISVP outer capsid must be stable enough to avoid denaturation or premature ISVP* conversion yet remain susceptible to conversion when appropriate for cell entry. The specific factors that promote ISVP* conversion in cells are not well understood. However, the results of this study, as well as previous work with an engineered hyperstable mutant (8), suggest that the capacity of reovirus to capitalize on the thermal energy of its surroundings is important and therefore subject to selective pressure. Having a large collection of both thermostabilizing and thermolabilizing mutations in μ1 should aid in ongoing studies of its conformational rearrangements during cell entry as well as its roles in reovirus outer-capsid stability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tijana Ivanovic, John Parker, and Lan Zhang for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants F31 AI064142 to M.A.A., R21 AI071197 to J.Y., and R01 AI46440 to M.L.N. and also by NSF grant EIA-0331337 to J.Y. J.K.M. received support from National Library of Medicine grant 5T15LM007359 as well as from NIH grant T32 GM08349 to the Biotechnology program at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. M.A.A. received additional support from NIH grant T32 GM07226 to the Biological and Biomedical Sciences program at Harvard University, Division of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agosto, M. A., T. Ivanovic, and M. L. Nibert. 2006. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:16496-16501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baer, G. S., and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Mutations in reovirus outer-capsid protein σ3 selected during persistent infections of L cells confer resistance to protease inhibitor E64. J. Virol. 71:4921-4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodkin, D., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1989. Proteolytic digestion of reovirus in the intestinal lumens of neonatal mice. J. Virol. 63:4676-4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borsa, J., D. G. Long, T. P. Copps, M. D. Sargent, and J. D. Chapman. 1974. Reovirus transcriptase activation in vitro: further studies on the facilitation phenomenon. Intervirology 3:15-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broering, T. J., A. M. McCutcheon, V. E. Centonze, and M. L. Nibert. 2000. Reovirus nonstructural protein μNS binds to core particles but does not inhibit their transcription and capping activities. J. Virol. 74:5516-5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandran, K., and M. L. Nibert. 1998. Protease cleavage of reovirus capsid protein μ1/μ1C is blocked by alkyl sulfate detergents, yielding a new type of infectious subvirion particle. J. Virol. 72:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandran, K., D. L. Farsetta, and M. L. Nibert. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol. 76:9920-9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandran, K., J. S. L. Parker, M. Ehrlich, T. Kirchhausen, and M. L. Nibert. 2003. The δ region of outer-capsid protein μ1 undergoes conformational change and release from reovirus particles during cell entry. J. Virol. 77:13361-13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandran, K., S. B. Walker, Y. Chen, C. M. Contreras, L. A. Schiff, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 1999. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and σ3. J. Virol. 73:3941-3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandran, K., X. Zhang, N. H. Olson, S. B. Walker, J. D. Chappell, T. S. Dermody, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 2001. Complete in vitro assembly of the reovirus outer capsid produces highly infectious particles suitable for genetic studies of the receptor-binding protein. J. Virol. 75:5335-5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chanel-Vos, C., and M. Kielian. 2006. Second-site revertants of a Semliki Forest virus fusion-block mutation reveal the dynamics of a class II membrane fusion protein. J. Virol. 80:6115-6122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, C. T., and H. J. Zweerink. 1971. Fate of parental reovirus in infected cell. Virology 46:544-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chappell, J. D., A. E. Prota, T. S. Dermody, and T. Stehle. 2002. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 reveals evolutionary relationship to adenovirus fiber. EMBO J. 21:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee, P. K., C. H. Eng, and M. Kielian. 2002. Novel mutations that control the sphingolipid and cholesterol dependence of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein. J. Virol. 76:12712-12722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coombs, K. M. 1998. Stoichiometry of reovirus structural proteins in virus, ISVP, and core particles. Virology 243:218-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dryden, K. A., G. Wang, M. Yeager, M. L. Nibert, K. M. Coombs, D. B. Furlong, B. N. Fields, and T. S. Baker. 1993. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 122:1023-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields, P. A. 2001. Review: protein function at thermal extremes: balancing stability and flexibility. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 129:417-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furlong, D. B., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1988. σ1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 62:246-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golden, J. W., J. A. Bahe, W. T. Lucas, M. L. Nibert, and L. A. Schiff. 2004. Cathepsin S supports acid-independent infection by some reoviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 279:8547-8557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper, J. W., and B. N. Fields. 1996. Role of the μ1 protein in reovirus stability and capacity to cause chromium release from host cells. J. Virol. 70:459-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kothandaraman, S., M. C. Hebert, R. T. Raines, and M. L. Nibert. 1998. No role for pepstatin-A-sensitive acidic proteinases in reovirus infections of L or MDCK cells. Virology 251:264-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liemann, S., K. Chandran, T. S. Baker, M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2002. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, μ1, in a complex with its protector protein, σ3. Cell 108:283-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luria, S. E., and M. Delbrück. 1943. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28:491-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middleton, J. K., M. A. Agosto, T. F. Severson, J. Yin, and M. L. Nibert. 2007. Heat-resistance mutations in outer-capsid protein μ1 selected by heat inactivation of infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reovirus. Virology 361:412-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middleton, J. K., T. F. Severson, K. Chandran, A. L. Gillian, J. Yin, and M. L. Nibert. 2002. Thermostability of reovirus disassembly intermediates (ISVPs) correlates with genetic, biochemical, and thermodynamic properties of major surface protein μ1. J. Virol. 76:1051-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nibert, M. L. 1993. Structure and function of reovirus outer capsid proteins as they relate to early steps in infection. Ph.D. thesis. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- 27.Nibert, M. L. 1998. Structure of mammalian orthoreovirus particles. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 233:1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nibert, M. L., and B. N. Fields. 1992. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein μ1/μ1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J. Virol. 66:6408-6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nibert, M. L., A. L. Odegard, M. A. Agosto, K. Chandran, and L. A. Schiff. 2005. Putative autocleavage of reovirus μ1 protein in concert with outer-capsid disassembly and activation for membrane permeabilization. J. Mol. Biol. 345:461-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odegard, A. L., K. Chandran, X. Zhang, J. S. L. Parker, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 2004. Putative autocleavage of outer capsid protein μ1, allowing release of myristoylated peptide μ1N during particle uncoating, is critical for cell entry by reovirus. J. Virol. 78:8732-8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverstein, S. C., M. Schonberg, D. H. Levin, and G. Acs. 1970. The reovirus replicative cycle: conservation of parental RNA and protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 67:275-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spencer, S. M., J.-Y. Sgro, K. A. Dryden, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 1997. IRIS Explorer software for radial depth cueing reovirus particles and other macromolecular structures determined by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Struct. Biol. 120:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturzenbecker, L. J., M. L. Nibert, D. B. Furlong, and B. N. Fields. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 61:2351-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vashishtha, M., T. Phalen, M. T. Marquardt, J. S. Ryu, A. C. Ng, and M. Kielian. 1998. A single point mutation controls the cholesterol dependence of Semliki Forest virus entry and exit. J. Cell Biol. 140:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virgin, H. W., IV, M. A. Mann, B. N. Fields, and K. L. Tyler. 1991. Monoclonal antibodies to reovirus reveal structure/function relationships between capsid proteins and genetics of susceptibility to antibody action. J. Virol. 65:6772-6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virgin, H. W., IV, R. Bassel-Duby, and K. L. Tyler. 1988. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing). J. Virol. 62:4594-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlaycheva, L., M. Nickells, D. A. Droll, and T. J. Chambers. 2004. Yellow fever 17D virus: pseudo-revertant suppression of defective virus penetration and spread by mutations in domains II and III of the E protein. Virology 327:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, L., K. Chandran, M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2006. The reovirus μ1 structural rearrangement that mediates membrane penetration. J. Virol. 80:12367-12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, X., Y. Ji, L. Zhang, S. C. Harrison, D. C. Marinescu, M. L. Nibert, and T. S. Baker. 2005. Features of reovirus outer capsid protein μ1 revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of the virion at 7.0 Å resolution. Structure 13:1545-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]