Abstract

Increasing HIV knowledge is a focus of many HIV education and prevention efforts. While the bivariate relationship of HIV serostatus disclosure with HIV-related knowledge and stigma has been reported in the literature, little is known about the mediation effect of stigma on the relationship of HIV knowledge with HIV serostatus disclosure. Data from 4,208 rural-to-urban migrants in China were analyzed to explore this issue. Overall, 70% of respondents reported willingness to disclose their HIV status if they were HIV-positive. Willingness to disclose was negatively associated with misconceptions about HIV transmission and stigma. Stigma mediated the relationship between misconceptions and willingness to disclose among women but not men. The mediation effect of stigma suggests that stigmatization reduction would be an important component of HIV prevention approaches. Gender inequality needs to be addressed in stigmatization reduction efforts.

Introduction

HIV serostatus disclosure provides potential benefits to infected persons, their partners and communities (De Rosa & Marks, 1998; Pealer & Peterman, 2003). However, the rates of serostatus disclosure are not optimistic. In developing countries, rates of sharing HIV testing results with sexual partner among women ranged widely from 16.7% to 86% depending on time frame for disclosure and population of interest (Medley et al., 2004). In developed countries, low rates of self-disclosure have also been reported. For example, a study in Los Angeles reported that only 5.5% (51/926) of sexual partners during the last 12 months were informed of their risk by their HIV-infected partners (Marks et al., 1992). Studies addressing factors associated with disclosure or non-disclosure are relevant for developing effective prevention and public health policy.

Factors associated with HIV serostatus (non)disclosure have been explored, with corresponding explanatory theories proposed, since the early 1990s. Before the availability of HIV antiretroviral treatment, a commonly used theory in studying HIV-status disclosure was the disease progression theory, proposing that people disclose out of necessity as their HIV infection progressed to AIDS (Kalichman, 1995). Mixed results have been reported regarding the relationship between disease progression and HIV-status disclosure (Hays et al., 1993; Mansergh et al., 1995; O’Brien, 2003; Perry et al., 1994; Serovich, 2001; Stein et al., 1998). More recently, competing consequence theory has begun to emerge (Serovich, 2001). This theory proposed that persons with HIV were likely to reveal to significant others and sexual partners once the rewards for disclosing outweighed the associated costs. Several studies have shown empirical support for this theory (Derlega et al., 1998; Marks et al., 1992).

This theory has implications for understanding cultural influences on disclosure (Rubin et al., 2000). In a social context where HIV/AIDS remains mysterious and HIV-related stigma prevails, decisions regarding disclosure may be influenced by concerns over possible negative consequences. Omarzu (2000) argued that disclosure often involved risk, particularly when the information revealed was potentially embarrassing, negative or emotionally intense. According to Omarzu, a decision to disclose HIV status involves a cognitive appraisal of negative consequences that is based on an individual’s knowledge of HIV, attitudes toward HIV/AIDS or HIV-related behavior and perceived social attitudes towards people with HIV. Therefore, a decision regarding disclosure may be influenced by HIV-related knowledge and stigma.

Increasing HIV knowledge has been a primary focus of many HIV education and prevention efforts since HIV emerged, particularly in countries at an early stage of the epidemic such as China. However, little is known about the relationship between HIV knowledge and the decision to disclose and whether stigma mediates the effect of HIV knowledge on this decision. Therefore, in the current study, we propose and test a conceptual framework about the relationship among these factors.

Conceptual framework

The relationship between HIV-related knowledge and disclosure has been poorly documented in the literature. However, several intervention practices have suggested a positive relationship. Information-based approaches combined with counseling have been observed to increase disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS in countries such as Uganda (Kaleeba et al., 1997) and Zimbabwe (Kerry & Margie, 1996).

The negative relationship between stigma and disclosure has been well documented in the literature. Stigma refers to attitudes or perceptions of shame, disgrace, blame or dishonor associated with the disease (Cock et al., 2002). Manifestations of stigma have been documented as withholding of medical treatment, rejection by families and community, denial of jobs and housing, loss of the right to education and so on (Lichtenstein, 2003). Fear of being stigmatized may prevent HIV-infected persons from disclosing their HIV status (Chesney & Smith, 1999). Studies among women in developing countries found that barriers to disclosure included fear of accusations of infidelity, abandonment, discrimination and violence (Medley et al., 2004). A study among 93 HIV-infected persons in San Francisco found that barriers to disclosure included concerns about health insurance (71%) and concerns about stigmatization (61%) (Stempel et al., 1995).

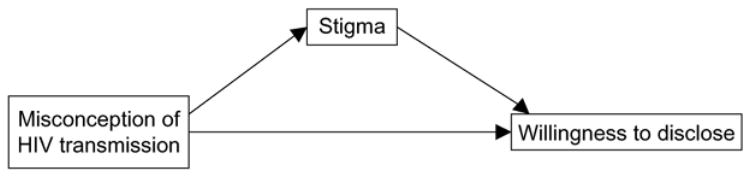

HIV/AIDS-related stigma comes from a powerful combination of fear and shame (Piot, 2001). Mr. Zahir Uddin Swapon, Secretary General of the Parliamentary Group on HIV/AIDS said, ‘People stigmatize due to fear stemming from ignorance’ (UNAIDS, 2004). Lack of understanding of the disease, misconceptions about how HIV is transmitted and lack of knowledge of protection may trigger stigmatization (Aggleton et al., 2002). The conceptual framework of the mediation effect of stigma is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of mediation effect of stigma on the effects of HIV knowledge on willingness to disclose.

It is estimated that currently there are 840,000 people infected with HIV in China, although only 89,067 infections have been officially reported (State Council AIDS Working Committee Office, 2004). Nearly 95% of infected persons do not know their HIV-infected status. As in many countries, voluntary counseling and testing is being piloted in China and may be expanded to the whole nation in the near future. How willing HIV-infected persons are to share their HIV status and how misconceptions about HIV transmission may influence willingness to disclose are questions needing immediate answers. However, few studies in China have addressed the issue of disclosure (Liu et al., 2002; Rubin, 2000). Therefore, in the current study, we proposed this mediation effect among Chinese rural-to-urban migrants, a population vulnerable to HIV/STD infection (Li et al., 2004). We aimed: (1) to explore willingness to disclose HIV status if they were HIV-positive and its association with HIV-related misconception and stigma; and (2) to examine whether stigma mediates the effect of misconception on willingness to disclose. We anticipated that misconception might be negatively associated with willingness to disclose and the relationship might be mediated by stigma.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 4,208 rural-to-urban migrants recruited in a feasibility study of HIV/STD prevention intervention in two metropolitan areas, Beijing and Nanjing, China. Participants had a rural residence, worked in the city without having a permanent city residence and were between 18 and 30 years of age. The sample included 40% women and 60% men. Their mean age was 24.5 years (SD = 3.8). The majority of participants (97%) were of Han ethnicity (i.e. the majority ethnicity in China), single (72%) and had finished at least six years of formal education (94%). Nearly 96% of the participants were currently employed. The participants had an average of 4.3 years’ experience of migration, with 58% having migrated to at least two cities prior to our study. More descriptive information about the participants is available in previous reports (Li et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004).

Sampling

Occupational clusters were utilized for sampling since there is no reliable local census data of the migrant population for random sampling (Zhang, 2000). Ten occupational clusters covering more than 90% of the migrants, plus job markets where currently unemployed migrants present, served as the sampling frame. The ten occupational clusters included restaurants, hotels, barbershops/beauty salons, bathhouses/massage parlors, nightclubs/karaoke/dancehalls/bars, small retail shops, domestic services, street vendors, construction and factory workers. Quota-sampling of these occupational groups was utilized so that the number of participants would be proportional to the estimated number of migrants in each occupational cluster. To prevent over-sampling from any single workplace (e.g. store, club, office, construction site, workshop in factory), the number of respondents recruited from any workplace did not exceed 10% of total migrants in the workplace or ten individuals, whichever was greater.

Procedure

Before starting the survey, employers or workplace managers were contacted for permission to conduct the survey at their premises. Trained outreach staff went to these workplaces to recruit eligible migrants. After providing informed consent individually, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire in a separate room or a private space at their workplace or a nearby location convenient to participants. The questionnaire, which was pilot-tested and revised before the survey, took approximately 40–60 minutes to complete. Assistance (e.g. reading questions to them) was provided to a few respondents with limited literacy. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at Wayne State University, Beijing Normal University and Nanjing University.

Measurements

In the current study, the primary outcome of interest was willingness to disclose HIV status if infected, measured by one item with multiple responses: ‘Would you be willing to disclose your HIV status to others if you were HIV-positive?’ Participants who reported they would disclose their status to no one were coded as 0 and those who would like to disclose to someone (e.g. family member, relative, friend or others) were coded as 1.

Independent variables examined included misconception about HIV transmission and stigma. Misconception about HIV transmission was created by adding correct responses to six questions regarding transmission of HIV through daily contact (Table I). The score ranged from 0–6, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of misconception. The internal consistency for the scale was 0.78 for females and 0.77 for males.

Table I.

Questions for measurements.

| Measurements | Questions |

|---|---|

| Willingness to disclose | Would you be willing to disclose your HIV status to others if you were HIV-positive? |

| Misconception of HIV transmission |

|

| Stigma |

|

HIV-related stigma was assessed through four statements about attitudes towards people with HIV (Table I). Participants were asked to respond to each statement by indicating their level of agreement on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree and 4 = strongly agree). A composite score, ranging from 1–4, was created by averaging responses (with necessary reverse coding) to these four statements. Higher scores reflected higher levels of stigma. The internal consistency for this score was 0.62 for females and 0.60 for males.

Data analysis

General

Since stigma and willingness to disclose may be gender related, data were analyzed for males and females separately (Warszawshi & Meyer, 2002). Frequency distributions of misconception and stigma were examined and percentages of willingness to disclose if infected for each category were calculated. The association of these variables with willingness to disclose was further evaluated through binary logistic regression, treating misconception and stigma as continuous variables. The odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.

Testing of mediation effect

A mediation effect was tested following the methodology developed by Baron and Kenny (1986). According to Baron and Kenny, three regression models and four conditions are necessary for assessing mediation effect: (1) the predictor must be significantly associated with the mediator in the regression of the mediator on the predictor, (2) the predictor must be significantly associated with the dependent variable in the regression of the dependent variable on the predictor, (3) the mediator must be significantly associated with the dependent variable in the regression of the dependent variable on both the predictor and the mediator and (4) the effect of the predictor on the dependent variable must be reduced in magnitude after conditioning the mediator.

To test the mediation effect of stigma on the association of misconception with willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection, we first regressed stigma on misconception, followed by a second regression of willingness to disclose on misconception. Finally, we regressed willingness to disclose on both misconception and stigma. For each regression, age and marital status were controlled for females; age, education attainment and marital status were controlled for males.

Regression coefficients for each equation were estimated using maximum likelihood (for the binary logistic regression) or least square methods (for the linear regression). The coefficient for the effect of the predictor (i.e. misconception) on the mediator (i.e. stigma) was denoted as α. The coefficient for the effect of the predictor on the dependent variable (i.e. willingness to disclose HIV status if infected) was denoted as τ. The effect of the predictor on the dependent variable conditioning the mediator was denoted as τ′ and the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable with the predictor in the model was denoted as β.

Results

Among 4,208 migrants recruited, 4,111 participants (97.7%) responded to the question of willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection. Among them, 2901 (70.6%) reported that if they were HIV-positive they would be willing to share their HIV status with someone. The proportion of willingness to disclose was 68.6% (or 1144/1668) among female participants and 71.9% (or 1757/2443) among male participants (see Table II).

Table II.

Number and percentage of willingness to disclose, by gender.

| Female

|

Male

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Notify (%) | N | Notify (%) | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–20yrs | 492 | 69.3 | 568 | 73.2 |

| 21–25yrs | 808 | 66.5 | 1,016 | 70 |

| 26–30yrs | 366 | 72.7 | 857 | 73.2 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.022(0.99231.052) | 1.008(0.98631.032) | ||

| Education | ||||

| ≤6 grades | 128 | 60.9 | 113 | 63.7 |

| 7– ≤9 grades | 835 | 69.5 | 1,430 | 73.8 |

| >9 grades | 689 | 69.5 | 884 | 70 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.110(0.96031.284) | 0.939(0.82131.075) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 1,258 | 67.1 | 1,617 | 70.3 |

| Married | 368 | 75.5 | 753 | 75.3 |

| OR (95% CI) never married: married | 0.660(0.50630.861) | 0.777(0.63830.946) | ||

| Misconception of transmission | ||||

| 0 | 116 | 69 | 174 | 74.7 |

| 1–3 | 772 | 71.5 | 1,049 | 73.1 |

| 4–6 | 778 | 65.8 | 1,216 | 70.4 |

| OR (95% CI) | 0.917 (0.86630.971) | 0.963 (0.91731.010) | ||

| HIV-related stigma | ||||

| 1 | 65 | 86.2 | 95 | 80 |

| 2 | 1,045 | 72.8 | 1,400 | 74.6 |

| 3 | 525 | 59.2 | 880 | 67.8 |

| 4 | 33 | 51.5 | 65 | 53.8 |

| OR (95% CI) | 0.454 (0.36830.560) | 0.598 (0.50730.706) | ||

Without specification, OR refers to odds ratio of willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection with one unit increase of independent variable.

There were no significant differences in terms of willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection across age and educational groups. Compared to ever married participants, never married participants tended to be less likely to disclose their HIV status to someone if infected (OR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.51–0.86 for women and OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.64–0.95 for men). The percent of willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection was approximately 75% in both ever married women and men, but it reduced to 67.1% for never married women and 70.3% for never married men.

As shown in Table II, significant negative associations of willingness to disclose if infected with misconception and stigma were observed in women. With one unit increase of misconception, the odds of willingness to disclose decreased 8.3% (95%CI: 2.9–13.4%). Likewise, with one unit increase in stigma, the odds of willingness to disclose decreased 54.6% (44–63.2%).

The contingency frequency distribution also showed a general trend in percentages of willingness to disclose in the event of infection. Approximately 73–86% of women perceiving no stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV-infected persons would be willing to disclose their HIV status if they were HIV-positive. While this percentage decreased to 59% among women who perceived stigmatizing attitudes and down further to 52% among women who perceived strongly stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV-infected persons.

Similar associations of misconception and stigma with willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection were observed among men, except that the negative relation between misconception and disclosure was not statistically significant (Table II). With one unit increase in stigma, the odds of willingness to disclose if infected decreased 40.2% (95% CI: 29.4–49.3%).

Mediation effect

For female participants, misconception was positively associated with stigma (α = 0.0450, p < 0.001) and negatively associated with willingness to disclose (τ = −0.0830, p < 0.01). When stigma was introduced in the model, the association between misconception and willingness to disclose was not statistically significant any more (τ′ = −0.0508, p > 0.05) but the effect of stigma on willingness to disclose remained significant (β = −0.7640, p< 0.001) (Table III). Stigma therefore served as a mediator in the path of misconception to willingness to disclose in female participants.

Table III.

Coefficients and their significant status in regression models establishing mediation for women and men, with controlling demographic characteristics.

| Stigma (X→M) (<α>) | Disclosure (X→Y) (<τ>) | Disclosure ({X, M}→Y) (<τ′>) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | |||

| Misconception of transmission (X) | 0.0450 ** (0.0068) | −0.0830 * (0.0300) | −0.0508 (0.0306) |

| Stigma (M, <β>) | −0.7640 ** (0.1117) | ||

| Male | |||

| Misconception of transmission (X) | 0.0401 ** (0.0058) | −0.0383 (0.0252) | −0.0168 (0.0255) |

| Stigma (M, <β>) | −0.5493 ** (0.0885) | ||

Figures in the table were coefficients and standard errors of coefficients which were in parenthesis;

M: refers to mediator, HIV-related stigma

Y: refers to outcome, willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

For male participants misconception was not found to be significantly associated with willingness to disclose (τ = −0.0382, p > 0.05). Therefore, according to the criteria for mediation suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), it would be inappropriate to assess the mediation effect of stigma on the relationship between misconception and willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection.

Discussion

Stigma appeared to mediate the relationship between misconception and willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection in women but not men. For both men and women, misconception was significantly positively associated with stigma, stigma was negatively associated with willingness to disclose and misconception was negatively associated with willingness to disclose.

The mediation effects of stigma have important implications for HIV-serostatus disclosure and other HIV prevention activities, including voluntary counseling and testing, returning for results and entering care. All these activities focus on increasing individuals’ HIV knowledge and awareness of the risk of being infected or spreading HIV, while paying little attention to addressing the fear of being stigmatized if they are HIV-positive. Individuals who internally stigmatize people with HIV typically are more likely to perceive being stigmatized by others if they were HIV-positive. Due to the negative attitudes toward people with HIV and the fear of being treated the same way from revealing the positive serostatus, people may, despite their knowledge, still refuse to participate in any of these activities and may be reluctant to change their behaviors, such as not using condoms. The negative association of stigma with willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection observed in the current study supports the findings that stigma prevents HIV/STD-infected persons from publicizing their infection status (Fortenberry et al., 2002; Hook et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2002). Reduction of stigmatizing belief should be considered as an important component of successful HIV prevention approaches.

Among recent studies related to correlates of disclosure conducted in developed countries, few have examined the relationship between HIV knowledge and disclosure. In these countries, people generally have good knowledge of HIV infection and transmission. However, in developing countries, especially those countries where HIV is in a relatively early stage and the dissemination system for health information does not function well, misconception about HIV transmission is common. Our study indicates that only 7.1% (290/4205) of participants believed that daily contact would not transmit HIV. This finding suggests that in countries such as China, where HIV still remains mysterious to many people, study of disclosure factors needs to consider promoting HIV knowledge and correcting public misconception about HIV infection and transmission.

Compared to their male counterparts, female participants were less likely to share their HIV status if they were infected when they possessed severe misconception about HIV transmission or possessed stigmatizing attitudes toward people with HIV. This finding was not consistent with a previous French study, which observed significantly higher percentages of disclosure to main/current sexual partners among both women and adolescent girls than men and adolescent boys (Warszawshi & Meyer, 2002). One possible reason for the discrepancy may be gender inequality in the context of stigmatization in Chinese culture. In traditional Chinese culture, women are more vulnerable to negative consequences (e.g. blame, physical violence, emotional torture) from both family and society if they are found to be HIV-positive (Tang et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2005). Fear of these negative consequences may prevent women from sharing their HIV infection status. Gender inequality has long accompanied human society, especially in developing countries (Kaye, 2004; Riley, 1997; Sachar, 1990; Von Massow, 2000). Women were believed to be at a relative disadvantage to men on a variety of matters such as education, employment, income and sexual relationships. In the context of the HIV epidemic, gender inequality has been recognized as the driving force behind the epidemic (Kaye, 2004) and it serves as a serious barrier to HIV-related stigmatization reduction. Enhancing women’s social and economic status must be integrated into HIV prevention strategies.

The negative association for women between misconceptions and willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection may be explained by fear of being isolated. Women with higher levels of misconception tend to believe that HIV can be transmitted easily through daily contact and believe that disclosure may frighten people around them, resulting in them being isolated or even ostracized. In contrast, the association between misconception and willingness to disclose did not appear to exist for Chinese men in the current study. We further explored the data and found that the negative association between misconception and willingness to disclose HIV status in the event of infection holds for women only when the person disclosed to is a family member. We therefore speculate that a sense of superiority in men in family life may throw a light on the explanation. In the traditional Chinese family, men have supreme authority. Other family members need to submit to them. Men’s sense of superiority in family life makes them less frightened to disclose their HIV status in the event of infection, even if they perceive high misconceptions.

There are several potential limitations in the current study. First, our sample was a convenience sample rather than a random sample. Although great efforts were made to ensure the representativeness of the sample, the findings may not be generalized to other migrant populations in China. Second, the primary outcome of interest is measured in a hypothetical situation rather than actual practice of disclosure among HIV-infected people. The impact of assumed HIV infection may be quite different from the impact of a real HIV infection notification. Third, HIV-related knowledge was assessed by misconception about HIV transmission, which reflected only one aspect of HIV knowledge. Forth, the assessment of participants’ own personal stigmatizing attitudes was included in the measurement of HIV stigma. While the personal attitudes might be important, they are different from perceived stigma in general (e.g. perceived social attitudes towards HIV/AIDS infected individuals) and the latter might be more relevant in studying the issue of disclosure. Finally, since the original study was not designed to explore correlates of disclosure, some valuable information, such as perceived consequences of disclosure, was not collected.

Recommendations

The mediation effect of stigma suggests that increasing HIV knowledge is not sufficient for effective HIV prevention and control. HIV-related stigmatization reduction must be included as an important component of HIV prevention approaches. Education efforts to mitigate the effect of stigma need to be delivered. Multiple channels, including various forms of mass media, should be well used to disseminate HIV-related knowledge, information, laws or regulations to correct distorted actions toward people living with HIV/AIDS. Gender inequality needs to be addressed in stigmatization reduction. Further studies on social culture reason for stigma are needed.

Acknowledgments

The study is funded by NIMH/NIH (grant number R01MH64878). The authors would like to thank our participating investigators at Beijing Normal University Institute of Developmental Psychology, Nanjing University Institute of Mental Health and West Virginia University School of Medicine for their contributions to questionnaire development and data collection. Special thanks to Dr. Ambika Mathur for her assistance in editing the manuscript.

References

- Aggleton P, Parker R UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) World AIDS Campaign 2002–2003: A conceptual framework and basis for action: HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination. 2002 Available at: http://www.eldis.org/static/DOC10145.htm.

- Baron R, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care–the potential role of stigma. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42:1158–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Cock KMD, Mbori-Ngacha D, Marum E. Shadow on the continent: Public health and HIV/AIDS in Africa in the 21st century. The Lancet. 2002;360:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa CJ, Marks G. Preventive counseling of HIV-positive men and self-disclosure of serostatus to sex partners: New opportunities for prevention. Health Psychology. 1998;17:224–231. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Lovejoy D, Winstead BA. Personal accounts of disclosing and concealing HIV-positive test results: Weighing the benefits and risks. In: Derlega V, Barbee A, editors. HIV infection and social interaction. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Mcfarlane M, Bleakley A, Bull S, Fishbein M, et al. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and human immunodeficiency virus screening. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:378–381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RB, Mckusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, Coates TJ. Disclosing HIV seropositivity to significant others. AIDS. 1993;7:425–431. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook EW, Richey CM, Leone P, Balan G, Spalding C, et al. Delayed presentation to clinics for sexually transmitted diseases by symptomatic patients: A potential contributor to continuing STD morbidity. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1997;24:443–448. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaleeba N, Kalibala S, Kaseje M, Ssebbanja P, Anderson S, et al. Participatory evaluation of counseling, medical and social services on the AIDS support organization (TASO) AIDS Care. 1997;9:13–26. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Understanding AIDS: A guide for mental health professionals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye DK. Gender inequality and domestic violence: Implications for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention. African Health Sciences. 2004;4:67–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerry K, Margie C. Cost-effective AIDS awareness program on commercial farms in Zimbabwe. Paper presented at the international conference on HIV/AIDS; Vancouver. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Fang X, Lin D, Mao R, Wang J, et al. HIV/STD risk behaviors and perceptions among rural-to-urban migrants in China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:538–56. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.6.538.53787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B. Stigma as a barrier to treatment of sexually transmitted infection in the American deep south: Issues of race, gender and poverty. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:2435–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Detels R, Li X, Ma E, Yin Y. Stigma, delayed treatment and spousal notification among male patients with sexually transmitted disease in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:335–343. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Richardson JL, Ruiz MS, Maldonado N. HIV-infected men’s practices in notifying past sexual partners of infection risk. Public Health Reports. 1992;107:100–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Marks G, Simoni JM. Self-disclosure of HIV infection among men who vary in time since seropositive diagnosis and symptomatic status. AIDS. 1995;9:639–644. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199506000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, Mcgill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: Implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation. 2004;82:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien ME, Richardson-Alston G, Ayoub M, Magnus M, Peterman TA, Kissinger P. Prevalence and correlates of HIV serostatus disclosure. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30:731–735. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000079049.73800.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omarzu J. A disclosure decision model: Determining how and when individuals will self-disclose. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2000;4:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pealer LN, Peterman TA. When it comes to contact notification, HIV is not TB. The International Journal of Tubercoulosis and Lung Disease: the official journal of the International Union against tuberculosis and lung disease. 2003;7:S337–S341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SW, Card CA, Moffatt M, Jr, Ashman T, Fishman B, Jacobsberg LB. Self-disclosure of HIV infection to sexual partners after repeated counseling. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P. World conference against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Durban South Africa. 2001 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/whatsnew/speeches/eng/piot040901racism.htm.

- Riley NE. Gender, power and population change. Population Bulletin. 1997;52:1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DL, Yang H, Porte M. A comparison of self-reported disclosure among Chinese and North Americans. In: Pertronio S, editor. Balancing the secrets of private disclosures. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sachar RK, Sehgal R, Verma J, Prakash V, Singh WP. The female child: A picture of denials and deprivations. Indian Journal of Maternal Child Health. 1990;1:124–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serovich JM. A test of two HIV disclosure theories. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13:355–364. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.4.355.21424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Council Aids Working Committee Office & UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. 2004. A joint assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in China [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Freedberg KA, Sullivan LM, Savetsky J, Levenson SM, et al. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to partners. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:253–257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stempel RR, Moulton JM, Moss AR. Self-disclosure of HIV-1 antibody test results: The San Francisco General Hospital Cohort. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Wong C, Lee AM. Gender-related psychosocial and cultural factors associated with condom use among Chinese married women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13:329–342. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.4.329.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Press release, Stigma biggest hurdle to AIDS prevention in south Asia. Satellite session at XV international AIDS conference on critical themes for AIDS in south Asia; Bankock. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Von Massow F. ‘We are forgotten on earth’: International development targets, poverty and gender in Ethiopia. Gender and Development. 2000;8:45–54. doi: 10.1080/741923410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warszawshi J, Meyer L. Sex difference in partner notification: Results from three population based surveys in France. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78:45–49. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, et al. Willingness to participate in HIV/STD prevention intervention activities among rural-to-urban migrants in China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:557–570. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.6.557.53792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, et al. HIV-related risk factors associated with commercial sex among female migrants in China. Journal of Health Care for Women International. 2005;26:134–148. doi: 10.1080/07399330590905585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. The interplay of gender, space and work in China’s floating population. In: Entwisle B, Henderson GE, editors. Re-drawing boundaries: Work, households and gender in China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]