Abstract

Background

The 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of mRNA contains regulatory elements that are essential for the appropriate expression of many genes. These regulatory elements are involved in the control of nuclear transport, polyadenylation status, subcellular targetting as well as rates of translation and degradation of mRNA. Indeed, 3'-UTR mutations have been associated with disease, but frequently this region is not analyzed. To gain insights into congenital heart disease (CHD), we have been analyzing cardiac-specific transcription factor genes, including GATA4, which encodes a zinc finger transcription factor. Germline mutations in the coding region of GATA4 have been associated with septation defects of the human heart, but mutations are rather rare. Previously, we identified 19 somatically-derived zinc finger mutations in diseased tissues of malformed hearts. We now continued our search in the 609 bp 3'-UTR region of GATA4 to explore further molecular avenues leading to CHD.

Methods

By direct sequencing, we analyzed the 3'-UTR of GATA4 in DNA isolated from 68 formalin-fixed explanted hearts with complex cardiac malformations encompassing ventricular, atrial, and atrioventricular septal defects. We also analyzed blood samples of 12 patients with CHD and 100 unrelated healthy individuals.

Results

We identified germline and somatic mutations in the 3'-UTR of GATA4. In the malformed hearts, we found nine frequently occurring sequence alterations and six dbSNPs in the 3'-UTR region of GATA4. Seven of these mutations are predicted to affect RNA folding. We also found further five nonsynonymous mutations in exons 6 and 7 of GATA4. Except for the dbSNPs, analysis of tissue distal to the septation defect failed to detect sequence variations in the same donor, thus suggesting somatic origin and mosaicism of mutations. In a family, we observed c.+119A > T in the 3'-UTR associated with ASD type II.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that somatic GATA4 mutations in the 3'-UTR may provide an additional molecular rationale for CHD.

Background

GATA4 (MIM# 600576) is a transcription factor which is characterized by a highly conserved binding domain of two zinc fingers. It is expressed in the heart and is essential for mammalian cardiac development (see reviews [1-3]). In mice, germline ablation of the gene encoding Gata4 results in abnormal ventral folding of the embryo, failure to form a single ventral tube, and lethality [4,5]. Besides heart development, Gata4 is involved in the formation of multiple organs, such as intestine, liver, pancreas and swim bladder in zebrafish [6] as well as gastric epithelial development in mouse through interaction with Fog co-factors [7].

In humans, four GATA4 gene mutations have been identified in families with congenital heart defects (CHD) notably, atrial septal defects [8-11]. One mutation (p.Gly296Ser) affects a highly conserved amino acid after the C-terminal zinc finger, and disrupts physical interaction with TBX5 [8], a transcription factor described to be defective in Holt-Oram syndrome [12]. But GATA4 germline mutations are rather rare. Two studies analyzed 16 families each, but only 2/16 families with multiple affected members carried GATA4 mutations [10,11]. In 42 patients with non-syndromic atrioventricular septal defects (familial as well as sporadic), no GATA4 mutations have been detected [13].

It is of considerable importance that genetic analysis of blood samples may not reveal somatically-occurring sequence alterations in the diseased cardiac tissues, but these mutations may provide a molecular rationale for pathogenesis [14,15]. We recently reported evidence for somatically-derived NKX2-5 and TBX5 mutations as a novel mechanism for septation defects of the human heart [16-18], and used the same heart collection of malformed hearts to investigate GATA4 gene mutations, notably those affecting the coding of amino acids for zinc finger functions of the protein [19]. To identify further genetic alterations associated with CHD, we continued our search in the 609 bp of 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of GATA4.

The 3'-UTR of GATA4 is relatively long and likely contains regulatory elements essential for the regulation and transport of the mRNA transcript [20]. Indeed, evidence is accumulating that the 3'-UTR of mRNA is involved in the control of nuclear transport, polyadenylation status, subcellular targetting as well as rates of translation and degradation of mRNA; thus sequence alterations in this region may lead to disease (see review [21,22]). Recently, a single nucleotide deletion in the 3'-UTR of high mobility group A1 gene (HMGA1) was identified in two type 2 diabetes patients exhibiting deficiency of the protein [23]. The mutation decreased HMGA1 mRNA half life in the lymphoblast cells of the patients, and further deletion of the 3'-UTR of HMGA1 resulted in the decrease of reporter assay expression. To the best of our knowledge, the 3'-UTR of GATA4 has not been investigated particularly as regards its role in post-transcriptional gene expression. In this paper, we report the detection of frequent GATA4 sequence alterations in the 3'-UTR in the diseased tissues of malformed hearts, some of which are predicted to alter RNA secondary structure. As a result of aberrant RNA folding, these mutations may lead to CHD by affecting mRNA localization and translation of protein. We found further five nonsynonymous mutations in exons 6 and 7 of GATA4.

Results

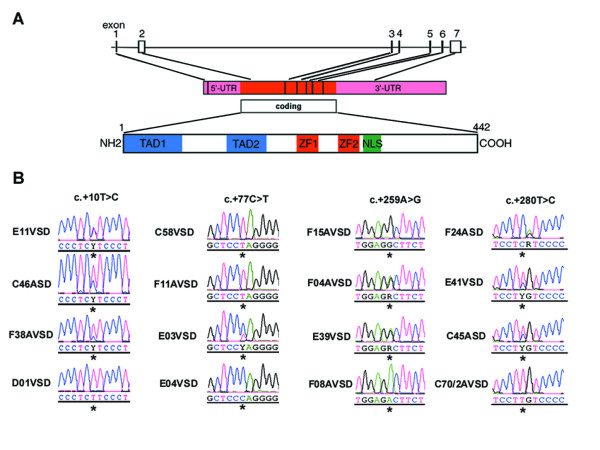

GATA4 is located on chromosome 8p23.1-p22, consists of seven exons and codes for a 442- amino-acid protein (see Fig. 1A). We investigated the genomic DNA for sequence variations in the entire coding region and untranslated regions (UTR) of this gene. In the case of formalin-fixed material, exons 3, 4, 6 and 7 of malformed hearts of patients with complex CHD could be amplified. We reported earlier the detection of 23 nonsynonymous mutations in exons 3 and 4, notably mutations affecting the zinc fingers of GATA4 [19]. Here we report further five nonsynonymous mutations in exons 6 and 7, which affect highly conserved amino acids 361, 377, 430, 432 and 442 in the C-terminal region of GATA4 (Table 2). Whether these sequence alterations result in aberrant protein expression requires additional studies. Previously, it has been shown that a frameshift mutation past amino acid 359 severely altered the encoded GATA4 protein and was associated with ASD [8]. Nonetheless, mutations p.Leu432Ser and p.Ala442Thr identified by us would affect polarity of the protein, due to replacement of non-polar, hydrophophic amino acids with polar, hydrophilic ones. In addition, p.Met361Val likely results in aberrant RNA folding, as determined by a method described below.

Figure 1.

Genetic analysis of GATA4. (A) Schematic representation of GATA4 (genomic, mRNA and protein level). Reference sequence for GATA4 was based on NM_002052 and the intron-exon boundaries on [42]. (B) Examples of 3'-UTR mutations and genotypes obtained after direct sequencing of fragments amplified from diseased cardiac tissues of patients affected by CHD. Additional sequence alterations in the 3'- UTR of GATA4 were detected, e.g. F24ASD (c.+281G>A).

Table 2.

Summary of GATA4 sequence variations in diseased cardiac tissues of patients with CHD

| Nucleotide change NM_002052 | Coding region | Amino acid change | Location | Positive hearts (n = 29 VSD) | Positive hearts (n = 16 ASD) | Positive hearts (n= 23 AVSD) | Total | PCR-RFLP assay |

| NONSYNONYMOUS** | ||||||||

| 1599 | c.1081A>G | p.Met361Val | exon 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1648 | c.1130G>A | p.Ser377Asn | exon 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1806 | c.1288C>G | p.Leu430Val | exon 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 1813 | c.1295T>C | p.Leu432Ser | exon 7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1842 | c.1324G>A | p.Ala442Thr | exon 7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3'UNTRANSLATED REGION | ||||||||

| 1857 | c.+10T>C | exon 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | EarlI | |

| 1891 | c.+44T>A | exon 7 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 1924 | c.+77C>T | exon 7 | 2* | 3* | 5 | Styl | ||

| 2065 | c.+218C>T | exon 7 | 1 | 3 | 4 | EarlI | ||

| 2106 | c.+259A>G | exon 7 | 1 | 1 | 2* | 4 | ||

| 2127 | c.+280T>C | exon 7 | 1 | 3* | 1 | 5 | ||

| 2289 | c.+442A>G | exon 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 2309 | c.+462T>C | exon 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 2326 | c.+479A>G | exon 7 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 3 | NarI | |

| 2201 | c.+354A>C | exon 7, dbSNPrs867858 | 27AA:2AC | 12AA:4AC | 19AA:3AC:1CC | 58AA:9AC:1CC | MspA1I | |

| 2273 | c.+426C>T | exon 7, dbSNPrs1062219 | 1CC:8CT:20TT | 2CT: 13TT | 1CC: 4CT:18TT | 2CC:14CT:51TT | ||

| 2364 | c.+517T>C | exon 7, dbSNPrs884662 | 9TT:16CT:4CC | 4TT:11CT | 4TT:15CT:4CC | 17TT:42CT:8CC | ||

| 2379 | c.+532T>C | exon 7, dbSNPrs904018 | 1TT:9CT:19CC | 9CT:6CC | 1TT:3CT:19CC | 2TT:21CT:44CC | ||

| 2410 | c.+563C>G | exon 7, dbSNPrs12825 | 15CC:8CG:6GG | 2CC:12CG | 15CC:6CG:2GG | 32CC:26CG:8GG | ||

| 2434 | c.+587A>G | exon 7, dbSNPrs804291 | 1AG:28GG | 13GG | 23GG | 1AG:64GG |

* homozygous genotypes observed

** nonsynonymous mutations in exons 3 and 4 reported earlier (Reamon-Buettner and Borlak, J Med Genet 42:e32)

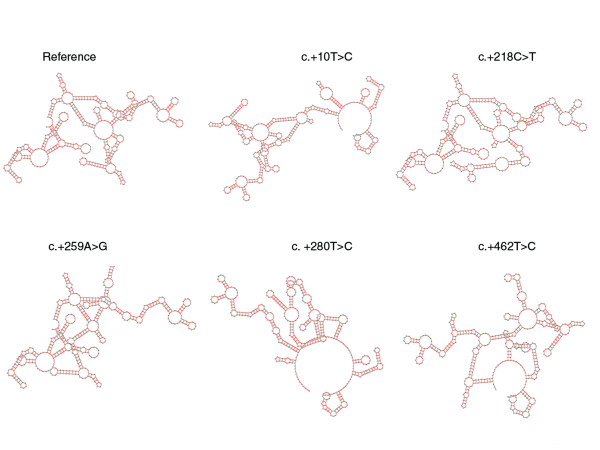

Notably, exon 7 of GATA4 consists of 1,708 bp, the majority (1,525 bp) being untranslated. From our collection of formalin-fixed hearts, we could amplify the first four fragments of exon 7 (see Fig. 1A and Table 1 for the primer sequences designated GTx7-1 to GTx7-4). These primer sequences cover a part of the coding region c.1221 to c.1329 (nt 1739–1847, NM_002052) and 3'-UTR from c.+1 to c.+609 (nt 1848–2456, NM_002052). We found 9 sequence alterations, occurring in 3 to 7 patients, and 6 dbSNPs in the analyzed 3'-UTR region of GATA4 (Table 2, Table 3). On the basis of sequence electropherograms and/or PCR-RFLP assays, both heterozygous and homozygous genotypes were observed (Fig. 1B). Using the program GeneQuest (Lasergene 6.0), we determined the effect of the nine sequence alterations on RNA folding. GeneQuest uses the Vienna RNA folding procedure, taken from Zuker's optimal RNA folding algorithm, to fold the sense strand of selected DNA regions as RNA. We investigated the first 500 bp of the 3'-UTR, simply because the sequence alterations identified by us are located within this segment. Furthermore, there is suggestion that the whole 3-'UTR is not necessary for localization, but that localization signals lie within the regions of < 100–200 nt [25]. Compared to the reference sequence, 7/9 of these would result in faulty RNA folding (Fig. 2). While c.+77C > T and c.+479A > G would likely not lead to faulty RNA folding, the same pattern was observed for c.+10T > C and c.+44T > A. In addition, we searched the 3'-UTR of GATA4 for highly conserved motifs that may be involved in post-transcriptional regulation, (see [26]). None of the conserved motifs reported so far have been detected, but the highly conserved motif (AATAAA) associated with polyadenylation signals were located at positions c.+678–683 and c.+1502–1507.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions used for analysis of GATA4 mutations

| GATA4 exons | Exon size (bp) | Primer | Primer length | Primer sequence (5'-3') | Melting temperature | PCR product length (bp) |

| exon 1 | 61 | GT4x1F | 20 | cttgcacgtgactcccacag | 65°C | 250 |

| GT4x1R | 20 | aagcaaaggcggagaagctc | ||||

| exon 2 | 1073 | GT4x2-1F | 21 | tctctttctgtcgttcctctt | 65°C | 600 |

| GT4x2-1R | 20 | gcacgtagactggcgaggac | ||||

| GT4x2-2F | 21 | ggaccatgtatcagagcttgg | 65°C | 641 | ||

| GT4x2-2R | 20 | gccctcgcgctcctactcac | ||||

| exon 3 | 167 | GT4x3F | 24 | agtcagagtgaggaagagcaagag | 65°C | 541 |

| GT4x3R | 21 | cagtttctgtgtgccgaagag | ||||

| exon 4 | 126 | GT4x4F | 20 | ccagccctgcctcccgttag | 65°C | 294 |

| GT4x4R | 23 | gaggactgagagatgggcatcag | ||||

| exon 5 | 88 | GT4x5F | 22 | agtagccatcacatcacacagg | 65°C | 504 |

| GT4x5R | 19 | aaagctcccaacacgttcc | ||||

| exon 6 | 149 | GT4x6F | 20 | gtttgtccctgccgctgatt | 65°C | 247 |

| GT4x6R | 20 | gcagtcggcctccccacaaa | ||||

| exon 7 | 1708 | GTx7-1F | 19 | acaaggctatgcgtctccc | 60°C | 289 |

| GTx7-1R | 20 | ctgagaaaatccaacacccg | ||||

| GT4x7-2F | 20 | gcgtaatcttccctcttccc | 65°C | 291 | ||

| GT4x7-2R | 19 | gggacaaggacatcttggg | ||||

| GTx7-3F | 20 | gtcgacaatctggttagggg | 60°C | 281 | ||

| GTx7-3R | 20 | gtacatggcaaacagatgcc | ||||

| GTx7-4F | 20 | gaggatctgagaacaagcgg | 60°C | 270 | ||

| GTx7-4R | 20 | cagctgcattttgatgaggc | ||||

| GTx7-5F | 22 | aaattgtggggtgtgacataca | 60 °C | 577 | ||

| GTx7-5R | 22 | gttgcagaatctctggcttttt | ||||

| GTx7-6F | 22 | ctgtctgtctgctcctcctagc | 65°C | 586 | ||

| GTx7-6R | 22 | acctcccagtgaagaccactaa |

Table 3.

Spectrum of GATA4 mutations (nonsynonymous and 3'-UTR) in diseased tissues of malformed hearts

| Patient | Age | Total defects* | Detected mutations | ||

| Coding (ns)*** | 3'-UTR | Total | |||

| VSDs | |||||

| C06VSD** | 1h | 3 | F211L, Y244C, R260Q, C292R | 4 | |

| C10VSD | stillborn | 6 | C292R | 1 | |

| C19VSD | 3 mo | 4 | C292R | 1 | |

| C58VSD | 18 d | 5 | C292R | c.+77C>T | 2 |

| D01VSD | aborted | 3 | C292R | 1 | |

| D03VSD | 2 mo | 4 | C292R | 1 | |

| E03VSD** | 6 mo | 2 | c.+77C>T | 1 | |

| E04VSD** | 5 wk | 2 | C292R | 1 | |

| E08VSD | 53 yr | 1 | C292R | 1 | |

| E10VSD | 6 mo | 4 | G214S | 1 | |

| E11VSD | newborn | 1 | c.+10T>C | 1 | |

| E13VSD | 16 yr | 1 | N239S, C292R | 2 | |

| E15VSD | 8 mo | 2 | N239D | 1 | |

| E16VSD | 3 mo | 3 | M361V | 1 | |

| E20VSD | 2 d | 3 | 0 | ||

| E22VSD | 4 mo | 3 | F208L, C292R | 2 | |

| E23VSD** | 22 d | 3 | L261P, C292R | 2 | |

| E26VSD | 6 mo | 3 | C292R, S377N | c.+479A>G | 3 |

| E27VSD | 5 mo | 2 | M223T, R229S, C292R | c.+462T>C | 4 |

| E28VSD | 5 mo | 2 | c.+44T>A | 1 | |

| E29VSD | 8 wk | 3 | C292R | 1 | |

| E31VSD | 5 mo | 2 | 0 | ||

| E33VSD | 14 yr | 1 | A442T | 1 | |

| E34VSD | 3 mo | 2 | 0 | ||

| E35VSD | 4.5 mo | 2 | C292R | 1 | |

| E39VSD | 9 mo | 3 | C292R | c.+218C>T, c.+259A>G | 3 |

| E40VSD | 15 mo | 1 | C292R | 1 | |

| E41VSD | 23 yr | 2 | C292R | c.+280T>C | 2 |

| E49VSD | newborn | 3 | C292R | c.+442A>G | 2 |

| ASDs | |||||

| C09ASD | 26 yr | 2 | 0 | ||

| C39ASD | 25 yr | 4 | C292R | 1 | |

| C45ASD | 6 d | 7 | C292R, L432S | c.+280T>C, c.+462T>C | 4 |

| C46ASD | 34 yr | 3 | C292R | c.+10T>C, c.+259A>G, c.+462T>C | 4 |

| C64ASD | 11 mo | 4 | C292R | 1 | |

| C75ASD | 2 mo | 6 | C292R | 1 | |

| D30ASD | 11 yr | 3 | L430V | 1 | |

| D33ASD | 8 yr | 2 | N248S, L261P | c.+462T>C, c.+479A>G | 4 |

| F17ASD | 4 1/2 h | 1 | c.+280T>C | 1 | |

| F19ASD | 8 yr | 4 | c.+462T>C | 1 | |

| F20ASD | 10 yr | 1 | 0 | ||

| F24ASD | 6 yr | 3 | c.+280T>C | 1 | |

| 27ASD | 7 yr | 2 | C292R | c.+442A>G | 2 |

| F29ASD | 14 yr | 8 | I255T, A294V | c.+10T>C | 3 |

| F30ASD | 1 d | 2 | 0 | ||

| F32ASD | 38 yr | 1 | R229S | 1 | |

| AVSDs | |||||

| C43AVSD | 10 mo | 7 | H302R | c.+10T>C | 2 |

| C70/2AVSD** | 8 mo | 6 | G234S, R252P, C292R | 3 | |

| C71AVSD** | 4 d | 5 | c.+10T>C, c.+442A>G | 2 | |

| E05AVSD | 16 wk | 6 | c.+10T>C | 1 | |

| E36AVSD** | 3.5 mo | 4 | 0 | ||

| E43AVSD | 4.5 mo | 4 | R283H | 1 | |

| F00AVSD** | 6 wk | 5 | c.+44T>A, c.+218C>T | 2 | |

| F02AVSD | 10 mo | 7 | N248S | c.+77C>T | 2 |

| F03AVSD** | 1 mo | 4 | c.+44T>A | 1 | |

| F04AVSD** | 11 wk | 5 | C292R | c.+218C>T, c.+259A>G | 3 |

| F05AVSD** | 10 wk | 4 | F211L, R229S, Y244C, N285K | 4 | |

| F08AVSD** | 5 mo | 5 | P226fs | 1 | |

| F11AVSD** | 7 mo | 6 | C292R | c.+77C>T | 2 |

| F12AVSD | 6 mo | 5 | R266X | 1 | |

| F13AVSD** | 25 mo | 5 | C292R | 1 | |

| F14AVSD** | 1 mo | 5 | T277I, C292R | 2 | |

| F14aAVSD** | 5 wk | 5 | c.+462T>C | 1 | |

| F15AVSD | 5 d | 7 | c.+218C>T, c.+259A>G | 2 | |

| F18AVSD** | 7 mo | 5 | 0 | ||

| F28AVSD | 8 yr | 3 | N273S, L430V | 2 | |

| F31AVSD** | 8 d | 6 | c.+479A>G | 1 | |

| F38AVSD | 3 mo | 4 | C292R | c.+10T>C, c.+77C>T, c.+280T>C | 4 |

| F40AVSD | 10 mo | 3 | c.+44T>A | 1 | |

* Heart malformations described earlier in Reamon-Buettner et al. 2004 Am J Pathol 2004, 164:2117–2125.

** Down syndrome

*** nonsynonymous GATA4 mutations in exons 3 and 4 reported earlier in Reamon-Buettner and Borlak 2005, J Med Genet 42:e32; new mutations detected in exons 6 and 7 are in bold

Figure 2.

Effect of mutations in the 3'-UTR of GATA4 on mRNA folding. Using the program GeneQuest (Lasergene 6.0), the effect of sequence alterations on RNA folding was predicted using the first c.+500 nt in the 3'-UTR of GATA4. GeneQuest uses the Vienna RNA folding procedure, taken from Zuker's optimal RNA folding algorithm [43], to fold the sense strand of selected DNA regions as RNA. Compared to the reference sequence, 7/9 mutations would result in faulty RNA folding, on which five patterns here are shown. Same pattern was observed for c.+10 T > C and c.+44T > A.

To compare healthy vs. diseased tissues from each patient, we selected specifically those who were positive for mutations in the diseased tissue. For instance, in the diseased tissues, we found 17/68 patients without nucleotide changes in analyzed region of the 3'-UTR except for the dbSNPs. Thus for this comparison, we analyzed 21 patients for GTx7-1 (21 × 2 × 289 bp = 12,138 nucleotides); 25 patients for GTx7-3 (25 × 2 × 281 bp = 14,050 nucleotides) and 24 patients for GTx7-4 (24 × 2 × 270 bp = 12,960 nucleotides). Except for the dbSNPs rs867858, rs1062219, rs884662, rs904018, rs12825 (see Table 2), none of the mutations were detected in the unaffected tissues. This result suggests somatic origin and mosaicism of mutations.

In the formalin-fixed malformed hearts, we observed six dbSNPs which were all located within 234 nucleotides in exon 7 (Table 2). We could calculate the allele frequencies for five loci (Table 2) and found the dbSNPs to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We cloned three fragments from hearts heterozygous for rs1062219 (c.+426C > T), rs884662 (c.+517T > C) and rs904018 (c.+532T > C). Surprisingly, we found three haplotypes after sequencing of at least four clones in each heart. In all three hearts, we found one type containing all reference alleles [c.+426C; c.+517T; c.+532T] and another type with all variant alleles [c.+426T; c.+517C; c.+532C]. Additional types found were [c.+426T; c.+517T; c.+532T] with one variant allele, and [c.+426C; c.+517C; c.+532C] with two variant alleles.

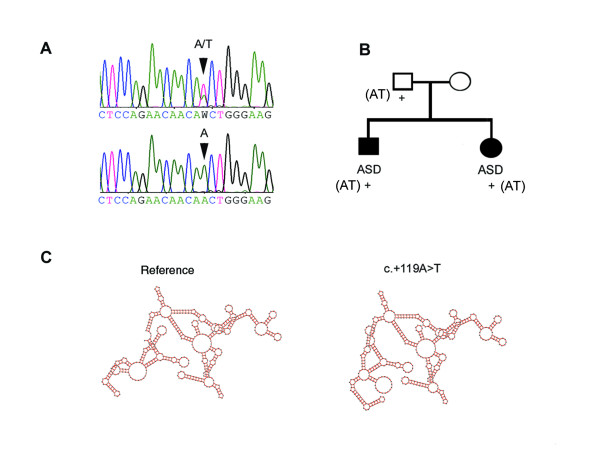

We further analyzed the entire gene in blood samples of 12 patients with CHD (see Fig. 1A). Mostly dbSNPs were detected (Table 4); nonetheless we observed two sequence variations in the 3'-UTR (c.+119A > T and c.+1260G > A) and two intronic (c.-518-25C > T and c.-458+5A > G) which have not yet been reported as dbSNPs. The 3'-UTR alterations and c.-518-25C>T were detected in a family of four, in which the two children were affected by ASD, but the parents had no history of CHD. For c.+119A>T, the mother was homozygous for the reference allele AA, while the father and the children had the heterozygous genotype AT (Fig. 3A&B). This sequence variation would affect RNA folding (Fig. 3C). As control, we analyzed blood samples from 100 unrelated Caucasian healthy individuals. No sequence variations were found, except for a synonymous change in exon 3 (c.699G>A, p.233Thr), an intronic (c.783+16G>A) and dbSNPs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of GATA4 sequence variations in blood samples

| Nucleotide change NM_002052 | Coding region | Amino acid change | Location | NCBI dbSNP number | Blood samples CHD | Blood samples normal |

| NONSYNONYMOUS | ||||||

| 1647 | c.1129A>G | p.Ser377Gly | exon 6 | rs3729856 | 10AA:2AG | |

| SYNONYMOUS | ||||||

| 1217 | c.699G>A | p.Thr233 | exon 3 | 1 (GA) | ||

| 3'-UTR | ||||||

| 1967 | c.+119A>T | exon 7 | 2 (AT) | |||

| 3107 | c.+1260G>A | exon 7 | 1 (GA) | |||

| 2201 | c.+354A>C | exon 7 | rs867858 | 3AA:9AC | 53AA:36AC:11CC | |

| 2273 | c.+426C>T | exon 7 | rs1062219 | 1CC:8CT:3TT | 39CC:38CT:23TT | |

| 2364 | c.+517T>C | exon 7 | rs884662 | 4TT:5CT:3CC | 43TT:30CT:27CC | |

| 2379 | c.+532T>C | exon 7 | rs904018 | 1TT:5CT: 6CC | 30TT: 30CT:40CC | |

| 2410 | c.+563C>G | exon 7 | rs12825 | 8CC:3CG:1GG | 69CC:11CG:20GG | |

| 2434 | c.+587A>G | exon 7 | rs804291 | 12GG | 100 GG | |

| 3005 | c.+1158C>T | exon 7 | rs11785481 | 7CC:5CT | ||

| 3103 | c.+1256A>T | exon 7 | rs12458 | 3AA:9AT | ||

| 3202 | c.+1355G>A | exon 7 | rs1062270 | 11GG:1AG | ||

| 3368 | c.+1521G>C | exon 7 | rs3293358 | 5CC:6CG:1GG | ||

| INTRONIC | ||||||

| c.-518-25C>T | intron | 2 (1CT:1TT) | ||||

| c.-458+5A>G | intron | 1 (AG) | ||||

| c.783+16G>A | intron | 1 (GA) | ||||

| c.614-61G>C | intron | rs10503425 | 8GG:3CG:1CC | 27AA:12AC:3CC | ||

| c.997+56A>C | intron | rs804280 | 3AA:7AC:2CC |

Figure 3.

Detection of 3'-UTR mutations in blood samples of patients with CHD. (A) sequence electropherograms for c.+119A>T, showing heterozygous (AT) and homozygous (AA) genotypes; (B) in a family of four in which the two children had ASD; the father and the children had the heterozygous genotype AT (+), the mother was homozygous for the reference allele AA; (C) Compared to the reference sequence and on the basis of Vienna RNA folding procedure, c.+119A>T is predicted to affect RNA folding.

Discussion

Recent studies characterize further the importance of Gata4 in cardiac development. Indeed, small changes in the level of Gata4 protein expression can dramatically influence cardiac morphogenesis and embryonic survival [27]. Moreover, myocardial expression of Gata4 is required for proliferation of cardiomyocytes, formation of the endocardial cushions, development of the right ventricle, and septation of the outflow tract [28]. To gain further insights into the role of GATA4 mutations in CHD in humans, we have analyzed the Leipzig collection of malformed hearts for sequence alterations of this gene. We reported previously the identification of 23 nonsynonymous mutations, 19 of which are located within the highly conserved zinc fingers and basic regions of GATA4 [19]. Notably, we identified a frequent mutation (p.Cys292Arg) in VSDs, which affects one of the four zinc coordinating cysteines in the C-finger and is predicted to disrupt the secondary structure of the protein. Functional characterization of site-directed mutated residues in the C-finger, showed that disruption of the zinc coordinating cysteines, would abolish DNA binding, Gata4-Nkx2-5 interactions and synergy [29,30].

To identify genetic alterations associated with CHD, we continued our search for mutations in the 3'-UTR region of GATA4. In the diseased tissues of malformed hearts, we found frequent alterations in the 3'-UTR of GATA4, in which 7/9 would affect RNA folding. Additional sequence alterations in the 3'- UTR of GATA4 were detected, but these were mostly isolated cases and therefore not reported here. Further, we identified a germline mutation (c.+119A>T) in which two affected family members were positive. Similarly, it would alter RNA folding. Since the unaffected father carried c.+119A>T, we cannot discount the possibilities of a low penetrance mutation or no causal association at all. Whether the 3'-UTR mutations reported here contributed to cardiac malformations by affecting the secondary structure of mRNA or through other post-transcriptional regulation associated with 3'-UTR, requires further functional analysis. Nonetheless, it has been shown that two mutations in the 3'-UTR of rat Mti (metallothionein-1) that are predicted to alter the secondary structure of this region also impaired localization of the mRNA [25].

There is, however, accumulating evidence on the important role of 3'-UTR in post-transcriptional regulation. For instance, efficient termination and stability of mRNA are dependent on a properly configured 3'-UTR [31]. Localization of mRNAs is also due to specific sites or signals within the 3'-UTR [25,32]. Recently, a systematic search discovered 106 highly conserved motifs in human 3'-UTRs that may be involved in post-transcriptional regulation, including mRNA stability and degradation [26]. Many of these are associated with microRNAs, which are non-coding RNAs of 21–22 nucleotides and are complementary to the 3'-UTR motifs that mediate post-transcriptional regulation [33]. Similary, 53 sequence motifs have been catalogued in 3'-UTR of yeast mRNAs, including motifs corresponding to known RNA-binding protein sites and motifs associated with subcellular localization [34]. Furthermore, 83 disease-associated variants in the 3'-UTR of human protein-coding genes have been systematically analyzed, and that functionality of these variants correlated highly to predicted secondary structural changes [35].

Many studies are suggestive for Gata4 to network with other transcription factors to regulate cardiac gene expression (see reviews [1-3]). These protein-protein interactions are mediated through the proteins' binding domains and for Gata4, the zinc fingers are involved. For instance, N-terminal zinc finger interacts with Fog2, while the C-terminal zinc finger contacts Nkx2-5, Nf-At3, Mef2c and Hand2. Notably, the C-finger of Gata4 interacts with the third alpha helix (homeodomain) of Nkx2-5, to enable transcriptional synergy of regulated genes. Site-directed mutagenesis of zinc coordinating cysteines in the C-finger leads to abrogation of Gata4-Nkx2-5 interaction and loss of synergy [29,30]. We reported previously the identification of somatically-derived GATA4 zinc finger mutations in the same malformed hearts, including a frequent mutation (p.Cys292Arg) in VSDs, which affects one of the four zinc coordinating cysteines and is predicted to disrupt the secondary structure of the protein [19]. However, aside from p.Cys292Arg and unlike NKX2-5 [16,17] common nonsynonymous mutations are rare in the coding regions of GATA4. Thus, the further detection of mutations in the 3'-UTR of GATA4 in the same malformed hearts with zinc finger mutations suggests a possible further mechanisms of disease, in which the zinc fingers are not involved. Indeed, as shown in Table 3, in which GATA4 nonsynonymous and 3'-UTR mutations identified in hearts with septation defects are summarized, there were 14 with 3'-UTR mutations only. These consist of 3 in VSDs, 3 in ASDs, and 8 in AVSDs. From these 14 hearts, 12 carried 3'-UTR mutations that are predicted to result in aberrant RNA folding. As can be surmised from Table 3, it appears that 3'-UTR mutations are more frequent in ASDs and AVSDs than in VSDs. In VSDs, 23 out of 29 had mutations in the coding region, most of which were p.Cys292Arg and only 9 out of 29, carried 3'-UTR mutations. It is also of considerable interest that sporadic cases of CHD from Lebanese population were analyzed for mutations affecting the zinc fingers and basic region of GATA4 [36]. A mutation (p.Glu216Asp) in the N-terminal zinc finger was detected in 2/26 patients with Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), and this mutation resulted in reduced transcriptional activity without affecting GATA4's ability to bind DNA, nor its interaction with ZFPM2 (FOG2). However, none of the other 94 patients with various CHD phenotypes carried any mutations.

To help elucidate genetic alterations in affected tissues of malformed hearts, we have investigated in the past a panel of cardiac transcription factor genes from the same 68 malformed hearts [16-19,37]. Direct sequencing revealed mutations in diseased tissues, which were basically absent in matched normal heart samples. Common occurring mutations were identified, especially in the binding domains of transcription factors, which could affect DNA-protein or protein-protein interactions leading to CHD. While certain transcription factor genes (NKX2-5, GATA4) exhibited a high rate of mutations, others were not or rarely affected (HEY2, MEF2C). Results of these studies enabled us to put forward a hypothesis of somatic mutations as a novel molecular cause of CHD. Furthermore, we found malformed hearts containing combination of mutations in the binding domains of several transcription factors, As example, we identified in two patients with AVSD combined mutations in the binding domains of HEY2, NKX2-5, TBX5 and GATA4 [37]. We also identified 21 patients with combined mutations in the GATA4 zinc fingers and the homeodomain of NKX2-5 (unpublished results).

Our malformed hearts were stored in formalin more than 40 years ago and there is speculation about artifacts arising from this procedure [38-40]. To ensure reliability of our findings, we investigated sequence variations in 10 formalin-fixed, but healthy hearts which were collected at the same time as the malformed hearts. Essentially, these hearts were free of GATA4 mutations, therefore providing convincing evidence for reliability of the assay. In addition, our identification of six dbSNPs within the 3'-UTR demonstrates faithful preservation of DNA and reliability in using valuable retrospective material with the obvious advantage of studying clearly defined pathology, as opposed to using surrogate tissue material distal to organ defect. Five dbSNPs were highly polymorphic (see Table 2) and were found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. This was confirmed with our control population of healthy individuals. But cloning of fragments amplified from diseased heart tissues of patients who were 'heterozygous' for three dbSNPs detected three haplotypes instead of the expected two, which may be due to duplication of GATA4 in analyzed tissues.

This result is similar to our previous observations on different cardiac transcription factors conducted on the same set of malformed hearts [16-19,37]. After cloning amplified fragments with several closely-spaced 'heterozygous' mutations as marker loci within a single gene, we observed several haplotypes in individual hearts, instead of two haplotypes as expected of a diploid genome. (Note, we used the term haplotype to define the set of alleles within an investigated gene locus). The cause of the observed multiple haplotypes is unknown, but may be explained by a mixed population of cardiomyocytes carrying different mutations or de novo chromosomal rearrangements and gene duplications in the heart tissues of patients affected by CHD. Our results for NKX2-5 by using a yeast-based assay to determine function suggest that different haplotypes can lead to different cardiac disease phenotypes [41]. Furthermore, the presence of combined mutant alleles may alter/modify pattern of mRNA folding. We found, for instance, patients who were either positive for c.+218C>T or c.+259 A>G or both. Two patients were heterozygous for both mutations, while one patient was homozygous for both variant alleles. Singly c.+218C>T or c.+259 A>G would lead to misfolding (see Fig. 2), but if combined only the pattern observed for c.+259 A>G would result. Moreover, different haplotypes due to combinations of closely-spaced polymorphisms in the 3'-UTR of genes can result in different mRNA stabilities in transient expression assays [35]. Nonetheless, as the malformed hearts were conserved in formalin, possibilities exist that the observed multiple haplotypes could be PCR errors resulting from fragmented DNA. We believe the contrary, however, as specific haplotypes were detected in several malformed hearts after cloning, but were absent in matched unaffected heart tissue (unpublished results).

To further support DNA assay reliability on the formalin-fixed material, we examined in the course of our work with the Leipzig heart collection, additional genes which have been associated with cardiac malformations. We searched for sequence variations affecting the binding domains of MEF2C and HEY2. In the case of MEF2C gene, no nonsynonymous mutations have been detected in a total of 68 patients with complex CHD (unpublished results). A similar finding was observed with the HEY2 gene, where only three nonsynonymous mutations were found in 2 of 52 patients [37]. Our work on TBX5 in the same heart collection likewise supports reliability of using the material [18]. Mutations in this T-box transcription factor has been associated with Holt-Oram syndrome (HOS), a disorder characterized by heart and upper limb deformities [12]. We amplified 200, 307, 276, 203 and 515 bp containing exons 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8, respectively in the same heart collection. The sequences encoding the T-box are located in exons 3, 4 and 5. We found a total of nine nonsynonymous mutations distributed in few patients with ASDs and AVSDs. None of the 29 VSDs carried any nonsynonymous mutations, only two synonymous mutations were found in two patients. To assess further method reliability, we investigated in the same patient cohort amplified fragments from other genes, with or without prior implication to heart development (e.g. CFC1, HMGN4 and BRCC2), in the same heart collection, as well as in formalin-fixed normal mouse heart s (e.g. Hand1, Nkx2-5 and Gata4) but did not find sequence alterations [37].

Conclusion

We identified hotspots associated with cardiac defects in the 3'-UTR region. Our results suggest that somatic GATA4 mutations in the 3'-UTR may provide an additional molecular rationale for CHD

Methods

Materials, genomic DNA isolation, and mutation detection have been described previously [16]. Briefly, we analyzed 68 formalin-fixed hearts of Caucasians with complex cardiac malformations, notably n = 29 with ventricular (VSD), n = 16 with atrial (ASD), and n= 23 with atrioventricular (AVSD) septal defects. The explanted hearts, which were collected between 1954–1982, were obtained from the Institute of Anatomy, University of Leipzig, Germany. We also analyzed blood samples of 12 Caucasian patients with CHD, and blood samples of 100 unrelated healthy Caucasian individuals. In blood samples, defects of patients with CHD included VSD, ASD, hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), transposition of the great arteries (TGA), sub-pulmonary stenosis (SPS) and heterotaxy. Except for two patients who came from the same family, 10/12 patients were unrelated individuals. In the formalin-fixed malformed hearts, diseased tissues in the vicinity of the septal defects were analyzed. Matched healthy heart tissues were likewise investigated for sequence alterations. Materials used in this study were obtained in accordance to an approved protocol. JB has obtained approval to conduct genetic studies involving human materials from the Medical School Hannover. The formalin-fixed hearts were collected more than 40 years ago and cadavers were donated voluntarily by patients' relatives.

The primers and PCR conditions used in investigating sequence variations of GATA4 are given in Table 1. PCR-amplified fragments were sequenced directly using BigDyeTerminator v3.1 Kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) and Applied Biosystems 3100 Genetic Analyzer. Sequences were analyzed using SeqScape 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) or DNASTAR Lasergene 6.0 (Madison, Wisconsin USA). The numbering of mutations within the coding region of GATA4 starts with nucleotide A of the first codon ATG, while that in the untranslated region was based on NM_002052. Nucleotide changes in the untranslated and intronic regions were numbered according to suggested nomenclature [24]. Sequence variations were verified by independent PCR, double-strand sequencing, PCR-RFLP, or cloning of heterozygous genotypes followed by subsequent sequencing of clones, allowing the identification of variant alleles. Unless reported as NCBI dbSNPs, we refer to nucleotide changes as sequence variations or mutations interchangeably, which simply means deviations from the reference GATA4 sequence (NM_002052), and disease-causing or not.

Abbreviations

CHD Congenital heart disease

ASD Atrial septal defect

VSD Ventricular septal defect

AVSD Atrioventricular septal defect

UTR Untranslated region

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SMRB participated in the conceptual design of the study, was responsible for the lab work, carried out analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. SHC participated in the screening, confirmation, and analysis of mutations as part of her M.D. project. JB was in-charge of the conceptual design of the study, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the final writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institute of Anatomy, University of Leipzig for providing the heart collection, the Department of Cardiac Surgery and Pediatric Cardiology, University of Mainz for the blood samples of patients with CHD, Annika Roskowetz and Andreas Hiemisch for technical support. The financial support to JB of the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture is greatly appreciated.

Contributor Information

Stella Marie Reamon-Buettner, Email: reamon-buettner@item.fraunhofer.de.

Si-Hyen Cho, Email: borlak@item.fraunhofer.de.

Juergen Borlak, Email: borlak@item.fraunhofer.de.

References

- Molkentin JD. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38949–38952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikkarainen S, Tokola H, Kerkela R, Ruskoaho H. GATA transcription factors in the developing and adult heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temsah R, Nemer M. GATA factors and transcriptional regulation of cardiac natriuretic peptide genes. Regul Pept. 2005;128:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CT, Morrisey EE, Anandappa R, Sigrist K, Lu MM, Parmacek MS, Soudais C, Leiden JM. GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1048–1060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Lin Q, Duncan SA, Olson EN. Requirement of the transcription factor GATA4 for heart tube formation and ventral morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1061–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzinger A, Evans T. Gata4 regulates the formation of multiple organs. Development. 1997. pp. 4005–4014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen CM, Mannisto S, Porter-Tinge S, Genova E, Parviainen H, Heikinheimo M, Adameyko II, Tevosian SG, Wilson DB. GATA-4:FOG interactions regulate gastric epithelial development in the mouse. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:355–362. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V, Kathiriya IS, Barnes R, Schluterman MK, King IN, Butler CA, Rothrock CR, Eapen RS, Hirayama-Yamada K, Joo K, Matsuoka R, Cohen JC, Srivastava D. GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5. Nature. 2003;424:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo A, Miyoshi O, Baba K, Takagi M, Tsukamoto K, Kinoshita A, Yoshiura K, Kishino T, Ohta T, Niikawa N, Matsumoto N. A novel GATA4 mutation completely segregated with atrial septal defect in a large Japanese family. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e97. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.018895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkozy A, Conti E, Neri C, D'Agostino R, Digilio MC, Esposito G, Toscano A, Marino B, Pizzuti A, Dallapiccola B. Spectrum of atrial septal defects associated with mutations of NKX2.5 and GATA4 transcription factors. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e16. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.026740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama-Yamada K, Kamisago M, Akimoto K, Aotsuka H, Nakamura Y, Tomita H, Furutani M, Imamura S, Takao A, Nakazawa M, Matsuoka R. Phenotypes with GATA4 or NKX2.5 mutations in familial atrial septal defect. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:47–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson CT, Bachinsky DR, Lin RC, Levi T, Elkins JA, Soults J, Grayzel D, Kroumpouzou E, Traill TA, Leblanc-Straceski J, Renault B, Kucherlapati R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Mutations in human TBX5 cause limb and cardiac malformation in Holt-Oram syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:30–35. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkozy A, Esposito G, Conti E, Digilio MC, Marino B, Calabro R, Pizzuti A, Dallapiccola B. CRELD1 and GATA4 gene analysis in patients with nonsyndromic atrioventricular canal defects. Am J Med Genet. 2005;139:236–238. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson RP. Somatic gene mutation and human disease other than cancer. Mutat Res. 2003;543:125–136. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(03)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzelova E, Vonarbourg C, Stolzenberg MC, Arkwright PD, Selz F, Prieur AM, Blanche S, Bartunkova J, Vilmer E, Fischer A, Le Deist F, Rieux-Laucat F. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with somatic Fas mutations. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1409–1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamon-Buettner SM, Hecker H, Spanel-Borowski K, Craatz S, Kuenzel E, Borlak J. Novel NKX2-5 mutations in diseased heart tissues of patients with cardiac malformations. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:2117–2125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63770-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J. Somatic NKX2-5 mutations as a novel mechanism of disease in complex congenital heart disease. J Med Genet. 2004;41:684–690. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.017483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J. TBX5 mutations in Non-Holt-Oram Syndrome (HOS) malformed hearts. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:104. doi: 10.1002/humu.9255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J. GATA4 zinc finger mutations as a molecular rationale for septation defects of the human heart. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e32. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.025395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh J. 3'-Untranslated regions are important in mRNA localization and translation: lessons from selenium and metallothionein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:990–993. doi: 10.1042/BST03209990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conne B, Stutz A, Vassalli JD. The 3' untranslated region of messenger RNA: A molecular 'hotspot' for pathology? Nat Med. 2000;6:637–641. doi: 10.1038/76211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama A, Cook EH, Jr, Feng J, Glanzmann C, Yan J, Craddock N, Jones IR, Goldman D, Heston LL, Sommer SS. MECP2 structural and 3'-UTR variants in schizophrenia, autism and other psychiatric diseases: a possible association with autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;128:50–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Chiefari E, Fedele M, Iuliano R, Brunetti L, Paonessa F, Manfioletti G, Barbetti F, Brunetti A, Croce CM, Fusco A, Brunetti A. Lack of the architectural factor HMGA1 causes insulin resistance and diabetes in humans and mice. Nat Med. 2005;11:765–773. doi: 10.1038/nm1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nury D, Chabanon H, Levadoux-Martin M, Hesketh J. An eleven nucleotide section of the 3'-untranslated region is required for perinuclear localization of rat metallothionein-1 mRNA. Biochem J. 2005;387:419–428. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, Mootha V, Lindblad-Toh K, Lander ES, Kellis M. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3' UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu WT, Ishiwata T, Juraszek AL, Ma Q, Izumo S. GATA4 is a dosage-sensitive regulator of cardiac morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;275:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg EM, Ma Q, Juraszek AL, Moses K, Schwartz RJ, Izumo S, Pu WT. Morphogenesis of the right ventricle requires myocardial expression of Gata4. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1522–1531. doi: 10.1172/JCI23769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Shioi T, Kasahara H, Jobe SM, Wiese RJ, Markham BE, Izumo S. The cardiac tissue-restricted homeobox protein Csx/Nkx2.5 physically associates with the zinc finger protein GATA4 and cooperatively activates atrial natriuretic factor gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3120–3129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda JL, Belaguli N, Nigam V, Chen CY, Nemer M, Schwartz RJ. GATA-4 and Nkx-2.5 coactivate Nkx-2 DNA binding targets: role for regulating early cardiac gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3405–3415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrani N, Ganesan R, Kervestin S, Mangus DA, Ghosh S, Jacobson A. A faux 3'-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature. 2004;432:112–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickleburgh I, Burtle B, Hollas H, Campbell G, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z, Vedeler A, Hesketh J. Annexin A2 binds to the localization signal in the 3' untranslated region of c-myc mRNA. FEBS J. 2005;272:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3' UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalgi R, Lapidot M, Shamir R, Pilpel Y. A catalog of stability-associated sequence elements in 3' UTRs of yeast mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-10-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Ferec C, Cooper DN. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3' regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes II: the importance of mRNA secondary structure in assessing the functionality of 3' UTR variants. Hum Genet. 2006;120:301–333. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemer G, Fadlalah F, Usta J, Nemer M, Dbaibo G, Obeid M, Bitar F. A novel mutation in the GATA4 gene in patients with Tetralogy of Fallot. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:293–294. doi: 10.1002/humu.9410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J. HEY2 mutations in malformed hearts. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:118. doi: 10.1002/humu.9390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, DiCioccio RA, Allen HJ, Werness BA, Piver MS. Mutations in BRCA1 from fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue can be artifacts of preservation. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;107:21–27. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(98)00079-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C, Ponten F, Moberg C, Soderkvist P, Uhlen M, Ponten J, Sitbon G, Lundeberg J. A high frequency of sequence alterations is due to formalin fixation of archival specimens. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65461-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievre A, Landi B, Cote JF, Veyrie N, Zucman-Rossi J, Berger A, Laurent-Puig P. Absence of mutation in the putative tumor-suppressor gene KLF6 in colorectal cancers. Oncogene. 2005;24:7253–7256. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inga A, Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J, Resnick MA. Functional dissection of sequence-specific NKX2-5 DNA binding domain mutations associated with human heart septation defects using a yeast-based system. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1965–1975. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GeneView http://www.ensembl.org/Homosapiens/geneview

- Zuker's RNA folding algorithm http://www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/~zukerm/seqanal/