Abstract

Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor (VDR) are resistant to airway inflammation. Pathogenic immune cells capable of transferring experimental airway inflammation to wildtype (WT) mice are present and primed in the VDR KO mice. Furthermore, the VDR KO immune cells homed to the WT lung in sufficient numbers to induce symptoms of asthma. Conversely, WT splenocytes, Th2 cells and hematopoetic cells induced some symptoms of experimental asthma when transferred to VDR KO mice, but the severity was less than that seen in the WT controls. Interestingly, experimentally induced vitamin D deficiency failed to mirror the VDR KO phenotype suggesting there might be a difference between absence of the ligand and VDR deficiency. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced inflammation in the lungs of VDR KO mice was also less than in WT mice. Together the data suggest that vitamin D and the VDR are important regulators of inflammation in the lung and that in the absence of the VDR the lung environment, independent of immune cells, is less responsive to environmental challenges.

Keywords: asthma, vitamin D, mice, vitamin D receptor, lung

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that has increased in prevalence since the early 1980s especially in children. It has been suggested that there is a connection between vitamin D exposure early in life and the risk of developing asthma and allergies [1–3]. The active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; 1,25(OH)2D3) can modulate the immune response with beneficial effects on autoimmune diseases (reviewed in [4]). In models of experimental allergic asthma there is evidence that 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment can be beneficial [5, 6], has no effect [7] or is harmful [5, 7] when various markers of this disease are examined. More information on the role of vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2D3 in experimental asthma is required to resolve the controversy.

The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a member of the steroid thyroid superfamily of nuclear receptors. Ligand binding through the VDR mediates several biological activities, including regulation of T helper (Th) cell development and Th cytokine profile [8–10]. Located on chromosome 12q, genome wide screens have identified the VDR as a candidate gene associated with asthma [11, 12]. However, a recent study with asthmatic children found 13 single nucleotide polymorphisms in the VDR but could not find preferential transmission of VDR variants to children with asthma [13]. In addition, a second study has reported that the VDR gene is not associated with the pathogenesis of asthma or the expression of related allergic phenotypes such as eosinophilia and changes in total IgE [14]. The discrepancies are probably due to the different populations of patients studied and different outcomes measured.

The development of airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), mucus production and high serum IgE levels is characteristic of experimental models of asthma [15, 16]. CD4+ type 2 helper (Th2) cells play an important role in the production of IgE and the growth and differentiation of mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils [17, 18]. In asthmatics CD4+ T cells producing IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 have been identified in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). In model systems, adoptive transfer of antigen-specific lymphocytes, and antigen primed Th2 cells transferred experimental asthma to naïve animals including increased AHR and eosinophilia [19, 20]. In response to airborne allergens, the immune system of an asthmatic generates a Th2 biased immune response that causes lung airway inflammation.

VDR KO mice have been shown to be resistant to the development of experimental allergic asthma [7]. VDR KO mice induced to develop allergic asthma with ovalbumin (OVA) failed to develop airway inflammation, eosinophilia, or AHR, despite having high IgE concentrations and elevated Th2 cytokines (IL-13, and IL-5) in the periphery [7]. Interestingly, the IL-4 response was less in the VDR KO mice than the WT controls [7]. The experiments performed here used a series of adoptive transfer experiments followed by OVA stimulation to determine whether the failure of the VDR KO mice to develop experimental asthma resided in the immune system or the non-immune local lung environment. The data show that VDR KO splenocytes transfer experimental asthma to WT mice. Furthermore, asthma symptoms are induced in the VDR KO mice with transfer of WT immune cells but the severity of the disease is less than in the WT mice. The data point to a defect in the VDR KO lung micro-environment that results in the decreased infiltration of pathogenic lymphocytes, eosinophils, and the diminished induction of airway hyperresponsiveness.

Materials and Methods

Mice

VDR KO, OTII (OVA specific T cell receptor transgenic), and WT C57BL/6 mice were bred and maintained at the Pennsylvania State University (University Park, PA). For some experiments the mice were fed a diet devoid of vitamin D exactly as described [21]. Experimental procedures were approved by the Office of Research Protection’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennsylvania State University.

Immunization and challenge protocol

Donor mice were injected i.p. with OVA (0.1 mg Grade III; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in aluminum hydroxide (1 mg; Pierce, Rockford, IL) on d 0 and d 5. This is the standard priming protocol used previously to induce experimental allergic asthma in mice [7].

Culture of splenocytes for adoptive transfer

Splenocytes from donor mice (WT, and VDR KO) were resuspended at 2 × 106/ml in complete RPMI 1640 (Sigma) and cultured for 3 days at 37°C in the presence of 200 μg/ml OVA. For some experiments 20 U/ml IL-2 was added to the cultures. In additional experiments OTII (T cell receptor transgenic and OVA specific) splenocytes were cultured with 200 μg/ml OVA and Th2 driving conditions (500 U/ml IL-4 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and neutralizing IFN-γ antibodies- 1 ng/ml). The cultured splenocytes were layered onto Histopaque-1077 (Sigma) to isolate the live cells and cultured for an additional 4 days with 20 U/ml IL-2. After 7 days in culture the cells were washed and resuspended in sterile saline. 1 × 107 cells were injected (i.p.) into recipient mice. Recipients were challenged i.n. (3 days following the i.p. injection) with 20 μl and 40 μg OVA for 3 consecutive days.

Bone marrow transplant

In order to distinguish between donor derived and recipient cells B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ mice that carry the CD45.1 allele and C57BL/6 mice that carry CD45.2 were used. The recipient mice were treated with antibiotic (gentamicin 100 mg/ml, Butler, Dublin, OH) in acidified water (pH 2.5–3) for one week prior to the irradiation and the treatment continued for 10 days following transplantation. The recipient mice were treated with 950 cGy of lethal radiation using a cesium (Cs137) research irradiator to ablate the bone marrow (BM). The BM cells from 6–10 week-old donor mice were isolated and diluted in sterile saline to a final volume of 2 × 106 cells per 200μl and injected intravenously into the retro-orbital venous sinus of 6–10 week-old recipient mice. Reconstitution was determined 4–6 weeks following transplantation by isolating peripheral blood mononuclear cells and staining for the expression of the donor CD45.1 allele by FACS analysis. The recipient mice were then immunized to induce allergic asthma with OVA as described [7].

LPS induced lung inflammation

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL), and 10 μg LPS (from Escherichia coli O55:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in 20 μl of sterile saline or sterile saline alone and administered i.n. Mice were sacrificed at 3, 24 and 48 h post-exposure.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

The trachea was exposed through a midline incision and cannulated with a 24 gauge sterile needle (Small Parts Inc, Miami Lakes, FL). BAL was isolated by flushing 1 ml of sterile saline two times through the lung and collecting 2 ml of BAL per mouse. Total cell numbers and polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) were counted from each sample using an ADVIA 120 Hematology System (Bayer Diagnostic, Tarrytown, NY).

ELISA

Serum levels of total IgE and OVA-specific IgE were measured by ELISA (Pharmingen). The detection limit for total IgE level was 100 pg/ml. For analysis of OVA-specific IgE the plates were coated with OVA (20mg/ml) and levels were compared to values of control untreated mice.

OVA-specific cytokine secretion was determined from spleen cultures. Seventy-two hours after OVA (2 mg/ml) restimulation, supernatants from triplicate wells were removed. Cytokine levels were measured using ELISA OptEIA™ Mouse Sets (Pharmingen) for IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-γ. The IL-13 ELISA was from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). The detection limits were 12.5 pg/ml for IL-2, 31.25 pg/ml for IL-4, 62.5 pg/ml for IL-5, 40 pg/ml for IL-13 and 125 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Flow cytometric Analysis

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, splenocytes or BAL (106 cells) were incubated with antibodies for cell surface marker analysis. Antibodies used included PE conjugated anti-mouse CD4, IgM, CD69 Abs, and FITC conjugated anti-mouse CD45, CD45.1, CD8, B220, CD62L, CD11b Abs (BD Pharmingen). Stained cells were analyzed using a XL-MCL benchtop cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL).

Airway Hyperresponsiveness

Respiratory function was measured as described (Whole Body Plethysmograph; [7]) by determining the Penh values for each methacholine concentration. Results are reported as the relative Penh value for each methacholine concentration compared with baseline values. When exposing unanesthetized mice with obstructed airways to methacholine; some mice undergo considerable distress. In cases where mice show extreme difficulty breathing, the experiment is terminated. AHR was also measured by examining respiratory resistance using a mechanical ventilator and anesthetized mice as described [22]. In this method, mice are anesthetized and the full methacholine dose response can be evaluated. Results are reported as respiratory resistance with increasing concentrations of methacholine.

Histopathology

Lungs were fixed in formalin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at the Animal Diagnostic Laboratory (University Park, PA). The sections were scored blindly on a scale of 0–4 for inflammation and epithelial thickening exactly as described [7]. Inflammation: 0-no inflammation, 1-inflammatory cells present, 2-multiple loci of inflammation, 3-many inflammatory cells around bronchi, 4-inflammatory cells throughout the lung. Epithelial thickening: 0-normal, 1-some epithelial thickening, 2-multiple loci of thickened airway, 3-airways nearly completely obstructed by epithelial thickening, 4-normal structure not present. The scores for inflammation and epithelial thickening were added together and divided by 2 (range from 0–4). The results are presented as means ± SEs. LPS induced inflammation was scored using a different scale as reported by others [23]. Lungs were collected at 3, 24, and 48h post-LPS. Interstitial inflammation, intra-alveolar inflammation, edema and thrombi formation were each scored blindly on a scale of 0–3, with 0 - absent, 1 - mild, 2 - moderate, and 3 - severe and making the total inflammation score from 0–12.

Data Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired T-test and ANOVAs (StatView, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

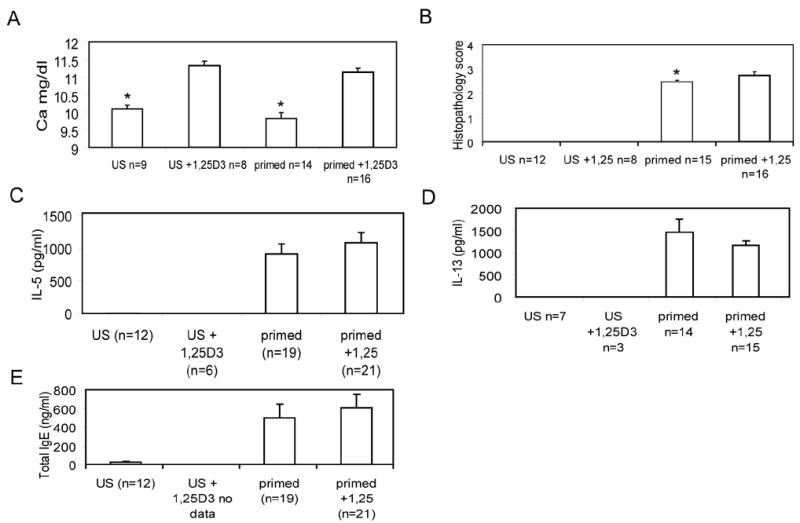

Vitamin D deficiency has mild effects on the severity of asthma

Vitamin D deficient mice were generated and either treated or not with 1,25(OH)2D3. The same method has been used to generate vitamin D deficient mice previously, and by 8–9 weeks of age the mice have no detectable 25(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 in circulation [24, 25]. Confirming the vitamin D deficiency there was no detectable levels of circulating 25(OH)2D3 and serum calcium values increased with the 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment. (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Mice were then immunized with OVA to develop allergic asthma. Examination of the lungs of these mice revealed that histopathology scores of vitamin D deficient mice were lower than 1,25(OH)2D3 fed vitamin D deficient mice ((P<0.05, Fig. 1B). IL-4, IL-13, total IgE and OVA specific IgE were similar from cells and serum of vitamin D deficient and 1,25(OH)2D3 treated mice (Fig. 1C–E). Except for a small change in histopathology severity the symptoms of experimental allergic asthma in vitamin D deficient mice were similar to the 1,25(OH)2D3 fed controls.

Figure 1. Development of experimental allergic asthma in vitamin D deficient and 1,25(OH)2D3 treated mice.

Vitamin D deficient mice were fed diets that either contained 1,25(OH)2D3 (1,25D3) or remained vitamin D deficient. Unsensitized (US) or OVA primed mice. A) Serum calcium values were significantly (*, P<0.05) elevated in 1,25D3 treated mice. B) Blinded histopathology scores were averaged for the different groups of mice as described in the methods. Vitamin D deficient mice developed less inflammation and epithelial hyperplasia than 1,25D3 treated vitamin D deficient mice (*, P<0.05). Levels of cytokine and IgE in vitamin D deficient or 1,25D3 treated mice with allergic asthma C) IL-5, and D) IL-13 production from re-stimulated splenocytes and E) total IgE levels in the serum.

Primed VDR KO splenocytes transfer allergic asthma to WT mice

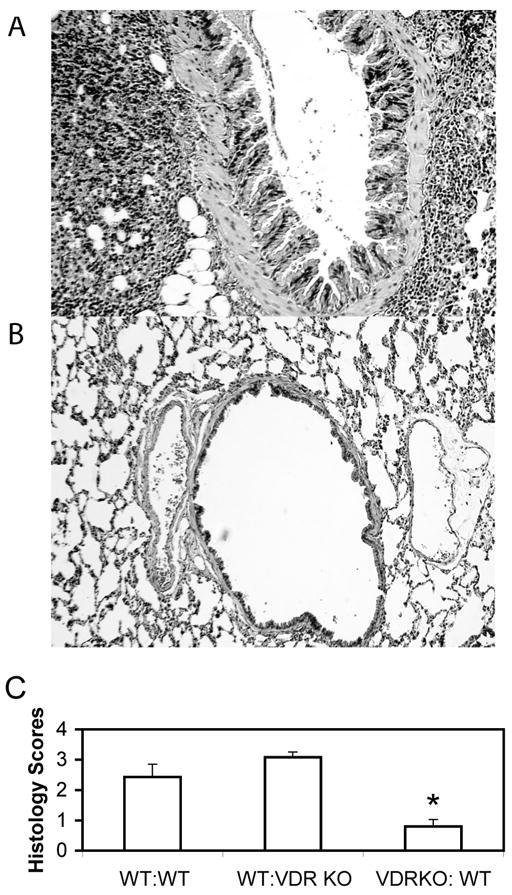

We have previously shown that mice lacking the VDR fail to develop allergic asthma [7]. To determine whether WT antigen specific splenocytes could transfer the disease into VDR KO mice, WT and VDR KO mice were primed with OVA and their splenocytes were removed and cultured in vitro with OVA for three days. Following culture the splenocytes were 60–70 % B cells, and the remainder were T cells (data not shown). Importantly there were not differences in the fraction of B and T cells between VDR KO and WT splenocytes when injected (data not shown). These cells were injected into naïve recipients and the recipients were then challenged i.n. with OVA over 3 days. WT mice that received WT splenocytes (WT:WT) showed infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes in both the perivascular and peribronchial space of the lung (data not shown, and Fig. 2C). Transfer of primed VDR KO cells into WT (WT:VDR KO) mice also resulted in inflammation of the lung that was phenotypically identical to that of WT recipients of WT cells (Fig. 2A and C). In contrast, VDR KO mice that received WT (VDR KO:WT) cells had little inflammation in the lung (Fig. 2B). As controls, VDR KO mice that received VDR KO cells (VDR KO:VDR KO), showed no disease development similar to unreconstituted VDR KO mice (data not shown). The lung histopathology scores from recipient VDR KO mice were significantly lower than in WT mice receiving WT cells or in WT mice receiving VDR KO cell (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Histopathology of the lungs following adoptive transfer of primed splenocytes.

Lungs were fixed, sectioned and stained with H&E for analysis of inflammation as described in the Material and Methods. A representative section from a WT mouse A) that received primed VDR KO cells (WT:VDR KO, score 3.5), a representative section from a VDR KO mouse B) that received primed WT cells (VDR KO:WT, score 0). C) Summary of the histopathology scores of 7–9 mice each. *Significantly different from the other two groups (P<0.05).

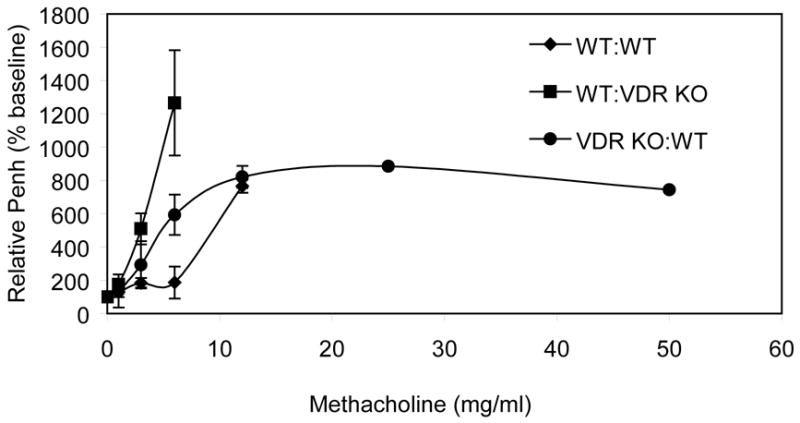

Consistent with the histopathology scores; WT mice that received primed splenocytes from either WT or VDR KO (WT:WT, WT:VDR KO) mice had elevated AHR responses at low doses of methacholine (Fig. 3). Note that complete methacholine dose curves could not be completed for WT:WT or WT: VDR KO recipients as the mice developed severe respiratory distress and difficulty breathing above 10 mg/ml methacholine and analysis had to be terminated. By contrast, VDR KO:WT recipients had no difficulty breathing at any of the tested methacholine concentrations. Consistent with the AHR and histopathology scores, VDR KO:WT recipients had lower IL-5 and IL-13 production (Table 1). The levels for IL-2 and IL-4 were below the detection level (data not shown). In contrast all groups produced high and equivalent amounts of IFN-γ (data not shown). As shown previously [7] VDR KO mice had elevated total IgE levels (Table 1).

Figure 3. AHR responses from WT and VDR KO recipients of either WT or VDR KO primed cells.

Penh values from WT recipients of primed WT cells (WT:WT) were significantly different than WT recipients of primed VDR KO cells (WT:VDR KO) at 3 and 6 mg/ml methacholine (p<0.05). WT:WT and WT:VDRKO mice could not be exposed to methacholine concentrations higher than 6 and 12 mg/ml respectively because the mice showed considerable difficulty breathing and distress. VDR KO:WT mice showed low responses to all methacholine concentrations tested.

Table 1.

Cytokine and IgE responses of WT and VDR KO recipients of primed splenocytes.

| Recipient | Donor | IL-5 (pg/ml) | IL-13 (pg/ml) | Total IgE (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | WT | 4420 ± 1067 | 8615 ± 1605 | 52 ± 15 |

| WT | VDR KO | 4710 ± 1244 | 8134 ± 2992 | 110 ± 49 |

| VDR KO | WT | 1437 ± 510* | 3096 ± 1110* | 2017 ± 147t |

IL-5 and IL-13 levels were significantly lower from VDR KO recipients compared to WT recipients.

IgE levels in the VDR KO recipient were significantly higher than the WT recipients.

These experiments were repeated using splenocytes from OVA primed WT mice with the addition of IL-2 during the in vitro OVA restimulation. The inclusion of IL-2 during in vitro restimulation resulted in a higher percentage of T cells 40–50% (data not shown). As described above, the IL-2 driven primed WT T cells transferred disease to naïve WT mice (AHR and lung inflammation) but the WT splenocytes did not induce AHR or lung inflammation when transferred to naïve VDR KO mice (data not shown).

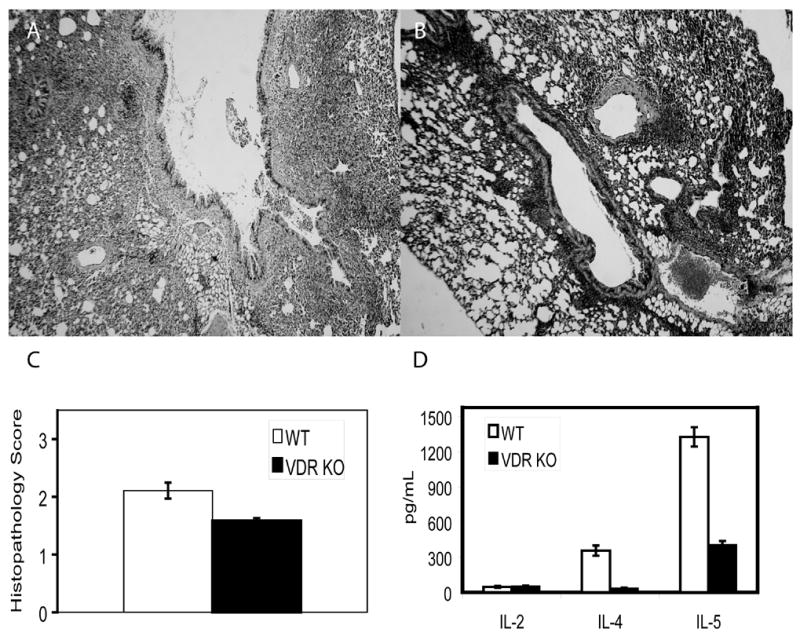

OT-II Th2 cells induced experimental asthma is less severe in VDR KO recipients

In order to increase the frequency of antigen specific and Th2 subtype cells; splenocytes from OVA specific transgenic mice (OT-II mice) were cultured with OVA under Th2 conditions for one week. The splenocytes were 90% T cells (by flow cytometry) and secreted high levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10 (data not shown). WT recipients of the transgenic T cells developed AHR (data not shown) and inflammation in the lung (Fig. 4A). OT-II transgenic T cells also induced inflammation in the lungs of VDR KO recipients (Fig. 4B); however, VDR KO recipients remained hyporesponsive to methacholine challenge (data not shown). While inflammation and epithelial hyperplasia were induced in VDR KO mice that received OT-II Th2 cells, the severity of the disease in the lung was less than that of the WT recipients of the same cells (Fig. 4B and 4C); with a P value of 0.078). Restimulated splenocytes from the VDR KO recipients secreted less IL-4 and IL-5 than WT recipients of the same OT-II cells (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. VDR KO recipients of OT-II Th2 cells exhibit reduced airway inflammation.

Representative lungs from A) WT (scored 3) and B) VDR KO (scored 2) recipients of OT-II Th2 cells. C) Blinded histopathology scores from 7 WT and 21 VDR KO recipients of OT-II Th2 cells. The results from the VDR KO mice were consistently lower than the WT recipients of the same cells, however there was a great deal of variability and the results did not reach significance (P=0.078). D) Cytokine response of splenocytes from WT and VDR KO recipients restimulated with OVA. IL-4 and IL-5 levels were significantly higher from WT than VDR KO mice (P<0.05).

Intranasal LPS induced inflammation is less severe in VDR KO mice

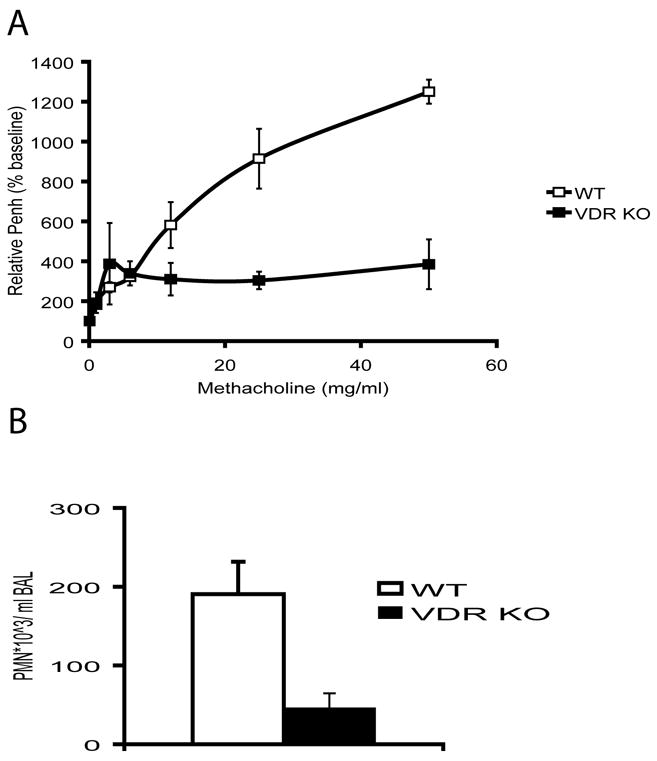

To determine whether the lungs of VDR KO mice were responsive to non-protein antigens such as bacterial LPS, VDR KO and WT mice were exposed i.n. to LPS or with sterile saline as a control. At 3, 24 and 48 h post LPS exposure lungs were harvested and analyzed. WT mice exhibited marked lung histological abnormalities, characterized by thickening of the alveolar septum, diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells and peribronchial inflammation. The extent of lung pathology was more severe in WT mice when compared with VDR KO mice (data not shown). Composite lung histopathology scores 3h, 24h, and 48h post-LPS were 4.7±0.8, 7.2±0.5 and 8.6±0.6 in WT mice and 3.1±0.3, 2.8±0.2, and 2.1±0.4 in VDR KO mice. The values from the WT mice were significantly different (P<0.05) at 24 and 48h post-LPS treatment when compared to the VDR KO values from the same time point. Consistent with the histopathology scores AHR responses were high in WT but not VDR KO mice exposed to LPS (Fig. 5A). The composition of BAL was also analyzed before and following LPS administration in WT and VDR KO mice. At time zero there were no significant differences in the total number or cell type in BAL fluid from WT and VDR KO mice. At 3h post-LPS administration a strong increase in the total cell numbers was observed. The BAL was characterized by increased numbers of PMN in the WT mice and significantly fewer PMN in the BAL from VDR KO mice (Fig. 5B). These data show that the VDR KO lung is resistant to inflammation induced by the bacterial polysaccharide LPS.

Figure 5. Decreased inflammation in VDR KO mice following LPS challenge.

WT (n=6) and VDR KO (n=6) mice were exposed i.n. with 10 μg of LPS. A) AHR responses of mice 24 hours post LPS exposure using the whole body plethysmograph. B) PMN influx in the BAL of WT and VDR KO mice 3 hours post LPS exposure.

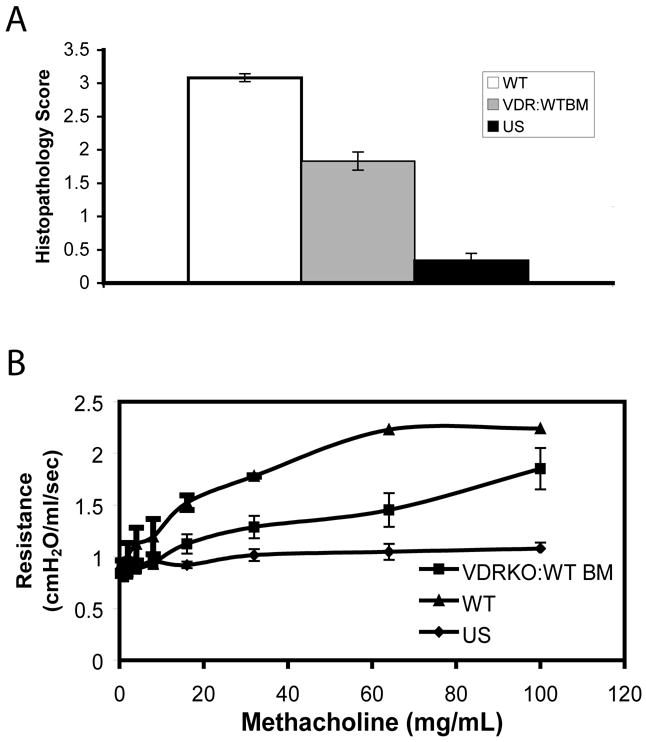

VDR KO recipients of WT BM show reduced asthma severity compared to WT mice

To determine if other hematopoietic cells could rescue development of allergic asthma in the VDR null mice, we performed BM transplantation experiments followed by induction of allergic asthma. VDR KO mice were sublethally irradiated and given WT BM transplants. The transplants were successful since analysis of the blood from the recipient mice showed that the lymphocytes were 88–97% of donor origin (CD45.1+). These mice were then immunized to induce experimental allergic asthma. Histopathology sections revealed that VDR KO recipients of WT BM (VDR KO:WT BM) developed inflammation and epithelial hyperplasia in the lungs that was greater than the non-transplanted VDR KO mice following induction of allergic asthma (Fig. 6A). However, the severity of the histopathology scores in VDR KO:WT BM mice were less (although not significant P=0.084) than WT mice (Fig. 6A). Importantly, the VDRKO:WT BM mice had significantly higher histopathology scores than untransplanted and allergic asthma induced VDR KO mice (Fig. 6A, P<0.05). Other markers of asthma severity (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-5) were not different between WT and VDR KO:WT BM recipients (data not shown).

Figure 6. WT bone marrow reconstitution of VDR KO mice induces AHR and lung inflammation that is less than the WT response.

Airway inflammation and AHR in WT, VDR KO and VDRKO:WT BM recipients induced to develop experimental asthma. A) Histopathology scores of lungs from WT, VDR KO and VDRKO:WT BM mice induced to develop allergic asthma (n=4–6). B) AHR responses (respiratory resistance) of mice treated as in (A). Unsensitized VDR KO and WT (UN) mice did not respond to any dose of methacholine. VDR KO:WT BM transplanted mice had elevated AHR responses to increasing doses of methacholine. VDRKO:WT BM AHR values were lower than the WT response at 16 mg/ml (P=0.083), 32mg/ml (P=0.733), 64 mg/ml (P=0.065) and 100 mg/ml (P=0.117) methacholine.

We measured lung resistance as a measure of AHR in the VDR KO:WT BM mice that were induced to develop asthma using mechanical ventilation (Fig. 6B). While the VDR KO:WT BM mice showed elevated AHR responses, this was lower than that seen in similarly treated WT mice (Fig. 6B). In addition, unsensitized VDR KO (Fig. 6B) or WT (data not shown) mice did not respond at any dose of methacholine.

Discussion

It has previously been shown that the VDR KO mouse is resistant to the development of experimental allergic asthma [7]. Interestingly, vitamin D deficiency did not mimic VDR deficiency and the vitamin D deficient mice developed experimental asthma although the severity of the inflammation and hyperplasia in the lungs of these mice was somewhat less than the scores from mice supplemented with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 1). There are a number of possible explanations for the difference in allergic asthma development between VDR and ligand deficient mice. The first possibility is that vitamin D deficiency is incomplete since mice are nocturnal animals and small amounts of vitamin D can be produced from white light or supplied via the milk of the dams that are not vitamin D deficient. If vitamin D depletion was more complete it is possible that the development of experimental allergic asthma in the vitamin D deficient and VDR KO mice would be similar. Conversely, it’s possible that the VDR has non-ligand dependent effects on the development of experimental asthma and in the absence of the receptor this mode of regulation is absent. Lastly, it is possible (although unlikely) that the effects of VDR deficiency on experimental asthma are a result of the high levels of endogenous 1,25(OH)2D3 that circulate in the VDR KO mouse and the 1,25(OH)2D3 acts in a non-VDR dependent fashion. There is at least one other example of a disease model where vitamin D and VDR deficiency do not result in the same phenotype. It has been shown in the multiple sclerosis model (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis) that vitamin D deficiency accelerates and VDR deficiency prevents symptom development [24, 26]. Conversely, in models of inflammatory bowel disease, disease development is more severe in vitamin D deficiency and VDR deficiency [25, 27].

The failure of the VDR KO mouse to develop experimental asthma is not due to a failure of immune cells to be primed and activated. The data show that OVA primed VDR KO splenocytes function in a similar manner to WT splenocytes when transferred to WT mice for experimental asthma induction (Fig. 2 and 3). Therefore the ability of T and B cells to be primed and activated in the VDR KO host is adequate for the development of pathogenic immune cells (Fig. 2 and 3). The data also suggest that VDR KO T cells are able to home to the WT lung where they accumulate and induce AHR and immunopathology.

However, the VDR KO mouse is resistant to the induction of lung inflammation; even though pathogenic T cells are primed and activated. WT primed splenocytes were unable to transfer experimental asthma to VDR KO mice (Fig. 2 and 3). Furthermore, when transferred to VDR KO mice, WT OT-II transgenic Th2 cells caused disease in the VDR KO host however the magnitude of the response was less than that seen in WT recipients. Similarly, while hematopoetic reconstitution of the VDR KO mice rendered the mice more susceptible to induction of experimental allergic asthma, the reconstituted VDR KO mice still had less severe airway inflammation than WT mice. Although, pathogenic immune cells and T cells are present and primed in the VDR KO host they must fail to reach the lung and therefore experimental asthma is less. The data point to a failure of the lung microenvironment to attract the pathogenic cells to the lungs.

The VDR KO mice were also hypo-responsive when challenged via the airways with bacterial LPS and the response was significantly less than the WT (Fig. 5) controls. The response to LPS is controlled by signaling through pattern recognition receptors like the toll receptors (TLR, TLR4 for LPS) present on the lung epithelium and innate immune cells. The decreased response of the VDR KO mice to LPS suggests that the VDR may be important in regulating TLR signaling. Vitamin D has been shown to regulate TLR mediated events in both macrophage and dendritic cells (DC). TLR mediated macrophage production of IL-12, and TNF-α production can be inhibited by 1,25(OH)2D3 [28, 29] and LPS stimulation of macrophages upregulated VDR expression [30]. Conversely, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited expression of TLR-4 which could decrease LPS responsiveness of these cells [31]. Clearly, 1,25(OH)2D3, the VDR and TLRs are important and interdependent regulators of the early innate immune response. The decreased response of the VDR KO mice to i.n. LPS suggests that the immediate innate response in the lung is impaired and points to an important role of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D3 and the VDR in regulation of these pathways in the lung.

The data presented here support an important role of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D3 and the VDR in the lung response to inflammatory signals, specifically, the innate immune response. Significant inflammation in the VDR KO lung is not rescued by transplantation of WT immune splenocytes, T cells or hematopoetic cells pointing to decreased responsiveness of the lung microenvironment in the absence of the VDR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Anja Wittke, Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Andrew Chang, Integrated Biosciences Graduate Program, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Monica Froicu, Pathobiology Graduate Program, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Omid F. Harandi, Genetics Graduate Program, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

Veronika Weaver, Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Avery August, Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Robert F. Paulson, Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

Margherita T. Cantorna, Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

References

- 1.Hypponen E, Sovio U, Wjst M, Patel S, Pekkanen J, Hartikainen AL, Jarvelinb MR. Infant vitamin d supplementation and allergic conditions in adulthood: northern Finland birth cohort 1966. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1037:84–95. doi: 10.1196/annals.1337.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wjst M, Dold S. Genes, factor X, and allergens: what causes allergic diseases? Allergy. 1999;54:757–759. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milner JD, Stein DM, McCarter R, Moon RY. Early infant multivitamin supplementation is associated with increased risk for food allergy and asthma. Pediatrics. 2004;114:27–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matheu V, Back O, Mondoc E, Issazadeh-Navikas S. Dual effects of vitamin D-induced alteration of TH1/TH2 cytokine expression: enhancing IgE production and decreasing airway eosinophilia in murine allergic airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:585–592. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topilski I, Flaishon L, Naveh Y, Harmelin A, Levo Y, Shachar I. The anti-inflammatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on Th2 cells in vivo are due in part to the control of integrin-mediated T lymphocyte homing. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1068–1076. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittke A, Weaver V, Mahon BD, August A, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D receptor-deficient mice fail to develop experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2004;173:3432–3436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonstra A, Barrat FJ, Crain C, Heath VL, Savelkoul HF, O’Garra A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4974–4980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahon BD, Wittke A, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. The targets of vitamin D depend on the differentiation and activation status of CD4 positive T cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:922–932. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overbergh L, Decallonne B, Waer M, Rutgeerts O, Valckx D, Casteels KM, Laureys J, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces an autoantigen-specific T-helper 1/T-helper 2 immune shift in NOD mice immunized with GAD65 (p524–543) Diabetes. 2000;49:1301–1307. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon AH, Laprise C, Lemire M, Montpetit A, Sinnett D, Schurr E, Hudson TJ. Association of vitamin D receptor genetic variants with susceptibility to asthma and atopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:967–973. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-412OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raby BA, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, Lake S, Lange C, Wjst M, Weiss ST. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with childhood and adult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1057–1065. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-447OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wjst M. Variants in the vitamin D receptor gene and asthma. BMC Genet. 2005;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vollmert C, Illig T, Altmuller J, Klugbauer S, Loesgen S, Dumitrescu L, Wjst M. Single nucleotide polymorphism screening and association analysis--exclusion of integrin beta 7 and vitamin D receptor (chromosome 12q) as candidate genes for asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1841–1850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romagnani S. Cytokines and chemoattractants in allergic inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:881–885. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamelmann E, Tadeda K, Oshiba A, Gelfand EW. Role of IgE in the development of allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness--a murine model. Allergy. 1999;54:297–305. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Ambrosio D, Mariani M, Panina-Bordignon P, Sinigaglia F. Chemokines and their receptors guiding T lymphocyte recruitment in lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1266–1275. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2103011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrick CA, Bottomly K. To respond or not to respond: T cells in allergic asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nri1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise JT, Baginski TJ, Mobley JL. An adoptive transfer model of allergic lung inflammation in mice is mediated by CD4+CD62LlowCD25+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:5592–5600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan SP, Koskinen A, Matthaei KI, Young IG, Foster PS. Interleukin-5-producing CD4+ T cells play a pivotal role in aeroallergen-induced eosinophilia, bronchial hyperreactivity, and lung damage in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:210–218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.mar-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C, Mahon BD. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J Nutr. 2000;130:2648–2652. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewart S, Levitt R, Mitzner W. Respiratory system mechanics in mice measured by end-inflation occlusion. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:560–566. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.2.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knapp S, Florquin S, Golenbock DT, van der Poll T. Pulmonary lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein inhibits the LPS-induced lung inflammation in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;176:3189–3195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reversibly blocks the progression of relapsing encephalomyelitis, a model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7861–7864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C, Mahon BD. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J Nutr. 2000;130:2648–2652. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meehan TF, DeLuca HF. The vitamin D receptor is necessary for 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) to suppress experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;408:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Froicu M, Weaver V, Wynn TA, McDowell MA, Welsh JE, Cantorna MT. A crucial role for the vitamin D receptor in experimental inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2386–2392. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen ML, Douvdevani A, Chaimovitz C, Shany S. Regulation of TNF-alpha by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human macrophages from CAPD patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59:69–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penna G, Adorini L. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Schauber J, Wu K, Meinken C, Kamen DL, Wagner M, Bals R, Steinmeyer A, Zugel U, Gallo RL, Eisenberg D, Hewison M, Hollis BW, Adams JS, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadeghi K, Wessner B, Laggner U, Ploder M, Tamandl D, Friedl J, Zugel U, Steinmeyer A, Pollak A, Roth E, Boltz-Nitulescu G, Spittler A. Vitamin D3 down-regulates monocyte TLR expression and triggers hyporesponsiveness to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:361–370. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]