Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of the study was to establish a procedure for early diagnosis and treatment of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI).

Background:

NOMI has a high mortality rate, and early diagnosis and treatment are important for improving survival in patients with this condition.

Methods:

The subjects were 22 patients treated at our hospital over 13 years. Diagnostic criteria for NOMI were established based on the first 13 cases. In the 9 more recent cases, we performed abdominal contrast multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) upon suspicion of NOMI based on these criteria. Imaging allowed definite diagnosis of NOMI, and continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration was initiated immediately after diagnosis (dose, 0.01–0.03 μg/kg per min; mean administration period, 4.8 days).

Results:

Nine of the first 13 patients died of multiple organ failure associated with multiple intestinal necrosis. These cases suggested that NOMI may develop when 3 of the following 4 criteria are met after cardiovascular surgery or maintenance dialysis in elderly patients: symptoms of the ileus develop slowly from abdominal symptoms, such as an unpleasant abdominal feeling or pain; a requirement for catecholamine treatment; an episode of hypotension; and slow elevation of the serum transaminase level. In the 9 recent cases, definite diagnosis was made from spasm of the principal arteries in arterial volume rendering and curved planar reformation MDCT images. Early treatment with PGE1 prevented acute-stage NOMI in 8 of the 9 cases.

Conclusions:

Early diagnosis of NOMI is possible using the above criteria and MDCT, and initiation of PGE1 treatment may increase survival in patients with NOMI.

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) has a high mortality rate, and early diagnosis and treatment are important for improving survival. Upon suspicion of NOMI, based on criteria reported here, diagnosis using abdominal contrast multidetector row computed tomography and immediate initiation of continuous intravenous high-dose prostaglandin E1 administration may increase survival in NOMI patients.

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) is an acute mesenteric circulatory disorder that, in contrast to mesenteric arterial occlusion induced by blockage of blood flow by emboli and thrombi, is not caused by organic occlusion of blood vessels. Early diagnosis and early treatment are very important in NOMI, but the early symptoms and characteristics are unclear; and in many cases, the disease has advanced to an irreversible stage before a definite diagnosis is made. Our experience with diagnosis and treatment of NOMI has led us to establish new diagnostic criteria, and we now perform abdominal contrast multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) for suspected NOMI. Abnormalities in 3-dimensional images of the principal arteries enable early definite diagnosis, and we have achieved good outcomes with subsequent early treatment with continuous intravenous high-dose prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).

METHODS

The cases of 22 NOMI patients treated at our hospital in the last 13 years were investigated. Diagnostic criteria for suspected NOMI were established based on the first 13 of these cases, and abdominal contrast MDCT, rather than abdominal angiography, was performed in the 9 most recent cases, following application of the new diagnostic criteria. A definite diagnosis of NOMI was made from characteristic abnormal findings in VR and CPR images, and continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration was immediately initiated.

The acquisition conditions using a 16-row MDCT (Aquilion 16, Toshiba Co.) were as follows: tube voltage, 120 to 135 kVp: tube current, 350 to 400 mA; scan time, 0.5 seconds/rotation; slice thickness, 1 mm; and helical pitch, 15. The volume of the contrast medium concentration was 300 or 320 mg/ml, the injection volume was set equal to the body weight × 2 to 2.5 ml, and the infusion rate was 3.5 to 4.0 mL/s. Image editing software was used on an Aquarius Workstation (Terarecon Co.).

RESULTS

Cases Untreated With Continuous Intravenous PGE1

Of the 22 NOMI cases at our hospital in the last 13 years, 13 were not treated with PGE1 at onset; the details of these cases are shown in Table 1. The patients comprised 10 males and 3 females, and the mean age at onset was 71.0 years. NOMI occurred frequently after cardiovascular surgery: 5 cases after surgery for thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms, 2 cases after valve replacement, and 1 case after coronary arterial bypass. Three cases occurred after maintenance dialysis. Four patients had an episode of transient hypotension before onset, and 9 were under treatment with catecholamines such as dopamine hydrochloride. Early abdominal symptoms were noted in all cases, but no patients reported severe pain. Identification of the onset time was difficult; however, the disease began with mild abdominal pain or an unpleasant feeling in the abdomen, and these symptoms gradually worsened. Finally, typical symptoms of intestinal obstruction, such as sensation of an enlarged abdomen, and vomiting developed.

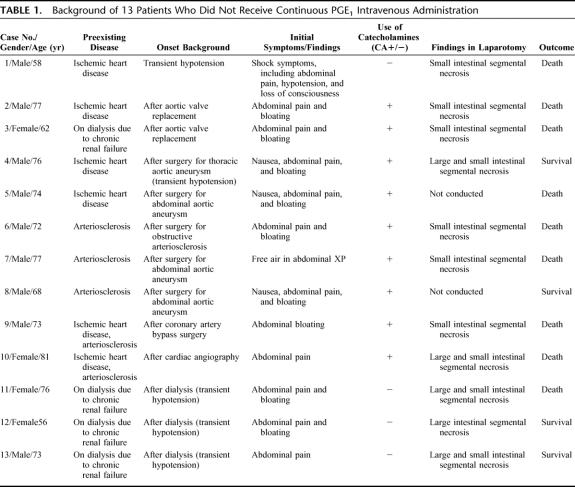

TABLE 1. Background of 13 Patients Who Did Not Receive Continuous PGE1 Intravenous Administration

Elevation of glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) corresponding to the degree of intestinal necrosis was noted in all cases, but no other characteristic blood findings were noted. Diagnosis of NOMI by abdominal angiography was possible in only 1 of the 13 cases (case 6). The disease was diagnosed comprehensively based on abdominal CT images (planar slices on conventional CT) and laboratory tests in 4 cases (cases 4, 5, 8, and 9), and final diagnosis was made by laparotomy and histopathological examination in the remaining cases.

One case was treated with PGE1 administration through an indwelled arterial catheter (case 6) and one case resolved with conservative treatment (case 8). In the other 11 cases, excision of the necrotic intestine or enterostomy was performed, but 9 of these patients died, with the cause of death being multiple organ failure associated with massive intestinal necrosis. Excision of the necrotic intestine was initiated 24 to 72 hours after onset, with PGE1 administration also initiated in cases 6 during this time.

Based on our first 13 cases, we concluded that it is likely that NOMI has developed in elderly patients when the following items are found after cardiovascular surgery or maintenance dialysis: 1) symptoms of the ileus that slowly appear after initial abdominal symptoms, such as an unpleasant feeling in the abdomen and abdominal pain; 2) a requirement for catecholamine treatment; 3) an episode of hypotension; and 4) slow elevation of the transaminase level.

Cases Treated With Continuous Intravenous PGE1

After the initial 13 cases, subsequent patients meeting 3 of the 4 criteria above were suspected to have NOMI. Nine such cases arose, and continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration was initiated immediately before completion of all diagnostic examinations (Table 2). The patients comprised 6 males and 3 females, and the disease occurred after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in 4 cases, after valve replacement in 2 cases, and after maintenance dialysis in 1 case. The mean age was 70.2 years. Various early abdominal symptoms were noted, including abdominal pain and an unpleasant feeling in the abdomen. Two of the patients had transient hypotension before onset, 6 were receiving catecholamines, and the transaminase level was significantly elevated in all 9 patients.

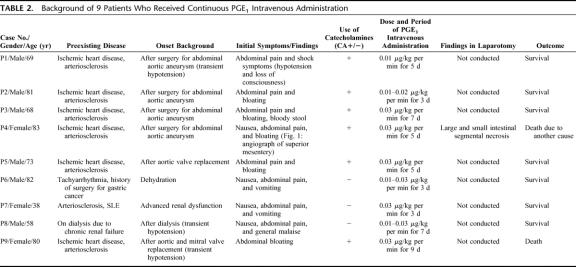

TABLE 2. Background of 9 Patients Who Received Continuous PGE1 Intravenous Administration

PGE1 was administered intravenously at a dose of 0.01 to 0.03 μg/kg per min, and the mean duration of administration was 4.8 days after onset. Abdominal contrast MDCT was performed in all 9 cases, rather than abdominal angiography. In 7 cases, enhancement of principal arteries could be traced to the periphery close to the marginal arteries in CT slices, and the staining intensity varied in the intestinal wall in the same slice (showing a difference between regions of the intestinal wall with good and poor blood flow). This finding may be useful as supplemental information in diagnosis of NOMI. In the other 2 cases (cases P6 and P8), sharp spasm-induced narrowing was noted at a site 5 cm peripheral from the root of the superior mesenteric artery in VR and CPR MDCT images, and definite diagnosis of NOMI was achieved by acquisition of an image showing retention of blood flow up to the marginal arteries of the intestine (the details of case P6 are described below).

Of the 9 recent cases, acute-stage NOMI resolved in 1 patient with recovery of oral ingestion, but then the patient complicated with infectious disease and died on the 65th day after onset of NOMI. In another case, PGE1 was not effective, NOMI progressed, and the patient died of multiple intestinal necrosis and sepsis. However, the other 7 PGE1-treated patients recovered smoothly and were discharged.

Case in Which Resolution by PEG1 Was Monitored by MDCT

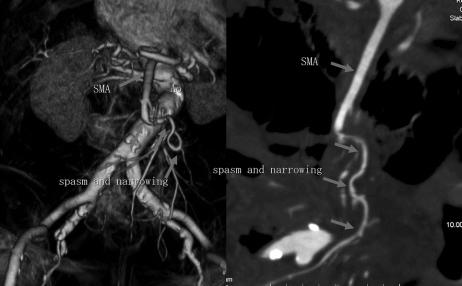

An 82-year-old man (case P6) with a medical history of hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and tachyarrhythmia (for which he had not received regular medication) was admitted for upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that had started on the previous day. Blood pressure on admission was 125/65 (usually 160/100) with a slight fever at 37.0°C. The abdomen was enlarged and moderate tenderness was noted. Niveau formation was found on plain abdominal XP images. In abdominal contrast MDCT slices, a large volume of ascites and poor enhancement over the entire small intestinal wall were noted, despite retention of the superior mesenteric arterial blood flow to the periphery. In arterial VR and CPR images in abdominal MDCT, spasm-induced narrowing was noted at a site about 5 cm peripheral from the root of the superior mesenteric artery, but the blood flow to the intestinal marginal arteries was maintained (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Images on admission for case P6: (left) VR image from MDCT; and (right) CPR image. Spasm led to narrowing of the superior mesenteric artery in a peripheral area 5 cm from the root of the artery; however, blood flow to the intestinal marginal artery was observed.

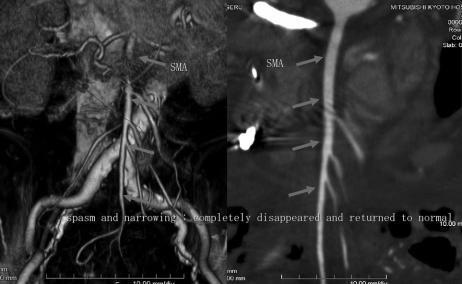

After admission, NOMI due to vomiting-induced dehydration was diagnosed, and continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration was immediately initiated (the dose was escalated to a final dose of 100 μg/h). Spasm and narrowing of the superior mesenteric artery were improved in abdominal MDCT images on the following day. After 5 days, ascites was reduced, contrast enhancement of the small intestinal wall had improved, and spasm and narrowing of the superior mesenteric artery were resolved in MDCT (Fig. 2). Intravenous PGE1 administration was stopped at this point, since the disease symptoms had resolved, and the patient was discharged on the 19th day of hospitalization.

FIGURE 2. Images on hospital day 5 for case P6: (left) VR image from MDCT; and (right) CPR image. Spasm and narrowing of the superior mesenteric artery had completely disappeared and the artery had returned to normal.

DISCUSSION

NOMI accounts for more than 10% to 20% of cases of acute mesenteric circulatory disorders and leads to extensive irreversible intestinal necrosis for which the prognosis is very poor, despite the absence of organic obstruction in the principal arteries. Ende et al described what are considered to be the first reported cases of NOMI in 3 patients with heart failure-associated low output in 1958.1 Subsequently, many more cases have been described, mainly in Europe and America, with a mortality rate of 70% to 90% that has not changed over time; furthermore, the cause of death has been related to NOMI in 9% of fatal dialysis cases.2 Regarding pathogenesis, intestinal vasospasm due to persistent low perfusion is thought to cause ischemic disorder due to decreased cardiac output and blood pressure.3,4 Digitalis preparations and catecholamines often induce vasospasm, and associations of NOMI with activation of the renin-angiotensin system and vasopressin secretion from the pituitary gland have also been reported.5

Most NOMI patients are elderly, and the disease is more likely to occur in ICU and CCU patients after cardiovascular surgery and dialysis. NOMI can be induced by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and ileus symptoms, but the characteristic early symptoms and laboratory test results are unclear. Compared with mesenteric thrombosis, NOMI also frequently occurs postoperatively in patients with unclear consciousness and severe disease. Early diagnosis is difficult, and during the diagnostic process the disease slowly advances to an irreversible state with extensive intestinal necrosis. Detection of subjective symptoms is difficult in cases that develop after surgery because the effects of general and epidural anesthesia may remain and the disease may develop and advance unnoticed. Laparotomic characteristics are inevitably present in patients who underwent laparotomy, but mesenteric blood flow may be retained, even in marginal arteries reaching the lesions, despite extensive necrotization throughout the intestine (noncontinuous segmental necrosis). This is a marked distinguishing feature from mesenteric thrombosis, in which the mesentery and intestine are necrotized from the site of the thrombus, forming a sphenoidal necrotic area in the region served by the artery (continuous necrosis).

The first-line therapy upon suspicion of NOMI has been abdominal angiography and continuous administration of vasodilators such as papaverine, PGE1, and nitroglycerine into the mesenteric artery. Boley et al reported narrowing of many branches of the superior mesenteric artery (the so-called “string of sausages” sign: alternate dilation and stenosis of the superior mesenteric arterial branches), spasm of the intestinal marginal artery, and poor contrast enhancement of veins in the muscular layer as features of vasospasm associated with NOMI.6 However, NOMI often occurs in patients with poor or unstable systemic conditions, and angiography may not be possible due to its complexity and invasiveness, thereby missing the opportunity for resolution in many cases. Based on previous reports and on our experience, angiography is rarely useful for early diagnosis. For definite diagnosis, observation of the absence of organic obstruction of blood vessels distributed in the necrotic intestinal region and segmented discontinuous intestinal ischemic changes and necrosis on laparotomy, and histopathologic detection of hemorrhagic and necrotic changes are required.7,8 However, our experience suggests that in many cases the time required for definite diagnosis may compromise the chance for survival.

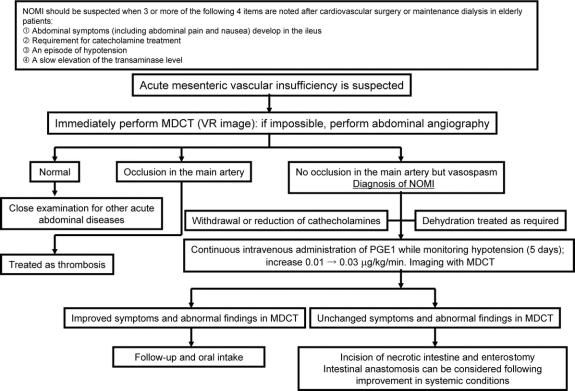

Based on our observations in NOMI cases, we have established original diagnostic criteria for suspected NOMI and we now perform MDCT instead of angiography upon suspicion of NOMI. Characteristic abnormal arterial findings in MDCT enable a rapid definite diagnosis. Data collected by multirow detectors can be reconstructed rapidly to give 3-dimensional images that provide vascular information comparable to that obtained in angiography. Before introduction of MDCT, the principal arteries could be traced to a peripheral level close to the marginal arteries using conventional contrast CT. However, the staining intensity in these images varied due to differences between regions with good and poor blood flow in the intestinal wall, and this information could only be used to supplement other observations in diagnosis of NOMI. In contrast, performance of abdominal contrast MDCT upon suspicion of NOMI allows definite diagnosis and permits subsequent early initiation of therapy and monitoring of disease resolution (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. NOMI diagnosis and treatment plan in our hospital.

Immediate initiation of continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration at the time of suspected onset of NOMI achieved good outcomes in 8 of our 9 recent cases. Laparotomy was unnecessary in 7 of the 8 successfully treated cases (excluding cases P4); thus, a definite diagnosis by laparotomy and histopathologic examination was not made; therefore, it cannot be formally ruled out that the disease was something other than NOMI, based on previous diagnostic criteria. However, the time required for definite diagnosis based on laparotomic findings and pathologic examination of excised specimens may compromise successful treatment. Marked increases in GOT, GPT, LDH, and creatine phosphokinase (CPK), and advanced metabolic acidosis due to intestinal ischemia indicate progression of intestinal necrosis, and the chance of survival is reduced.

The main goal of current therapy for NOMI is reduction of spasm and improved perfusion of the mesenteric artery using vasodilators, and the role of surgery is limited to diagnostic laparotomy and excision of irreversibly necrotized intestine. PGE1 is a potent vascular smooth-muscle relaxant due to its peripheral vasodilatory activity, inhibition of platelet aggregation, effect on reduction of erythrocyte deformation, and inhibition of production of reactive oxygen. It has been used as a drug for vascular obstructive lesions in the extremities, such as arteriosclerosis obliterans and thromboangitis, and is known to improve blood flow in the digestive tract. Elimination of PGE1 from blood is biphasic, with half-lives of 0.2 minutes (α phase) and 8.2 minutes (β phase),9 and PGE1 in blood is mostly metabolized rapidly in the liver. Thus, a continuous effect cannot be expected with intermittent administration, and continuous administration through a catheter inserted into the principal artery is more effective.

PGE1 administered into blood is 65% metabolized in the liver, with the remaining 35% being circulated systemically,10 and intravenous administration at a constant rate results in maintenance of a constant blood concentration.9 Theoretically, continuous intravenous administration at a high dose may exhibit an effect similar to that of continuous local arterial administration; therefore, we immediately initiated continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration upon suspicion of NOMI and achieved good outcomes using this approach. Although no standard dose for continuous mesenteric arterial administration has been established, we set the dose at 0.01 to 0.03 μg/kg per min, which is lower than that used for treatment of abnormally high blood pressure (0.05–0.1 μg/kg per min). PGE1 was continuously administered for a maximum of 5 days (until abdominal symptoms had improved) within a dose range that did not influence the systemic circulatory dynamics, thus avoiding heart failure and shock. The target period of PGE1 administration was set to 5 days because a tendency for changes in the condition became apparent within 5 days after onset in most early NOMI cases we encountered, regardless of the treatment method and improvement or aggravation of the condition. The PGE1 dose should be carefully set when NOMI is accompanied by hemorrhage of the digestive tract, or when mesenteric thrombosis is suspected and treated with concomitant thrombolytic agents, since PGE1 has potent inhibitory action on platelet aggregation and shows a tendency to enhance hemorrhage.

Cases of NOMI are increasingly common due to the aging of society and an increase in the dialysis population, but the disease concept has not been fully established. Moreover, NOMI is not recognized easily and is difficult to diagnose; therefore, many NOMI patients may not have been diagnosed correctly and consequently may have died without receiving adequate treatment. The time of treatment initiation after onset determines the prognosis of this disease, but the current approach using diagnostic and therapeutic abdominal angiography and subsequent continuous mesenteric arterial administration of vasodilators is unlikely to increase the survival rate. In contrast, it is important to identify possible NOMI based on the background at the time of disease onset, since the disease lacks characteristic symptoms and is fatal in the advanced stage. As we have shown, early diagnosis in suspected cases can be made using abdominal contrast MDCT and reconstruction of 3-dimensional images of the principal arteries, and early initiation of continuous intravenous high-dose PGE1 administration may increase survival of NOMI patients.

Footnotes

Reprints: Akira Mitsuyoshi, MD, Department of Surgery, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital, 1 Katsura Gosho-machi, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto, 615-8087, Japan. E-mail: akiram7700@yahoo.co.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ende N. Infarction of the bowel in cardiac failure. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:879–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han SY, Kwon XJ, Shin JH, et al. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia in a patient on maintenance hemodialysis. Korean J Intern Med. 2000;15:81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassiounty HS. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey RW, Bulkley GB, Hamilton SR, et al. Protection of the small intestine from nonocclusive mesenteric ischemic injury due to cardiogenic shock. Am J Surg. 1987;153:108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lock G, Scholmerich J. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boley SJ, Sprayregan S, Siegelman SS, et al. Initial results from an aggressive roentgenological and surgical approach to acute mesenteric ischemia. Surgery. 1977;82:848–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heer FW, Silen W, French SW. Intestinal gangrene without apparent vascular occlusion. Am J Surg. 1965;110:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fogarty JT, Fletcher SW. Genesis to nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Am J Surg. 1966;111:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawello W, Schweer H, Muller R, et al. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of prostaglandin E1 administered by intravenous infusion in human subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golub M, Zia P, Matsuno M, et al. Metabolism of prostaglandins A1 and E1 in man. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:1404–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]