Abstract

Strategies for identifying urban youth with asthma have not been described for high school settings. African-American high school students are rarely included in asthma studies, despite a high risk of asthma mortality when compared to other age and race groups. Identification and follow-up of children with uncontrolled respiratory symptoms are necessary to reduce the burden of asthma morbidity and mortality, especially in underserved areas. We describe a process used to identify high school students who could benefit from intervention based on self-report of asthma and/or respiratory symptoms, and the costs associated with symptom-identification. Letters announcing a survey were mailed to parents of 9th–11th graders by an authorized vendor managing student data for the school district. Scan sheets with student identifiers were distributed to English teachers at participating schools who administered the survey during a scheduled class. Forms were completed by 5,967 of the 7,446 students assigned an English class (80% response). Although prevalence of lifetime asthma was 15.8%, about 11% of students met program criteria for enrollment through report of an asthma diagnosis and recent symptoms, medication use, or health care utilization. Another 9.2% met criteria by reported symptoms only. Cost of symptom-identification was $5.23/student or $32.29/program-eligible student. There is a need for school-based asthma programs targeting urban adolescents, and program initiation will likely require identification of students with uncontrolled symptoms. The approach described was successfully implemented with a relatively high response rate. Itemized expenses are presented to facilitate modifications to reduce costs. This information may benefit providers, researchers, or administrators targeting similar populations.

Keywords: Adolescent, African-American, Asthma, Screening, Urban

Introduction

Despite the debate on the necessity and feasibility of screening for asthma in schools, there is a general consensus that the process of identifying and following-up children with uncontrolled respiratory symptoms deserves attention.1 This is especially true for youth in underserved communities and is crucial to the reduction of racial disparities in asthma-related morbidity and mortality.2

The process of “symptom-identification” is used to identify persons with symptoms of asthma, usually through the use of surveys. This process differs from case-detection, which is the identification of symptomatic students with no diagnosis. In symptom-identification, students with and without a diagnosis are targeted. Symptom-identification does not use existing data (e.g., school health records), and so differs from case-identification, which is the identification of students with asthma using existing information (e.g., school records). Finally, symptom-identification differs from screening, which is the identification of apparently well individuals without symptoms but who have pre-clinical disease.3 In contrast, symptom-identification is used to find students with asthma symptoms who would be eligible for subsequent referral and/or intervention, e.g., enrollment in a research program or an existing school-based asthma program.

Various symptom-identification methods for asthma have been described for elementary and middle schools, but few papers discuss methods for identifying youth with asthma symptoms in the high school setting.4–7 Urban adolescents aged 15–18 years are rarely included in asthma studies, although asthma-related mortality for this group is high relative to other age and race groups.8 Symptom-identification could be a key step in the process of understanding barriers to effective treatment and management of asthma in urban high school students.

We describe a symptom-identification protocol used to identify urban adolescents reporting respiratory symptoms and attending high school in Detroit. The purpose for symptom-identification was to identify symptomatic students who would be eligible for enrollment in a school-based asthma management program designed specifically for urban teens. This report focuses on the implementation and cost of the symptom-identification process used.

Materials and Methods

Study methods were approved by the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) Institutional Review Board and the Detroit Public Schools (DPS) Office of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment. This project was conducted in collaboration with a DPS vendor, Computer Management Technologies (CMT), authorized to handle data processing and analysis of student records.

Caregivers of all 9th–11th graders of six Detroit public high schools were notified by mail of a respiratory health survey (Lung Health Survey) to be administered during a regularly scheduled English class in October of 2003. The notification letter was signed by the principal of the participating school. Caregivers could refuse to have their student participate by signing and returning the letter to the school. To maintain student confidentiality, mailings were conducted by CMT.

CMT developed scannable answer sheets corresponding to an asthma survey developed by HFHS. The asthma survey used items from nationally recognized instruments, and requested information on asthma diagnosis and the occurrence of respiratory symptoms. Students were also asked about health care utilization for symptoms, indicators of asthma severity, and indicators of asthma control (e.g., number of inhaler refills, number of days medication was needed for symptoms, and nights awakened due to symptoms).9, 10

The scannable answer sheets were pre-slugged (pre-printed) with student identification number, sex, race, date of birth and English class, and were distributed to all identified English teachers of the participating schools. English teachers were asked to administer the survey to all students during a regularly scheduled class within the next 2 weeks. Teachers were asked to return completed answer sheets to a designated contact person at each school who then forwarded the sheets to a central DPS location. CMT destroyed any answer sheets inadvertently completed by a student whose guardian had indicated refusal. English teachers and designated school contacts were given token compensation for their efforts.

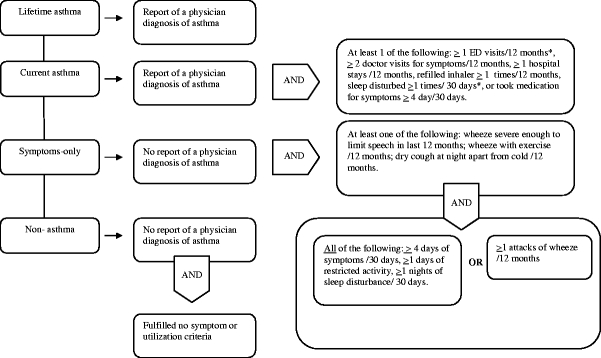

As the purpose of this procedure was to identify symptomatic students eligible for enrolling in a school-based asthma management program, and there is currently no consensus on a standard definition for asthma, the criteria for eligibility were developed using national resources, including the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel II Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma (Expert Panel II),9 the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) recommended case-definition of asthma for use in surveillance,11 and the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children (ISAAC) survey.12 Students were classified as lifetime asthma, current asthma, symptoms-only, or non-asthma (Figure 1). Further classification by asthma severity was accomplished by again referring to Expert Panel II guidelines. As done in previous studies, investigators interpreted and assigned numeric values when terms such as “frequent” and “continual” were used in the Expert Panel II criteria. 4–6, 13

Figure 1.

Criteria used in classification of students for program enrollment. */12 months = in the last 12 months; /30 days = in the last 30 days.

All students meeting criteria for current asthma or symptoms-only were invited to enroll in the school-based asthma management program. Information and invitations were mailed by CMT or distributed by school personnel. Student names and identifiers were not revealed to HFHS until parental consent was obtained.

Statistics

Confidence intervals for proportions were calculated using the asymptotic Gaussian method.14 When comparing current asthma or symptoms-only to non-asthma, a Student’s t-test was used to compare means for continuous variables and a Chi Square test was used for comparisons involving categorical variables.14 All calculations were performed using SAS 9.1 TS Level 1M2, Windows Version 5.2.3790.

Results

Six Detroit public high schools participated. Three of the participating schools had a school health clinic staffed by a school nurse. A total of 10,451 students in grades 9–11 were recorded as enrolled in the six participating schools, of which 7,446 students (71.2%) were assigned to an English class in October, 2003 (Figure 2). Less than 0.1% of parents refused to have their student participate. Forms for 5,967 students (80% of 7,446 or 57% of 10,451) were returned for 143 of 153 English teachers (93%). Of the ten non-participating teachers, eight were specialists in alternative curricula (special education), and accounted for an estimated 334 (22.6%) of the 1,479 unreturned forms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart for results of symptom-identification. *Students not recorded as being assigned to an English class as of October 2003.

Of the students assigned to an English class and completing a survey, 98.6% were African-American, and 52% qualified for federal school lunch programs. To obtain some idea of potential differences, students assigned an English class were compared to those unassigned, using 2005 data (2003 data unavailable at the time of this analysis). Unassigned students were more likely to be male (63% male, unassigned vs. 52% male, assigned), older (16.4 years, unassigned vs. 15.4 years, assigned), of lower SES (median household income/person for unassigned = $11,188 vs. 12,163 for assigned) and were more likely to be non-African American (3.7% non-African Americans, unassigned vs. 1.4% non-African American, assigned). The majority of the non-African Americans were assigned to the category “White, non-Hispanic” according to school records. All comparisons of assigned vs. unassigned students were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

The percentage (95% confidence interval) of students classified as lifetime asthma, current asthma, and symptoms-only was 15.8% (14.9–16.8), 11.0% (10.2–11.8), and 9.2% (8.5–9.9), respectively (Figure 2). Among those with current asthma, the percentage of students reporting an episode or attack of wheeze within the last year was 60.1% (56.4–63.9), or 394/655. There were no statistical differences for estimates of students meeting criteria for lifetime, current asthma, or symptoms-only across schools or between schools that had school nurses and those that did not (data not shown).

Results of the symptom-identification process appear in Table 1. Data are based on student answers to the Lung Health Survey. Students meeting criteria for current asthma (diagnosed) reported more adverse outcomes, in terms of school absenteeism, health care utilization, asthma control, and asthma severity when compared to symptoms-only students (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of symptom-identification for asthma and respiratory among Detroit high scholl students, grades 9–11a

| Variable | Current asthma | Symptoms-only | No asthma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| n = 655 | n = 550 | n = 4,472 | ||

| Age (mean, s.d.) | 15.1 ± 1.0 | 15.1 ± 1.1 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | ** |

| Female, n (%) | 344 (52.5) | 337 (61.3) | 2239 (50.1) | ** |

| Absenteeism in last 30 days | n = 634 | n = 502 | n = 3,431 | |

| ≥1 day (any reason) | 431 (68.0) | 343 (68.3) | 1662 (48.4) | * ** |

| n = 603 | n = 497 | n = 3,298 | ||

| ≥1 day (due to symptoms) | 227 (37.7) | 136 (27.4) | 205 (6.2) | * ** *** |

| Utilization/12 months | n = 623 | n = 519 | ||

| ≥1 asthma ED visit | 299 (48.0) | 132 (25.4) | *** | |

| n = 641 | n = 531 | |||

| ≥1 asthma hospitalization | 108 (16.9) | 44 (8.3) | *** | |

| n = 617 | n = 515 | |||

| ≥1 physician visit for symptoms | 373 (60.4) | 185 (35.9) | *** | |

| Asthma control (Rules of Two)10 | n = 634 | n = 520 | ||

| Used inhaler ≥2 times/week | 232 (36.6) | 64 (12.3) | *** | |

| n = 612 | n = 499 | |||

| Awakened ≥2 times /30 days | 262 (42.8) | 151 (30.3) | *** | |

| n = 636 | n = 529 | |||

| ≥2 refills/last year | 325 (51.1) | 49 (9.3) | *** | |

| Asthma severity | n = 646 | n = 528 | ||

| Mild, intermittent | 379 (58.7) | 400 (75.8) | *** | |

| Mild, persistent | 100 (15.5) | 55 (10.4) | *** | |

| Moderate | 78 (12.0) | 39 (7.4) | *** | |

| Severe | 89 (13.8) | 34 (6.4) | *** | |

adata is missing for some questionnaire items

*p < 0.05 for current vs. no-asthma; **p < 0.05 for symptoms-only vs. no-asthma; ***p < 0.05 for current vs. symptoms-only

Cost estimates were provided by CMT and reflect direct costs of providing the services outlined in Table 2. Teachers estimated about 15–20 min of class time was needed to administer the survey.

Table 2.

Estimated costs to vendor for symptom-identification protocol

| Task | Estimated cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Per student | Per completed form | Per Diagnosed studenta | Per eligible studentb | Total | |

| Enumerate students, teachers; print, sort, package Lung Health Surveys (LHS) | 9/2003 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 5.59 | 4.39 | 5,287.00 |

| Design and revision of scan sheets (answer sheets); begin program to create pre-slugged scan sheets | 0.54 | 0.67 | 4.23 | 3.32 | 4,000.00 | |

| Complete program to identify teacher, period, etc.; print and sort pre-slugged answer sheets | 0.44 | 0.55 | 3.46 | 2.72 | 3,275.00 | |

| Create/test mail merge for information letters mailed to homes announcing LHS, program bar coding; correct invalid addresses, etc. (e.g., remove “deceased” parents); obtain post office approval for bulk mailing | 1.01 | 1.26 | 7.95 | 6.24 | 7,520.87 | |

| Print, fold, tab, bar code announcement letters, drop-off letters to post officec; LHS and answer sheets delivered to central office for distribution to schools; sort/process returned answer sheets, create/test program to apply finalized eligibility algorithm | 10/2003 | 1.24 | 1.55 | 9.80 | 7.69 | 9,265.00 |

| Continue scan/sorting returned answer sheets; run special queries (e.g., check for students who may have completed surveys in more than one teacher) | 0.23 | 0.28 | 1.77 | 1.39 | 1,675.00 | |

| Create program to process/transfer answer sheets to IBM iSeries; hand-enter forms completed in ink, apply eligibility algorithm to LHS data, generate mailing labels for consent packets sent to homes of eligible students; scan barcoded consent forms; tag students returning consents; send comma-delimited file to HFHS with random number for link to identifiers of consenting students | 11/2003 | 1.06 | 1.32 | 8.34 | 6.54 | 7,884.48 |

| Total | $5.23 | $6.52 | $41.14 | $32.29 | $38,907.35 | |

aNumber of students reporting a physician diagnosis; bStudents fulfilling program enrollment criteria, i.e., current asthma or symptoms-only; cVendor located outside of Detroit

Discussion

Our main objective was to provide information useful to researchers or school administrators considering asthma programs requiring the identification of high school students with uncontrolled symptoms. Using a denominator of all English students, a high response rate was achieved, the per-student cost was relatively low, and student confidentiality was maintained.

English is a yearly curriculum requirement in DPS high schools, and targeting English classes resulted in capturing the majority of students. Using this denominator, students missed would include those using elective classes to fulfill English requirements and students who were yet unassigned at the time of the survey. Reasons for being unassigned in early fall include scheduling delays/changes, change of residence/school transfer, truancy, and routine record-keeping errors. Results suggest that asthma risk factors, such as low socioeconomic status, may be distributed differently among unassigned students. The efficiency of using English assignment as a denominator may be maximized by conducting the symptom-identification later in the school term when more students are likely to be assigned, and will also depend on curriculum requirements and the accuracy of scheduling for the school under study.

Our response rate is similar to the 83% student response rate reported in the CDC publication on self-reported asthma among US high school students using the 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).7 Using students that completed the survey as the denominator, the CDC was unable to provide a description of non-responders, and similarly, data was unavailable in this study for a comparison of assigned English students who completed a survey vs. those who did not. An estimated 23% of non-responders in the present study may have been special education. The remaining non-respondents may have been absent on the day of the survey. One national report showed high school absenteeism to range from 18–21%.7, 15, 16

Comparison across studies is difficult due to the lack of standardization for case-definitions of asthma and the lack of published information on asthma in urban, high school students. Table 3 is a summary of studies in similar populations6, 17–20. The definition and prevalence of lifetime asthma reported in this study (“Has a doctor ever told you that you have asthma?”) are both similar to that of the studies listed in Table 3, with the exception of the CDC report.7 The CDC definition of current asthma (a yes answer to “Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have you have asthma?” and a yes or no answer to “Have you had an episode of asthma in the past 12 months?”) is less stringent than the criteria used in the present study (Figure 1). Although present study criteria were adopted to minimize enrollment of false positives in the subsequent asthma program, the resulting prevalence of current asthma is still similar to those shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

US Population-based studies of asthma prevalence among adolescents

| Study population | Year | Lifetime asthma (%) | Current asthmaa (%) | Wheeze 12 monthsb (%) | ED visit (%)c | Hospital stay (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persky, 1998 [6] | 3,670 7th and 8th grade student in Chicago middle schools ≥98% African-American | 1994–1995 | 19.6 | 8.7 | 17.3 | 16.1 | 8.7 |

| Yeatts, 2000 [17] | 1,596 7th and 8th graders (13–14 years) in N Carolina, 18% African-American | Not given | 16.4 | 10.0 | 15 | 30.0 | Not given |

| Yeatts, 2001 [18] | 2,059 8th graders in Charlotte-Macklenburg N.Carolina school district; 33.7% African-American | 1996 | 17 for AA | 9.0 | 16 for AA | 11.9 | 3.8 |

| Fagan, 2001 [20] | 2,693 7–12th graders attending eight schools in East Moline, Illinois after MS flood, 6.1% African-American | 1994 | 16.4 | 12.6 | 25.1 | 6.4 for AA | 1.3 for AA |

| Yeatts, 2003 [19] | 122,829 7th and 8th graders of 565 N. Carolina public middle schools (12–14 yrs), 27% African-American | 1999–2000 | 16.0 | 11.0 | 27.2 | 30.1 | 23.1 |

| CDC 2003 YRBS, 2005 [7] | 13,553 students in grades 9–12; 50 states and DC; percentage African-American not given | 2003 | 18.9d | 16.1d | Not given | Not given | Not given |

| 21.3 for AAd | 16.8 for AAd | ||||||

| Joseph, 2006 | 5,963 9th–11th graders, 99% AA | 2003 | 15.8 | 11.0 | 21.3 | 48.0 | 16.9 |

AA = African American;

aReport diagnosis and symptoms/utilization in the last 12 months; bReported wheeze in last 12 months; cOf those students considered to have current and diagnosed asthma; dCDC weighted estimates.

The CDC 2003 YRBS did not collect further information on asthma morbidity or symptom frequency for high school students, as the intent was surveillance, but again, our results are similar to previous studies conducted among adolescents.7 Fagan et al., 2001, reported asthma morbidity for high school students, but only 6.1% of the study population was African-American.20 Our results support a need for asthma programs that target urban adolescents.

The estimated costs include services that could be eliminated or combined to reduce expenses. For example, costs for mass mailing may be reduced by including the parental notification letter in material already being sent to students’ homes. Costs of symptom-identification must include the class time needed to administer the survey.

Misclassification of students with possible asthma (symptoms-only) is a potential limitation of our study. The survey items selected correspond directly to those used in national and international surveys to identify persons with possible asthma, e.g., ISAAC, but this continues to be a major challenge for asthma epidemiologists. Moreover, the circumstances surrounding a report of symptoms without an accompanying diagnosis are unclear. For example, in the current study, 12% of students without a diagnosis reported use of an inhaler, and 9% reported 2 or more refills in the past year.

U.S. readiness for case-detection has been debated, however, there is a consensus in the medical and public health community that persons reporting uncontrolled symptoms should receive medical attention.1 At least two studies have shown positive outcomes after intervening with symptomatic students without a diagnosis of asthma, one of which also states that 30% of these children reported a physician diagnosis at follow-up. Given that some proportion of students reporting symptoms will not receive a diagnosis of asthma, it is unclear if case-detection is a cost-effective undertaking. To be effective, costs of case-detection and identification would need to be offset by a savings in the direct and indirect costs associated with asthma care. As such, most experts do not recommend case-detection for schools that do not have a system of follow-up and referral in place.

Students with uncontrolled respiratory symptoms are the most likely to benefit from school-based asthma management programs, if appropriate follow-up is available. The level of information described in this paper would be difficult to obtain from school health records alone. These results may be helpful to investigators, schools, and other groups designing school-based asthma programs.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate and acknowledge the collaboration of the Detroit Public School System and the principals of the following Detroit Public high schools: Cody, Henry Ford, Mackenzie, Mumford, Northwestern, and Redford. These principals exhibit a deep concern for the health and welfare of their students. We also acknowledge the valuable work of Ms. Kimberly Schalk and Edward “Mickey” Friedrich of Computer Management Technologies, and thank Ms. Anntinette McCain of the Office and Health and Safety and Ms. Sybil St. Clair of the Office of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment for their guidance and advice.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Grant # R01 HL068971-05.

Footnotes

Joseph, Stringer, Havstad, Johnson, Williams, and Peterson are with the Department of Biostatistics & Research Epidemiology, Detroit, MI, USA; Baptist is with the Allergy—Immunology Section, Division of General Internal Medicine, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA; Ownby is with the Allergy—Immunology Section, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA.

References

- 1.Boss LP, Wheeler LSM, WIlliams PV, Bartholomew LK, Taggart VS, Redd SC. Population-based screening or case detection for asthma: are we ready? J Asthma. 2003;40(4):335–342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(1):1–13, Mar 29. [PubMed]

- 3.Wheeler LS, Boss LP, Williams PV. School-based approaches to identifying students with asthma. [Review] [16 refs]. J Sch Health. 2004;74(9):378–380, Nov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Joseph CLM, Foxman B, Leickly FE, Peterson E, Ownby DR. Prevalence of possible undiagnosed asthma and associated morbidity among urban schoolchildren. J Pediatr. 1996;129:735–742. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Clark NM, Brown R, Joseph CL, et al. Issues in identifying asthma and estimating prevalence in an urban school population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):870–881, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Persky VW, Slezak J, Contreras A, et al. Relationships of race and socioeconomic status with prevalence, severity, and symptoms of asthma in Chicago school children. Ann Allergy Asthma & Immun. 1998;81(3):266–271, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Self-reported asthma among high school students—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2005;54(31):765–767, Aug 12. [PubMed]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy Women: State Trends in Health and Mortality. http://www.cdc.gov/search.do?action=search&queryText=healthy+women%3A+state+trends+in+health+and+mortality&image.x=8&image.y=8. Accessed March 4, 2005.

- 9.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel report 2. United States Department of Health and Human Services NIH Publication No 97-4051 1997 Apr.

- 10.©2001 Baylor Health Care System. All rights reserved. Rules of Two® is a federally registered service mark of Baylor Health Care System. http://www.baylorhealth.com/medicalspecialties/asthma/asthmaprograms.htm#Rof2.

- 11.CDC. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists asthma surveillance definition. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Environmental Health, 2001. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/asthma/casedef.htm.

- 12.Weiland SK, Bjorksten B, Brunekreef B, Cookson WO, von ME, Strachan DP. Phase II of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC II): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(3):406–412, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Joseph CL, Havstad S, Anderson EW, Brown R, Johnson CC, Clark NM. Effect of asthma intervention on children with undiagnosed asthma. J Pediatr. 2005;146(1):96–104, Jan. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fleiss J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Second ed. New York, New York: Wiley; 1981.

- 15.Besculides M, Heffernan R, Mostashari F, Weiss D. Evaluation of school absenteeism data for early outbreak detection, New York City. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:105, Oct 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wirt J, Choy S, Gerald D, et al. The condition of education 2002. National Center for Education Statistics 2002;NCES 2002-025:71.

- 17.Yeatts K, Shy C, Wiley J, Music S. Statewide adolescent asthma surveillance. J Asthma. 2000;37(5):425–434, Aug. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Yeatts K, Shy C. Prevalence and consequences of asthma and wheezing in African-American and White adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(5):314–319, Nov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Yeatts K, Shy C, Sotir M, Music S, Hergot C. Health consequences for children with undiagnosed asthma-like symptoms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(6):540–544, Jun. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Fagan JK, Scheff PA, Hryhorczuk D, Ramakrishnan V, Ross M, Persky V. Prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in an adolescent population: association with gender and race. Ann Allergy Asthma & Immun. 2001;86(2):177–84, Feb. [DOI] [PubMed]