Trends in hypotensive drug use have been reported using administrative databases for patients with glaucoma or suspected glaucoma.1-4 We used verified patient self-reported data from the 1992–2002 waves of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) merged with Medicare claims data to report rates and trends of glaucoma medication usage. The MCBS involves annual face-to-face interviews with a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries, including verification of drug use, when possible, by on-site inspection of participants' drug containers. Additional information about the MCBS can be obtained at www.cms.hhs.gov/LimitedDataSets/11_MCBS.asp.(accessed October 15, 2006)

Our analysis excluded beneficiaries younger than 65 at the interview date. After this exclusion, the MCBS samples ranged from 11,884 in 1996 to 13,106 in 1999. We identified glaucoma suspects from these samples by using these ICD-9-CM codes: 365.0, 365.00, 365.01, 365.04, 365.24. For inclusion in the analysis, MCBS participants needed to have had at least one diagnostic code for suspected glaucoma in the preceding year, and none for other glaucoma types. (Supplemental Material at AJO.com)

Drugs were classified by therapeutic category: α-adrenergic agonists, β-blockers, epinephrine compounds, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), prostaglandin analogues (PGAs), topical CAIs, or combination β-blocker–topical CAIs. We calculated annual percentages of participants reporting use of at least one drug in the category in the year before the interview. We also calculated annual percentages of participants reporting no hypotensive drug use; for this subset, we also computed the percentages undergoing glaucoma-related laser and incisional surgeries.

The annual number of survey participants with suspected glaucoma ranged from 338 in 1996 to 476 in 2000 (mean, 407). The annual percentage of glaucoma suspects using no hypotensive medication ranged from 86% to 91% (Table 1). Among medically untreated patients in a given year, fewer than 1% underwent glaucoma surgery (Table 2).

Table 1.

Proportion of Glaucoma Suspects Aged 65 Years and Older Using Hypotensive Medication, by Type of Drug Used (If Any), according to Survey Year, MCBS, 1992–2002

| Class of Drug Used | Patients with Suspected Glaucoma, by Year |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1992 (N=359) |

1993 (N=399) |

1994 (N=422) |

1995 (N=371) |

1996 (N=338) |

1997 (N=380) |

1998 (N=412) |

1999 (N=447) |

2000 (N=476) |

2001 (N=461) |

2002 (N=409) |

All Years (N=407) |

|

| α-agonists | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 1.6 |

| β-blockers | 10.0 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 11.3 | 8.9 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.2 |

| Epinephrine compounds | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Miotics | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Oral CAIs | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Prostaglandins | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 2.5 |

| Topical CAIs | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Topical CAI–β-blocker | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| None | 88.1 | 85.6 | 85.9 | 86.3 | 89.1 | 90.5 | 87.4 | 86.2 | 86.6 | 90.0 | 87.8 | 87.5 |

NOTES: In the column for any given year, the numeral shown in parentheses is the total number of glaucoma suspects surveyed. In the all years column, the numeral in parentheses and the percentages are means. Data reported in the table are based on a total of 4474 person-years observed.

Table 2.

Percentage of Medically Untreated Glaucoma Suspects Aged 65 Years and Older Undergoing Glaucoma Surgery, by Type of Procedure, according to Survey Year, MCBS, 1992–2002

| Type of Surgery | Medically Untreated Patients, by Year |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1992 (N=318) |

1993 (N=344) |

1994 (N=364) |

1995 (N=320) |

1996 (N=302) |

1997 (N=344) |

1998 (N=360) |

1999 (N=386) |

2000 (N=412) |

2001 (N=416) |

2002 (N=360) |

All Years (N=357) |

|

| Incisional | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Laser | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

NOTES: Numerals in the column labeled all years are means. Data reported in the table are based on 3926 person-years of observation.

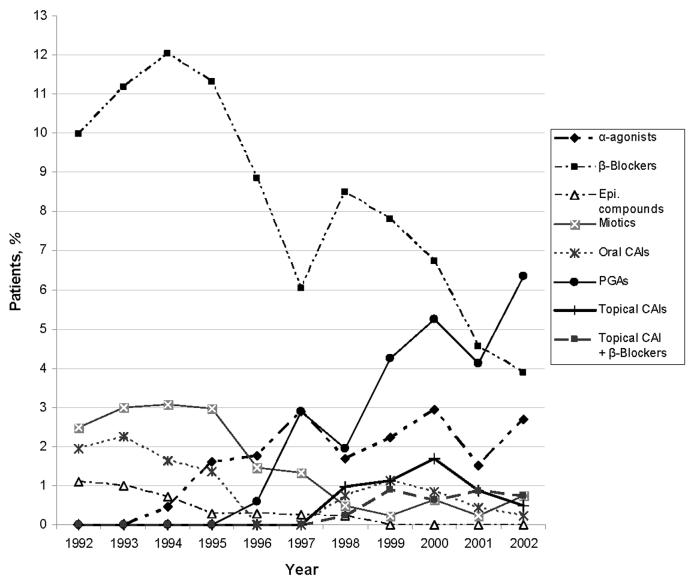

The percentages of glaucoma suspects taking β-blockers, miotics, epinephrine compounds, and oral CAIs decreased over 1992–2002, whereas use of α-agonists, combination β-blocker–CAIs, and PGAs increased (Figure 1). By 2002, PGAs had surpassed β-blockers as the most utilized hypotensive drug class. (Supplemental Material at AJO.com)

Figure 1.

Use of hypotensive medications among all patients aged 65 years and older with suspected glaucoma, by drug class, according to year, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 1992—2002.

CAIs = carbonic anhydrase inhibitors; epi. = epinephrine; PGAs = prostaglandin analogues.

A major finding of our analysis is that from 1992–2002, more than four-fifths of beneficiaries with diagnosed suspected glaucoma used no therapy. Also noteworthy is the dramatic shift in utilization from β-blockers and miotics to PGAs and α-agonists.

In 2002, the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS)—the first large, randomized, controlled trial of therapy for ocular hypertension—reported that hypotensive-drug use significantly reduces the risk of glaucoma among ocular hypertensives.5 OHTS also identified risk factors for progression that clinicians can use to make an informed decision whether to initiate treatment.6 It will be interesting to continue following glaucoma medication use trends among ocular hypertensives to determine this study's impact on utilization rates.

Considering that 3–6 million persons in the United States have suspected glaucoma,7 an understanding of trends in glaucoma medication use is important for health policy-making. The recent sharp increase in PGA use is unsurprising given their effectiveness at reducing intraocular pressure, their favorable side-effect profile, and their once-daily administration. Future policy-makers must decide whether PGAs' many benefits justify their costs. Such determinations will depend partly on whether increased PGA use would improve patient adherence; slow or halt disease progression; and reduce the need for costly, more invasive interventions in the future.

Instead of relying on information from pharmacy-dispensing databases or from prescribing records in patient charts, our analysis used a more direct measure of patients' actual drug use—patient self-reports coupled with interviewer verification of the drug containers. We acknowledge these few limitations. Since Medicare claims data are unavailable for beneficiaries enrolled in managed-care plans, the data do not capture drug use among that subset of beneficiaries. Moreover, since we excluded persons younger than 65, the utilization rates we report may not be representative of all U.S. glaucoma suspects. Nonetheless, these findings, from a nationally representative database, offer important insights into recent patterns of glaucoma medication use among older U.S. adults with suspected glaucoma.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Padmaja Ayyagari MA, Department of Economics, Duke University, for valuable research assistance.

Appendix 1: Additional Details About Methods

Although the MCBS uses a repeated measures design (4 year rotating panel design with repeat measures 3 times within each year) information about beneficiary medication usage was obtained only once a year. A beneficiary may have been in the study for multiple years, but each year was a separate estimate.

Since the accuracy of ICD-9 coding is frequently driven by its use for billing applications rather than scientific studies, in addition to assessing the utilization patterns for all five of the glaucoma suspect codes together, we also analyzed the data using only the ICD-9 codes 365.01, 365.04, 365.24 to ensure that we were not overestimating drug use due to clincians miscoding manifest glaucoma using the codes 365.0 or 365.00.

Trend regressions were performed for each drug class to determine whether the changes in medication use over the decade were significant.

Appendix 2: Additional Results

When using all 5 glaucoma suspect codes, the annual rates of beneficiaries untreated medically or surgically ranged from 84.9% to 90.1%. Using the ICD-9 codes 365.01, 365.04, 365.24 only, the annual rate of beneficiaries untreated medically or surgically ranged from 81.5% to 90.1%. Using only the 365.0 glaucoma suspect code, the annual rate of beneficiaries untreated medically or surgically ranged from 81.7% to 89.3%. Using only the 365.00 glaucoma suspect code, the annual rate of beneficiaries untreated medically or surgically ranged from 85.0% to 90.3%.

We performed trend regressions and determined that all time trends are statistically significant at p <0.01 levels or better for each glaucoma medication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Funding /Support: This research was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging (grant no. 2R 37-AG-17473-05A1) and the Heed Ophthalmic Foundation.

Financial Disclosures: None for all of the authors

Online material for “Rates of Glaucoma Medication Utilization Among Older Adults with Suspected Glaucoma, 1992-2002.”

Supplemental Material available at AJO.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Carroll SC, Gaskin BJ, Goldberg I, Danesh-Meyer HV. Glaucoma prescribing trends in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34(3):213–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calissendorff BM. Consumption of glaucoma medication. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79(1):2–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2001.079001002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spooner JJ, Bullano MF, Ikeda LI, et al. Rates of discontinuation and change of glaucoma therapy in a managed care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(10 Suppl):S262–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DS, Nordstrom B, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA. Glaucoma management among individuals enrolled in a single comprehensive insurance plan. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(9):1500–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robin AL, Frick KD, Katz J, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: intraocular pressure lowering prevents the development of glaucoma, but does that mean we should treat before the onset of disease? Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(3):376–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibowitz HM, Krueger DE, Maunder LR, et al. The Framingham Eye Study monograph: An ophthalmological and epidemiological study of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and visual acuity in a general population of 2631 adults, 1973-1975. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24(Suppl):335–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]