Abstract

PURPOSE The aim of this study was to determine the information needs of primary care physicians in Spain and to describe their information-seeking patterns.

METHODS This observational study took place in primary care practices located in Madrid, Spain. Participants were a random stratified sample of 112 primary care physicians. Physicians’ consultations were video recorded for 4 hours. Clinical questions arising during the patient visit and the sources of information used within the consultation to answer questions were identified. Physicians with unanswered questions were followed up by telephone 2 weeks later to determine whether their questions had since been answered and the sources of information used. Clinical questions were classified by topic and type of information.

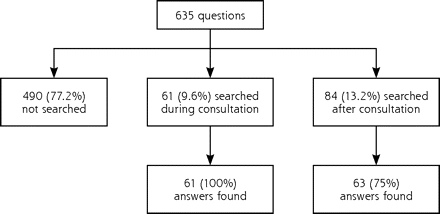

RESULTS A total of 3,511 patient consultations (mean length, 7.8 minutes) were recorded, leading to 635 clinical questions (0.18 questions per consultation). The most frequent questions were related to diagnosis (53%) and treatment (26%). The most frequent generic type of questions was “What is the cause of symptom x?” (20.5%). Physicians searched for answers to 22.8% of the questions (9.6% during consultations). The time taken and the success rate in finding an answer during a consultation and afterward were 2 minutes (100%) and 32 minutes (75%), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS Primary care physicians working in settings where consultations are of short duration have time to answer only 1 in 5 of their questions. Better methods are needed to provide answers to questions that arise in office practice in settings where average consultation time is less than 10 minutes.

Keywords: Information seeking, clinical questions, knowledge translation, primary health care, medical informatics, information systems, information resources, office visits

INTRODUCTION

Physicians cannot practice high-quality medicine without constantly updating their clinical knowledge to help them manage patients. In primary care, each practitioner encounters more than 500 clinical topics in any year,1 so the information need is much broader than that of other specialties, which may in turn lead to specific problems for these clinicians searching many resources for answers.

Experienced physicians use about 2 million pieces of information to manage their patients.2 Most of the information physicians use when seeing patients is obtained from their memory and, unfortunately, some is out of date or wrong.2

The development of medical informatics has produced systems that help physicians in their daily practice by providing them with information, but these systems have often failed to fulfill expectations in part due to the lack of knowledge about the information needs of family physicians.3–15 Question generation has frequently been based on relatively small populations of primary care physicians listing their questions after consultations, often some time later. Information-seeking behavior has often been based on general cases or on hypothetical cases with little validation of actual question-answering behavior. To date, we could find no real-time observed evaluations of primary care physicians’ information-seeking processes.

The main aim of the study was to determine the information needs and information-seeking patterns of a random representative sample of primary care physicians seeing patients in practices where consultations are of short duration.

METHODS

Participants

The study population consisted of a sample of all primary care physicians working in primary care practices located in Madrid, Spain, from May 2002 through June 2004. Family practice residents, locum tenens, and physicians with teaching or research contracts at universities were excluded. We invited to participate a randomly selected sample of 208 physicians stratified by area (rural or urban) and specialty (family physician or pediatrician), of whom 112 (54%) agreed. Random selection was performed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill).

Measures

The physicians were initially invited by telephone to participate and be observed using video recording during 4 hours of consultation without modifying their practice behavior. They were asked to identify, after seeing each patient, all clinical questions related to the care of that patient occurring during the consultation. This identification was achieved by the physician facing the video recorder and speaking their questions out loud in between each patient consultation. We used this methodology because it was an easy way to capture questions and avoided the need for physicians to write down all the questions or be interviewed by a third party, which would have delayed their practice.

Questions, sources of information, and time taken for answering questions during the consultation were identified and classified by 3 clinician-researchers after reviewing each of the videotaped consultations and the questions asked by the clinician at the end of each consultation. The questions were classified by type (eg, treatment, diagnosis) and topic (eg, adult medicine, pediatrics) using the taxonomies developed by Ely and colleagues.13 This classification was performed by the 3 researchers working together to achieve consensus.

To determine whether answers were obtained to questions that remained unanswered at the end of the consultation with the patient, we undertook telephone interviews of all the physicians 2 weeks after their videotaped consultations. The method of retrieval, the time used to find the answers outside the office, and barriers to finding answers were determined during these interviews.

Our main outcome measures were the number of questions asked, pursued, and answered; the type and topic of each question; the time spent pursuing answers; the information resources used; and the perceived barriers to searching for information.

Statistical Analysis

We computerized and analyzed data using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) and Epidat version 3.0 (Pan American Health Organization, Washington, DC). Descriptive data were obtained by using SPSS. We used the Student t test to compare means.

RESULTS

A total of 112 primary care physicians (90 family physicians and 22 pediatricians) participated. The mean age of participants was 42 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 41–44); 62% were female. Although 70 physicians had a computer at their office, only 31 of them had access to the Internet. Forty-one of the physicians were tutors in the family practice residency program, and 27 had a resident within their practice during the study period. No differences were found in the characteristics described between those who participated and those who did not, except that tutors and physicians with access to the Internet tended to participate more frequently.

The 112 physicians saw a total of 3,511 patients during the 4-hour observation periods, with an average consultation length of 7.8 minutes per patient.

These 3,511 consultations generated 635 questions about patient care, with an average of 1.8 questions (95% CI, 1.68–1.94) for every 10 patients seen.

The wide variation of clinical and administrative problems seen in primary care is reflected in the results in Table 1 ▶. From these 52 topics, we grouped the questions using the taxonomy of Ely et al,13 as shown in Table 2 ▶. The most frequent questions were related to diagnosis (53%) and treatment (26%). Management (7%), epidemiologic (1%), and nonclinical (13%) questions made up the remainder. The 10 most frequent questions are shown in Table 3 ▶.

Table 1.

Clinical Topics of the 635 Clinical Questions Asked by 112 Spanish Primary Care Physicians During 3,511 Consultations

| Topic | No. (%) | 95% CI |

| Pharmacology or prescribing information | 61 (9.6) | 7.2–12 |

| Diagnostic process | 59 (9.3) | 7–12.7 |

| Dermatology | 53 (8.3) | 6.1–10.6 |

| Orthopedics | 50 (7.9) | 5.7–10 |

| Administration | 34 (5.4) | 3.5–7.2 |

| Adult gastroenterology | 32 (5.0) | 3.3–6.8 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 28 (4.4) | 2.7–6.1 |

| Otolaryngology | 28 (4.4) | 2.7–6.1 |

| Pediatric infectious disease | 21 (3.3) | 1.8–4.8 |

| Adult respiratory disease | 20 (3.1) | 1.7–4.6 |

| Adult psychiatry | 17 (2.7) | 1.3–4.0 |

| Adult dermatology | 16 (2.5) | 1.2–3.8 |

| Ophthalmology | 16 (2.5) | 1.2–3.8 |

| General surgery | 15 (2.4) | 1.1–3.6 |

| Adult neurology | 15 (2.4) | 1.1–3.6 |

| Adult cardiovascular disease | 14 (2.2) | 0.9–3.4 |

| Medical ethics | 13 (2.0) | 0.9–3.2 |

| Family practice | 13 (2.0) | 0.9–3.2 |

| Urology | 11 (1.7) | 0.6–2.8 |

| Clinical interview | 10 (1.6) | 0.5–2.6 |

| Adult endocrinology | 10 (1.6) | 0.5–2.6 |

| Preventive medicine and screening | 9 (1.4) | 0.4–2.4 |

| Adult infectious disease | 9 (1.4) | 0.4–2.4 |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 7 (1.1) | 0.2–1.9 |

| Pediatric respiratory disease | 7 (1.1) | 0.2–1.9 |

| Radiology | 6 (0.9) | 0.1–1.8 |

| Legal issues | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–1.8 |

| Patient education | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–1.8 |

| Pediatric rheumatology | 4 (0.6) | 0.2–1.6 |

| Adult allergy and immunology | 4 (0.6) | 0.2–1.6 |

| Adult hematology | 4 (0.6) | 0.2–1.6 |

| Pediatric gastroenterology | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Geriatrics | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Laboratory medicine | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Neurosurgery | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Adult oncology | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Child psychiatry | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| Occupational medicine | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| Dentistry | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| General pediatrics | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| Pediatric allergy and immunology | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| Pediatric endocrinology | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| Pediatric neurology | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| General internal medicine | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Anesthesiology | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Adult nephrology | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Nutrition | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Alternative medicine | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Thoracic surgery | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Vascular surgery | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Therapeutic process | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

CI = confidence interval.

Table 2.

Description of 635 Questions Asked by 112 Spanish Primary Care Physicians During 3,511 Consultations, Using the Taxonomy of Ely et al13

| Code | Primary | Secondary | Description | No. (%) | 95% CI |

| 1.1.1.1 | Diagnosis | Cause/interpretation of clinical finding | What is the cause of symptom x? | 130 (20.5) | 17.3–23.7 |

| 1.1.2.1 | Diagnosis | Cause/interpretation of clinical finding | What is the cause of physical finding x? | 95 (15.0) | 12.1–17.8 |

| 1.1.3.1 | Diagnosis | Cause/interpretation of clinical finding | What is the cause of test finding x? | 19 (3.0) | 1.6–4.4 |

| 1.1.4.1 | Diagnosis | Cause/interpretation of clinical finding | Could this patient have condition y given findings x1, x2, …, xn? | 39 (6.1) | 4.2–8.1 |

| 1.2.1.1 | Diagnosis | Criteria/manifestations | What are the manifestations (findings) of condition y? | 6 (0.9) | 0.1–1.8 |

| 1.3.1.1 | Diagnosis | Test (laboratory, ECG, imaging, biopsy, skin test, element of physical examination, etc) | Is test x indicated in situation y? | 20 (3.1) | 1.7–4.6 |

| 1.3.2.1 | Diagnosis | Test (laboratory, ECG, imaging, biopsy, skin test, element of physical examination, etc) | How good is test x in situation y? | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 1.3.3.1 | Diagnosis | Test (laboratory, ECG, imaging, biopsy, skin test, element of physical examination, etc) | When (timing, not indications) should I do test x? | 11 (1.7) | 0.6–2.8 |

| 1.3.4.1 | Diagnosis | Test (laboratory, ECG, imaging, biopsy, skin test, element of physical examination, etc) | What is the preparation for test x? | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| 1.3.5.1 | Diagnosis | Test (laboratory, ECG, imaging, biopsy, skin test, element of physical examination, etc) | How do you do test x? | 7 (1.1) | 0.2–1.9 |

| 1.4.1.1 | Diagnosis | Name finding | — | — | — |

| 1.4.2.1 | Diagnosis | Name finding | — | — | — |

| 1.4.3.1 | Diagnosis | Name finding | — | — | — |

| 1.5.1.1 | Diagnosis | Orientation | — | — | — |

| 1.5.2.1 | Diagnosis | Orientation | — | — | — |

| 1.6.1.1 | Diagnosis | Inconsistencies | Why were this patient’s findings (or course) inconsistent with usual expectations? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 1.7.1.1 | Diagnosis | Cost | — | — | — |

| 1.8.1.1 | Diagnosis | Not elsewhere classified | Diagnosis, generic type, varies | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 2.1.1.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | How do you prescribe/administer drug x (in situation y)? | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 2.1.1.2 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | What is the dose of drug x? | 18 (2.8) | 1.5–4.2 |

| 2.1.1.3 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | When (timing, not indication) or how should I start/stop drug x? | 13 (2.0) | 0.9–3.2 |

| 2.1.2.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | Is drug x (or drug class x) indicated in situation y or for condition y? | 47 (7.4) | 5.5–9.7 |

| 2.1.2.2 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.1.3.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | Could finding y be caused by drug x? | 9 (1.4) | 0.4–2.4 |

| 2.1.3.2 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | How can drug x be administered without causing adverse effect y or minimizing adverse effect y or in spite of adverse effect y? | 2 (0.3) | 0.04–1.1 |

| 2.1.3.3 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | Is drug x safe to use in situation y? | 11 (1.7) | 0.6–2.8 |

| 2.1.4.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | Is it OK to use drug x with drug y? | 11 (1.7) | 0.6–2.8 |

| 2.1.5.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | What is the name of that drug? | 12 (1.9) | 0.8–3.0 |

| 2.1.6.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | What is drug x? | 7 (1.1) | 0.2–1.9 |

| 2.1.7.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | What are the physical characteristics (dosage forms, tablet/liquid characteristics, container characteristics) of drug x? | 9 (1.4) | 0.4–2.4 |

| 2.1.8.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.1.9.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.1.10.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.1.11.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.1.12.1 | Treatment | Drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.2.1.1 | Treatment | Not limited to but may include drug prescribing | How should I treat finding/condition y (given situation z)? | 15 (2.4) | 1.1–3.6 |

| 2.2.1.2 | Treatment | Not limited to but may include drug prescribing | Should this kind of patient get prophylactic treatment (intervention) x to prevent condition y? | 9 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 2.2.2.1 | Treatment | Not limited to but may include drug prescribing | When (or how) should I start/stop treatment x? | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 2.2.3.1 | Treatment | Not limited to but may include drug prescribing | How do you do treatment/procedure x? | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 2.2.4.1 | Treatment | Not limited to but may include drug prescribing | — | — | — |

| 2.3.1.1 | Treatment | Not elsewhere classified | Why is drug x not effective in condition y? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 3.1.1.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Condition/finding | How should I manage condition/finding/ situation y (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic management)? | 29 (4.6) | 2.9–6.3 |

| 3.2.1.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Other clinicians | — | — | — |

| 3.2.2.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Other clinicians | When should you refer in situation y? | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–1.8 |

| 3.2.3.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Other clinicians | — | — | — |

| 3.3.1.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Physician-patient communication | How should I advise the patient/family in situation y? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 3.3.2.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Physician-patient communication | What is the best way to discuss or approach discussion of difficult issue x? | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–1.8 |

| 3.3.3.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Physician-patient communication | How can I get the patient/family to comply with my recommendations or agree with my assessment? | 4 (0.6) | 0.2–1.6 |

| 3.4.1.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | Not elsewhere classified | Management, generic type, varies | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 4.1.1.1 | Epidemiology | Prevalence/incidence | What is the incidence/prevalence of condition y (in situation z)? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 4.2.1.1 | Epidemiology | Etiology | Is x a risk factor for condition y? – or – Is x associated with condition y? | 4 (0.6) | 0.2–1.6 |

| 4.2.1.2 | Epidemiology | Etiology | Is condition y hereditary? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 4.3.1.1 | Epidemiology | Course/prognosis | What is the usual course (or natural history) of condition y? | 1 (0.2) | 0.004–0.9 |

| 4.4.1.1 | Epidemiology | Not elsewhere classified | — | — | — |

| 5.1.1.1 | Nonclinical | Education | I need to learn more about topic x. | 18 (2.8) | 1.5–4.2 |

| 5.1.1.2 | Nonclinical | Education | Where can I find or how can I get information about topic x? | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 5.1.1.3 | Nonclinical | Education | — | — | — |

| 5.1.2.1 | Nonclinical | Education | — | — | — |

| 5.2.1.1 | Nonclinical | Administration | What are the administrative rules/considerations in situation y? | 35 (5.5) | 3.3–6.8 |

| 5.3.1.1 | Nonclinical | Ethics | What are the ethical considerations in situation y? | 13 (2.0) | 0.9–3.2 |

| 5.4.1.1 | Nonclinical | Legal | What are the legal considerations in situation y? | 5 (0.8) | 0.3–1.8 |

| 5.5.1.1 | Nonclinical | Frustration | Generic type, varies. Not a true question, but rather an expression of frustration or an unanswerable dilemma. | 3 (0.5) | 0.09–1.4 |

| 5.6.1.1 | Nonclinical | Not elsewhere classified | In a broad sense, the question is nonclinical, but it does not fit any other nonclinical category. | 6 (0.9) | 0.1–1.8 |

| 6.1.1.1 | Unclassified | — | — | — | — |

ECG = elecrocardiogram; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3.

Ten Most Frequent Questions Asked by 112 Spanish Primary Care Physicians During 3,511 Consultations

| Rank | Code of Ely et al13 | Category | Description | Frequency % |

| 1 | 1.1.1.1 | Diagnosis | What is the cause of symptom x? | 20.5 |

| 2 | 1.1.2.1 | Diagnosis | What is the cause of physical finding x? | 15.0 |

| 3 | 2.1.2.1 | Treatment | Is drug x (or drug class x) indicated in situation y or for condition y? | 7.4 |

| 4 | 1.1.4.1 | Diagnosis | Could this patient have condition y given findings x1, x2, … , xn? | 6.1 |

| 5 | 5.2.1.1 | Nonclinical | What are the administrative rules/considerations in situation y? | 5.0 |

| 6 | 3.1.1.1 | Management (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic) | How should I manage condition/finding/situation y (not specifying diagnostic or therapeutic management)? | 4.6 |

| 7 | 1.3.1.1 | Diagnosis | Is test x indicated in situation y? | 3.1 |

| 8 | 1.1.3.1 | Diagnosis | What is the cause of test finding x? | 3.0 |

| 9 | 2.1.1.2 | Treatment | What is the dose of drug x? | 2.8 |

| 10 | 5.1.1.1 | Nonclinical | I need to learn more about topic x. | 2.8 |

The clinicians chose to try to answer 145 (22.8%) of all questions. They tried to answer 61 (9.6%) of the questions during the consultation and 84 (13.2%) after the consultation. When they chose to search during the consultation, they were successful 100% of the time; in contrast, for searches performed after the consultation, their success rate was 75% (Figure 1 ▶). Physicians found answers for 124 (19.5%) of all questions that arose, with an overall success rate of 85.5% of all questions for which searches were performed.

Figure 1.

Information needs and information-seeking behavior of 112 Spanish primary care physicians during 3,511 consultations.

The sources of information used differed between searches performed during consultations and searches performed afterward (Table 4 ▶). Physicians spent very little time (mean, 2.25 minutes; median, 1 minute; 95% CI, 1.23–3.27) searching for answers during consultations, compared with after consultations had finished (mean, 32.27 minutes; median, 15 minutes; 95% CI, 23.81–40.73) (P <.001).

Table 4.

Resources Used by 112 Spanish Primary Care Physicians in Seeking Answers to Clinical Questions

| Resource Used for Searching | Total No. (%) | Searched During Consultation* No. (%) | Searched After Consultation No. (%) | Answers Found After Consultation No. (%) |

| Drug compendium | 61 (39.6) | 40 (65.6) | 11 (13.1) | 8 (12.7) |

| Colleagues | 19 (12.3) | 12 (19.7) | 7 (8.3) | 6 (9.5) |

| Others | 10 (6.5) | 6 (9.8) | 4 (4.8) | 4 (6.3) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (1.9) | 3 (4.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) |

| Books | 26 (16.9) | — | 26 (31) | 17 (27) |

| Journals | 15 (9.7) | — | 15 (17.9) | 9 (14.3) |

| Specialist | 8 (5.2) | — | 8 (9.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| Pharmaceutical representative | 7 (4.5) | — | 7 (8.3) | 6 (9.5) |

| Databases on Internet | 5 (3.2) | — | 5 (6.0) | 5 (7.9) |

| Total | 154 | 61 | 84 | 63 |

* Answers were found for all questions for which physicians searched for answers during the consultation.

When the physicians were asked at 2 weeks about their reasons for not pursuing an answer, they most commonly stated that they had not remembered the question posed (21%), did not think searching was necessary (20%), did not have the time (14%), or preferred to refer the patient to a specialist (14%).

DISCUSSION

Limitations of the Study

Part of the problem with comparing data on information seeking is the differing availability of information sources and the differing lengths of consultations between primary care settings. Our physicians did not use the Internet as frequently as found in other studies,16 but it was not available in 72% of the physician’s offices. In 6 European countries, the mean length of consultations is 10.7 minutes (SD, 6.7),17,18 which is much shorter than that seen in other comparable studies. The results from our study relate to practices with an even shorter consultation length, averaging 8 minutes. This time is less than that seen in many countries, and different information-seeking behaviors may be found in settings with longer consultations.

This was a self-selected sample of physicians who had a more academic practice and who agreed to a request to be videotaped. It is possible that the information-seeking behavior of this group might have differed from that of the physicians not interested in taking part.19

Rate of Question Formulation

The rate of questions found in this study (0.18 per consultation) is in the lower range of those found in other studies (0.07–1.85).20 This difference may be explained by the very short duration of consultations in comparison with those in other studies.

Types of Questions

There is, however, considerable similarity between the types of questions found in this study and the types found by Ely and colleagues.13 Only 2 of the top 10 questions in their list (“How should I treat condition x?” and “Can drug x cause (adverse) finding y?”) derived from doctors in Iowa and Oregon did not appear in our top 10. This similarity in most common questions supports the use of the taxonomy and the feasibility of categorizing questions in primary care within different settings and consultations styles. In addition to the original taxonomy of Ely et al,13 we found administration, which has been observed by others,21 and the physician’s expressed need for more education appearing among these most frequent questions.

The wide range of topics that the questions covered reflects the broad scope of practice found in primary care.1 All previous studies show that there is a tremendous variety to the questions primary care physicians ask, and these questions are often complex and patient specific.5,6,8 Again, our data confirm that even in this very fast paced setting, the same breadth of questions arises.

Question Answering

Previous studies have shown that the accessibility of the source of information rather than the quality of sources is a major determinant of which source is chosen when the need for information arises.12,22–24 We were not surprised to see a low rate of Internet searching, but we were surprised that physicians did not make use of secondary electronic sources such as InfoRetriever, Epocrates, Family Practice Inquiries Network, or other similar databases.24 The English language of these information sources may be an explanation for their poor use in this Spanish-language setting.

Physicians tried to find an answer to only 23% of the questions in this study, which is lower than the percentage reported by others,15 but when they did try to find an answer to a question, they were remarkably successful (86%). These findings indicate an extraordinarily selective process in identifying questions likely to yield answers quickly. The speed of answering questions during the consultation (2.2 minutes) was much faster than that cited by others.10,11,14

We confirmed that the source most frequently providing an answer remained a drug compendium, a textbook, or a colleague. What we have not been able to do is check the validity of the answers found using the various sources in actual practice. The pattern of response we found is, however, similar to that in other published studies wherein one half of the answers came from textbooks and human sources.25

Two characteristics that predict whether physicians will seek and find the answer to a clinical question are the urgency of the problem and their confidence that they will find an answer.11,15 In this study, the most common reason for not searching during the consultation was that physicians believed a decision could be based on their current knowledge without the need for searching, confirming similar findings by others.6,15

In conclusion, it may be necessary to tailor different methods to provide answers to questions that arise in various office settings with differing consultation lengths and access to information resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ENIGMA member team and all the primary care physicians who participated in the study. Without them the project would not have been possible. ENIGMA team: María Isabel Fernández San Martín, MD, PhD; Pilar Domenech Senra, MD; Juan Carlos Muñoz García, MD; Agustín Silva Mato, PhD; Luisa Cabello Ballesteros, MD; and José María Martín Moros, MD.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This study was supported by the following grants: Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria/Fondos Europeos de Desarrollo Regional (proyecto FIS No. 01/0071); Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar Y Comunitaria (semFYC); and Unidad de Servicio a la Gestión Sanitaria, Novartis Farmacéutica S.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodgkin K. Diagnostic vocabulary for primary care. J Fam Pract. 1979;8(1):129–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ. 1996;313 (7064):1062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littlejohns P, Wyatt JC, Garvican L. Evaluating computerised health information systems: hard lessons still to be learnt. BMJ. 2003;326(7394):860–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson JW, German PS, Weiss R, Skinner EA, Bowes F 3rd. Health science information management and continuing education of physicians. A survey of U.S. primary care practitioners and their opinion leaders. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(2):151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(4):596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, et al. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999;319(7206): 358–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrie AR, Ward AM. Questioning behaviour in general practice: a pragmatic study. BMJ. 1997;315(7121):1512–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ely JW, Burch RJ, Vinson DC. The information needs of family physicians: case-specific clinical questions. J Fam Pract. 1992;35(3): 265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stinson ER, Mueller DA. Survey of health professionals’ information habits and needs. Conducted through personal interviews. JAMA. 1980;243(2):140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman PN, Ash J, Wykoff L. Can primary care physicians’ questions be answered using the medical journal literature? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994;82(2):140–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambliss ML, Conley J. Answering clinical questions. J Fam Pract. 1996;43(2):140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Gorman PN, et al. A taxonomy of generic clinical questions: classification study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):429–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, et al. Obstacles to answering doctors’ questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002;324(7339):710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Chambliss ML, Ebell MH, Rosenbaum ME. Answering physicians’ clinical questions: obstacles and potential solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(2):217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett NL, Casebeer LL, Kristofco R, Collins BC. Family physicians’ information seeking behaviors: a survey comparison with other specialties. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink-Muinen A, Bensing J, De Maeseneer J. Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ. 2002;325(7362):472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson A, Childs S. The relationship between consultation length, process and outcomes in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(485):1012–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman T. Using video-recorded consultations for research in primary care: advantages and limitations. Fam Pract. 2000;17(5):422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coumou HC, Meijman FJ. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(1):55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soler JK, Okkes IM. Sick leave certification: an unwelcome administrative burden for the family doctor? The role of sickness certification in Maltese family practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004;10(2):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grandage KK, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. When less is more: a practical approach to searching for evidence-based answers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002;90(3):298–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alper BS, White DS, Ge B. Physicians answer more clinical questions and change clinical decisions more often with synthesized evidence: a randomized trial in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawes M, Sampson U. Knowledge management in clinical practice: a systematic review of information seeking behavior in physicians. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]