Abstract

The cleavage stimulation factor (CstF) is essential for the first step of poly(A) tail formation at the 3' ends of mRNAs. This heterotrimeric complex is built around the 77-kDa protein bridging both CstF-64 and CstF-50 subunits. We have solved the crystal structure of the 77-kDa protein from Encephalitozoon cuniculi at a resolution of 2 Å. The structure folds around 11 Half-a-TPR repeats defining two domains. The crystal structure reveals a tight homodimer exposing phylogenetically conserved areas for interaction with protein partners. Mapping experiments identify the C-terminal region of Rna14p, the yeast counterpart of CstF-77, as the docking domain for Rna15p, the yeast CstF-64 homologue.

INTRODUCTION

mRNA 3′ end maturation is part of a general scheme of pre-mRNA processing comprising 5′-capping and intron-splicing. All these maturation events are essential and tightly coupled and controlled for proper gene expression (1,2). mRNAs poly(A) tails are produced by cleavage and polyadenylation of the pre-mRNA molecule (3). Occurring co-transcriptionally, pre-mRNA 3′-end processing is critical for termination of transcription and mRNA export (1). As opposed to the striking divergence of the cis-acting sequence elements that direct cleavage and polyadenylation, the protein components of the pre-mRNA 3′-end processing complexes are quite well conserved from yeast to mammals. In metazoans, cleavage of the precursor requires the trimeric complex cleavage stimulation factor (CstF) and the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor CPSF. Both of them are crucial to identify during a preliminary step the precise sequence elements on the precursor where cleavage, and hence polyadenylation thereafter, would occur (4). Additional factors are then recruited, CF Im, CF IIm, and the poly(A) polymerase PAP, to stabilize the initial interaction and trigger the processing. A network of physical interactions between subunits of the 3′-end processing machinery and the transcription apparatus has been partially drawn that could explain to some extent how processing, transcription termination and export can be regulated. Many interactions between the pre-mRNA 3′ end processing factors have been reported for the human, Drosophila and yeast systems.

CstF is a multimeric complex essential for the reaction to occur. In human and Drosophila, CstF is formed of CstF-50, CstF-64 and CstF-77 (4). The more likely yeast counterparts are respectively, Pfs2p, Rna15p and Rna14p (5,6). CstF-50 exhibits characteristic WD repeats which are involved in the assembly of multi-protein factors (7). CstF-64 bears an RRM-type RNA-binding domain required for the recognition of U/GU-rich elements located downstream of the poly(A) site (8–10). It plays a key role in the choice of the cleavage site and hence, in the efficiency of the reaction (11,12). CstF-77 is critical for the assembly of the complex, bridging both CstF64 and CstF-50. It is the prototypical Half-a- TPR-containing (HAT) protein as defined by Preker and Keller (13). Moreover, CstF-77 is located at the crossroads in the network of interactions with other 3′-end formation factors such as CPSF and CF IIm. It connects CstF to CPSF-160 and hPcf11 (14). Mutations in Rna15p and Rna14p not only impair formation of the mRNA 3′-ends but also prevent RNA polymerase II to terminate properly (15,16). Export of the imperfect transcripts is affected and, as a consequence, they are subsequently degraded (17–21). A growing number of structural studies have shed light on how the catalytic reactions and the regulation may occur in this complex biological machinery (22–27). The structure of protein interacting domains and protein–RNA complexes have been also reported (26,28–30). Many basic questions are still open such as the exact subunit composition of some specific complexes. In this study, we report the crystal structure of the core subunit of the CstF complex at 2.0-Å resolution. CstF-77 is built around 11 HAT repeats that self-assemble to form a tight homodimer. The complex has an overall V-shape with large dimensions. Apart from the conserved dimerization interface, several other phylogenetically conserved areas appear at the surface of the complex that may well represent platforms for the association with other protein partners. Mapping experiments performed with the yeast orthologues of Cstf-77 and CstF-64 allows the identification of the docking domain of Rna15p onto Rna14p.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Protein expression, purification and crystallization

The full-length CstF-77 protein of Encephalitozoon cuniculi (31) was cloned into a modified pET-15b overexpression plasmid allowing the production of an N-terminally His-tagged fusion protein (32). Purification was carried out after cell lysis by centrifugation at 4°C for 1 h at 50 000g. The supernatant was incubated in batch with an affinity resin (Talon) and the eluate was loaded on a HiQ-Sepharose (Pharmacia). The protein was concentrated to 30 mg/ml in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 100 mM NaCl. Crystallization of the sample was carried out at room temperature using sitting-drop vapour diffusion by mixing 1 volume of protein solution with 1 volume of 10% PEG 2000 MME, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 70 mM calcium acetate of reservoir solution (Nextal). Crystals were directly cryoprotected in a solution of 25% Methyl-2 Pentane-Diol, 10% PEG 2000% MME, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 70 mM calcium acetate and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection. Data were processed with XDS (33). Data collection and phasing statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data phasing and refinement statistics

| Native 1 | Se-Met (peak) | |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 44.5 148.4 91.0 | 44.7 149.9 91.6 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0 92.2 90.0 | 90.0 91.0 90.0 |

| X-ray source | ESRF-ID14-2 | ESRF-BM-14 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9340 | 0.978 (peak) |

| Resolution (Å) | 20–2.0 | 25–2.55 |

| Total measurements | 291 014 (44 787)a | 290 548 (44 218)b |

| Unique reflections | 77 953 (12 258)a | 74 414 (11 392)b |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (3.65)a | 3.9 (3.8)b |

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (95.1)a | 97.6 (95.0)b |

| Rsym (%) | 7.7 (38.6)a | 7.0 (34.3)b |

| I/σ | 15.17 (3.69)a | 17.8 (4.2)b |

| FOM (acentric) | 0.34 | |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Protein residues | 800 | |

| Water molecules | 325 | |

| Rwork (%) | 22.5 | |

| Rfree (%) | 27.9 | |

| φψ Most favoured (%) | 96 | |

| φψ Additionally allowed (%) | 3.2 |

aStatistics for high resolution bin (2.0–2.12 Å) are indicated in parentheses.

bHigh resolution bin (2.55–2.7 Å) are indicated in parentheses.

Structure solution

The crystal structure of full-length E. cuniculi CstF-77 (1–493) was solved to 2.55 Å using phases determined from a SAD (single anomalous dispersion) dataset on a crystal grown by macroseeding with selenomethionine-substituted protein. Thirty-six Se-sites were located using SHELXD (34) and phases were calculated with SHARP (35). An initial model was automatically built using Arp/Warp (36). This initial model was used as a template for molecular replacement against the best native dataset. The model was improved by manual docking of residues and missing portions of the molecules with Coot (37). Model refinement was achieved with REFMAC5 (38). The final model was refined to a resolution of 2.0 Å with a working and free R-values of 27.9 and 22.5%, respectively, and good stereochemistry (Table 1). Strikingly, the final model contains two monomers arranged into a non-crystallographic homodimer, in which short stretches of residues at the N- and C-terminal ends are missing (Figure 1). The final model consists of residues 12 to 465 with the exception of three short loops (62–65, 271–280 and 427–429). Chain B is less defined and consists of residues 12 to 454 with the exception of residues (60–68), (92–111), (131–149), (271–280) and (426–429).

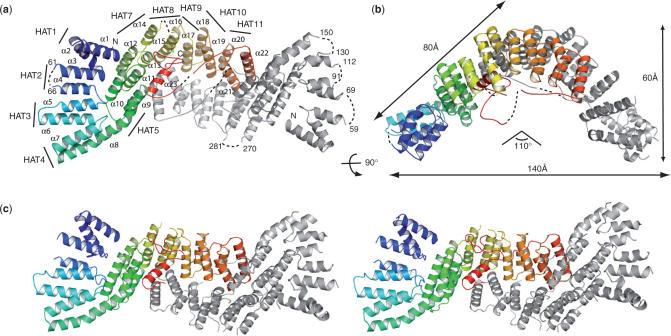

Figure 1.

Structure of CstF-77 homodimer. (a) CstF-77 is built entirely of α-helices belonging to the HAT-repeat family (labelled α1–α23), with the exception of disordered residues (dotted lines). Only one of the two monomers is coloured from blue to red (N to C terminus). The second monomer is shown in grey. HAT repeats are indicated. (b) Schematic representation of CstF-77 homodimer. The two views are related by a 90° rotation as indicated. (c) Stereoview of CstF-77 homodimer.

Surface conservation calculation

Surface conservation has been calculated with Consurf server with a sequence alignment including Homo sapiens, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, Drosophila melanogaster, Xenopus laevis, Caenorhabditis elegans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Arabidopsos thaliana sequences (39).

Pull-down assays

The Rna14p constructs (1–677), (1–593) and (589–677) were amplified by PCR from yeast genomic DNA and cloned into the NdeI and BamHI site of a modified pET-15b vector allowing expression of a protein fused to a His-tag at its N-terminus. The full-length Rna15p protein was amplified from the yeast genome and cloned into the NdeI–XhoI a modified pET-28b vector. Co-expression assays where carried out by co-transformation of Rosetta cells. Cells were grown up to an OD600 of 0.6 and cooled down to 15°C. Overexpression was induced by an overnight incubation with 1 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and sonicated. A crude extract sample was saved at this point and boiled in Laemmli buffer (T, total extract). After 10 min centrifugation at 4°C, 13 000 r.p.m., the supernatant was incubated for 30 min with His-tag affinity resin and washed three times with 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100. The resin was boiled in Laemmli buffer and the samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE (B, bound). The proteins were transferred on a blot and analysed with polyclonal antibodies directed to Rna15p and Rna14p. Monoclonal antibodies were used to reveal His-tag fused proteins (Amersham, GE Healthcare).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CstF-77 assembles into a homodimer

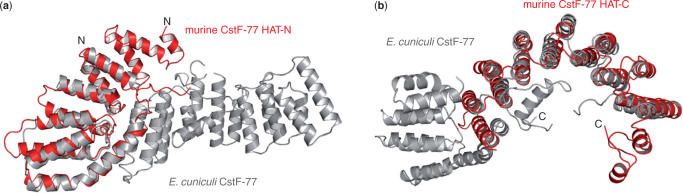

The structure of CstF-77 is entirely α-helical and consists of 23 α-helices arranged in pairs of anti-parallel α-helices forming 11 HAT repeats as described by Preker and Keller (13). It can be divided into two domains, an N-terminal domain containing the first 4 HAT repeats (residues 12 to 151), and a middle domain containing HAT repeats 5 to 12 plus the C-terminal α-helices (residues 162 to 465). Residues 466 to 493 are likely to form an independent domain not seen in our electron density map. Helix 8 provides α-helix B of HAT repeat 4 and α-helix A of HAT repeat 5. It links both domains forming a 145° kink (Figure 1a and Figure 3). The dimer has an overall V-shape with dimensions of 140-Å wide and 60-Å thick, each arm of the V measuring ∼80-Å long (Figure 1b). The 110° angle between both arms is in good agreement with the one measured from electron microscopy pictures obtained with the yeast Rna14p–Rna15p corresponding complex and with the angle measured for the murine CstF-77 complex (40,41). The two CstF-77 monomers are oriented tail-to-tail and interact extensively through their middle domain to form a tight homodimer burying 4000 Å2 of the surface area (Figure 1a and c). The interface between the monomers is provided by the C-terminal α-helix (α-helix 23) of each monomer interacting with HAT-repeat 11 on the one hand. On the other hand, the interaction is built up by HAT-repeats 9 to 11 from one monomer interacting with HAT-repeats 11 to 9 of the opposite monomer and shielded by a well-organized network of water molecules. Superimposition with the murine CstF-77 orthologue HAT-N and HAT-C domains shows limited differences between the two models (Figure 2). Three extra α-helices defining 1.5 HAT repeat at the N-terminus are observed in the murine CstF-77 HAT-N domain in comparison to that of E. cuniculi (Figures 2a and 3)(41). Interestingly, the two last α-helices observed in the murine and the E. cuniculi orthologues have similar orientations but structurally equivalent helices belong to opposite monomers (Figure 2b). In the murine CstF-77, these helices follow the curve formed by the HAT repeats whereas, in the E. cuniculi orthologue, the equivalent helices cross the concave surface defined by HAT repeats 8 to 11 to interact with HAT repeats 6 to 8 (Figure 1). In contrast to murine CstF-77, the prominent pocket observed on the concave surface of the homodimer is likely to be occluded by residues 426 to 430 that could not be placed in our model. Whether this reflects species-specific characteristics has to be tested. Interestingly, homodimerization of the Drosophila CstF-77 homologue, the Su(f) protein, has been proposed to account for the genetic complementation of lethal alleles of the su(f) gene with different domains of the Su(f) protein (42). Similarly, homodimerization of human CstF-77, as well as human CstF-50, were detected by in vitro analysis in a CstF mapping study (43). In yeast, ultracentrifugation analyses of CF IA subunits Rna14p and Rna15p demonstrated a 1:1 stoichiometry of the complex. In addition, these data suggested that the Rna14p–Rna15p heterodimer self-associates via the Rna14p subunit to form a heterotetramer (40). Our model of CstF-77 provides the structural basis for the homodimerization of the protein and its conservation through evolution. Taken together, these data strongly support the idea that CstF functions as a complex comprising two copies of each of its subunits.

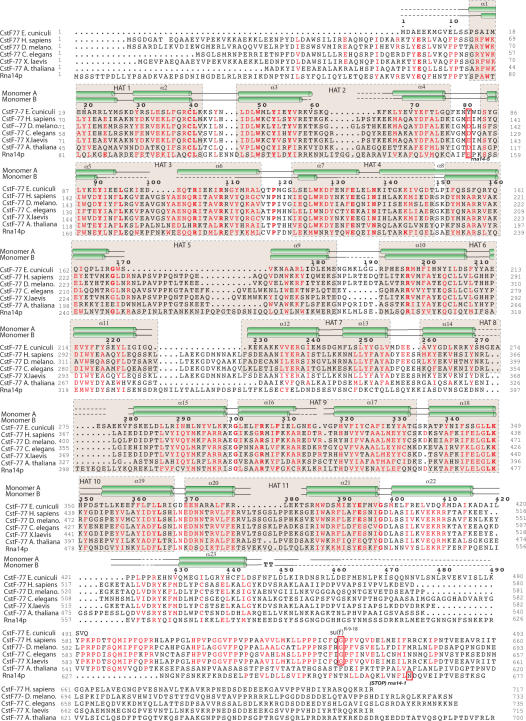

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment CstF-77 homologues. The polypeptide sequence of CstF-77 from E. cuniculi, H. sapiens, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, X. laevis, A. thalina and S. cerevisiae were aligned with PipeAlign (47). Residues are coloured in red when >75% identity is reached. Secondary structures are shown for each monomer on top of the sequences. Dotted lines correspond to sequences for which no interpretable electron density was seen. HAT repeats are boxed in beige. The location of the mutated amino acid in rna14-1, rna14-5 and Drosophila Su(f) R-9-18 mutant are boxed in red.

Figure 2.

Superimposition of murine and E. cuniculi CstF-77 orthologues. The HAT-N (a) and HAT-C domains (b) of the murine CstF-77 (red) were individually superimposed on the N- and middle domain of CstF-77 from E. cuniculi (grey).

CstF-77 homodimer exposes conserved surface

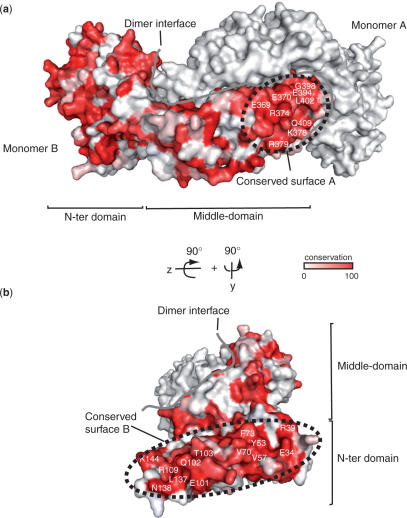

Orthologues of pre-mRNA 3′-end processing factors have been characterized from yeast to human. Functional complementation between Drosophila and human CstF-77 has been demonstrated, with the exception of the C-terminal domain (44). Therefore, the determinants of interaction are likely to be conserved as well. We performed sequence alignment for seven different CstF-77 homologues (Figure 4). Apart from the dimerization interface, two areas at the surface of the complex cluster a number of conserved residues (Figure 4a and b). The first area is located on HAT-repeats 9 to 11 and consists of charged residues (Figure 4a). The tail-to-tail orientation of the two monomers brings into close vicinity the equivalent areas of each molecule leading to a potentially unique extended and conserved surface. The second highly conserved area of the homodimer is located in the N-terminal domain (Figure 4b). The conserved residues of HAT-repeats 1 to 4 are located on the external portion of the dimer. Tyr53, Val57, Val70 and Phe73 cluster into this region and form a hydrophobic patch. Due to the V-shape of the complex and the location of the various conserved regions, the CstF-77 homodimer exposes four highly conserved areas provided by the neighbouring and equivalent areas of HAT repeats 9–11, and by the two independent N-terminal domains of the complex (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CstF-77 homodimer exposes conserved surfaces for interaction with partners. (a) and (b) Residue conservation has been calculated with Consurf from a sequence alignment including CstF-77 homologues. Conservation ranges from white for non-conserved residues, to red for absolutely conserved residues. The two orientations of the complex are related by a 90° rotation in the y- and z-axis. The border of the dimer interface is shown as a solid grey line on both panels.

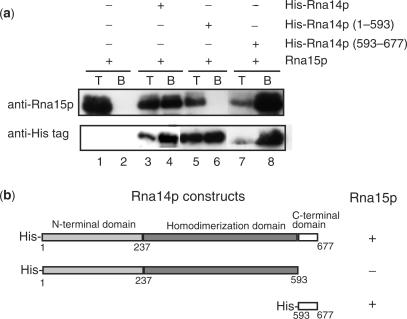

Rna14p C-terminus mediates Rna15p interaction

CstF-77 and its orthologues in yeast and Drosophila are central for CstF complex formation and for the interaction with CPSF. Indeed, Rna14p forms a tight complex with Rna15p and interacts with Pfs2p, Pcf11p and Nab4p/Hrp1p (5,6,40,45). The conserved exposed areas of CstF-77 are likely to provide platforms for the interaction with protein partners. On the basis of our crystal structure, we tested this assumption in pull-down experiments with various deletion constructs of Rna14p co-expressed with Rna15p in Escherichia coli (Figure 5a and b). As expected, full-length His-Rna14p could efficiently pull down Rna15p (Figure 5a, lane 4). However, deletion of the Rna14p C-terminal domain (residues 593 to 677) resulted in the loss of interaction with Rna15p (Figure 5a, lane 6). Co-precipitation of Rna15p with Rna14p C-terminal domain confirmed that this portion of the molecule is sufficient to establish an interaction between the two polypeptides (Figure 5a, lane 8). This domain is important for the function of Rna14p since the shortening of the protein by 16 amino acids at its C-terminus (stop codon at residue 633) observed in the yeast rna14-1 mutant, leads to a defect in 3′ end pre-mRNA processing (46). Altogether, these data suggest that alteration of the interaction between Rna14p and Rna15p is the molecular basis for the loss-of-function phenotype observed in rna14-1 mutant strain. In metazoans, similar interaction have been described for CstF-77 and CstF-64 (41,43). Interestingly, in Drosophila, a single mutation or insertion within the su(f) protein (su(f)R-9-18) impairs its function (42). The C-terminal portion of CstF-77 is highly conserved in metazoans but differs notably from the one in yeast (Figure 3). In summary, these data suggest that the C-terminal Pro-rich portion of CstF-77 and its homologues carries a similar function, even though it is not strictly conserved in sequence from yeast to human. Further analysis is required in order to determine whether this domain has a similar structure in yeast and metazoans.

Figure 5.

Mapping Rna14p–Rna15p interaction. (a) Pull-down experiments were performed between Rna15p and His-tagged Rna14p deletion mutants. Proteins were revealed with polyclonal antibodies to Rna15p and monoclonal antibodies directed against the His-tag. T, total extract; B, bound fraction. (b) Rna14p deletion constructs used in pull-down experiments. ‘+’ and ‘–’ corresponds to interaction and no interaction, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Pr Vivarès, Université Blaise Pascal, Clermond-Ferrand for providing E. cuniculi GB-M1 genome. We would like to thank the staff of ESRF beamlines BM14 and ID14-2. We would like to thank A. Thompson and W. Shepard for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by grants from the INSERM (Avenir program) and the ‘Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer’ (to S.F.) and from the CNRS and ‘La Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale/Fondation BNP-Paribas’ (to L.M.-S.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Avenir program.

Coordinates

The atomic coordinates and structure factor have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession code 2UY1).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosonina E, Kaneko S, Manley JL. Terminating the transcript: breaking up is hard to do. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1050–1056. doi: 10.1101/gad.1431606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proudfoot N. New perspectives on connecting messenger RNA 3′ end formation to transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2004;16:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmonds M. A history of poly A sequences: from formation to factors to function. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 2002;71:285–389. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)71046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takagaki Y, Manley JL, MacDonald CC, Wilusz J, Shenk T. A multisubunit factor, CstF, is required for polyadenylation of mammalian pre-mRNAs. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2112–2120. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minvielle-Sebastia L, Preker PJ, Keller W. RNA14 and RNA15 proteins as components of a yeast pre-mRNA 3′-end processing factor. Science. 1994;266:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.7992054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnacker M, Barabino SM, Preker PJ, Keller W. The WD-repeat protein pfs2p bridges two essential factors within the yeast pre-mRNA 3′-end-processing complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:37–47. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takagaki Y, MacDonald CC, Shenk T, Manley JL. The human 64-kDa polyadenylylation factor contains a ribonucleoprotein-type RNA binding domain and unusual auxiliary motifs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:1403–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald CC, Wilusz J, Shenk T. The 64-kilodalton subunit of the CstF polyadenylation factor binds to pre-mRNAs downstream of the cleavage site and influences cleavage site location. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:6647–6654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takagaki Y, Manley JL. RNA recognition by the human polyadenylation factor CstF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:3907–3914. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyer K, Dandekar T, Keller W. RNA ligands selected by cleavage stimulation factor contain distinct sequence motifs that function as downstream elements in 3′-end processing of pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26769–26779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwalds-Gilbert G, Milcarek C. The binding of a subunit of the general polyadenylation factor cleavage-polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) to polyadenylation sites changes during B cell development. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1995:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takagaki Y, Manley JL. Levels of polyadenylation factor CstF-64 control IgM heavy chain mRNA accumulation and other events associated with B cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preker PJ, Keller W. The HAT helix, a repetitive motif implicated in RNA processing. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:15–16. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murthy KG, Manley JL. The 160-kD subunit of human cleavage-polyadenylation specificity factor coordinates pre-mRNA 3′-end formation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2672–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birse CE, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Lee BA, Keller W, Proudfoot NJ. Coupling termination of transcription to messenger RNA maturation in yeast. Science. 1998;280:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Licatalosi DD, Geiger G, Minet M, Schroeder S, Cilli K, McNeil JB, Bentley DL. Functional interaction of yeast pre-mRNA 3′ end processing factors with RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei EP, Silver PA. Protein and RNA export from the nucleus. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:261–272. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei EP, Silver PA. Intron status and 3′-end formation control cotranscriptional export of mRNA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2761–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.1032902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilleren P, McCarthy T, Rosbash M, Parker R, Jensen TH. Quality control of mRNA 3′-end processing is linked to the nuclear exosome. Nature. 2001;413:538–542. doi: 10.1038/35097110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houseley J, LaCava J, Tollervey D. RNA-quality control by the exosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;7:529–539. doi: 10.1038/nrm1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torchet C, Bousquet-Antonelli C, Milligan L, Thompson E, Kufel J, Tollervey D. Processing of 3′-extended read-through transcripts by the exosome can generate functional mRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bard J, Zhelkovsky AM, Helmling S, Earnest TN, Moore CL, Bohm A. Structure of yeast poly(A) polymerase alone and in complex with 3′-dATP. Science. 2000;289:1346–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin G, Keller W, Doublie S. Crystal structure of mammalian poly(A) polymerase in complex with an analog of ATP. EMBO J. 2000;19:4193–4203. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandel CR, Kaneko S, Zhang H, Gebauer D, Vethantham V, Manley JL, Tong L. Polyadenylation factor CPSF-73 is the pre-mRNA 3′-end-processing endonuclease. Nature. 2006;444:953–956. doi: 10.1038/nature05363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meinhart A, Cramer P. Recognition of RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain by 3′-RNA-processing factors. Nature. 2004;430:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nature02679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble CG, Beuth B, Taylor IA. Structure of a nucleotide-bound Clp1-Pcf11 polyadenylation factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(1):87–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noble CG, Hollingworth D, Martin SR, Ennis-Adeniran V, Smerdon SJ, Kelly G, Taylor IA, Ramos A. Key features of the interaction between Pcf11 CID and RNA polymerase II CTD. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:144–151. doi: 10.1038/nsmb887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez Canadillas JM, Varani G. Recognition of GU-rich polyadenylation regulatory elements by human CstF-64 protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:2821–2830. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Canadillas JM. Grabbing the message: structural basis of mRNA 3′UTR recognition by Hrp1. EMBO J. 2006;25:3167–3178. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu X, Perez-Canadillas JM, Agrawal S, De Baecke J, Cheng H, Varani G, Moore C. The C-terminal domains of vertebrate CstF-64 and its yeast orthologue Rna15 form a new structure critical for mRNA 3′-end processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2101–2115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katinka MD, Duprat S, Cornillot E, Metenier G, Thomarat F, Prensier G, Barbe V, Peyretaillade E, Brottier P, et al. Genome sequence and gene compaction of the eukaryote parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Nature. 2001;414:450–453. doi: 10.1038/35106579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romier C, Ben Jelloul M, Albeck S, Buchwald G, Busso D, Celie PH, Christodoulou E, De Marco V, van Gerwen S, et al. Co-expression of protein complexes in prokaryotic and eukaryotic hosts: experimental procedures, database tracking and case studies. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:1232–1242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. SHARP: a maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement program for the MIR and MAD methods. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrakis A, Harkiolaki M, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS. ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1445–1450. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901014007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landau M, Mayrose I, Rosenberg Y, Glaser F, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noble CG, Walker PA, Calder LJ, Taylor IA. Rna14-Rna15 assembly mediates the RNA-binding capability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cleavage factor IA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3364–3375. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai Y, Auperin TC, Chou CY, Chang GG, Manley JL, Tong L. Crystal structure of murine CstF-77: dimeric association and implications for polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:863–875. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simonelig M, Elliott K, Mitchelson A, O′Hare K. Interallelic complementation at the suppressor of forked locus of Drosophila reveals complementation between suppressor of forked proteins mutated in different regions. Genetics. 1996;142:1225–1235. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.4.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takagaki Y, Manley JL. Complex protein interactions within the human polyadenylation machinery identify a novel component. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1515–1525. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1515-1525.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benoit B, Juge F, Iral F, Audibert A, Simonelig M. Chimeric human CstF-77/Drosophila Suppressor of forked proteins rescue suppressor of forked mutant lethality and mRNA 3′ end processing in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10593–10598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162191899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross S, Moore C. Five subunits are required for reconstitution of the cleavage and polyadenylation activities of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cleavage factor I. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6080–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101046598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rouillard JM, Brendolise C, Lacroute F. Rna14p, a component of the yeast nuclear cleavage/polyadenylation factor I, is also localised in mitochondria. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;262:1103–1112. doi: 10.1007/pl00008653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plewniak F, Bianchetti L, Brelivet Y, Carles A, Chalmel F, Lecompte O, Mochel T, Moulinier L, Muller A, et al. PipeAlign: a new toolkit for protein family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3829–3832. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takagaki Y, Manley JL. A polyadenylation factor subunit is the human homologue of the Drosophila suppressor of forked protein. Nature. 1994;372:471–474. doi: 10.1038/372471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]