Abstract

Human pressure threatens many species and ecosystems, so conservation efforts necessarily prioritize saving them. However, conservation should clearly be proactive wherever possible. In this article, we assess the biodiversity conservation value, and specifically the irreplaceability in terms of species endemism, of those of the planet's ecosystems that remain intact. We find that 24 wilderness areas, all > 1 million hectares, are > 70% intact and have human densities of less than or equal to five people per km2. This wilderness covers 44% of all land but is inhabited by only 3% of people. Given this sparse population, wilderness conservation is cost-effective, especially if ecosystem service value is incorporated. Soberingly, however, most wilderness is not speciose: only 18% of plants and 10% of terrestrial vertebrates are endemic to individual wildernesses, the majority restricted to Amazonia, Congo, New Guinea, the Miombo-Mopane woodlands, and the North American deserts. Global conservation strategy must target these five wildernesses while continuing to prioritize threatened biodiversity hotspots.

The concept of wilderness is ancient. The word itself is derived from the Norse will (uncontrolled) and deor (animal), evolving to its biblical use as “uncultivated” (1). The term began to gain positive connotations through the Romantic and Transcendentalist writers and Hudson River School of landscape painters in the 19th century, fledging into a conservation movement with the writings of Muir, Audubon, and others. The concept first entered a regulatory context in 1929, building up to the U.S. Wilderness Act of 1964, which established the standards for protection of wilderness on federal lands. Countries as diverse as Australia, Canada, Finland, and South Africa now have similar wilderness legislation. A wilderness area is defined in The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Framework for Protected Areas as “a large area of unmodified or slightly modified land and/or sea, retaining its natural character and influence, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural condition” (2). Building from “good news areas” (3) and “major tropical wilderness areas” (4), we now expand the focus of the wilderness concept beyond specific protected areas to inform global conservation strategies.

The units of analysis for this study were based largely on the world's terrestrial ecoregions (5). Where these ecoregions could be combined into broader biogeographic units, such as Amazonia, we aggregated them into single units. To select only ecosystems of global significance, we set a minimum size for inclusion in the analysis as 10,000 km2. As a preliminary assessment of ecoregions for inclusion as wilderness areas, we overlaid a binary classification of human population density data (6) outside of urban areas as greater than and less than five people per km2 (rounding down), retaining only the latter for subsequent analysis (we subsequently also identified areas with approximately one person or less per km2). We then conducted an extensive literature search and contacted >200 specialists on these potential wilderness areas, compiling data on intactness, biodiversity, human populations, threats, and existing conservation initiatives. We used intactness (7) as a further criterion for inclusion, stipulating that an area must retain at least 70% of its historical habitat extent (500 years ago) to be considered a wilderness area. These data are less precise than the other data used here, with sources ranging from detailed remote sensing assessments through to the opinion of regional specialists, and so we use only one significant figure for intactness throughout.

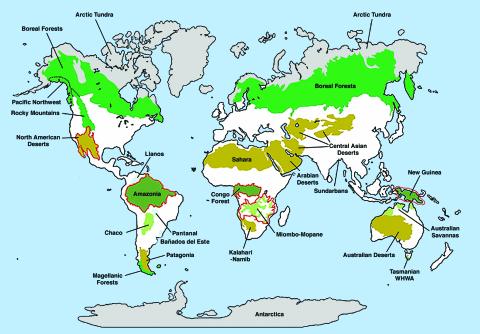

In total, this analysis identified 24 wilderness areas (Fig. 1). These fall into nine terrestrial biome types (8): Tropical Humid Forest (three areas, 12% of total area); Tropical Dry Forests and Tropical Grasslands (three areas, 4% of total area); Warm Deserts/Semideserts and Cold-Winter Deserts (seven areas, 30% of total area); Mixed Mountain Systems, Temperate Rain-forests, and Temperate Needleleaf Forests (five areas, 23% of total area); and Tundra Communities and Arctic Desert (two areas, 30% of total area); plus four relatively small wetland wildernesses (1% of total area). Six additional regions (the Appalachians, the European mountains, the Sudd swamp, the Serengeti, the Brazilian Caatinga, and the Peruvian and Chilean coastal deserts) came close to but failed to meet the thresholds. The total historical area of the 24 wildernesses was 76 million km2, 52% of the Earth's land area, of which 65 million km2 remains intact, covering 44% of the planet (Table 1, and see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). The total human population of these areas is 204 million (3% of the global total), which is reduced to 83 million (1.4%) when urban areas are excluded (Table 1 and see Table 3), giving an average rural population density of 1.1 people per km2.

Fig. 1.

Overall map showing wilderness areas, human population density less than or equal to five people per km2, with biomes shaded, and the five high-biodiversity wilderness areas outlined in red.

Table 1. Extents of the 24 wilderness areas, their human populations, and their levels of protection.

|

Population†

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biome and wilderness | Area,* km2 | Intact,* % | Total | Minus urban | People per km2† | Protected areas,‡ % |

| Tropical humid forest | ||||||

| Amazonia | 6,683,926 | 80 | 21,430,115 | 7,355,126 | 1.1 | 8.3 |

| Congo forest | 1,725,221 | 70 | 16,000,000 | 10,000,000 | 5.8 | 8.1 |

| New Guinea | 828,818 | 70 | 6,000,000 | 4,197,200 | 5.1 | 11 |

| Tropical dry forests and grasslands | ||||||

| Chaco | 996,600 | 70 | 2,810,000 | 648,693 | 0.65 | 7.5 |

| Miombo-Mopane | 1,176,000 | 90 | 5,839,000 | 3,816,000 | 3.2 | 36 |

| Australian savannas | 585,239 | 100 | 60,730 | 24,188 | 0.041 | 11 |

| Mixed mountain, temperate rain, and temperate needleleaf forest | ||||||

| Rocky Mountains | 570,500 | 70 | 1,574,986 | 1,035,174 | 1.8 | 17 |

| Pacific Northwest | 315,000 | 80 | 770,000 | 597,095 | 1.9 | 48 |

| Magellanic forests | 147,200 | 100 | 253,264 | 34,501 | 0.23 | 72 |

| Tasmanian WHWA | 13,836 | 90 | 8 | 8 | 0.000058 | 100 |

| Boreal forests | 16,179,500 | 80 | 30,337,925 | 15,438,546 | 0.95 | 3.8 |

| Wetland | ||||||

| Llanos | 451,474 | 80 | 4,444,243 | 1,065,956 | 2.4 | 15 |

| Pantanal | 210,000 | 80 | 1,125,200 | 81,200 | 0.38 | 2.7 |

| Bañados del Este | 38,500 | 80 | 200,000 | 40,000 | 1.0 | 2.8 |

| Sundarbans | 10,000 | 80 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 0.30 | 31 |

| Warm and cold-winter deserts | ||||||

| North American deserts | 1,416,134 | 80 | 15,348,342 | 4,509,403 | 3.2 | 23 |

| Patagonia | 550,400 | 70 | 800,000 | 200,000 | 0.36 | 4.1 |

| Sahara | 7,780,544 | 90 | 35,187,620 | 10,273,595 | 1.3 | 2.8 |

| Kalahari-Namib | 714,700 | 80 | 1,422,700 | 425,900 | 0.60 | 25 |

| Arabian deserts | 3,250,000 | 90 | 47,000,000 | 15,000,000 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

| Central Asian deserts | 5,943,000 | 80 | 9,000,000 | 5,500,000 | 0.93 | 2.8 |

| Australian deserts | 3,572,209 | 90 | 400,000 | 285,000 | 0.080 | 9.4 |

| Tundra | ||||||

| Arctic tundra | 8,850,000 | 90 | 4,288,613 | 2,385,713 | 0.27 | 20 |

| Antarctic | 13,900,000 | 100 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.000072 | 0.025 |

| Total | 75,908,801 | 90 | 204,296,746 | 82,917,298 | 1.1 | 7.5 |

WHWA, World Heritage Wilderness Area.

Area of each of wilderness area and percentage intactness (one significant figure). Areas must exceed 10,000 km2 and 70% intactness to qualify as wildernesses.

Human population, human population outside of urban areas, and human population density (two significant figures) of each wilderness area.

Percentage (two significant figures) of each wilderness area under protected area status (IUCN categories I-IV).

Considering only those 16 wilderness areas with rural human population densities of less than approximately one person per km2, the results are even more striking. Together, these areas covered 66 million km2 (45% of the land's surface), of which ∼90% remains intact, accounting for 57 million km2 (39% of the land's surface), an area equivalent to the world's six largest countries combined. A third of this area is under permanent ice, making habitation impossible; in total, this vast area holds just 43 million people, or 0.7% of Earth's human population.

This study provides an assessment of the biodiversity value of remaining wilderness areas. About 55,000 vascular plant species (18% of the global total) and 2,800 terrestrial vertebrate species (10%) are endemic to the wilderness areas (Table 2, and see Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The disparity between the plant and the vertebrate percentages is probably explained by the much smaller mean range size of plants (9). However, even for plants, and even given that many wilderness areas are poorly studied (10), this percentage is clearly far lower than would be expected were endemic species distributed across ecoregions in proportion to land area. Further, the vast majority of these species are concentrated into just five high-biodiversity wilderness areas: Amazonia, the Congo forests of Central Africa, New Guinea, the Miombo-Mopane woodlands of Southern Africa (including the Okavango Delta), and the North American desert complex of northern Mexico and the southwestern U.S. The intact portion of these five wildernesses covers 8,981,000 km2 (76% of their original extent), 6.1% of the planet's land area. Between them they hold >51,000 vascular plants (17% of the global total) and 2,300 terrestrial vertebrates (8% of the global total) as endemics. Even for these five areas, the concentration of biodiversity pales in comparison to that of the 25 biodiversity hotspots (11), which hold nearly 3 times as many endemics in an area one-fourth as large.

Table 2. Biodiversity of the 24 wilderness areas, in terms of species richness (R) and endemism (E) for vascular plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians.

|

Plants

|

Mammals

|

Birds

|

Reptiles

|

Amphibians

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biome and wilderness | R | E | R | E | R | E | R | E | R | E |

| Tropical humid forest | ||||||||||

| Amazonia | 40,000 | 30,000 | 425 | 172 | 1,300 | 263 | 371 | 260 | 427 | 366 |

| Congo forest | 9,750 | 3,300 | 275 | 39 | 698 | 8 | 142 | 15 | 139 | 28 |

| New Guinea | 17,000 | 10,200 | 233 | 146 | 650 | 334 | 275 | 159 | 237 | 215 |

| Tropical dry forests and grasslands | ||||||||||

| Chaco | 2,000 | 90 | 150 | 12 | 500 | 7 | 117 | 17 | 60 | 8 |

| Miombo—Mopane | 8,500 | 4,600 | 336 | 14 | 938 | 54 | 301 | 69 | 138 | 33 |

| Australian savannas | 3,176 | 594 | 219 | 13 | 343 | 4 | 214 | 66 | 44 | 15 |

| Mixed mountain, temperate rain, and temperate needleleaf forest | ||||||||||

| Rocky Mountains | 1,414 | 22 | 92 | 1 | 264 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 2 |

| Pacific Northwest | 1,088 | 7 | .80 | 3 | 227 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Magellanic forests | 450 | 35 | 42 | 2 | 121 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 2 |

| Tasmanian WHWA | 924 | 62 | 32 | 2 | 121 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| Boreal forests | 2,000 | 200 | 196 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 36 | 0 |

| Wetland | ||||||||||

| Llanos | 3,424 | 40 | 198 | 3 | 475 | 1 | 107 | 1 | 48 | 6 |

| Pantanal | 3,500 | 0 | 124 | 0 | 423 | 0 | 177 | 0 | 41 | 0 |

| Bañados del Este | 1,300 | 5 | 79 | 0 | 311 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| Sundarbans | 334 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Warm and cold-winter deserts | ||||||||||

| North American deserts | 5,740 | 3,240 | 197 | 32 | 248 | 4 | 225 | 93 | 53 | 7 |

| Patagonia | 1,221 | 296 | 60 | 4 | 211 | 10 | 47 | 19 | 12 | 5 |

| Sahara | 1,600 | 188 | 124 | 14 | 360 | 0 | 82 | 7 | 12 | 0 |

| Kalahari—Namib | 1,200 | 80 | 103 | 2 | 341 | 3 | 105 | 18 | 19 | 0 |

| Arabian deserts | 3,300 | 340 | 102 | 10 | 213 | 2 | 108 | 52 | 8 | 4 |

| Central Asian deserts | 2,500 | 750 | 82 | 27 | 90 | 6 | 100 | 20 | 6 | 0 |

| Australian deserts | 3,000 | 150 | 98 | 14 | 346 | 3 | 340 | 83 | 34 | 5 |

| Tundra | ||||||||||

| Arctic tundra | 1,125 | 100 | 115 | 10 | 379 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Antarctic | 60 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | — | 54,299 | — | 520 | — | 701 | — | 882 | — | 697 |

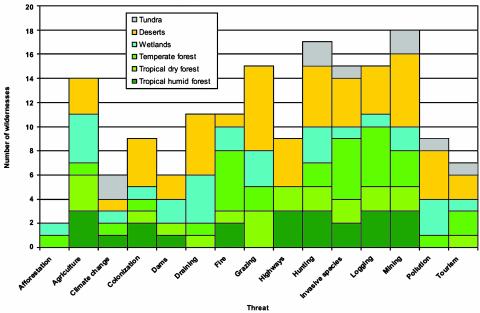

Of the 76 million km2 covered by the wilderness areas, <6 million km2 (7%) fall within protected areas of the IUCN categories I-IV. Coverage varies enormously (Tables 1 and 3), from minimal (e.g., Antarctica, 0.025%) to total (Tasmanian World Heritage Wilderness Area, 100%) but is generally inadequate given the threats facing these regions. Of 15 nonmutually exclusive threat categories (Fig. 2), agriculture, grazing, hunting, invasive species, logging, and mining are the most pervasive, each affecting more than half of the wilderness areas. Disconcertingly, all but grazing affect four or more of the high-biodiversity wilderness areas. Several threats are concentrated into particular biome types: logging and fire disproportionately affect forest; grazing, drainage, pollution, and dams disproportionately affect wetlands and deserts. Although these threats are pervasive in scope, as demonstrated by the presence of DDT residues in Adelie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae), for example (12), they are currently minor in severity compared with those facing the rest of the planet (13).

Fig. 2.

Threats to the wilderness areas (categories are not mutually exclusive), shaded by biome.

Our results clearly depend on the ecoregions on which our units of analysis are based, which, although not universally accepted, constitute the most up-to-date global land classification available (14). The only global assessments of wilderness to date have used the alternative approach of measuring continuous variables: infrastructure across 4,000-km2 cells (15); or a combined score of population, urbanization, transport networks, and power infrastructure (16). However, analysis of such continuous variables requires use of weighted scoring no less arbitrary than the threshold approach used here. Further, reliance on population data and infrastructure surrogates such nocturnal lights (17) will inevitably miss the large areas heavily transformed by agriculture and grazing (18). Nevertheless, both of these studies (15, 16) produced wilderness maps remarkably similar to ours, although with lower overall areas of wilderness because of their use of more severe thresholds, for example, <1 person per km2 (16). The earlier study (15) was subsequently refined by overlaying habitat data, which suggested that only 22% of the planet's original forest cover remains as undisturbed “frontier forests” (19), including much of the eight forest wildernesses identified by us. Further, synthetic studies suggest that >40% of net primary productivity is appropriated by humans (20, 21), which is also broadly consistent with our finding that just under half of the planet remains wild.

What other biases might influence our results? Our definition of intactness as the proportion of historical habitat remaining clearly gives a temporal threshold, in the same way as ecoregions frame the study with spatial thresholds. Much of the world was heavily modified by prehistoric human activity through the Pleistocene (22). This is most notable, perhaps, in Australia, where the extent of anthropogenic megafaunal extinction was such that none of the continent can be considered in any way “pristine” (23). Another obvious important limitation is our concentration in the terrestrial realm, although human appropriation of 60% of freshwater (24) and 35% of ocean shelf productivity (25) suggests that the intact proportion of these realms is comparable to that of land.

With the exception of the five high-biodiversity wilderness areas, this study reveals that the targets of biodiversity conservation and of wilderness conservation are generally different (26). Although they surely hold the bulk of the planet's biomass and also the last remaining intact megafaunal assemblages, the wilderness areas hold many fewer species than expected. This is unsurprising, given the correlation between human population density and biodiversity (27). However, these areas are of great importance for numerous other reasons (28). The ecosystem services they provide have enormous value (29), for example, through hydrological control, nitrogen fixation, pollination, and carbon sequestration, in addition to providing destinations for ecotourism and adventure tourism. The wilderness areas serve as valuable controls against which to measure the health of the planet (30). The coincidence between areas of biological and cultural diversity, at least in Africa (31), also means that the high-biodiversity wilderness areas provide the last strongholds for many of the world's languages (32). Finally, there are strong aesthetic, moral, and spiritual values of wilderness, permeating all cultures and religions, and providing a firm imperative for its conservation (33).

The value of wilderness can be further put into perspective if the cost of its conservation is considered. The low population densities of wilderness areas suggest that land values and hence costs of endowing conservation and management will be relatively inexpensive, maybe $10/hectare in the high-biodiversity wilderness areas, for example (34). Thus, these five areas could be protected with an investment of ∼$10 billion. To conserve wilderness globally might cost 5 times this, given that the rest of the planet's wilderness is 6 times larger but less productive for agriculture, and so presumably cheaper per hectare. Estimated globally, the cost-to-benefit ratio of conserving wild nature is estimated as 1:100 (35). Given the opportunity costs of not undertaking conservation (and hence investing in marginal development) we suspect that this disparity will increase markedly in the wilderness areas. Conservation of the remaining wild half of the planet, through an integrated strategy of protection, zoning, and carefully implemented best practices in industry and agriculture, would be a strikingly good bargain.

Of course, this is not to suggest that the wilderness areas are terra nullius, empty lands (36), but rather that they lie at one end of a continuum of human impact (13). Further, the unfortunate coincidence among biodiversity, threat, and human populations (37) means that most conservation should remain concentrated at the other end of this continuum, in the hotspots of biodiversity (11). Thus, the low cost and great value to humanity of the world's remaining wildernesses better justify their conservation than does their biodiversity. However, efficient global biodiversity conservation should focus on a two-pronged strategy targeting the 6.1% of the land's surface covered by the five high-biodiversity wilderness areas as well as the 1.4% covered by the hotspots. Such a strategy could conserve more than one-sixth of species as endemic to the high-biodiversity wildernesses and more than one-third to the hotspots, and the biodiversity conservation community would be wise to allocate their scarce resources accordingly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Aguiar, T. S. B. Akre, T. Allnutt, S. Andrew, F. Arjona, P. Arrata, C. Aveling, the late J. M. Ayres, M. I. Bakarr, R. Barongi, B. Beehler, A. E. Bowland, I. A. Bowles, D. Broadley, N. H. Brooks, B. Burnham, K. Burnham, A. Búrquez, J. Cannon, J. M. Cardoso da Silva, G. Castro, H. F. Castro, R. Cavalcanti, G. Ceballos, S. Charlton, E. Chidumayo, S. Chown, C. Christ, J. Chun, D. Connell, G. Crowley, J. D'Amico, L. Dávalos, M. Diaz, C. I. Dymond, F. El-Baz, M. Evans, E. Ezcurra, K. Falk, L. Famolare, J. M. Fay, A. L. Flores, A. Forsyth, S. M. Fritz, P. Frost, S. Garnett, B. Goettsch, H. González, A. Grill, M. Guerin-McManus, R. Ham, J. Hanks, G. Harris, M. Harris, J. A. Hart, H. M. Hernández, C. Hill, C. Hutchinson, V. H. Inchausty, N. Jackson, D. Johnson, R. Kays, M. M. H. Khan, P. J. Kristensen, G. R. Kula, T. E. Lacher, Jr., J. Lamoreux, O. Langrand, N. P. Lapham, G. Leach, F. López, R. F. Ferreira Lourival, R. Lovich, J. E. Lovich, J. A. Lucena, D. Maestro, I. L. Magole, D. Mallon, S. A. J. Malone, L. Manler, M. A. Mares, P. Marquet, V. G. Martin, R. B. Mast, A. J. Meier, A. Mekler, E. Mellink, F. Miranda, J. C. Mittermeier, J. Morrison, D. M. Muchoney, J. Neldner, R. Nelson, A. J. Noss, E. M. Outlaw, E. Palacios, H. Peat, E. Peters, S. Pandya, J. Pickering, R. Pinto, N. Platnick, C. F. Ponce, L. Poston, G. T. Prickett, E. Rachkovskaya, G. R. Rahr III, R. Rice, J. A. Rivas, P. Robles Gil, R. Roca, J. V. Rodríguez, K. Ross, J. V. Rueda Almonacid, C. Santoro, J. Schipper, R. Schmidt, B. d'Silva, J. G. Singh, L. L. Sørensen, V. G. Standen, A. Stattersfield, G. S. Stone, H. Strand, C. Sugal, J. Supriatna, J. B. Thomsen, J. Timberlake, A. Tjon Sie Fat, M. Totten, W. Udenhout, P. Uetz, M. van Roosmalen, N. A. Waldron, K. Walker, F. Warinwa, L. J. T. White, I. Whyte, P. Winter, J. Woinarski, K. Yatskievych, H. Zeballos, and especially C. Gascon, S. D. Nash, A. B. Rylands, S. Stuart, R. Waller, and Agrupación Sierra Madre. This study was funded by the Mexican cement company CEMEX, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through Conservation International's Global Conservation Fund, the Moore Family Foundation through the Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, and Shawn Concannon.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Nash, R. F. (1967) Wilderness and the American Mind (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT).

- 2.World Conservation Union (1994) Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories (World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland).

- 3.Myers, N. (1988) Environmentalist 8, 187-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittermeier, R. A., Myers, N., Thomsen, J. B., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Olivieri, S. (1998) Conserv. Biol. 12, 516-520. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., D'Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H., Morrison, J. C., et al. (2001) Bioscience 51, 933-938. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for International Earth Science Information Network, International Food Policy Research Institute, and World Resources Institute (2000) Gridded Population of the World (GPW) (Center for International Earth Science Information Network, New York), Version 2.

- 7.Hannah, L., Carr, J. L. & Lankerani, A. (1995) Biodivers. Conserv. 4, 128-155. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udvardy, M. D. F. (1975) A Classification of the Biogeographical Provinces of the World (World Conservation Union, Morges, Switzerland).

- 9.Rodrigues, A. S. L. & Gaston, K. J. (2001) Ecol. Lett. 4, 602-609. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prance, G. T., Beentje, H., Dransfield, J. & Johns, R. (2000) Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 87, 67-71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. (2000) Nature 403, 853-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sladen, W. J. L., Menzie, C. M. & Reichel, W. L. (1966) Nature 210, 670-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesslie, R. G. & Taylor, S. G. (1985) Biol. Conserv. 32, 309-333. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wikramanayake, E., Dinerstein, E., Loucks, C., Olson, D., Morrison, J., Lamoreux, J., McKnight, M. & Hedao, P. (2002) Conserv. Biol. 16, 238-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCloskey, M. J. & Spalding, H. (1989) Ambio 8, 221-227. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanderson, E. W., Jaiteh, M., Levy, M. A., Redford, K. H., Wannebo, A. V. & Woolmer, G. (2002) Bioscience 52, 891-904. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobson, J. E., Bright, E. A., Coleman, P. R., Durfee, R. C. & Worley, B. A. (2000) Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 66, 849-858. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J. & Melillo, J. M. (1997) Science 277, 494-499. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant, D., Nielsen, D. & Tangley, L. (1997) The Last Frontier Forests: Ecosystems and Economies on the Edge (World Resources Inst., Washington, DC).

- 20.Vitousek, P. M., Ehrlich, P. R., Ehrlich, A. H. & Matson, P. A. (1986) Bioscience 36, 368-373. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojstaczer, S., Sterling, S. M. & Moore, N. J. (2001) Science 294, 2549-2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, P. & Klein, R. (1984) Quaternary Extinctions, a Prehistoric Revolution (Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson).

- 23.Flannery, T. (1994) The Future Eaters (George Braziller, New York).

- 24.Postel, S. L., Daily, G. C. & Ehrlich, P. R. (1996) Science 271, 785-788. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauly, D. & Christensen, V. (1995) Nature 374, 255-257. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar, S. (1999) Bioscience 49, 405-411. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balmford, A., Moore, J. L., Brooks, T., Burgess, N., Hansen, L. A., Williams, P. & Rahbek, C. (2001) Science 291, 2616-2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Callicott, J. B. & Nelson, M. P. (1998) The Great New Wilderness Debate (Univ. of Georgia Press, Atlanta).

- 29.Daily, G. (1997) Nature's Services, Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems (Island, Washington, DC).

- 30.da Fonseca, G. A. B., Gascon, C., Steininger, M. K., Brooks, T., Mittermeier, R. A. & Lacher, T. E., Jr. (2002) Science 295, 1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore, J. L., Manne, L., Brooks, T., Burgess, N. D., Davies, R., Rahbek, C., Williams, P. & Balmford, A. (2002) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 169, 1645-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimes, B. F. (1996) Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Dallas).

- 33.Cronon, W. (1996) Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (Norton, New York).

- 34.Pimm, S. L., Ayres, M., Balmford, A., Branch, G., Brandon, K., Brooks, T., Bustamante, R., Costanza, R., Cowling, R., Curran, L. M., et al. (2001) Science 293, 2207-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balmford, A., Bruner, A., Cooper, P., Costanza, R., Farber, S., Green, R. E., Jenkins, M., Jefferiss, P., Jessamy, V., Madden, J., et al. (2002) Science 297, 950-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langton, M. (1998) Burning Questions: Emerging Environmental Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Northern Australia (Northern Territory Univ., Darwin, Australia).

- 37.Cincotta, R. P., Wisnewski, J. & Engelman, R. (2000) Nature 404, 990-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.