Abstract

Propagation of R5 strains of HIV-1 on CD4 lymphocytes and macrophages requires expression of the CCR5 coreceptor on the cell surface. Individuals lacking CCR5 (CCR5Δ32 homozygous genotype) are phenotypically normal and resistant to infection with HIV-1. CCR5 expression on lymphocytes depends on signaling through the IL-2 receptor. By FACS analysis we demonstrate that rapamycin (RAPA), a drug that disrupts IL-2 receptor signaling, reduces CCR5 surface expression on T cells at concentrations as low as 1 nM. In addition, lower concentrations of RAPA (0.01 nM) were sufficient to reduce CCR5 surface expression on maturing monocytes. PCR analysis on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) showed that RAPA interfered with CCR5 expression at the transcriptional level. Reduced expression of CCR5 on PBMCs cultured in the presence of RAPA was associated with increased extracellular levels of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β. In infectivity assays, RAPA suppressed the replication of R5 strains of HIV-1 both in PBMC and macrophage cultures. In total PBMC cultures, RAPA-mediated inhibition of CCR5-using strains of HIV-1 occurred at 0.01 nM, a concentration of drug that is ∼103 times lower than therapeutic through levels of drug in renal transplant recipients. In addition, RAPA enhanced the antiviral activity of the CCR5 antagonist TAK-779. These results suggest that low concentrations of RAPA may have a role in both the treatment and prevention of HIV-1 infection.

The importance of CCR5 for initial transmission of HIV-1 is highlighted by the fact that individuals lacking expression of CCR5 (the CCR5-Δ32 homozygous genotype) are usually resistant to infection (1). In addition, recent studies show that CCR5 cell-surface density correlates with disease progression in infected individuals (2).

The natural ligands of CCR5 [the β-chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES] inhibit entry of R5 strains of HIV-1 in both lymphocytes and macrophages (3). The inhibitory effect of β-chemokines is proposed to act through blocking of CCR5 as well as through down-regulation of the coreceptor from the cell surface. Inhibition of viral entry has also been achieved by blocking the binding of the viral gp120 to the CCR5 coreceptor by antagonist molecules such as TAK-779 (4) or SCH-C (5).

In the present study, we describe another approach toward inhibition of CCR5-mediated viral entry, namely the downregulation of CCR5 protein expression by the immunomodulatory drug rapamycin (RAPA). RAPA, a bacterial macrolide that is currently approved for the treatment of renal transplantation rejection, exerts cytostatic activity in T cells by disrupting molecular events resulting from the binding of IL-2 to the IL-2 receptor (6). We reasoned that RAPA could reduce CCR5 coreceptor expression because CCR5 expression on T cells is strictly dependent on signaling through the IL-2 receptor (7-9). In the present study, we describe the effect of low concentrations of RAPA on CCR5 expression and HIV-1 replication.

Methods

Cell Culture and Flow Cytometry. Cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were performed on normal donors as described (10, 11). PBMCs were maintained in the presence of 100 units/ml rhIL-2 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Cell viability was determined by Trypan blue staining or by the MTT assay (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

RAPA was purchased from Calbiochem. The CCR5 antagonist TAK-779 was obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Rockville, MD).

CCR5 surface expression was measured on PBMCs cultured in the presence of IL-2 for 7-10 days. Staining was done as described (12), but using CCR5 mAb 182 (R & D Systems). Background staining was determined by adding an isotype-matched control (IgG2b, R&DSystems) instead of the anti-CCR5 mAb. Data were acquired by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by using FLOWJO (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Levels of the β-chemokines MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES were measured in culture supernatants by using ELISA kits (R & D Systems).

Infectivity Assays. The following viruses were used in infection experiments: HIV-1 IIIb, HIV-1 ADA, HIV-1 BaL, HIV-1 JRFL, HIV-1 JRCSF, and HIV-1 SF162. HIV-1 IIIb is a T cell line-adapted lab strain that uses CXCR4 for entry into cells, whereas the rest are isolates that use CCR5. Viruses were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

For infection of PBMCs, fresh donor PBMCs were cultured for 7 days in medium containing IL-2. On day 7, cells were exposed to the virus for 3 h. Nonadsorbed virus was removed by washing cells with PBS three times. Infected cells were cultured in IL-2 medium. Infection of MDMs was carried out as described before (11). Unless otherwise indicated, PBMCs were infected by using an moi of 0.001, and MDM were infected by using an moi of 0.002. Virus growth was monitored in culture supernatants by measuring p24 antigen levels by ELISA (NEN) or by measuring viral RT activity in an RT assay (13).

PCR Methodologies. Amplification of CCR5 and β-chemokine RNA sequences was performed by RT-PCR as described (14, 15). In some experiments, the effect of RAPA treatment on virus entry in PBMCs was investigated by DNA PCR. Briefly, PBMCs that had been treated with IL-2 and RAPA for 7 days were infected for 3 h with HIV-1 IIIb or HIV-1 ADA at an moi of 0.05. Virus inocula had been first filtered through a 0.22-μm filter and then treated with DNase (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C to decontaminate the inoculum of HIV-1 DNA. Infected cells were washed extensively to remove residual virus. At 24 h after infection, cell lysates were prepared, and aliquots were amplified by DNA PCR using primer pair M661/M667 (16). Amplified products were detected by liquid hybridization using a 32P-labeled probe (17). Intensities of hybridization signals were measured in a phosphoimager. β-Actin primers were used to control for DNA amount input in the sample.

Results

Effect of RAPA on PBMC Proliferation and Viability. Donor PBMCs were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA (10-fold serial dilutions, from 104 to 0.01 nM). Reduced proliferation, measured by the MTT assay on day 7, was detected at drug concentrations ≥1 nM (Fig. 1). Drug toxicity was observed at drug concentrations above 103 nM (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of RAPA on proliferation of PBMCs. Purified PBMCs from normal donors were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA. On day 7, the extent of cell proliferation was measured by the MTT assay. Representative results obtained on one of two independent experiments, each using cells from four donors, are shown. For each donor, data values are mean ± SD of three independent wells.

RAPA Down-Regulates CCR5 Expression on T Lymphocytes and Monocytes. We first determined the specificity of the CCR5 surface-staining protocol by measuring CCR5 expression on lymphocytes from a normal donor and from a donor previously characterized as homozygous for the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene. Before staining, PBMCs from both donors were cultured for 7 days in the presence of IL-2 because these culture conditions up-regulate CCR5 surface expression (8). Results, depicting CCR5 expression on gated CD4 T cells, are shown in Fig. 2a. They indicate that the methodology used can specifically detect CCR5 surface expression.

Fig. 2.

RAPA down-regulates CCR5 expression on T cells and monocytes. (a) Staining experiment showing specific detection of CCR5 surface expression on CD4+ T cells from a normal donor, but not on CD4+ T cells from an individual homozygous for the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene. (b) Down-regulation of CCR5 surface expression on CD4+ T cells by RAPA. PBMCs cultured for 7 days in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA were assayed for CCR5 levels. Expression of CCR5 on CD4+ T lymphocytes is shown as a solid line, and fluorescence due to the IgG isotype control is shown as a dashed line. (c) Inhibition of CCR5 mRNA transcription in PBMCs by RAPA. Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs that had been cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA for 7 days (cells from same experiment as on b). Equivalent amounts of RNA were subjected to RT-PCR using primer pairs specific for the amplification of CCR5 mRNA (Upper) and 18S ribosomal RNA (Lower). (d) RAPA down-regulates CCR5 cell-surface expression on maturing monocytes. Monocytes cultured for 5 days in the presence of RPMI 20/10% ABHS and RAPA were dually immunostained for CD14 and CCR5. Changes in CCR5 surface expression were examined in CD14-gated cells. The immunofluorescence profile obtained with the anti-CCR5 mAb 182 (solid line) is compared with that of the IgG2b isotype control (dashed line). Results in b and c are representative of data obtained in PBMCs from five different donors. Results in d are representative of similar profiles obtained on three different donors.

To determine the effect of RAPA on CCR5 surface expression on lymphocytes from normal donors, fresh donor PBMCs were cultured in IL-2 medium in the presence of increasing concentrations of RAPA (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 nM) for 10 days. On days 7 and 10, CCR5 surface expression on CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes was measured by dual staining with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies in combination with anti-CCR5 mAb 182 and analysis on the FACS. Day 7 and 10 results indicated that RAPA concentrations ≥1 nM down-regulated CCR5 surface expression on CD4 lymphocytes in the five donors tested. RAPA at 0.1 nM down-regulated CCR5 protein expression on CD4 lymphocytes from some but not all donors. Representative day 7 results, showing concentrations of RAPA that effectively down-regulated CCR5 in all donors, are depicted on Fig. 2b. A similar decrease on CCR5 expression was evident on the CD8 lymphocyte subset, and CCR5 down-regulation in both CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte subsets was also observed on day 10 (data not shown).

At the transcription level, semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from RAPA-treated PBMC cultures showed decreased amounts of CCR5 transcripts in the presence of drug (Fig. 2c Upper). RT-PCR analysis of ribosomal 18S RNA indicated similar RNA content among samples yielding reduced levels of CCR5 transcripts (Fig. 2c Lower). In addition, amplification of RNA samples in the absence of the RT step gave no amplification signal, thus ruling out the possibility of cellular DNA contamination in the RNA preparations (data not shown).

Similarly, monocytes cultured for 5 days in the presence of RAPA showed reduced levels of CCR5 surface expression as compared with the drug-untreated cultures (Fig. 2d). Experiments using monocytes from three different donors showed consistent down-regulation of CCR5 surface expression at RAPA concentrations as low as 0.01 nM. Representative results obtained after CCR5 staining of monocytes from one of the donors are shown.

These results show that RAPA reduces CCR5 surface expression on cultured T lymphocytes (both CD4 and CD8) and monocytes. Together with the RT-PCR results in PBMCs, these results suggest that RAPA interferes with CCR5 expression by reducing gene transcription.

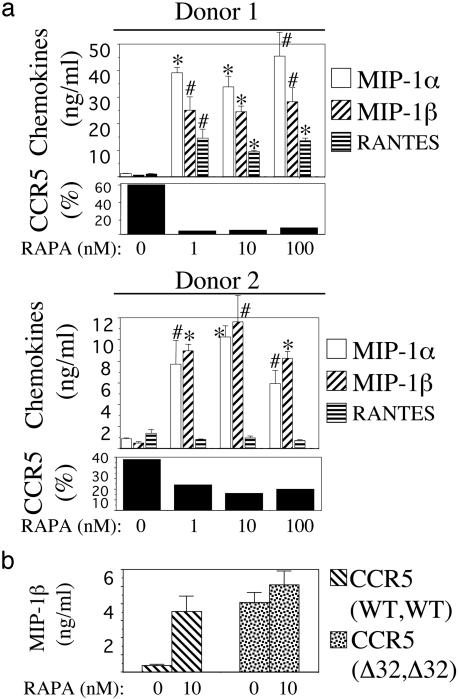

RAPA Increases Extracellular Levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β in PBMC Cultures. Because lymphocytes and monocytes cultured in the presence of RAPA presented reduced CCR5 RNA and protein levels, we next measured levels of the CCR5 ligands MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES in supernatants of RAPA-treated PBMC cultures. PBMCs from four donors were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA for 10 days. On day 10, percentage of cells expressing CCR5 and supernatant chemokine content were determined for each donor. As in previous experiments, RAPA treatment resulted in reduced levels of CCR5 protein expression. When chemokine content in culture supernatants was measured, it was found that MIP-1α and MIP-1β levels were higher in the presence of RAPA than in its absence in all four donors. Among the different donors, RAPA-treated cultures contained 6-39-fold higher levels of MIP-1α than untreated cultures. Similarly, MIP-1β levels were increased 17-47-fold in the presence of RAPA as compared with untreated controls. In contrast, levels of RANTES in the presence of RAPA were increased in two donors while remaining unchanged or even decreasing in the others. Chemokine results obtained in two of the donors, showing disparity of RANTES levels in the presence of RAPA, are depicted in Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3.

RAPA increases extracellular β-chemokine levels in PBMC cultures. (a) Donor PBMCs were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RAPA for 10 days, at which time supernatants were evaluated for β-chemokine content by ELISA and cells were stained for CCR5 expression. Percentage of CD4 lymphocytes expressing CCR5 at each concentration of RAPA is indicated. Results shown in two donors are representative of four experiments using four different donors. *, P < 0.01; #, P < 0.05, compared with untreated control by Student's t test. (b) Effect of RAPA on extracellular levels of MIP-1β in cultures of CCR5-null PBMCs. Levels of MIP-1β protein in the presence and absence of RAPA were measured in supernatants of IL-2-stimulated PBMCs from a normal donor and from a donor homozygous for the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene. Values were obtained on day 10 of culture and are means ± SD of duplicate wells. Results are representative of two independent experiments, each using cells from two normal donors.

To determine whether the increased levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β proteins detected in the supernatants of RAPA-treated cells were the result of increased transcriptional activity, total RNA from RAPA-treated and untreated cultures was amplified by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Amplification of RNA isolated in days 3, 7, and 10 of culture with primer pairs specific for MIP-1α and MIP-1β showed no differences in transcript amount for either chemokine between RAPA-treated and untreated cultures (data not shown). These data suggested that RAPA does not augment extracellular MIP-1α/β levels by enhancing the production of chemokine transcripts.

The above results, showing that RAPA treatment of cells resulted in reduced amounts of CCR5 transcripts (and protein levels) without enhancing the production of chemokine transcripts, suggested that the observed increases on MIP-1α/β proteins could be due to a lack of chemokine uptake on RAPA-treated cells. We addressed this question by evaluating the effect of RAPA on the secretion of MIP-1β, a chemokine that uses CCR5 as its only receptor, in cultures of PBMCs derived from a donor homozygous for the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene. In this experimental setting, in which MIP-1β cannot be endocytosed by CCR5, the effect of RAPA on MIP-1β protein levels should provide information regarding the mechanism by which RAPA increases β-chemokine levels. To this end, stimulated PBMCs from two normal donors and from a CCR5-null donor were cultured in the presence of RAPA as in previous experiments. MIP-1β levels in supernatants were evaluated on day 10. Representative results obtained in one of the normal donors are shown next to the results obtained on the CCR5-null donor (Fig. 3b). In the normal donor, RAPA treatment resulted in an increased level of MIP-1β protein (9.3-fold increase as compared with the RAPA-untreated control) as expected from previous experiments. However, MIP-1β levels in the CCR5-null donor were only increased by 1.2-fold in the presence of RAPA. Together, these results suggest that increased levels of MIP-1β protein, and probably MIP-1α, in the presence of RAPA likely reflect chemokine accumulation due to diminished uptake by cells presenting reduced levels of CCR5 coreceptor.

Antiviral Activity of RAPA in PBMCs. The antiviral activity of RAPA was assayed in PBMCs that had been cultured in the presence of RAPA for 7 days before infection. Cells were infected with the X4 HIV-1 IIIb and the R5 HIV-1 ADA strains. Infected cells were cultured in the presence of RAPA (same concentration as during pretreatment) for 7 additional days, during which time virus replication and cell viability were measured. In a total of seven different experiments using cells from different donors, the antiviral effect of RAPA was more potent against HIV-1 ADA than against HIV-1 IIIb. At 10 nM RAPA, the average value of HIV-1 ADA inhibition in the seven experiments was 91% (range of 88-97%), whereas at 100 nM RAPA, HIV-1 ADA was inhibited by 94% (range of 92-99%). In contrast, 10 nM RAPA inhibited HIV-1 IIIb by 13.5% (range of 5-25%), and 100 nM RAPA inhibited HIV-1 IIIb by 32% (range 29-60%). Results obtained in one of the donors are shown in Fig. 4a.

Fig. 4.

RAPA inhibits HIV-1 replication in PBMCs, and the antiviral activity in R5 HIV-1 is greater than in X4 HIV-1. (a) Seven-day RAPA-treated PBMCs were infected with HIV-1 IIIb or HIV-1 ADA. Infected cells were cultured in the presence of drug for 7 days, at which time virus replication was measured by p24 and cell viability was measured by the MTT assay. Results (means ± SD of triplicate wells) are representative of seven independent experiments, each on cells from a different donor. (b) DNase-treated stocks of HIV-1 IIIb and HIV-1 ADA were used to infect PBMCs that had been treated with or without 100 nM RAPA. HIV-1 DNA sequences were amplified by PCR in cellular lysates prepared 24 h after infection. Amplified PCR products were detected with a radioactive probe. + indicates presence of RAPA in the PBMC culture before and after infection; - indicates no RAPA treatment. Amplification of β-actin sequences indicated same amount of cellular DNA among the different cell lysates (data not shown). NC denotes PCR negative control. (c) The antiviral activity of low concentrations of RAPA was investigated in a panel of R5 strains of HIV-1. Cell proliferation was assayed on uninfected cells from same donor cultured under identical conditions. Results (means ± SD of triplicate wells) are representative of three independent experiments, each on different donor cells.

To further demonstrate the disproportionate antiviral effect of RAPA on R5 versus X4 HIV-1 strains, the antiviral effect of the drug was next assessed by measuring viral DNA in cells shortly after infection. Donor PBMCs that had been cultured for 1 week in the presence (100 nM RAPA) or absence of drug were infected with DNase-treated stocks of R5 HIV-1 ADA or X4 HIV-1 IIIb. At 24 h after infection, cell lysates were prepared and amplified for HIV-1 DNA sequences by PCR. Amplified PCR products were detected by using a radiolabeled probe (Fig. 4b). Phosphoimager analyses of the radioactive signals indicated that HIV-1 IIIb DNA content was the same in the RAPA-treated and untreated cells. In contrast, HIV-1 ADA DNA content in the RAPA-treated cells was three times lower than in the untreated cells. Primer pairs specific for the β-actin gene indicated the same DNA input among samples (data not shown).

As the results obtained with HIV-1 IIIb and HIV-1 ADA suggested that RAPA exerted a more potent antiviral effect in R5 than in X4 HIV-1, the antiviral activities of low concentrations of RAPA (0.01, 0.1, and 1 nM) were next evaluated against a panel of five R5 strains of HIV-1 (Fig. 4c). At these concentrations of RAPA, antiviral activity was seen against R5 strains but not against HIV-1 IIIb. RAPA at 0.01 nM inhibited R5 HIV-1 by 10-64% depending on the strains, whereas 0.1 nM RAPA inhibited virus replication by 15-85%. At 1 nM RAPA, all R5 viruses were inhibited by ≥90%. Together, these results demonstrate that RAPA decreases the susceptibility of PBMCs to be infected by CCR5-using strains of HIV-1 while having little effect in CXCR4-using strains.

Antiviral Activity of RAPA in Macrophages. The antiviral activity of RAPA in MDMs was first assayed under the culture conditions shown to down-regulate expression of CCR5 (see above results). To this end, donor monocytes were cultured for 5 days in the presence of RAPA. On day 5, cells were infected with HIV-1 ADA. Infected cells were cultured in the presence of RAPA for an additional 14 days. Virus production was measured on the culture supernatants on days 7, 10, and 14 after infection. Cell viability was measured by the MTT assay at the end of the experiment (Fig. 5). Over the course of the experiment, RAPA inhibited virus replication in a dose-dependent manner. On day 14, RAPA concentrations ranging 0.1-100 nM inhibited virus production by 70-95%. Cell viability at the end of experiment was reduced at RAPA concentrations ≥10 nM. In an additional experiment in which RAPA was used at 0.01 nM, the R5 viruses HIV-1 ADA and HIV-1 SF 162 were inhibited by 64% and 45%, respectively (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

RAPA inhibits HIV-1 replication in MDMs. Purified monocytes were cultured for 5 days in the presence of RAPA. On day 5, cells were infected with HIV-1 ADA and cultured in the presence of RAPA for 14 additional days. On days 7, 10, and 14 after infection, virus growth was measured by the RT assay. On day 14, cell viability was determined by MTT. Results (means ± SD) are representative of data obtained in three independent experiments, each using cells from a different donor.

In the above-described experiment, monocytes had been pretreated with RAPA during the 5-day differentiation period. To control for the possible interference of RAPA with the process of monocyte differentiation, a new infection experiment in which RAPA was not present during the 5-day monocyte differentiation period was designed. To this end, fresh monocytes were cultured for 5 days in the absence of RAPA. On day 5, cells were infected with HIV-1 ADA and then exposed to RAPA. Under these experimental conditions, two independent experiments using monocytes from two different donors indicated that 1 nM RAPA inhibited virus replication by ∼60% in one of the donors and by ∼80% in the other donors (virus production measured on day 14 after infection; data not shown).

Taken together, these results show that RAPA treatment of differentiating monocytes interferes with their ability to become susceptible targets for HIV infection and that RAPA also interferes with the ability of HIV to replicate in already differentiated macrophages.

RAPA Enhances the Antiviral Activity of the CCR5 Antagonist TAK-779. We last tested whether the down-regulation of CCR5 surface expression observed in the presence of RAPA would increase the potency of a CCR5 antagonist drug. To test this hypothesis, donor PBMCs were cultured in IL-2 medium in the absence or presence of RAPA (1, 10, and 100 nM). After 7 days, cells were infected with HIV-1 ADA in the presence of 0.1 nM TAK-779, a concentration of drug showing little antiviral activity. Infected cells were cultured in the presence of RAPA (same concentration as during pretreatment) plus 0.1 nM TAK-779. Virus production was determined 7 days after infection (Fig. 6). In the absence of RAPA, 0.1 nM TAK-779 caused a 21% inhibition of virus replication. However, in the presence of 1 nM RAPA (a concentration of RAPA already exerting a potent antiviral effect), the antiviral effect due to TAK-779 increased from 21% to 74.5% virus inhibition. Similarly, the antiviral activity of TAK-779 was increased to 89% and 96% virus inhibition in the presence of 10 and 100 nM RAPA, respectively. The TAK-779 concentration used did not affect cell viability (data not shown). These results suggest that the antiviral properties of a CCR5 antagonist drug are enhanced by RAPA.

Fig. 6.

RAPA enhances the antiviral activity of the CCR5 antagonist TAK-779. PBMCs that had been cultured in the absence or presence of RAPA (1, 10, and 100 nM) for 7 days were infected with HIV-1 ADA in the presence of 0.1 nM TAK-779. Infected cells were cultured in the presence of RAPA and 0.1 nM TAK-779. On day 7 after infection, virus production was measured by the p24 assay in the culture supernatant. Note the logarithmic scale in the y axis. Data represent means ± SD of triplicate wells. Representative results obtained in one of three independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

In the present work, we have described an approach to inhibit HIV-1 in vitro that may have important implications in the treatment and prevention of HIV-1 infection. This approach involves down-regulation of the viral coreceptor CCR5 by RAPA, a drug approved for use in humans in the setting of solid organ transplantation (18).

We have shown that RAPA inhibits IL-2-mediated up-regulation of CCR5 protein expression on T-lymphocytes, which is known to be mediated by IL-2 receptor signaling (7-9). By flow cytometry analysis, we have demonstrated that such inhibition occurs in both CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocytes at RAPA concentrations ≥1 nM. In addition, RAPA concentrations as low as 0.01 nM resulted in reduced surface expression of CCR5 on maturing monocytes. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis on PBMC RNA revealed that RAPA interfered with the synthesis of CCR5 mRNA transcripts.

Reduced CCR5 expression in the presence of RAPA correlated with increased levels of the β-chemokines MIP-1α and MIP-1β in supernatants of PBMC cultures. By semiquantitative RT-PCR, we demonstrated that the increased levels of MIP-1α/β proteins were not due to increases in chemokine transcripts. These results, coupled with the observation that RAPA increased MIP-1β protein levels in cultures of normal donor PBMCs but not in cultures of CCR5-null donor PBMCs, suggested that the increases in MIP-1β levels observed in the presence of RAPA were probably the result of reduced chemokine internalization by CCR5. It is likely that this explanation may also account for the increased levels of MIP-1α observed in the presence of RAPA. Our observations are similar to studies by Levine et al. (15), which demonstrated that CD28 costimulation of CD4 T cells with beads leads to downregulation of CCR5 mRNA and up-regulation of β-chemokine levels.

The suggested mechanism by which RAPA up-regulates chemokine levels may help explain our earlier work showing increased levels of β-chemokines in the presence of cytostatic agents causing G1 cell-cycle arrest (19). However, it is interesting to note that in the case of RAPA, RANTES levels were not generally increased. Reduced levels of extracellular RANTES in the presence of RAPA might have been due to uptake of this chemokine by any of the other chemokine receptors to which RANTES binds in addition to CCR5 (20). Moreover, reduced levels of extracellular RANTES could be due to transcriptional mechanisms. In fact, RANTES belongs to the family of genes that turn on late in response to cellular activation. In contrast, both MIP-1α and MIP-1β are the products of genes being turned on early after cellular activation (21).

After having demonstrated that RAPA down-regulates the expression of the CCR5 coreceptor in both T cells and macrophages, we assessed the potential role of RAPA on the inhibition of HIV-1 replication. We performed the antiviral assays on cells that had been cultured under conditions previously reported as up-regulating expression of CCR5, i.e., culture of PBMCs for 7-14 days in the presence of IL-2 (7, 8). These culture conditions have been described as being more physiologically relevant to the in vivo process of cell infection than protocols using mitogen-activated cells (22, 23). Thus, PBMCs were infected after having been cultured for 7 days in IL-2 medium supplemented with various concentrations of RAPA. We first investigated the effect of RAPA on the CCR5 and CXCR4-mediated replication of the virus on PBMCs. Results from these experiments indicated that RAPA exerted a disproportionately greater antiviral effect on the prototype R5-using virus HIV-1 ADA than in the X4-using virus HIV-1 IIIb. The differential antiviral activity of RAPA on R5- and X4-viral strains on PBMCs was further demonstrated by PCR amplification of viral sequences on cell lysates prepared 24 h after infection. Indeed, the PCR results demonstrated that infection by an R5 virus, but not by an X4 virus, is adversely affected on RAPA-treated cells.

Evaluation of the antiviral activity of RAPA on macrophages indicated that 0.01 nM RAPA was sufficient to potently abrogate virus production by this cell type. RAPA was effective on suppressing viral replication when added to maturing monocytes or when added to differentiated macrophages.

We next evaluated the antiviral activity of RAPA in PBMCs on a panel of viruses known to use CCR5 as viral coreceptor. The results indicated that low concentrations of RAPA (0.01-1 nM) had antiviral effect against R5 HIV-1 but not against HIV-1 IIIb. These results, in which total PBMCs were used as viral targets, further support the concept of RAPA inhibiting virus replication by down-regulating coreceptor expression. At RAPA concentrations of 0.01 and 0.1 nM, modest inhibition of virus replication was observed, which is consistent with the FACS analysis data demonstrating CCR5 down-regulation on macrophages, but not on T cells, at the lowest concentrations of drug. However, RAPA concentrations ≥1 nM, which result in CCR5 down-regulation on both T cells and macrophages, potently inhibited virus replication.

Finally, RAPA is shown to enhance the antiviral activity of a CCR5 antagonist molecule. It is reasonable to think that decreased surface expression of CCR5 might result in increased potency of low concentrations of a CCR5 antagonist. Indeed, our results indicate that low concentrations of the antagonist TAK-779 exert a more potent antiviral effect when added in the presence of RAPA.

Taken together, these results suggest that the effects of RAPA on CCR5 expression and extracellular β-chemokine levels could help protect lymphocytes and macrophages against HIV-1 infection. Moreover, a recent report by Roy et al. (24) has shown that RAPA inhibits LTR-mediated transcription of HIV-1. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that RAPA could have important clinical application in the treatment and prevention of HIV-1 infection. RAPA is currently approved for the prophylactic treatment of kidney rejection (18), and recent clinical trials support the use of the drug in the treatment of coronary restinosis (25). The basis for these uses of the drug lies on its potent antiproliferative activity in cells. Although it may not seem appropriate to suggest the use of an immunosuppressant in HIV-infected individuals, it is important to point out that RAPA exerts a potent in vitro antiviral activity at concentrations lower than the ones used to cause immunosuppression in patients. In renal transplant recipients, a daily administration of 2 and 5 mg of RAPA results in therapeutic through levels of 9.3 ± 4.4 nM and 18.9 ± 8 nM, respectively [Rapamune package insert (2002), Wyeth]. In our studies, 0.01 and 0.1 nM RAPA inhibited the replication of some R5 strains of HIV-1 in PBMCs without affecting cell proliferation. RAPA concentrations of 1 nM had mild antiproliferative effects on cells and profoundly suppressed the replication of all R5 strains tested.

The targeting by RAPA of a cellular component such as CCR5, as opposed to targeting of the virus itself, offers an antiviral strategy that is less likely to lead to virus resistance, as cellular components are not expected to mutate under drug pressure. This strategy was initially demonstrated with hydroxyurea (26) and more recently with agents that directly target CCR5 (27). It is conceivable that under the presence of RAPA, HIV-1 may evolve to use CXCR4 as alternative coreceptor. However, in vitro evidence using a CCR5 antagonist suggests that resistance to the antagonist results from a more efficient use of CCR5 by the virus and not from a switch on coreceptor use (28). The fact that CCR5 antagonist-resistant HIV-1 depends on CCR5 coreceptor for infection suggests that down-modulation of CCR5 by RAPA will interfere with the growth and emergence of such variants.

Our in vitro studies suggest that RAPA would be more effective in controlling the replication of R5 than X4 strains of HIV-1. In this regard, the therapeutic use of RAPA as a treatment of early HIV-1 disease (before appearance of X4 strains) may prove of value, particularly in light of current guidelines that advocate delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy (29). Furthermore, the antiviral properties of RAPA could be especially relevant in geographical areas where subtype C HIV-1 is present, as these viruses use CCR5 as major coreceptor (30). Subtype C HIV-1 infections have risen in prevalence over the last decade, and they currently constitute the predominant subtype worldwide (31).

Moreover, the antiviral properties of RAPA could provide new treatment opportunities for suppression of allograft rejection in HIV-infected subjects undergoing solid organ transplantation. Use of the calcineurin inhibitor CsA in this clinical setting has provided conflicting results with regard to both drug toxicity and virus control (32-34). The antiviral properties of RAPA, coupled with its antiangiogenic properties (35), suggest that RAPA might offer a better choice for HIV patients undergoing organ transplantation.

In summary, the ability of RAPA to down-regulate CCR5 coreceptor expression and to augment extracellular levels of β-chemokines offers a new strategy with important implications for the treatment and prevention of HIV-1 infection. The combination of RAPA and CCR5 antagonists may prove especially effective in controlling virus replication in patients. Clinical evaluation to determine the in vivo utility of these provocative in vitro findings is warranted, and clinical protocols (both in infected and uninfected individuals) are now in progress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nelson Michael for providing cells from a Δ32-CCR5 homozygous donor, Tony DeVico and David Pauza for helpful suggestions on the design of experiments, Oxana Barabitskaya for sharing PCR methodologies, and Julie Strizki for technical advice on CCR5 staining. We also thank the Institute of Human Virology Quant Facility for performance of ELISA.

Abbreviations: RAPA, rapamycin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; MDM, monocyte-derived macrophage.

References

- 1.Liu, R., Paxton, W., Choe, S., Ceradini, D., Martin, S., Horuk, R., MacDonald, M., Stuhlmann, H., Koup, R. & Landau, N. (1996) Cell 86, 367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin, Y.-L., Mettling, C., Portales, P., Reynes, J., Clot, J. & Corbeau, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15590-15595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocchi, F., DeVico, A., Garzino-Demo, A., Arya, S., Gallo, R. & Lusso, P. (1995) Science 270, 1811-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba, M., Nishimura, O., Kanzaki, N., Okamoto, M., Sawada, H., Iizawa, Y., Shiraishi, M., Aramaki, Y., Okonogi, K., Ogawa, Y., et al. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strizki, J., Xu, S., Wagner, N., Wojcik, L., Liu, J., Hou, Y., Endres, M., Palani, A., Shapiro, S., Clader, J. W., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12718-12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sehgal, S.-N. (1998) Clin. Biochem. 31, 335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loetscher, P., Seitz, M., Baggiolini, M. & Moser, B. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 184, 569-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleul, C., Wu, L., Hoxie, J., Springer, T. & Mackay, C. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1925-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman, D., Dybul, M., Daucher, M., Davey, R., Walker, R. & Kovacs, J. (2000) J. Infect. Dis. 181, 933-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poli, G. & Fauci, A. (1993) in Current Protocols in Immunology, eds. Coligan, J. E., Kruisbeek, A. M., Margulies, D. H., Shevach, E. M. & Strober, W. (Wiley, New York), pp. 12.3.1-12.3.7.

- 11.Perno, C. & Yarchoan, R. (1993) in Current Protocols in Immunology, eds. Coligan, J. E., Kruisbeek, A. M., Margulies, D. H., Shevach, E. M. & Strober, W. (Wiley, New York), pp. 12.4.1-12.4.11.

- 12.Lane, B., Markovitz, D., Woodford, N., Rochford, R., Strieter, R. & Coffey, M. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 3653-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willey, R., Smith, D., Lasky, L., Theodore, T., Earl, P., Moss, B., Capon, D. & Martin, M. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baba, M., Imai, T., Yoshida, T. & Yoshie, O. (1996) Int. J. Cancer 66, 124-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine, B., Mosca, J., Riley, J., Carroll, R. G., Vahey, M. T., Jagodzinski, L. L., Wagner, K. F., Mayers, D. L., Burke, D. S., Weislow, O. S., et al. (1996) Science 272, 1939-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zack, J., Arrigo, S., Weitsman, S., Go, A., Haislip, A. & Chen, I. (1990) Cell 61, 213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spina, C., Guatelli, J. & Richman, D. (1995) J. Virol. 69, 2977-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahan, B. & Camardo, J. (2001) Transplantation 72, 1181-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heredia, A., Davis, C., Amoroso, A., Dominique, J., Le, N., Klingebiel, E., Reardon, E., Zella, D. & Redfield, R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4179-4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward, S., Bacon, K. & Westick, J. (1998) Immunity 9, 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ullman, K., Northrop, J., Verweij, C. & Crabtree, G. (1990) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8, 421-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinter, A., Poli, G., Fox, L., Hardy, E. & Fauci, A. (1995) J. Immunol. 154, 2448-2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zella, D., Riva, A., Weichold, F., Reitz, M. & Gerna, G. (1998) Immunol. Lett. 62, 45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy, J., Sèbastien, J., Fortin, J. & Tremblay, M. (2002) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 3447-3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poon, M., Badimon, J. & Fuster, V. (2002) Lancet 359, 619-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lori, F., Malykh, A., Cara, A., Sun, D., Weinstein, J. N., Lisziewicz, J. & Gallo, R. C. (1994) Science 266, 801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmons, G., Clapham, P., Picard, L., Offord, R. E., Rosenkilde, M. M., Schwartz, T. W., Buser, R., Wells, T. N. & Proudfoot, A. E. (1997) Science 276, 276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trkola, A., Kuhmann, S., Strizki, J., Maxwell, E., Ketas, T., Morgan, T., Pugach, P., Xu, S., Wojcik, L., Tagat, J., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 395-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dybul, M., Fauci, A., Barlett, J., Kaplan, J. & Pau, A. (2002) Ann. Intern. Med. 137, 381-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjornal, A., Sonnerborg, A., Tscherning, C., Albert, J. & Fenyo, E. (1999) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15, 647-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Essex, M. (1999) Adv. Virus Res. 53, 71-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrieu, J., Even, P. & Tourani, J. (1998) in Autoimmune Aspects of HIV Infection, eds. Andrieu, J.-M., Bach, J.-F. & Even, P. (R. Soc. Med. Services, London), pp. 191-194.

- 33.Rizzardi, G., Harari, A., Capiluppi, B., Tambussi, G., Ellefsen, K., Ciuffreda, D., Champagne, P., Bart, P., Chave, J., Lazzarin, A. & Pantaleo, G. (2002) Clin. Invest. 109, 681-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calabrese, L., Lederman, M., Spritzler, J., Coombs, R., Fox, L., Schock, B., Yen-Lieberman, B., Johnson, R., Mildvan, D. & Parekh, N. (2002) J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 29, 356-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guba, M., von Breitenbuch, P., Steinbauer, M., Koehl, G., Flegel, S., Hornung, M., Bruns, C. J., Zuelke, C., Farkas, S., Anthuber, M., et al. (2002) Nat. Med. 8, 128-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]